ABSTRACT

Adopting the descriptive approach, this study examined the performance of 2013 capital budget in Nigeria in line with attainment of the transformation agenda in the country. The findings suggest that the level of capital budget implementation is insufficient to foster the desired development. This poor performance is attributable to inadequacy in the budget implementation plans, non-release or late release of budgeted funds and lack of budget performance monitoring. The study recommends a paradigm shift in budgeting by developing a realistic and credible budget guided by relevant fiscal rules in tandem with the needs and financial capability of the country in order to take care of uncertainties in revenue. This entails creating a realistic projection of reliable income, a healthy mix of diverse revenue streams and consistency with the nation’s goals. In this regard, both the executive and the legislature should collaborate in making sure that funds are released on time, and the financing of the budget could be through long-term commercial bonds, export credit finance, private equity, infrastructure bonds and foreign aids.

Key words: Budget, capital budget, planning, transformation agenda.

A major policy challenge confronting both developed and developing economies is the process of determining how to raise, allocate and spend public resources and the ways the resources are utilized goes a long way in determining how public policy objectives are achieved. In addressing these challenges of the country, the budget is often designed focusing on the preferred sectors of the economy. This is while in formulating the budget, government makes a number of choices regarding its financing and how available resources are allocated to existing or new programmes and institutions (Adrian, 2001; ODI, 2004).

With the budget, a clear statement of intent can be provided, often more accurate than the policies or plans on which they are based so as to attain the overall development of the country. As enunciated by Premchand (2000), a new dimension in public budgeting have been planning for economic development through economic growth, employment and more favourable income redistribution, and thus provide an operational framework for the attainment of macroeconomic as well as microeconomic goals of the country. This approach was adopted because it was observed that that planning models adopted in the 19070s did not generate the expected benefits due to its rigidity and inability to generate resources, thus contributing to a highly fragile state of public finances. To attain the desired economic development, attention was therefore focused on long-term budgeting strategy that would facilitate the integration and proper romance of multi-year programmes with annual budgets. Such approach has been so extensive that it is difficult to consider budgeting for economic development without a consideration of organized economic planning and associated formulation of medium-term and long-term plans (Premchand, 2000).

It has been observed that in most developing countries, annual budgets have little or no connection with development plans. As pointed out by Lacey (1989), in most developing countries including Nigeria, there is always a disjoint between broad objectives of the plan and inter-connection in budget preparation. More empirical evidence from Nigeria and Ghana suggests that national budgets possess the principal features of repetitive budgeting and whose source of financing is unpredictable. This unpredictability of resource flows creates uncertainty in resource allocation and capital budget implementation (Omelehinwa and Roe, 1989; Nwagu, 1992).

Other studies have also shown evidence that the manner in which new projects have been planned, appraised, approved and included in the budget are not in tandem with the laid down guidelines designed to facilitate the linkage between development plans and annual budget. The capital budget of a country is seen as a potent tool of in the provision of capital investment, and it is often more directly related to development because it contributes to the capital stock of economy needed to drive the growth process.

But in Nigeria, available evidence reveals that annual budgets over the years have not contributed significantly to the growth process of the economy due to weak implementation of capital budget (Obadan, 2000; Oke, 2013). This view was made more evident by Ogujiuba and Ehigiamusoe (2014) when they assert that only 51% of the total budgeted funds for capital expenditures in the 2012 Federal government budget were utilized. Of all the factors contributing to the increasing gap between budgeted and actual performance is the seeming obsession with projection in crude oil revenue.

As enunciated by Kwanashie (2013), the 2013 budget is one of the series geared towards achieving the targets of the country’s goal of becoming one of the 20 leading economies in the world by 2020. Towards achieving this dream, the government has introduced variety of programmes, and the main vehicle for achieving the targets of the transformation agenda is the various annual budgets embedded within a medium term expenditure framework.

Although since the mid-1980s, government have introduced economic reforms to make the economy market based and make the contribute more to accumulation of capital, government still plays a major role in enhancing the pace of capital accumulation in the economy.

