ABSTRACT

This paper examines awareness of groundwater formal and informal institutions among water users. The paper adopted sequential exploratory research design to collect quantitative and qualitative data. The sample size was 90 groundwater users, and 50% were women. Descriptive statistics, Kruskal Wallis H Test and Mann Whitney U Test were used to analyze quantitative data while qualitative data were subjected to content analysis. The results show that 50% of the respondents showed average awareness of formal institutions whereas 70 and 57.7% showed high awareness of norms and values respectively. In addition, the results showed statistically significant difference on the extent of respondents’ awareness of water institutions (P=0.001) among low, medium and high categories. Furthermore, there was no significant difference on awareness of formal institutions between male and female respondents (P=0.403). The paper concludes high groundwater users’ awareness of informal institutions including norms and values than formal institutions mainly rules and regulations particularly Water Resource Management Acts. Therefore, the paper recommends endeavours to raise awareness of formal institutions at a local level because awareness of formal and informal institutions is equally important for groundwater governance.

Key words: Water users, awareness, formal institutions, informal institutions, governance, Tanzania.

Awareness of water institutions is by no means critical for water governance because it is powerful in influencing water users’ behaviour. As such, majority of Sub-Saharan African countries have undertaken transformation of water governance aspects particularly water institutions to enhance water resources management. According to Calder (2005), United Nations World Water Assessment Programme (2015) and Mosha et al. (2016), the transformation of water governance corresponds to the Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) approach that Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has adopted and which highlights decentralization principles of water management to local water users. Water institutions guide the responsible ones including groundwater users to manage water resource. To achieve the decentralization principles as suggested by the IWRM approach requires adequate information related to water governance among water users including groundwater users. Groundwater users are those resource beneficiaries for different uses including domestic and irrigation use. According to Adhikari and Tarkowski (2013), lack of knowledge and awareness pertaining to water institutions makes it difficult for water stakeholders to participate meaningfully in the water governance. In Tanzania, the government acknowledges the importance of both formal and informal water institutions in influencing individuals’ behaviour for water resources governance. Water governance, both surface and groundwater, is guided by the National Water Policy (NAWAPO) of 2002 and the Water Resource Management Acts (WRMA) no 11 and 12 of 2009, Water Supply and Sanitation Act of 2009 together with informal institutions including norms, values and beliefs (Maganga, 2002; Sokile and Van Koppen, 2003; Kabote and John, 2017).

The National Water Policy and WRMA, in the country, emphasize water users’ participation in water resource governance. Among other things, this paper emphasizes that water users can participate effectively in water resource governance if they are aware about water institutions responsible for governing water resource. To that effect, understanding groundwater users’ awareness of water institutions is imperative to inform water management agencies including policy makers and water governance structures about the efficiency of decentralization particularly in raising awareness of water institutions related to water management at the possible lowest level. Some scholars define water institutions - adopted in this paper - as the underlying practices that purposefully shape and control human behaviour in usage and management of water resource (Merrey and Cook, 2012). These are shared social guidelines for governance structures and stakeholders on how, when, to whom, why, and where the resource should be managed, accessed and utilized. While the concept of awareness can be defined differently, it is taken in this paper to mean, having knowledge or perception of groundwater institutions. Some previous studies including Pavelic (2010) and Ngailo et al. (2016) report general awareness of water users regarding water institutions. As such, there is dearth information about the extent of awareness of water institutions among groundwater users. This paper bridges this gap by addressing the following questions:

(1) To what extent groundwater users are aware of the groundwater related institutions?

(2) What is the difference, on the extent of awareness of groundwater institutions, between male and female respondents?

Understanding the extent of awareness of groundwater users about groundwater institutions is necessary to enhance groundwater governance. This is because; it reflects the potentiality of water institutions in influencing water users’ behaviour to govern water resource. This paper is structured into five major parts. The first part introduces the paper. Part two presents methodology used while part three presents the results that are further discussed in part four. The last part presents conclusion and recommendations.

