Establishing a strong fan base within the inaugural year of a National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Division I Football Program presents many challenges. Tracking consumers and their behavior becomes imperative as sport marketers seek to better understand the first fan adopters of a new program. With new NCAA football programs being established every year, sport marketers of a new program are challenged to not only find a loyal fan-base who will continue to support the program despite win or lose, but find new and innovative ways to grow their fan base. The purpose of this study was to examine attendance demographics and consumer behavior for the inaugural football season at a NCAA Division 1 program. Data were collected (n = 914) from a relatively equal distribution of fan groups (students- 34.8%, alumni- 32.9%, and other- 32.3%) via an in-person survey completed on a tablet interface. Results demonstrate that the level of fandom (temporary, devoted, or fanatic) impacts certain consumer behaviors, including; overall support of the program, media consumption, and game day behaviors.

Marketing for a new NCAA Division I athletic sports program can be a complicated institutional task. Since 2014, 15 collegiate football programs commenced their inaugural seasons within the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) and National Association for Intercollegiate Athletes (NAIA). The introduction of these new programs, with even more on the coming horizon, help indicate the importance collegiate football programs have on campuses across the United States (National Football Foundation, 2014). At the very center of marketing for a new collegiate sport program is the challenging task of not only acquiring a new and devoted fan base, but retaining that fan support season after season (Gray and Wert-Gray, 2011). The first fan adopters of a sports team play an influential role in igniting potential program success by driving attendance and helping establish loyalty to the program (Heere and Katz, 2014). Therefore, it is essential for sport marketers to know who these initial fans are and how they consume. The development of a strong fan base often drives such things as media consumption, merchandise sales, and sponsorship opportunities (Grant et al., 2011). Fan loyalty to a new college football team is not easily established and requires extensive marketing research to reveal demographic, psychographic, and geographic information about the first fan adopters and retention of those fans (Funk and James, 2006; Kelly and Dixon, 2011). Sport management scholars have focused on such concepts as fan satisfaction (Yoshida et al., 2015), brand attachment (Filo et al., 2008), team identification (Lock et al., 2012), social identity (Heere et al., 2011), and fan segmentation (McDonald et al., 2016) aimed to examine, quantify and predict the complex nature of consumer behaviors. Embedded in sport management literature are significant contributions to the understanding of attitudinal processes that drive consumer behavior and fan loyalty of established sport programs. Sport marketers have limited guidance on how a new sport program attracts and develops a fan base in the inaugural year. As a result, the purpose of this study was to explore the first fan adopters of a new NCAA Division I (Football Championship Series) program in the Southeast United States. Of specific note, this university’s football program has been dormant since being discontinued in 2003, and underwent a complete overhaul specific to branding initiatives in recent years. Therefore, the principal investigators of this study delimited and classified this program as a newly established program. Specific to the research foci, this study sought to examine attendance demographics and trends, consumer behavior directly associated with game day travel and attendance, and if consumption varied depending on their level of fandom to the new program.

Theoretical framework

Fan segmentation and consumer behavior, the theoretical framework of this study, were also paired with the concepts of BIRGing (Basking in reflected glory), CORFing (Cutting off reflective glory), and BIRFing (Basking in reflective failure), as they relate to first fan adopters. Knowledge of the first fan adopters is useful to sport marketers, and their consumption habits are particularly important. Building fan connection and loyalty, during the early years is essential for the survival of new teams (McDonald and Alpert, 2007). Marketers are faced with saturated marketplaces and increasingly fragmented customer bases with intense competition for revenue. This calls for a greater focus on consumers through segmentation. Segmentation, as defined by Tyann and Drayton (1987), is the process of “dividing a broad consumer market into sub-groups based on some type of shared characteristic.” These researchers go on to state the aim of segmentation is to identify high yield segments. These high yield segments are of interest to marketers as they are the consumers who demonstrate more loyalty. Segmentation also reveals consumers with potential growth within an organization (McDonald, 2016). Without proper segmentation strategies teams can struggle to effectively leverage limited consumer resources to develop and maintain relationships with various consumer groups (Stewart et al., 2003).

Consumer segmentation

Knowledge about fans, especially those who are classified as first adopters, are essential to sport marketers. Before an athletic program critically examines consumer behaviors on first adopters of a new football program, it is important to first understand the sport consumer, their levels of loyalty, and how they function in conjunction with a new football program (Samra and Wos, 2014). Demographic, psychographic, and geographic information are often collected by the sport organization to be used by marketers to more specifically target their consumers and seek to increase their loyalty and engagement with the organization (Mullin et al., 2014). In Stewart’s (2003) study of consumer typologies, multiple theoretical and practical approaches reveal the value of segmenting consumers. Lewis (2001) also illustrated how segmentation of the fan-base can enhance marketing efforts and result in more loyal fans. As a sector, sports display several unique characteristics: fan involvement with the product, fluctuation of consumer needs and desires, and marketer’s minimal control over the sport product (Tapp and Clowes, 2002). These characteristics have led to special segmentation approaches unique to sport and the support of sports. Mullins et al. (2000) emphasized the importance of value-based segmentation in which supporters are grouped according to their attendance commitment. Results revealed that the more loyal the fan the more games they attended (Mullin et al., 2000). Parker and Stuart (1997) discussed the remarkably high loyalty of football fans compared to customer loyalty in their sectors. They did not, however, discuss possible segmentations of fans according to their levels of loyalty or specific demographics of fans within each loyalty segment. Through segmentation, marketers can further identify sub-groups to target. This type of target marketing increases brand awareness and drives purchase behavior in fans (Fisher and Wakefield, 1998; Wakefield, 2016). The loyalty and identity of fans attending a new football program will be further explored in this paper to help sport marketers better understand fan segments represented during the first season, and behaviors that are similar/different among each of these segments. Marketers understand how important the first adopters are when a new product is released. It has been established that if a new team fails to gain traction in the marketplace in its early years, there is evidence that growth is difficult thereafter (McDonald and Alpert, 2007). Therefore, the early consumers of new products, or in this case, a new football program, play a vital role in driving wider community adoption (McDonald et al., 2016).

