ABSTRACT

Increased competition and globalization have made it imperative for banks to achieve high efficiency in order to generate required returns. This paper investigates the relationship between bank efficiency estimates, derived from both Stochastic Frontier Approach (SFA) and Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) and share prices of banks listed on the Ghana stock exchange. The results give an indication that changes in cost and profit efficiency are reflected in stock performance and that efficiency is directly observed by the public and reflected in share prices, though SFA efficiency scores are not reflected in share prices as being equally important as compared to DEA efficiency scores.

Key words: Efficiency, share price changes, Stochastic Frontier Approach (SFA), data envelopment analysis (DEA).

Increased competition and globalization have made it imperative for banks to achieve high efficiency in order to generate required returns. Firms’ efficiency mainly depends on the manner they produce output from inputs (Berlamino and Fernando, 1997). Cost or profit efficient banks have the tendency to generate greater returns on equity and will therefore result in better stock performance. In terms of efficiency estimations, a decline in the cost or an increase in the profitability of a bank is expected to create better financial performance resulting in greater stock returns. In an efficient market therefore, a change in cost or profit efficiency should be incorporated in the price formation process. The Ghanaian banking sector has undergone several restructuring and transformations, as part of the country’s restructuring and transformation program to enable the sector offer first class services within the globalized financial system. These reforms have moved the financial sector from a regime characterized by controls to market based regime. Commercial banks account for 75% percent of the total assets of the financial system and of the twenty seven commercial banks operating in Ghana as at December 2013, thirteen are subsidiaries of foreign banks, having a market share of approximately 51% of bank assets (BOG, 2014). All the commercial banks are private limited companies. The industry experienced five year historic (2009-2013) average growth rate of approximately 27 and 28% in total assets and deposits, respectively.

Both parametric and non-parametric approaches, as opposed to the traditional accounting ratio measures, have recently been used for the empirical estimation of bank efficiency (Sarpong et al., 2012). Parametric frontier techniques are considered more sophisticated as compared to the non-Parametric frontier since the approach is able to incorporate both input allocative and technical efficiencies (Berger and Mester, 1997). Iqbal and Molyneux (2005) found that frontier approaches are considered superior to standard financial ratio analysis because they use programming or statistical techniques that remove the effect of differences in input and output prices and other exogenous market factors affecting the standard performance of firms.

Bank efficiency which can be proxied by revenue, profit, or cost can be classified into technical and allocative efficiencies. These theories which are based on economic foundations for analyzing bank efficiency focus on economic optimization in reaction to market prices, competition and other market conditions rather than being solely based on the use of technology.

Farrell (1957) greatly influenced by Koopmans (1951)’s formal definition and Debreu (1951)’s measure of technical efficiency introduced a method to decompose the overall efficiency of a production unit into its technical and allocative components. Farrell characterized the different ways in which a productive unit can be inefficient either by obtaining less than the maximum output available from a determined group of inputs (technically inefficient) or by not purchasing the best package of inputs given their prices and marginal productivities (allocatively inefficient). According to Rangan and Grabowski (1988), most technical inefficiencies are due to pure technical inefficiency (wasting inputs) rather than scale inefficiency (operating at non-constant returns to scale).

Bank efficiency studies have been criticized for ignoring the revenue and profit side of the banks’ operations. In fact, banks that show cost inefficiencies might be able to generate greater profits than some cost efficient banks (Berger and Humphrey, 1992; Berger and Mester, 1997).

Revenue efficiency measures the change in a bank’s revenue adjusted for random error, relative to the estimated revenue obtained from producing an output bundle as efficiently as the best-practice bank in a sample facing the same exogenous variables. Empirical studies have found that revenue inefficiency can be attributed primarily to technical inefficiency as opposed to allocative inefficiency (Berger et al., 1995). The main weakness of the revenue concept is that it does not take into account the increased costs of producing higher quality services and thus focuses on only one side of the overall financial picture of a bank (DeYoung and Nolle, 1996).