The study area

The study was conducted in Mbarali District, Mbeya Region. Mbarali is one of the districts that are found in semi-arid environment in Tanzania. The reason for selecting the district for the study is that it is essential for two things: first, paddy production and a source of water for Ruaha Great River that serves water to Ruaha National Park ecology. Second, the River is a source of water for Mtera, Kidatu and Kihansi hydroelectric power plants. All these activities depend on surface water that is dwindling as such the use of groundwater for socio-economic activities like domestic and irrigation is promoted to help sustain water in the Ruaha Great River. The district covers an area of 16,632 square kilometres and has a population of 300,517 (United Republic of Tanzania, 2014). It is located at latitude: 8° 51' (8.85°) South, longitude: 33° 51' (33.85°) East. Altitude is almost low ranging from 1000 to 1800 meters above sea level (Kangalawe et al., 2012). The minimum temperature is 19°C (June-July) while the maximum is 35° C (August to December) (Kangalawe et al., 2012). Administratively, the district is divided into 20 wards with a total of 99 villages (Figure 1). The main soil characteristics in Mbarali District are dark grey and prismatic cracking clays. Water resources, in the district, including groundwater are laid in the Great Ruaha River Catchment, which is one of the four sub-basins of the Rufiji River Basin in the country. The average rainfall is 600 mm (450-750 mm) per year, which falls between December and April and hence the district is vulnerable to water scarcity (Kayombo, 2016; Sirima, 2016). This explains the prevalence and high prominence of groundwater use, which is extracted from shallow-wells and boreholes (Pavelic et al., 2012).

The study adopted sequential exploratory research design with two phases. In the first phase, qualitative data were collected and analysed, and the results were used to refine questions in the questionnaire for the next phase of data collection that employed a household survey. To collect qualitative data, the study used Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) and key informant interviews guided by checklist of items. Quantitative data were collected through household survey using a structured questionnaire (Appendix 1). The questionnaire had two sections. Section one meant to collect demographic and socio-economic characteristics of respondents while section two helped to collect data on the extent of awareness of formal and informal water institutions. The study population was groundwater users for domestic use and sampling techniques involved purposive selection of three villages out of 99. Nyeregete, Ubaruku and Mwaluma villages were selected for the study. The selected villages represent some areas for the Groundwater Futures in Sub-Saharan Africa (Grofutures) Project, and this study is a part of the project. The Grofutures Project is a four years research project (2015 to 2018) funded by the government of the United Kingdom. The villages were chosen purposively since they have considerable groundwater interventions in Tanzania. Simple random sampling was used to select the respondents. In each village, 30 water users were randomly selected making a sample size of 90 water users. According to Bailey (1994), this sample size is appropriate because it allows statistical analysis leading to reasonable conclusions.

One Focus Group Discussion (FGD) was conducted in each village for qualitative data collection. The study used sex as a criterion to select FGDs participants in order to understand whether there were differences in awareness of water institutions by sex. Each FGD comprised of 8 to 12 participants. The proportion of women and male participants per group ranged from 5 to 7. Females were involved in the FGDs because they are responsible to fetch water for domestic uses and therefore they are likely to be aware about water institutions that govern water resource use and management. The information gathered during FGDs captured groundwater users’ awareness on groundwater formal and informal institutions. Formal institutions refer to rules, by-laws and regulations that are normally written to guide water resource governance in society. They are established and communicated through channels that are widely accepted as official. Informal institutions on the other hand, are socially shared rules, usually unwritten, that are created, communicated, and enforced outside of officially sanctioned channels. They include norms and values. Norms refer to what is right or not right, while values are principles or standards of behaviour in society. The Village Executive Officers (VEOs) from each village and the chairperson and secretary of Ubaruku Mpakani (UBAMPA) were involved as key informants.

