Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

This study investigated the response of the different monetary policy channels to several macroeconomic variables in Nigeria and established the dominant channel on output from the period of 1986 to 2017 using quarterly data. Variables such as private sector credit, inflation rate, monetary policy rate, exchange rate, all share index and real output were used to carry out this investigation. The study adopted the structural break and structural VAR methods in achieving the objectives and found a significant standard deviation real effect on each monetary policy channel in the short term, while it also found that innovations arising from a channel itself caused the greatest shock on its future values. The findings further demonstrated that each monetary policy channel had a weak influence on output, with interest rate channel being the dominant channel of monetary policy on output. Finally, the paper suggested that the monetary authority should keep using interest rate as the major policy anchor through which monetary impulses are transmitted into the economy.

Key words: Monetary transmission mechanism, interest rate channel, exchange rate channel, credit channel, expectations channel, asset price channel, output, structural vector autoregressive (SVAR).

INTRODUCTION

Monetary policy is an intentional act by the apex bank to influence the magnitude, cost and accessibility of money in order to attain both internal and external balance within an economy (CBN, 2011). In many developing countries, including Nigeria, the major purpose of monetary policy is to ensure stable prices and sustainable growth. In order to achieve these objectives, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has employed different frameworks over the years. The first was the exchange rate targeting framework which was in effect from 1959 to 1973. This framework however gave way to the monetary targeting framework in 1974 due to the failure in the adoption of Bretton Woods fixed exchange rate system in 1972 and the switch in policy stance to control inflation and improve Nigeria’s balance of payment (CBN, 2011). Since 1974, monetary targeting strategies have been implemented in Nigeria.

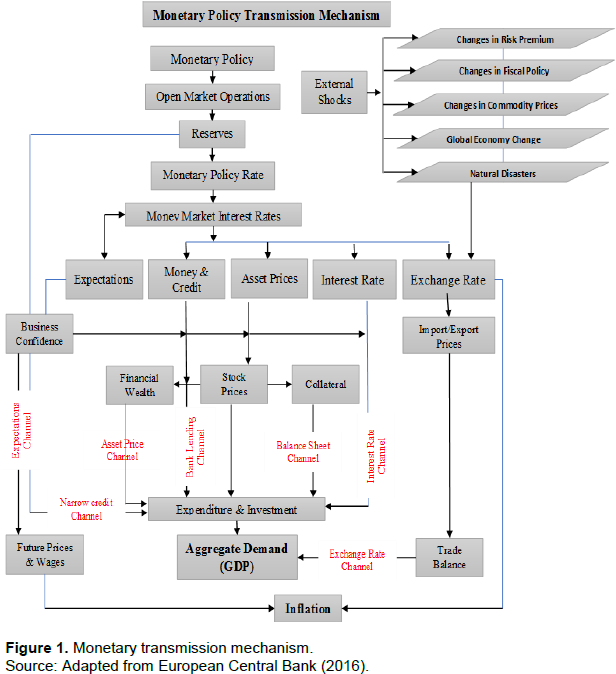

The channel through which monetary policy affects real economic activity is often referred to as the Monetary Transmission Mechanism (MTM). The mechanism predicts how monetary policy changes (for instance, a change in money supply or interest rates) transmit to economic activity and inflation in an economy (Lättemäe, 2003). There are several channels through which this can occur. These include: the credit channel, the traditional interest rate channel (money channel), asset price channel, exchange rate channel and expectation’s channel (Mishkin, 1995, 2004; Kuttner and Mosser, 2002; Williams and Robinson, 2016). These channels are not mutually exclusive as the effect of one channel could amplify or moderate its effect on another. These channels are also not time invariant; they evolve alongside changes in the overall economic and financial conditions of an economy (Tuaño-Amador et al., 2009).