In essence, the economic reform agenda intends to make Nigeria a high income country, knowledge-based market economy and provide quality of life to all Nigerians (NFG, 2000). In the face of poor capital budget implementation in Nigeria over the years, how has capital budget contributed to the attainment of the goals of the transformation agenda?

The objective of this paper therefore is to examine the 2013 capital budget implementation within the context of the attainment of economic reform agenda. The 2013 budget was selected because its implementation was based on uncertain global economic environment that seemingly threatens the rapid transformation of most transiting economies.

Overall context of the 2013 federal budget

The 2013 federal budget took its bearing from the nation’s medium and long-term goals which has been embedded in the various planning documents and reform programmes. Since the articulation of the programmes, each budget was expected to make real the various goals, and assist achieve the targets set in the documents.

The essence of focusing on capital budget is that it goes a long in accentuating economic performance. The 2013 federal budget was faced with myriad of problems. The challenge of the Euro zone debt, economic slowdown in China and India, slow recovery the United States economy, growing challenge to World peace from North Korea and political tension in the Arab world impacted negatively on global economic performance in 2013. This has resulted in further budget deficit where budget is implemented by borrowing both internally and externally.

Inspite of the rising debts, the overall budget size continues to increase. While the trend in developed economies has been to constrain public spending and focus on policies that would revive private sector to aid productive activities, Nigeria continues an expansionary fiscal posture even while claiming consolidation.

