ABSTRACT

Effective governance and leadership in non-governmental organizations (NGOs) does not happen by chance. Research has demonstrated that needed skills, abilities and competencies can make a difference. Using a model of 6 competencies that has been validated previously, these competencies have been used for governance and leadership training in the United States, Canada and Europe. This article reports the results of a 2017 anonymous survey of 185 respondents’ perceptions of the competencies of those in leadership roles and positions in Ukrainian NGOs. The overall summary finding is that five of the six competencies have moderate correlation to effective governance. While specific limitations may preclude the use of this model as a direct outline for training, consulting, strategic planning or other interventions, the competencies can be useful when translated into Ukrainian civil society.

Key words: Ukraine, governance, leadership competencies, civil society organizations.

Ukraine is at war, just not the kind with battles that make headlines while armies advance and retreat. But, since 2014, these "skirmishes" are just as deadly as major troop movements. "Russia-backed separatists continue to control areas in the (Eastern) oblasts/states, where violent clashes have resulted in over 9,000 deaths. A ceasefire agreement established a de facto dividing line between Ukrainian government-controlled and separatist-held areas of Ukraine. There have been multiple casualties due to landmines in areas previously controlled by separatists and both sides of the contact line are mined (U.S. Department of State, 2016)." Russia conquered, annexed and occupied Crimea. With the continuing hostilities in the eastern region, the country has had to adjust to over 2,000,000 internally-displaced people. They often left homes, families, friends, possessions and history to move to safer territory, some with family, some with friends, some with nothing more than hope.

The government in Ukraine has tried to respond to this crisis, but with limited success. Inflation compounds corruption, adding stressful burdens to the country. Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) often have a mission to help those in need. In the best of times, non- governmental organizations (NGOs) rarely had the resources to fulfill all their program needs. Thus, effective leadership is needed to guide these organizations. In the third sector, as Hodges and Howieson (2017) refer to NGOs and nonprofit, voluntary civil society organizations, "leadership is operating in a sector that is sensitive to social, economic, and political change and is still in a state of flux as its workforce and services respond to the drivers for change. This is placing significant pressure on traditional approaches to leadership which have to navigate the external environment, while attending to internal organizational issues including ensuring a consistent pipeline of funding, retaining independence, and the core mission of the sector (Hodges and Howieson, 2017)."

As such, leadership is a function, not a person, a set of skills available to guide, not a personality trait. Conducted in 2017, this research project documents the perceptions of members of Ukrainian NGOs in the leadership skills, abilities and competencies in the NGO, rather than in individual leaders. It uses a framework of 'best practices" from several decades' conceptual development and planned interventions to help NGOs maintain and improve their leadership effectiveness.

NGOS in civil society

Civil society consists of "the totality of groups and individuals in a country, who show a regular concern for the social and political context in that country, without fulfilling the function of political parties, who are autonomous from the government and (who) monitor the activity of the government or certain specific consequences of it, as well as to resist by legitimate means any unlawful, dangerous or abusive government activity (Balintova, 2009)". Civil society organizations (CSO) form a critical part of this international movement; they can serve to mobilize citizens for common purposes as well as to educate, advocate, monitor and challenge government when appropriate. As a category, CSOs can include trade unions, universities, religious organizations, media, think tanks, charities, associations and foundations.

Former UN Secretary General, Annan (1998) said: "The United Nations once dealt only with governments. By now we know that peace and prosperity cannot be achieved without partnerships involving governments, international organizations, the business community and civil society. In today's world, we depend on each other." Civil society is an independent sector that is organized outside the government to connect people to their local, regional, national and international leaders.

This research uses the well-established six competencies that characterize leaders in effective and successful NGOs. Initially proposed by Taylor et al. (1996), these have been used throughout the United States (Holland, 1991; Holland et al., 1989; Kovner et al., 1997) and less frequently in Europe and several post-Soviet societies (Ritvo, 2017; Ritvo and Feldman, 2015). Figure 1 defines the model.