In Nigeria, these channels have been used for the transmission of monetary policy into the economy. Furthermore, monetary policy instruments have been used as the policy anchor through which its policies affect the financial system and the economy at large. In between the anchor and the outcomes (output and prices) are the different instruments and channels through which the anchor achieves the intended outcomes as displayed in Figure 1. The different monetary policy channels are stationed to show how they affect output and inflation in an economy. Figure 1 shows that the decisions taken by the monetary authorities in their quarterly Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) will affect the transmission of monetary policy to the real economy (proxied by output and prices). In essence, this transmission process gives a description on how the different channels of monetary policy affect real economic activity within an economy. Indeed, these channels serve as the conduit through which monetary policies are implemented in an economy. It would further provide an insight on which channel will be more dominant on output in the course of the paper. The issue regarding the investigation of monetary transmission mechanism is as a result of its potential association with output and inflation in an economy. Economists do not however agree on the exact functioning of these channels in the literature (Olteanu, 2015). Some studies believe the influence of monetary policy may transmit into the financial sector in different ways (Lattemae, 2003; Mies and Tapia, 2003; Apergis et al., 2012), while some others believe the transmission channels may also overlap and this makes it difficult to differentiate them empirically (Tuano-Amado et al., 2009; Williams and Robinson, 2016; Lattemae, 2003). However, the crux of the debate regarding money transmission is related to its potential association with short-term real effects, since without such association, the contrast between real and nominal variables would lessen the macroeconomic stability objective desired by monetary authorities to a strategic framework that would only ensure price stability. An additional challenge may stem from the fact that some important factors that affect monetary transmission mechanism within an economy are not considered or measurable. For example, Lättemäe (2003) was of the opinion that there was no direct measure for the expectations channel.

Furthermore, there is a dearth of research incorporating structural breaks within the monetary transmission process, especially in Nigeria. Extant literature on monetary transmission mechanism (Olowofeso et al., 2014; Ogun and Akinlo, 2010; Chuba, 2015; Kelikume, 2014; Kyari and Chenbap, 2015) in Nigeria did not include structural breaks within their methodological framework. The inclusion of structural breaks in monetary policy formulation and transmission is methodologically imperative since it captures periods of structural or policy shift within the monetary formulation and transmission process. In addition, this study will examine the channels of money transmission within a structural vector autoregressive (SVAR) framework. The rationale for using the SVAR method is due to its superiority in identifying and understanding the economic relationships among the observed variables. In light of the above, it becomes expedient to examine how monetary policy channels are influenced by aggregate macroeconomic variables and to establish which channel(s) is/are more dominant on economic activity in Nigeria. This is with the view to improve the frontier of knowledge on monetary transmission mechanism in Nigeria. In essence, the objective of this study is to examine how the five different monetary policy channels respond to macroeconomic shocks within the economy and to establish the dominant monetary policy channel on output for Nigeria using a structural break and SVAR approach.

EMPIRICAL ISSUES ON MONETARY TRANSMISSION MECHANISM

This paper provides a summary of previous empirical studies on monetary transmission mechanism in developed and developing economies. Many attempts have been made to examine monetary transmission mechanism. These studies made use of VAR methods and variables such as credit to the private sector, the policy rate, exchange rate, all-share index and consumer price index as proxies for the credit channel, interest rate channel, exchange rate channel, asset price channel and expectations channel respectively. These variables served as aggregate macroeconomic variables used to represent each channel of monetary policy. Some of the earliest works were provided by Romer and Romer (1990). Their study did not find any evidence of a narrow lending point of view for the US. The paper therefore concluded that monetary policy has little influence on bank lending due to the fact that banks have alternative means of sourcing funds. Kuttner and Mosser (2002) also found a similar outcome for the US. However, Vymyatnina (2005) found that the interest rate channel and exchange rate channels were channels through which monetary policies could be transmitted into the economy of Russia, while Apergis et al. (2012) found out that output and inflation expectations affected the European Central Bank’s decision in achieving the target rate, thereby affecting lending within Europe. Finally, Fu and Liu (2015) in China found out that asymmetric effect existed when examining the monetary policy channel while there were no asymmetric effects when examining the credit channel.

