The introduction of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) to society has ripple effect on individual, social and political moral actions which may not be adequately addressed by existing theories of ethics. Information ethics provide a framework for considering moral issues concerning policies and practices regarding the generation, dissemination and utilization of information in Africa. This study established that information ethics education is a new academic discourse in Kenya and an emerging area of debate in LIS education. Respondents were of the opinion that knowledge in information ethics is important in LIS education and training in fostering academic honesty and respect towards scholarship. LIS departments have integrated information ethics courses in their curriculum, although the content coverage on ethical issues relating to the profession is inadequate. Information ethics is viewed as a supportive subject, thus topical issues relating to the subject are mainly integrated as part of mainstream LIS courses. A fully dedicated information ethics course would provide a forum for students to interrogate ethical discourse in the knowledge society and understand the legal grey areas following the rapid advancement in ICTs.

The utilization of computers creates new ethical issues which may not be adequately addressed by existing theories of ethics since they were developed before the advent of the information age (Floridi, 1999). Laudon and Laudon (2012) opine that the introduction of new information technology to society has a ripple effect, raising new ethical, social and political issues that must be dealt with on the individual, social and political level. Barroso (2011) asserts that recent social networks and communities contribute to socializing, sharing global knowledge, and helping to develop relationships between people, but there are problems related to basic human rights which could be damaged by the actions of these new technological tools.

Information ethics is concerned with moral dilemmas and ethical conflicts that arise in interactions between human beings and information systems in the creation, organization dissemination and use of information (Capurro, 2010; Carbo and Smith, 2008). It concerns all human activity related to how people generate, process

and distribute information in the form of new technologies and innovations (Babik, 2006). Ocholla (2009) asserts that the field provides a critical framework for considering moral issues concerning information privacy, moral agency, new environmental issues and problems arising from the creation, collection, recording, distribution and processing of information, especially ownership and copyright in view of the digital divide. The Tswane (2007) declaration resolved that policies and practices regarding the generation, dissemination and utilization of information in Africa should be grounded in ethics based on human values, human rights and social justice.

Information ethics in library and information science curriculum

Several authors have argued for the rationale for incorporating information ethics in library and information science (LIS) curricula (Kawooya, 2016; Dadzie, 2011; Ocholla, 2009; Carbo and Smith, 2002; Carbo, 2005). Recent increased cases of plagiarism, acts of hacking, academic piracy and violation of privacy in academic institutions the world over necessitate the need for ethical considerations especially in the information era (Bell, 2002). This is corroborated by Smith’s (2002) argument that the threats to information access, accuracy and privacy, and matters relating to the digital divide and alternative technologies demand immediate attention. Besides, information professionals have the responsibility to provide unfettered access to information and promote intellectual freedom and rights of information (Mutula, 2011). Fallis (2007) proposes that in order to deal effectively with ethical dilemmas, information professionals should have a good working knowledge of information ethics due to their role in the information society of gathering, processing, disseminating and using information. Equipping information workers with information ethics enables information mediators to verify quality and accuracy of information to clients and enables them to engage in ethical reasoning by determining what is wrong or right in a dilemma situation (Mutula, 2011).

The Information Ethics Special Interest Group (2007) suggested that information ethics would allow information professional to learn and understand their responsibilities and real consequences of their actions, and learn to use their power ethically and responsibly. Integrating information ethics in LIS curriculum builds a culture of responsibility among the youth using information technologies and to inculcate key principles of information ethics (Limo, 2010). It encourages LIS professionals to practice and apply correct moral and professional obligations in the performance of their duties (Ocholla, 2009). In support, Vagaan (2003) poses a question, “would LIS scholars and educators want their students to drive on the information superhighway without knowing the traffic rules?” Dadzie (2011) opines that information ethics education is important due to questions posed on the influence of ICT usage on moral values, and the unequal access to and use of ICT referred to as the digital divide.

