ABSTRACT

Integrated reporting (IR) is a new communication tool that is gaining increasing attention among scholars, practitioners, and standard setters in both the private and public sectors. Therefore, it is important to discuss the suitability of the framework proposed by the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC). This paper offers some reflections based on case studies of public entities that differ in terms of legal structures, locations, and business models to demonstrate—despite legal and cultural requirements—that some common features exist. The primary aim is to discuss whether IR represents a new challenge for public sector organisations, specifically regarding their stakeholder engagement and their pursuit of greater accountability. In doing so, the selected case studies are examined through a theoretical framework based on the growing IR literature and specific objectives recognised by the <IR> Framework. The results that emerge from this study can be beneficial for both scholars and practitioners, enabling the identification of new paths towards improving reporting in public entities to achieve high stakeholder engagement and overcome the possible limitations of the IR model that has been proposed thus far.

Key words: Integrated reporting, integrated reporting framework, stakeholder engagement, public sector entities, accountability, state-owned enterprises.

New trends in non-financial disclosure: An introduction

The present research aims to discuss whether and how public sector entities can employ integrated reporting (IR) as a suitable tool to provide information related to financial, environmental, and social performance, as well as governance issues, in one document. The research is motivated by the profound changes that corporate reporting has undergone in both the private and public sectors in response to several types of pressure. Stakeholders require more information-not only related to financial performance but extended to environmental, governance, and sustainability issues as well (Gray, 2006; Dumay et al., 2010; Milne and Gray 2013). Policymakers, standard setters, legislators, and scholars have been paying increasing attention to different information needs with a view to overcoming the limitations that are commonly raised regarding annual reports. In the public sector, the traditional financial report has been blamed for the limited attention paid to the future of public sector entities; this is because it focuses primarily on the financial aspect (Guthrie et al., 1999). The ability of financial reporting to meet citizens’ information needs has been questioned because accounting information is technical in nature and difficult to understand (Brusca and Montesinos, 2006). In addition, the information overload that may occur under the growing pressure for transparency may lead to reduced attention from and lower engagement by stakeholders (Curtin and Meijer, 2006). Undoubtedly, governments have an increasing tendency to enhance transparency and emphasise financial reporting to engage with their stakeholders (Mack and Ryan, 2007), in line with a New Public Governance (NPG) approach to managing public entities (Osborne, 2010). Based on this perspective, information and communication technologies (ICT) have facilitated communication with citizens, and governments have put forth considerable efforts to enhance online disclosure and democratic participation by citizens as a way to gain legitimacy (Brusca et al., 2016).

For these reasons, researchers are proposing the use of tools to increase the production of information that is accessible, as well as easy to obtain and understand, as the so-called ‘popular report’ (Cohen and Karatzimas, 2015; Cohen et al., 2017). With the development of a different strand of research touching upon the theoretical and practical consequences of adopting IR, the need has been identified for empirical research investigating case studies (De Villiers et al., 2014, 2017; Dumay et al., 2017). The present research adopts a case study method to assess whether IR may be a suitable tool for public sector entities. Public sector entities have been selected among those publishing reports that include environmental, governance, sustainability, and financial information. The aim is to determine whether the changes occurring in reporting tools are consistent with the information needs of stakeholders in the public domain, beyond specific cultural and legal requirements that characterise different context. The selected case studies are examined through a theoretical lens that is based on the <IR> Framework issued in 2013 and the recent and relevant literature on the matter. The results of this study may provide a stimulus for practitioners and standard setters to develop detailed and specific guidelines for public sector entities that encompass these organisations’ distinct features. Moreover, this study may contribute to the growing strand of research on IR in the public sector (Guthrie et al.,2017; Katsikas et al., 2017).

The development of integrated reporting

The common call for a report that concisely and effectively provides information on an organisation’s social, economic, and financial impacts is all but new. Since 1953, when Howard Rothmann Bowen published his article ‘Social Responsibilities of the Businessman’, attention towards a more sustainable method of creating value has increased substantially. The concept of a different, holistic form of disclosure that is suitable for comprehending financial and non-financial information in a forward-looking perspective animated the theoretical debate for many years, and scholars have promoted the preparation of reports suitable to demonstrate corporate sustainability (Ball and Grubnic, 2007; Elkington, 1999; Gray, 2006; Guthrie et al., 1999 and Milne and Gray 2013). The increasing possibility of including all financial and non-financial information in one report led to the creation of the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) in 2009. The council was formed by actors with strong regulatory powers related to accounting—the Association of Chartered Certified Accountants, the Chartered Institute of Management Accountants, and the International Federation of Accountants—with the support of the Big Four companies and organisations focused on sustainability reporting, such as the Global Reporting Initiative, the Climate Disclosure Standards Board, and the Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (Dumay et al., 2017). Following a consultation process and a pilot programme that was started in 2011, the IIRC released the Integrated Reporting Framework (<IR> framework) in 2013.

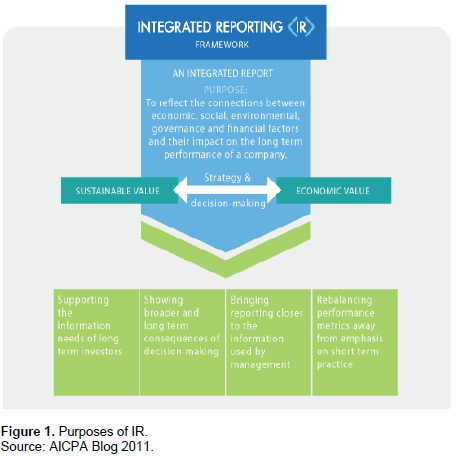

This framework provides guiding principles and content elements to be disclosed in the report that illustrate the thoroughness of the various operations established in accordance with the business model. In addition, and in keeping with a defined vision and mission, the report shows how the inputs (related to the six capitals: financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social and relationship, and natural) have been transformed into outputs and have produced certain outcomes, thereby creating new value. The aim and scope of this new reporting tool are clearly stated in the <IR> Framework: ‘The primary purpose of an integrated report is to explain to providers of financial capital how an organisation creates value over time. An integrated report benefits all stakeholders interested in an organisation’s ability to create value over time, including employees, customers, suppliers, business partners, local communities, legislators, regulators and policy-makers’ (IIRC, 2013). Figure 1 summarises the purpose of the document and highlights how sustainable and economic values should coexist to ensure value creation in the long term. A critical point is the focus on capital providers, rather than on all stakeholders. However, the framework states that all stakeholders may derive advantages from knowing the value created, making clear that <IR> may be undertaken by all kinds of entities: ‘The Framework […] is written primarily in the context of private sector, for-profit companies of any size but it can also be applied, adapted as necessary, by public sector and not-for-profit organizations’ (<IR> Framework).