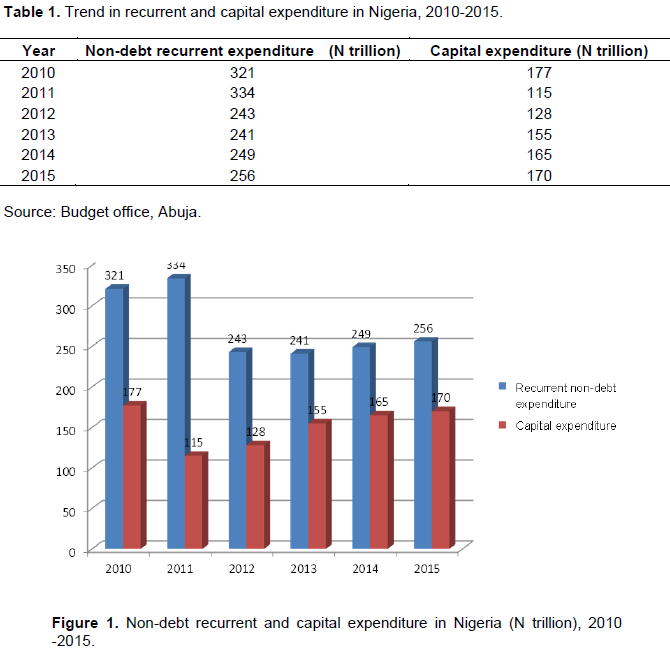

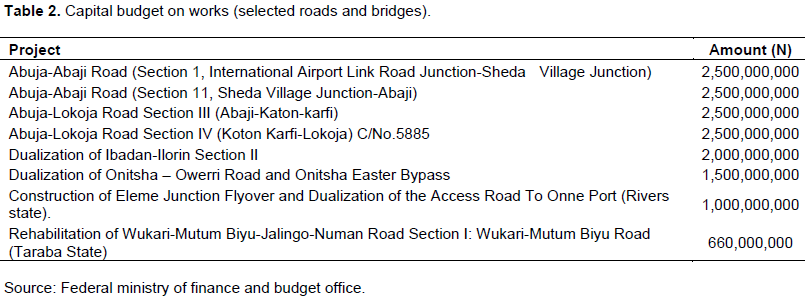

Aggregate expenditure for 2013 is N4, 987 trillion as against the N4, 649 trillion budgeted for 2012. This represents about 5% increase in the overall budget estimates. Of this amount, approved capital expenditure was N1, 621 billion representing about 31.3% while recurrent expenditure was N2.386 trillion, representing 68.7%. The trend in capital expenditure and non-debt recurrent expenditure in Nigeria from 2010 to 2015 is depicted in Table 1. Table 1 has revealed that there was a great divergence between capital expenditure and recurrent expenditure. This divergence can be further visualized in Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows the share of recurrent and capital expenditures from 2010 to 2015, with recurrent expenditure having larger portion. With this trend, the concern is that recurrent expenditure will have a decreasing relative effect on capital budgets that contributes to building capital for sustained growth. The prioritization of capital expenditure is therefore essential because growth is driven by capital budget which serves as the public sector share of the total capital accumulation. Public sector capital also addresses critical infrastructural challenges which are catalytic to the growth of the private sector, and thus private capital accumulation.

The descriptive approach is adopted by this study. This approach best fit the ascertainment and description of characteristics of variable in this research. In addition, a descriptive approach will enable the researcher to collect enough information necessary for generalization. For the purpose of statistical inferences, the stratified random sampling method is used to select relevant projects from various ministries, department and agencies (MDAs). Secondary data were obtained from Ministry of Finance, Budget office and National Bureau of Statistics (2014).

