The purpose of the study is to present financial accountability mechanisms in local governments, with reference to Kabale district local government. A cross-sectional research design, which used both quantitative and qualitative approaches to collect and analyze data, was adopted. Both simple random and purposive sampling techniques were used to select 117 respondents from 174 subjects. Questionnaires and personal interviews were used to collect data from respondents. Frequencies and percentages were used to analyze quantitative data, while direct quotes from interviews conducted among key informants formed the basis for qualitative analysis. Quantitative analysis was aided by software for document analysis (SPSS V 20.0). The study found out that service delivery was the most commonly used financial accountability mechanism, followed by financial reporting, expenditure control and budget. The paper therefore, concluded that service delivery is the most used mechanism of financial accountability, though the district’s local budget seemed unclear on reflecting the priorities of the local people. This paper suggests that the local government should ensure that the district’s budget demonstrates community preference; salaries and wages should be paid in accordance with the district’s approved budget; expenditures on development should always be as per the approved budget, and the mode of financial reporting, particularly on liabilities should be standardized.

From the theoretical perspective, financial accountability was discussed in view of the Principal-agent theory. The principal, who are the citizens grant some authority to the agents (politicians and civil servants) to act on their behalf (Shah, 2007; Agwor and Akani, 2017; Gailmardy, 2012). The principal-agent theory relates the customer (principal), who pays for services or goods, and the agent. More than often, however, the agent least does what the principal expects (Hlavaeek and Hlavaeek, 2006), yet the principal is limited in his ability to monitor and judge the contractor’s input and output (Keil, 2005), which leads to mistrust and can only be avoided under high monitoring costs. In ideal situations, the public empowers government officials to promote public welfare using public resources. However, more often than none, government officials serve their own interests, which jeopardize service to the public. According to (Berner and Smith, 2004) accountability is interpreted as the ability of the principals (public) to question the conduct and behavior of the agents, and to impose sanctions where such conduct or behavior falls short of the requirement. This would be demonstrated in the ballot box on the side of the politicians, but how about the civil servants? In growing democracies, the agents override the principals, thus denying them full participation in their demand for accountability of the actions of the agents (Cabannes, 2005) to the point of denying them full participation through information exchange. Principals only disseminate information to advance their own self-interests and to maximize their own utilities (United Nations, 1999). According to Birskyte (2013), the public attempts to demand accountability from politicians and civil servants however, a wider range of principals lack the capacity to hold agents accountable. This research argues that while the public can be involved in demanding accountability from politicians and civil servants, the public is also driven by personal interests, political patronage, resource shortage and foreign backings. In turn, the agents do not consider the targets of the constituent principals. In other words, the principal-agent-theory cannot apply in dynamic situations where power is not directly delegated. As people continue to look to politicians for cash in exchange for their votes, this implies a decrease in their legality to demand accountability (United Nations, 2005). Since resources are in the hands of an elected government, people must be corrupted by accepting bribes for their votes, which constrains effectiveness and delivery of public goods.

Accountability is generally defined as accepting and meeting one's personal responsibilities, being and feeling obligated to another individual as well as oneself, and having to justify one's actions to others (Wilson et al., 2010). Accountability has frequently been presented as rational practice to ensure responsibility by individuals and institutions, which should be implemented in all civil societies, economic institutions and organizations (Agwor and Akani, 2017). He noted that the traditional tools of accountability are often considered by non-profit organizations as unnecessary formal tasks and excessive bureaucracy, which can have important consequences both organizationally and managerially. According to (Onuarah and Appah, 2012), accountability focuses on the extent to which feedback recipients perceive they are responsible for, utilizing feedback information for development. A sound system of public expenditure management needs to take into account the wider values and requirements of society. Accountability, transparency, predictability and participation are important instruments for sound budget management, but also have an intrinsic value, and are generally seen as the four pillars of good governance. If budget managers do not comply with parliament's authorizations, or if public funds are used for private purposes, it is doubtful whether either aggregate fiscal discipline or efficient resource allocation, or both, will be achieved. Financial accountability is about assuring its stakeholders regarding the use of public resources (stewardship) as well as to underpin decision-making about how to allocate scarce resources like time, personnel, space, equipment and money (Doussy and Doussy, 2014). The allocation of resources may affect the entire operation and success of an organization, which often hinges on the quality of its financial management. Thus public entities have to provide information about financial activities to its stakeholders in order to discharge financial accountability. Financial accountability is a very important component of the public sector financial management process.

