ABSTRACT

Green Building Practices (GBPs) are gradually receiving worldwide recognition and uptake. It is argued that facilities built according to the GBPs, called green buildings are not only environmentally friendly, but also, economically more productive than other comparable ordinary ones. In the latter regard thus, green buildings’ periodical rental premiums, finished property values and energy efficiencies, amongst others, are higher. Much as these studies fare well in portraying GBPs as being environmentally sustainable, very little research has been undertaken to ascertain their economic sustainability especially in the context of Least Developed Countries (LDCs). This paper explores the latter, going through the perspectives of public awareness and access to construction finance, political will, construction industry sizes to green building materials’ sources and argues that GBPs may not be economically sustainable in the LDCs.

Key words: Green building practices, economic sustainability, climate change, environmental pollution, least developed countries.

Abbreviation:

GBPs, Green Building Practices; LDCs, Least Developed Countries; UN-HABITAT, United Nations Human Settlements Programme; UNCTAD, United Nations Conference on Trade and the Environment; UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme; UNFCCC, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; GHG, Green House Gas; USEPA, United States Environmental Protection Agency; EPBD, Energy Performance of Buildings Directive; EU, European Union; LEED, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design; WGBC, World Green Building Council; BCA, Building Construction Authority – Singapore; LCCA, Life Cycle Costing Analysis; OECD, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; CEC, Commission for Environmental Cooperation; UNECE, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe; AFDB, African Development Bank; GoM, Government of Malawi; RoZ, Republic of Zambia; RoC, Royal Kingdom of Cambodia.

In the wake of the global climate change, stakeholders have been faced with a challenge of finding means of adapting to and mitigating against the wide ranging effects of the change. Over the years, different industries, whose activities are known to contribute to or be affected by climate change, have devised strategies for adaptation and mitigation. The construction industry, which is by far the single biggest entity in contributing towards global GHG emissions, has developed GBPs (UN-HABITAT, 2010). Facilities built on these practices, known as green buildings, are said to be environmentally more sustainable than other comparable ordinary ones. In this regard, they have a considerably smaller carbon footprint.

Further to the environmental dimension, the aforesaid green buildings are also said to be economically more productive than other comparable ordinary facilities. Pursuant to the latter, these facilities yield higher periodical rental premiums, finished property values and energy efficiencies amongst others (Ellis, 2009).

GBPs largely draw their existence on studies conducted in the developed world, probably, owing to the fact that the concept is still new in the developing and least developed countries. It is worth noting at this point that research to ascertain the environmental sustainability of GBPs has been quite substantial. However, on the economic productivity, very little research has been undertaken to establish their sustainability, especially in the context of LDCs. This is in sharp contrast with the essence of sustainable development which advocates for development that optimally embraces both the environmental and socio-economic dimensions (Brundtland, 1987).

Notwithstanding the uncertainty over the economic sustainability of GBPs, there are marked differences which exist in the socio-economic conditions between the developed, developing and least developed countries. Economic responses to GBPs may not be the same in the above stated development scenarios, in which case, what may constitute a sustainable economic activity in one scenario, may not be as such in the other. Such differences necessitate the need for independent studies in each of the three scenarios. In the UNCTAD, Economic Growth in Africa report of 2012 and Dercon (2011), note that much of the discussion on green growth remains relatively vacuous in terms of specifics for poor settings, and he asks: “Is all green growth good for the poor, or do certain green growth strategies lead to unwelcome processes and even ‘green poverty’, creating societies that are greener but with higher poverty?”.

OBJECTIVES

The fundamental objective of this paper is to investigate the economic sustainability of GBPs in the context of LDCs. Using cases drawn from a number of LDCs, the paper specifically endeavours to establish the public awareness levels with regards to GBPs, public access to construction finance, availability of political will to facilitate the uptake of GBPs, the size of the construction industry and finally, sources of key green building materials.

This is a review paper. It significantly draws from reviews of literature deemed to be relevant to the afore-mentioned objectives. The study is grounded in the context of LDCs and it relies on cases randomly picked from amongst these countries.