UBAMPA is a Community Water Supply Organization (COWSO) that serves two villages in the study area. The key informant interviews were conducted to obtain information about the mechanism used to inform groundwater users on water institutions. They were selected based on the fact that they are responsible to ensure that water institutions within their localities are clearly understood and observed by the water users. In addition, household survey guided by a questionnaire was used to collect quantitative data on demographic characteristics and respondents’ awareness of formal and informal institutions. Informal institutions studied were mainly norms and values. About measurement of variables and data analysis, content analysis was employed to analyze qualitative data whereby field data were summarized based on objectives of the study. Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) was used to analyze quantitative data by computing descriptive statistics to obtain percentage distribution of the responses. (IBM Corp, 2011). A Summated Index Scale (Table 1) was used to measure the extent of awareness of water institutions among respondents. A total of 15 statements were used to measure the extent of awareness both for formal institutions, norms and values. Each respondent was asked to respond whether he/she strongly disagreed (1 score), disagreed (2 scores), neutral (3 scores), agreed (4 scores) or strongly agreed (5 scores) on each item of the scale. The median was used as cut-off point between low, medium and high extent of awareness. The scores below the median represented low extent of awareness, the median represented medium and the scores above the median represented high extent of awareness of water institutions.

Overall, 6 to 20 scores represented low awareness, 21 scores represented medium and 22 to 30 represented high awareness of formal institutions. Additionally, 4 to 17 scores represented low extent of awareness of norms, 18 scores represented medium and 19 to 20 scores represented high awareness of norms. Furthermore, 5 to 11 scores represented low awareness of values, 11.50 scores represented medium and 12 to 25 scores represented high extent of awareness of values (Table1). Reliability analysis was computed to ascertain internal consistence of the scale. In this study, awareness of groundwater institutions showed acceptable internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.704 (Table 1). According to George and Mallery (2003), an alpha value of 0.7 and above is acceptable. Cross tabulation was used to compare the extent of awareness between the villages. The Kruskal Wallis H Test was used to determine whether there were statistically significant differences on level of awareness between three categories: low, medium and high awareness. This is a non-parametric statistic useful for determining significant differences between more than two independent groups for an ordinal dependent variable (Pallant, 2007). The Mann Whitney U test was used to compare the median differences between the overall extent of male and female awareness of water formal institutions, norms and values. The test is useful to assess statistically significant differences for ordinal dependent variable by a single dichotomous independent variable (Pallant, 2007).

Respondents’ characteristics

Table 2 summarizes respondents’ characteristics. It is clear that 50% of the respondents were females. This is because the study planned to capture male and females’ awareness. The results also show that 58.9 and 33.3% of the respondents were household heads and spouses respectively. The rest were other household members. The results further show that 62.2% of the respondents depended on farming activities as their main source of income followed by 18.9% who depended on small scale businesses. This implies that majority of the respondents were smallholder farmers. According to Lwoga et al. (2011) and United Republic of Tanzania (URT) and UNDP (2015), about 70% of the Tanzania work force depends on agricultural sector for the livelihoods (Table 2). The results also show that 72.2% of the respondents were married. In addition, 80 and 64.4% were married male and female respectively. With regard to the respondents’ education level, 53.3% of the respondents held primary education (Table 3). This implies that the majority had acquired basic education. Education is a major means of providing individuals with opportunity to achieve their full potential. This involves the ability of acquiring knowledge, skills, values and attitudes needed for various social and economic roles, as well as for their all-around personal development (United Republic of Tanzania , 2000). Low education may constrain the extent of awareness of groundwater users, particularly formal institutions because they are sometimes in written form. For someone to read and understand groundwater formal institutions properly, require formal education. Table 4 shows respondents’ age, household size, total number of years a household resided in the village and household annual income.

The results show that the mean age of the respondents was 43 years. This implies that majority of the respondents were young adults who are expected to have high awareness of water institutions in order to manage water resource. Furthermore, the results show that the mean number of persons per household was 5.9. This number is above 4.9 persons reported at the national level (United Republic of Tanzania, 2012). With regard to the total number of years in which respondents resided in the village; the results show that the mean was 18.4 years. Therefore, the majority had resided enough time in the villages to be able to make sense of the formal and informal institutions for groundwater governance. The results also show that the mean annual income of the households was Tanzania Shillings (TZS) 3 074 500, equivalent to TZS 256 208 per month per household (Table 4). This amount is higher than the mean income at a national level. Literature shows that the mean household income is TZS 146 000 per month per household in Tanzania (URT, 2012). The higher household income in the study area compared to the national level can be associated with potential socio-economic activities especially paddy crop grown in the Usangu plain within Mbarali District (Ngailo et al., 2016).