Financial accountability mechanisms

Expenditure controls

There is a tendency for spending on wages and salaries, goods and services and other items of recurrent expenditure to be higher than the approved budget, and for spending on the development budget to be lower than the approved amounts. The under spending in development expenditure is mainly due to capacity limitations, weak project implementation and possibly a lack of reporting on execution of donor-funded projects (Cabannes, 2005). Overspending in the recurrent budget can be attributed to weaknesses in expenditure controls, including inadequate commitment controls. The lack of data integrity is a big issue, both for aggregate and individual budget items, thus reducing the overall quality of financial reports. Credibility in public expenditure is assessed by comparing aggregate expenditure out-turn to original approved budget, compositions of expenditure out-turn to original budget and aggregate revenue out-turn to original approved budget (PNG Government, 2015). However, Hladchenko (2016) advises that when the resource envelope allows, the government should shift its policy focus towards improving the quality of public expenditure. Such restraints normally arise from the weak budget forecast.

Annual financial reports, which are a reflection of final budget outcome, may indicate an overall level of budget execution which was in line with the initial approved budget. For example, a very small difference between original and executed budget can be explained by the supplementary budget that was adopted in-year and helped reallocate expenditure among sections (Dunleavy et al., 2006). This helps to increase the overall level of budget execution. Without this supplementary budget, most public entities operate under-execution of the budgets. Similarly, Pelizzo and Stapenhurst (2013) noted that it is possible for the recurrent budget to appear overspent while the development budget is regularly under-executed. These two items broadly compensate at the overall level. At the end of the year, departments tend to transfer lapsing funds into trust accounts, which results into a recorded increased level of budget execution even though these transfers represent no more than an accounting transaction between different government accounts (Lytvynchuk, 2014). Effective expenditure control is attained when the extent to which the composition of expenditures differs from the original approved budget is compared, and that public entities can predict the extent to which the budget is predictable, reliable and reflects the implementation of stated public policy (Pelizzo and Stapenhurst, 2013; Pillay, 2013). This suggests that documents containing a large amount of detailed information with vast accompanying narrative should be provided. In a related view, Miller (2012) adds that any discrepancies in the data for total revenues and expenditures should be presented in the documents. A lack or shortage of information on important fiscal indicators such as the debt stock, financial assets, fiscal risks and tax expenditures, in addition to a medium-term budget framework impinges on the level of financial accountability. Moreover, presenting the development budget for each agency in the same section as the current budget, and modifying the definitions of the development budget would reflect genuine capital expenditure (Shah, 2007).

Financial reporting

Financial reporting plays a major role in fulfilling government’s duty to be publicly accountable in a democratic society. Financial reporting is used in assessing accountability by comparing actual financial results with the legally adopted budget, assessing financial condition and result of operations, assisting in determining compliance with financial laws and assisting in evaluating efficiency and effectiveness (Wang, 2013). The accounting profession through oversight bodies, developed certain international rules and guidelines on how financial information is treated and communicated so that measurement and presentation are less subjective (Kumar et al., 2012). These guidelines and rules for preparing financial statements are commonly known as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), The International Accounting Standards Board (IASB), the International Accounting Standards (IASs) and International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRSs). These standards start with a conceptual framework which anchors financial reports to a set of principles such as materiality (the degree to which the transaction is big enough to matter) and verifiability (the degree to which different people agree on how to measure the transaction) (Beyer and Guttman, 2012). The standards establish which resources and obligations should be recorded as assets and liabilities, which changes in assets and liabilities should be recorded, when these changes should be recorded, how the recorded assets and liabilities and changes in them should be measured, what information should be disclosed and which financial statements should be prepared (Li, 2005). That is, the standards prescribe recording and reporting practices that are deemed to be acceptable when reporting on the financial affairs of an entity.

Today, all public institutions in Uganda are adhering to IFRSs to ensure the same understanding of the information by both the preparers and users of that information. The enforcement of accounting standards improves the quality of financial reporting (Auditor General, 2017). Unfortunately, literature recognizes that measuring the quality of financial reports like the financial statements is problematic especially because different users may perceive the usefulness of information very different from each other (Indriasari, 2008; Rabrenovic, 2009; Hladchenko, 2016). This is associated with the fact that most of the stakeholders will not have the ability or need to analyze the financial statements in detail or test the compliance with accounting standards. Therefore, concentrating on characteristics like understandability, comparability, verifiability and timeliness (Kedia and Philippon, 2003), which enhance faithfulness and representation to citizens, politicians, donors, government and NGOs; is far better. Stakeholders like CSOs and community members could be probably only interested in whether the statements are trust worthy, that no corruption took place, the budget were complied with and that the organization in question is in a position to provide value for money (Graham et al., 2006). Therefore, financial statements must be transparent and easy to understand to enable making informed decision.

