ABSTRACT

Uganda is among the most developing countries in Africa where astronomy education and outreach activities are at infant stages. Although Uganda has a long history of organized ethnic groups and cultures, record of cultural astronomy or its exploration is scanty, a challenge that this paper tries to address. A qualitative research design was adopted with emphasis on holistic description of primary data or information. Four ethnic groups, sampled from Central, Eastern, Northern and Western Uganda were explored, for which data were collected using questionnaires and interview guides. Most of the respondents were purposively sampled or hand-picked because they were either informative or had required characteristics. The commonly known visible celestial objects are the sun, moon and stars, all considered unique in characteristics. The moon and stars are believed to influence weather changes and socio-economic activities. The majority of stars are known to be smaller and very far away, with the bigger stars having names. The picture of a human being is famously recognized on the face of the moon. The ethnic groups still believe that the earth is flat and the sky is round with a diameter equal to the length of the earth.

Key words: Astronomy, ethnic groups, celestial objects, constellations, local names, myths.

The mission of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) is to promote and safeguard the science of astronomy in all its aspects (Chapman et al., 2015). On a dark-clear night, at a distance far from city lights, the sky can be seen in all its splendour (Karttunen et al., 2017). It is interesting to understand how the many lights in the sky have affected people throughout the ages, from using them to track the different seasons to relying on them to navigate thousands of miles on the open ocean, as well as timekeeping and noting fertility cycles (Karttunen et al., 2017; Ghosh, 2019; Urama and Holbrook, 2009). The ancient people saw figures traced by objects in the night sky that were related to religious myths and omens sent by the gods. However, a couple of millennia ago saw the real astronomy starting to evolve, separating itself from religions and astrological superstitions (Karttunen et al., 2017).

Astronomy is basically the study of celestial bodies, and it regards the subject of where and when a celestial body can be observed. According to Campion (1997), cultural or traditional astronomy is the use of astronomical knowledge and beliefs so as to inspire and inform social forms and ideologies.

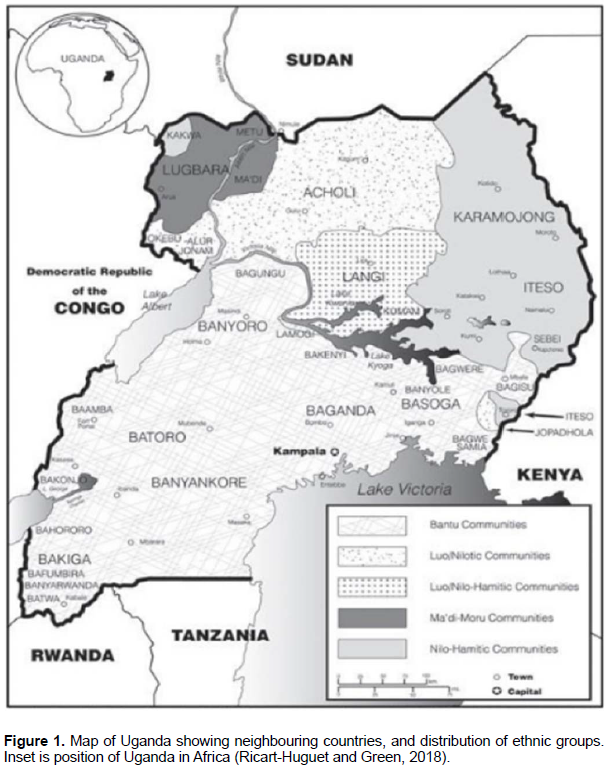

African cultural astronomy is rich with mythical figures and divination methods that utilize observations of celestial bodies, and many other sky-related beliefs and traditions (Urama and Holbrook, 2009). It is entwined with religious beliefs and practices, agriculture, folklore, and social hierarchies (Holbrook, 2007; Urama and Holbrook, 2009). The Egyptians associated Sirius with the goddess Isis, and used its location to predict the annual flooding of the Nile (Ghosh, 2019). According to Urama and Holbrook (2009), one of the greatest challenges of most African astronomers today is being able to make local African world views more scientific, to link them to other world views, and to demystify the mysterious heavenly bodies of antiquity. The authors state that one of the strategies for trying to bridge the gap between traditional and modern astronomy is to reinterpret myths using the scientific lens of modern astronomy. This can show that scientific reasoning is not something new and not divorced from our life and culture. Uganda, the Pearl of Africa, is located in East Africa and lies across the equator (Sejjaaka, 2004; UBOS, 2006). From “The 2002 Uganda National Population and Housing Census Report” (UBOS, 2006), the country is about 800 km inland of Indian Ocean. It lies between 1° 29′ South and 4° 12′ North latitude, and 29° 34′ East and 35° 0′ East longitude. In addition, Uganda is a landlocked country, bordered by Kenya in the east, South Sudan in the north, Democratic Republic of Congo in the west, Tanzania in the south, and Rwanda in south-west. Figure 1 shows the map of Uganda and its position in Africa. Uganda has an area of about 241,038 km2.

Classic Africa Safaris (2020) notes that the inhabitants of the present day Uganda were hunters and gatherers, until about 1700-2300 years ago when the Bantu-speaking populations from Central and Western Africa migrated into the south of the country, with iron-working, and social and political organization skills. In about 120 A. D., the Nilotic people who were cattle keepers and subsistence farmers entered Uganda from the north (Classic Africa Safaris, 2020). According to Amone (2015), Uganda has about 56 ethnic groups, the largest being the Baganda who occupy the northern shores of Lake Victoria. All cities and towns of Uganda as well as state institutions are known for high levels of heterogeneity and the country’s politics has been a reflection of its ethnic plurality (Amone, 2015; Ricart-Huguet and Green, 2018; Government of Uganda, 2005).

This makes Uganda fit within the context of East Africa, which is a multicultural region with diverse ethnic composition and comprises a number of independent states (Kasujja et al., 2014).