In developing economies, Loayza and Schmidt-Hebbel (2002) found the interest rate channel to be the most dominant channel on output for Chile. This outcome was further boosted by studies such as Lattemae (2003), Aslanidi (2007), and Maturu and Ndirangu (2013) since they also found the interest rate channel to be the dominant channel on output for the economies of Estonia, Thailand and Kenya respectively. However, Sinclair (2004) was of the view that there were doubts on the existence of the interest rate channel in developing countries. This outcome was further reinforced by Dabla-Norris and Floerkemeier (2006) in Armenia and Aslanidi (2007) in CIS-7 countries, since their studies also found the interest rate channel to be very weak. On the contrary, Aleem (2010) found the credit channel to be more dominant on the economy of India. This outcome was further supported by Mishra et al. (2012) and Montiel (2015) for low income countries, while studies such as Mishra and Montiel (2012), Davoodi et al. (2013) gave inconclusive outcomes on monetary transmission mechanism for developing economies.

In another twist, studies such as Montiel (2013) and Gitonga (2014) found out that the policy rate exerted a weaker influence on output and prices for Uganda and Kenya respectively, while studies such as Jeon and Wu (2014) for seven Asian economies and Engler and Giucci (2015) for Moldova found that monetary transmission mechanism improved the economies of the aforementioned countries. In Nigeria, empirical studies such as Okaro (2011), Bature (2014) and Hassan (2015) found the credit channel as a very important channel of money transmission; while Bernhard (2013) and Apanisile (2016) found interest rate channel to be more dominant on output. However, Nwosa and Saibu (2012) found the interest rate and exchange rate channels as more dominant on influencing output, while Obafemi and Ifere (2015) found the interest rate and credit channel as the most dominant channels on output in Nigeria. In light of the above reviews, it is evident that monetary transmission mechanism has been a topic of discussion over the past decades; however, most of these studies majorly focus on monetary transmission mechanism and its effectiveness on real economic activity. This study will further improve this discussion by checking the impact of aggregate macroeconomic variables on monetary transmission mechanism, incorporating structural breaks in validating monetary transmission mechanism and establishing the dominant monetary policy channel on output in Nigeria.

DATA AND METHODOLOGY

This paper applied quarterly data series from 1986 to 2017 on private sector credit, consumer price index, monetary policy rate, exchange rate, all share index and real output. These data were sourced from the Central Bank of Nigeria’s (CBN) Statistical Bulletin (2017). The rationale for selecting the CBN statistical bulletin was due to its reliability and the availability of quarterly data to estimate the economic relationship among the cited macroeconomic variables. The rationale for choosing quarterly data was because they are appropriate in estimating models that incorporates structural breaks, since the periods of policy shift are better identified within a quarterly framework. Furthermore, this paper adopts a VAR approach to investigating monetary transmission mechanism in Nigeria. However, VAR models do not allow for the identification of the existing or underlying relationships that exist among the variables and hence, the structural form of the model may not be identified. An alternative framework which imposes restrictions on the range of economic relationships among the variables is the SVAR framework. This paper uses the SVAR framework in modeling monetary transmission mechanism in Nigeria in line with the underlying relationships among the variables. The restrictions that were imposed in identifying these relationships were in line with earlier studies such as Sims (1992), Christiano et al. (1999) and Davoodi et al. (2013).

The restrictions imposed in equation 1 require the policy rate to be the first variable within the model because it is the anchor through which monetary policy is transmitted into the economy. Next are private sector credits. This is because following a monetary policy shock, commercial banks delay their granting of loans by changing the loan terms (Christiano et al., 1999). Hence, credits are influenced by the policy rate. Furthermore, exchange rate is placed after the private sector credit because exchange rate responds to innovations in macro-fundamentals contemporaneously (Davoodi et al., 2013). Also, the all-share index responds to the above macro-economic variables contemporaneously, while inflation and output responds to shocks/innovations in monetary policy, private sector credit, exchange rate and all-share index simultaneously.

