Over the years, we have seen the growth of Non-governmental Organizations (NGOs)' activities in Bangladesh and their massive influence on its development process. This article looks at the field-workers employed by local NGOs in Bangladesh. This paper's main objective is to find out funding pattern, project continuation, and their effects on field workers' careers. A total of 50 respondents were randomly selected from 10 local NGOs of the Rajshahi City Corporation Area (in the north-western part of Bangladesh). It was found that NGOs' foreign funding declined in Bangladesh due to its transformation to a middle-income economy. A large number of field-based workers lost their jobs from local NGOs due to fund crisis. Current development workers were worried about their job. Their lives and livelihoods were at risk. Almost every aspect of Bangladesh's socio-economic development has had local NGOs' input, including women's development, microfinance, education, and health. Services of field workers are still very much needed.

The work of NGOs in Bangladesh started as far back as the British colonial period. The country's strong virtues of voluntary work have been deeply ingrained in its economic, religious, and social conditions. The British era came with several religious trust-based schools, orphanages, and hospitals, representing NGOs in their crude forms. The NGO's course in Bangladesh underwent a radical upgrade in 1971. This made it a crucial aspect of national efforts committed to poverty alleviation in Bangladesh. Subsequently, there were increased NGO-based contributions to essential aspects of the welfare system, including family planning and Mother and Child Health (MCH), non-formal and formal education, legal aids, advocacy, and human rights, poultry and livestock, agriculture, gender development and in many other fields (Mohiuddin, 2002). NGOs of Bangladesh have a good access at grassroots and hard-to-reach areas with commendable creditability.

According to the World Bank's definition of NGOs, they are private organizations committed to easing suffering, pursuing the poor peoples' interests, offering essential social services, protecting the environment, and championing community development. The WHO further divided operational NGOs into three groups: (a) The community based organizations (CBOs), which cater to a particular population in a smaller geographical area. They undertake individual responsibilities compared to other NGOs. (b) National organizations operating in separate developing nations, (c) International organizations pursuing the NGOs' interests in multiple developed countries, while being headquartered in such developed countries (World Bank, 1995). The NGO movement is not all that perfect; there are few degenerations and contradictions spread across board. But despite these challenges, the system has played crucial and positive roles in important areas. For instance, they have created alternative credit institutions that see and treat women as worthy borrowers while reducing conventional money lenders' powers. They have also provided services in health and education in rural areas (Muhammad, 2018).

In Bangladesh, local NGOs usually work in 2/3 Thanas (sub-districts) with local offices and programs limited in small areas. Some funds are raised locally, and rest usually comes from foreign donors (Ahmad, 2001). A total of 2,336 Local NGOs are working in Bangladesh (NGO Affairs Bureau of Bangladesh, 2018). NGOs create opportunities for employment for a considerable number of Bangladeshi and foreigners. However, field workers could be the movers and shakers of NGOs. They are engaged for implementing organizational decisions, but their pains and pleasures are merely heard during the organizational policy formulation process. They are policy victims and forgotten segments in the whole operational procedure of NGO. Female field workers have to carry huge workloads silently. In some extent, the working situation is monotonous in nature. The welfare of NGO workers has been moderately considered by top management. They face professional problems with a lack of proper training, promotion, suitable transfer, and amusement facilities.

The Bangladesh Financial Intelligence Unit collaborated with the Bangladesh Bank (the central bank) and the NGO/NPO Sector Regulatory Authorities in 2015 to carry out an extensive survey on NGOs' impacts. The findings showed that initial donor-driven NGOs relied on local funding sources due to the shortage of foreign funding. Foreign funding to NGOs through the NGO Affairs Bureau declined by 15% year-on-year in fiscal 2015-2016 after the careful government watch on their operations. In 2015-2016, the NGO Affairs Bureau released $640.55 million in grants, down from $749.86 million a year earlier. The bureau approved about 1,100 projects on average in the last few years, but in 2015-2016 it came down to 986 (The Daily Star, 2018) (Figure 1).

This paper sets out to explore the funding situation of local NGOs in Bangladesh. It also addresses changes in local NGOs' funding patterns over the last five years and its implications on their existing field-workers' socio-economic conditions. If a field worker loses his/her job due to completing the project and fund crisis, he/she could look for a new job.

Research questions

The three major research questions addressed in this paper are:

(1) To find out changes in the funding pattern of local NGOs from 2013 to 2018.

(2) To find out the relation between funding and project continuation.

(3) To assess conditions of existing and quitted field-workers of local NGOs.