Political

The NGO leadership "takes necessary steps to build and maintain good relationships with organization's stakeholders" (p. 17). This can also involve reconciling conflicting values within the NGO. For example, with limited funds, should an NGO put money into HIV/AIDS services to those in need (short term), help implement educational programs so clients and the public can learn how to prevent the spread of this disease (medium term), or fund research on a specific aspect of HIV/AIDS (long term). There is no 'right answer,' but rather a set of values that should guide the NGO is making this strategic decision. Reconciling differing values puts these political skills in action to avoid win/lose situations.

Educational

When effectively achieved, effective NGO leaders are "well informed about the organization and their roles and responsibilities (p. 17)." This includes a willingness to examine decisions, evaluate programs and services, thoughtful self-examination and learning from mistakes.

Interpersonal

Skills that help members of a team work well together make a difference. This competency does not mean there is never conflict; rather, the team "functions as a cohesive group and manages conflict effectively (p.17)." It assures that differences and points of divergence are handled in a manner that is respectful, task-focused and reaches closure when needed. The concept of 'we' replaces the voice of 'me.'

Strategic

Long term thinking that leadership must "keep a sharp eye on the future, identify trends in the social and political environment, and formulate responses that position the organization for future success (p. 18)." Continual reassessment of priorities, needs, successes and challenges helps organizations adapt to changing conditions. Leadership involves making strategic choices about allocation of resources, which needs to meet and which values should guide these choices. In summary, strategic competencies help define the DNA of an NGO: who are we and what do we stand for.

Analytical

These skills help leaders "in examining the complex issues the NGO faces (p. 25)." Starting from a broad organization-wide perspective, strong analysis looks at the many factors which may define a problem, could constrain different options, will encourage one course of action over another. Differences of opinion, perspective and understanding of proposed solutions are important; this not only prevents groupthink, but also helps assure a comprehensive understanding of the concerns-at-hand. An effective top leadership team will explore these differences, trying to reach a decision that will work in both the short and longer term.

Contextual

The leadership of the NGO is "conversant with issues facing the NGO and the larger society (p. 23)." As such, it can filter this information through the NGOs mission, traditions and values. Board members must understand the culture, values and norms of the NGO where they are in a leadership role. Decisions, programs and actions that are consistent with these elements strengthen the NGOs connections to stakeholders and empower members.

Best practices

The competency model for effective NGO leadership is based on using research results in practice, applying theory to the realities of leadership and management. Table 1 shows examples of these best practices in action.

Conducted online through a link to Google Forms, the Board Self-Assessment Questionnaire consisted of selected items from the original Holland et al. (1989) form. These questions describe the best practices of effective NGO leadership. The English Version was translated into Ukrainian and was available for respondents from February 24, 2017 through April 3, 2017. SPSS was used to analyze the data.

The self-assessment approach measures how respondents view their own organization. For example, if a director of an NGO were completing the form, that individual would be responding to how the questions applied solely to that NGO. It is not a measure of perceptions of the nation’s NGO leadership. Leadership in this research refers to those with governance and managerial decision making in an NGO.

The research questionnaire was disseminated using the snowball methodology. Initially, the online link to the questionnaire was sent to students, faculty and staff at the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv. These potential respondents could choose to delete the link or go to the survey. At the end of the questionnaire, respondents were asked to pass the link onto others who were leaders in NGOs. At no point did the researchers know the identity of any respondents, their location, employment status or any information about them. There is no information on how many chose not to forward the link. The process was totally invisible to the research team.