Consumer behavior

To be successful in marketing products, professionals must first understand their consumer’s wants, needs, desires, and behaviors. Market research shows that established products and brands offer more in-depth understanding of consumers, whereas newly established brands or products do not have previous consumers or exposure in the marketplace (Grant et al., 2011). This continues to create challenges as marketing professionals seek to understand consumer behavior of the first adopters, in an effort to more effectively develop marketing plans (Greenwood et al., 2006; McDonald et al., 2016). Minimal marketing research has been conducted on first adopters, or those who purchase new products first, but the value of these consumers plays a key role in the success of a new product or sport program (Funk and James, 2001a; Heere and Katz, 2014). To understand sport consumer behavior, one must first understand the term consumer. A consumer is an individual who purchases, or has the capacity to purchase goods and services offered for sale in order to satisfy a need, want or desire. Since this definition is focused on an individual, the marketer must then look at human behavior in order to better understand their consumers. In a report on consumer behavior, Amdt (1976) finds the idea that every thought, motive, sensation and decision made every day is classified as human behavior. Consumer behavior is then defined as the study of human behavior through a consumer role (Belch et al., 2009). Consumer behavior represents specific types of human actions, mostly those concerned with purchase of or engagement with products or services (Amdt, 1976). Additional research revealed a link between human behavior and consumer behavior adopting similar processes whereby individuals decided whether, what, when, where and how, and from whom to purchase goods and services (Hofacker and Malthouse, 2016). Mowen (1993) defined consumer behavior focused on group consumption, studying the buying units and exchange processes involved in acquiring, consuming, and disposing of goods, services, and experiences.

Consumer behavior in sport

Trail and James (2011) proposed that there are four components in the sport consumption process: motivation, activation, external constraints, and post-consumption reaction/evaluation. Motivation for consumption is based on the individual’s personality, needs, values and goals. Different fans consume sport due to different motives; these motives could be utilized as a segmentation variable to better target fans (Trail et al., 2003). Activation of consumption is based on product awareness, interest and evaluation; external constraints are what could prevent sport consumption; and post-consumption is the confirmation or disconfirmation of expectancies (Trail and James, 2011). Additionally, these components of consumption can be exhibited through varying fan levels. To understand sport consumer behavior is it vital to understand how fan loyalty impacts consumption behaviors. Loyalty is “a deeply held commitment to rebuy or repatronize a preferred product service consistently in the future, thereby causing a repetitive same-brand or same brand-set purchasing" (Oliver, 1999). Sport team loyalty is “a psychological attachment to a team resulting in positive behaviors and attitudes toward that team, mirrors brand loyalty in that it includes both attitudinal and behavioral consistency” (Dwyer et al., 2015). Loyalty is often broken down into two categories: attitudinal and behavioral (Funk and James, 2001a; Backman and Crompton, 1991; Dick and Basu, 1994). The extent to which a person holds positive attitudes towards a product or brand is the attitudinal aspect, and the behavioral component is defined by repeat purchase and usage of the brand or product (Chaudhuri and Holbrook, 2001). Additionally, the behavioral component can be measured as the frequency of game attendance, merchandise acquisition, and media consumption as well as, social media usage, wearing team colors, and engaging in game day rituals; while the attitudinal components will focus on commitment and loyalty (Dwyer et al., 2015). While the discrepancy between behavioral and attitudinal components is important in evaluating fans, it is even more important to understand their level of fandom in accordance with their consumption practices.

Sport consumer fan types

Samra and Wos (2014) state that fans as consumers possess emotional attachment with the consumption of objects; they behave as loyal consumers who repeat purchases or insist on staying in the relationship between brands and products, and they establish membership behaviors: co-production and investment. Based on these principles and supporting fan literature, it was established that fans are categorized into three different levels:

(a) temporary fan.

(b) devoted fan.

(c) fanatical fan.

For instance, a temporary fan could be described as a carefree/casual fan, a corporate fan, a social fan, or a less loyal fan (Tapp and Clowes, 2002; Nash, 2000; Sutton et al., 1997; Bristow and Sebastian, 2001). A devoted fan was a term settled on after reviewing articles on committed casual fans, focused fans and traditional fans (Hunt et al., 1999; Sutton, 1997). Lastly, Samra and Wos (2014) coined the term fanatical fan based on literature labeling fans as die-hard fans, fanatical fans, vested fans, passionate fans (Hunt et al., 1999; Sutton et al., 1997). Detailed descriptions of temporary fans, devoted fans, and fanatical fans are next explained.