Following from Sasso Uganda Safaris (2020), the cultural groups in Uganda, at the time of colonialism, could conveniently be divided into four broad linguistic categories namely; the Bantu, Luo, Ateker and Sudanic. The Bantu constitute over 50 percent of Uganda’s total population and comprise; Baganda, Banyankore, Banyoro, Bakonzo, Basoga, Bakiga, Bafumbira, Batooro, Bamba, Batwa, Banyole, Basamia, and Baggwere. They generally occupy the east, central, west, and southern Uganda. The Ateker people, also called Para-nilotics or Nilohamites, are found mainly in the north, east and north-eastern Uganda. These comprise the Langi, Karamojong, Iteso, Kakwa, and Kumam. The group traces its origin in Ethiopia and is said to have been one people. The Langi are unique in that they lost their Ateker language and culture and resorted to Luo. The Luo is, however, an extensive family that spread all over East Africa. The Luo group in Uganda includes the Alur, Acholi, and Japadhola. The Alur are settled in West Nile, Acholi in Northern Uganda, and Japadhola in Eastern Uganda. The Sudanic people are speakers of West Nile languages, comprising; the Madi, Lugbara, Okebu, Bari, and Metu. They trace their origin in Sudan but their cultures and language indicate that they have become completely detached from their places of origin. The cultural groups reported in this paper are; Baganda, Bagisu, Banyoro, and Langi.

Uganda is among the most developing countries in Africa where Astronomy education and outreach activities are at infant stages, and perhaps not prioritized. This paints a bad image of Uganda, given that cosmogony mythologies of many ethnic nationalities of Africa show that Astronomy, among the sciences, has the deepest cultural roots. On 28th May, 2019, Hayley Roberts (a PhD student from Australian National University), on a yearlong data collection visit to Kibale National Park in Western Uganda, pointed out that his local field assistants from Kyanyawara area have never had a chance to see any astronomical objects through a telescope. To date, there is scanty or no record of Cultural Astronomy in Uganda. This is embarrassing given that Uganda has a long history of organized ethnic groups and cultures, and that there is a growing number of professional astronomers in the country, and Modern Astronomy teaching and research are ongoing in a number of universities. This challenge propelled the study leading to the content of this paper. During data collection process, it was evident that most Ugandans crave for telescope observations of the moon and stars, and the scientific explanation of what they see from time to time. It is hoped that this study will be supplemented by an outreach programme that will bring relief to members of the indigenous population.

It was appropriate to identify prominent planets, stars, constellations, and other celestial objects that may be of public interest, and this was achieved by the use of star map (Ghosh, 2019) and interactive star charts that provided whole lots of stars and planets visible in a given month or season. The brightest planets, stars and constellations were purposively sampled for the study. There are about eighty-eight stellar constellations (Koontz, 2002; Ghosh, 2019), and at least twenty are clearly visible and contain very bright guiding stars.

A qualitative research design was adopted and emphasis is on holistic description of primary data or information. This mostly employed ethnographic research design, to explore the four ethnic groups, sampled from Central, Eastern, Northern and Western Uganda, respectively, in order to understand, describe and interpret their perspectives of celestial objects. This was an exploratory research with unknown variables, so only context was required.

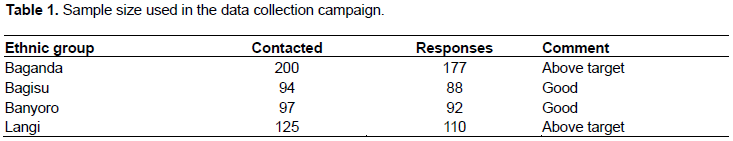

The study also employed both probability sampling and non-probability sampling. In probability sampling, clustering was considered, where each cluster comprised a homogeneous unit or ethnic group. In non-probability sampling, the respondents were purposively chosen because they were either informative or had required characteristics, that is, the respondents with relevant information were hand-picked. In addition, snow-ball sampling was used, where key informants were asked to nominate other people who could be contacted for the information desired. Being the first of its kind, the study considered to contact 100 members of each ethnic group for responses. These comprised 30% women and 70% men, aged 25 years and above. The motivation to have more men was based on the fact that men are usually members of a given ethnic group right from the time they are born, but women may join from other ethnic groups because of intermarriages. Table 1 gives a summary of targets realized during the implementation. The Baganda received the lion’s share because of proximity.

The data collection methods and instruments employed were mainly interviews (interview guides) and questionnaire survey (questionnaires). During the interviews, the respondents were orally questioned either individually or in groups, and their responses recorded during or after the interviews. In questionnaire survey, written questions were presented to respondents to answer in written form, the respondents either being gathered in one place, or contacted via email with clear instructions to fill the questionnaires. Demographic information was obtained from respondents, which included: gender, age, occupation, religion, ethnicity, and place of origin, among others. The respondents identified themselves with Anglican, Catholic, Islamic, and Born Again faiths. Most of the respondents from which relevant information were obtained were aged between 45-80 years. Members of this age group constituted about 80% of those that were approached for the survey, and such a percentage was justified by the experience and/or acquaintance with the cultures. The mass of raw data collected was analyzed qualitatively, since the data were in natural setting with no numerical values. To understand the data, written information was read and re-read several times. The information were categorized to identify any patterns (ideas) and organized coherently.

Onset of cultural perspectives

Visible and invisible objects

Among the Baganda, most of the things seen in the sky (ebyenkunejje by’olubaale) are light giving objects. Their common name is ekyomubwengula. Most traditionalists believe that celestial objects are spirits of the first people; Kintu, Nambi, Gulu, and Walumbe, among others, while the modern Baganda consider celestial objects as God’s

creatures. One traditionalist had these to say:

Those many things you see in the sky are spirits of our ancestors. I believe my late father is one of them. Heaven is above...Unfortunately, so many people have died that you can’t tell from the sky who your relatives are. When we die, we will join them and people on earth will see us twinkle.

Some of the objects seen in the sky have names, for example, the sun, moon, stars, galaxies, shooting stars, and clouds. The Bagisu generally know heavenly bodies as consisting of the sun, moon, stars, clouds and planets. On the list, the Banyoro add the rainbow, mist, and meteorites, and most of them believe everything was created by God, and the earth considered the place of humans, knowledgeable and part of God’s knowledge. Similarly, the Langi tribe considers that celestial bodies mostly seen and known are the sun, moon, and stars, adding that the line of the Milky Way is at times visible.

The four ethnic groups considered also believe that there are many other objects or bodies in the sky which are unseen. These may include distant objects that cannot be seen by the naked eye, but air is unseen yet around us. Some Baganda think that there could be aliens somewhere in space. The Banyoro consider mainly spiritual things as unseen, which include; God, angels, ghosts, and earthquakes, adding also wind and sound. They believe that the Creator has made too many things for human to see and know all. In addition, there exists the heaven of an old woman. Similarly, the Langi focus on spiritual beings, regarding that there are evil spirits in the sky day and night, that keep descending to the ground to disturb humans. Other spirits, angels and God take up their place in the sky. In addition, some Langi consider that there are communication lines and waves that cause linkages in communication. An inquire of this nature was posed:

Can you imagine...how is it that we can listen to Capital FM from here? If there were no lines, we wouldn’t! Tuning is like closing some lines and allowing one, by trial and error...But you people of science may have something else.