ANALYSIS AND PRESENTATION OF RESULTS

Presentation of results

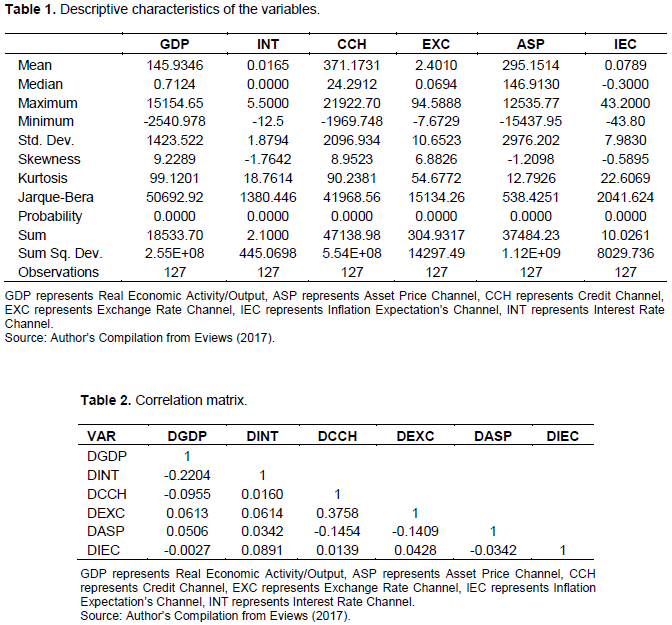

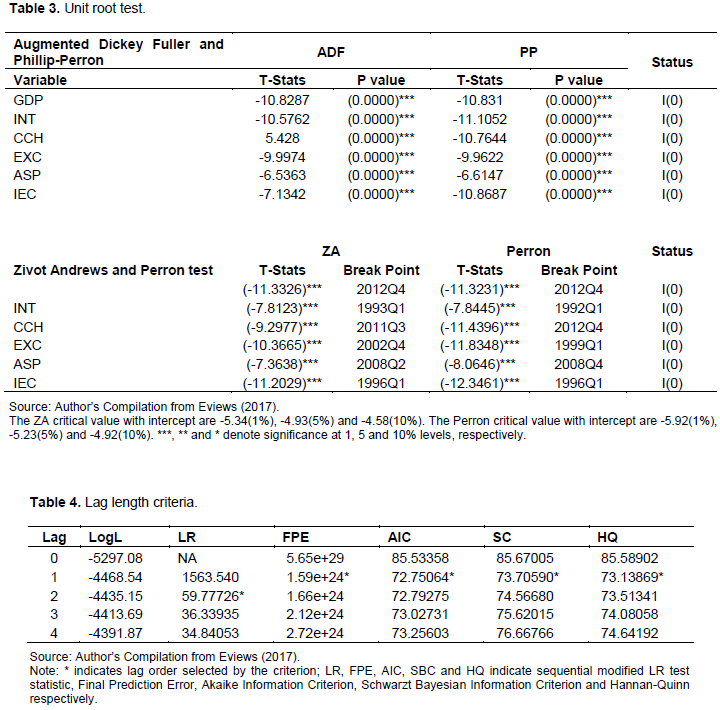

The descriptive statistic results in Table 1 showed that the mean and median values lie within their maximum and minimum values showing a good level of consistency, while interest rate displayed the least variability. The skewness statistics revealed that all the variables were positively and negatively skewed, while the kurtosis statistic all exceeded three, meaning that the series follows a leptokurtic distribution. The correlation matrix results in Table 2 showed that each variable was weakly correlated to each channel of monetary policy. Furthermore, this paper adopted both the Zivot-Andrews (1992) and Perron (2006) unit root tests in line with ADF and PP statistics since it incorporates structural breaks within the framework. The results in Table 3 confirm that the variables were stationary in their level form based on the evidences from the unit root tests. For the purpose of the analysis, the Perron (2006) structural break test results were considered due to its superiority over other methods. Finally, the study also chose a lag length of one based on the Akaike and Schwarz criteria in Table 4.