Standard setters and consulting companies have devoted growing attention to IR and have investigated possible challenges and opportunities (IRC of SA, 2011; ACCA, 2013; EU, 2014; CGMA, 2014; Deloitte, 2015; JSE, 2015; PwC, 2015; GRI, 2015; IIRC, CIPFA, 2016 and Ernest and Young, 2016). Following an initial period wherein scholars were dedicated to exploring IR (Eccles and Krzus, 2010; Eccles and Saltzman, 2011; Jensen and Berg, 2012), some critiques emerged. Some authors discussed whether IR merely represents a new trend in particular areas, such as South Africa (Atkins and Maroun, 2015; Ahmed Haji and Anifowose, 2017; Doni et al., 2016), or if this tool has more to offer (Dragu and Tudor, 2013; Frías-Aceituno et al., 2013), or if the market rewards integrated reporting quality (Cosma et al., 2018). Above all, an intense dialogue involves quite a broad group of scholars discussing how IR can be implemented in organisations and which kinds of changes are necessary so that it does not result in a ‘patchwork’ of different reports. Thus, several researchers have investigated the need for greater effort regarding integrated thinking, which is a prerequisite to enabling IR to paint a holistic picture of the value created by the entity and the contribution of the so-called six capitals, and to analyse stakeholders’ engagement in defining strategies and objectives (de Villiers et al., 2014; Higgins et al., 2014; Guthrie et al., 2017; Katsikas et al., 2017).

Integrated reporting in the public sector: Hurdles, opportunities, and risks

A question that may arise in discussing IR is whether this tool could prove suitable for public sector entities. Scholars have already noted that the use of specific standards or guidelines may represent a way to restore an organisation’s legitimacy (Beck et al., 2017). In looking at the definition offered by the IIRC, IR primarily seems to attract the interest of investors. This may be the case solely for State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs), in which private shareholders may hold a certain number of shares. Moreover, public sector entities are often highly resistant to change, while the fruitful adoption of IR requires managers and politicians to share a common view of strategies and values (Guthrie, 2017). An additional obstacle to implementing IR in public sector entities may relate to their inadequate information technology systems. The preparation of reports requires the collection of accurate data on how entire operations are managed, including results related to the management accounting systems that are in place. As noted by Broadbent and Guthrie (1992), the great diversity of public sector entities means that there are different mechanisms of ownership and control: Some organisations are closer to the market than others, while the role played by elected politicians prevails in other organisations. Thus, accounting tools can play a key role in decision-making, control, and accountability. A holistic document, which incorporates all the different information related to the entity, may increase accountability and transparency. The central focus of IR is the creation of value. In a public entity, this should be interpreted as the creation of ‘public value’, which is inherent in the mission of any public organisation.

An additional perspective to consider is the importance of sustainability in the public sector. According to Birney et al. (2010), ‘public sector organisations are central to the delivery of sustainable development. Every aspect of their role—from education to environmental services, and from planning to social care—shapes how people live their lives’. In the public sector in recent decades, there has been a common tendency to prepare several types of reports (sustainability report, governance report, human rights report, etc.) to meet different information needs. IR may represent an excellent opportunity for public entities that often have a significant impact on the community and environment, as it can provide a holistic view of these different issues and thereby highlight the connectivity that characterises them (Guthrie et al., 2017). However, considering that the <IR> framework was not developed with specific reference to the public sector, the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines may also represent a point of reference for preparing a report that accurately paints a holistic picture of how public entities create value by involving their stakeholders in the decision-making process (Dumay et al., 2017). An additional stimulus, at least in the European context, comes from the European directive on non-financial information. The adoption of IR would undoubtedly facilitate the involved public entities’ compliance with the European directive and the related guidelines (EU, 2014; 2017). It is worth noting that the IIRC has established a Public Sector Pioneer Network to collect experiences and learn by doing (IIRC, 2016). However, this network has not yet proposed specific guidelines or documents to support public entities in their IR preparations.

Benefits related to the adoption of IR by public sector entities have already been posited by scholars and standard setters (IIRC and CIPFA, 2016; Katsikas et al., 2017). First, stronger stakeholder engagement, a pillar of IR that plays a fundamental role in public entities, may enhance democratic participation and increase citizens’ trust. As highlighted by the KPMG report (2012) prepared for the public sector, stakeholder engagement can help an organisation to show how it balances the often-conflicting needs of different stakeholder groups. Second, as noted by Eccles and Krzus (2010), IR ensures greater clarity regarding relationships and commitment, thereby supporting the disclosure of ‘public value creation’ through clear objectives and related metrics and identifying the relationship between these key financial and non-financial metrics. An additional advantage should be an improved decision-making process: Developing a set of metrics to ensure that the strategies, objectives, and activities coincide with the mission and vision of the organisation should improve its ability to approach decision-making holistically. Third, better disclosure improves trust within the entity, and integrated thinking reduces the risk of weak coordination, thus enhancing synergy and favouring the identification of key drivers of public value creation. In this respect, one of the key aims of integrated thinking is to break down silos and spot targets and objectives for the public entity as a whole, as this is meaningful for individuals, divisions, and departments.

Nonetheless, the possible limitations and risks related to the adoption of IR should be considered. One main risk, which is common to the introduction of any new accounting tool (Liguori and Steccolini, 2014), is that the adoption of IR may result in a cosmetic change that has no impact on management routines and actions. Furthermore, to be successful, IR requires managers and politicians to achieve a shared view of its strategies and values, which is anything but easy (Katsikas et al., 2017). Additional limitations and barriers may be detected regarding the application of the <IR> framework to public sector entities: It has not been conceived explicitly for this kind of entity; thus, it does not consider the specific information needed. The lack of indicators is another limitation that is explicitly connected to the <IR> framework, as it creates room for each entity to choose a different standard as a reference to set key performance indicators or to formulate their own indicators. While this choice means there is the possibility to adopt any kind of measures that are more suitable to the specific realm of any single entity, it also reduces comparability between different entities. Bearing this complex scenario in mind, some experiences in different types of public sector entities are analysed in the following sections to identify the extent to which the reports produced by pioneers are consistent with the <IR> Framework or whether a different approach has been undertaken and how this would improve stakeholder engagement.