Awareness of groundwater institutions

As defined in the research design section in this paper, formal institutions refer to rules and regulations that are normally written to guide water resource governance. Combining the columns for strongly disagree and disagree in Table 5, the results show that 71% of the respondents were not aware of the regulations that require all groundwater wells to be registered by the water basin authority. The same columns also show that 61% of the respondents were not aware of water regulation that directs groundwater users to protect wells from pollution. Furthermore, the results show that 61, 55.5, 49.9 and 44.4% of the respondents were not Table 6 presents respondents awareness of norms related to the groundwater governance. The results show that 95.4, 89.9, 92.2 and 95.4% of the respondents were informed on water charges, penalizing those who breach water rules, local community participation and women active participation on water management regulations respectively.informed on the restriction of washing buckets or any other object at the water point, pouring water on the ground at the water point, passing animals around water point and conducting human activities near water point respectively. The awareness of respondents on values related to groundwater governance is summarized in Table 7. The results show that 93.3, 94.4, 91, 95.5 and 95.5% of the respondents were aware about the importance of groundwater community based management, women participation on groundwater decision making, equal access to groundwater resource, mutual respect among groundwater users at the water point and sanitation at water point respectively.

Extent of awareness of groundwater institutions

The overall awareness of groundwater users on formal institutions is shown in Figure 2. Looking at the percentage of the medium category, the results show that 50% followed by 28.9% of the respondents had a medium and low awareness of formal institutions respectively. However, there were differences with regard to extent of awareness by villages (Figure 2). Furthermore, the results show that the existence of water institutions varied among villages. In some villages, both formal and informal institutions were practiced while in others only informal institutions existed. For instance, based on FGDs and key informant interviews conducted in Ubaruku village; the following formal institutions were operating: paying water charges, women participation on groundwater management decision making, restriction of using an offensive language among water users at the groundwater points, local community participation on groundwater management decision making and protection against pollution at the groundwater points. The results also show similarity of informal institutions to all villages. For instance, across the villages, there were restrictions to community members to conduct human activities near water points, passing animals at the water points, and washing buckets or objects at water points. Through direct observation, some villages particularly Nyeregete had shallow wells while in Ubaruku and Mwaluma villages there were both boreholes and shallow wells.

The boreholes in the Ubaruku village were under control of the Community Water Supply Organization (COWSO) known as UBAMPA. This was registered at a district level. In some villages, boreholes were not registered. Common to all villages is that all shallow wells were not registered. Quantitative results were in line with qualitative results. For example, during key informant interviews, it was reported that there were no directives from the water basin or district level that orient groundwater users to the institutions related to groundwater governance. For instance, a key informant in one of the villages reported that:

“I have been working here as a Village Executive Officer for more than five years, but I have never received or found any document or directives that stipulate how to govern groundwater. Thus, we have our own norms and values that guide us on how to manage groundwater resource.”