Most members of the ethnic groups have not seen any of the celestial objects using any instruments because such instruments are rare, or there are no substantial outreach programmes. However, during solar eclipses, some people have used water in a basin and tinted glasses to view the sun. Some Muslim members have used milk to observe the moon. Only a few members of the ethnic groups have used a telescope at least once.

Desire for scientific explanation

Watching the stars and moon interests most members of the ethnic groups, notably their appearance, arrangement and spacing. Besides, stars twinkle in different sizes and colours, and they follow you whenever you move. Some Baganda wonder how big the stars are - yet they are seen as very diminished and give out light continuously. The moon changes brightness, shape and size, and possesses cool light. For the Bagisu, the stars and moon provide some light that removes total darkness during night time, and patterns formed by the stars are amazing. The Banyoro consider that stars have black centres and light on the outskirts, and the moon leads to changes of things due to its power. They also recognize the appearance and disappearance of shooting stars from north to south, and that there are so many stars in the sky. The Langi consider that looking at the many stars glittering with different intensities makes you trust your eye sight, and the fact that they do not collide could mean that there is a big cosmic order. Generally, the pattern, orientation, structure, size, and colours of stars and moon are breathtaking and leave a lot to be desired.

Culturally, most members of the ethnic groups receive explanation and guidance on the visible celestial objects from community elders and parents, with the Banyoro adding fore tellers and healers who always observe the changes of the moon. However, those who have gone through formal education and religious formations have been guided by teachers in schools and lecturers in institutions. Traditionalists among the Baganda believe that the appearances of objects in the sky are related to seasons, fortunes, disasters, or natural occurrences of events, which could be joyous or sorrowful. Some curious Bagisu feel that scientific guidance is still lacking on the things they see in the sky. The Langi elders say that the Milky Way (Apokipiny) separates drought and rainfall periods.

The majority members of the ethnic groups express high interest in knowing more about the earth and the stars. Some Baganda had already started following a radio programme on the same but the presenter unfortunately passed on. Some are curious to understand the coloured ring that sometimes appears around the sun and moon, and also if it is safe and affordable to navigate the deep sky. The Bagisu are interested in knowing how celestial objects can float in space despite being very heavy, and also how they maintain a definite path. The Banyoro say it would be a privilege to use equipment and gain scientific explanation. They would like to know if anyone lives up there, or whether there is life elsewhere; the existence and residence of God; the internet and connection with machines to be able to use different communication machines comfortably. The Langi have a big interest to know the operation of the forces of the earth and their impact on humans. Besides, they yearn to understand what causes the movement of the sun and moon, and counting of the days and prediction of the future. All in all, members need scientific explanation that would enhance transition from traditional belief to acceptance of nature. It is hoped that a chance will prevail in which the heavenly bodies will be viewed through simple but modern astronomical tools.

Appearance of celestial objects

The Baganda recognize that stars appear slowly by slowly in the evening as darkness approaches depending on the weather. They think that the stars move because some of them appear seasonally. The Bagisu are cognizant of the fact that there are more stars in the sky during dry season and fewer stars during the rainy season, respectively. Besides, there are periods when one can spot some star patterns. The Banyoro say that the biggest star usually appears near the moon, hence named “friend of the moon” (nyamuhaibona), and that there are periods when there seems to be no stars, presenting apparently clear sky and thought of their whereabouts. In addition, the Banyoro take keen interest in falling or shooting stars (kibonomu), saying that they signify either problem or peace in the near future. Traditionalists among the Banyoro say that there are small stars which appear between 11 pm and mid-night, which guide the fishermen on mid-night entry. The Langi think that the sky normally turns around, making some stars appear and others not. They are aware of the seasonal variation of star patterns, where one sees Orion (Lyer nino) and Pleiades (oyugu) during the time for harvesting simsim (nino), and that dry season (ooro) is characterised by the presence of many stars in the sky, as opposed to rainy season (cwir).

The Baganda think that each of the objects in the sky is unique and has a different purpose, the reason they are called by different names. They recognize that some objects blink and others do not, and there is general variation in size, shape, light intensity, colour, among others. The Bagisu say that some stars resemble, especially those that exist within a cluster. The Banyoro say that stars ordinarily resemble by way of twinkling, but all objects seem to live in different locations, and stand on their own. They notice that the sun is quite hot and appears during day time, and the moon and stars are cool and appear during the night. The Langi consider that most stars appear the same, varying mainly in size, intensity, and colour. The ethnic groups unanimously recognize that stars are not of the same size, with the Baganda and Langi saying that the bigger stars are brighter, and some tiny stars appear as a pool. The Bagisu think that one of the biggest stars is the morning star, and the smaller stars must be very far away. The Banyoro say that the majority of stars are smaller, and that the bigger stars have names.

The moon and its appearance

The ethnic groups recognize interesting pictures on the moon, depending on one’s artist impression. The pictures are mainly figured out when the moon is at its full phase (Figure 2), for which all the light side of the moon is seen. Notably, the picture of a human being is visualized with various impressions. The Baganda mostly see a woman that could be; carrying firewood and a baby, carrying a bucket, or breastfeeding her child, and to a small extent a man with an axe. Others see a yolk of boiled egg, bluish in colour (kisibye egabogabo). In the Baganda tradition, it is said that a woman had collected firewood on a Sunday, and God punished her to go to the moon with her child and a dog. They think the woman is probably Nambi. It is interesting to have encountered a sentiment of this kind:

When I see the new moon, I know Nambi will torment us the women again. As long as you are still young like those daughters of mine, you will have a share of Nambi’s punishment. The men don’t see their menstrual periods...and for us who are old, Nambi knows she has done enough...

The Bagisu also see a woman carrying a baby, but some think of God and Jesus, and art paintings probably map of Africa. The Banyoro say that the picture is mysterious, and some think of a king sitting on a stool, or a woman carrying a baby. Curious Banyoro think that the picture could be black clouds or less illuminated parts of the moon. The Langi notably say that distance makes it so difficult to comprehend the images on the moon, but they think that there is a black woman sitting on the surface of the moon. Traditionalists among the Langi believe that the sun fought with the moon and left scars on it.