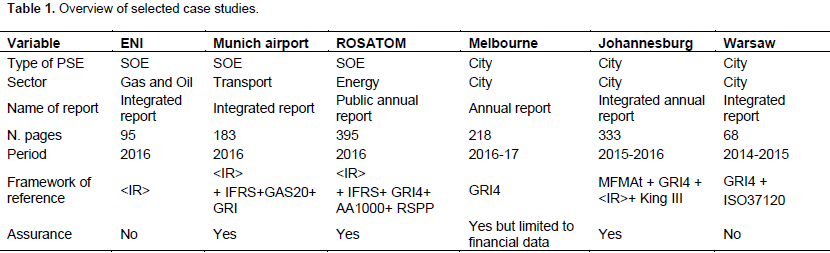

This study discusses whether IR may represent an appropriate tool to improve stakeholders’ engagement in public sector entities. In doing so, a case study approach has been adopted. Case studies are an appropriate research method to employ when ‘a “how” or “why” question is being asked about a contemporary set of events over which the investigator has little or no control’ (Yin, 2014). Case studies have been selected in keeping with the aim of identifying different types of entities in different contexts. Although contextual factors in each continent (for example, different citizens’ awareness of public sector accountability, different cultural approach to dialogue, technological maturity, law requirements) may create incentives for—or, rather, obstacles to—the development of this accountability tool, we believe that comparing experiences done in different contexts may allow for the detection of common features of these new accountability tools (Monfardini, 2010). First, the <IR> database was examined, with ‘public sector’ selected as the type of entity. Based on this criterion, only one report published in 2013 was found (HM Revenue and Customs Annual Report, 2013). However, due to the year of reference and the fact that the report pertained to one year only, it was not considered. Further research was conducted with the aim of examining specific sectors in which SOEs are usually involved. The case of ENI (an Italian listed SOE) was selected on the basis that the report has been prepared annually since 2013.

Based on the same criterion, the research was repeated for the ‘utilities’ and ‘consumer services’ sectors, and the case of Munich Airport and ROSATOM were identified. In keeping with the aim of analysing new reports provided by cities, and considering that none of them was included in the <IR> database, a similar search was run using the GRI database. The cases of the cities of Melbourne and Warsaw were selected to include different regions in the research. Finally, the case of the city of Johannesburg was added to include an example from a country that indubitably represents a benchmark in the field of IR. Using a deductive approach, a theoretical framework was developed and then tested using the appropriate data (Saunders et al., 2009). Following Eccles et al. (2015) and the <IR> framework, four aspects were analysed in the reports: focus of business model, including how many and which capitals have been considered for the value creation process; materiality, to detect what has been considered significant for stakeholders; conciseness, because effective communication requires the satisfaction of information needs in a direct way, and because this requisite is especially important in public sector entities, where the needs to acquire legitimacy and demonstrate value for money imply the ability to provide accessible and clear information (Curtin and Meijer, 2006); and stakeholder engagement, strictly related to the core value of public entities, for which democratic participation and transparency are pillars. The adopted definition is the one provided by Thomson and Bebbington (2005):

Stakeholder engagement describes a range of practices where organisations take a structured approach to consulting with

POTENTIAL stakeholders. There are a number of possible practices which achieve this aim, including: Internet bulletin boards, questionnaire surveys mailed to stakeholders, phone surveys, and community-based and/or open meetings designed to bring stakeholders and organisational representatives together.

Finally, secondary qualitative data from the annual reports, sustainability reports, and official websites of the entities were used to enrich the presentation of the six case studies. Table 1 provides a synthesis of the selected cases.

This section adopts a common approach to analyse the selected cases. Following a short synopsis of each entity, the focus, materiality, and conciseness of the document and the stakeholder engagement as disclosed in the documents are discussed. To enable a certain degree of comparison despite the different locations and types of activity, the three cases related to SOEs and three municipalities are discussed.

ENI

ENI is an Italian SOE that, based on its market value, is the sixth largest integrated energy company in the world. Its primary business is oil and gas, from hydrocarbon exploration to the downstream phase of product marketing. As stated in the section devoted to disclosing its activities, ENI is engaged in increasing the renewable energy sources segment to sustain the path of the business model towards a low-carbon scenario. As an SOE, ENI should disclose its non-commercial objectives, related-party transactions, policy commitments, ownership and governance structures, risk exposure, and risk management. Sustainability is not new to ENI, and it is deeply rooted in its strategies: The first chairman, Enrico Mattei, has managed the company since the 1950s and has built the business on long-term cooperation with producing countries, the transfer of knowledge, and mutual development. ENI prepared its first IR in 2010, abandoning the stand-alone sustainability report and joining the 2011 pilot programme launched by the IIRC. IR 2016 is accessible in both PDF and interactive modality on the web. No assurance is provided on the content or on the process that was followed to prepare the report.

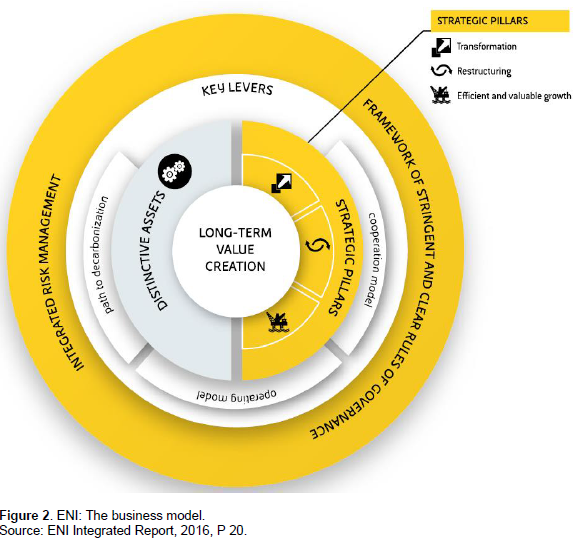

ENI focus

The IR for 2016 provides an in-depth review of the company’s operations and performance, illustrating the business model and the challenges faced during the reporting period. It is worth noting that in defining its strategies, ENI has adopted an integrated thinking approach that reflects its business model. In fact, as declared by the chairman and chief executive officer, ‘The transformation of our model from a divisional organisation to a fully-integrated company, resulted in more streamlined decision making processes and cost savings of €770 million on an annual basis compared to the 2014 budgeted level’ (ENI, 2016). The IR presents the financial results together with information on governance, sustainability, and other material factors identified in accordance with internal and external stakeholders’ needs. The entity’s business model (Figure 2) emphasises the long-term value creation approach, although no reference is made to the six capitals identified by the <IR> Framework rather, it illustrates distinctive assets in relation to the six dimensions of the value creation process. Information on risks is presented in connection with the company’s targets, and forward-looking information is provided in relation to both the short and long terms.

ENI materiality

ENI held an extensive discussion with its stakeholders to determine material issues. The process of identifying, evaluating, and prioritising sustainability issues is based on the strategic plan for the next three years; the risk assessment provided by the internal risk control systems on environmental, sustainability, and governance issues; and the evaluation of the main requests presented by stakeholders, thus integrating internal and external perspectives of what is ‘material’ for the company.