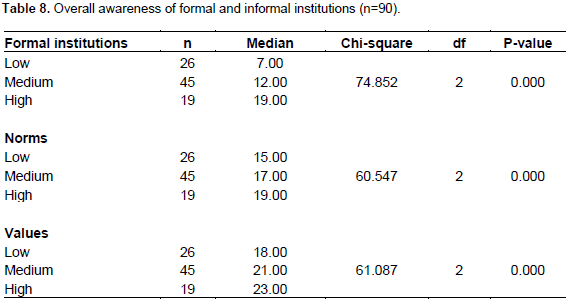

This implies that formal institutions related to groundwater resource were not well understood at the lowest level of groundwater stakeholders. The results further show that, overall, 70% of the respondents showed high extent of awareness on the established norms for groundwater governance in the respective villages (Figure 3). Water norms are restrictions developed by a particular group of people, in this case groundwater users, to enhance water resource governance. Knowing the existing norms is a step among individuals in abiding to the institutions. The overall respondents’ awareness of the values related to groundwater governance is presented in Figure 4. The results show that, overall, about half of the respondents showed high awareness of groundwater related values, followed by 41.1% of the respondents who showed medium awareness. However, there was a difference in the extent of awareness on groundwater values between villages. For instance, in Ubaruku village, 63.3% of the respondents showed high awareness of groundwater values while in Mwaluma village 30% of the respondents reported high awareness. Using Kruskal Wallis H test, the results indicate that there was statistically significant difference, at 0.01% level of significance, in awareness of formal institutions between the three categories: low, medium and high awareness. Similarly, based on low, medium and high awareness, respondents’ responses of awareness of norms and values showed significant difference at 0.01% (Table 8).

Awareness by respondents’ sex

Table 9 presents male and female responses awareness.

Awareness by respondents’ sex

Table 9 presents male and female responses awareness of formal institutions, norms and values related to groundwater governance. Using the Mann Whitney U test, the results show that there was no statistical significant difference, at 5% level of significance, on the extent of awareness of formal institutions between male and female. These results were in line with qualitative data. For instance, during FGDs at Nyeregete and Mwaluma villages, it was reported that the groundwater related regulations were not shared at a community level compared to norms and values. Participants reported that:

“Sometimes in our village through different gathering such as village meetings, and at funerals, we talk of observing the established groundwater restrictions and important behaviour or practices but we don’t talk about formal rules and regulations”.

This shows that both male and female were equally not informed about formal institutions at the village level compared to informal institutions. Similarly, some key informants at Mwaluma and Nyeregete villages reported that:

“We do not have any written document for rules and regulations on water from the district level or water basin office that guides us on how to use groundwater resource”.

This indicates that there was lack of written rules and regulations from the responsible government officials about the existing formal institutions. The results also show that there was statistical significant difference, at 0.1% level of significance (Table 9), between male and female respondents on the awareness of norms and values. Female respondents were aware about groundwater values and norms than males.

This study has shown that majority of groundwater users were not well informed of formal institutions related to groundwater governance. Linking to existing literature, it is clear that most of the formal institutions for water governance in developing countries like Tanzania are stipulated through written documents including policy documents and Water Resource Management Acts IWRMAs). Even though, majority of the groundwater users, in this study, had low and medium awareness about formal institutions. The formal institutions refereed in this study are regulations and rules including a regulation that requires all groundwater wells to be registered at a water basin level; directives to protect groundwater wells against pollution; water charges; penalizing those who breach rules and regulations and women participation in managing groundwater. It is important to note that, in this study, poor awareness of the formal institutions has resulted into serious issues. For instance, shallow wells in all villages and borehole wells in some villages were not registered contrary to the directives by the Water Resource Management Acts (WRMAs) no 11 and 12 of 2009 (United Republic of Tanzania, 2009). The low awareness can be attributed to ineffectiveness of the responsible water governance structures from the village to the district level in disseminating information to groundwater users particularly rules and regulations.

This is because, even village and district level leaders were not aware about some formal institutions. Groundwater users’ low awareness is also likely to deter effectiveness of groundwater governance more generally. In addition, some scholars including Kabote and John (2017) have argued that the low awareness of water users’ about water formal institutions intensify water resources degradation that definitely affect water quality, availability and management. Although Kabote and John (2017) dealt with surface water governance, degradation can also apply to groundwater when it comes to pollution, the fact that groundwater users were unaware about a regulation to protecting groundwater wells from pollution. According to Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2015), one of the public concerns is poor awareness of governance issues. This is one of the numerous obstacles that hinder stakeholders including local communities to engage in water governance. To that effect, the IWRM intentions of governing water resource through active participation of the local community can be constrained if water users are not well informed about formal institutions (Araral and Wang, 2013). Thus, water governance structures, policy makers and implementers have to put into consideration the agenda of raising awareness to local communities about formal institutions and its importance in enhancing groundwater governance.