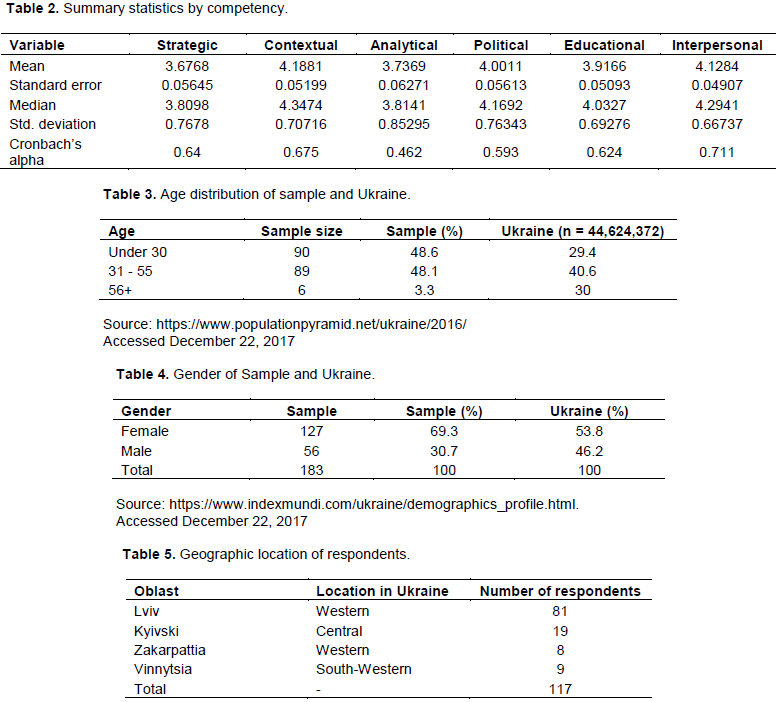

A total of 185 completed surveys were collected for analysis. Of these, 56 respondents were male and 127 were female. Ninety of the respondents were aged 30 or younger, 89 were aged 31 to 55, and only 6 were 56 or older. Nine different locations of activity within Ukraine and thirteen organizational missions were represented in the sample data. Summary statistics for the several assessed competencies are shown in Table 2.

The low reliability of the analytical competency measure is evidence that perhaps the questionnaire or the model it is based on is unsuitable in their current form for use in Ukraine. The several other measures are of marginal reliability, being in the interval from 0.6 to 0.7.

A series of analyses of variance were conducted to establish any significant differences in measured competencies across the various demographic variables observed in the data. The tests for gender revealed no significant difference across any of the several competencies. For age, there was a significant difference for political competency, with the older age groups scoring higher than the younger. No significant differences in mean score were apparent due to geographical region or primary mission.

Age

The age ranges of the respondents in this study are shown in Table 3. The sample is younger than the general population of Ukraine. Several factors might explain this finding, notably that younger generations are more connected through computers, tablet and cell phones. Since this was an e-survey, the access of older adults could have been a limiting factor. In addition, the questionnaire was distributed mainly to a population that was employed or volunteered in NGOs. A smaller, but unknown, number of respondents were recipients of service. Thus, this age distribution is not surprising. In addition, the older groups demonstrated significantly more political skills and competencies than their younger respondents. This may be due to the fact that experiences over time help builds one’s emotional intelligence, a key component of political skills is understanding others and adjusting accordingly. That is politics in action.

Gender

Table 4 shows the respondents who identified their gender were disproportionately female when compared with the national population demographics. While there are no reliable data on the gender of NGO managers, this sample seems intuitively non-representative of the larger leadership population.

Location

Table 5 shows the Oblast (regions which serve as administrative districts) of the respondents. It is decidedly tilted toward the western part of the country.

Field of practice/mission

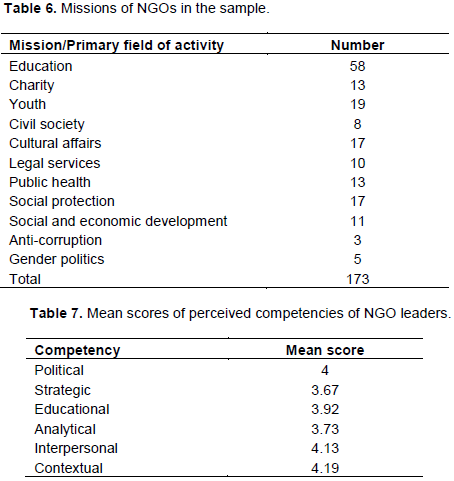

Table 6 shows the range of NGO missions represented in the sample. It is heavily skewed toward educational NGOs.