Temporary fan

A temporary fan is someone whose fandom does not impact their self-concept, their fandom is constrained by time, and once the game, event, or “phenomenon” is over they are no longer motivated to be involved in behavior related to the sport (Samra and Wos, 2014). The casual consumer will only continue attending sporting events if the benefits outweigh the costs of attending the event (Pimentel et al., 2004; Stewart et al., 2003). They will use sporting events as a means for socializing and escaping the realities of life. The purchase behavior of a casual fan tends to be less than that of loyal or die-hard fans (Fairley, 2003; O’Barr, 2012). Thus, sport marketers are constantly seeking ways to increase the level of fandom.

Devoted fan

Next, the devoted fan remains loyal to their team, they are not bound by time, they are attached to the object so much that it impacts their self-concept, exhibit protective behavior, and the consumer is emotionally attached to the object, whether it is deteriorating or not. They cannot be waivered by positive or negative situations they are not impacted by BIRGING or CORFing behaviors, which will be described later in the literature (Samra and Wos, 2014). This fan level has also been described as a loyal fan. This fan is one that will regularly attend sporting events, purchase season tickets, and watch games on television (Agas et al., 2012; Branscombe and Wann, 1992; Crawford, 2004). Even with increased connectivity, their attendance at games can fluctuate and can be affected by promotions, scheduling conflicts, or finances (Tapp, 2004). This type of fan purchases team merchandise, as well as bring others to games as a social event. This group of fans can be a vital revenue source for sport programs, especially if they are bringing non-traditional sport fans to the games (Agas et al., 2012; Garland et al., 2004).

Fanatical fan

Lastly, fanatical fans have an intense loyalty related to their consumption. Their interest in the brand is self-sustaining, they voluntarily engage in behaviors that protect the brand, they exhibit love and remain loyal despite poor performances, they join support groups, receive news, and actively seek more knowledge of the brand (Samra and Wos, 2014; Stewart et al., 2003). This type of consumer could also be called a “die-hard fan”. The classification of a die-hard fan is someone who considers their team part of who they are. Self-identification comes through their fanship and dedication to sports (Garland et al., 2004; Hunt et al., 1999). These fans not only attend games but are also connected via social networking sites and websites to keep up with their team (Ludvigsen and Veerasawmy, 2010). Research suggests that die-hard fans gain self-esteem by identifying themselves with teams and players. This type of fan will spend more resources on team merchandise and tickets (O’Barr, 2012; Shapiro et al., 2013), and if they are not able to attend events they will often purchase exclusive network programs on television to stay connected. Fanatics identify themselves as an extension of the game and team, thus supporting the team despite their record (Reysen and Branscombe, 2010). They are also consumption drivers; they have heavy usage patterns, attract new customers, support the brand financially, and are consistent, persistent and resistant to any attempt to reduce their level attachment by other brands. Fanatics feel as if the team and fans are part of their extended family, and often, feel that they owe a certain level of devotion to the organization (Samra and Wos, 2014; Wang et al., 2013).

New football program and first fan adopters

With the creation of a new collegiate Division 1 football program, athletic departments have the challenge and opportunity to establish a new fan base. Research surrounding new sport programs and fan support is of upmost importance when dealing with new programs where fan loyalty may not yet be established. A better understanding of fans can help cultivate marketing strategies for new programs seeking to establish a strong fan base. It is vital to study why fans support teams, especially when a winning record is not likely going to be available to motivate fans. The importance of building and maintaining a loyal fan base with connections stemming beyond on-field performance has become a prominent area of research within the sport management literature (Doyle et al., 2013; McDonald, 2010; McDonald et al., 2013).

Formation of the fan

Funk and James (2006) found that consumer evaluations should only come after the consumers have been exposed to the sport product, but Heere and Katz (2014),conducted a study on a new collegiate football program and found that fans identified positively with the team, even though they knew very little about the newly formed team. Additionally, Heere and James (2007) suggest that respondents can positively identify themselves with a new collegiate football team because of a strong connection to the university, even before the season even starts. It has also been found that attending games together, using the university as a central reference for identity, gives fans an opportunity to bond based on common social interests (Clopton, 2009; Swyers, 2005). Also, alumni were more likely to identify with the team because the new program would allow them to engage with the university, and students correlated the presence of a football team with their identity to the university (Heere and Katz, 2014). “Once students have experienced the excitement of attending a game, it will influence their identification with the team, which could increase their likelihood of attending games throughout their college years and beyond” (Shapiro et al., 2013). In addition to university connectivity, findings suggest that to attract fan support a team should leverage existing social identities: team players, team organization, star players, well known head coaches and respected administration (Lock et al., 2011; Kunkel et al., 2016).