This research adopts both quantitative and qualitative methodologies in collecting, assessing, and analysis of data. Fieldwork was conducted in Rajshahi City Corporation Area (in the north-western part of Bangladesh) from August to September 2018. A total of 10 local NGOs were purposively selected for the collection of data and information. These were BUP, CCBVO, PARTNER, RULFAO, SACHETAN, SBMSS, SGUS, SHAWUNNAYAN, SNKS, and TRINAMOOL. These NGOs mainly work in the Rajshahi district and City Corporation Area. A total of 50 respondents were randomly selected from 10 local NGOs. Table 1 provides information about age, religion, educational qualification, and marital status of the respondents who were current and quitted field-workers from local NGOs.

Program interventions

Selected NGOs mainly work in the field of human rights, good governance, child rights, women rights, health and education, water and sanitation, rights of ethnic minorities, domestic violence, legal aid support, rights of a person with a disability, safe migration, drug prevention, Vulnerable Group Development (VGD) monitoring, khas (government) land, food security, environment, and microcredit. The majority of the NGOs (70.00%) were working in these fields for more than 25 years.

Funding pattern and employee

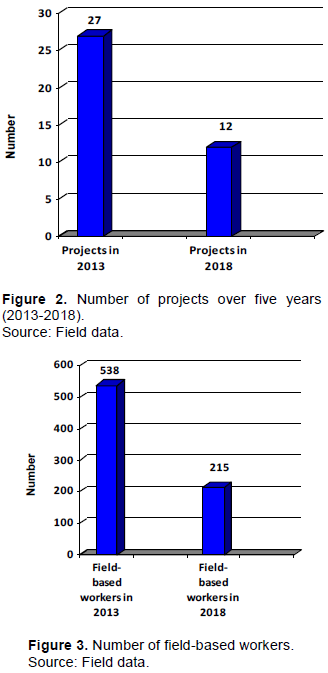

Some NGOs were very reluctant to disclose the details of the funding. Thus, it was difficult to analyze gross trends over the years. By and large, it was found that one NGO, out of 10, expended program interventions by increasing the number of projects, that is, from one to three over five years. In 2013, rest nine NGOs were operating 27 projects in different areas. However, it went down to 12 in 2018. Two NGOs closed their operations due to the funding crisis. However, it was found that some NGOs were fully donor-dependent. Donor funding and project continuation were positively correlated. The majority of NGOs (80.00%) did not have their own strategic and fundraising plan. They implemented donor-driven projects. Six NGOs had a bitter experience to retrench their field-based staff due to the fund crisis. In 2013, a total of 364 male and 174 female field-workers were employed in nine NGOs. The number of employees decreased in 2018, that is, reached 145 male and 70 female field-workers. In all, field-based development workers were reduced by 60% in five years (Figures 2 and 3).

Quitted field-workers

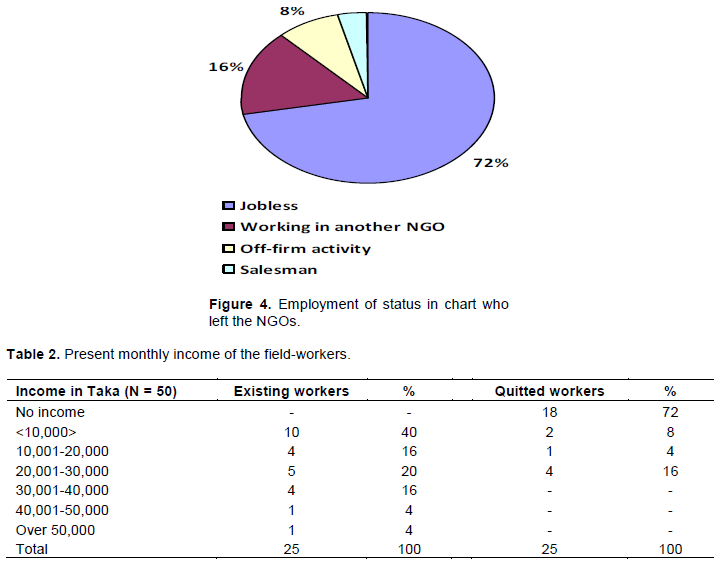

A total of 25 respondents were randomly selected who quitted from the NGOs in the last six months. It was revealed that the majority of them (80%) quitted due to fund crises and completion of the project. Others quitted because of better opportunities and other causes. Figure 4 shows the present job of the quitted field-workers.