While the definition of financial accounting system points to set of procedures from data recording to financial reporting in order to answer budget implementation, financial accounting system can be measured by five dimensions: the accounting of cash, the accounting procedures, cash outlays, the accounting procedures assets, the accounting procedures in cash, and the presentation of financial reports. In government however, financial accountability statements are about accounting standards, which are structured to report on the financial position reporting entity (Elliot and Elliot, 2012). This suggests that emphasis of reporting is laid on accountability dimension, presentation dimension and disclosure. As the organization processes and reviews its accounting material, a systematic approach to the identification, analysis, evaluation, endorsement and periodic review of decisions taken involving such material is provided, which spans a number of accounting areas. However, at the end of the day, the final financial statements will include amounts based on judgments, estimates and assumptions by management (South African Institute of Chartered Accountants (SAICA), 2012).

A consolidated local government financial statement is prepared annually that includes full information on revenues, expenditure and financial assets including revenue arrears. These annual statements however, do not provide a full reporting on liabilities. They do not provide any information on expenditure arrears or accounts payable (Kabale District Local Government, 2015). Under the cash accounting system the source document for accounting entries is the payment voucher coupled with the electronically generated cheque or other payment instruction. Entries are dated using the date on the payment instrument. It is important to note that auditing is a crucial component of most modernist conceptions of accountability since it legitimates the information on which formal, financial accountability rests (Shulman et al., 2013).The fundamental role of an auditor is to provide independent assurance to external users that a financial report of an entity is accurate and reliable.

Service delivery

A service is an activity or a series of activities of more or less intangible nature that normally, but not necessarily, takes place in interactions between the customer and service employees and/or systems of service providers, which are provided as solutions to customer problems (Bajo et al., 2017). Service delivery can be taken to be an outcome of performance depending on the context in which it is used (Yeo and Neal, 2004). According to (Birskyte, 2013), service can be expressed in terms of capacity to deliver desired services and from which customers get satisfaction. A service delivery gap is that gap between the established delivery standards and the actual service delivered (Goncalves, 2013). It is an inconsistency between service design/quality specifications and the actual service quality by the service delivery system. Effective engagement between citizens, service providers and elected representatives is essential to democratic service delivery.

Service delivery refers to programs or services that are provided either to the general public or to specifically targeted groups of citizens, either fully or partially using government resources. This includes services such as education and training, health care, social and community support, policing, road construction and maintenance, agricultural support, water and sanitation, and other services (Salahu, 2012). He observes that service delivery excludes those services provided on a commercial basis through public corporations. Similarly, (Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA), 2016) points out that service delivery excludes policy functions, internal administration, and purely regulatory functions undertaken by the government, although performance data for these activities may be captured for internal management purposes. It also excludes defense and national security (Agwor and Akani, 2017).

Quality of service delivery has emerged as the most significant strategy in ensuring the survival of organizations and also a fundamental route to business excellence as well as extending market share of health care organizations. Service provision that is de-linked from citizen-influence and democratic decision making is unlikely to deliver quality services for the poor (Omolaye, 2015). For meaningful contributions, the poor require the ability and capacity to ask questions and, sufficient information of their right and entitlements, service options, local and national budgets, and the systems to address when decisions are taken undemocratically or when services are of poor quality. Local governments are assumed to be performing if the projects and services meet the demands of the citizens in the local areas (Agwor and Akani, 2017).

Shah (2007) insists that service delivery has to be communicated over and over again to everyone. Employees at all levels must be aligned with a single vision of what the organization is trying to accomplish. Thus, effective internal communications is the requisite for integration and harmony in the service organizations activities and quality. Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (2016) also emphasizes that the goal of any social service organization is to improve the results of the target population in some way by providing the right type of services and by providing them in an appropriate and adequate way.