Fan segmentation

McDonald et al. (2016) established different types of fans that can be found in a new sport program. Similar to fan categories above (that is, temporary, devoted, and fanatical), it was possible to rate types of fandom in a new sport program. The first fan adopters were broken down into five segments: instant fanatics segment, community-focused segment, independent triers segment, social theatregoers segments, and casuals segment. McDonald et al. (2016) found that instant fanatics accounted for 30% of the sample, with only 12 months of involvement. Of this 30%, these individuals had the highest levels of connectivity, public evaluation, and cognitive awareness. These fans are likely to become season ticket holders (Funk and James, 2001b) advocates for the organization, drive fan rituals and co-created behaviors, and will be a large part of the characterization of this new fan group. These fans will often have high levels of consumption and attitudinal loyalty (Dionísio et al., 2008; Alexandris and Tsiotsou, 2012; Tapp and Clowes, 2002). Next, McDonald et al. (2016) established a community-focused segment within the first adopters. This segment was attracted to the team because it was good for the community. Corporate social responsibility was most likely a factor for these fans as its activities have a positive impact on an organization’s reputation and can increase word of mouth and merchandise consumption for the sport organization (Walker and Kent, 2009). A motivator for this segment could also be the overall economic impact that a new football program could make for the community. Beyond the game itself, many fans state that they also participate in activities outside the sporting event setting, such as: dining out, shopping, attending other sport events, and experiencing the night life (Pennington-Gray et al., 2002; Graham, 1996; Irwin and Sandler, 1998).

Additionally, the social theatergoers fan segment was made up of males who were connected to the sport, but not necessarily to the team. These first adopters may still have existing fandom for other teams, which may prevent higher levels of connectivity (McDonald et al., 2016). Though these fans did not have the level of identification sport marketers would prefer, they are still an integral part of the segmentation process. They were active participants and consumers, and their consumption was in relation to social connections and group affiliation (McDonald et al., 2016). Previous research shows that group affiliation is connected to the nature of sport spectatorship (Wann et al., 2008), it has been found that fans prefer game attendance as a group (Aveni, 1977), and fans are influenced by significant others and social norms when deciding on game attendance (Cunningham and Kwon, 2003). The last, and arguably most intriguing segment, is the independent trier. McDonald et al. (2016) states that these first adopters attended games, but were not as connected as the instant fanatics and provided the lowest public evaluation ratings. Low public ratings may be a form of ego protection that is often common in teams with unsatisfactory attributes (Madrigal, 1995), though past studies show that vicarious achievement is not as relevant with a new team as it is with an established team (Lock et al., 2011). This type of fan rejects the idea of supporting a team for social connections, limit their involvement in fan-related activities, and consume the product for self-sufficiency (McDonald et al., 2016). It will be challenging to increase their connectivity with the organization through attitudinal or behavioral components.

Emerging constructs

As previously stated, ego protection seems to be an important part of fandom. Belonging to a team that will be successful is beneficial, and much research has been conducted on the phenomenon of the sports fandom focuses on why fans have the desire to belong to their team of choice (Joncheray et al., 2014; Martin et al., 2014; Sanderson, 2013). Two concepts in research include: Basking in Reflective Glory (BIRGing) and Cutting off Reflective Failure (CORFing). BIRGing is described by Tapp (2004) as the tendency of individuals to publicize their connection to successful others, without contributing to the others success (Cialdini et al., 1976; Tapp and Clowes, 2002; Daniel et al., 1995). On the other hand, CORFing is defined by Wann and Branscombe (1990) as the moment an individual switches his or her team loyalty or loyalty of a sport organization in part because the team or organization is not succeeding. Beyond ego protecting concepts, there are two newer concepts that extend from the existing theories: Basking in-spite of Reflected Failure (BIRFing) and Cutting Off Reflected Success (CORSing) (Campbell et al., 2004; Jensen et al., 2016). For CORSing (cutting off reflected success), team success might be positive, yet fans’ association may be negative. Here one can see fans disassociating themselves from a winning team. In CORSing, a fan is managing their self-image through an expression of individualism (Campbell et al., 2004). Research in this area found team performance might be negative, yet fans’ associations may be positive. Basking in spite of reflected failure may be deemed loyalist behavior, wherein a fan remains loyal to the team. Here loyalty is described in terms of blend of attitude and behavior that can be measured by the degree to which one favors a certain product (Pritchard et al., 1999). While teams may be losing, fans in this case are reveling in the loyalty, camaraderie, and other alternative reasons for fan-ship (Reysen and Branscombe, 2010). Based on this information it seems fans may support a team for reasons beyond solely a successful on-field sport product, and are influenced by such things as: university identification, community support, and social connections. More studies are needed to strengthen these two emerging constructs as they pertain to new sport programs and the establishment of strong fan bases. Because of the gap in the literature, this study sought to explore fan attendance trends and consumer behavior related to the establishment of a new NCAA Division 1 Football Program.