Technology is developing a lot faster than the legal system and the law making process, therefore sometimes there is no legal protection offered against the misuse of new technology (SANs Institute, 2002). Laudon and Laudon (2012) note that individual’s actions are confronted with new situations often not covered by societal rules of behaviour, since social institutions may take years to develop etiquette, expectations, social responsibility, politically correct attitudes, or approved rules. Automated environments are unfamiliar worlds and peoples’ old intuitive habits of evaluation, which are adequate for determining what is best in traditional worlds, are inadequate in new and different settings (Severson, 1995). On the political front, institutions take time before developing new laws and often require the demonstration of real harm before they act, thus people may be forced to act in legal grey areas due to lack of laws that prescribe acceptable behaviour and promise sanctions for violations (Laudon and Laudon, 2012). Maina (2016) proposes that LIS schools in public university in Kenya should integrate information ethics courses in their curriculum to prepare students to be ethically equipped for the information profession in the current knowledge society.

Efforts have been made to entrenching information ethics education in Library and information science curriculum in Kenya, but there are inefficiencies of the information ethics content currently integrated in university curriculum (Otike and Maina, 2013; Limo, 2010; Kemoni, 2010; Otike, 2010). Incidences of information ethics violations manifested in the form of plagiarism, acts of hacking, breach of confidentiality and piracy have been reported in public universities, with plagiarism as the most prevalent among LIS students (Maina, 2016; Amunga, 2013). According to Limo (2010) and Amunga (2013), information ethics prohibit mischief like hacking and other internet crimes and reduce cases of academic malpractices. Kaimenyi (2014) urged universities to introduce undergraduate programmes on ethics so as to nurture students to be sincere and honest and be people of high integrity. He argues that introducing undergraduate programmes on ethics would expose students to standards of right and wrong practices that prescribe what humans ought to do; and that this will help them deal with personal and moral dilemmas that they face, and are likely to face when they assume offices of public trust. Limo (2010) argues that Kenya has skilled information science and ICT staff who need to be empowered to appreciate and exercise information ethics in industry. He states information ethics is important to LIS training notably to build a culture of responsibility among the youth using information technologies and to inculcate key principles of information ethics which include intellectual property, privacy and decency.a

This study sought to establish the necessity for teaching information ethics in Library and Information Science curriculum in public universities in Kenya. It draws from Kohlberg’s cognitive moral development theory (Kolhberg, 1984), which postulates that moral development is a process; therefore LIS students should be exposed to ethical activities that inform them on standards applicable to their profession and challenge their moral reasoning. The survey involved four public universities with established LIS departments namely Moi University, Kisii University, Kenyatta University and the Technical University of Kenya. The target population comprised of 6 heads of department (HODs) and 20 lecturers who were purposively sampled; and 252 students proportionately sampled from first to fourth year of study from the four LIS departments. The study was guided by the following research questions:-a) Which information ethics courses are covered in LIS curriculum? b) Why is it relevant to integrate information ethics courses in LIS curriculum?

Coverage of information ethics in LIS curriculum

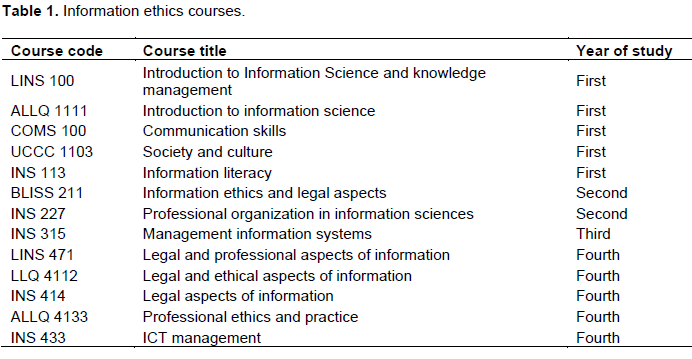

The study sought to find out whether information ethics topics were embedded into LIS curriculum. This was measured in three levels; whether students had done an information ethics course and if so, which were the information ethics courses, and if the knowledge gained from these courses was useful to LIS students. The study established that majority (67.1%) of students had done a course on information ethics, while 32.9% had not. This shows that although a high proportion of LIS students had been taught a course in information ethics, not all of them have had the privilege to pursue such a course. Responses from students who had done a course in information ethics indicating the code, courses titles and year of study are presented in Table 1.