Budget

Budget is a plan of financial operation embodying an estimate of proposed expenditures for a given period of time and the proposed means of financing them. In a much more general sense, budgets may be regarded as devices to aid management in operating an organization more effectively. Governments build budgets to demonstrate compliance with laws and to communicate performance effectiveness (Wilson et al., 2010). It is worth noting that financial accounting and management accounting cannot be so neatly compartmentalized in the public sector, where management accounting refers to budgeting and control, rather than accounting solely in the service of managers. The budget is an expression of public policy and political preferences (Tsurkan et al., 2016). It is an instrument of fiscal policy on revenue and spending to achieve macroeconomic objectives. It provides benchmarks for performance measured partly by the accounting system. Given their close relationship, it is often difficult to tell where budgeting ends and accounting begins. They reinforce each other in demonstrating and discharging fiscal accountability to the government's stakeholders, who are more numerous and diverse than the owners of a firm.

Budgeting is an important mechanism for financial planning and management and, as a cyclical decision-making process, it allows for the achievement of organizational priorities and objectives through limited fiscal resources. The correct application of budgeting can contribute significantly to greater efficiency, effectiveness and accountability within any organization if a level of synergy exists between the policy direction and the fiscal framework (Berner and Smith, 2004). Being part of the control environment relating to the efficient, effective and economic utilization of resources, budgets are also an indistinguishable part of the broader planning and policy environment. Similarly, (Mikesell, 2007) expresses that a budget’s importance in a democratic setting should be aligned to both the legislative and executive management environments and emphasizes publicity, amongst others, as a core principle of any budget (Neblo et al., 2010). In essence, publicity requires budget openness and transparency during all the stages of the budgeting process, which include executive recommendation, legislative consideration and budget execution.

In budgeting, this means uniting administrators, who have information on municipal finance and budgetary processes, with their constituents, who have information on their own preferences (Kim et al., 2010). This suggests that combining of information leads not only to new information but also to new understanding. The budget measures the extent to which aggregate budget expenditure outturn reflects the amount originally approved, as defined in government budget documentation and fiscal reports (Omolaye, 2015). He notes that aggregate expenditure includes planned expenditures and those incurred as a result of exceptional events such as armed conflicts or natural disasters; and expenditures financed externally by loans or grants should be included. However, if amounts are held in suspense accounts at the end of any year that could affect the scores if included in the calculations, they can be included. The budget recognizes that it is prudent to include an amount to allow for unforeseen events in the form of a contingency vote, although this should not be so large as to undermine the credibility of the budget (Salahu, 2012). Where part of the budget is protected from spending cuts for either policy (for example, poverty reduction spending) or regulatory reasons (for example, compulsory welfare payments), this will show up as a composition variance (Berner and Smith, 2004). Assessors are requested to report on the purpose and extent of protected spending in the narrative.

Accurate revenue forecasts are a key input to the preparation of a credible budget. Revenues allow the government to finance expenditures and deliver services to its citizens. Overly optimistic revenue forecasts can lead to unjustifiably large expenditure allocations that will eventually require either a potentially disruptive in-year reduction in spending or an unplanned increase in borrowing to sustain the spending level (Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA), 2016). On the other hand, undue pessimism in the forecast can result in the proceeds of an over-realization of revenue being used for spending that has not been subjected to the scrutiny of the budget process (Mikesell, 2007). As the consequences of revenue under-realization may be more severe, especially in the short term, the criteria used to score this indicator allow comparatively more flexibility, when assessing an over-realization.

A robust classification system allows transactions to be tracked throughout the budget’s formulation, execution, and reporting cycle according to administrative unit, economic category, function/sub function, or program (Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA), 2016). The budget should be presented in a format that reflects the most important classifications. The classification should be embedded in the government’s chart of accounts (the accounting classification) to ensure that every transaction can be reported in accordance with any of the classifications used. In the same line, Tsurkan et al. (2016) argue that the budget and accounting classifications should be reliable and consistently applied, providing users with confidence that information recorded against one classification will be reflected in reports under the other classification. In view of national budgets, a set of budget supporting documents must be provided by the executive to the legislature for scrutiny and approval. These documents provide a complete picture of central government fiscal forecasts, budget proposals, and outturn of the current and previous fiscal years (Mikesell, 2007). The arrangements for providing transfers from central government to sub national governments and the timeliness of information on those transfers ought to be captured. Financial reporting by sub national governments and fiscal risks to central government from sub national governments are addressed to governments through their budgets, or through conditional (earmarked) grants to sub national governments to implement selected service delivery and expenditure responsibilities (Salahu, 2012). The overall level of grants is usually determined by policy decisions at the central government’s discretion or as part of constitutional negotiation processes. However, clear criteria for the distribution of grants among sub national governments are needed to ensure a locative transparency and medium-term predictability of funds available for planning and budgeting of expenditure programs by sub national governments (Edeme and Nkalu, 2017). He further clarifies that every fiscal transfer from central government to the relevant sub national governments should be taken into consideration.

