ABSTRACT

Traditional medicine (TM) is an important source of care for most poor people. Aware of this role, most African countries have developed national policies to give legal status to TM and its practitioners. Currently, at least 30,000 people practice TM in Burkina Faso. However, few, particularly women, have licenses to practice TM. This paper presents the results of a pilot project that aimed at accompanying the traditional women healers from Sanmatenga province in obtaining licenses. The application for TM practice includes personal attested documents and ethnomedical evidence or proof of efficacy of the traditional product. To assess the ethnomedical evidence, the traditional healer is monitored by a nurse over a four-month period during which the nurse follows patients receiving the traditional treatment. The nurse investigates the work of the traditional healer and its final report includes its opinion on the traditional healer and the number of patients followed, cured or lost after treatment with the traditional product. Perceptions of different stakeholders regarding the intervention were obtained through unstructured interviews. 60 traditional women healers were selected from three health districts of the province of Sanmatenga. They were followed by 10 nurses. Currently, about 37% of traditional women healers are licensed. Findings showed that the different stakeholders welcomed the intervention and made recommendations to strengthen this relationship. Thus, strengthening the capacities of traditional healers as well as the collaboration with conventional medicine practitioners contribute to build stronger healthcare systems.

Key words: Traditional medicine, traditional women healer, conventional medicine, license, ethnomedical evidence, healthcare system.

Abbreviation:

TM, Traditional Medicine; CM, Conventional Medicine; CMP, Conventional Medicine Practitioners.

Depending on whether it is called, traditional, complementary or alternative medicine, its use by populations, is still growing worldwide. Traditional medicine (TM) is defined as “the sum total of the knowledge, skill, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness”, whereas the term complementary medicine or “alternative medicine” is related to “a broad set of health care practices that are not part of the country’s own tradition or conventional medicine (CM) and are not fully integrated into the dominant health-care system”(World Health Organization, 2013). The assumption that African traditional medicine is the oldest therapeutic system comparatively to other health care systems has been advanced by some authors (Mahomoodally, 2013; Agbor and Naidoo, 2016). “African traditional medicine” is related to a set of “all practices, measures, ingredients, and procedures of all kind whether material or not which guard against disease/illness to alleviate suffering and cure himself” (Innocent, 2016). As a result, treatment in African traditional medicine uses a holistic approach which include divination, spiritualism and herbalism (Innocent, 2016; Ozioma and Chinwe, 2019). A traditional medicine practitioner or healer is “a person who is recognized by the community where he or she lives as someone competent to provide health care by using plant, animal and mineral substances and other methods based on social, cultural and religious practices”(World Health Organization, Western Pacific Region 1999). African traditional healers can be classified as diviners, herbalists and faith-based healers (Mokgobi, 2014; Zuma et al., 2016; Kpobi and Swartz, 2019). The first category regroups healers who use ancestors’ spirits to diagnose and treat disease, the herbalists have important knowledge in the use of herbal mixtures and the faith-based healers practiced deliverance and healing by using religion (particularly Christian and Islam religions). There may be subcategories within these main groups: traditional bonesetters, traditional birth attendants, traditional psychiatrists and traditional surgeons (Amzat and Razum, 2018). Moreover, some traditional healers may combine at least two or more healings methods as when a diviner or faith healer use parts of medicinal plants for healing purposes.

In many urban and rural areas of Africa, people used to consult a traditional healer before they seek for a conventional medicine practitioner (CMP) (Abdullahi, 2011; World Health Organization, 2013). According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the ratio of traditional healers to population is 1:500 while the ratio for conventional medicine doctors is 1:40 000 in Africa (World Health Organization, 2013). This is why the call for a collaboration between TM and CM is important since traditional healers may improve accessibility to a basic health care in the rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa (van den Geest, 1997; Moshabela et al., 2017).