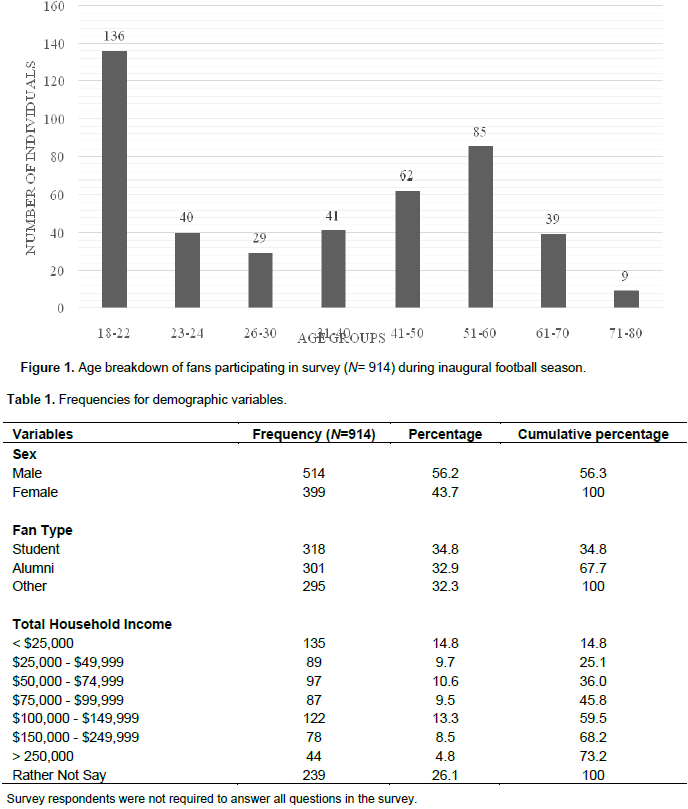

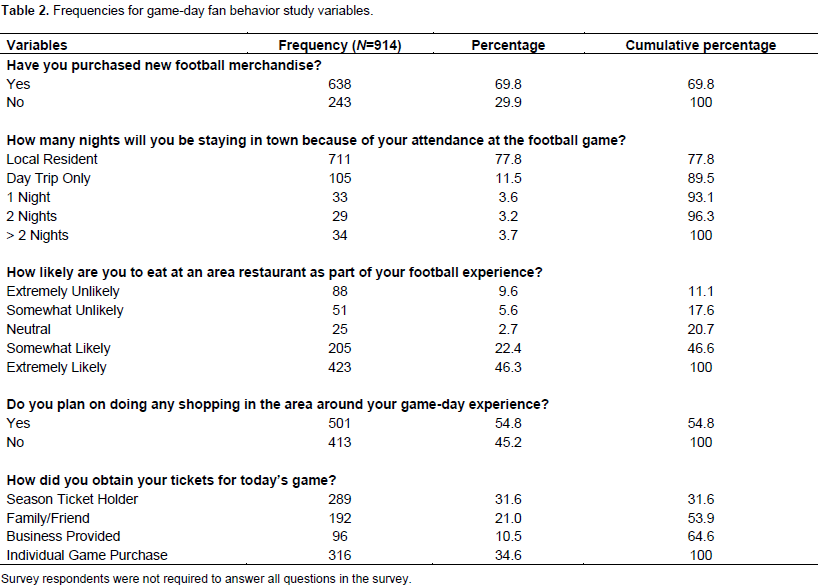

Results were analyzed on IBM SPSS 23.0 and were computed using chi-square, t-test, and correlation, as appropriate. Of the 914 respondents, 56.2% (n = 514) were male, and 43.7% (n = 399) were female, with a mean age of 36.1 (SD = 16.3). Ages of participants ranged from 18 to 80 years with the largest group in the 18 to 22 age range (Figure 1). Fan identification gave participants the opportunity to identify with a specific group. Of the 914 total participants, there was a relatively even distribution between the three groups, with 34.8% (n = 318) of the fans identifying as being a student, 32.9% (n = 301) as alumni of the university, and 32.3% (n = 295) classifying as other (Table 1). The classification of other represented fans who did not classify as being a current student or alumni, and could constitute as local community members, business professionals, parents of the athletes, etc. Participants were also asked to classify themselves by total household income. Though, a substantial proportion of the participants (26.1%) declined to answer the question, there was a very large distribution of income classifications with the largest proportions of reported total household income being (a) < $25,000 (14.8%), (b) $100,000 - $149,999 (13.3%), and (c) $50,000 - $74,999 (10.6%) (Table 1). Descriptive frequencies were then run to compare levels of reported income between the student fan base and the alumni fan base. Data revealed 38.1% (n=115) of alumni reported a household income level greater than $100,000. Less than $25,000 was the most popular household income category reported by students, accounting for 32% (n=109) of students who participated.

