ABSTRACT

Nigerian law libraries, despite the intervention of Council of Legal education, are still not endowed with every resource needed to satisfy information needs of diverse users. This is coupled with the fact that Nigerian universities are still struggling to manage insufficient funds normally received from government. Resource sharing as a means through which organisations interchange and share their meagre resources for the good of many is supposed to be a way out for Nigerian law libraries who would have to prepare their students and members of legal profession for their law program, mock and moot trials, clinical legal education or other practical education. However, it has not been documented that there is an organised resource sharing practise carried out in Nigeria among law libraries. The study investigated the practicality of resource sharing among academic law libraries bearing in mind the immense benefit it provides to education and learning. Survey research design was adopted for the study. The population consisted of 19 law librarians from Universities that attended 2017 law librarians’ conference in Nigerian Law School Abuja. Questionnaire was used to collect data. Due to the small population of law librarians, all the population was used for the survey; only 14 questionnaires were returned. Mean and standard deviation were used with a likert point scale to determine positive (2.50 and above) and negative (2.49 and below). Research questions were analysed using frequency count, percentage, mean and standard deviation. The results revealed that there was no formal practice of resource sharing among the participating law libraries. Law librarians informally share their knowledge on personal basis with their colleagues. Law libraries are supported financially by University Libraries and other organisations; and law librarians that participated understand resource sharing despite the fact that it is not practised by their libraries. There is also no written policy on resource sharing among the libraries that participated in the survey. The study concluded that there is no application of resource sharing among academic law libraries in Nigeria. The study recommended that Council of Legal Education as the overseeing body in legal education should initiate resource sharing practice among academic law libraries as this would provide ease of access to vast academic resource and ensure constant skills development among law librarians in Nigeria.

Key words: Resource sharing, law libraries, collaboration, communities of practice, legal education.

Information sharing has always been a veritable way to interrelate, collaborate and develop. In an academic environment where learning takes place, sharing of resources becomes a way of satisfying the academic needs of the campus community and also a way out for libraries that do not have enough funds for resource acquisition. Resource sharing then becomes a term which signifies that libraries have come together to reach an agreement on how to collaborate and exchange materials useful for their users. This understanding is not only shown through their policy but also through the sharing of their bibliographic contents for awareness and accessibility. Although partners sharing resources can interrelate and access one another’s resources, however such sharing must be based on a policy that dictates their actions (Owolabi et al., 2011).

There has always been a practise of professional assistance where young lawyers visit endowed law offices to use their materials, borrow their materials and seek clarifications on areas of law (Thompson, 2007). This practise has been accepted as a norm with no policy attached to it; the old raising the young who always look up to them for resource assistance. This scenario in legal practise seems to have transcended to law libraries in Nigeria, as students and researchers could visit any other organisation and academic law libraries to source research information; as far as he or she is able to identify him or herself formally, access to such materials would be given (Gross Archive, 2018). This has become an assumed relationship that has not been questioned but which has not been made formal. Thus, as much as academic law libraries are cooperating, they can as well decide not to cooperate without been challenged. This is not resource sharing in the context of this paper but mere professional interrelationships that has been accepted as a norm; a relationship as seen in academic law libraries in Nigeria.

Academic law libraries right from inception has always been linked to law profession and practice (Ali et al., 2010). Its presence always presents the idea that a law program is been run or that a law practise is been carried out. This is because law libraries provides human and materials resources needed to carry out the teaching and practise of law (Boston University School of Law, 2018). It is basically because of this that accreditation councils and academic stakeholders in Nigerian legal education mandate institution desiring to run law program to have a functional law library pursuant to issuance of licence for law program (Nwofor and Ilorah, 2015). The essence of this insistence that law libraries be established before issuance of licence for law program is because of the need to have resources that would provide foundation for teaching and learning. However the establishment of law libraries and law programs coupled with provision of academic resources have not been adequate to maintain legal programs as Nigerian accreditation teams keep expecting current provisions and new developments that are in line with academic trend. This has posed a problem among the legal academia as there has not been much financial support for academic law libraries; except during accreditations (Komolafe-Opadeji, 2011). Thus materials purchased during law accreditations are assumed to provide support till the next accreditation period when university management would release finance for updating of resources. This becomes a poor academic practise that is not helpful to users who need current resources to stay updated; especially when academic materials keep getting updated. The fact that there is need for continuous update of academic resources in the face of meagre financial support is supposed to provide a leeway for resource collaboration in order to provide better services. Six years have gone since after Ogba (2014) study on law libraries and resource sharing and there is a need to find out the state of academic law libraries and their ability to share their resources among themselves. Could it still not be practical even after six years? Could Nigerian academic law libraries, still not be able to come together to collaborate towards resource sharing goals? And could there have been changes after the first study carried out by Ogba (2014). These are issues leading to the statement of problem in this study.