Cost efficiency measures the change in a bank’s variable cost adjusted for random error, relative to the estimated cost needed to produce an output bundle as efficiently as the best-practice bank in a sample facing the same exogenous variables, which include variable input prices, variable output quantities and fixed net puts (inputs and outputs) (Kwan and Eisenbeis, 1997; Berger and DeYoung, 1997). Cost inefficiency arises due to technical inefficiency, which results in the use of an excess or sub-optimal mix of inputs given input prices and output quantities (Williams, 2004).

Profit efficiency shows how well a bank is predicted to perform in terms of profit relative to other banks in the same period for producing the same set of outputs. Most empirical studies on profit efficiency report efficiency levels that are lower than cost efficiency levels (Maudos et al., 2002).

Bank efficiency has been measured severally using different frontier techniques to measure either cost or profit efficiency separately, or a particular frontier approach for both cost and profit efficiency but very little literature exist for different approaches measuring both cost and profit efficiency in the same studies. The main objective of this study was to investigate the relationship existing between bank efficiency (cost and profit) estimates, derived from both Stochastic Frontier Approach (SFA) and Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) and stock performance of a sample of five banks listed on the Ghana Stock Exchange over the period of 2009-2013, showing how changes in efficiency scores help to explain changes in stock prices. It is expected that efficient firms are more profitable, directly through lower costs or higher output, or indirectly through higher customer satisfaction and therefore generate greater shareholder returns (Kane and Kaufman, 1993; Kwan and Eisenbeis, 1996). Improvements in cost or profit efficiency are expected to create better financial performance resulting in better stock performance. The results seem to support this hypothesis. In addition, SFA efficiency scores are not reflected in share prices as being equally important as compared to DEA efficiency scores.

Literature review

A large proportion of literature on banking efficiency has concentrated on the United States (Evandoff, 1991; Hughes and Mester, 1993; Mester, 1996; Miller and Noulas, 1996; Berger et al., 1999) and European banking industries (Pastor et al., 1997; Mendes and Rebelo, 1999; Dietsch and Weill, 1999; Lozano-Vivas, 1997; Fries and Taci, 2005), though some literature also exist for some emerging economies, (Hao et al., 2001; Sufian, 2009; Thagunna and Poudel, 2013). Some studies also explored various issues of bank efficiency such as the estimates from different approaches (Berger and Humphrey, 1992; Berger and Mester, 1997; Bauer et al., 1998), the impact of risk (Mester, 1996; Kwan and Eisenbeis, 1997; Altunbas et al., 2000; Pasiouras, 2007), off-balance sheet activities (Tortosa-Ausina, 2003; Pasiouras, 2007) and the role of markets, regulation and other environmental factors (Dietsch and Lozano-Vivas, 2000; Altunbas et al., 2000; Berger and DeYoung, 2001; Chaffai et al., 2001; Cavallo and Rossi, 2002).

Parametric and non-parametric approaches have been utilized for the empirical estimation of bank efficiency. Parametric approaches used econometric techniques and impose a priori on the functional form for the frontier and the distribution of efficiency. A non-parametric approach, on the contrary, relies on linear programming to obtain a benchmark of optimal cost and production-factor combinations. Both stochastic and deterministic methods are used in the measurement of bank efficiency. Stochastic allows random noise due to measurement errors, whiles deterministic on the contrary, attributes the distance between an inefficient observed bank and the efficient frontier entirely to inefficiency.

Significant proportion of recent bank efficiency studies concentrated on cost and profit efficiency, (Kwan and Wilcox, 1999; Kohers et al., 2000; Berger et al., 2000) and use X-efficiency measures to explain bank profitability. In measuring the cost efficiency of banks, comparison of observed cost and output-factor combinations is made, with optimal combinations determined by the efficient frontier (Fiorentino et al., 2006). Profit efficiency is measured by relating profits to input prices and output prices. However, Berger and Mester (1997) used the concept of alternative profit efficiency to relate profit to input prices and output quantities. Alternative profit efficiency compares the ability of banks to generate profits for the same level of outputs and thus reduces the scale bias that might be present when output levels are allowed to vary freely.