It was found that 72% of quitted field-workers were jobless. The majority of them were earning Taka 15,000 to 25,000 (USD $188-$313). They had job experiences varied from 5 to 25 years with a set of specialized skills. All of them had post-graduation education. Those who have joined as a salesperson for different companies told us that they could not cope with a new job immediately because they were engaged in another kind of work for long. They also said that their lives and livelihoods were in a miserable condition.

Income distribution

The majority (56%) of existing field-workers received their monthly salary regularly. The monthly salary of other workers was irregular. However, all respondents were satisfied with the present salary. They only wanted a continuation of the job, that is, job security (Table 2).

Other benefits

The majority (68%) of the existing field-workers revealed that their organization did not provide them gratuity, provident funds, and medical allowance. All respondents were satisfied in terms of working hours, leave, travel allowance, and daily allowance. They told us that they wanted to have a job in such a critical situation.

Future scenario

Existing field-workers were always in tension to lose the job due to the ongoing fund crisis. The majority (60%) of them could not save money for the future due to the high cost of living compared to their salary. They felt that their future lives are in uncertainty. The majority of field workers who had lost their jobs passed difficult situations in buying food, paying house rent, providing education of their children, healthcare, and social responsibilities. The family size of the majority of respondents (68%) is between three and five members. However, jobless field-workers still expected that their employers would call them for a job. It was found that local NGOs give priority to appointing their former staffs when they need people after they get new projects.

Case study-1

Ms. Tahera Khatun is 44 years old. She completed her MA from Rajshahi College, Bangladesh. After completing post-graduation, she joined in Proshika Manobik Unnayan Kendra (a renowned NGO of Bangladesh) as a field worker. In 1998, she was posted at a remote village of the Hossainpur sub-district under the Kishoreganj district with a monthly salary of Taka 4,000/-. She was mainly responsible for microcredit and legal aid services to needy women. She resigned from Proshika in 2008 and joined at SHAWUNNAYAN (a local NGO of Rajshahi district). She was the field coordinator of SHAWUNNAYAN and worked on legal aid supports to underprivileged communities. Unfortunately, her husband died in 2012, and she became the single earner of the family. Now she has two sons. The elder son is studying in Rajshahi University, and the younger one is reading in class ten. Somehow, she was maintaining family life with a limited salary of Taka 10,000/- for working as a field worker in a local NGO. She dreamed of a bright future for her sons. But SHAWUNNAYAN was closed down in June 2018 due to fund crisis. Many field workers lost their jobs like Ms. Tahera. She did not get any provident fund and gratuity because she worked on a project. Now she is passing a very miserable life at a rented house in the poorer part of Rajshahi city. She was finding it difficult for her to continue the education of her sons. She is searching for a job as a field worker, but not getting due to a fund crisis in the local NGO.

Case study-2

Mr. Arif, 42 years old, is from a very poor family. His father was a farmer and died at an early age. He completed graduation from New Government College, Rajshahi, Bangladesh. Mr. Arif was not able to complete post-graduation due to economic hardship. However, he joined a local NGO, RULFAO, in 2002 as a field worker. His monthly salary was Taka 2,500/-. He had 16 years of experience in the same organization. He worked in different areas like microcredit, health and sanitation, and education. He did not change organization due to job security, and he loved the organization because of its good working environment. Mr. Arif has three children, wife and an old mother. His mother is severely sick due to old age complications. However, he was maintaining family and mother's treatment by his monthly salary Taka 10,000/-. Unfortunately, he lost his job in 2018 due to fund crisis, and he became jobless. After a few months, he joined in a local company as a salesman and was based on his sales performance. Now this monthly salary is Taka 5,000/- that is also irregular. He said that he could not cope with new job suddenly due to long time working in a specific field. His life and livelihood were in miserable condition.

Foreign funding for NGOs has been declining in Bangladesh with the country moving into middle-income status. It seems highly educated, and skilled field-based development workers are in vulnerable condition. This severe funding crisis threatens the lives and career of Bangladesh’s local NGO field workers. One option could be that NGOs look for government funding and join them in implementing government projects; many field workers suggested that. NGOs have been playing a vital role in the country's socio-economic development, especially in health, education, microfinance, and women development. Their services are still very much needed.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

Sincere appreciation goes to Md. Aminul Islam, student of the social work department, Rajshahi University, and Md. Abdul Halim, Rajshahi College, for helping during fieldwork. The authors are also indebted to the respondents who sacrificed their valuable time by providing data and constructive thoughts.