Least Developed Countries are defined as those countries that are highly disadvantaged in their development process and facing the risk of failing to come out of poverty. According to the UNCTAD (2011), they are characterized by their low income, human assets weakness and economic vulnerability. Presently, there are 48 LDCs 70% of which are found in Sub-Saharan Africa. It has been argued that as climate change takes firmer hold, LDCs face increased vulnerability due to their heavy reliance on natural capital assets (UNEP, 2011).

Economic sustainability is defined as the maintenance of non-declining production capital stocks (Spangenberg, 2005). For the purposes of this study, economic sustainability of GBPs is determined on the basis of public awareness, access to construction finance, political will, construction industry size and the capacity to produce green building materials. The relationship between the afore-mentioned factors and the maintenance of capital stocks over time is closely examined.

GLOBAL GREEN BUILDING ADVOCACY

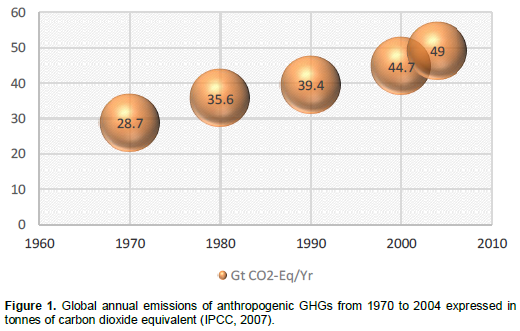

Environmental pollution, especially in the form of GHG emissions is widely believed to cause climate change (Hegerl et al., 2007). UNFCCC (2007) defines the latter as a change of climate caused directly or indirectly by human activity and observed over time. Decades of industrialisation and economic growth have seen a rise in global GHG emissions as shown in Figure 1.

Climate change has wide ranging effects on the environment and socio-economic and related sectors including water resources, agriculture and food security, human health and the built environment (UNFCCC, 2007). Conversely, the said sectors jointly contribute to the climate change cycle. The built environment does this through amongst other avenues, its massive energy consumption, currently pegged at over 30% of the global energy consumption (UNEP, 2011). Most human activities that trigger climate change are life sustaining and therefore, hard to completely abandon. The built environment activities are such kind of vital human activities. In light of this, adaptation and mitigation measures may be the only reasonable way out. Climate change adaptation measures mitigate the negative impacts of climate change (UNFCCC, 2007).

The built environment, with its oversized ecological footprint has been challenged to significantly cut on its contribution towards global GHG emissions by 2050 (UNEP, 2011). It has been pointed out as having a great potential for GHG abatement (Enkvist et al., 2007). In this regard, there has been the development of GBPs in the construction industry. GBPs are a collection of environmentally friendly measures which aim to inform an environmentally sustainable path for the Built Environment. According to the USEPA, these practices create structures and use processes that are environmentally responsible and resource-efficient throughout a building’s life-cycle from siting to design, construction, operation, maintenance, renovation and deconstruction. Such facilities emit fewer GHGs, consume less energy, use less water and offer occupants healthier environments than do typical facilities (UNEP, 2010).

On the global scene, several treaties have been signed, binding countries to commitments aimed at fostering adaptation to and mitigation against the far reaching effects of climate change (UNFCCC - Conference of Parties 17, 2011; UNFCCC, 1998). Hwang and Tan (2010) note that several governments in the developed world have enacted legislation aimed at engendering the concept of green building. They cite the EPBD, a piece of legislation that requires buildings in the EU countries to meet a minimum energy performance standard by the year 2006, the LEED standards in building construction enforced by green building legislation in the US and finally, the Building Control (Environment Sustainability) Regulations implemented in 2008 in Singapore.