Studies on the behaviour of stock markets have generally shown that earnings information is reflected in stock prices, even though the magnitude of changes in stock prices is different from that of change in earnings. Cost or profit efficient banks have the tendency to generate greater returns on equity and will therefore result in greater better stock performance. In terms of efficiency estimations, a decline in the cost or an increase in the profitability of a bank is expected to create better financial performance resulting in greater stock returns. In an efficient market therefore, a change in cost or profit efficiency should be incorporated in the price formation process. Eisenbeis et al. (1999) estimated the cost efficiency of a sample of large US bank holding companies, using both DEA and SFA approaches, examined the relationship between the efficiency and their risk-taking and stock price behaviour. Their results indicate that while both parametric and non-parametric efficiency estimates produce informative efficiency scores, the stochastic frontier efficiency estimates are more accurate in explaining stock price behaviour. Liadaki and Gaganis (2010) examined the relationship between cost and profit efficiency of 15 EU listed banks and their stock returns. Their results indicate a significant positive relationship between change in profit efficiency and bank stock returns but no relationship between change in cost efficiency and stock returns.

The study utilized balanced panel data from five listed banks (Ghana Commercial Bank, HFC Bank, Ecobank Ghana, SG-SSB (now SG) Bank and CAL Bank) out of the nine banks listed on the Ghana Stock Exchange, over the period of 2009-2013. The published annual reports and financial statements of these listed banks were obtained from their respective official sites. Weekly stock prices of these listed banks were obtained from the Ghana Stock Exchange.

In assessing the relationship between changes in efficiency (cost and profit) and stock returns for banks listed on the Ghana stock exchange, the authors calculated stock performance as the annual stock returns, calculated for each bank by adding weekly returns. Then employed SFA and DEA approaches for estimating the cost and profit efficiency frontiers for the banks. Finally, they regressed the stock performance on the corresponding yearly change in the frontier efficiency measures. If a link can be identified statistically, this could be used to explain stock price fluctuations. The study conceptualized that a bank’s stock returns is a function of changes in cost and profit efficiency as represented by Equation 1:

Where: Rit is the stock returns of the ith bank; CEit is the changes in cost efficiency of the ith bank; PEit is the changes in profit efficiency of the ith bank.

This study employs the standard DEA approach which assumes variable returns to scale, input oriented and output oriented cost minimization models. Since the main objective of this research is to estimate the overall performance of a specific bank relative to ‘best practice’ rather than its sources of inefficiency, only overall efficiency estimates, rather than their detailed decomposition, are presented.

The difficulty in DEA analysis is the identification of benchmarks which have no extreme behaviour or influenced by other factors. This is because the very efficient units utilized as benchmarks might be outliers which can impact on the estimated efficiencies for the other units. For this reason, the authors have chosen as a cut-off point, a super-efficiency value equal to 130% to identify first pass super-efficient units. There was therefore no unit in the sample grossly dissimilar from the bulk of observations which could introduce bias in the estimation of efficient boundary.

The SFA approach was utilized for the efficiency estimation in addition to the DEA. The Battese and Coelli (1995) model of a stochastic frontier function for panel data, which allows the estimation of efficiency in a one-step procedure is employed since it eliminates some of the anomalies from the two-step procedure. The stochastic frontier production model is specified as follows:

Where TCt,i is a measure of total cost of the ith firm in the tth period, Pt,i and Qi,t are the vectors of input prices and output quantities; β represents a vector of unknown parameters; Vi,t are random errors which are assumed to follow a symmetrical normal distribution and are independently distributed of Ui,t ; and Ui,t are independently distributed inefficiency effects. The profit efficiency function is specified as follows:

Where TPt,i is a measure of total profit, which is specified as the net profit before tax, of the ith firm in the tth period and all other variables are as defined in the total cost function. In measuring the efficiency under the profit function, the composite error term is considered as Ei = Vi-Ui.