Regarding the importance of traditional medicine to reach the sustainable goals and universal health coverage, WHO has advocated for the integration of T&CM into the health systems. Since 1999, WHO has recommended its implementation through the development of national policies, regulatory frameworks and strategic plans for T&CM products, practices and practitioners (World Health Organization, 2019). Integration is considered as an increase of health coverage through collaboration, communication, harmonization and partnership building between conventional and traditional systems of medicine, while ensuring intellectual property rights (IPRs) and protection of traditional medical knowledge (Sambo, 2003). A recent report revealed that at least 50% of the WHO members states had a national policy on T&CM by 2018 (World Health Organization, 2019). The recognition of TM into state’s national policy leads to characterize four main health care systems: “integrative” in which TM is officially recognized and full incorporated into all health care provision areas (practitioners, products, availability of therapies in all health care levels, reimbursement of treatment charges,…), “inclusive” where TM components are not entirely integrated in the public health care. In the “tolerant” system, TM practices are tolerated by law but are weakly integrated and the latest system is an “exclusive” system in which TM and its practices are proscribed (Gqaleni et al. 2007; Payyappalli, 2010; Ijaz and Boon, 2018).

Burkina Faso, a landlocked country located in West Africa, has adopted a national policy entitled “National Policy Framework on Document Traditional Medicine and Pharmacopoeia”. The national policy regulates the practice of TM, the monitoring of TM practitioners, the marketing of approved traditional products and the establishment of a framework for collaboration with modern medicine practitioners (World Health Organization, 2001, 2019; Burkina Faso Ministry of Health, 2018). Being TM practitioner in the country requires a license from the Ministry of Health. The authorization to practice TM is given to those traditional medicine practitioners who demonstrated good moral and good reputation in her/his community.

The application for license to practice traditional medicine includes personal documents (for instance, birth and nationality certificates, a criminal record, a residence certificate and a commitment to respect medical ethics signed by the applicant) and the proof of the ethnomedical evidence of traditional product. The ethnomedical evidence of a traditional recipe is a product whose proof of efficacy is provided (Sambo, 2003). The confirmation process is conducted by a nurse. Firstly, the nurse diagnoses the disease; secondly, the patient is treated with the traditional recipe; thirdly, nurse realizes the biological follow-up of the patient and conducts an investigation on the traditional healer. Finally, the nurse writes reports including the number of patients treated with the traditional product, the number of patients lost, the number of patients cured clinically, the cure rate and expresses its opinions about the traditional healer. The license to practice TM is issued to those traditional healers who have treated at least 30 patients with a cure rate greater than or equal to 90%. Furthermore, the license is valid for the treatment of no more than three diseases and is obtained after an evaluation by a national expert committee set up within the Ministry of Health. The committee is expected to meet once every three months.

According to the Burkina Faso National Traditional Healers’ Federation (FENATRAB), there were about 6,00 traditional healers licensed to practice TM in 2008 (Maiga, 2018). Among them, there was practically no woman granted license for TM practice, especially in rural areas. This fact can be explained by a number of reasons, some of them are poverty, lack or little access to education and training and lack of information about how to obtain the license of TM practice although this latter reason concerns both women and men.

This paper presents the results of a pilot project that aimed to help traditional women healers of Sanmatenga province (Burkina Faso) in obtaining license to practice TM. The paper examines the licensing process and seeks to understand the attitudes of TM healers and conventional medicine practitioners (CMP) regarding the licensing procedure and the collaboration between TM and CM. It is a contribution to the efforts directed to fill the gap between traditional healers and conventional medicine practitioners.

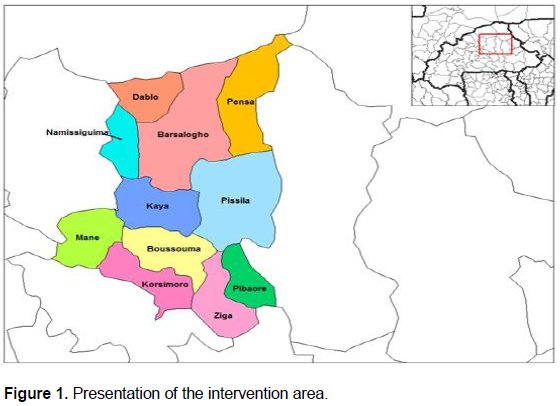

Intervention area

The intervention was held in the province of Sanmatenga situated in the Centre-North Region of Burkina Faso during the period between October 2016 and December 2017. Sanmatenga is located at 13°15?00? N and 1°05?00? W and at least 100 km from Ouagadougou, capital city of Burkina Faso. The province comprises eleven departments (Figure 1) and three health districts: Barsalogho, Kaya and Boussouma. The intervention was conducted in eight localities of the province, including Barsalogho, Korsimoro, Ziga, Kaya, Pissila, Pibaore, Mane-Tanzeongo and Mane-Centre.