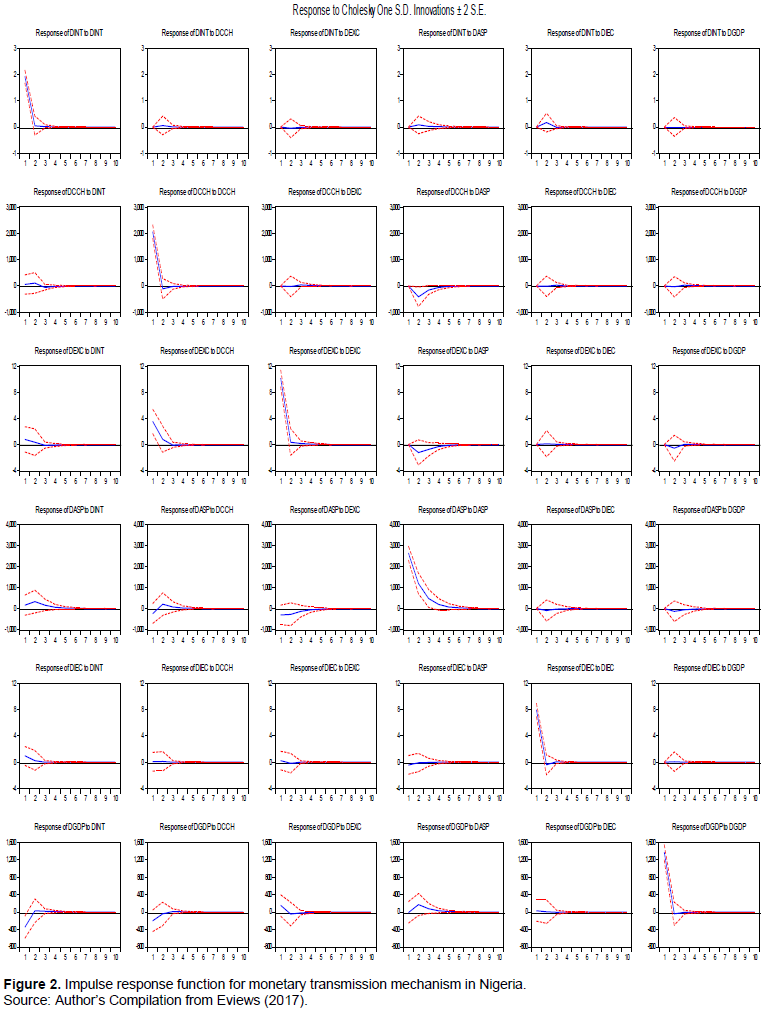

Figure 2 presents the estimated impulse response function for ten quarters. From Figure 2 (1), the result showed that a standard deviation shock originating from interest rates leads to a positive response on interest rate channel up to the third quarter. However, this shock dies out over the long term, that is, from the fourth to tenth quarter. For private sector credits, a standard deviation shock originating from private sector credits leads to a slightly positive response on interest rates between the first and third quarters. However, this response vanished over the long run since the interest rate channel did not respond to a standard deviation shock generated from private sector credits. The results of asset prices, inflation expectations and output are in line with the results generated from private sector credits. However, a standard deviation shock originating from exchange rate led to a slightly positive response on interest rate channel up to the fourth quarter, but this vanished over the long term. A major reason for this outcome may be due to the incorporation of structural break within the formulation of the analysis. The implication of this result is that the shocks derived from these variables only affect interest rate in the short term. However, in the medium to long run, these shocks vanish and the unresponsive nature of interest rate channel to shocks among the independent variables over the long run become permanent for Nigeria.

Figure 2 (2) displayed the impulse response function for private sector credits within the model. The result showed that a standard deviation shock emanating from interest rates, exchange rate, inflation expectations and output led to a slightly positive response on private sector credits for the first three quarters. However, these shocks vanished over the medium to long term since the credit channel did not respond to shocks among these variables. That is, the results show that the credit channel is affected contemporaneously by the shocks from past values of these variables in the short run but vanishes over the medium to long term. Furthermore, shocks originating from private sector credits influenced it positively for the first three quarters, but the response vanished over the medium to long term. Finally, shocks emanating from asset prices influenced the credit channel of monetary policy negatively for the first four quarters. However, these shocks die out over the medium to long term.

Figure 2 (3) shows the impulse response function for exchange rates in Nigeria. From Figure 2 (3), a standard deviation shock arising from interest rates, private sector credits and exchange rate affected exchange rate positively and led to an appreciation in foreign exchange for the first four quarters, while this shock vanished over the medium to long term. However, a standard deviation shock arising from inflation influenced exchange rates positively for the first three quarters and led to an appreciation in foreign exchange, while this shock vanished over the medium to long run. In contrast, a standard deviation shock arising from asset prices and output negatively influenced exchange rates for the first five and three quarters. However, these shocks vanish over the long term in both cases. The implication of this result is that the shocks derived from these variables only affect exchange rate in the short term. However, in the medium to long run, these shocks vanish and the unresponsive nature of exchange rate channel to shocks among the independent variables over the long run

becomes permanent for Nigeria.