Statement of the problem

Nigerian law libraries, despite the intervention of Council of Legal education, are still not endowed with every resource needed to satisfy information needs of diverse users. This is coupled with the fact that Nigerian universities are still struggling to manage insufficient funds normally received from government. Resource sharing as a means through which organisations interchange and share their insufficient resources for the good of many is supposed to be a way out for Nigerian academic law libraries that would have to prepare their students and members of the legal profession for their law program, mock and moot trials, clinical legal education and other practical education. However, it has not been documented that there is an organised resource sharing practise carried out in Nigeria, among academic law libraries. It is ideally in the light of this that this study is carried out to determine the application of resource sharing among law libraries in Nigerian Universities.

Objective of the study

The main objective of this study was to find out the practicability of resource sharing among academic law libraries in Nigeria. The specific objectives are to:

(1) find out the culture of sharing resources among academic law libraries in Nigeria;

(2) investigate the financial help given to law libraries as support to resource sharing in Nigeria;

(3) find out the written policy supporting resource sharing among Law Libraries in Nigeria and

(4) Determine if law librarians understand resource sharing practice.

Research questions

The questions which this study sought to answer were:

(1) What is the culture of resources sharing among law libraries in Nigeria?

(2) What is the financial help given to support resource sharing among academic law libraries in Nigeria?

(3) What is the written policy provided to support resource sharing among law libraries in Nigeria?

(4) How do academic law librarians understand requirements for resource sharing in Nigeria?

Resource sharing is the act of formally collaborating with like organisations and agreeing to harness their resources towards a common goal. In line with this, organisations involved in resource sharing create a common development policy, agree on what to develop in their collections, how and when to develop their collections; thus they come together and harness ideas to create ideal collection development for their common benefits. Ali et al. (2010) assert that resource sharing is a new form of collection development that has overtaken ownership and access. Thus there is no sole ownership and access to resources anymore, but a sharing culture that provides room for unlimited access to wide range of resources; it is therefore one of the best practises on collection development and information services. Although resource sharing seems to be a best practise developed newly, however it was initiated in Nigeria more than a decade ago (Abubarka, 2007). All the participating libraries were directed to send copies of their catalogue cards to National Library of Nigeria; later on interlibrary loan of materials began and was monitored by a committee set up for resource sharing purpose. However, a practise that was initiated more than a decade seems not to have developed into a norm as law libraries studied in Ogba (2014) were shown not to be practising resource sharing services. Although one could say that resource sharing was pragmatic at its beginning because of the attention given to it through setting up of a monitoring committee that mandated libraries to send copies of their catalogue cards to National Library of Nigeria. Thus, making it a non-voluntary action which is not within the description of resource sharing; the ideal resources sharing as portrayed in this paper is one where libraries who have deficiencies and strengths decide to take advantage of their strengths as an exchange to another organisation in order to cover their deficiencies. Although it could be asserted that there is need for the intervention of the Council of Legal Education, Nigeria, to mandate academic law libraries to collaborate; however it should be known that what belongs to one cannot be mandated to be shared with another; it will be an abuse of property right (Archian, 2020). Thus resource sharing activity has to be voluntary for it to be effective.