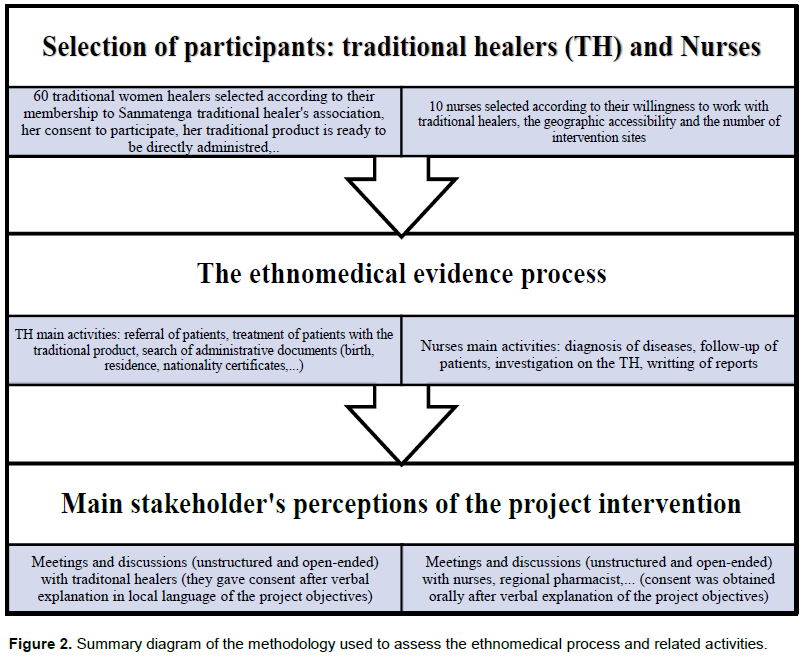

Selection of participants

Before the recruitment of the participants, meetings were organized between the project team and the Sanmatenga province authorities (administrative, customary and religious), the health care managers, that is, the regional health director, the heads of health districts, the regional pharmacist and the traditional healers. This was undertaken to obtain the permission and support to conduct the project. Two groups of participants were included in the present intervention: the traditional women healers and the nurses. To be included, the traditional women healers have to meet the following criteria: (i) be a member of the Sanmatenga Traditional Healers’ Association, (ii) give her consent to participate to the project, (iii) her traditional product must treat a priority disease such as malaria, hypertension, diabetes, infection diseases and (iv) the traditional product is a herbal product ready to be administrated to the patients. This product may contain the main active ingredients with other plant materials or combinations.

In the national health policy, the person contact of the traditional healer is the head of the primary health center. This person is a nurse. Nurses were selected based on (i) their interactions with the traditional healers, (ii) the geographic accessibility of the primary health center and (iii) the number of the intervention sites. Each nurse had to follow/support at least 5 traditional women healers. Furthermore, ten traditional male healers (focal points) were selected to help/support the traditional women healers and act as intermediary between the nurses and the traditional women healers.

In total, the final sample comprised 10 nurses distributed as follow: (1) for Barsalogho, (2) for Mane (1 for Mane-Centre and 1 for Mane-Tanzeongo), (3) for Kaya, 1 for each of the following sites, Pissila, Pibaore, Korsimoro and Ziga. The final sample size of the traditional women healers was 60 women.

Ethnomedical evidence process

To prove the efficacy of the traditional product, the following steps and related activities were conducted:

(i) Training: the traditional healers (the selected traditional women healers and some traditional men healers from the Sanmatenga Traditional Healers’ Association) were trained by the staff of the health district of Kaya to recognize and manage symptoms of priority diseases including malaria, hypertension, diabetes and some infectious diseases. The training session was realized in a local language, namely Moore, due to the lack of conventional education of the majority of these traditional healers. During the training, they received notebooks serving as the patient medical record. This document contains especially the date on which the patient was received, the patient identification information and the given treatment. To fill the medical record, traditional healers got help from their family members (particularly from the students).