The respondents represent a wide range of NGOs in Ukraine. “According to the State Registry Service of Ukraine, there were over 50,850 registered civil society organizations in Ukraine in July 2013” (OSCE, 2015). Many of these have ceased operation or never became functioning programs. Thus, it is not possible to say that the sample represents all NGOs or not.

Competencies

Respondents were asked to assess the 6 leadership competencies of the NGO with which they were most familiar. Statements were presented with the following choices: (1) Strongly disagree, (2) Disagree, (3) Do not know, (4) Agree, (5) Strongly agree. Some questions were stated in the positive and scored using this methodology. Others were stated in the negative; scoring for these was reversed [Strongly disagreeing with a negative statement was scored as if the respondent strongly agreed with that statement if it were positive]. The mean results for each competency are shown in Table 7.

Converting these numbers into adjectives, means in the 4-5 range would be considered as demonstrating strong skills in these competencies. Results in the 3-4 range show perceived adequate and acceptable skills. The strongest competency in the survey was the contextual abilities (4.19). Leaders’ decisions are seen as supporting stated priorities and needs. On the other hand, the lowest mean scores were strategic (3.67) and analytical (3.73). Since many NGOs struggle to meet current needs, the concepts and practices related to data analysis and strategic planning for the next 3 to 5 years is a luxury that many administrators cannot afford. Just trying to meet payrolls, program services and client needs keeps the focus on shorter term demands.

Cronbach’s alpha analysis

Manerikar and Manerikar (2015) suggest that an alpha between 0.6 and 0.699 is “acceptable” [*] and 0.700 and 0.799 is “good” [**]. Four of the six competencies in this study meet these reliability criteria; one is almost acceptable (Political). Only the analytical competency falls below these parameters.

As a comparison, Holland and Jackson (1998) surveyed 693 board members in over two dozen NGOs in the United States. The results show major differences from the Ukrainian respondents. These data points were cited to show that the questionnaire itself may have different meanings in different cultures. NGO governance is still in its first generation in this newly-independent country, whereas the sample from the United States comes from mature organizations in a sector of society that is in its third century.

The Cronbach alpha results Table 8 show that the perceived leadership competencies in the Ukrainian sample are definitely lower than the sample from the United States (with the exception of the interpersonal competency). These pose both research and implementation concerns.

These results raise several important potential pitfalls if used as the basis for interventions, training or other administrative purposes. These should be explored both as concerns regarding research findings and managerial practices.

Cultural relevance

This research project is grounded in the work of recognized experts and professional organizations in the United States (Larcker et al., 2015; BoardSource, 2017; National Council of Nonprofits, 2017) which analyzed in-depth nonprofit organizations in a variety of fields (education, museums, community service, cultural, etc). The best practices that emerged formed the basis for the six-competency model for effective governance and leadership.

As noted, there have been a limited number of studies that use this model outside the United States. Therefore, it is prudent to ask if these 'best practices' are global or limited more to the United States. Does the competency model apply in Ukraine? It appears not. If used, does it require adaptation/almost certainly yes.

Sample versus Ukraine

The sample in this research is younger and has greater female representation than the general Ukrainian population. The authors draw no conclusions as to how this might bias or skew the results.

Over-representation of educational NGOs

This may have resulted from the interaction of several factors. One is that educational organizations tend to be larger than traditional, service-focused NGOs. When combined with the culture of research and knowledge-building that is part of their mission and jobs, employees in these organizations may be more inclined to complete an anonymous questionnaire. A third factor might be that the 600+ members of the Ukrainian Catholic University might have wanted to help colleagues, even if they did not personally know them.