Owolabi et al. (2011) asserted that admittance, book donation and gifts were forms of resource sharing practises in Nigeria but these are merely practises carried out to assist researchers who identify themselves as students of an institution; while book donations cannot be resource sharing since sharing has to be premeditated and based on mutual agreement to cover deficiencies of the parties involved. Thus parties practising resource sharing must have written agreement stating their goal, date of initiation, type of resources they intend to share, their limits, mode of operation and mode of termination (Sec.gov, 2009; Thompson, 2007). By this, it could be asserted that there has not been any form of resource sharing practice among academic law libraries in Nigeria.

According to Ogba (2014), the rationale behind non practise of resources sharing among the libraries studied was found to be apathy towards needs, change and development; although earlier studies in Nigeria portray that lack of adequate financial sponsorship could be responsible (Komolafe-Opadeji, 2011). However actions are transient and development is recurrent, therefore situations that were earlier found to affect resource sharing could change for the better as Rayner and Walsby (2012) assert that modern libraries have shifted from applying best practise to innovative practises that meets their users’ needs. Thus libraries dictate what becomes best practise in line with the needs found in their environment; while they use their available resources to solve those needs. This means that finance as asserted by Komolafe-Opadeji (2011) would not be contributing much to inability to share resources. It could then be said that Nigerian academic law libraries could indulge in resource sharing practice in order to meet up with the modern demands of users of the 21st century who have a knack for digital technology. This is because resource sharing practise is more feasible with ICT (information and communication technology) and users who are digitally inclined (Igwe, 2010). Nigerian academic law libraries have always been innovative as their standards of operation are guided by Council of Legal Education and National Universities Commission (Sunday et al., 2017). Since these bodies regularly provide standards along the line of innovations, it could then be concluded that they are aware of the essence of collaboration and would recommend resource sharing standard for academic law libraries.

Survey research design was adopted for the study. The population consisted of 19 law librarians from Universities that attended 2017 law librarians’ conference in Nigerian Law School Abuja. Questionnaire was used to collect data. Due to the small population of law librarians, all the population was used for the survey. Mean and standard deviation were used with a likert point scale to determine positive (2.50 and above) and negative (2.49 and below). Research questions were analysed using frequency count, percentage, mean and standard deviation.

Document analysis

Answers to the research questions

This section presents the answers to the research questions. Each research question is presented with its table and then interpreted.

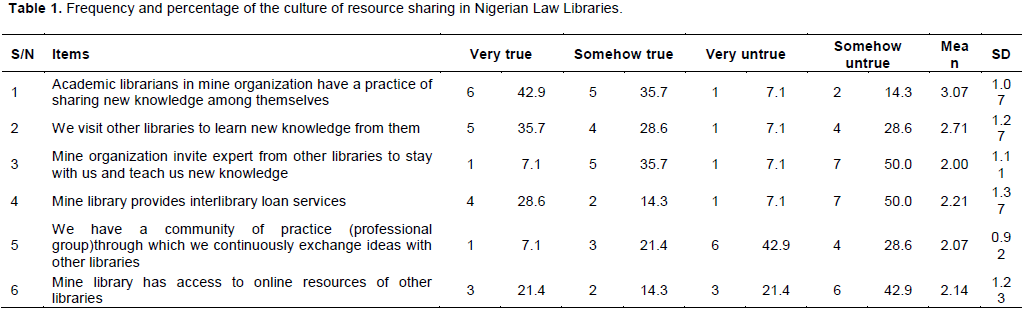

General question 1: What is the culture of resource sharing in Nigerian academic law libraries? In response to research question 1, it was revealed that the only culture of resource sharing applicable in academic law libraries are knowledge sharing practice. Table 1 portrays that academic law librarians voluntarily share their knowledge with other law librarians in other institutions and also visit them on their own to learn new knowledge. This sharing practise is self made as their institutions of base do not bring experts to share knowledge with them; more so, the practice of sharing information is not attached to any community of practice (COP). This means that practises that could provide information access to users are not applied, and so resource sharing does not directly benefit users but benefit academic staffs that go out on their own to informally share their knowledge with their colleagues.

General question 2: What is the financial help given to support resource sharing among academic law libraries in Nigeria?

