ABSTRACT

Family planning service contributes a lot to reduction of morbidity and mortality and it does more to help couples limit the number of their children. Women’s ability to control their own fertility is strongly affected by social constructs of gender role, expectations and gender inequalities. This study aims to explore influence of femininity and masculinity on family planning decision-making among married men and women, rural Ethiopia, in 2014-15. A qualitative study involving grounded data was employed. Data collection included in-depth interviews with key informants, and focus group discussion was conducted. Axial coding was employed. The results revealed that different femininity and masculinity practices in the community were obstacles for family planning. Decision-making power of men on family planning, seeing children as social prestige due to cultural beliefs, low status of women in community, undermining of the knowledge of women, restricting the responsibility of women/wives to the home, the dominance of men/husbands on households. Thus, due to men’s dominance at the household level and other related factors, the role of women on family planning decision-making was limited to merely accepting the decisions of their husbands. Final decision was made based on the men’s interest.

Key words: Femininity, masculinity, qualitative research, family planning decision making.

Family planning (FP) service contributes not only to the reduction of morbidity and mortality of mothers and children, but also averting unplanned pregnancy and its adverse consequence, that is, high risk abortion, preventing of HIV/AIDS and other sexually transmitted diseases, improving standard of living, increasing of household income; and promoting the conservation and efficient use of natural resources (Central Statistics Agency, 2006; WHO, 2010).

Family planning does more than help women and couples limit the size of their families, it safeguards individual health and rights, preserves natural resources, and can improve the economic outlook for families and communities (Central Statistics Agency, 2006; WHO, 2010).

In sub-Saharan Africa as a whole, only 17% of married women are using contraceptives, as against 50% in North Africa and the Middle East, 39% in South Asia, 76% in East Asia and the Pacific and 68% in Latin America and the Caribbean. Only in few countries, such as South Africa, Zimbabwe, Botswana, and Kenya, have family planning programs been successful enough to increase contraceptive use to much higher levels (Population Family planning, 2004).

Family planning services were introduced in Ethiopia in 1948. Although at the beginning the services were limited to only major cities, gradually the services expanded to the rural areas and are being used now by the rural communities (FMOH, 2003).

The Government of Ethiopia is committed to achieving Millennium Development Goal 5 (MDG5), to improve maternal health, with a target of reducing the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) by three-quarters over the period 1990 to 2015. Accordingly, the Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) has applied multi-pronged approaches to reducing maternal and new born morbidity and mortality (CSA and ICF international, 2012). Adverse consequences of low provision family planning, and increase of maternal mortality due to unwanted pregnancy and illegal abortion hinders mothers from participating in developmental activities, children do not grow properly due to lack of appropriate care and affection by parents and children are exposed to illnesses and deaths due to the lack of appropriate care from parents.

Children and the rest of the family members do not receive adequate health and other social services and unfavorable impact on the economic status of a family to provide appropriate care to children’s growth and development (FMOH, 2003; CSA and ICF International, 2012).

Unequal power relations, especially in more patriarchal societies, may confound decisions about contraceptive use and childbearing. Studies in Ethiopia showed that because of the male dominance in the culture, women are often forced to bear large number of children (Oladeji, 2008; Gill and Stewar, 2012).

Despite the fact that FP services are made accessible nearly at all major urban areas in Ethiopia and in most instances at low or no cost, the decisions that lead women to use the services seem to occur within the context of their marriage, household and family setting (Dennis et al., 2002).

As studies have shown, worldwide gendered social expectations have many implications for women and men’s reproductive lives. A social norm favors male children and promoting women’s economic dependence on men. Inability to negotiate sex, condom use, or monogamy on equal terms leaves women and girls worldwide at high risk of unwanted pregnancy, illness and death from pregnancy-related causes, and sexually transmitted infections (Jane, 2006).

According to the men and gender equality policy project report, survey research with men and boys in numerous settings of African countries has shown how inequitable and rigid femininity and masculinity influence men’s practices on a wide range of issues, including contraceptive use and health seeking behaviour (International Men and Gender Equity Survey, 2009).