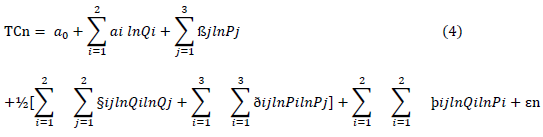

The standard translog functional form is employed for this study because though the translog and the Fourier flexible functional form, which is a global approximation that includes a standard translog plus Fourier trigonometric terms, yield essentially the same average level and dispersion of measured efficiency, Altunbas and Chakravarty (2001) identified limitations with the Fourier suggesting that the translog is the preferred model approach. The standard translog functional form for multi products is specified as follows:

TC is a measure of the total costs of production comprising total operating expense and interest expense; Qi (i = 1,2) are output quantities where Q1 is total loans; Q2 is other earning assets; Pj ( j = 1,2,3) are input prices where P1 is the price of labour (calculated as total personnel expense divided by total assets); P2 the price of deposits (calculated as interest expense divided by corresponding liabilities (deposits, and other short term funding); P3 the price of equity (calculated as total capital expense divided by total fixed assets); is a two component stochastic error term; and are parameters to be estimated.

Profit functions are estimated similarly as cost functions in Equation 4 except that the dependent variable is replaced with total profit (profit before tax) on the left-hand side of the equation. The bank stock performance represents the yearly percentage gain or loss of the value of the stock which is calculated by adding the weekly returns. The stock return is calculated as follows:

Where Ri,t is the stock return of the ith bank at the close of period t; Pi,t is the stock price of the ith bank at the close of period t; Pi,t is the stock price of the ith bank at the close of the period immediately prior to period t.

Panel data analysis is utilized in order to analyze the relationship between the efficiency of banks and their stock price performance. The panel data regression model takes the following form:

Where dependent variable Yi,t is the annual stock return of ith bank in the tth period; represents the slope parameters; the parameter is the overall constant in the model; Xi,t is the annual percentage change in X-efficiency (DEA and SFA), risk (annual change in total equity to total assets ratio) and size (annual change in total assets) , of the ith bank in the tth period; and Ui,t are the error terms for i=1,2, ….N cross-sectional units observed for periods t=1,2,….T; and Table 1 presents the main descriptive statistics of the input and output variables.

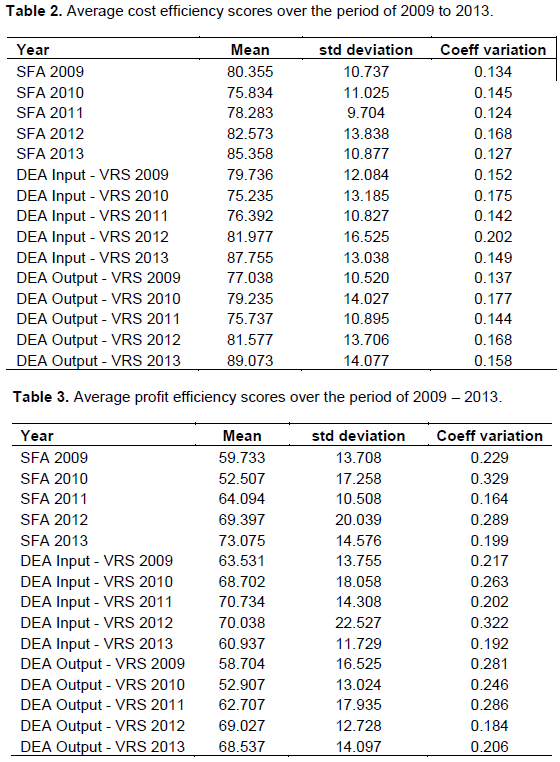

The cost efficiency estimates based on parametric and non-parametric frontier techniques are shown in Table 2. The measure of efficiency takes a maximum value of 100, which corresponds to the most efficient bank in the sample. The cost efficiency estimates range between 75 and 89%, with an average of 80%, thereby indicating average inefficiency of nearly 20%. The profit efficie estimates are also presented in Table 3. The profit efficiency estimates range between 53 and 73%, with an average of 64%, thereby indicating average inefficiency of 36%.