Figure 2 (4), shows the response of asset prices to a standard deviation shock within the model. A standard deviation shock derived from interest rates would slightly improve asset prices for the first four quarters. However, this shock vanished over the medium to long term. Furthermore, a standard deviation shock derived from private sector credit negatively influenced asset prices in the first quarter, while this shock became positive between the second and fourth quarters. However, asset prices became unresponsive to shocks from private sector credit over the long term. Also, shocks derived from exchange rate, inflation and GDP had a negative influence on asset prices between the first five quarters. However, asset prices became unresponsive to these shocks over the long term. Finally, shocks derived from asset prices influenced asset prices positively from the short to medium term, before dying out over the long term. The implication of this result is that the shocks derived from these variables only affect asset prices in the short to medium term. However, in the long term, the unresponsive nature of asset price channel to shocks among the independent variables becomes permanent for Nigeria.

Figure 2 (5), displays the response of inflation expectations as a result of a standard deviation shock within the model. A standard deviation shock emanating from interest rate, private sector credits, exchange rate, inflation and output affected inflation expectations positively for the first three quarters only. However, these shocks on inflation expectations vanish over the long term. This implies that the expectations channel of monetary policy became unresponsive to shocks among the independent variables within the model. Finally, shocks emanating from asset prices slightly influenced inflation expectations negatively between the first two quarters, but this shock had no effect on inflation expectations between the third and tenth quarter. The implication of this result is that the shocks derived from these variables only affect inflation expectations channel of monetary policy in the short term. However, in the long term, the unresponsive nature of inflation expectations channel of monetary policy to shocks among the independent variables becomes permanent for Nigeria.

Figure 2 (6), displays the response of output to standard deviation shocks within the model. A standard deviation shock originating from interest rate and private sector credits negatively influenced output for the first two quarters and slightly influenced it positively for the next quarter. On the contrary, a standard deviation shock originating from these two variables had no influence on output over the medium to long run. In contrast, shocks emanating from exchange rate were initially positive for the first two quarters, while it became negative in the third quarter. However, shocks emanating from exchange rate vanished over the long term on output. Shocks derived from asset prices positively influenced output for the first four quarters. However, this influence vanished over the long term. Finally, shocks derived from inflation and GDP were positive on output for the first three quarters, however the effect of these shocks vanished over the long term. A major reason for this outcome may be due to the incorporation of structural break within the formulation of the analysis. The implication of this result is that the shocks derived from these variables only affect output in the short run. However, in the medium to long run, the unresponsive nature of output to shocks among the independent variables becomes permanent for Nigeria.