As shown in a study in Ethiopia, because of the male dominance in the culture, women are often forced to bear a large number of children. Better knowledge, fear of a partner’s opposition or negligence, involvement in decisions about child and economic affairs were statistically significant factors for better decision making power of women on the use of modern contraceptive methods in the rural part (Gutchamer Institute, 2010).

Attitude, beliefs and perception of men toward family planning

The finding from a study done in Kenya showed that when new clients were asked to give a single reason for their choice of specific family planning method, most reported the attitudes of their spouse or their peers (Kim et al., 2002).

Findings on what partners know about each other’s views and preferences show that there is often little communication, even within long-standing relationships.

Improving men’s understanding of their own motivations, fears and desires, their ability to broach topics relating to sexuality, and their respect for their partners’ wishes is central to improving reproductive health (Public Choice, Private Decisions, 2010) Many men are poorly informed regarding sexuality and reproduction and need guidance on how to share decision making and negotiate choices with their partners. About 10% of Kenyan married couples are using a method that requires male participation, such as condom, periodic abstinence, withdrawal, or vasectomy (Akinrinola and Sasheela, 2004).

Study design, inclusion and exclusion criteria

A qualitative study with grounded theory was employed. Whereas all married couples of reproductive age (15 – 49 years) that were living in the study area are the inclusion criteria, the exclusion criteria involves i) those divorced and widowed and ii) respondents who were severely ill and cannot provide adequate information during data collection.

Sample size and sampling techniques

Sample size

The sampling technique focuses on involving various stakeholders who can reflect the different inputs required to meet the set objective. A total of 8 Focus Group Discussions (FGDs), 4 with married men and 4 with married women were conducted. Two FGDs were conducted for each selected Kebele: one with married women and one with married men. For each FGD; 7-10 individuals were selected.

Married men: 8 to 10 married men among the selected rural Kebeles participated in FGD.

Married women: 7 to 9 married women among the selected rural Kebeles participated in FGD.

Participant selection

The researcher discussed and consulted with the different district focal personnel, as to the most efficient ways to recruit potential participants. The researcher used the recruitment guidelines that explained the procedure briefly to the participants in order to select the potential participants.

Sampling method

Purposive sampling was employed. The participants were selected on the criteria to meet the objective and research question of the study. For FGD, participants were expected to be married men/women, formal resident of the Kebele, includes ever user, current user and non-user regarding family planning status. This criterion was used for both married men and women for FGD. Key informants were selected based on the knowledge and exposure they have in relation to the topic by consulting with village leaders from their respective kebele.

Data collection process

Data collection involved using semi-structured interview guides with open-ended questions. The most common qualitative data collection techniques, both in-depth interviews and FGDs was employed and audio recorded.

Data collection method

Two most common methods of data collection in qualitative study were employed, viz; in-depth interview and focus group discussion.

In-depth interview participants

A total of 14 in-depth interviews were conducted among the selected key informants. The selected key informants for the study were: District family planning focal personnel (1), District women’s and children’s affairs (1), Health extension workers (4), Religious leaders (4) and Kebele Women’s Federation (4). The interview was conducted face-to-face and involved one interviewer and one participant which took between 35-50 min.

Data management and analysis procedure

Transcription headers with basic information about an interview participant were added to each transcript. All interview notes and audio recordings were transcribed into local language then translated to English by the principal investigator immediately after data collection.

Following the transcription, axial coding was employed. Those codes were aggregated and the concepts were defined, and memos were elaborated to the concepts developed by the researcher. Conceptualization of the data was done using the memos. To manage the overall coding and memo developing process, Software For Qualitative Research - ATLAS.ti -7 was used.