The DEA cost and profit efficiency estimates present greater variability than SFA cost and profit efficiency estimates. It can be noted that cost efficiency scores are higher than profit efficiency scores. This might be an indication that banks are much interested in increasing their investment activities (Mamatzakis et al., 2008). Even though, the overall trend for cost and profit efficiency estimates is not constant, there is improvement over the years.

The cost and profit efficiency scores were estimated using stochastic frontier and data envelopment methods. Thereafter, the cumulative yearly stock returns (CYSR) were regressed against the efficiency estimates, whiles controlling for risk and size, which have been known to influence bank stock performance, using changes in equity to total assets ratio and changes in total assets respectively, in order to investigate the relationship that exist between efficiency and share price changes. In order to determine the choice of appropriate panel data model, the Breusch-Pagan Lagrange Multiplier and Hausman specification tests were employed and the results of these tests indicate that the fixed effect model is preferable. Yearly dummy variables were introduced into the model to take into consideration the potential time effects in the stock returns. To control for cross-section heteroscedasticity, the model was estimated using White’s transformation, with corrected degrees of freedom.

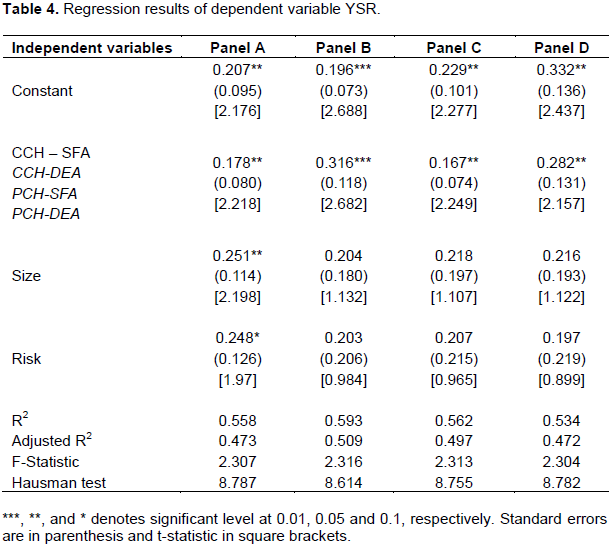

The regression results for SFA cost, DEA cost, SFA profit and DEA profit efficiency estimates are presented in panel A,B,C and D of Table 4, respectively. If changes in cost and profit efficiency are incorporated in stock prices, then a positive association is expected between these efficiency changes and changes in stock prices.

The results show that both SFA and DEA changes in cost efficiency (CCH) estimates have a positive and statistically significant impact on changes in stock prices, though expected increase in share prices is about double for a point increase in DEA cost efficiency to that of SFA cost efficiency, as indicated by the slope coefficient of SFA (0.178) and DEA (0.316), respectively. These findings are indicative that the shares of cost efficient banks tend to perform better than that of inefficient counterparts. This shows that if a bank is cost efficient, this will be directly reflected in the future expectations of the banks’ share prices. These results are consistent with the findings of Becalli et al. (2006). The explanatory variables to account for the impact of efficiency change on share price were both statistically significant but size was statistically significant at 0.05, risk was 0.1 for SFA efficiency estimates. They were however not statistically significant for DEA efficiency scores. The explanatory power of SFA cost changes in the variability of stock returns is 47.3%, whiles that of DEA cost changes was 50.9%.