As countries would like to be seen to be doing something in line with their environmental commitments in the aforesaid quest, there has been a growth in the rate of uptake of green building practices. The WGBC reports of the existence of Green Building Councils in over 80 countries around the world. This is up from just one national green building council in the United States of America in 1993. Green Building Councils are defined as member based organisations that partner with industry and government in the transformation of their buildings and communities towards sustainability (World Green Building Council). A very recent study on world green building trends by McGraw-Hill Construction, reports of an increasing rate of adoption of GBPs. The study conducted among various stake holders in the construction industry drawn from all around the world, projected that up to 60% of all construction work will be green by 2015 (McGraw Hill Construction, 2013). According to the BCA (2009a, 2011) in Hwang and Tan (2010) and Hwang and Ng (2013), the number of Green Mark certi?ed buildings in Singapore has increased from 130 in 2007 to 750 in 2011.

With such an international impetus and great force of advocacy, LDCs are bound to embrace the GBPs on a large scale, as they position themselves on the international scene. In May, 2010, the UN-Habitat organised a conference aimed at promoting green building rating systems in Africa (UN-HABITAT, 2010). The conference which was held in Nairobi, Kenya, drew participants from several least developed African countries.

GREEN BUILDING IN LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES

Generally speaking, LDCs GHG emissions are very low compared to those from DCs. Records from 1990 show that Africa, home to about 70% of the LDCs, emits just about 3.4% of the global GHG emissions (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2011).

In the wake of a rising green building consciousness internationally, there have been calls on the LDCs to adopt GBPs. It has been argued that as climate change takes firmer hold, these LDCs face increased vulnerability and need to adopt the GBPs. The increased vulnerability is on account of these countries’ heavy reliance on natural capital assets (UNEP, 2011). However, Kalua et al. (2014), note that the response in the LDCs has not been very positive and that the concept of green building remains largely under developed. The WGBC membership shows that there does not exist any established Green Building Council not even in any one of the 48 LDCs. Nonetheless, there is some evidence pointing to an enabling environment for the adoption of GBPs in the LDCs (http://www.worldgbc.org/worldgbc/become-member/members/).

Research has shown that green building costs more than conventional building in terms of capital costs. According to a study by British Research Establishment (BRE) and Cyril Sweett in (Ellis, 2009), green building generally costs between 2 and 7% more than ordinary building. An earlier estimate by Tagaza and Wilson (2004), suggested a much higher capital cost disparity pegging the green building construction cost at 25% higher than the conventional. Zhang et al. (2011) report that the higher costs may be attributed to the design complexity and the modelling costs needed to integrate green building practices into the projects. Hwang and Tan (2010) further note that the cost may also be associated with green materials and the use of green technologies. Renewable energy for instance, a green source of energy, is currently much more expensive than energy generated using fossil fuels. In the case of photovoltaic power, the ultimate price may even be far higher than for electricity from other sources (Hueting and Reijnders, 2004).

Buildings in general tend to have a long life span of use. For this reason, it is very important to extend the cost analysis of building green throughout the expected life span of the green buildings. The long term cost insight is obtained through a LCCA. For purposes of green building, LCCA is defined as an economic appraisal technique used to evaluate the economic performance of a green building throughout its life cycle comprising the initial construction, operation, maintenance and disposal (Dwaikat and Ali, 2014; Norman, 1990; Bull, 2003; Boussabaine and Kirkham, 2004; Flanagan et al., 2005; Davis, 2007b).

Some LCCA show that the higher initial capital costs for building green are largely offset by a decrease in the long term life cycle costs (World Green Building Council, 2013; Kok et al., 2012). The investment payback period in the developed world is pegged at around 3 to 5 years (World Green Building Council, 2013; Kok et al., 2012; Urban Catalyst Associates, 2005). In the developing and least developed countries such specifics remain inadequately researched. However, some literature point to a lengthy payback period for green innovations in Malawi, one of the several LDCs (Mgwadira and Gondwe, 2011).

ECONOMIC PRODUCTIVITY OF GREEN BUILDING PRACTICES

The OECD (2001) defines economic productivity as a ratio of output to a volume measure of input use. Economic productivity of GBPs may thus be crudely defined as a ratio of the finished green buildings’ value, energy efficiency in use and rental premiums, amongst other aspects to the initial investment capital.