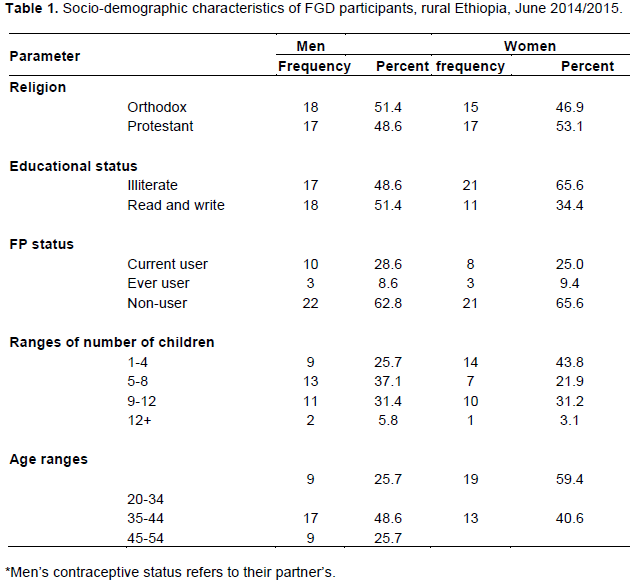

Focus group discussion participants

A total of 67 (35 men and 32 women) of the respondents participated in focus group discussions. Table 1 presents the socio-demographic characteristics of FGD participants.

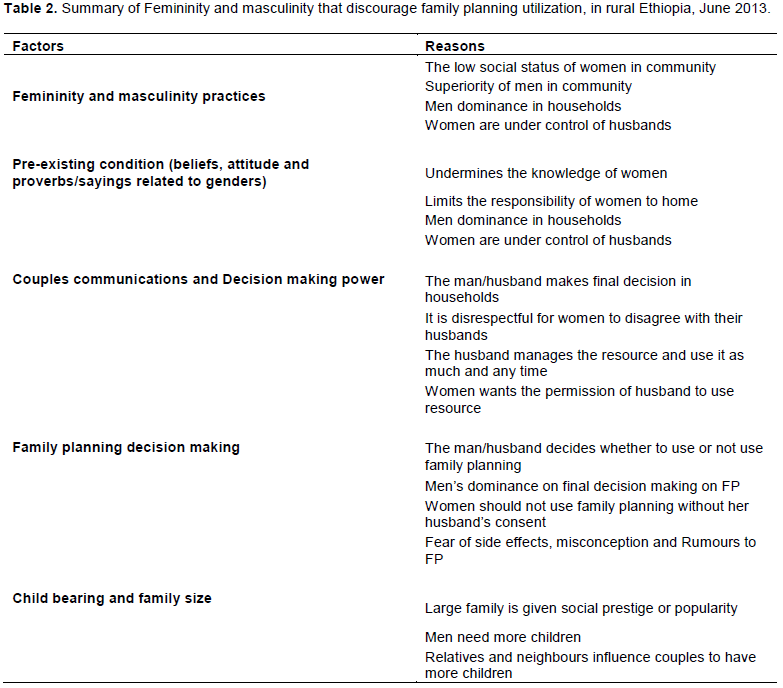

Prevalent femininity and masculinity practices

The study revealed that femininity and masculinity practice in the community begins early at birth. Cultural belief accepted from previous generation that beliefs and attitudes related to gender and lack of education was stated as the main pre-existing conditions for femininity and masculinity existing in the community. Religion did not support of femininity and masculinity. All participants said that their religion never preached the femininity and masculinity existing in the community (Table 2).

Effects of feminism and masculinity on women

Femininity and masculinity in the community lead to low social status for women. A man is the sole decision-maker, and it does not matter whether the woman has her views or not. Men want to have the first and last word on their household.

One participant said:

“…women cook, fetch water, go to the mail house, collect wood, make coffee, care for children, wash clothes, etc. In addition to all these activities, during farming session and harvest session they work on field equally with men. At night after field work men can sleep but the women hardly get any rest. They cook dinner, fetch water, make coffee, wash children, etc… They are so busy with homework up till midnight or more. Again they wake up very early before their husbands and make breakfast, coffee, fetch water, yet men will sleep and wake up when everything was ready. Women have no rest all the day.…” ( 36 yrs old Men FGD, Osole Kebele).

As stated in the quotes above, both men and women that participated in the study stated that they understood the effect of femininity and masculinity beliefs on the health of women in their community.

All household activities that are difficult and affect the health of women are believed as responsibility of women. Both men and women accept the aforementioned fact.