The ethnic groups have a wide range of ideas as to why the moon is not seen daily as the sun, saying that it is the plan of the ‘Creator’ that made the moon seasonal. The Baganda say that the moon is irregular, first charging from the sun before it appears, and that the moon usually changes its time of appearance, from early hours of the night to morning hours. So, it appears every night but at different times, hence we may not be able to see it on certain days. Some Baganda think that there is a time set aside for darkness where the moon is obstructed. The Bagisu think that the moon and sun have different roles for humanity, with the moon determining periodic changes during the month, including women menstrual cycle. The Banyoro think that the moon is used for counting days of the month, making it a natural calendar. When the moon first appears - new moon (isongoro), it is considered the first day of the month. In addition, they think that the moon takes long to orbit the earth, that is, more than 24 h. The Langi say that the moon disappears for renaming, and a song was usually sung for this. They take the moon to be a mysterious heavenly body that dies for at least three days in the east and appears in the west, then grows up to maximum size and diminishes again to die, and the trend happens every month. Others think that the moon is sometimes there, but can only be seen under a quiet forest.

The Baganda are amazed that the new moon is very small like a sickle, and grows to become big and reduces again. The moon keeps changing shape and size continuously. The appearance of new moon from the west attracts lots of interest. The Bagisu are concerned with the changing brightness of the moon - from very bright to bloody. They say that when it is raining at night and the moon appears, it stops raining. They also wonder how naturally the moon can obstruct light from the sun during solar eclipse. The Banyoro also take keen interest in the ever changing shape and size of the moon. It is at times very small, with a horn either left or right, and sometimes it behaves like a rainbow with many colours. When the moon is red in colour, an eclipse can easily occur. They say that during the dark moon night, children are warned not to walk about because they could meet bad creatures. The Langi say that when the moon is new and tilts on the right, it is a sign of good harvest, and vice versa. The moon’s appearance is followed by some light rain even if it is dry season, to ‘wash the eye of the moon’ (lwoko wang dwe). When the moon is rising in the east, it is mature and cruel.

The earth and horizon

The ethnic groups agree culturally that the earth is flat, labeling the teaching of science as confusing. The Baganda emphasize that we move on the earth and see it flat, which is what has been known for generations. The Banyoro add that the earth is flat and hilly, with the Langi saying that the earth is flat with an edge where the sun falls at sunset. The Langi tribe also considers the directions; East (Tung-kide), West (Tung-too), North (Tung-anyaradii), and South (Tung-anyaralum) are mysterious constructs. Most members of the ethnic groups understand that the sky appears to touch the earth due to eye sight limitation to distance. They say that the horizon is the point where our eye sight ends. Some Baganda think that the sky is curved like a hut, which makes it bend to touch the ground, while others think of an imagination because one never gets there in an attempt to walk towards the horizon. The Bagisu think that the eye is usually deceived by distance. The Banyoro think that the earth and sky are not meant to touch each other naturally, and say that as you move towards the point where they seem to meet, it will move also, but the earth continues to look flat. The Langi think that where the two seem to meet is the end of the earth, where the sun falls on the western side and emerges on the eastern side. They also believe that the sky is round, with a diameter equal to the length of the earth.

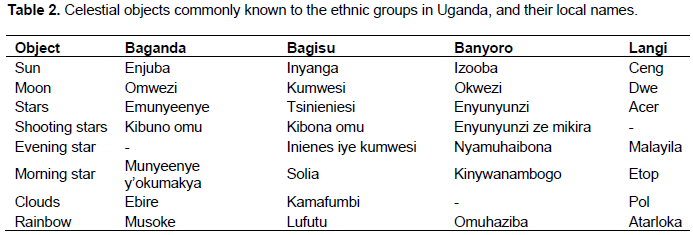

Naming of celestial objects

Common celestial objects known to the ethnic groups are; the sun, moon and stars. These are called using names that show similarity of purpose. Table 2 shows a sample of local names of familiar astronomical objects. These objects have been known from stories by parents and elders, and sky watching. To some extent, some have read about them from newspapers and religious books, as well as studying subjects like geography and physics. The appearance and functionalities of celestial objects have impacted their naming. To the Baganda, the sun is named enjuba because of its brightness, the moon - omwezi because it appears every month, and the stars - emunyeenye because they appear twinkling in the sky. Then, shootings stars are called kibuno omu because they are fast moving, and each of them can only be seen by one person and it disappears. In addition, the Baganda also have sengendo for planets.

For the Bagisu, the sun (inyanga) implies brightness or hotness (lianga) during day, kumwesi (moon) takes one month before reappearing, and tsinieniesi (stars) are heavenly bodies that twinkle or glitter in the sky, that is, the stars have sparkling lights. The Banyoro too have izooba (sun) because it keeps on coming (eyezooba) daily with its light, and it is similar to the yolk of an egg. It is believed to be the god that formed everything (kazooba nyamuhanga), and has the highest brightness of light. The origin of okwezi (moon) is okweza, meaning high yield, harvest, and even human production. The moon is seen as a kind of god because everything has a source in it, and it gives out plane cool light during the night. It is still considered so among Muslims, with its image put at the mosques. The moon appears 13 times a year, giving 28 days for an average month. Enyunyunzi (stars) are called so because they twinkle or glitter in the sky. In conjunction with clouds, stars look like flowers which decorate the sky, and some form interesting pictures. The Langi have similar naming too; the sun (ceng) gives light during the day, moon (dwe) comes on a monthly basis, and stars (acer) glitter or have sparkling lights. Women prepare for their monthly cycle upon citing the new moon.

Some Baganda are able to recognize some star patterns and bright stars. For example, morning star (alitagiri or munyeenye y’okumakya), Pleiades (nakakaaga), which form a pattern of Chrismas tree, and three clustered stars (nakasatwe). Most Bagisu do not recognize star patterns, but are aware of bright stars and their colours, notably the morning star (solia). The Banyoro recognize mainly shooting stars (enyunyunzi ze mikira) which are associated with bad occurrences, Pleiades (ekikaaga), stagnant stars in the east and west, three aligned stars in Orion, and a bright star that comes along with the moon (engazi yo omwezi). Star patterns commonly known to the Langi are: Orion (lyer nino), which is a symbol of simsim harvest from the lining of the three stars (Orion belt) equated to poles used for drying simsim; Pleiades (oyugu or acer abicel) with many stars but only about six are seen in turns, and sometimes shooting stars emerge from it. They also recognize the Milky Way (apoki piny) which they think divides the sky such that dry season is represented on one side, and wet season on the other side.