Over-representation of Lviv and Western regions

Since the university supported this research project, the initial elements of the snowball methodology started with email lists of university-affiliated members and their contacts, friends and colleagues who were members of NGOs. Perhaps given a longer open response period, the sample might have included a great number and percentage of people from the central and eastern regions.

Different sample criteria

The studies and professional training programs based on this model of board competencies have centered on, and limited to, current board members. This study in Ukraine expanded the sample to include NGO professional and lay leaders. While the skills needed are congruent, this more inclusive sample may account for some of the variance.

In closing, the broad context of NGOs in Ukraine sets the table for the work of NGOs in all sectors of society. Ukraine is still relatively young emerging democracy which endeavors to establish new institutions, traditions and aspirations. Lyubomyr Husar (1933 - 2017), the ex-leader of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, reflected on the dramatic shifts in Ukrainian society during his lifetime. “I know that many people are disappointed that (the 2014 Revolution of Dignity in Kiev’s Maidan Square) did not bring quick changes. But the question of whether we are moving at a fast or slow pace is much less important than the question if we are moving or standing in place. Do we make a decision each time to become better than before, are we ready to change?” NGOs have a role to play in enhancing the emerging Ukrainian civil society; hopefully, the competencies explored in this research can assist in some small way moving toward this broader vision.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of Dean Rhea Ingram, the AUM University Research Council and Professor Natalia Bordun at the Institute of Leadership and Management at the Ukrainian Catholic University. Without their support, this research would not have been possible.

REFERENCES

|

Annan K (1998). Address to the World Economic Forum. New York: United Nations Office of Communications.

|

|

|

|

Balintova S (2009). Civil Society – A Hope against Corruption in Central and Eastern Europe. New York: Open Society Institute. Website accessed February 3, 2017.

View

|

|

|

|

|

BoardSource (2017). Board Openness to Strategic Alliances & Restructuring: Survey Report.

View Website accessed September 15, 2017.

|

|

|

|

|

Hodges J, Howieson B (2017). The challenges of Leadership in the Third Sector. European Management Journal. February 2017, 35(1):69-77.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Holland TP (1991). Self-Assessment by Nonprofit Boards. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 2:25-36.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Holland TP, Jackson D (1998). Strengthening Board Performance: Findings and Lessons from Demonstration Projects. Nonprofit Management and Leadership 9(2):125-37.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Holland TP, Chait R, Taylor B (1989). Board Effectiveness: Identifying and Measuring Trustee Competencies. Research in Higher Education 30:435-453.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kovner A, Ritvo RA, Holland TP (1997). Board Development in Two Hospitals: Lessons from a Demonstration, Hospital and Health Services Administration 42(1):87-99.

|

|

|

|

|

Larcker D, Meehan W, Donatiello N, Tayan B (2015). Survey on board of directors of nonprofit organizations. Harvard Business Review, September, 2015,

View Website accessed August 12, 2017.

|

|

|

|

|

Manerikar V, Manerikar S (2015). Research Communication: Cronbach's Alpha. aWEshkar 29(1):118.

|

|

|

|

|

National Council of Nonprofits (2017). Board Roles and Responsibilities.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) (2015). Thematic Report. Civil Society and the Crisis in Ukraine. March, 2015.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Ritvo RA (2017). Developing NGOs in Post-Soviet Azerbaijan: Expanding Kurt Lewin's Ideals. American Journal of Business and Society 2(1):1-9.

|

|

|

|

|

Ritvo RA, Feldmann A (2015). Corporate Social Responsibility in Latvia: Building Partnerships and Public Support for NGOs. Journal of Management Policy and Practice 16(2):26-37.

|

|

|

|

|

Taylor B, Chait R, Holland TP (1996). The New Work of the Nonprofit Board. Harvard Business Review pp. 36-47.

|

|

|

|

|

U.S. Department of State (2016). The Department of State warns U.S. citizens to avoid all travel to Crimea and the eastern regions of Donetsk and Luhansk.

|

|