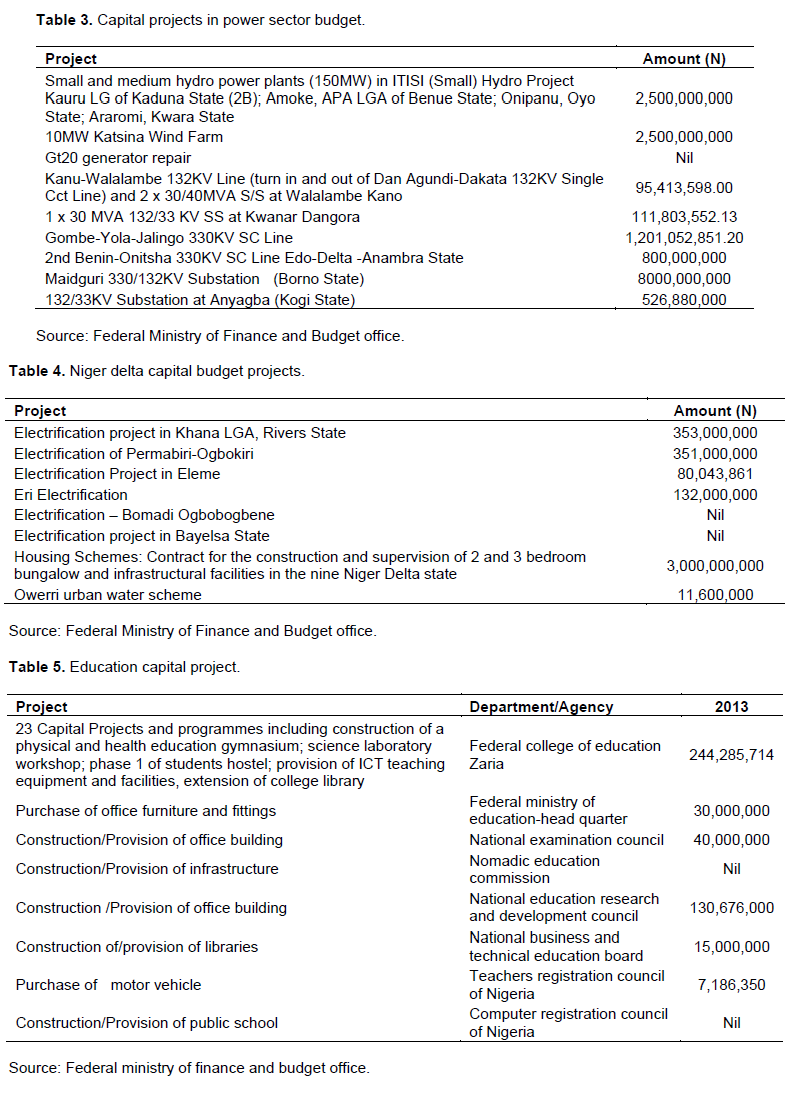

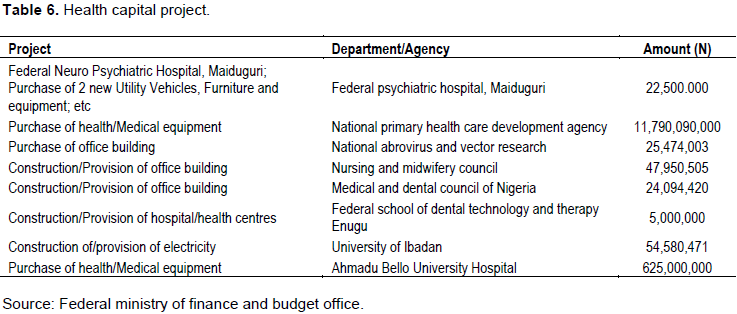

From the various sectors of the economy, a total of 1,746 projects were submitted by various ministries, department and agencies (MDAs) for implementation excluding those under governance, general administration, defense and security.

Out of this, 685 projects were admitted as key projects based on some criteria such as currently existing capital projects under the NIP of the Vision 20:2020, potential for significant economic impact, already on-going or under development, essential to the attainment of sector goals, achieve significant progress in 4 years, capable of attracting private sector investment, donor funds or soft loans, impact on employment and welfare, clear justification for budget commitment, alignment with stated policies, clear implementation arrangements, Millennium Development Goal (MDG) funded projects, projects with feasibility reports, inter-linkages with other sectors and having measurable targets, indicators and outcomes (NILS, 2012).Below is capital budget of selected sectors of the economy for the year, 2013. For the sectors under review, projects considered are road and bridges, water resources, Niger Delta, education and health. These projects have high socio-economic impact on the overall growth of the economy (Tables 2 to 6). A detailed analysis of the aforementioned project reveals that they are in tandem with the ideology in the transformation agenda. In line with the transformation agenda, specific budgetary projections were made for the various sectors. In our discussion, proposed and projections in the 2013 budget will be compared to determine the consistency of the development agenda with actual budget projections.

For roads and bridges, the transformation agenda made provision for N170billion as 2013 budgetary investment for capital projects, but for the same year, works had a capital budget of N151, 250,000,000, revealing a shortfall of N18, 750,000,000. This implies is that there was inconsistency between the development agenda and the budget.

In line with the transformation agenda, N85billion was to be allocated for capital projects within the power sector but N70billion was actually budgeted, suggesting again a funding gap of N15billion. Education was projected to have capital investment of N100billion but actual amount allocated was N60.14billion.

Thus, there was a shortfall of about N39.86billion between development plan and actual budget. It was only in the health sector that it experienced an overflow of N1.7billion for capital projects against development agenda’s projection. While the transformation agenda projected N54billion capital investment, the sector got the sum of N55.7billion. The projected capital project in 2013 for Niger Delta is N77.6billion but actually allocation was N39.8billion, that is, 51.2% of the budgeted amount, showing a funding gap of 48.8%. The budgeting process in Nigeria which has been basically incremental in nature has often not been able to address the challenges of the country. Meanwhile, the transformation agenda was put in place to improve the wellbeing of the citizens through the implementation of the budget. Judging from the 2013 capital budget implementation, although some progress has been made in some sectors, others remain in dire need. The constraints in these sectors include poor capital budgetary allocation and infrastructural deficits.

A basic challenge the 2013 capital budget was the uncertainty surrounding its funding and implementation. The capital budget was financed mainly from allocations which comprise of the share from the Federation Account, VAT and internally generated revenue. These sources are volatile in nature and heavily dependent on oil revenue. Timely release of capital funds is necessary for the effective implementation of capital budget. But experience of the last decade has shown that late release and often non release of capital funds partly explains the existence of abandoned projects. This challenge repeated itself in 2013 (NILS, 2012).