ENI conciseness

The IR prepared by ENI is a good example of conciseness, as all the information is provided in 95 pages. This is the consequence of disclosing essential financial figures: detailed data provided via consolidated reporting. It is worth noting that ENI continues to prepare a sustainability report and a strategic plan, both of which complement the information included in the IR. However, the IR makes limited use of graphs and figures, providing information and presenting strategies in a narrative manner.

ENI stakeholder engagement

In defining its strategies, ENI involves the company’s shareholders, its employees, and the communities in which it operates. It explicitly mentions suppliers, universities and research centres, the financial community, local communities, domestic institutions, European and international institutions, international organisations, national and international NGOs, the United Nations system, customers and consumers, and other sustainability organisations. The activities that involve stakeholders are variegated, ranging from agreements, meetings, conference calls, and workshops to dialogues and discussions with different stakeholders. The focus on stakeholders also emerges in the business model, in which ENI specifies the value created for stakeholders.

Munich airport

Flughafen München GmbH, Munich (FMG), is an SOE. FMG shares are held by the state of Bavaria, the Federal Republic of Germany, and the city of Munich. It started the journey towards IR in 2010, adopting a forward-looking report and becoming a member of the <IR> Business Network. The integrated report is available on the company’s website in the section devoted to ‘responsibility’ and can be consulted online using an interactive approach or downloaded as a PDF. The document includes the audit report related to the consolidated financial statement. The company’s independent assurance report is also available on its website.

Munich airport focus

The report is prepared in accordance with IIRC recommendations but also adheres to German accounting standards and IFRS in relation to financial data. Sustainability targets take into account the GRI comprehensive option. The report describes the business model that has been adopted in relation to long-term strategies, illustrating the main business units through which the value creation process occurs. This involves six capitals (financial, infrastructure, expertise, employees, environment, and society). Considerable attention is paid to future risks and opportunities, and the risk management system is clearly explained. A matrix provides an overview of the risks, illustrating the time frame and the expected financial impact. Similarly, a matrix provides an overview of the opportunities.

Munich airport materiality

Sustainability management, the responsibility of the Corporate Development division, identifies what is considered material for both internal and external stakeholders. The materiality matrix provides readers with a clear map of material issues that are identified by looking at the information needs of internal and external stakeholders in relation to the six capitals. Selected sustainable development goals from the United Nations are also identified in the materiality process (Figure 3).

Munich airport conciseness

The Munich Airport Integrated Report spans 183 pages, of which a high number are dedicated to financial data (82 pages) and sustainability indicators prepared in accordance with the GRI (12 pages). It must be noted that the company also provides an annual report, a consolidated report, and a sustainability programme. However, in the integrated report, the reader can find all the useful information for building a clear vision of the company’s business model and value creation process. Moreover, numerous figures and graphics facilitate the reader’s understanding of the content.

Munich airport stakeholder engagement

Based on the report, the relationship with stakeholders is considered pivotal. Thus, a wide range of communication channels has been activated, including the company’s website and social networking, surveys, meetings, and working groups. The collected opinions are considered while defining business activities.

ROSATOM is a State Atomic Energy corporation based in Russia. Founded in 2007, it is one of the largest power generation companies in Russia and one of the leading players in the use of nuclear energy. It has also developed new businesses that ‘include projects in the sphere of nuclear medicine, wind power, composite materials, additive manufacturing, lasers, robotics, supercomputers, etc’. Performance of State Atomic Energy Corporation ROSATOM in 2016, the public report presented by ROSATOM, is a unique case of a ‘one report’ among the presented cases prepared in accordance with the IIRC Framework, GRI G4, AA1000, IFRS, the Public Reporting Policy of ROSATOM, the Public Reporting Standard of ROSATOM, and RSPP Recommendations for Use in the Governance Practice and Corporate Non-Financial Reporting. ROSATOM’s strategic plan is based on the goal defined by the state and approved by the supervisory board. For this reason, and despite ROSATOM’s strong effort to be transparent and accountable, the limited involvement of stakeholders in the definition of strategies and activities emerges clearly. This effort also results in the public assurance process that is followed. The document is complemented by an independent assurance. In keeping with its holistic nature, the report includes the opinion of the Internal Control and Audit Department in addition to the auditing commission’s report on financial and business operations.

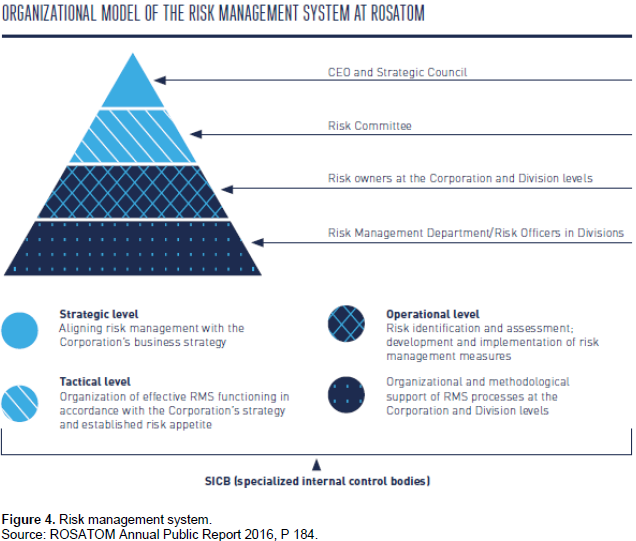

ROSATOM focus

The report presents the business model in a somewhat complex manner that represents the primary business areas and the connection with capitals. Value creation activities are also identified and connected to governing bodies. The six capitals employed in the value creation process are clearly stated and echo those proposed by the IIRC. The risks are identified and connected to strategic goals, thus describing the management approach. The risk management system adopted by ROSATOM is discussed in detail and illustrated in Figure 4. The actions taken to face the perceived risks are also discussed at length in the report, demonstrating the fundamental role of the risk management system. Future plans are examined in relation to the main strategic goals, and details about each strategic unit are provided for the following year.

ROSATOM materiality

The material aspects to be disclosed in the report have been defined in accordance with both GRI G4 and the <IR> framework, thanks to the joint efforts of a working group and top management. Four distinct levels of materiality have been identified, and a stakeholders’ map is provided.

ROSATOM conciseness

The report comprises 395 pages. However, the length is justified by the need to provide detailed accounting information, as it is the only report published by the company. The narrative is complemented by numerous figures, pictures, and graphs to facilitate the reader’s interpretation of the company’s performance.