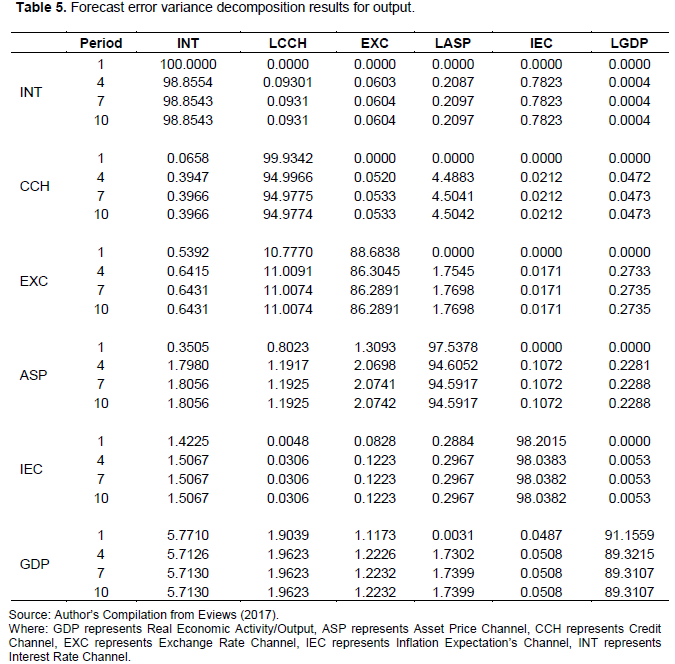

The variance decomposition result in Table 5 showed that innovations originating from the interest rate channel itself caused the greatest shock to its future value. That is, interest rate was the single source of shock on its future value in the first quarter, while it had approximately 99% shock on itself up to the tenth quarter. Exchange rate, private sector credits, asset prices, inflation as well as output account for the minor portion of shocks present on interest rates for Nigeria. The second largest source of innovations that influenced interest rates came from inflation, which accounts for about 0.78% between the second and tenth quarter. The third largest source of interest rate shocks came from asset prices and its value stood at 0.18% in the second quarter and rose marginally to about 0.21% by the tenth quarter. However, private sector credits, exchange rates and output served as the fourth, fifth and sixth source of variation in interest rates, as their values stood at 0.09, 0.06 and 0.0003% by the tenth quarter.

For the credit channel, the variance decomposition results in Table 5 showed that innovations originating from private sector credits caused the greatest shock to its future value. That is, private sector credits had the highest shock on its future value by 99.9% in the first quarter; however, this slightly reduced to about 94.98% between the sixth and tenth quarter. The remaining percentage shocks are explained by other macroeconomic variables within the model. The second largest source of variation influencing private credits was asset prices. It was 3.91% in the second quarter, and slightly rose to 4.5% between the fourth and tenth quarter. Interest rate and exchange rate served as the third and fourth sources of shocks affecting the credit channel within the model. Their values stood at 0.31 and 0.0083% respectively in the second quarter and rose slightly to about 0.40 and 0.05% by the tenth quarter. However, output and inflation served as the fifth and sixth sources of variation influencing the credit channel in the second quarter through the tenth quarter as their values respectively stood at 0.0291 and 0.0044% in the second quarter and slightly increased to 0.05 and 0.02% by the tenth quarter.

For exchange rate channel, the variance decomposition results in Table 5 showed that innovations originating from exchange rate itself caused the greatest shock to its future value; however, this dominance diminished slightly over the long term. That is, exchange rate had the dominant shock on its future value in the first quarter by about 89%, while its value dropped to approximately 86.2% between the fifth to tenth quarter. The second largest source of variation on exchange rates is private sector credits. Its value was as high as approximately 11% between the first and tenth quarter, while the third largest source of variation in exchange rates came from asset prices. A shock on asset prices would have no impact on exchange rates in the first quarter; however, this value slightly rose to 1.75% by the fourth quarter and 1.77% between the fifth to tenth quarter. This is the fourth largest source of variation in exchange rates from interest rate. The shock derived from interest rate influenced exchange rate by 0.54% in the first quarter, while it slightly increased to 0.64% between the fourth to tenth quarter. The fifth and sixth sources of variation in exchange rate came from output and inflation. A shock on output led to 0.27% change in exchange rates from the second quarter to the tenth quarter. Finally, inflation had no impact whatsoever on exchange rates in the first quarter but this changed from the second quarter as it had 0.014% impact on exchange rates. However, this value slightly rose to 0.017% between the third to tenth quarter.

For asset price channel, the results in Table 5 showed that innovations originating from asset prices caused the greatest shock to its future value. This value was as high as about 98% in the first quarter but this reduced to 94.6% between the fourth to tenth quarter. The second largest source of variation in asset prices is exchange rate. It accounted for about 1.31% in the variations affecting asset prices in the first quarter, but marginally rose to 2.07% between the fourth to tenth quarter. Interest rate and private sector credits served as the third and fourth sources of variation in asset prices during the period under observation. Their figures were as low as 0.35 and 0.80% respectively in the first quarter, but these values slightly increased approximately to 1.8 and 1.19% between the fourth and tenth quarter. Lastly, output and inflation served as the fifth and sixth sources of variation in asset prices. These two variables did not influence asset prices in the first quarter but slightly influenced asset prices by approximately 0.23 and 0.11% between the fourth to tenth quarter.