Game day impact and consumer behaviors

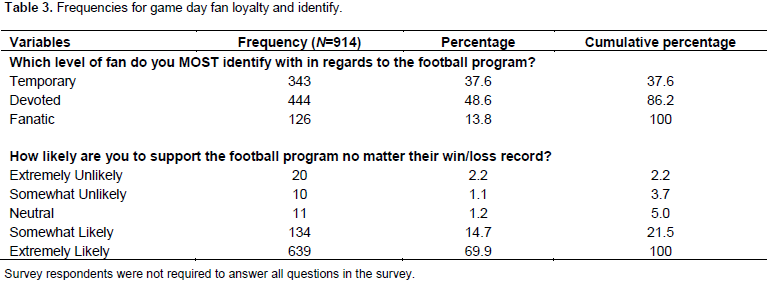

Fans were asked several survey questions that addressed game day fan behavior specifically linked to attendance of a home football game. With the announcement of the new football program, 69.8% (n = 638) of fans stated that they purchased new football merchandise (Table 2). Descriptive analysis revealed different consumption behaviors among the different fan types with fanatics (90.5%, n = 114) reporting the highest consumption of new football merchandise and temporary fans (56.4%, n = 145) representing the lowest fan type to purchase merchandise. Of those fans surveyed, 77.8% (n = 711) reported as being local to the area and did not seek accommodations to attend a home game. The majority of the non-local residents (11.5%, n = 105) stated that their travel to the game was only a day trip. Only 10.5% (n = 96) of participants stated that their travels would have them staying at least one night at a local hotel. An ANOVA was run to compare number of nights stayed in town with level of fandom reported. This statistical analysis revealed F (4.906) = 1.416, p = 0.227, no significant difference when looking at level of fandom and nights spent in town prior to or after a football game. When asked about dining at a local restaurant, 79.3% (n = 628) of fans stated that they were somewhat or extremely likely to dine at a local restaurant associated with their game experience.

In addition, 54.8% (n = 501) of fans reported that they would be shopping locally as part of their game-day experience. These finding suggest that though most of the fans were regional to the university, there was still a high chance of restaurant consumption and shopping associated with game attendance. Finally, fans were asked about how they obtained their game tickets. The two largest populations to purchase game tickets were season ticket holders (34.6%; n = 316) and individual game purchases, with 21% obtaining tickets from a friend or family member, and 10.5% obtained tickets through their business (Table2). Independent t-test examining likelihood of local dining (1-5; highly unlikely-highly likely) and fan type showed that there was a non-significant difference between students (M = 4.0, SD = 1.27, N = 259) and alumni (M = 4.11, SD = 1.37, N = 274) , t (531) = -0.888, p = 0.531, a non-significant different between students and others (M = 4.01, SD = 1.4, N = 259), t (516) = -0.033, p = 0.974, and a non-significant difference between alumni and others, t (531) = 0.815, p = 0.416. A chi-square test for independence showed there was a significant relationship between fan type and plans for shopping locally (yes/no) as part of their game-day experience the χ2 (2) = 9.12, p = 0.01, and that the others and alumni groups had a higher percentage of indication towards shopping compared to that of students.

Fan loyalty and identity

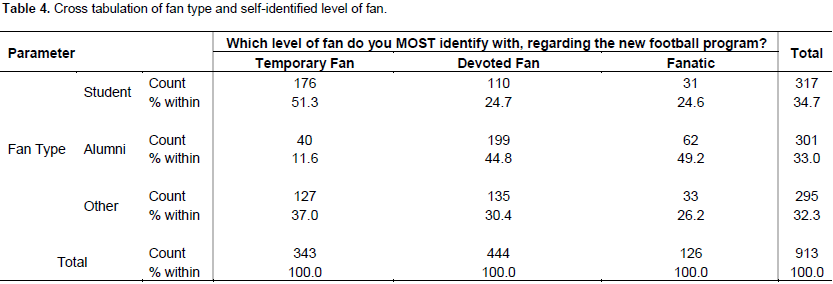

Fans were asked what level of fandom they most identify with. Results showed that two main groups demonstrated to take up the majority, temporary (37.8%) and devoted fans (48.6%), with fanatic (13.8%) having a smaller number of self-identified respondents (Table 3). In addition, a very high rate of participants (84.6%) stated that they were either extremely likely or somewhat likely to support the football program regardless of win/loss record. An independent t-test examining likelihood of continued support regardless of win/loss record (1-5; highly unlikely-highly likely) and consumer type showed that both alumni (M = 4.78, SD = 0.65, N = 287) and the other group (M = 4.74, SD = 0.74, N = 265) had a significantly higher likelihood for continued support of the football program compared to that of students (M = 4.5, SD = 0.93, N = 262), t (547) = -4.1, p< 0.001, t (525) = -3.2, p = 0.001. There was a non-significant difference between likelihood of team support between the alumni and other groups, t (550) = 0.696, p = 0.487. A follow-up independent t-test on the likelihood of team support between the males and females was found to have non-significant difference t (812) = -0.271, p = 0.787. Descriptive analysis examined differences among levels of fandom and overall support of the new football program. Results indicated 61% of those who identified themselves as temporary fans were extremely likely to support the new football program despite winning record. Fanatics (89.9%) represented the highest percent of those reporting they were extremely likely to support, with devoted fans (80.2%) indicating high levels of support as well (Table 4). A chi-square test for independence showed there was a significant relationship between fan type and level of fan participants most identify with the χ2 (8) = 138.25, p < 0.001, and that the others and alumni groups had a higher percentage of indication towards the fan classification of devoted fan, where students most identified with the classification of temporary.