ROSATOM stakeholder engagements

ROSATOM declares that it involves stakeholders in the decisions made in each area of its business and identifies its main stakeholders. However, upon analysing the information disclosed in the section dedicated to stakeholder engagement, it appears that a strong effort has been made to enhance communication and transparency in accordance with information needs. The stakeholders’ involvement in the decision-making process does not seem clear, which may be due to the nature of the business. However, the report includes a table that discloses the fulfilment of the commitments assumed during its preparation. The individuals involved in the public assurance process related to the 2016 report have also signed the document. In addition, during the year, opinion polls, surveys, dialogues, and public assurance procedures have facilitated communication with stakeholders.

City of Melbourne

Melbourne is the capital of the state of Victoria, Australia, and its annual report for 2016 to 2017 was prepared in accordance with the Local Government Act 1989 and, for all matters related to sustainability, with the GRI4. The report provides information on performance achievement in light of the objectives of the annual plan and budget for the same period, as well as the four-year priorities of the Council Plan 2013 to 2017. The city is home to 148,000 citizens and hosts 743,000 people who visit daily for work and recreation. The report is available on the website in the section devoted to the city council; a feedback form to collect opinions from readers is located on the same page.

City of Melbourne focus

The report is strongly focused on performance achieved against the eight fundamental goals of the four-year plan and in keeping with the vision (provided at the beginning of the report), for which sustainability plays a fundamental role (Figure 5). Neither the business model nor the capitals involved in the value creation process are mentioned, but the planning framework is clearly described in addition to how priorities have been translated into actions. Detailed information about the organisation and its human resources is also provided. Below the index, a disclaimer clarifies that, even if it is accurate, it may not be wholly appropriate for specific purposes. A link is also included for individuals interested in actively participating in the decision-making process.

City of Melbourne materiality

The items included in the report are consistent with those identified in the Local Government Act, but there is no materiality matrix, nor is a clear identification of stakeholders provided. However, consistent with GRI4 requirements, material issues are defined and are presented alongside their related boundaries.

City of Melbourne conciseness

The report is not based explicitly on the principle of conciseness, although it aims to provide a clear picture of the performance in an accessible manner. It consists of 220 pages, including a wide range of service and financial performance indicators and a financial report, which together account for more than a third of the entire report.

City of Melbourne stakeholder engagement

The city of Melbourne devotes considerable effort to involving stakeholders in its decision-making process. For this reason, a section on the website (‘Participate Melbourne’) includes all projects that are open for consultation. Questionnaires, documents, and focus groups are presented to allow for high engagement by all those who are interested in participating in the life of the community, and the report provides some metrics on these activities. In addition, a consultation process involving specific interest groups aims to give a voice to vulnerable stakeholders (Figure 5).

City of Johannesburg

Johannesburg is the biggest city by population size in South Africa, with an estimated population of approximately 4.9 million people. It faces poverty, unemployment, and inequality because many migrants move to the city in search of opportunities for economic prosperity. The report represents the final one related to the Integrated Development Plan 2011/2016, which is a part of Growth and Development Strategy 2040. The city aims to create liveable communities that are closer to basic services and jobs.

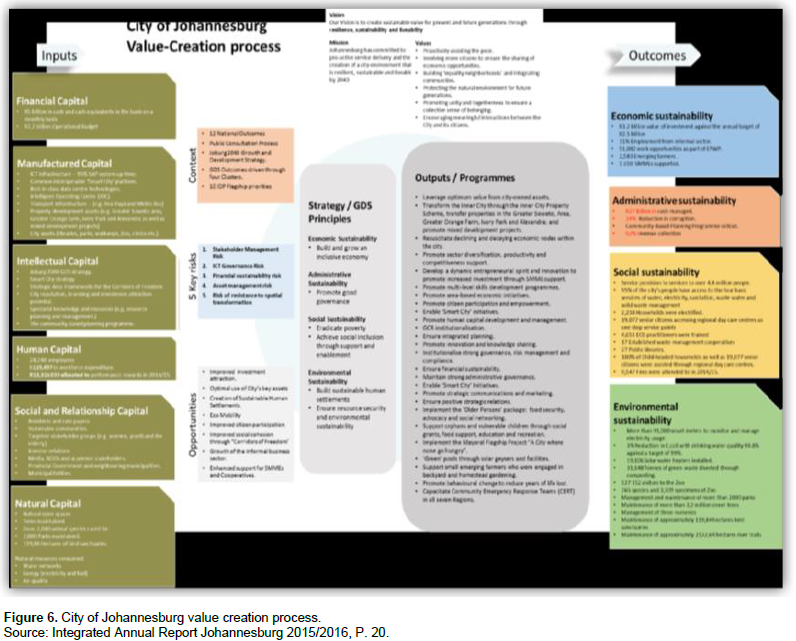

City of Johannesburg focus

Ten strategic priorities are defined and their related programmes disclosed in the report. These are in keeping with the growth and development strategy, and an integrated value creation model is provided to explain how the resources included in the six capitals can be combined in the programmes selected to produce certain outputs and outcomes (Figure 6). More specifically, the outputs are organised into four clusters (sustainable services, economic growth, human and social development, and good governance), while the outcomes are identified in relation to four broad areas: economic, administrative, social, and environmental sustainability.

City of Johannesburg materiality

Material issues are defined in accordance with the growth and development strategy and include key aspects in relation to the four clusters that have already been described. However, the need exists for a proper materiality matrix that can identify material issues in accordance with stakeholders’ needs.

City of Johannesburg conciseness

The report is a consolidated integrated report. Thus, it contains information on SOEs that are under the city’s control. For this reason, it is quite long, consisting of 333 pages. Most of the document (198 of the 333 pages) is dedicated to the disclosure of financial statements and indicators inspired by the GRI4. Because it is mainly narrative in nature, with limited figures, graphs, and pictures, it is not easy to read.

City of Johannesburg stakeholder engagement

The city has embraced a path of engaging with the community, organising regional ward clusters (24 in the period 2015 to 2016) to enable community members, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), councillors, and committees to participate in the preparation of the city’s plans.

City of Warsaw

Warsaw, the capital of Poland, is a city of more than 1.7 million residents. In 2013, it published the first Integrated Sustainability Report. In July 2017, the mayor presented the third report for 2014 to 2015, which is available in English on the website (Warsaw, 2015). Considering that the first report was prepared while the <IR> Framework was still under consultation, it is not surprising that it was prepared in keeping with the GRI4 and indicators of ISO37120. In the subsequent editions, however, the mayor decided to continue with the same model, and introduction explicitly mentions the effort made to ensure comparability with previous reports. The report is available in PDF in both English and Polish. No assurance is provided regarding the content or the methodology followed in preparing the report.