It has already been noted earlier that in addition to being environmentally friendly, green buildings are also said to be economically more productive than other comparable ordinary facilities. Pursuant to the latter, these facilities yield higher periodical rental premiums, finished property values and energy efficiencies amongst others (UN-HABITAT, 2010; Ellis, 2009; Miller et al., 2008).

A comparative study on green and ordinary buildings conducted by Miller et al. (2008) in the United States of America, reported higher sales values and rental premiums for green-rated buildings as shown in Figure 2.

Ellis (2009), reports another study which was undertaken on an existing building to assess its energy performance before and after retrofitting it to satisfy green building criteria. The results presented in Table 1 showed that the retrofitted building was 78% more energy efficient than in its initial ordinary form.

ECONOMIC SUSTAINABILITY OF GREEN BUILDING PRACTICES

The adaptation path taken by GBPs has largely been ecological than economical (UNFCCC, 1998; CEC, 2008). Emphasis has been on reducing the built environment’s per capita contribution towards GHG emissions and the mainstream natural physical environmental degradation.

On the economic front, very little research has been undertaken to ascertain the linkages between GBPs and the economic performance of green buildings, especially in the long term for purposes of sustainability evaluation. The available literature has largely dwelt on the immediate economic benefits of building green compared to building conventionally and in the context of the developed world. Ellis (2009), reports that in addition to their environmental benefits, green facilities are also economically more productive than other comparable ordinary ones. No attempt is made at investigating the economic productivity overtime.

Economic sustainability has been a very contentious issue among Economists (Stavins et al., 2003). However, most Economists generally agree on the essence of economic sustainability as being the maintenance of the present well-being with due regard to inter temporal distributional equity, dynamic efficiency and intergenerational equity (Stavins et al., 2003). Economic sustainability thus boils down to the maintenance of non-declining production capital stocks in the form of man-made, natural and social capital (Spangenberg, 2005). It can be seen at this point that discourse on economic sustainability is made whole with the inclusion of a time factor. The economic productivity ought to be considered over a period of time.

Drawing from the definitions of sustainable development by the Brundtland Commission of 1987 (Brundtland, 1987), and economic productivity in (OECD), this paper suggests a crude definition for the economic sustainability of GBPs as the maintenance of a favourable ratio of the finished green building’s value, energy efficiency in use and rental premiums, amongst other aspects to the initial investment capital, considered over a period of time. The maintenance of non-declining capital stocks ought not to compromise on the future generations’ capacity to achieve the same.

The economic sustainability of the GBPs especially in the context of the under developed world has largely remained inconclusively researched and thus uncertain. Dercon (2011) notes this as a limitation in the discourse on green growth. In the absence of substantial research on the economic sustainability of GBPs, building green, capital intensive as it is, would carry a big economical risk, much as it has been proven to be environmentally beneficial.

Determinants of economic sustainability of green building practices

It has been pointed out that economic sustainability is evaluated basing on the criteria of the maintenance of non-declining production capital stocks (Spangenberg, 2005). The UNECE (2009) clearly classifies capital stocks into five namely financial capital including bonds and currency deposits, natural capital including land and ecosystems, produced capital including machinery and buildings, human capital in the form of an educated and healthy workforce and finally, social capital in the form of functioning social networks and institutions.

Economic sustainability of GBPs may be evaluated basing on the criteria of the maintenance of non-declining capital stocks required in the production of green buildings. For building construction purposes, and especially green building, this paper identifies a number of factors which may play a crucial role in the maintenance of non-declining capital stocks. These factors include public awareness, public access to construction finance, political will to facilitate green building practices, size of the construction industry and finally, local capacity to produce green building materials.

The paper argues that GBPs would be economically sustainable in a situation characterised by high levels of public awareness on green building practices, wider public access to construction finance, strong government’s commitment to promote green building practices, a medium-large sized construction industry and a capacity to locally manufacture key green building components.