To the Baganda, the evening star is thought to be near the moon. It is usually the first and brightest star to appear in the sky, and brings relief when there is no moon. The morning star (munyeenye y’okumakya), also named Stella Maris, portrays peace in a new day, and it is the last brightest star just at dawn. For the Bagisu, the morning star indicates day break, the time to prepare for prayers, and the evening star is recognized when the moon is about to appear. The Banyoro call the morning star kinywanambogo, which marks the end of the night and the beginning of day time. It is also seen as the friend of buffaloes, appearing usually at dawn in the east. The evening star (nyamuhaibona), also called the friend of the moon, always appears in the west. It marks the end of day time and the beginning of the night. The Langi call the morning star etop, believed to guide the sun to rise to mark the end of the night, and the evening star malayila because of its enormous brightness, or cwar dwe (husband of the moon) because the new moon normally appears close to it and gets persuaded.

Celestial objects and weather changes

Among the ethnic groups, weather changes can also be predicted by observing the moon and stars. The changes in appearance of the heavenly objects can show that it is going to rain or not. Usually, when stars are very many in the sky, it is dry season, otherwise rainy season. The Baganda expect sunshine when the moon is bright red in colour. The Bagisu say that the new moon comes with rain as a blessing from the Creator. The rain is said to wash the new moon. At full moon, less or no rain is expected. For the Banyoro, when the new or full moon is too bright, rains and plenty of food are expected, that is, good harvest. This is also true when the stars are too bright. In contrary, when the moon is not clear, people expect sunshine, so never waste seeds. The Langi present a number of considerations, including the positioning and colour of the moon, as well as the Milky Way. Too many stars with cold mornings and evenings would imply dry spell, yet fewer stars and cloudy sky signal rainfall. The new moon always comes with rain to wash the face of ‘baby moon’ (atin dwe), but a reddish moon would show that there is going to be sunshine for some time.

Observation of celestial objects and interpretation of weather patterns are taught mainly by parents and elders in the community, and everything begins from childhood. To some extent, self-viewing, reading, and personal experiences also play a key role in understanding celestial objects. In Buganda, most of the information is passed during time for eating in the evening. The Banyoro also have story tellers and information from their Palace, and most of the information passed at the fire place. The Langi start passing information as soon as the child begins to talk and this continues through to the time when someone is able to graze animals.

NATURE AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC ACTIVITIES

Celestial Objects in Agriculture

As in weather prediction, the moon’s appearance and number of stars can enable someone decide to plant or clear the garden. With a reddish moon and too many stars, sunshine is going to be too much to plant any seeds, but is good time for harvesting and drying of crops. With fewer stars and bright moon, the rains will be in plenty for crop production. Farmers among the Baganda and Bagisu, to some extent, use the bright full moon to wake up early and dig at dawn. They usually plant just at the end of dry season when there is suitable warmth for germination and subsequent downpour for moisture. The Banyoro do follow weather changes brought by the moon. By seeing trees shade off their leaves and regenerate, grass and rains, the farmer should start sowing. The position of the moon indicates an activity to be done. For example, the moon on the 15th day, planting for the first rain, with sufficient warmth for seeds to germinate and grow. For the Langi, the bright moon also helps people wake up early for digging, with birds singing and rejoicing as well. Fewer stars and unclear moon signal plenty of rainfall which the farmer utilizes for planting. And when the stars are too many in the sky, it is dry season. The farmer does harvesting and drying of crops, as well as planning for the next rainy season.

Celestial objects in fishing

This cuts across the ethnic groups. When the moon is too bright and just about full, fishermen rarely cast their nets because they can hardly catch fish. This is even worse with the moon shining directly overhead, because the net and fishermen are visible to the fish. Therefore, it is mainly during new or dark moon that more fish can be caught, and according to the Banyoro, the growth of the moon within the month leads to decreasing fish harvest. However, other fishing methods work well with a bright moon. For example, those who use hooks and baits can extend their fishing time to night hours, as the fish will be able to see the bait and go for it. The Bagisu say Dagaa fish usually come near the water surface when there is moon light, so can be collected using fish baskets. The Langi also reveal that the moon and stars also help fishermen to determine direction of the wind in order to minimize accidents in water.

Celestial objects in hunting

The ethnic groups say that some animals do move at night, so can be trapped and caught using moonlight. At new moon when some rains come, hunters can easily sight animal foot marks, so can lay their traps or nets. During the dry season, animals usually hide from the heat, but come out in large numbers with rainy season, as the moon and grass appear, so they can be trapped. The Baganda believe that the small god (ddungu) uses the moon and star lights to hunt in the night. The Bagisu say that it is difficult to collect white ants when the moon is bright because the moon will provide a wide alternative lighting system, but antelopes usually graze with clear moon light, so can be captured with nets. For the Banyoro, buffaloes enjoy eating with new moon and morning star, so hunters can trap them. Also, catching grasshoppers, white ants, as well as picking mushrooms, are all done with dark or new moon. The Langi consider that hunting is almost done throughout all seasons, but it is difficult when there is too much rain and the grass has grown tall. So, little rain is desired to spot animal foot marks.

Celestial objects in traditional and spiritual rituals

Muslim members of the ethnic groups follow the moon to determine holy months, especially the month of Ramadhan (9th month of Islamic calendar) to enable them fast. Fasting normally begins on sighting of the new moon and continues until the next new moon is seen. The Islamic religion as a whole uses the new moon and stars as symbols. The morning star indicates day break, hence preparation for early morning prayer. Christians on the other hand use stars to remember the joy of Christmas because it is said that a star directed the shepherds to the place where Jesus Christ was born. Thus, star signs are used to proclaim good news. Overnight prayers are quite good with bright moon light and clear sky. In Buganda, the new moon triggers night dancers’ operation, and traditional healers as well use the brightness of the moon. Also, women prepare for their monthly periods. For the Bagisu, night dancers also use the dim moon light, usually with the appearance of the new moon. At half-moon, wild animals give birth and most women have their menstrual periods. It is also believed that this is the time for movement of the spirits of the dead. People usually gather around to worship as the god of the moon shall be watching over them directly at night. For the Banyoro, ancestors performed sacrifices during the new moon (okubembeka), presenting everything at the traditional altars, hence prayers, eating, singing and dancing are done, similar to Christian practices. At the new moon, lots of sacrificial ceremonies (ebibali) take place at the altars. Regalia holders appear and prepare the king (omugabe) to sit on his throne, and perform functions at the embareko. The king would visit the kraal in the palace and cultural rituals are performed. Also, most kids are known to develop new teeth, and there is dancing of the twins, and some traditional faiths are effective upon citing the new moon. Men and women usually assemble at sites to perform cultural rituals, which are also done for fishermen and hunters. Treatments for various sicknesses are done following the changes of the moon. For the Langi, things are gradually fading, but also done according to the appearance of the moon, mostly faint moon (new or dying moon). Depth of epilepsy disease and treatment and rebuking of associated spirits can be done. Such is the period when the deaf and eunuchs can gain strength to some extent. At new moon time (young moon in the west), children are told not to go outside their house for fear of getting infused from rituals, which are mainly done around such times. Rain makers would study the moon and stars, and in case there was drought, they would assemble under a big tree (kworo) to dance the rains (myelo kot). Newly born children are not allowed to view the moon, until the first time when they are shown the moon with a pasting stick (lut’ogwec) three or four times, for boys and girls, respectively. Similarly, when it drizzles, the child is given rain drops three or four times depending on the sex, to prevent some small swellings and burns on the child’s body.