The regression results for SFA and DEA changes in profit efficiency (PCH) estimates are significantly positive to changes in share prices. Similar to the results of cost efficiency estimates, the slope coefficient of 0.167 for SFA and 0.282 for DEA indicate that the expected increase in stock prices resulting from point increase in DEA is greater than as caused by a point increase in SFA. These results show that profit efficiency is directly observed by the public and reflected in share prices. This shows that the stocks of profit efficient banks tend to outperform that of inefficient banks. These results are consistent with the findings of Ioannidis et al. (2008)

The explanatory variables (size and risk) to account for the impact of profit efficiency change on the stock returns were not statistically significant for SFA and DEA estimates. This shows that size and risk do not contribute to the explanation of changes in share prices. The explanatory power of SFA and DEA profit efficiency changes in the variability of share prices are 49.7 and 47.2%, respectively.

Banks have to achieve high efficiency as a result of increased competition and globalization in order to generate required returns. This study investigates the relationship that exists between the cost and profit efficiency estimates of banks and their corresponding stock performance in order to determine whether the efficiency estimates contribute in the explanation of fluctuations in share prices of banks in Ghana. The study utilized parametric and non-parametric frontier techniques, specifically SFA and DEA, for estimating bank efficiency. The stock performance was regressed on the corresponding yearly change in the frontier efficiency estimates to determine whether efficiency scores have explanatory power on share price fluctuations.

The results give an indication that changes in cost and profit efficiency are reflected in share prices, though SFA efficiency scores are not reflected in share prices as being equally important as compared to DEA efficiency scores. This suggests that shares of cost and profit efficient banks tend to perform better than their inefficient counterparts. With the exception of results from SFA cost efficiency estimates, the explanatory variables (size and risk) to account for the impact of efficiency changes on share price changes were not able to increase the model’s explanatory power significantly.

REFERENCES

|

Altunbas Y, Chakravarty S (2001). Frontier cost functions and bank efficiency. Econ. Lett. 72:233-240.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Altunbas Y, Liu MH, Molyneux P, Seth R (2000). Efficiency and risk in Japanese banking. J. Bank. Financ. 24:1605-1628.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Battese GE, Coelli TJ (1995). A model for technical inefficiency effects in a stochastic Frontier production function for panel data. Empirical Econ. 20:325-332.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Bauer PW, Berger AN, Ferrier GD, Humphrey DB (1998). Consistency Conditions for Regulatory Analysis of Financial Institutions: A Comparison of Frontier Efficiency Methods. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 98:177-216

|

|

|

|

Becalli E, Casu B, Girardone C (2006). Efficiency and stock performance in European banking. J. Bus. Financ. Account. 33:245-362.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Berlamino A, Fernando G (1997). Linking and Weighting Efficiency Estimates with Stock Performance in Banking Firms. Financial Institutions Center; The Whaton School: University of Pennsylvania.

|

|

|

|

Berger A, DeYoung R (2001). The Effects of Geographic Expansion on Bank Efficiency. J. Financ. Serv. Res. 19(2): 163-184.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Berger A, Humphrey D (1992). Measurement and Efficiency Issues in Commercial Banking. In Z. Griliches (Ed.), Output Measurement in the Service Sectors, Chicago, University of Chicago Press. pp.245-279.

|

|

|

|

Berger AN, Demsetz RS, Strahan PE (1999). The consolidation of the financial services industry: Causes, consequences, and implications for the future. J. Bank. Financ. 23(2-4):135-194.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Berger AN, Humphrey DB (1992). Efficiency of financial institutions: international survey and directions for future research. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 98:175-212.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Berger AN, Mester LJ (1997). Inside the black box: What explains differences with efficiency of financial institutions? J. Bank. Financ. 21:895-947.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Berger AN, De Young R, Genay H, Udell GF (2000). Globalization of financial institutions: evidence from cross-border banking performance. Finance and Economics Discussion Series.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Chaffai ME, Dietsch M, Lozano-Vivas A (2001), Technological and environmental differences in the European banking industries. J. Financ. Serv. Res. 19(2/3):147-162.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Debreu G (1951). The Coefficient of Resource Utilization. Econometrica, 19(3):273-295.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