In response to question 2, it was revealed that financial support is provided to law libraries and such financial support could support resource sharing. Furthermore, it was shown that law libraries receive much of their financial support from their university library and other organisations (Table 2). This implies that financial support is not responsible for non application of resource sharing practice among organisations.

General question 3: What is the written policy provided to support resource sharing among law libraries in Nigeria?

To answer question 3, it is shown that there is no written policy on resource sharing among the law libraries that participated in the survey (Table 3). This implies that resource sharing is not applied by law libraries that took part in this study.

General question 4: How do academic law librarians understand requirements for resource sharing in Nigeria?

In response to question 4, it is shown that the law librarians who participated in the study understand requirements of resource sharing (Table 4). This is because the question was couched negatively and the mean was just 1.71 indicating that it is not significant. This implies that majority of the respondents understand requirements of resource sharing.

The major results of this study show that:

(1) There is no formal practice of resource sharing among the participating law libraries.

(2) Law librarians informally share their knowledge on personal basis with their colleagues.

(3) Law libraries are supported financially by University Libraries and other organisations.

(4) Law librarians that participated in the survey understand resource sharing despite the fact that it is not practised by their libraries.

(5) There is no written policy on resource sharing among the libraries that participated in the survey.

The revelation on no resource sharing practice among participating law libraries confirms earlier finding in Owolabi et al. (2011) and Ogba (2014).

However additional knowledge was added to literature by the results which showed that law librarians on their own share knowledge informally by interacting with one another for their own personal development; although this could be seen as knowledge-sharing and not resource sharing per se. Despite this, it shows that resource sharing is an action that can be carried out where law librarians are encouraged to do so. Where the results of this study shows that the only sharing taking place is one done voluntarily towards knowledge enhancement; and judging by the fact that resource sharing is a formalised action that must be backed by required authorities (Sec.gov, 2009; Thompson, 2007), it then shows that academic law librarians in Nigerians would indulge in resource sharing activities when there is support by required authorities in charge of academic law libraries.

Although earlier study by Ogba (2014) on resource sharing ascribed the reason for non-sharing of resources to be inactiveness, however, this study has shown activeness on the part of the law librarians who enjoy collaborating for the sake of their own personal development. This study has therefore shown that the reason for non-sharing of academic resources in Nigerian law libraries is not within the ambit of law librarians but beyond them. More revelation showed that despite conclusions in previous studies that law libraries are not financially supported (Komolafe-Opadeji, 2011), they are actually supported financially by university libraries and other organisations as shown in the result of this study; thereby bringing it into discrepancy with findings in Komolafe-Opadeji (2011). Komolafe-Opadeji (2011) concluded that Nigerian libraries lack financial backing and so find it difficult to buy resources needed for academics; thus making it difficult for them to share resources. This discrepancy could be because the type of libraries studied in Komolafe-Opadeji (2011) is not academic law libraries which have strict monitoring by Council of Legal Education, Nigeria.

It was also revealed that law librarians clearly understood resource sharing despite the fact that they do not practise it; more so, they seek for their self development by visiting other libraries. This revelation again confirmed that there is a gap in research concerning the reason behind lack of interest towards the practice of resource sharing among academic libraries in Nigeria. It further shows that the reason for non-involvement in resource sharing practise is not as a result of apathy by law librarians as concluded in earlier study by Ogba (2014) but something beyond them. This is an area for further research; which is to find out why resource sharing practice is not implemented in Nigerian academic law libraries. Further results in this study that there is no written policy on resource sharing only confirms conclusions in previous literature like Owolabi et al. (2011) and further supports the conclusion in the result of this study that there is no resource sharing practice; for if there were an effective resource sharing practice, there would have been a policy that provides its base. More so, it confirms that the practice, as seen in Gross Archive (2018) where students visit other libraries and organisation with intention of getting resource assistance, is still in practice.

Based on the results of finding, it is recommended that Council of Legal Education take decisive steps towards initiation of resource sharing practice among law libraries in Nigeria.