The quote given by District Women’s and Children’s Affairs supports this idea.

“…In rural communities, women spend most of their time at home. Women are working 17-18 h per day in our District. This shows how much burden was on each woman. She wakes up early before her husband and sleeps after midnight. Women have no time to take rest each day.” (Head, District Women’s and Children’s Affairs).

In the community, it was believed that accomplishing all household activities is the responsibility of women. Due to this belief, the community have different attitude towards the works and this leads to work division among men and women.

Pre-existing conditions that support femininity and masculinity in the community

Cultural beliefs and attitude towards gender are stated as the major factors that play a crucial role in the existence of femininity and masculinity in the community.

Participants said that different proverbs and sayings highly express different levels of femininity and masculinity in the community, facts accepted by the previous generation.

Femininity and masculinity in the community are long lasting and deeply rooted within the life of the community. Most of the participants believe that beliefs are given by God and universally accepted in the world.

The head of District Women’s and Children’s Affairs said:

“… It is common that most of the norms come from previous generations. So these are deeply rooted in the day to day life of this community. It is accepted as culture and beliefs of this community. It is rare to see cases where women complain or protest the activities of her husband.”

As stated by all participants and religious leaders of both schools of thought (the orthodox Christianity and protestant) of the Christian religion, there is no difference between men and women according to their religious views and their doctrine. One of the religious leaders said:

“… My religion is protestant and I am an evangelist. Our religious views or doctrines is that women and men are equal. That was stated in the Holy Bible… femininity and masculinity in the community are highly related with cultural beliefs and attitudes toward gender of the community…. Lack of education is also another factor. Majority of this community have no educational background and they live according to the culture and beliefs of previous generations” (Religious leader, protestant, Chanco Kebena).

Family planning decision making process

Decision on family planning between married couples is

not familiar as participants reports. District family planning focal personnel, District Women’s and Children’s Affairs and HEWs highly related the decision between married men and women with femininity and masculinity in the community.

In addition, the main problem stated by almost all participants is that there is disagreement or interest gap between the couples on family planning. One participant of FGD said:

“...Even if couples (married men and women) discuss family planning, the family decision-making is based on the interest of the husband. Most men or husbands assume they were defeated or lose acceptance if they accept the ideas of their wives. He will never be given any responsibility in community. He is considered as the one who cannot lead his house/wife. All these make men aggressive and protestors towards the interest of their wives”. (28 yrs old, Men FGD Osole Kebele)

The decision-making power of women in the community is almost null; always, women are under the control of their husbands. That norm directly plays a crucial role on the decision-making process on family planning among the couples.

Cultural beliefs related to number of children

Men’s need for more children as social prestige, fear of side effects, misconception and rumours related with methods and lack of decision making power of women are among the most stated challenges regarding poor utilization of family planning among married men and women. Men are highly expected to get a child after being married. One male of FGD participant said that:

“…. The attitude of men toward lots of children has still not changed. Men believe that their names will be conserved by their children so they want to get many children in order to be popular in the community. They are looked at as a source of pride”. (47 yrs old Men, FGD Osole Kebele)

The above quote shows cultural belief and attitude toward children in the community regarding men/husbands. Having a child early after the marriage is what is expected from the husband.

In the community, there are cultural beliefs that a family with many children has less risk of being physically attacked by another family than a family with a small number of children. One participant of FGD said:

“Let me tell you a story that I know. My grandfather is the only child of his family. He said he was attacked by the children of those from a large family (those having many brothers and sisters) and people did not respect him because he has no brothers and sisters. Then he got married and got my father and told him to have a lot of children. Then my father married four women and now he has 32 children including me. Now our family is highly respected in the community and no one wants to make any conflict with our family. In case of any problem we fight for each other…” (30 yrs old Men, FGD Tullu Gurji Kebele).

Some participants both men and women stated that the need for more children is not only desired by men, but also there are women who want to have more children as well.

Final decision-making on FP and role of women

In the community, final decision on family planning was made by the husband. Only few couples were deciding the method by discussion.