City of Warsaw focus

In accordance with the title, the report discusses the three pillars of sustainability: economic, social, and environmental factors. It offers general information on the governance code and data about employees. It presents facts and data that are essentially framed in the past, with limited reference to future plans and related risks. Because the report was prepared in accordance with the GRI4, there is no specific identification of capital involved

in the value creation process.

City of Warsaw materiality

The report provides the reader with a list of reporting aspects defined in accordance with stakeholders’ requirements. Public consultations using the City of Warsaw’s website and social networks allow for the identification of the reporting aspects included in the document; these are organised into three main areas (economic, social, environmental) and are further structured in specific activities.

City of Warsaw conciseness

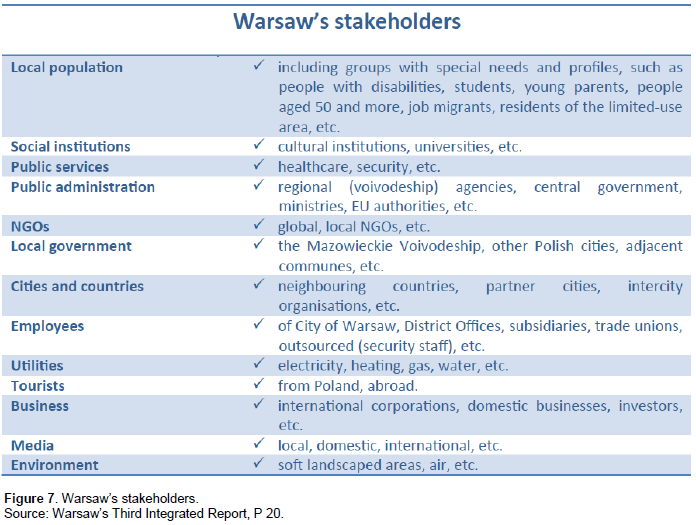

The third report, which devotes considerable effort to conciseness, is 62 pages plus 6 pages of detailed indicators. The data are presented in an easy and understandable format, making extensive use of graphs and pictures that facilitate comprehension. The willingness to facilitate understanding for all stakeholders is evident based on the wide use of graphs, including those that provide a comparative representation of expenditures over the two years (Figure 7).

City of Warsaw stakeholder engagement

The city identifies its core stakeholders as seen in Figure 7. In addition to public consultations, the participatory budget has been adopted, and the plans chosen by citizens have been executed. The report identifies the main stakeholders (the local population, social institutions, public services, public administration, NGOs, local government, cities and counties, employees, utilities, tourists, business, media, and environment) and declares that five different channels have been used to communicate with them: phone, self-service website, mobile app, email, and chat (Figure 7).

New reporting trends in public sector entities

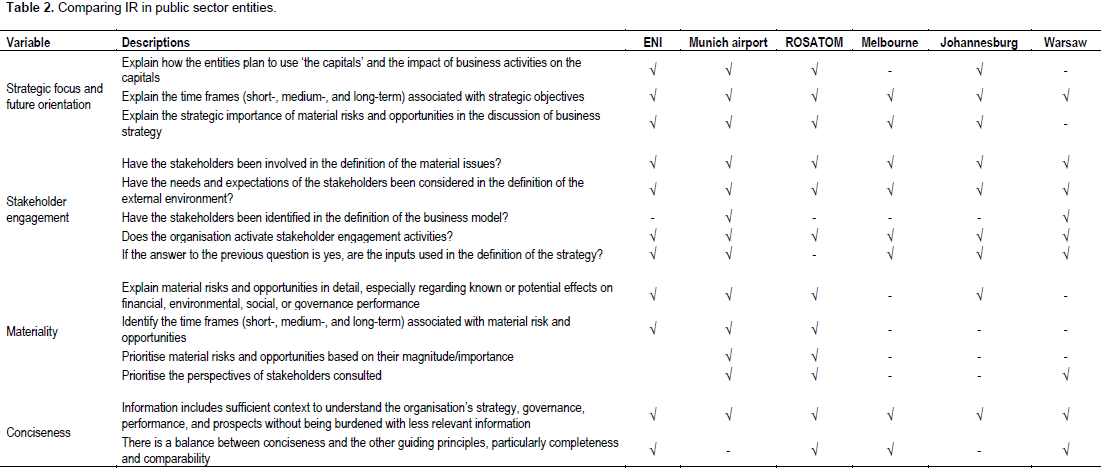

The analysis of these six selected cases deserves further discussion regarding the extent to which the <IR> framework provides a point of reference for preparing a holistic report that is suitable for presenting financial and non-financial information in a language that is accessible to all stakeholders. To this end, Table 2 offers a comparative overview of the cases analysed. A key point to note is that not all entities discussed in the presented cases have decided to follow the <IR> Framework as a point of reference. Of those that have, early adopters (ENI and Munich Airport) have used additional guidelines such as the GRI, a benchmark for sustainability issues and for identifying suitable key performance indicators. The case of Johannesburg begs further deliberation. This report was prepared in accordance with the legal requirements for a municipality in South Africa but also takes into consideration the <IR> Framework and the King III. The level of stakeholder engagement is considerably low, and there is no place for a participatory budget or for defining specific priorities in a clear and transparent manner. Thus, the role played by the environment and by a certain degree of ‘maturity’ on the part of the community regarding its participation in a public entity’s decision-making process may prevail. In the case of Warsaw, even if the document is defined as ‘integrated’, its primary focus is sustainability.

Although some key elements required by the <IR> Framework, including the ‘capitals’, are missing, the report seems suitable for satisfying information needs: The preference for conciseness may lead citizens and other stakeholders to search in other documents when more detailed information is needed. Nonetheless, the report allows stakeholders with no accounting background, such as citizens and taxpayers, to easily understand how resources are used, which resources are prioritised, and the resulting impacts. Undeniably, several differences exist between the cases analysed. However, the comparison is not intended to highlight the differences but to discuss the extent to which the requirements of the <IR> Framework may be well suited to public sector entities and to discern the main common characteristics of the different reports analysed. It is also important to consider whether the reports analysed may represent a tool to enhance stakeholder engagement. Possibly due to their experience as early adopters, ENI and Munich Airport seem to have assumed an integrated thinking approach in defining strategies and facing risks and opportunities, and they have achieved a high level of stakeholder engagement, as shown in their reports (ENI report, pp. 14–15; Munich Airport Report, 2016.p. 26). ROSATOM presents other characteristics that deserve attention. First, due to the type of activities undertaken, strict control is exercised by the central government in defining strategic objectives. Thus, stakeholder engagement can be used only in relation to accountability issues.