CONTRIBUTION TO KNOWLEDGE

This paper has provided additional knowledge to previous literature on resource sharing. In earlier studies, excuses and challenges responsible for non-practicability of resource sharing in Nigeria were provided. They ranged from lack of funds, lack of information and communication technology to lack of electricity supply (Komolafe-Opadeji, 2011; Owolabi et al., 2011). Admittance, which was a universal culture of giving assistance to students from other law faculties, was seen as resource sharing practice (Owolabi et al., 2011). This study has provided additional knowledge by showing that despite the fact that resource sharing is not practised in Nigeria, academic law librarians have been collaborating and visiting other libraries in a bid to develop themselves; thereby showing the willingness on their part to collaborate towards resource sharing. This provides additional knowledge to the previous study in Ogba (2014) where it was shown that inactiveness or laxity on the part of law librarians was responsible for non-resource sharing practice among academic law libraries in Nigeria. This paper therefore has exonerated academic law librarians in Nigeria by showing that they are active and are not responsible for lack of resource sharing practice.

Furthermore, it has opened up a gap for hypothetical claim that management of Nigerian legal education are responsible for non-resource sharing practise in Nigeria. Also, by showing that academic law libraries receive financial support and have information technology amenities including academic databases; more knowledge has also been added, discountenancing earlier conclusion that lack of information technology and finance is responsible for non-resource sharing practise in Nigeria. The result of this study furthermore has described the features of resources sharing and in doing so in its literature review, has shown that academic law libraries in Nigeria have never practised resource sharing but have only been following a culture of help giving or what was called “admittance” in Owolabi et al. (2011).

Change is continuous and should be embraced where useful. Although it is difficult most times to embrace change; however where there is leadership that is geared towards development, then such required change becomes easy. The legal profession has had a culture of help giving which has become a norm; and so students move to other academic law libraries in search of materials not found in their own institutional law libraries. These students are not rejected and are given access to materials; however, they could also be rejected with no penalties awarded against the rejecting institution. A practice such as help giving carried out for long could be enhanced into a formalised resource sharing practice in order to make research easy for students and researchers who would not need to travel for their needed resources but could look through the catalogue of universities and select their materials. Where change is required to make life easy, then such change should be embraced with no delay.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Abubarka BM (2007). Resource sharing among libraries in Nigeria.TRIMV 3(2):105.

|

|

|

|

Archian AA (2020). Property Rights. Econlib. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Ali H, Owoeye JE, Anasi S (2010). Resource sharing among law libraries: An imperative for legal research and the administration of justice in Nigeria. Library Philosophy and Practice (E-Journal).

|

|

|

|

|

Boston University School of Law (2018). Fineman & Pappas Law Library Resources. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Gross Archive.com (2018). Impact of staff development in effective management of government parastatal (A case study of NEPA) Enugu district. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Igwe KN (2010). Resource sharing in the ICT Era: the case of Nigerian University Libraries. Journal of Inter-Library Loan, document delivery and Electronic reserve. pp. 173-187.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Komolafe-Opadeji H (2011). Use of internet and electronic resources amongst postgraduate students of a Nigerian private university. Information Technologist (The), 8(1):29-34.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nwofor FA, Ilorah HC (2015). Sustaining Nigeria's Democracy: Public Libraries as an Indispensable Instrument in Anambra State. Library Philosophy and Practice 0_1.

|

|

|

|

|

Ogba CO (2014). The practicality of resource sharing in academic law libraries in South Western Nigeria. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-Journal) P 1120.

|

|

|

|

|

Owolabi KA, Bamigboye BO, Agboola IO, Lawal WO (2011). Resource sharing in Nigerian University Libraries: A survey. Journal of Interlibrary loan, document delivery and Electronic Reserve 21:4.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rayner S, Walsby O (2012). EMTACL12 (Emerging Technologies in Academic Libraries). Ariadne 70 p.

|

|

|

|

|

Sec.gov (2009). Resource Sharing Agreement.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Sunday E, Onyekwere J, Chiedu B (2017). NUC, CLE bicker over accreditation of law faculties. The Guardian. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Thompson K (2007). Keeping your office sharing arrangements with other lawyers squeaky clean under the ethics rules. Aba model rules of professional Responsibility.

|

|