(ii) Referral of patients: Before recipe administration, the traditional healers ensure of what the patient is suffering from referring her/him to the primary health center. There, the nurse makes a diagnostic of the disease through available biological tools: a rapid malaria diagnostic test or measurements of body temperature and blood pressure. The nurse gives the test result and the patient can choose traditional or conventional treatment.

(iii) Return of patients: After the traditional treatment, the traditional healer meets the patient and she/he notes recovery or any other possible results (a deterioration of the patient's general condition requiring hospitalization). Regardless of the result, the traditional healer referrers again the patient to the nurse who confirm the effectiveness of the traditional product.

(iv) The traditional healer and the nurse meet together once a month: the nurse verifies the filling of the notebooks (patient medical records) and discuss with the traditional healer about any possible difficulties. In this experience, the monitoring of TM healers was assessed over a four-month period.

(v) The nurse investigates on the traditional woman healer. He meets and discusses with the community members where the traditional healer lives. Then, she/he writes two reports including the clinical follow-up result and his opinions on the work of the traditional healer.

(vi) Quarterly meetings with the project management team: the role of the project management during the process of ethnomedical evidence was mainly observational; they observed and reported the effect of the intervention without disturbing the main actors. Discussions are organized with nurse, traditional women healers and focal points in order to state on the ongoing collaboration, identify and solve any possible issues.

Perceptions of key stakeholders

The management team worked at building a collaborative environment with the different stakeholders. The management team trained the traditional healers (good plant harvesting, drying and conserving practices), helped them obtain some administrative documents required for the licensing process and initiated collaboration with conventional medicine practitioners. Throughout the intervention, discussions, though unstructured, were held with the traditional healers (men and women), nurses and some province health care managers (regional pharmacist, heads of health districts) to understand their perceptions of licensing process and the initiative to help traditional healers obtain the authorization to practice TM. The discussions with the traditional healers were carried out in Moore (local language) and in French with the CMP. A consent was obtained orally before the start of the discussions with the stakeholders and after verbal explanation of the intervention objectives. Figure 2 summarizes the different activities realized (participants selection, assessment of the ethnomedical evidence and perceptions of main stakeholders).

Number of traditional healers licensed

Before the intervention, almost no traditional woman healer was licensed. At the end of the project (end of year 2017), 13 traditional healers, including 8 women and 5 men, obtained authorization to practice TM. From the end of the project to the end of the year 2019, there was 14 women and 7 men traditional healers (Figure 3). Therefore, there were 22 traditional women healers (about 37%) and 12 traditional men healers who have obtained licenses to practice TM in the province of Sanmatenga.

In terms of distribution by health district, 16 traditional women healers (about 73% of female recipients) were from Kaya health district and 6 (about 27% of female recipients) from Boussouma health district. To date, no traditional woman healer from the health district of Barsalogho has obtained the license. The recipients treated several diseases which include but not limited to malaria, asthma, high blood pressure, diabetes, diarrhea, stomach ulcer, hepatitis, mycosis and typhoid fever.

Perceptions of the stakeholders

Health staff

The Sanmatenga province health staff whatever their quality, that is, regional health head, heads of health districts or regional pharmacist, positively appreciated the initiative. The project has received their support and they greeted the idea of strengthening collaboration between conventional and traditional medicine. To the best of their knowledge, it was a first time that an intervention aimed at helping traditional healers, especially women of this field, to achieve national recognition through the license to practice TM. The regional pharmacist receives from the nurses all the traditional healer’s records and forwards them to the Minister of Health through a hierarchical way. Thereafter, he receives the different responses, positive or negative, and gives the document (license) to the happy recipients.

Nurses

For most of them, it was the first time to have this kind of close collaboration with traditional healers. They were satisfied with this experience since they acquired training particularly about the licensing process. The fact of referring patients to them before traditional healers’ treatment was seen as a positive point. The difficulties they encountered throughout the collaboration were mainly related to the filling of the patient medical record as some parts were not fully filled.

Traditional healers

The traditional women healers were the main beneficiary of this project. However, both men and women have positively welcomed the initiative. Indeed, the idea was such that also traditional male healers participated to the licensing process. Most of them had no interactions with the CMP in the past, especially the nurse. Thus, being followed or accompanied by the nurse was positively greeted. The collaboration with the nurse made her/him feels like a real “doctor”, as recorded during the meetings. The lack of some important administrative documents, their low level of literacy and the fact that sometimes some patients refuse referral to nurse, were the main difficulties identified.