Fan and media connection to a New Football Program

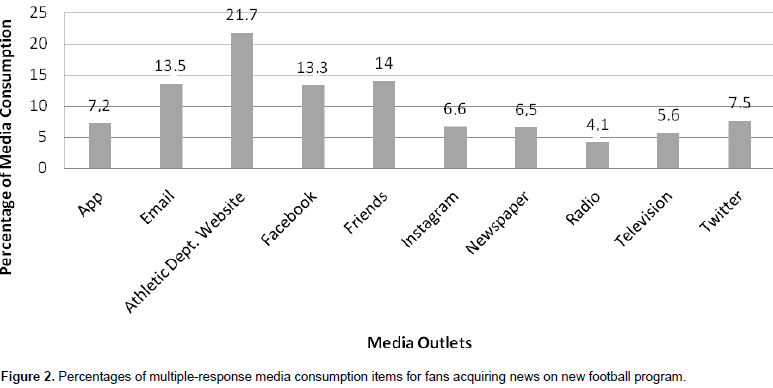

The last area participants were asked to address howthey received information and updates about the new football program. Fans were given a multiple-response survey item asking them to choose all of the media channels they used to acquire news and updates on the new program. Overall, the largest number of respondents (58.1%) reported that the university website is where they go to get their football updates and news, followed by Email (36.2%), Facebook (35.5%), through friends (37.4%) (Figure 2). Fans reported that they sought news of the football program the least from the university app, Instagram, newspaper, television, radio, and twitter. Further investigation regarding media consumption and level of fandom revealed all levels of fandom reported the website as the most utilized channel of communication. In continuing with comparing fan type with media consumption, “friends” was the second most common form of media consumption among temporary fans (39.8%, n = 135), and devoted fans (48.3%, n = 164), while fanatics (51.6%, n = 65) reported Facebook as the second most common channel. Among all fan types, radio was reported to be the least utilized method used when fans sought information about the new football program.

This study provides insight into the first fan adopters of a new NCAA Division I (FBS) Football Program at a university in the Southeast United States, in an effort to examine these fans and their level of support. Literature that focuses specifically on fandom of new sport programs is lacking. Therefore, this study provided information about consumers attending home games during the first football season. This information can be used by sport marketers to more efficiently target current and future consumers as well as enhance game-day experiences. This information can also be used to further the body of knowledge in the area of consumer behavior and new sport programs. When looking at the demographic information of the consumer in attendance, it was no surprise that the largest group represented by age was 18 - 22 year olds. It is important to note that research relating to the benefits of adding collegiate football programs at universities state that the student body are more likely to become first fan adopters because of their established identity with the university. This can also be said of faculty, staff and alumni of the university (Warner et al., 2011). The current study also found the second largest group represented were the alumni of the university. Heere and James (2007) state the importance of establishing a fan base that will not only attend, but will actively consume. While student support is of upmost importance, the alumni group will most often have more disposible income and therefore become a target consumer in the eyes of sport marketers (Heere and Katz, 2014). This study found 38.1% of participating alumni reported a household income level greater than $100,000. This information can be used by marketing teams to develop more effectient marketing strategies to target this group and increase fan consumption. When looking at game-day impact to the local community without segmenting social groups, the first adopter fans indicated they were likely to purchase football merchandise (68.9%), dine in restaurants (79.3%), and even shop in the area (54.8%).

McDonald et al. (2016) states the first adopters of new products play a vital role in the community coming on board and buying in. This study revealed initial fans were willing to consume on multiple levels prior to exposure of the new football program as a product. This information is not in line with existing literature which states that consumers most often need exposure before consuming the product (Funk and James, 2006). However, literature surrounding consumer behavior suggests that if an existing identity that is tied to a new product can be tapped into, fans will more willingly consume and identify with the product because of the existing identity (Lock et al., 2011). In the case of this study the university was seen as the existing identity for both the students and alumni, which made up the two largest groups in attendance. The study revealed differences in consumer behavior and game day impact in regard to level of fan the participants claimed. The current study reported fanatics (90.5%) as engaging in the highest level of merchandise consumption, with temporary fans (56.4%) representing the lowest amount of consumption among the different levels of fandom. Literature surrounding fandom would agree with this report, as fanatics are seen as zealous fans who continue to consume on a grander scale when compared to fans who report lower levels of fandom (O’Barr, 2012; Shapiro et al., 2013). Fan segmentation was a key in uncovering the loyalty and commitment of the first fans of the new football program. Fans were asked what level of fandom they most identified with and the results indicated the highest percentile recorded was devoted fan (48.6%); this was an interesting finding as it does not fall in line with some existing literature which states that exposure to a new product needs to occur before fans will actively identify with the product (Funk and James, 2006). As stated above, in the case of this research study the university can be seen as an existing identity and therefore we can point to Lock’s et al. (2011) literature that suggests as long as there is an existing identity than initial fan, adopters are more likely to support.