Legislatures play a critical role in the management of public finances. As part of their budget decision-making responsibilities, legislatures approve the national budget and subsequently provide oversight as the executive implements the budget (Wilson et al., 2010). The challenge that remains with local government budgets is timeliness of reliable information provided to sub national governments on their allocations from central government for the coming year. It is crucial for sub national governments to receive information on annual allocations from central government well in advance of the completion (and preferably before commencement) of their own budget-preparation processes. Information on transfers to sub national governments’ budgets should be regulated by the central government’s annual budget calendar, which should provide for reliable information on allocations early in the cycle (Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA), 2016).

The study adopted a cross-sectional research design. This type of research design measures differences between or from among a variety of people, subjects, or phenomena rather than a process of change. Data was collected in a single interface with respondents and a report was produced. Quantitative approaches were used to collect and analyze data on financial accountability constructs (expenditure control, financial reporting, service delivery and budget). The target population included local government staff, elected leaders, and civil society leaders identified from Kabale district local government (central division, town councils, sub counties). These categories of the population were contacted because they are part of financial accountability in addition to having enough experiences on financial accountability in the district. The study comprise of a total of 174 study units, constituting 100 staff, 42 elected leaders, and 32 civil society leader. The target population was stratified into three strata that is staff, elected leaders, and civil society leaders. Proportional allocation was employed to determine the number of participants to be taken from each stratum. This resulted into taking 67 staff, 29 elected leaders, and 21 civil society leaders, which was equivalent to a sample size of 117. Purposive sampling was used to select the CAO, District chairperson, and town clerks while simple random sampling was used to select the staff, elected leaders, and civil society leaders. The CAO, District chairperson, and town clerks were purposvely selected because of their vast knowledge of public finance management and accountability expectations.Questionnaires and interview methods were used to collect primary data. The CAO, district chairperson, and town clerks were interviewed while the rest of the staff, elected leaders, and civil society leaders were served with questionnaires. A structured questionnaire with close-ended questions was designed. The items were developed from literature review. The questionnaire had two sections that is a background section and a basic section. The background section had 7 items covering background characteristics. the basic section, which was directly related to financial accountability mechanisms had four sub-sections. Expenditure control had 6 items, financial reporting had 8 items, servide delivery had 7 items while budget had 7 items. All the items on financial accountability mechanisms were scale-items, measured on a 5-point likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Collected data was sorted and entered into SPSS version 20. The software was used to help in generating percentages of counts for each item used in the questionnaire. The researcher summarized percentage data into disagreement (an aggregate of strongly disagree and disagree), agreement (an aggregate of strongly agree and agree) and ‘not sure’.

Background characteristics

Participation according to gender indicates that 78.9% were male while 21.1% were female. In respect to age distribution, 43.1% belonged to (40 - 49) years of age and constituted the majority, 27.5% belonged to (30 - 39) years, 17.4% belonged to (50 and above) years while 11.9% belonged to (20 - 29) years and constituted the least participation, which suggests that most of the participants were adults with a high degree of reasoning and maturity, which were essential in the study. Regarding their marital status, In line with marital status, 75.2% indicated to be married and were the majority, 19.3% were single while only 6 participants representing 5.5% indicated the “others” option. In terms of the highest level of education revealed that 58.7% were tertiary graduates, 24.8% were university graduates while 16.5% indicated secondary as their highest level of education. According to their experience in local government activities, 52.3% had (5 -9) years’ experience with the local government, 26.5% had not worked with the local government for more than 5 years while 21.1% had worked with the local government for 10 years and over.

Financial accountability mechanisms used in Kabale district local government.