ECONOMIC SUSTAINABILITY OF GREEN BUILDING PRACTICES IN THE LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES

Public awareness

It has already been noted that GBPs are still a relatively new concept in the LDCs. In the quest for a wider uptake of these practices, public awareness would be a crucial element. The general public ought to know the specifics about these GBPs. Awareness of these practices may significantly facilitate the desire to go green and may also influence the development of a general appreciation for green facilities amongst the general public. Korkmaz et al. (2009) note that the green building drive in the USA drew its inspiration from the rise in environmental awareness amongst the general public.

The lack of awareness may have a double faceted implication. Firstly, with limited awareness, the general public may not be willing to spend more on their building projects to make them green. This may weaken the drive towards green building as in the first place, very few people would be willing to adopt the GBPs. Secondly, lack of awareness would entail lack of appreciation for the GBPs and the value attached to green facilities. In the event that an investor pumps in substantial amounts of capital in a green facility, hoping to recover the investment through higher rental premiums, they would end up being frustrated as the public, having little or no appreciation for such green facilities would rather opt for cheaper ordinary comparable facilities. Such a situation would adversely affect the length of the investment payback period, much to the detriment of the investor.

In most of the LDCs, the literacy rate is generally low. This may crudely imply that a substantial percentage of the general public in the LDCs lacks awareness on GBPs. A quick review of educational programmes offered at various institutions in the LDCs further suggests that even amongst the literate population, knowledge of GBPs may only be limited to technocrats from the traditional built environment disciplines such as architecture, engineering and land management. This is in spite of the fact that construction work can be initiated by anyone from the whole spectrum of professional backgrounds.

Public access to construction finance

Building is a capital intensive endeavour. Notwithstanding, the high capital requirement, studies have shown that green building costs more than conventional building (Ellis, 2009). In the developed world, most private building projects rely on capital resources from lending institutions. It is estimated that over 50% of the private home owners in the UK, a developed country, rely on some form of construction finance (Coogan, 1998). This is in sharp contrast with the situation in the LDCs, where the public access to construction finance is very limited. In Malawi, for instance, the public access to construction finance is very inadequate (AFDB, 2013-2017). Manda et al. (2011), note that the borrowing conditions set by lending institutions in Malawi are very restrictive. Financing institutions demand duly registered collateral before finances can be disbursed. In a country where proprietary title registration is not only costly but also lengthy (AFDB, 2013-2017), this limits the access to the minority elitist sections of the society. A survey conducted by Finscope in Mutero (2010), reports of a similar situation in Tanzania. According to the survey, only about 5% of Tanzanians have access to formal finance of any kind.

Adequate access to construction finance may provide the production resources required for a green building project, capital intensive as that might be. On the other hand, limited access to finances would imply that there is very little or no investment capital at all. In such a scenario, any talk about sustainability would be rendered irrelevant.

Political will to facilitate green building practices

Construction work does not take place in a vacuum. Every aspect of a project is controlled by a range of legislative and administrative tools. This legislative environment largely draws its mandate from political institutions. According to Tse and Ganesan (1997), government macroeconomic policy influences construction activity. A certain amount of political goodwill for GBPs would go a long way in enhancing their economic sustainability. This goodwill could be in the form of legislation recognising GBPs and ensuring their enforcement and administrative tools such as tax waivers on green building products and speedy title registration for all green facilities.

There is some evidence suggesting the existence of some political will in most LDCs to foster environmentally friendly construction practices. This can be seen in the explicit inclusion of environmental issues in governments’ policy documents such as the MGDS and the Land Use Planning Guidelines in Malawi (GoM, 2011-2016, 2011), the Rio+20 United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development national report in RoZ (2011) and the National Sustainable Development Strategy in Cambodia RoC (2009). However, this may be seen to be largely symbolic. The governments in least developed countries are faced with a battle not only against the HIV/AIDS pandemic, but also, eradication of hunger and abject poverty (Barnett et al., 2006). In light of this, environmental management and conservation issues, especially regarding controlling the built environment’s contribution towards GHG emissions, may not be accorded priority attention knowing that the present carbon footprint of the building stock in the LDCs is very small. This leaves very little motivation for the political institutions to create an environment which is conducive to green development.