When looking at fandom and level of support, an extremely important finding from this study was a very high rate of participants (84.6%) who stated that they were either extremely likely or somewhat likely to support the football program regardless of win/loss record. Tapp (2004) discussed the terms BIRGing and CORFing in which fans either Bask In Reflective Glory or Cut Off Reflective Failure. In the case of this study, neither of these popular terms used in sport management literature fit, however, a newer coined term BIRFing, or Basking In Reflective Failure, was introduced by Campbell (2004). Literature states the importance of a strong fan base in the success of a new football program because a winning record is not likely in the first few seasons (Heere and Katz, 2014). Participants in this study revealed their willingness to remain loyal fans of the new football program despite the uncertainty of success. Researchers also looked at level of fandom and overall support of the program. Not surprisingly, fanatics (89.9%) reported the highest levels of support of the new football program despite win/loss record. Again, this is in line with previous literature which suggests the stronger the fandom the more likely the fan will continue supporting a team year after year (Funk and James, 2001b; Dionisio et al., 2008). A surprising finding was the level of support by temporary fans, with 61% reporting this support despite win/loss. Funk and James (2006) suggest consumers need prior exposure before establishing loyalty or participation. Temporary fans suggesting this level of support does not agree with previous literature. One justification for this level of support was the fact students most highly identified themselves as temporary fans, which suggests this fan group has an existing identity with the university. This would then agree with Heere and James (2007) suggesting an established identity may result in more loyal support of a new program.

After segmenting the data, results showed a significant difference in loyalty among groups, specifically among the alumni support and student support. Alumni indicated a much higher likelihood of remaining loyal to the program despite win/loss record, while students were not as willing to provide the grace period for the new football program. From a marketing standpoint, this is of importance as sport marketers are seeking not only ticket holders (which student tickets were free in this case), but are seeking first fan adopters that will consume multiple products associated with the program (Heere and James, 2007). These findings suggest the alumni, which have the expendable income, will also be the social group that most positively impacts the revenue generated by the new program. Literature states that student body fanship is still of upmost importance as their adoption of the new football program in turn impacts the overall community involvement with the program (McDonald et al., 2016). Participants were asked to address how they received information and updates about the football program. Of the many options given, the study revealed that the largest number of fans (58.1%) were using the athletic department website as a means of retrieving information, followed by Social Media (36.2%) and Email (35.5%). Radio (4.1%) and Television (5.6%) were found to be utilized the least when fans were seeking information about the football program. This information is vital for effective marketing efforts within the university Athletic Department. Breaking through the cluttered marketplace which is full of communication outlets is a key to developing a successful marketing plan (Lucian, 2014). Researchers also looked at media consumption based on level of fan reported and found no significant differences in media consumption behaviors. From a marketing perspective, the knowledge gained about first fan adopters and how they consume media can aid in the development of the most utilized media platforms, thus providing information on the most appropriate platforms. Trail et al. (2003) suggest this type marketing approach may aid in activation of consumption for potential consumers, or in this case, first fan adopters.

Managerial Implications

Despite evidence that suggests initial fan adoption of new sport programs is nearly impossible to accomplish, and that only established brands and teams with winning records tend to have the loyal fan bases, this study indicated that fans did support the new football program. According to McDonald (2016), these types of first fan adopter are labeled “instant fanatics” who form a strong fan base for new programs. This information can be useful to Athletic Department personnel as they continue their efforts in establishing such fans-bases through fan segmentation and creation of tailored marketing efforts to reach targeted groups and move them up the fandom scale. Specifically, marketing efforts can be impacted by knowing who the first fan adopters are of a new product. It involves not only knowing who these fans were, but also their consumer behavior intentions, which elude to purchase of merchandise, restaurants, and shopping. Knowing the willingness of first fan adopters to consume beyond purchasing tickets could aid Athletic Department personnel focused on economic impact and sponsorship involvement within the community. This could also significantly impact fundraising efforts for those seeking to launch a new sport program. Businesses and communities may have more confidence in supporting such initiatives because fans not only support by attending, they supported financially as well. McDonald (2016) labeled this segment of fans “community-focused” and found them to be supportive of new programs. By segmenting the early fans, athletic departments can tailor marketing campaigns to better align with how each target market consumes (socially, media, purchases, dining, etc.).

Limitations and future research

While this study served to provide an overview of the first fan adopters of a new NCAA Division I Football Program, and it was successful in doing so, there were some limitations that need to be addressed. First, the participants for this study were limited to those tail-gating prior to home football games. Another limitation was kick-off time. With data collection taking place before kick-off, at tail-gating sites, the collection process was impacted negatively by early kick-off times that took place. This study only targeted fans before the competition, not after, which could have provided more in-depth analysis of their experiences. Another limitation was site location of the inaugural season being at a stadium that was office-campus on a local high school campus. Research suggests greater stakeholder support when sporting events are on campuses, tying in sense of community theoretical frameworks (Warner et al., 2011). The survey tool was a limitation and needs further review due to low factor analysis reporting. While researchers understand this limitation, the format of the survey, which allowed participants to mark multiple answers on a single question, may be reason for the low factor analysis scores. The coding of these answers may have lent to the low scores as well. However, this format also allowed for further investigation surrounding identity. Future research would include further investigation of the survey tool and reliability. An on-site follow-up questionnaire in order to address some of the limitations and gain a deeper understanding of consumer experiences will also be an opportunity for future research. More in-depth questioning of fan behavior and loyalty would be a key in applying the information gathered to the concepts of CORSing and BIRFing. This particular football program will be building a new stadium on campus in the near future; therefore, a follow-up study focused on the fan-base and fan loyalty would provide insight into the differences in demographics, level of support, among other information that would add to the body of knowledge in the consumer behavior and fan identity, as well as provide Athletic Department personnel with important information regarding the new stadium and tying in “sense of community” theory.