If women/wives are against the interest of their husband they will be divorced or the men go to other women to get children. Once the women were divorced it is impossible or very difficult for them to get married again. But men can marry other women without any difficulty at any time. One participant said that:

“The husband is the final decision maker.… If his wife refused he does not care about her. In our community, the divorced women are not respected and other men also are not interested to marry them. So, though the wife is not interested to have more children, due to fear of being divorced, she is forced to fulfil the interest of her husband” (35 yrs old Men, FGD, Tullu Gurji Kebele).

Using family planning in secret and consequences

The extent of using family planning in secret is high and common among married women in the community. The main reason for the women using the selected method in secret was due to their husbands possible rejection of their opinion of using family planning.

One participant of FGD said that:

“It is common. The number of women using FP in secret is not a small number if you compare it with those who use it formally. The main reason for this is that husbands never want their wives to use family planning. It is assumed as a duty for the wife to give birth.”(34 yrs old Men, FGD Osole kebele).

As for those women who use family planning in secret, Depo Provera Injection was their method of choice.

Family planning decision-making, femininity and masculinity

In the community, there are different norms related directly with gender. The ways women grow up in their family has great impact on their decision-making power. From their early childhood, daughters are commanded to accept what was said by their father and brothers. Also, they are not permitted to go out of the home and are protected against speaking in front of men.

Family planning decision-making process between married men and women was directly related with those femininity and masculinity. Women believe that they must obey what was said by their husband. One FGD participant said:

“Yes of course. As we discussed before women cannot do what they want as men do. If she wants to quit or space a birth it must also be the interest of her husband. Unless it is in the interest of the husband, it is impossible for women to use family planning. This is due to the fact that women are under the control of their husbands (40 yrs old Men, Chanco Kebele).

From the study, it was found that beyond the complexity of femininity and masculinity in the community they put men/husbands and women/wives in opposite direction. This means that there are attitudes and beliefs about both genders in the community that will always pitch them as opposite to each other. What was permitted for men is forbidden for women and the vice-versa. It is obvious that the femininity and masculinity in the community were very complicated and influenced by different factors. So, this was used to make the conceptualization shown in Figure 1 less complicated and easy to understand.

The conceptualization was made from two views; first, femininity and masculinity on the side of men/husbands’ identity (masculinity); and second were on side of women/wives’ (femininity) identity in the community. Figure 2 depicts the suggested conceptualization.

The aim of this study was to explore femininity and masculinity influence on family planning decision-making among married men and women in rural kebeles of Ethiopia. With this broad question, the purpose was to identify what men’s identity (masculinity) means for men and women’s identity (femininity) means for women, what are the pre-existing conditions for the existence of those femininity and masculinity, how femininity and masculinity influence the couple’s communications and decision-making power, and that childbearing and family size was the main purpose for this study.

As early as the birth date, and at family level, the ways

of expressing happiness when parents got a son and a daughter were very different. At that time (time of birth), the main issue was the sex of new born baby. Such thoughts in the community play crucial role for the development of femininity and masculinity (masculinity and femininity) identity.

Related with cultural beliefs, men are expected to have large families which were considered social prestige or popularity in the community. That is why sons are more preferred by the community than daughters.

The findings indicate that different femininity and masculinity influence FP use in various ways. Some studies emphasize the importance of influence from men/husbands and that in order to get a man’s/husband’s acceptance of FP use there is a need of better communication between partners (Berhane et al., 2010).

However, this study revealed that when a couple could not reach an agreement in relation to FP use, the husband’s decision tended to be prioritized because of a gender-based power imbalance/men’s decision-making power. A case study regarding femininity and masculinity as well as decision-making in Tanzania reports a similar situation in which almost all men and women discussed family planning, but a gender inequality was still present in the execution of decisions with family planning; the final decision maker being the male (Schuler et al., 2011).

Moreover, men are in many cases found to be more pronatalist than women, which is considered an obstacle to contraceptive use (Moser, 2001). In such cases, the power imbalance between genders will to a large extent prevent women from using contraceptives. However, a power imbalance between genders can also cause other trends. A study from Tanzania, reported that men forced their wives to use contraceptives (Oyediran et al., 2006). This may occur when the idea of family planning is becoming increasingly accepted.