The targets to be reached through the present intervention were mainly traditional women healers. More than 30% of traditional women healers obtained the license to practice traditional medicine. The reasons behind this low rate and the fact that no traditional woman healer from the health district of Barsalogho was licensed may include (i) a poor or incomplete filling of patient’s medical records, (ii) low number of patients to be treated during the period of assessment of ethnomedical evidence process: example of a disease with low cases in the area; and (iii) absence of specific diagnostic tools at the primary health center. All these reasons may have an effect on the process of the ethnomedical evidence. Another reason related to the low rate may be due to the cumbersome or slowness of the administrative procedure and the fact that the adoption of a new organizational chart (during the period of project implementation) by the Ministry of Health led to changes resulting in delays, especially with regard to the meeting of the expert committee in charge of evaluating the applications of traditional healers.

Both women and men traditional healers are faced to the same challenges, e.g., low levels of literacy, little recognition and notoriety, lack of good information, low interactions with CMP, little or no access to financial resources. However women are more likely to encounter some of these issues compared to the men as described elsewhere (Adebo and Alfred, 2011). In this report, we noticed that regarding to their position within their association, women were somewhat under-represented in the governing body of the association. This situation may be related to the lack of self-confidence and the fact that contrary to their male counterparts, women need the support/authorization of their husbands before integrating groups or associations. Indeed, some selected women at the starting of the project later gave up since their husband refused.

To the best of our knowledge, there are few published reports related to a collaboration framework between CM and TM practitioners in Burkina Faso with the additional aim of helping traditional healers to obtain a national recognition through the license to practice TM. Moreover, these studies were mainly related to the fight against HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis (Simpore et al., 2003; Faye et al., 2010; Kaboru, 2013).

In line with the objective of being licensed, the traditional healers had to collaborate with nurses. For most of them, it was a first time they (both practitioners) have this kind of collaboration. Both practitioners were willing to cooperate and they have positively acknowledged the collaboration as they learned from each from other. These findings corroborate with other studies (Peltzer and Khoza, 2002; Kaboru, 2013; Gyasi, 2018). Nurses were satisfied with the experience, especially the reciprocal referral to assess the ethnomedical evidence.

Worldwide, the role and importance of TM into the health care system is well acknowledged. Both developed and developing countries use it though for different reasons. For instance, limitations of western medicine, side effects of chemical drugs are raised by people from urban areas in poor and developed countries while the extent use of TM mainly in rural areas was related to its accessibility, availability and cost (Payyappalli, 2010). The collaboration of CM and TM healers has been noticed and acknowledged throughout Africa with the role of the latter in the management of HIV/AIDS pandemic, especially the opportunistic infections related to AIDS (Mbwambo et al., 2007; Innocent, 2016; Moshabela et al., 2017). Conventional medicine practitioners and traditional healers are also willing to cooperate about bone setting, a traditional medical knowledge related to a traditional orthopedic practice (Amzat and Razum, 2018; Krah et al., 2018). Another important field where an effective reciprocal referral can be seen or expected between these two kinds of care is the management of malaria as well as mental and neurological disorders (Graz et al., 2011; Flint, 2015; Bitta et al., 2019).

The main limit of this report is the lack of data to compare these results to other studies/interventions realized in the region or other parts of the country. Further, geographic barriers were other limits as we were not able to reach several more areas of the province of Sanmatenga.

Improve the level of involvement of the conventional medicine practitioners

Although the country has taken recommendations and policies to highlight TM and its practitioners in order to achieve the integration of TM, one can see that the reality seems quite different on the ground. In fact, though the health staff has acknowledged the experience, some of them were not aware of the procedure to obtain license to practice TM. Thus, there is a real need to increase the level of involvement and commitment of health staff, pharmacists as well as medical doctors, towards TM. Initiatives or strategies susceptible to give them suitable training or refresher their training can be developed. Furthermore, like to other countries which have experimented or strongly recommended the inclusion of TM training program into medical school curricula (Innocent, 2016; Mwaka et al., 2018; World Health Organization, 2019), the government may highly encourage the implementation of this strategy in the country.