This is a clear example of how the public sector’s compelling needs and priorities as defined at the national level may prevail, creating hurdles and barriers to deeper stakeholder engagement in the decision-making process. Again, the business model affects the focus on risks, which is particularly robust and pervades all activities. Nonetheless, the willingness to be accountable has led ROSATOM to provide an assurance process by stakeholders and by an independent auditor. It seems quite clear that IR has been used as a tool to achieve legitimacy in the delicate nuclear energy field, disclosing how much attention and care the company pays to safety and environmental issues. In summary, the case studies presented show the different approaches used by various types of organisations, which is further evidence of IR as a tailor-made tool that must be shaped in accordance with the specific features of each entity and that can be prepared following different frameworks. In this regard, the analysed case studies demonstrate the contemporary use of different references in the preparation of annual reports. The business model can emerge clearly or partially, the risks to be faced can be clarified in connection with different strategies or generally in relation to the whole organisation, and what is material can be identified following an open and continued dialogue or some embryonic forms of consultation with stakeholders.

However, at the core of these reports is the willingness to communicate values, strategies, and actions undertaken, together with output and outcome produced, and to progressively increase stakeholder engagement. It is also clear that the need for accountability may be a major driver in defining material aspects to be disclosed in accordance with requests by different groups of stakeholders, thereby empirically demonstrating the fundamental role of stakeholder engagement in public sector organisations’ sustainability issues (Rinaldi et al., 2014). From this point of view, the integrated report offers public sector entities an excellent opportunity to clarifyhow competing challenges have been balanced to achieve more sustainable growth while respecting intergenerational equity (Ball et al., 2014). It also considers the specific requests of stakeholders, even in those cases in which there is not yet a community that is able to engage in the decision-making process. Moreover, many public sector organisations often must disclose how they comply with national or local strategies defined at the political level, and IR may offer them opportunities to communicate how these overarching objectives have been harmonised with these entities’ missions and values. An additional area that is worth investigating is the integrated thinking approach to defining strategies and actions. One main advantage of an integrated approach is the possibility of breaking down traditional borders between departments or units to achieve a common view of future actions, thus increasing cooperation and coordination (Katsikas et al., 2017). This kind of approach may, in turn, lead to high efficiency in the use of resources, thereby avoiding overlapping and conflicts. However, as already noted by scholars (Higgins et al., 2014), this is possible only if radical changes occur in the entities. The effective adoption of IR requires time and a shared view among managers and, in some public sector entities, politicians (Table 2).

IR is receiving increasing attention from professional organisations, standard setters, and scholars in both the private and public sectors. Early adopters are actively contributing to the improved definition of which content and approach should be followed to ensure the report reflects an innovative way to manage an entity. By analysing six different case studies, this study makes it possible to consider how the approach to IR has been interpreted in different contexts and how stakeholders may be involved in defining material issues. However, it does not investigate internal processes and, consequently, does not allow for an assessment of whether integrated thinking permeates the various organisations. A fundamental lesson emerging from the case studies is that, as it stands, the <IR> Framework does not provide sufficient support for public sector entities for it to be considered the primary reference for accountability purposes. Thus, further effort should be made to interpret the peculiarity of public sector organisations. All reports demonstrate-even if with different nuance—that stakeholder engagement is a key aspect of the accountability process and that in some cases (in particular in the cities) stakeholders have been involved in decision-making processes. IR, then, may be considered a tool to enhance stakeholder engagement, improve accountability, and, in turn, gain legitimacy (Beck et al., 2017; Guthrie et al., 2017).

An additional point that deserves attention is the different levels of ‘maturity’ regarding the approach to IR: In those countries in which NPG is well established and public sector entities are already accustomed to providing information on value for money, illustrating their activities in terms of inputs, outputs, and outcomes, the implementation of IR is a natural development of a disclosure process that is connected to strong stakeholder engagement. Further research on public sector entities would be beneficial, as it would enable a better understanding of how they create public value for the benefit of the community. Standard setters are aware of the relevance of this new tool and are working to provide better support for IR preparation. Working collaboratively with these standard setters, scholars can contribute to discussions about IR content, principles, and practices. Efforts are necessary to avoid the rhetorical use of this tool and unveil all the management changes that are necessary for the implementation of reliable reports that address stakeholders’ information needs.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Association of Chartered Certified Accountants (ACCA) (2013). Understanding investors: directions for corporate reporting, retrieved 11 December 2017

View

|

|

|

|

Ahmed Haji A, Anifowose M (2017). Initial trends in corporate disclosures following the introduction of integrated reporting practice in South Africa. J. Intellect. Cap. 18(2):373-399.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

AICPA Blog (2011) Integrated Reporting Framework in the Profession's Future (posted by Carol Scott), retrieved 11 December 2017 from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Atkins J, Maroun W (2015). Integrated reporting in South Africa in 2012: Perspectives from South African institutional investors. Meditari Account. Res. 23(2):197-221.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ball A, Grubnic S (2007). Sustainability accounting and accountability in the public sector in Unerman, J., Bebbington, J. and O'Dwyer, B. (Eds), Sustainability Accounting and Accountability (Routledge, London).

|

|

|

|

|

Ball A, Grubnic S, Birchall J (2014). Sustainability accounting and accountability in the public sector. in Bebbington. J. Unerman, J., and O'Dwyer, B. (Eds), Sustainability Accounting and Accountability (Routledge, London).

|

|

|

|

|

Beck C, Dumay J, Frost G (2017). In pursuit of a 'single source of truth': from threatened legitimacy to integrated reporting. J. Bus. Eth. 141(1):191-205.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Birney A, Clarkson H, Madden P, Porritt J, Tuxworth B (2010). Stepping Up: A Framework for Public Sector Leadership on Sustainability. Forum for the Future. London: UK.

|

|

|

|

|

Broadbent J, Guthrie J (1992). Changes in the public sector: A review of recent alternative accounting research Accounting, Audit. Account. J. 5(2):3-31.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Brusca I, Manes Rossi F, Aversano N (2016). Online sustainability information in local governments in an austerity context: An empirical analysis in Italy and Spain. Online Inform Rev. 40(4):497-514.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Brusca I, Montesinos V (2006). Are citizens significant users of government financial information?, Pub. Mon. Manag. 26(4):205-209.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chartered Global Management Accountant (CGMA) (2014) Integrated Thinking. The next step in integrated reporting, retrieved 11 December 2017

View

|

|

|

|

|

Cohen S, Karatzimas S (2015). Tracing the future of reporting in the public sector: introducing integrated popular reporting. Int. J. Public Sector Manag. 28(6):449-460.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cohen S, Mamakou XJ, Karatzimas S (2017). IT-enhanced popular reports: Analyzing citizen preferences. Gov. Inf. Q. 34(2):283-295.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cosma S, Soana M G, Venturelli A (2018). Does the market reward integrated report quality? in Afr. J. Bus. Manage. 12(4):78-91.