These two different approaches are apparently contradictive; however, they are both a product of a common gender-imbalanced relationship as well as a tendency of a change of views on the acceptance of contraceptives. This finding also showed that there is an example of husband that made his wife use FP, even if the wife does not want to use it, but where the gender-imbalanced/decision-making power of men relationship made it difficult for this wife to refuse.

This study also found that femininity and masculinity influence opportunity of women to get information on family planning. This took place through different beliefs in the community about the role of women, for instance, women should stay at home and work, consequently hindering women from attending the meetings conducted by Kebele women federations and Health Extension workers/ HEWs. There were also examples of social sanctions such as people talking negatively about the women who attended the meetings.

Greene and Biddlecom (1997) found that significant proportions of study participants in Nigeria reported couple communication on Reproductive Health (RH) issues and concluded that this was a sign of an emerging egalitarian society where equity and respect are becoming norms. But the finding of this study found that couple communication on RH issue and family planning was not common among married men and women.

Even though husband and wife communicate on different issues of their life, no emphasis was given for RH issue and family planning. In many countries, traditional male and female gender roles deter couples from discussing sexual matters which ultimately contribute to poor reproductive health among both men and women (Hull, 2000). This study also found that in the community, the fact that women communicate on Reproductive Health (RH) issue with men was considered as shame.

The study clearly shows that fears of side effects related to the use of FP methods prevented people from using them. The interviews revealed many mis-conceptions and rumours related to side effects of FP methods, regardless of whether people had ever used FP methods or not. Many women did not intend to use the FP methods due to the aforementioned factors. On the other hand, the husbands also prevented their wives from using the methods due to those factors like fear of side effects on women, misconceptions and rumours about the methods.

From the study it was seen that femininity and masculinity (masculinity and femininity) identity have an influence on family planning decision-making among married men and women. Due to men’s dominance in households, they have the power for final decision-making on family planning matters. Due to the fact that men need more children due to cultural beliefs that children are considered social prestige, it is very difficult for women to use family planning when they intended to use it. It is only possible for married women/wives to use family planning when they got consent of their husbands.

In many developing African countries, men are often the primary decision-makers about sexual activity, reproductive, fertility, and contraceptive use (Hollerbach, 2001), which was similar with the finding of this study.

The finding of the study shows that beyond its advantage, secret use of family planning by the women/ wives has serious consequence on the life of households, especially on women. The consequence starts with a warning and ends up with divorce. Also, different physical injury may happen to women while they are torched by their husbands.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Most cultural beliefs, attitude toward gender, proverbs/ sayings related with gender are identified as pre-existing conditions for the existence of those femininity and masculinity. From this study, religion was found to have no role in the existence of femininity and masculinity in the community.

The study shows that different femininity and masculinity beliefs in the community were the main obstacles for family planning. These femininities and masculinities in communities directly or indirectly complemented each other, they become barriers of FP utilizations. Decision-making power of men/husbands on family planning is manifested in many ways including needing men’sconsent by women/wives, seeing children as social prestige due to cultural beliefs, low status of women in community, undermining knowledge of women, limiting responsibility of women/wives to home, and dominance of men/husbands on households.

The result of this study shows that all the afore-mentioned elements are intricately related with one another; subsequently, family planning decision-making among married men and women are affected by complex issues and leads to disagreement or cause a gap between the couples.

Due to men’s dominance at house level and other related factors, the women’s roles on family planning decision-making were limited to the acceptance of the idea by their husbands. Furthermore, due to men’s power of decision-making on family planning, decisions were final and based on their interest.

From the study, the couple’s communication on the issue of RH and family planning was not common even though they communicate about other issues of their life. So no consideration was given for RH and FP.

The findings of this study show that the issues of femininity and masculinity were not given emphasis in the community. Furthermore, since it was highly deep rooted with daily life of the community awareness which has no sustainability and only done by District women’s and children affairs, it did not bring change to the community.

This study also shows that even if there were some changes in the community related to a certain degree of awareness created through District women’s and children affairs on women’s right or equality, still those identified femininity and masculinity are highly exercised in daily life of the community.