Promote and strengthen collaboration

Because they are the first contact one can have with a conventional health care, nurses have to be trained about TM. Their interaction or collaboration with TM healers through cross-referral has to be promoted since, both, nurses as well as traditional healers, objective is to improve the patient health well-being status. Collaborating with TM practitioners can be considered as a good point in the nurse career and it’s may participate to evaluate her/his professional career by the Ministry of Health.

Increase the trust into TM and its practitioners

A real integration of TM is an important source of benefits for its practitioners. Being recognized by the Ministry of Health through the license to practice TM, is a tool that boosts the self-confidence of the traditional healer, increases its notoriety and contributes to its empowerment. The traditional healers may be trained to recognize the symptoms of some important diseases and also to be familiar with this process of obtaining the authorization to exercise TM. Sharing of good information to peers, giving traditional healers non-formal education as well as communication and reporting training are initiatives that can be developed to sustain the momentum gained in this implementation project. Moreover, TM practitioners have to be encouraged to refer promptly severe cases of disease to CMP.

Traditional medicine practitioners can play important roles in the promotion and delivery of primary health care. National recognition participates to give more trust to the practice of TM. The results presented here demonstrated that most traditional healers and some CMP were not aware of the licensing procedure. A noteworthy point also observed was that this experience aroused a lot of enthusiasm to the extent that many others traditional healers have established contacts with the nurse of their community primary health care. Besides, recognition and acknowledgment of TM coupled with a serious research can foster the integration of TM healers. Considering the results of this experience, it is therefore required to enhance the collaboration between practitioners of TM and CM as it contributes to highlight the role of TM practitioners and strengthen the health care system.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

TM, Traditional Medicine; CM, Conventional Medicine; CMP, Conventional Medicine Practitioners.

The authors are grateful to the heads of the Institute of Research in Health Science (IRSS) for their support and advices on some technical issues during project implementation and are also thankful to the heads of the health care in Sanmatenga province for providing permission and support to the project. Finally, we would like to greet the commitment and involvement of the traditional healers, especially the president of Sanmatenga Traditional Healers’ Association, in carrying out project activities. The project received financial resources from the “Fonds Commun Genre” (N°03/2016/FCG).

REFERENCES

|

Abdullahi AA (2011). Trends and Challenges of Traditional Medicine in Africa. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines 8:115-123.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Adebo GM, Alfred SDY (2011). Gender dimension of herbal medicine's knowledge and practice in Ekiti and Ondo States, Nigeria. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research 5(8):1283-1290.

|

|

|

|

|

Agbor AM, Naidoo S (2016). A review of the role of African traditional medicine in the management of oral diseases. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines 13(2):133-142.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Amzat J, Razum O (2018). Traditional Medicine in Africa. In: Springer International Publishing AG (ed) Towards a Sociology of Health Discourse in Africa. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp. 79-91.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bitta MA, Kariuki SM, Gona J, Abubakar A, Newton CRJC (2019). Priority mental, neurological and substance use disorders in rural Kenya: Traditional health practitioners' and primary health care workers' perspectives. PLoS ONE 14:e0220034.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Burkina Faso Ministry of Health (2018). Profil sanitaire du Burkina, Module 2: Systeme de sante du Burkina Faso [Burkina Faso health profile, Module 2: Burkina Faso health system].

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Faye A, Traore AT, Wone I, Ndiaye P, Tal-Dia A (2010). Traditional healers in the fight against HIV/AIDS infection in the health district of Fada N'Gourma (Burkina Faso). Medecine tropicale: Revue Du Corps De Sante Colonial 70(1):96-97.

|

|

|

|

|

Flint A (2015). Traditional healing, biomedicine and the treatment of HIV/AIDS: contrasting south african and native American experiences. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 12(4):4321-4339.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Geest S van den (1997). Is there a role for traditional medicine in basic health services in Africa? A plea for a community perspective. Tropical Medicine and International Health 2(9):903-911.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gqaleni N, Moodley I, Kruger H, Ntuli A, McLeod H (2007). Traditional and complementary medicine care delivery. South African Health Review 2007(1):175-188.