While groundwater users were poorly aware about formal institutions, they showed high awareness about informal institutions mainly norms and values. The norms refereed in this study include not washing at a water point; not pouring water at a water point; not passing animals at a water point and not conducting any human activity near water point. The values include mutual respect among groundwater users; water sanitation; equal access to groundwater; women participation in groundwater decision making and community base groundwater management. The high awareness of informal institutions, among groundwater users, is attributed to the fact that groundwater norms and values are developed by the groundwater users in a given locality. In fact, groundwater users are the ones who formulate and practice them as agreed. Literature shows that informal institutions particularly norms and values, like formal institutions, have great influence on water governance because they are implemented by the given society (Ndelwa, 2013). Furthermore, according to Nkonya (2006), awareness of local communities on the informal institutions increases self-confidence of participating in water management activities. Their participation process reduces the cost of water management using formal institutions. In other words, informal institutions are cost effective compared to formal institutions because formal institutions do not necessarily evolve among the water users and in most cases they are kept in writings (Maganga, 2002). As such, it is critical to capitalize on informal institutions for cost effective groundwater governance, while making use of formal institutions.

The results in this study demonstrate high extent of awareness about norms for groundwater governance. Literature including Kaize-Boshe et al. (1998) shows that underrating informal institutions including norms can constrain water governance because informal institutions are well recognized and practiced at a local level of a society. Groundwater users in the study area were advantaged because norms, everywhere, were well known. The study also demonstrates that although the majority of the groundwater users at a local level were aware of the existing values, their awareness was low in some villages. Similarly, the extent of awareness of values though was high, varied between the communities. Based on non-parametric test particularly Kruskal Wallis H test, the extent of awareness of formal and informal institutions differed significantly with regard to high, medium and low awareness at 0.1% level of significance. This difference suggests the importance of promoting formal and informal groundwater institutions at a local level. Using Mann Whitney U Test, the extent of awareness of formal institutions between male and female res-pondents was the same. This implies that understanding and knowledge of formal institutions between male and female was low for male and female respondents. Even though, female respondents showed higher awareness than male respondents with regard to informal institutions at 1% and 5% level of significance for norms and values respectively. This can be attributed to the role of women in fetching water at the water point, which, of course is a common observation in African societies dominated by patriarchy ideology. This role subjects female to understanding norms and values relative to males.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATION

The objective of this paper was to determine awareness in general and the extent of groundwater users’ awareness of water institutions in the selected communities. Based on the results and discussion of the results, the paper concludes that groundwater users, both males and females, had medium and low awareness of formal water institutions responsible for groundwater governance. Such situation highlights that the communities as the core resource beneficiaries are likely to miss confidence to participate fully in water governance. So long as, the resource is continuously extracted by the less informed majority water users on water institutions; groundwater is definitely overwhelmed by the resource users unintentionally. Also the results demonstrate that majority of respondents showed medium and low awareness of formal water institutions implies ineffectiveness of decentralization principle as stipulated in NAWAPO of 2002 and WRMAs no 11 and 12 of 2009. The paper also demonstrates that groundwater users are highly informed on informal compared to formal groundwater institutions. Women were more aware than men about informal water institutions. Based on the conclusion, the paper recommends policy makers and other water development stakeholders to enhance awareness about formal institutions to both male and female at the local level.