Size of the construction industry

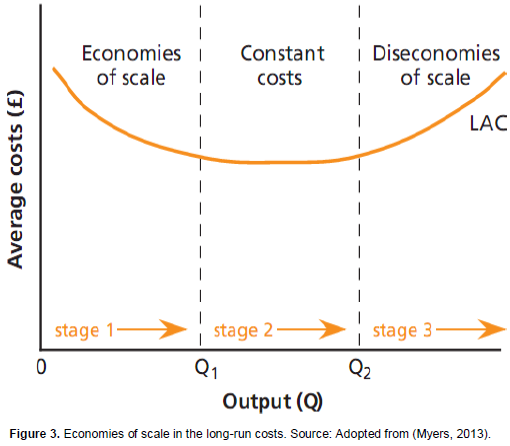

Economic theory suggests that up to a certain point in the long run, a sustained increase in production output is inversely proportional to the production cost. An investment in this phase of progression is said to be enjoying economies of scale as shown in Figure 3.

It can be seen at this point that the size of the construction industry is closely related to the exploitation of these economies of scale. According to Myers (2013), a larger construction industry provides an opportunity to buy in services easily, jointly fund research and firm specialisation amongst others. A larger construction industry with a larger market for green building products may facilitate the enjoyment of the economies of scale. This would substantially lower the green building construction cost.

The construction industry in LDCs is very small contributing just about 3 and 6.5% towards the GDP of Malawi and Nepal, respectively (Malawi Investment Promotion Agency, 2010; UN-HABITAT, 2010). In the developed world, the construction industry contributes up to 10% towards the national GDP. The small sizes of the construction industry in the LDCs may effectively limit the industry’s enjoyment of economies of scale.

Local capacity to produce green building materials

Some green building materials require elaborate technical expertise and resources to be manufactured. A country’s capacity to locally produce these materials would significantly moderate their local procurement cost. This would be a very positive stride in the economic sustainability of GBPs. On the other hand, a lack of local production facilities for these materials would raise the need for external procurement from across the borders. Such a scenario would come with a high cost implication, especially on the country’s foreign exchange reserves.

LDCs are characterised by very low industrialisation levels. The manufacturing industry remains marginally under developed, contributing less than 10% to the national GDP (UNCTAD, 2011). For this reason, these countries may have to rely on imports for the supply of key green building components. It has already been pointed out that green building may cost up to 7% more than ordinary building (Ellis, 2009). In the LDCs, this cost disparity may be even higher considering that the net construction cost must also absorb a string of import costs.

This paper concludes that GBPs may not be economically sustainable in the LDCs. The development scenario in the LDCs is one characterized by low public awareness levels with regard to GBPs, limited public access to construction finance and small sized construction industries which lack the capacity for self-sufficiency. This scenario may adversely affect the maintenance of non-declining capital stocks required in the development of green buildings.

In order to ensure the economic sustainability of GBPs in the LDCs, a number of issues need to be comprehensively addressed. To begin with, the public awareness level with regard to building green needs to be significantly raised. Secondly, it would be very important to consider the widening of public access to construction finance. In addition, the political machinery would do well to further consolidate the existing political will in favour of GBPs by enacting legislation to make green building mandatory, supporting the growth and development of the construction industry and finally, enhancing the local industrial capacity to handle green building projects.

GBPs, Green Building Practices; LDCs, Least Developed Countries; UN-HABITAT, United Nations Human Settlements Programme; UNCTAD, United Nations Conference on Trade and the Environment; UNEP, United Nations Environment Programme; UNFCCC, United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; GHG, Green House Gas; USEPA, United States Environmental Protection Agency; EPBD, Energy Performance of Buildings Directive; EU, European Union; LEED, Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design; WGBC, World Green Building Council; BCA, Building Construction Authority – Singapore; LCCA, Life Cycle Costing Analysis; OECD, Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development; CEC, Commission for Environmental Cooperation; UNECE, United Nations Economic Commission for Europe; AFDB, African Development Bank; GoM, Government of Malawi; RoZ, Republic of Zambia; RoC, Royal Kingdom of Cambodia.