The 2013 capital budget has also underperformed in other two critical aspects. First, the efficiency of expenditure has been low because expenditure outcomes have not met with expectations. The second aspect relates to the late and often times non release of funds leading to under performance. For example, less than 70% of the capital projects were undertaken.

The under-performance of the capital budget was to the sum of N375.65 billion and actual capital expenditure amounted to N771.1 billion compared to the budget estimates. On the whole it is generally accepted weak project conceptualization, non-release of funds, costing, and planning and project management of project cycle are major limited factors to full capital budget implementation. This is a major obstacle in implementation of the reform agenda.

There is also another challenge on how to make the private sector contribute better to attainment of the transformation agenda. The programme will not succeed if the private sector is not fully engaged.

This study assesses the consistency level in 2013 capital budget proposals of selected key sectors of the economy in line with the transformation agenda, and found that there was high level of inconsistency. It also found that funding gaps existed for 87.5% of the projects both in terms of budgetary allocations and actual amount released.

The challenges that were noticed included disconnect between available resources and number of projects, inadequate budgetary allocation and delayed releases of funds. In ridging the gap between planning and budgeting, the government should ensure that selected projects are justifiable as priorities under the development agenda. In this regard, budget initiation and implementation must therefore be guided by relevant documentation in the transformation agenda and the medium term expenditure framework.

There is therefore the need for better fiscal rules to guide the preparation of the budgets. The legislature should also consider increase appropriation to the sectors reviewed because of their importance in meeting the transformation agenda. Such increase can be funded from savings in overhead expenditure. It is important to match capital projects with the available resources. This will reduce waste and abandoned projects and facilitate quick delivery of capital budgets.

Most importantly, the legislature in collaboration with the executive should consider alternative capital budget funding mechanisms such as public-private partnership (PPP), long term commercial bonds and export credit finance.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Adrian F (2001). The Basic Budgeting Problem: Approaches to Resource Allocation in the Public Sector and their Implications for Pro-Poor Budgeting ODI Working Paper 147.

|

|

|

|

Kwanashie M (2013). 2013 Capital Budget and National Development", Paper Presented at the ICAN Annual Budget Seminar. Lagos.

|

|

|

|

|

National Bureau of Statistics (2014). Annual Abstract of Statistics, Abuja Nigerian Federal Government (2000), Financial Regulations Federal Government Press Lagos.

|

|

|

|

|

Nigerian Federal Government (NFG) (2000), Financial Regulations Federal Government Press Lagos.

|

|

|

|

|

NILS (2012). 2013 Budget Bill Review, National Institute for Legislative Studies Abuja.

|

|

|

|

|

Nwagu EOC (1992). Budgeting for Development: The Case of Nigeria. Public Budgeting Fin. 12(1):73-82.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Obadan MI (2000). National Development Planning and Budgeting in Nigeria: Some Pertinent Issues. Broadway Press Limited.

|

|

|

|

|

Ogujiuba KK, Ehigiamusoe K (2014). Capital Budget Implementation in Nigeria: Evidence from the 2012 Capital Budget. Contemp. Econ. 8(3):299-314.

|

|

|

|

|

Oke MO (2013). Budget Implementation and Economic Growth in Nigeria. Dev. Country Stud. 3(13).

|

|

|

|

|

ODI (Overseas Development Institute) (2004). New Thinking on Budgets and Aid, ODI Briefing Paper, May.

|

|

|

|

|

Omelehinwa E, Roe EM (1989). Boom and Bust Budgeting: Repetitive Budgetary Processes in Nigeria, Kenya and Ghana. Budgeting Fin. 9(2):43-65.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Premchand A (2000). Budgeting for Economic Development: Evolution and Practice of an Ide"'. In: Premchand, A. Control of Public Money: The Fiscal Machinery in Developing Countries, Oxford University Press, New Delhi.

|

|