Before the coming of religion and technology, the ancestors attached entirely everything to gods, namely; the gods of the sun, moon, rain, and so forth. Such gods were created depending on the usefulness of the celestial bodies, and were responsible for their appearances. For the Baganda, the god of the clouds or sky (kibuuka) used to rise up during wars. He was never stopped by arrows, and was always a successful warrior. The god of rain (mukasa) was invoked whenever there was drought. The god of hunting was called ddungu, and rainbow (musoke) was related to the god of water. For most women in Buganda, whenever you see the moon over you, it means you are pregnant lest you fall sick. For the Bagisu, the god of the sun was associated with blessings, and the moon was considered a god because of its characteristic appearance and disappearance. There is very scanty information about them nowadays. For the Banyoro, the sun, moon and stars are symbols of gods. The sun is believed to be a miraculous god (kazooba nyamuhanga), and the strongest god since it also appears to be the strongest of the heavenly bodies. He is worshiped and its hotness means that if you do wrong, you will be burnt.

Witch doctors use water and glittering sun to perform their things. Also, women perform rituals near the fire to associate with the sun. The morning god is associated with the morning star (kazooba omuchezi), and is related to the sun. The Langi religiously believe in Jok’amalo (God in the sky), and consider every happening on the earth to have connections with events in the sky. The Jok’amalo is believed to be the only one God, the Creator and source of everything.

Events associated with the appearance of celestial objects

In Buganda, fasting for Muslims is associated with the appearance of the moon. When the rainbow (musoke) appears, people pray or ask for what they want. For the Bagisu, bent or tilted moon is a sign of war; shooting stars are associated with a prominent person dying if he or she is in a critical condition; when dry season becomes foggy, then there will be worms and dust shall be lifting eggs from one place to another since they will be light; an orange colour of the sun means dry season is coming to an end, and rainy season will follow so farmers can start planting. For the Banyoro, the moon’s appearance is a sign of drought or rain, as well as diseases. Naming of children depends on the appearance of stars. Certain times you do not have to cross a river or pass a forest, neither do you fetch water at midnight nor midday. For the Langi, harvesting and celebrations are mostly done during the dry seasons when stars are many and the sky is bright; a ring around the moon is believed to be indicative of the death of an important person; sunset implies night time is approaching, and morning star brings forth day time; too much wind is a sign of drought and famine; and very bright sky and hot weather, one expects pest and diseases.

Perceptions of the rainbow

All cultural beliefs align with religious beliefs. Therefore, the rainbow is a sign of God’s fulfillment of his promise never to again destroy humanity with water or rain. Hence, the rainbow is seen as a blessing. To the Baganda, the rainbow signified a spirit drawing water, so no rainfall is to be experienced. It, however, shows God’s anger towards his people, but because of his mercy, he sends the rainbow (musoke) to suck out the rain and avoid floods. Hence, the otherwise bad rain is absolved by the rainbow. To the Bagisu, the rainbow stops rain when it is coming. It can suck blood from a person who attempts to cross it, or those who may be found fetching water. The rainbow is also a sign of God’s displeasure with humanity, but he has forgiven them. There was likely to be a heavy downpour, but prevented. So, people should glorify and worship the Creator. For the Banyoro, the rainbow is the sign to prevent more rains. It appears opposite to the direction of the sun, and no serious rains would come. When the rainbow stands on your side, do not attempt to cross it because it can suck your blood. A well and palm tree are found where the rainbow is formed, the site of which is used to perform rituals. When there is little rain falling and sunshine, it is believed that a leopard has delivered. For the Langi, it is believed that when a rainbow appears, it is not going to rain at that moment. The rainbow usually plants its ends in two swamps (wells). It is believed that lightning has delivered children in the ant hills near the swamps, and it has come with frightening colours to pick them. When you hear the sound of lightning, then it has picked the children believed to be like clocks. It is also at the swamps that lightning camps, in case someone has sworn by its name. In such cases, someone should take a calabash with ashes, and sow the ashes continuously in the direction of the rainbow until it disappears. Anything hit by lightning is not eaten by any ordinary person but itogo who is able to rebuke the lightning. When lightning strikes someone or something near a home, a special tree (iburka) is planted at that spot to prevent any future occurrences.

Wonders and myths

Across the cultural board, the introduction of religion, education and technology has somehow influenced the traditional view point of the celestial objects. Homilies by priests and knowledge of science demystify traditional beliefs and practices. The work of the astronomers has revealed that the sky is vast and contains other planets that could support life. It is wonderful that technology has made the moon reachable. It has also come to be known that some moving stars are actually satellites, and that God has created everything including the sun that supports life on earth. Flights have also enabled some people to see the curvature of the earth. However, the majority of the traditionalists still hold their perspectives of heavenly bodies.

The night sky

The Baganda say that the night sky is a wonderful God’s creation. Many things to ponder include eclipse, shooting stars, God’s arrangement of the celestial bodies, and earthquakes. The moon normally starts from the west and dies in the east, contrary to the rising and setting of the sun. As a myth, the full moon signifies a dangerous night, and the night sky is good for someone who is swallowing. The Bagisu say that stars are guides for people fishing on big lakes to determine direction, and think of the sky as God’s dwelling place. Shooting stars are only seen by one person at a time, as falling from the sky. If two people see them at the same time, then they will die on the same day. For the Banyoro, the eclipse of the sun takes place during the day, but it is dark again. Many Baganda and Banyoro wonder because shooting stars are only seen by one person at a time (kibonomu), noting that they are very bright and so fast that you can’t move in the house to ask someone to come and see them. They are seen as blessings (okubonekerwa), and some Muslims sleep outside to see the miracle and be blessed. The Langi are amazed at the highly ordered star patterns and no collisions of celestial objects even when there are movements. One wonders how the Creator made the earth and the objects in the sky, and whether there will be an end or not, and why drought comes when there are too many stars, and vice versa.