REFERENCES

|

African Development Bank (AFDB) (2013-2017). Malawi Country Strategy Paper: pp. 6-7. |

|

|

|

Barnett C, Chisvo M, Kadzamira E, Meer E, Paalman M, Risner C (2006). Evaluation of DFID Country Programmes: Country Study: Malawi 2000-2005, Department for International Development. |

|

|

Boussabaine A, Kirkham R (2004). Whole Life Cycle Costing: Risk and Risk Responses. Oxford, UK, Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Crossref |

|

|

|

Brundtland GH (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future, United Nations. |

|

|

|

Building Construction Authority – BCA (2009a). 2nd Green Building Master Plan. Singapore. |

|

|

|

Building Construction Authority – BCA (2011). CDL Elevated to BCA Green Mark Platinum Champion Status. Singapore. |

|

|

|

Bull J (2003). Life Cycle Costing for Construction. Taylor & Francis. |

|

|

|

Commission for Environmental Cooperation - CEC (2008). Green Building in North America: Opportunities and Challenges, Montreal. |

|

|

|

Coogan M (1998). Recent developments in the UK housing and mortgage markets. Hous. Finan. Int. 12:3-9. |

|

|

|

Davis L (2007b). Life Cycle Costing as a Contribution to Sustainable Construction: A Common Methodology, Davis Langdon Management Consulting. |

|

|

|

Dwaikat LN, Ali KN (2014). Green Buildings' Actual Life Cycle Cost Control: A Framework for Investigation. 13th Management in Construction Research Association Conference and Annual General Meeting. International Islamic University of Malaysia. |

|

|

|

Ellis CR (2009). Who Pays for Green? The Economics of Sustainable Buildings. EMEA Res. 7:2010. |

|

|

|

Enkvist P, Nauclér T, Rosander J (2007). A cost curve for greenhouse gas reduction. McKinsey Q. 1:34. |

|

|

|

Flanagan R, Jewell C, Norman G (2005). Whole Life Appraisal for Construction. Oxford, UK, Blackwell Publishing. |

|

|

|

Government of Malawi - GoM (2011). Land Use Planning and Development Management: Draft Guidelines & Standards. Lilongwe, Malawi. |

|

|

|

Government of Malawi - GoM (2011-2016). Malawi Growth and Development Strategy. Lilongwe, Malawi. |

|

|

|

Hegerl GC, Zwiers FW, Braconnot P, Gillett NP, Luo Y, Marengo OJA, Nicholls N, Penner JE, Stott PA (2007). Understanding and attributing climate change. In 'Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change'. (Eds S. Solomon, D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, KB Averyt, M. Tignor and HL Miller.), Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK pp. 663-745. |

|

|

Hueting R, Reijnders L (2004). Broad Sustainability Contra Sustainability: The Proper Construction of Sustainability Indicators. Ecol. Econ. 50(3):249-260.

Crossref |

|

|

Hwang BG, Ng WJ (2013). Project Management Knowledge and Skills for Green Construction: Overcoming Challenges. Int. J. Project Manage. 31:272-284.

Crossref |

|

|

Hwang BG, Tan JS (2010). Green Building Project Management: Obstacles and Solutions for Sustainable Development. Sustain. Dev. 20:335-349.

Crossref |

|

|

|

IPCC (2007): Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Core Writing Team, Pachauri, R.K and Reisinger, A. (eds.)]. IPCC, Geneva, Switzerland. |

|

|

|

Kalua A, Zhan C, Chang C (2014). A Review of Green Building Advocacy in Least Developed Countries. CIB W107 International Conference, Lagos, Nigeria. |

|

|

|

Kok N, Miller N, Morris P (2012). The Economics of Green Retrofits. JOSRE 4(1). |

|

|

|

Korkmaz S, Erten D, Syal M, Potbhare V (2009). A Review of Green Building Timelines in Developed and Developing Countries. 5th International Conference on Construction in the 21st Century, Istanbul, Turkey. |