|

|

|

|

|

Curtin D, Meijer AJ (2006). Does transparency strengthen legitimacy? Inform. Polity, 11(2):109-122.

|

|

|

|

|

de Villiers C, Rinaldi L, Unerman J (2014). Integrated Reporting: Insights, gaps and an agenda for future research. Accounting, Audit. Account. J. 27(7):1042-1067.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

de Villiers C, Hsiao PCK, Maroun W (2017). Developing a conceptual model of influences around integrated reporting, new insights and directions for future research in Meditari Account. Res. 25(4):450-460.

|

|

|

|

|

Deloitte (2015). Integrated Reporting as a driver for Integrated Thinking? retrieved 11 December 2017

View.

|

|

|

|

|

Doni F, Gasperini A, Pavone P (2016). Early adopters of integrated reporting: The case of the mining industry in South Africa. Afr. J. Bus. Manage. 10(9):187-208.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dragu IM, Tiron-Tudor A (2013). The integrated reporting initiative from an institutional perspective: Emergent factors in Procedia. Soc. Behav. Sci. 92:275-279.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dumay J, Guthrie J, Farneti F, (2010). GRI sustainability reporting guidelines for public and third sector organizations: A critical review. Pub. Manag. Rev. 12(4):531-548.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dumay J, Bernardi C, Guthrie J, La Torre M (2017). Barriers to implementing the International Integrated Reporting Framework: A contemporary academic perspective. Meditari Account. Res., 25(4):461-480.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Eccles RG, Krzus MP (2010). One Report. Integrated reporting for a sustainable society. John Wiley & Sons. USA.

|

|

|

|

|

Eccles RG, Krzus MP, Sidney R (2015). The integrated reporting movement: Meaning, momentum, motives, and materiality. John Wiley & Sons. New Jersey.

|

|

|

|

|

Eccles RG, Saltzman D (2011). Achieving sustainability through integrated reporting in Stanford Social Innovation Review, Summer, pp. 56-61.

|

|

|

|

|

Elkington J (1999). Triple bottom-line reporting: Looking for balance in Australian CPA, 69:18-21.

|

|

|

|

|

ENI (2016). Integrated Annual Report 2016. retrieved 11 December 2017

View

|

|

|

|

|

Ernest and Young (2016). EY's Excellence in Integrated Reporting Awards. A survey of the integrated reports of South Africa's top 10 state-owned entities, retrieved 11 December 2017 from

View

|

|

|

|

|

EU (2014). Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups, retrieved 11 December 2017 from

View

|

|

|

|

|

EU (2017). Guidelines on non-financial reporting (methodology for reporting non-financial information) (2017/C 215/01), retrieved 11 December 2017 from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Frías-Aceituno JV, Rodríguez-Ariza l, García-Sánchez IM (2013). Is integrated reporting determined by a country's legal system? An exploratory study. J Clean Prod. 44:45-55.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gray R (2006). Social, environmental and sustainability reporting and organizational value creation? Whose value? Whose creation?. Accounting Audit. Account. J. 19(6):793-819.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) (2015). Sustainability and reporting Trends in 2025-Preparing the future. GRI's Reporting 2025 Project: First analysis paper, May 2015, retrieved 11 December 2017 from

View.

|

|

|

|

|

Guthrie J, Olson O, Humphrey C (1999). Debating developments in new public financial management: the limits of global theorising and some new ways forward. Financ. Account. Manage. 15(3â€4):209-228.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Guthrie J (2017). Preface. In Katsikas E., Manes-Rossi F. and Orelli R. Towards Integrated Reporting - Accounting Change in the Public Sector, Springer, Switzerland.

|

|

|

|

|

Guthrie J, Manes-Rossi F, Orelli R (2017). Integrated reporting and integrated thinking in Italian public organizations in Meditari Account. Res. 25(4):553-573.

|

|

|

|

|

Higgins C, Stubbs W, Love T (2014). Walking the talk(s): Organisational narratives of integrated reporting, Accounting, Audit. Account. J. 27(7):1090-1119.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) (2013). International <IR> Framework, retrieved 11 December 2017 from

View

|

|

|

|

|

International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) and CIPFA (2016). Focusing on value creation in the public sector, retrieved 11 December 2017 from

View

|

|

|

|

|

IRC of SA (2011). Discussion Paper of the Framework for Integrated Reporting and the Integrated Report Discussion Paper, retrieved 11 December 2017 from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Jensen JC, Berg N (2012). Determinants of traditional sustainability reporting versus integrated reporting. An institutionalist approach. Bus. Strat. Env. 21(5):299-316.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Johannesburg Stock Market (JSE) (2015) Limited Listings Requirements Issue 21, retrieved 11 December 2017 from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Katsikas E, Manes-Rossi F, Orelli R (2017). Towards Integrated Reporting - Accounting Change in the Public Sector, Springer, Switzerland.

|

|

|

|

|

KPMG (2012). Applying Integrated Reporting principles in the public sector, retrieved 11 December 2017 from,

View.

|

|

|

|

|

Liguori M, Steccolini I (2014). Accounting, innovation and public-sector change. Translating reforms into change? Crit. Perspect. Account. 25(4-5):319-323.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mack J, Ryan C (2007). Is there an audience for public sector annual reports: Australian evidence? Int. J. Pub. Sect. Manage, 20(2):134-146.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Milne MJ, Gray R (2013). Whither ecology? The triple bottom line, the global reporting initiative, and corporate sustainability reporting. J. Bus. Ethics 118(1):13-29.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Monfardini P (2010). Accountability in the new public sector: a comparative case study. Int. J. Pub. Sect. Manage. 23(7): 632-646.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Munich Airport (2016). Munich Airport Integrated Report 2016

View (Access 11th December 2017)

|

|

|

|

|

Osborne SP (Ed.). (2010). The new public governance: Emerging perspectives on the theory and practice of public governance. Routledge.

|

|

|

|

|

PWC (2015). Implementing integrated reporting.

|

|

|

|

|

ROSATOM (2017). Public Annual Report, retrieved 11 December 2017 from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Saunders M, Lewis P, Thornhill A (2009). Research methods for business students, 5/e. Pearson Education India.

|

|

|

|

|

Thomson I, Bebbington J (2005). Social and environmental reporting in the UK: a pedagogic evaluation. Crit. Perspect. Account. 16(5):507-533.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Warsaw (2015). Sustainable Development of Warsaw 2014-2015. Warsaw's Third Integrated Report., retrieved 11 December 2017 from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Yin RK (2014). Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 5th ed., Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA.

|

|