Movements of celestial objects

Majority members of the ethnic groups are aware the earth’s rotation causes the apparent movements of celestial objects across the sky, noting that as the earth we stay on rotates, we pass these objects and contrary to our movement, we see them moving. The Baganda think that it is God’s arrangement that objects are seen to move in the sky. Some have been taught that the objects in the sky do not move, only the earth moves. So, it is thought that the earth moves around the stars. Others think that heavenly bodies are in constant motion. The Bagisu say that some of the celestial objects don’t appear to be moving but move naturally. The Banyoro say that people do not think much about movement of celestial objects, instead they are interested in their position and time of appearance. People usually know the movement by changes in position of shadows of some prominent trees. The traditionalists believe that God commanded celestial objects to move, a culture which must be maintained. The movement is puzzling, only God knows where they change positions, and seasonal changes. The Langi think that the movement of clouds causes the movements of other heavenly bodies. Culturally, the earth is fixed, and the objects in the sky must be moving. They are believed to be alive, so they must characteristically move. Others think that it is the sky that rotates due to God’s power, so God moves the objects, and they are in motion with respect to the stable moon.

Time for the celestial objects

The Baganda and other ethnic groups believe religiously that it is the plan of the Creator that stars appear during the night, and the sun during the day. God gave the sun and moon authority, the sun being king of the day and moon king of the night. But most members are enlightened and know that the sun’s light overpowers the stars, but they are also there during the day. Some members think that stars hide or sleep in the clouds and sky. The Banyoro think that stars have dim lights, but according to nature, they are ever there, whether raining or shining. As a confirmation, the morning and evening stars are clearly visible with decreasing sunlight intensity. Because of enormous distance, light from the stars can only be supported by darkness. The Langi say that the stars are far high up behind the blue sky, so can’t be seen with the bright sun light that overpowers them. But under a forest, it is possible to see stars in a clear sky.

Most members are also enlightened and applaud the earth’s rotation for the daily movement of the sun. During night time, the sun is on the other side of the earth, thus part of the earth can be in the light and another in darkness. The Baganda say that at sunset, the sun goes down to give light to other countries, so the sun does not hide. Some think that the sun falls in a hole, and goes down to sleep and rises early morning in the east. Others say that it is God’s arrangement that the sun appears during the day and stars at night. The Bagisu also say that the sun does not hide, except the dark side of the earth shall have turned away from the sun. Some Banyoro, however, wonder and think that the sun hides in the clouds, or falls down and dies in the evening, then rises in the morning. Others say that the sun stays in its resting place according to the command of God, not to give light during the night, and the shape of the world, flat and hilly, hides the sun. However, when you follow the sun, you will continue seeing it. The Langi similarly believe that the sun falls down at sunset, and it is a bad omen for somebody to meet the sun going back to the east during night time. Thus, the sun sets and plans to go back where it rises in the east, giving us another difficult time of the day.

The sun is thought to be different from stars. The Baganda say that the sun is the sun and stars are stars full stop. It is another body of its own, huge, round and very hot. The sun appears during the day and stars during the night. Very few think that the sun could be a big burning star so near to the earth, hence its enormous brightness and hotness. Likewise, some Bagisu think that the sun is a very big and hot star, because it also twinkles. The Banyoro think that the sun could be something different, not quite known. Just like the Baganda, they say that the sun is sun, stars are stars, and moon is moon. But being single, the sun is like a star but disappears soon. So, the sun is a body on its own and is quite massive. The Langi also say that the sun is culturally different, because if it were a star, we would see it at night. It is said to be a big object with too much heat that extends to the earth. During dry seasons, it is hot and people believed that the sun has moved closure to the earth.

The eclipses

The Baganda say that, for the sun and moon to meet, they will fight to be in one position, a coincidence which is quite rare. It can create half day and half night, which is quite a scaring moment that people are advised to keep indoors. It is said that the moon normally wins. For the Bagisu, if the sun and moon meet, something will happen which we cannot tell now. Some say another sign of God’s annoyance, which can lead to the end of the world or universe. The Banyoro think that the sun and moon meet in a fight called eclipse (izooba likulwana no mwezi). Some think that the world may come to an end, so people are advised not to be moving because darkness can get them where they do not desire. A story is told among the Banyoro that a king went to war in Ankole, a neighbouring region of the Banyankole, in which two eclipses occurred and the king lost one of the wars.

Therefore, eclipse of the sun is associated with bad luck or change in leadership. Some people think that the fighting of the sun and moon is according to God’s power, to show human beings that God can perform miracles. The sun wins during the day, and vice versa, because of God’s authority. It even means that when human beings die, they can meet. The Langi think that when the sun and the moon meet, it is a sign of problem because it causes coldness and darkness of the day. They say that the sun moves to the west and moon moves to the east, so they can meet and should be a systematic event which occurs in a given period of time.

The night darkness

The Baganda say that being outside the house at night depends on someone’s ways of life, reasons and environment, but not for security purposes because dangerous people and animals abuse the night to do mischief. Besides, strange and weird things happen at night, including night dancers at the appearance of new moon. The night’s coldness is said to be unfriendly to humans. However, night time is good for personal viewing and mastery of the sky. The Bagisu say that planets and stars are not harmful, except some people take advantage of darkness to do mischief. The Banyoro say that wrong doers move at night, and also there are wild animals that can attack. In addition, the visibility at night is poor, so it is difficult to tell what might happen, and bad spirits (ibigasaigasa) also move at night, so can befall those loitering in darkness. They say that if unavoidable, there should be clear moon light, or someone should use a torch and fire. The Langi fear someone may meet the sun returning back to the east, a situation that will lead to illness, unless a ritual is performed. During dry season, only elders would stay outside to study the weather patterns; otherwise, darkness is for sleeping and resting; security is required because many bad things happen at night, which include movement of wild animals and performance of rituals.

Formation of celestial objects

The Baganda say that the stars and moon were created by God at the beginning of the world, although others say that the visible heavenly bodies are the spirits of the ancestors. The Bagisu, Banyoro and Langi also agree to the notion that heavenly bodies are God’s creation, that is, the existence of stars, moon and other objects resulted from God’s order. The Banyoro think that God the Sun (Kazooba Nyamuhanga) created the stars and moon. Traditionally, there is a Creator for all things in heaven and on earth. The Langi say that a person with a big hand created them and placed them in their rightful positions with instructions. They believe that objects obey the Creator, hence the natural order. One senior member said:

Children, if God had no hand in these things, the world would be in chaos...coronavirus would be like nothing...many heavy objects would be falling every now and then! Would anyone be able to exist? God is alive, even if some of you are unbelievers.