This study was financed by Grofuture project whereas its overall aim was to develop scientific basis and participatory management processes by which ground-water resources can be used sustainably for poverty alleviation in Sub-Saharan Africa for which the authors are thankful. The study was specifically focused to contribute knowledge to the specific objective of constructing a set of plausible and stakeholder-informed groundwater development pathways.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Araral E, Wang Y (2013). Water Governance: A Review and Second Generation Research Agenda. Water Resource Management 27:3945-3957.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Adhikari B, Tarkowski J (2013). Examining Water Governance: A New Institutional Approach. J. Geogr. Natural Disasters 3(2):1-10. S5:

|

|

|

|

Bailey KD (1994). Methods of Social Research. Free Press, New York.588 p.

|

|

|

|

Calder I (2005). Blue Revolution: Integrated Land and Water Resources Management. Earth scan, United Kingdoms.376 p.

|

|

|

|

George D, Mallery P (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. (4th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon. 123 p.

|

|

|

|

IBM Corp (2011). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 20.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

|

|

|

|

Kabote SJ, John P (2017). Water Governance in Tanzania: Performance of Governance Structures and Institutions. World J. Soc. Sci. Hum. 3:15-25.

View

|

|

|

|

Kaize-Boshe K, Kamara B, Mugabe J (1998). Biodiversity Management in Tanzania.

|

|

|

|

Kangalawe R, Mwakalila S, Masolwa P (2012). Climate change impacts, local knowledge and coping strategies in the great Ruaha river catchment area, Tanzania. Natural Resour. J. 2:212-223.

|

|

|

|

Kayombo WC (2016). Assessing meteorological data for reference evapotranspiration in Kyela and Mbarali district. J. Environ. Earth Sci. 6(4):1-7.

|

|

|

|

Lwoga ET, Stilwell C, Ngulube P (2011). Access and use of agricultural information and knowledge in Tanzania. Lib. Rev. 60(5):383-395.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Maganga FP (2002). The Interplay between formal and informal systems of managing resource conflicts: Some evidence from South Western Tanzania. European J. Dev. Res. 14(2):51-70.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Merrey DJ, Cook S (2012). Fostering institutional creativity at multiple levels: Towards facilitated institutional bricolage. Water Alternatives 5(1):1-19.

|

|

|

|

Mosha DB, Kajembe GC, Tarimo AKPR, Vedeld P, Mbeyale GE (2016). Performance of water management institutions in farmer-management Irrigation schemes in Iringa rural and Kilombero districts, Tanzania. Int. J. Asian Soc. Sci. 6(8):430-445.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ndelwa LL (2013). Role of water user associations in the management of water use conflicts: a case of Ilonga Sub-catchment in Wami-Ruvu Basin, Tanzania.

|

|

|

|

Ngailo JA, Mwakasendo JA, Kisandu DB (2016). Rice farming in the Southern highlands of Tanzania: Management practices, socio-economic roles and production constraints. Euro. J. Res. Soc. Sci. 4(3):1-13.

|

|

|

|

Nkonya LK (2006). Customary Laws for Access to and Management of Drinking Water in Tanzania.

|

|

|

|

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2015). Stakeholder Engagement for Inclusive Water Governance, OECD Studies on Water, OECD Publishing, Paris.

View

|

|

|

|

Pallant J (2007). Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) Survival Manual: A Step by Step Guide to Data Analysis Using SPSS for Windows 3rd Edition. Open University Press, Berkshire. 335 p.

|

|

|

|

Pavelic P, Giordano M, Keraita B, Ramesh V, Rao T (2012). Groundwater- availability and use in Sub-Saharan Africa: A review of countries.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Sirima A (2016). Social and economic impacts of Ruaha national park expansion. Open J. Soc. Sci. 4: 1-11.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Sokile CS, Van Koppen B (2003). Local Water Rights and Local Water User Entities: Unsung Heroines to Water Resource Management in Tanzania.

|

|

|

|

United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (2000). Education in a Global Era: Challenges to Equity, Opportunity for Diversity.

|

|

|

|

United Republic of Tanzania (URT) (2012).Water Sector Status Report. Ministry of Water, Dar-es Salaam.

|

|

|

|

United Republic of Tanzania (URT) and UNDP. (2015). Economic Transformation for Human Development: Tanzania Human Development Report 2014. Economic and Social Research Foundation. Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

|

|

|

|

United Nations World Water Assessment Programme (WWAP) (2015). The United Nations World Water Development Report: Water for a Sustainable World. Paris, UNESCO.

|