The study found out that LIS departments have integrated information ethics courses in their curriculum, albeit shallowly. The courses are spread throughout all levels of undergraduate training, with a concentration of courses mainly in the first and fourth year of study. A common scenario in the four universities was the integration of information ethics topics as part of major LIS courses. It was established that information ethics was viewed as a supportive subject to other mainstream LIS disciplines. This confirms earlier studies that it is rare to find fully dedicated information ethics courses in LIS institutions in Kenya and this deprives the course considerable emphasis in coverage (Limo, 2010; Kemoni, 2010; Otike, 2010). Only three courses were fully dedicated to information ethics namely: - Professional ethics and practice; Legal and ethical aspects of information, and Information ethics and legal issues. Even so, triangulation of the responses from the three sets of respondents with content analysis from course descriptions and course outlines showed that these courses inadequately covered information ethics content on issues that relate to LIS practice in the knowledge society. HODs and lecturers pointed out that information ethics education is a new academic discourse in Kenya and an emerging area of debate in LIS education. Besides, they indicated that there was limited literature in the topic especially by African scholars, which has been reiterated by some authors that not much research in information ethics has been done in the Africa (Britz, 2013; Mutula, 2011). This reinforces Kawooya’s (2016) concerns if LIS programmes in Africa are preparing professional that are capable of navigating the difficult terrain of digital rights as well as engaging in legal and policy discourse on the digital rights that affect LIS institutions.

Regarding application of knowledge by students who had done an information ethics course, students were positive concerning the application of knowledge gained from these courses in handling ethical dilemmas in accessing and using information. Majority (61.5%) of the students indicated that they had been able to apply knowledge gained from courses in information ethics. Although the application of knowledge differed from one student to another, students majorly pointed out that they applied the knowledge in fostering academic honesty and respect towards academic scholarship. The knowledge gained from information ethics courses was important since the universities regulatory guidelines inadequately addressed information ethics issues. The rules and regulations that govern a student’s conduct while at the university are stipulated in the student handbook and university statutes, yet 167 (66.8%) students indicated that information ethics was not covered in the student handbook. Document survey confirmed the students’ statements on the omission of information ethics neither the penalties for violations. HODs and lecturers indicated that information ethics issues were briefly mentioned in the rules and regulations for undergraduate programmes. Particularly, the rules and regulations were not clear on what amounts to plagiarism and the guidelines do not include other information ethics violations that are emerging in universities. Besides, mechanisms to reinforce adherence to these rules were also found to be inadequate, since the regulations do not advice HODs on the measures to take in case of violation. Consequently, lack of supporting policy presents challenges in dealing with and containing the vices. Maina (2016) asserts that the plagiarism policies, severe punishment and plagiarism checkers introduced as deterrents to plagiarism in universities has assisted to instill adherence to and responsibility in research ethics, but its effectiveness in dissuading students from violations has been challenged.

Relevance of integrating information ethics courses in LIS curriculum

The findings supported the relevance of integrating information ethics in LIS curriculum in order to equip LIS students with knowledge in ethics. Lecturers, students and heads of department from LIS departments were of the opinion that an information ethics course is significant in LIS education and training. Responses by students on the relevance of the course are presented in Table 2.