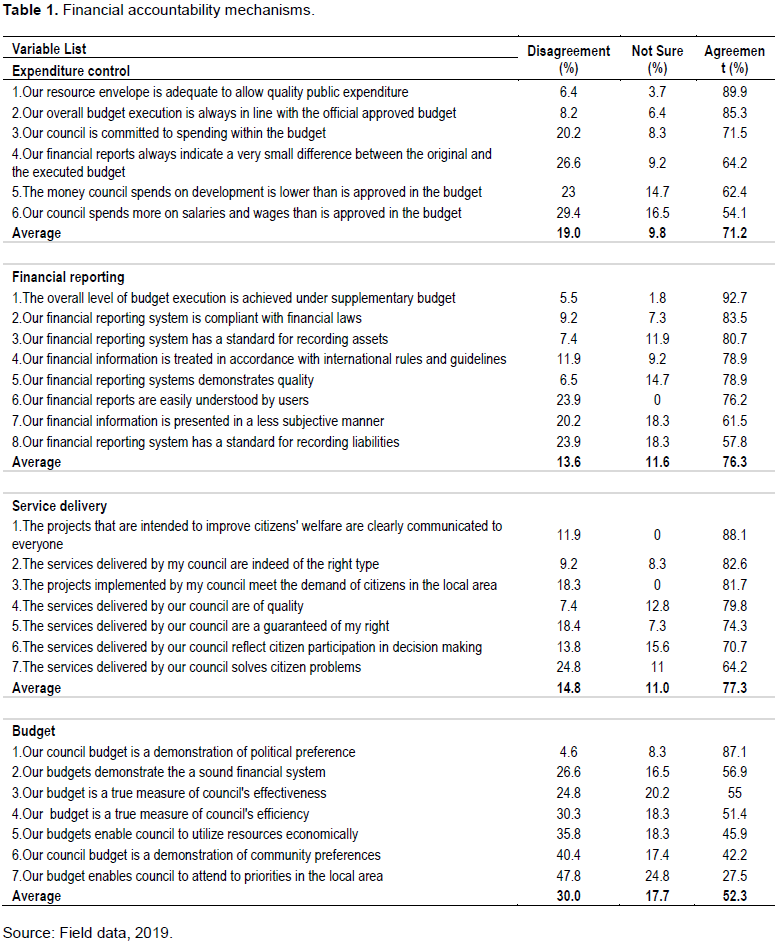

The study investigated three mechanisms of ensuring financial accountability in Kabale district local government. These were expenditure control, financial reporting, service delivery and the budget. Table 1 presents the details of the findings. Bringing to light the aspect of expenditure control as a mechanism of ensuring financial accountability in Kabale district local government, 89.9% that the district local government’s resource envelope is adequate enough to allow for quality public expenditure, while 85.3% confirmed that the district’s overall budget execution is always in line with the official approved budget and the district council is committed to spending within the budget (71.5%).

Actually, Kabale is a stop-off point for tourists to Lake Bunyonyi and the two parks famous for mountain gorilla tracking: Mgahinga national park and Bwindi impenetrable national park. In moderate presentation, 64.2% confirmed that the district’s financial reports always indicate a very small difference between the original and the expected budget, 62.4% confirmed that the money spent on development is lower than the approved budget, while 54.1% confirmed that council spends more on salaries and wages than is approved in the budget. On the whole, expenditure control as a financial accountability mechanism in Kabale district appears to stand at 71.2%.

In relation to financial reporting as a financial reporting mechanism, 92.7% confirmed that the overall budget execution is achieved under supplementary budget, 83.5% confirmed that the financial reporting system is compliant with financial laws, while 80.7% indicated that the reporting system has a standard for recording assets. In a related view, 78.9% confirmed that the local government’s financial information is treated in accordance with international rules and guidelines, which makes district’s reporting system to demonstrate quality. Though participants confirmed that their financial reports are easily understood by users (76.2%), they also moderately indicated that financial information is presented in a less subjective manner (61.5%) and that the reporting system has a standard for recording liabilities (57.8%). On the whole, financial reporting as a financial accountability in Kabale district local government appears to stand at 76.3%.

In view of service delivery, 88.1% confirmed that the district runs projects that are intended to improve citizens’ welfare, 82.6% confirmed that the services delivered by the council are indeed of the right type, 81.7% agreed that the projects implemented by the council meet the demand of citizens in the local area. About 79.8% agreed that the district delivered quality services, are a guarantee of their tight (74.3%) and reflect citizens’ participation in decision making (70.7%). On a slightly lower end, 64.2% agreed that district council solves citizen’s problems. On the whole, service delivery in Kabale district local government appears at 77.3%.