|

|

|

|

|

Graz B, Kitua AY, Malebo HM (2011). To what extent can traditional medicine contribute a complementary or alternative solution to malaria control programmes?. Malaria Journal 10(1):1-7.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gyasi RM (2018). Unmasking the practices of nurses and intercultural health in sub-Saharan Africa: a useful way to improve health care?. Journal of Evidence-Based Integrative Medicine 23:2515690X18791124.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ijaz N, Boon H (2018). Statutory regulation of traditional medicine practitioners and practices: The need for distinct policy making guidelines. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine 24(4):307-313.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Innocent E (2016). Trends and challenges toward integration of traditional medicine in formal health-care system: historical perspectives and appraisal of education curricula in Sub-Sahara Africa. Journal of Intercultural Ethnopharmacology 5(3):312.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kaboru BB (2013). Active referral: An innovative approach to engaging traditional healthcare providers in TB control in Burkina Faso. Healthcare Policy 9(2):51.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kpobi L, Swartz L (2019). Indigenous and faith healing in Ghana: A brief examination of the formalising process and collaborative efforts with the biomedical health system. African journal of primary health care and Family Medicine 11(1):1-5.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Krah E, de Kruijf J, Ragno L (2018). Integrating traditional healers into the health care system: challenges and opportunities in rural northern Ghana. Journal of Community Health 43(1):157-163.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mahomoodally MF (2013). Traditional Medicines in Africa: An Appraisal of Ten Potent African Medicinal Plants. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Article ID 617459, 14 pages.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Maiga A (2018). La medecine traditionnelle en route vers la modernisation [Traditional medicine on the way to modernization].

View. Accessed 24 Aug 2020.

|

|

|

|

|

Mbwambo ZH, Mahunnah RLA, Kayombo EJ (2007). Traditional health practitioner and the scientist: bridging the gap in contemporary health research in Tanzania. Tanzania Journal of Health Research 9(2):115-120.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mokgobi MG (2014). Understanding traditional African healing. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance 20:24-34.

|

|

|

|

|

Moshabela M, Bukenya D, Darong G, Wamoyi J, McLean E, Skovdal M, Wringe A (2017). Traditional healers, faith healers and medical practitioners: the contribution of medical pluralism to bottlenecks along the cascade of care for HIV/AIDS in Eastern and Southern Africa. Sexually Transmitted Infections 93(S3).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mwaka AD, Tusabe G, Orach GC, Vohra S (2018). Turning a blind eye and a deaf ear to traditional and complementary medicine practice does not make it go away: a qualitative study exploring perceptions and attitudes of stakeholders towards the integration of traditional and complementary medicine into medical school curriculum in Uganda. BMC Medical Education 18:310.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ozioma E-OJ, Chinwe OAN (2019). Herbal Medicines in African Traditional Medicine. In: Herbal Medicine. Intechopen pp. 191-214.

|

|

|

|

|

Payyappalli U (2010). Role of Traditional Medicine in Primary Health Care: An Overview of Perspectives and Challenging. Yokohama Journal of Social Sciences 14:57-77.

|

|

|

|

|

Peltzer K, Khoza LB (2002). Attitudes and knowledge of nurse practitioners towards traditional healing, faith healing and complementary medicine in the Northern Province of South Africa. Curationis 25:30-40.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sambo GL (2003). Integration of traditional medicine into health systems in the African region- The journey so far. African Health Monitor 4:8-11.

|

|

|

|

|

Simpore J, Nikiema JB, Sia D (2003). Evaluation of Traditional medicines for the management of HIV/AIDS: The Experience of Burkina Faso. African Health Monitor 4:29-30.

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (2001). Legal status of traditional medicine and complementary/alternative medicine: A worldwide review. World Health Organization.

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (ed) (2013). WHO traditional medicine strategy. 2014-2023. World Health Organization, Geneva.

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (ed) (2019). WHO global report on traditional and complementary medicine, 2019. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland.

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Western Pacific (1999). Traditional and Modern Medicine : Harmonizing the Two Approaches : a Report of the Consultation Meeting on Traditional and Modern Medicine : Harmonizing the Two Approaches, Beijing, China. Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Zuma T, Wight D, Rochat T, Moshabela M (2016). The role of traditional health practitioners in Rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: generic or mode specific? BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine 16(1):1-13.

Crossref

|

|