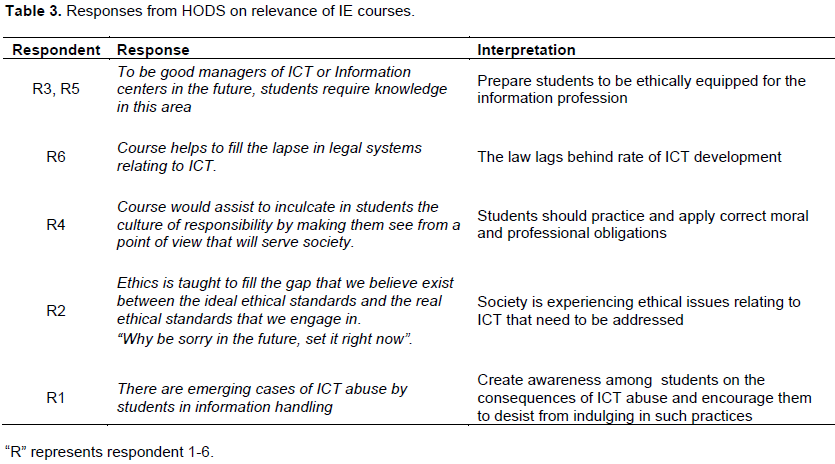

Students overwhelmingly (81%) agreed that information ethics courses were relevant to their studies. However, the study showed that a few (10.3%) students did not find the course on IE relevant, with a minimal (8.7%) number not certain on the relevance of the course to their training. This raises concerns on the limited awareness of information ethics in LIS departments and the command of content by lecturers teaching the courses. Similar responses were drawn from interviews with HODs as presented in Table 3.

It was established from HODs that LIS students need to prepared and equipped with knowledge in information ethics as future information managers. In particular, they emphasized the need to infuse information ethics in LIS education in order to encourage students to practice and apply correct moral professional obligations as students and later in professional practice. Lecturers supported this idea by stating that an information ethics course would help trainees to handle ethical dilemma faced in accessing and providing information as future information managers, and encourage LIS students to responsibly use and disseminate information. Mabawonku (2010) states that LIS departments have the responsibility to train students so that as practitioners, they would be able to educate the government, policy makers and the society at large on value of maintaining ethics in accessing and using information in decision making and problem solution.

The necessity for incorporating information ethics was linked to the need to prepare LIS students to practice and apply correct moral and professional obligations. Respondents were of the view that LIS students need to be equipped and empowered with relevant knowledge in emerging ethical issues arising from information and to prepare them to be responsible information producers and users at their training level and later at the workplace. The findings indicated that an IE course would assist to inculcate in students the culture of responsibility as information manager which resonate with several information ethics scholars (Ocholla, 2009; Vagaan, 2003). Limo (2010) states that as Kenya develops into an information society, LIS students and professionals should know the rules and regulations governing the information superhighway.

The study established that that the course would encourage responsible use and dissemination of information. Emerging incidences of information ethics violations and ICT abuses in society and LIS departments was noted. Respondents felt that the presence of these vices calls for immediate attention, and mitigation measures need to be put in place to check and address academic malpractices before the cases escalate. Respondents indicated that society is experiencing emerging ethical issues relating to ICT that needs to be addressed and checked before the cases escalate. Lecturers were of the opinion that the course would assist to reduce the increasing rate of plagiarism in universities.

The study noted that the rate of technology supersedes the development of legal frameworks. Respondents suggested that a course in information ethics was necessary in order to fill the gap in legal grey areas between the rapid advancement in technology and lapse in legal systems relating to ICT issues. Martin et al. (2005) observed that technology has evolved quite rapidly and legal systems have inevitably lagged behind. The findings showed that an information ethics course would enable students to understand and appreciated legal and ethical aspects of information hence decrease the legal lapse following faster rate at which technology advances.

Efforts have been made by LIS departments to incorporate information ethics in their curricula although the content is inadequate. University regulatory frameworks also do not adequately address information ethics issues. Integrating information ethics in LIS curriculum is essential in order to equip students with knowledge in ethics and inculcate a culture of responsibility among students using ICTs in the knowledge society. A course in information ethics would assist in checking and addressing emergent moral decadence in LIS, foster future LIS professionals with the culture of responsibility and help breach the lapse in legal systems. Besides this, as Kenya develops into a knowledge society, LIS students and professionals should know the rules and regulations governing the information superhighway for them to effectively and efficiently participate in development agendas.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.