In line with budget as a mechanism of financial accountability in Kabale district local government, 87.1% indicated that budget demonstrates political preference. In moderate view points, 56.9% agreed that the budget demonstrates a sound financial system, 55.0% agreed that the budget is a true measure of council’s effectiveness while 51.4% agreed that the budget is a true measure of council’s efficiency. It should be noted that 47.8% disagreed with the view that the budget enables council to attend to priorities in the local area, 40.4% disagreed that the budget demonstrates community preference, while 35.8% disagreed that the budget enables council to utilize resources economically. The above statistics suggest a politicized and biased position on the budget as a policy document. In the same line of observation, one respondent reiterates: “…any government that delivers quality services, which are consistent with community interests and that promotes the private-sector growth alongside proper management of public resources is not far from the Millennium Development Goals…” (Civil Society Advocate). However, it remains evident that since the budget in Kabale district is a demonstration of political preference, it is true that local area priorities and preference are ignored, which renders council inefficient. Similarly, if the budget can hardly demonstrate a sound financial system, the council stands to inefficient in its utilization of economic resources. On the whole, the budget, as revealed by the statistics suggests a non-performing budget represented by 52.3%. The findings are in agreement with the opinion of one key informant: “…Mayors have the powers to implement their policy preferences but these should not suppress citizens’ interests…” (Sub County Speaker). In practice, competing interests should be analyzed democratically than politically suppressing them. It should be noted that out the four mechanisms of financial accountability used in Kabale district local government, service delivery (77.3%) and financial reporting (76.3%) appear to be two practices that propagate sound financial accountability.

The study sought to establish the financial mechanisms that are used in Kabale district local government. Participants pointed to service delivery are the most important mechanism of financial accountability in Kabale district local government. The findings are line with (MOFPED, 2017) which presented how government of Uganda has over the years introduced a number of reforms aimed at enhancing transparency, accountability of public resources and improved service delivery. The findings render support to (Rabrenovic, 2009) who outlined service delivery as one the mechanisms that can ensure sound financial accountability. Based on European Union guidelines, Rabrenovic notes that the ability of the accounting entity to remain transparent and give evidence of value for money is dependent on the effectiveness of the internal controls in place to foretell budgetary problems before they occur.

The findings seem to disagree with Auditor General (2017) whose report called for the need to ensure quality service delivery as well as citizen participation and involvement. The disagreement of the findings with Auditor general’s report comes in as corrective evidence to the recommendations of the Auditor General’s report of 2017. Contrary to Auditor General’s report, the current study presented Kabale district local government as delivering services that depict the right type and as meeting the demands of citizens. The findings is in agreement with Agwor and Akani (2017) who investigated financial accountability and performance of local governments in River State, Nigeria; and observed that local governments are assumed to be performing if the projects and services meet the demands of the citizens in the local areas.

The findings indicated pessimistically that Kabale district local government solves the problems of citizens. This agrees with Keil (2005) who analyzed the principle-agent theory and its application on outsourcing in software development. He found that the principles (who are the citizens in this case) fail to receives the goods and services they pay for because they are limited in ability to monitor and judge the input and output of the contractors (in this case the local government). Similarly, Hlavaeek and Hlavaeek (2006) who analyzed the “Principal – Agent” problem in the context of the economic survival found that the public empowers government officials to promote public welfare using public resources, however, government officials end up serving their own interests, which jeopardizes service to the public. This is true in the sense that the public lacks the ability to question the conduct and behavior of government officials and to impose sanctions where such conduct or behaviors fall short of the requirement.

The study presented the budget as the least used mechanism of financial accountability in the district. Participants disagreed that the budget enables council to attend to priorities in the local area. The findings agree with Tsurkan et al., (2016) who noted that financial accounting and management accounting cannot be neatly compartmentalized in the public sector, where management accounting refers to budgeting and control rather than accounting solely in the service of managers. Certainly, if the budget is an expression of political preference, service delivery will be compromised in favor of political interests. However, the findings disagree with Berner and Smith (2004) who view the budget as a mechanism for financial planning. In their view, the budget allows for the achievement of priorities and objectives through the limited fiscal resources. Treated in this angle, the budget can contribute significantly to greater efficiency, effectiveness and accountability within the organization. Participants also disagreed that they demonstrate community preference and that council utilizes resources economically. In this view, all public actions should embrace citizens’ preference and work towards achieving it. The findings however, disagree with Kim et al. (2010) who noted that when various stakeholders combine information on budgeting preferences, the principle of publicity overrides all the core principles of any budget. Competing interests should be analyzed and prioritized democratically.