If the celestial objects suddenly disappeared, it would leave a lot to be desired. The Baganda say that it would be the end of humanity and living things. There would be total darkness and unbearable environment; everything would collapse, and day and night become indistinguishable. It would be a nasty experience and disaster over the whole world, and even criminals may find it difficult to operate. The Bagisu also think that the world would be very dark and problematic to people and animals and they will die. It is what everyone wonders, but everything would freeze, no warmth and light to support growth, and life would gradually come to an end. To the Banyoro, there would be total confusion, desperation, and end of the world. It would be a day of hell, and everything destroyed. The king would lose his throne, and there would be total panic. They also think that even if the sun and moon were to change their course, that is, the sun starts from west and moon from east, that would be a disaster. The Langi think of a big calamity that would strike the whole world, an indication of the end of the world. And there wouldn’t be things like today, yesterday and tomorrow, and perhaps the Lord would come and people disappear.

Other concerns

The Baganda say that the sky is God’s creation and the characteristics of its objects should be preserved. It hides heaven where man’s soul will live forever, and underworld is the home for the evil spirits where Walumbe stays. Another sentiment came in here:

By the way...For us in Buganda, Nambi and Walumbe are a problem...Walumbe is the cause of death. He wants everyone to be with him in the underworld. It must be a hard life there. To be with Kintu up is much better.

They add that on judgment day, everything will be at the same level. The government should help establish sites where the local population can access instruments to navigate the sky. People believe that musoke regulates the amount of rain water by sucking from the clouds and pouring into the lakes or rivers. Most traditional sacrifices are done during the time of the new moon (masumi), and one also wonders why clouds change colours.

The Banyoro believe that there is blessing from the sky because rain comes from there. The sky is synonymous to heaven and is God’s dwelling place. On the other hand, the inhabitants of the underworld are ghosts. Clouds are shades that cover us from the sun’s heat. Stars and moon are beautiful and believed to be symbols of excellence that are controlled by God. Many people are excited at the new moon, and the moon cycle is counted by tying knots, which help in planning activities including taking cows for mating. The new moon in general signifies production, and women are told that they can predict the period they are able to conceive from the time the new moon appears. Such a period is characterized by limited or no rainfall. The moon appears thirteen times in a year, hence the number of times a woman sees her periods. There is a black insect that glitters at night like stars. Such insects were quite many during the dark periods of the moon. Parents discourage children from touching these insects in fear of cancer.

In Lango, when lightning strikes someone dead, burial takes place near a swamp, contrary to which lightning will disturb. Immediately an eclipse occurs, or a unique sign is seen, elders usually assemble under a tree at around one O’clock to fast, pray and apiece God for people’s sins. In 1820, a meteorite is said to have fallen in Langi closed to Ngetta, Obim and Erute, splitting the people who had settled there. Ngetta Hill took up the name for the split, but itself was not the meteorite. Traditionally, people used to focus the weather and trends of events for the year accurately, but this has been affected by western influence and religion. Some enlightened members say that it is important to strengthen traditional view point with scientific truth, which must be explained to the local people. The Langi interpretation of the simultaneous occurrence of sunshine and a drizzle is that a hyena is giving birth near a kraal at that very moment. It is thought that the earth is the biggest planet, and life after it will be in heaven. Most people lack knowledge of the heavenly things, which is perhaps attainable with very high level of education. There are many visible flying objects, the mechanisms of which leave a lot to be desired.

For the first time, it has been possible to obtain primary information on cultural astronomy in Uganda from four ethnic groups. There are many aspects in which the cultures treat particular celestial objects in a similar way. The four ethnic groups have attachments to a few of these objects, some of which are myths that need to be unlearned through scientific means. It has been found out that only a few stellar constellations are known to most Ugandans. There is need to find out what other ethnic groups in Uganda have to say, something that should constitute the second paper. Since the sky is a natural laboratory, astronomy outreach programmes are recommended in Uganda, in which the population will have access to view celestial objects through a telescope and acquire scientific explanation of what people see from time to time. This will strengthen the teaching of science and modern astronomy at schools and universities.

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

The study was granted and facilitated by the Government of the Republic of Uganda under the Makerere University Research and Innovations Fund. The authors also thank the cultural and political leaders for granting permission during data collection.

REFERENCES

|

Amone C (2015). Ethnicity and Political Stability in Uganda. Ethnopolitics Papers 32:1-18.

|

|

|

|

Campion N (1997). Editorial. Culture and Cosmos 1(1):1.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chapman S, Catala L, Mauduit JC, Govender K, Louw-Potgieter J (2015). Monitoring and evaluating astronomy outreach programmes: Challenges and solutions. South African Journal of Science 111(5/6):1-9.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Classic Africa Safaris (2020). Uganda: Statistics, Facts, History & Security. URL:

View

|

|

|

|

|

ESA (2001). Science & Exploration: View of the Moon seen Apollo 17. URL:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Ghosh I (2019). Every Visible Star in the Night Sky, in One Map. Accessed on May 13, 2020. URL:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Government of Uganda (2005). Constitution amendment (no. 2) act, 2005.

|

|

|

|

|

Holbrook JC (2007). African Cultural Astronomy - Current Activities. African Skies 11.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Karttunen H, Kröger P, Oja H, Poutanen M, Donner KJ (2017). Fundamental Astronomy, Springer-Verlag, Helsinki, Finland.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kasujja JP, Mugagga AM, Bakaluba MT (2014). Ethnicity and the Formation of the East African Political Federation: The Case of Uganda, International Journal of Innovative Social Sciences and Humanities Research 2(2):42-55.

|

|

|

|

|

Koontz LL (2002). Your guide to the constellations: Instructor's handbook.

|

|

|

|

|

Ricart-Huguet J, Green E (2018). Taking it personally: the effect of ethnic attachment on preferences for regionalism. Studies in Comparative International Development 53(1):67-89.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sasso Uganda Safaris (2020). The People, Settlements and Tribes in Uganda. URL:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Sejjaaka SK (2004). A Political and Economic History of Uganda, 1962-2002, pp. 98-110.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) (2006). 2002 UGANDA POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS, Uganda Bureau of Statistics, Kampala, Uganda.

|

|

|

|

|

Urama JO, Holbrook JC (2009). The African Cultural Astronomy Project, Proceedings of the IAU 260:48-53.

Crossref

|

|