Recommendations

Femininity and masculinity are highly grounded and deeply rooted in everyday life of the community. Changes related to this issue may only occur over a long period of time. Interventions should be making a sustainable effort to initiate awareness creation, discussion with community, even at the individual level. Men need to give the opportunity, in a free and safe forum, to talk about their roles as men in the community and the household level, and the stress caused on women/wives and at the same time address possible solutions to those gender related problems on family planning decision-making.

Family planning awareness messages and intervention should consider femininity and masculinity. Engaging both men and women and encouraging equitable decision-making is a must. The BCC and IEC programs targeting family planning must be encouraged at different levels of the government and policy-making and should give consideration and attention to the femininity and masculinity issues in the community.

The approach to data collection methods using face-to –face interviews and applying FGD techniques may add certain repsondents’ bias to the collected data.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Berhane A, Biadgilign, Amberbir, Morankar, Deribe (2010). Family planning utilization among rural community, Southern Ethiopia.

|

|

|

|

Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] and ORC Macro (2006). Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2005. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Calverton, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency and ORC Macro, 2.

|

|

|

|

|

Central Statistical Agency (CSA) and ICF International (2012). Ethiopia Demographic and Health, Survey 2011. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Calverton, MD, USA: CSA and ICF International.

|

|

|

|

|

Dennis P, Betemariam B, Asefa H (2002). Household organization women's autonomy and contraceptive behavior in Southern Ethiopia. Studies in family planning 30:302-314.

|

|

|

|

|

International Men and Gender Equality Survey (2009). Evolving men. Initial Results from the International Men and Gender Equality Survey, Men and gender equality policy project.

|

|

|

|

|

Federal Ministry of Health (FMOH) (2003). Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia. Family Planning Extension Package. Addis Ababa, September.

|

|

|

|

|

Greene M, Biddlecom A (1997). Absent and Problematic Men: Demographic Accounts of Male Reproductive Roles. New York: Population Council.

|

|

|

|

|

Gill R, Stewar DE (2012). Relevance of Gender-Sensitive Policies and General Health Indicators to Compare the Status of South Asian Women's Health.: women's Health Issues 2011 21(1):12-18.

|

|

|

|

|

Guttmacher Institute and International Planned Parenthood Federation (2010). Facts on Satisfying the Need for Contraception in Developing Countries. New York: Guttmacher Institute.

|

|

|

|

|

Hollerbach P (2001). Powers in families, communication and fertility decision-making. Population and Environment 3(2):146-171.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hull T (2000). Fertility Regulation and Institutional Influences. Cultural influence on fertility decision styles. Determinants of Fertility in Developing Countries. New York.

|

|

|

|

|

Jane C (2006). Interventions linking gender relations and violence with reproductive health and HIV: rationale, effectiveness and gaps.

|

|

|

|

|

Kim Y, Kols A, Mudieke S (2002). Informed choice and decision-making in family planning counseling in Kenya. International Family Planning Perspectives 24(1):4-11.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Moser RM (2001). Reproductive health issue for refugees in Latin America. Personal Communication, April 22.

|

|

|

|

|

Oladeji D (2008). Socio-cultural and norms factors influencing family planning choices among couples in Ibadan metropolis, Nigeria. Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, Nigeria.

|

|

|

|

|

Oyediran K, Isiugo-Abanihe, Uche C, Bankole A (2006). Correlates of spousal communication on fertility and family planning among the Yoruba of Nigeria. Journal of Comparative Family Studies 37(3):41-61.

|

|

|

|

|

Population Family Planning and the Future of Africa ( 2004). World watch 2004 Published in world watch magazine. 17:5. Available at: World Watch Magazine.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Public Choices, Private Decisions (2010). Sexual and Reproductive Health and the Millennium Development Goals.

|

|

|

|

|

Schuler SR, Rottach E, Mukiri P (2011). Femininity and masculinitys and family planning Decision-making in Tanzania: A qualitative study. Journal of Public Health in Africa 2(2).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (WHO) (2010). Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Population Affairs, 2010: Available At:

View

|

|