DeYoung R, Nolle DE (1996). Foreign-owned banks in the United States: Earning market share or buying it. J. Money Credit Bank. 28(4):622-636.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dietsch M, Lozano-Vivas A (2000). How the environment determines banking efficiency: a comparison between French and Spanish industries. J. Bank. Financ. 24(6):985-1004.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Eisenbeis RA, Ferrier GD, Kwan SH (1999). The Informativeness of Stochastic Frontier and Programming Frontier Efficiency Scores: Cost Efficiency and Other Measures of Bank Holding Company Performance. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta Working Paper, 99-23.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Farrell MJ (1957). The Measurement of Productive Efficiency. J. R. Stat. Soc. pp. 253-290.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Fiorentino E, Karmann A, Koetter M (2006). The cost efficiency of German banks: A comparison of SFA and DEA. Discussion Paper Series 2: Banking and Financial Studies No 10/2006.

|

|

|

|

Fries S, Taci A (2005). Cost Efficiency of Banks in Transition: Evidence from 289 Banks in 15 Post- Communist Countries. J. Bank. Financ. 29:55-81.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hao J, Hunter W, Yang W (2001). Deregulation and efficiency: The case of private Korean banks. J. Econ. Bus. 53:237-254.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hughes JP, Mester LJ (1998). Bank capitalization and cost: Evidence of scale economies in risk management and signalling. Rev. Econ. Stat. 80:314-325.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ioannidis C, Molyneux P, Pasiouras F (2008). The relationship between bank efficiency and stock returns: evidence from Asia and Latin America. University of Bath School of Management, Working Paper Series, 2008(10).

View

|

|

|

|

Kane E, Kaufman G (1993). Incentive Conflict in Deposit Institutions Regulation. J. Financ. Serv. Res. 19:167-187.

|

|

|

|

Kohers T, Huang M.H., Kohers N. (2000). Market Perception of Efficiency in Bank Holding Company Mergers: the Roles of the DEA and SFA Models in Capturing Merger Potential, Rev. Fin. Econ. 9(2): 101-120.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kwan S, Eisenbeis R (1997). Bank risk, capitalization and operating efficiency. J. Financ. Serv. Res. 12:117-131.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Liadaki A, Gaganis C (2010). Efficiency and stock performance of EU banks: Is there a relationship. Omega, 38(5):254-259.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Lozano-Vivas A (1997). Profit efficiency for Spanish savings banks. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 98(2), 381-394.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Mamatzakis E, Staikouras C, Koutsomanoli-Filippaki A (2008), Bank efficiency in the new European Union member states: Is there convergence? Int. Rev. Financ. Analysis, 17:1156-1172.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Maudos J, Pastor JM, Perez F, Quesada J (2002). Cost and profit efficiency in European banks. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Institutions Money, 12(1):33-58.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Mester LJ (1996). A study of bank efficiency taking into account risk preferences. J. Bank. Financ. 20:1025-1045.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Miller S, Noulas A (1996). The technical efficiency of large bank production. J. Banking Financ. 20:495-509.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Pasiouras F (2007). Estimating the technical and scale efficiency of Greek commercial banks: Paper 2006.17,School of Management, University of Bath, UK,

|

|

|

|

Sarpong DJ, Winful EC, Owusu-mensah M (2014). Assessing the performance of banks listed on Ghana stock exchange: financial ratio analysis, journal of economics and international finance, 6(7):144-164.

|

|

|

|

Sufian F (2009). Determinants of bank efficiency during unstable macroeconomic environment: Empirical evidence from Malaysia. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 23:54-77.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Thagunna KS, Poudel S (2013). Measuring Bank Performance of Nepali Banks: A Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) Perspective. Int. J. Econ. Financial Issues, 3(1):54-65.

|

|

|

|

Tortosa-Ausina E (2003). Nontraditional activities and bank efficiency revisited: a distributional analysis for Spanish financial institutions. J. Econ. Bus. 55(4):371-395.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Williams J (2004), Determining management behaviour in European banking. J. Banking Finance 28(10):2427-2460.

Crossref

|