|

|

|

Malawi Investment Promotion Agency (2010). Available on www.malawi-invest.net. |

|

|

|

Manda MA, Nkhoma S, Mitlin D (2011). Understanding pro-poor housing finance in Malawi, IIED. |

|

|

|

McGraw Hill Construction (2013). World Green Building Trends, Smart Market Report. |

|

|

|

Mgwadira R, Gondwe F (2011). Renewable Energy Investment in Malawi. USAID/NARUC Workshop. Nairobi, Kenya. |

|

|

|

Miller N, Spivey J, Florance A (2008). Does Green Pay Off? J. Real Estate Portf. Manage. 14(4):385-400. |

|

|

|

Mutero J (2010). Overview of the Housing Finance Sector in Tanzania. |

|

|

|

Myers D (2013). Construction Economics: A New Approach, Routledge. Norman G (1990). Life Cycle Costing. Property Manage. 8(4):344-356. |

|

|

|

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development - OECD (2001). Measuring Productivity. France. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Available on http://www.oecd.org/ |

|

|

|

Republic of Zambia - RoZ (2011). National Programme on Sustainable Consumption and Production for Zambia. |

|

|

|

Royal Kingdom of Cambodia - RoZ (2009). National Sustainable Development Strategy for Cambodia. |

|

|

Spangenberg JH (2005). Economic Sustainability of the Economy: Concepts and Indicators. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. 8(1):47-64.

Crossref |

|

|

Stavins RN, Wagner AF, Wagner G (2003). Interpreting Sustainability in Economic Terms: Dynamic Efficiency plus Intergenerational Equity. Econ. Lett. 79(3):339-343.

Crossref |

|

|

|

Tagaza E, Wilson JL (2004). Green Buildings: Drivers and Barriers - Lessons from Five Melbourne Developments. Report Prepared for the Building Commission by the University of Melbourne and Business Outlook and Evaluation. |

|

|

Tse, RY, Ganesan S IV (1997). Causal Relationship between Construction Flows and GDP: Evidence from Hong Kong. Constr. Manage. Econ. 15(4):371-376.

Crossref |

|

|

|

U.S. Energy Information Administration (2011). Emissions of Greenhouse Gases in the United States 2009. Washington D.C. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Available on http://www.epa.gov/ |

|

|

|

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development - UNCTAD (2011). The Least Developed Countries Report 2011: The Potential Role of South-South Cooperation for Inclusive and Sustainable Development. |

|

|

|

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe - UNECE (2009). Measuring Sustainable Development. New York and Geneva. |

|

|

|

United Nations Environment Programme - UNEP (2011). Buildings: Investing in energy and resource efficiency. |

|

|

|

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change - Conference of Parties 17 - UNFCCC (2011). Working Together Saving Tomorrow Today. |

|

|

|

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change - UNFCCC (1998). The Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC. |

|

|

|

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2007). Climate Change: Impacts, Vulnerability and Adaptation in Developing Countries. Bonn. |

|

|

|

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2010). Conference on Promoting Green Building Rating in Africa. Nairobi, Kenya. |

|

|

|

United Nations Human Settlements Programme (2010). Nepal Urban Housing Sector Profile. |

|

|

|

Urban Catalyst Associates (2005). Building Green for the Future - Case Studies of Sustainable Development in Michigan. Ann Arbor, Michigan, University of Michigan. |

|

|

|

World Green Building Council (2013). The Business Case for Green Building - A Review of the Costs and Benefits for Developers, Investors and Occupants. World Green Building Council. Available on http://www.worldgbc.org/worldgbc/become-member/members/ |

|

|

Zhang XL, Shen LY, Wu YZ (2011). Green Strategy for Gaining Competitive Advantage in Housing Development: A China Study. J. Cleaner Prod. 19(1):157-167.

Crossref |

|

|

|

United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (2012). Economic Development in Africa: Structural Transformation and Sustainable Development in Africa. P. 15. |