For inflation expectations, the variance decomposition results in Table 5 showed that innovations originating from inflation itself contributed to the largest shock on its future values. This value was as high as approximately 98% over the long run. The second and third largest source of variation on the future values of inflation expectations are interest rates and asset prices. Interest rates accounted for about 1.42% in the first quarter on inflation and these values slightly increased to 1.51% between the fourth to tenth quarter. On the contrary, asset prices accounted for about 0.29% in the variations on inflation expectations in the first quarter, but these figures slightly incr

DISCUSSION

From the above analysis, the impulse response results showed that a standard deviation shock originating from the observed macroeconomic variables only had a short-term impact on each monetary policy channel. In the long term, this impact vanishes, implying that standard deviation shocks affect monetary transmission mechanism and output only in the short term as earlier indicated in the body of the work. A plausible reason for this may also be due to the incorporation of structural break within the estimated model. The variance decomposition results demonstrated that innovations originating from a variable itself caused the greatest shock on its future values, while other macroeconomic variables constitute the minor innovations influencing each monetary policy channel. This outcome is plausible since the stakeholders within the monetary policy formulation and implementation process set different targets for each macroeconomic indicator. Take for instance, while the policy rate serves as the anchor on other interest rate variables, exchange rate policies have been used to manage the country’s exchange rate system, while the fear of a default have affected banks’ ability to create more loans, hence giving loans only to its trust worthy customers. The performance on the nation’s bourse – the all-share index – has also been affected by speculations within capital market activities, while expectations on future outcomes have affected prices within the economy.

In order to establish the dominant channel of monetary policy on output, the forecast error variance of each monetary policy channel on output and prices was quantitatively weighed. Observing from Table 5, it can be deduced that the interest rate channel was more prominent than any other channel of monetary policy on output. This was followed by the credit channel, which was closely followed by the asset price channel. The fourth and fifth dominant channels of monetary policy on output were exchange rate channel and inflation expectation’s channel. By implication, it can be suggested that with the consideration of structural breaks, interest rate channel is the dominant monetary policy channel on output for Nigeria. This result is in line with previous studies that also found interest rate channel to be the dominant channel of monetary policy on output both in developed countries (Romer and Romer, 1990; Vymyatnina, 2005), developing countries (Loayza and Schmidt-Hebbel, 2002; Lättemäe, 2003; Tuano-Amado et al., 2009; Maturu and Ndirangu, 2013; Gitonga, 2014; Hai and Trang, 2015) and Nigeria (Nwosa and Saibu, 2012; Bernhard, 2013; Obafemi and Ifere, 2015; Apanisile, 2016).

Finally, while monetary policy transmission seemed to function as expected in Nigeria, there is little evidence that it is able to exert powerful influence on output over the period. This is because this influence was found to be very weak since they only comprised a combined 9 to 11% on the future values of output. This outcome was in line with previous works by Kuttner and Mosser (2002) in the US and Montiel (2013) for Uganda. Consequently, an increase in money supply reduces interest rates, which reduces the cost of borrowing for firms and consumers. This leads to increased consumption as well as investment. By implication, increased consumption and investment raises aggregate demand, output and finally the aggregate price level.

CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATION

This study examined monetary transmission mechanism in Nigeria using an SVAR framework. Data on aggregate variables such as private sector credit, the policy rate, exchange rate, all-share index and consumer price index were used as proxies for the credit channel, interest rate channel, exchange rate channel, asset price channel and expectations channel respectively. The study found a significant standard deviation real effect on each monetary policy channel in the short term, while it also found that innovations arising from a channel itself caused the greatest shock on its future values. Furthermore, the study demonstrated that each monetary policy channel had a weak influence on output, with interest rate channel being the dominant channel of monetary policy on output. A major observation from this outcome was that it was in line with the theoretical expectation on monetary policy transmission mechanism since it affirms that the interest rate channel (the traditional channel) was superior in improving real economic activity in Nigeria and therefore, this channel must continue to be targeted as the major policy anchor through which monetary policy impulses are transmitted into the economy.

As a result, improving monetary policy efficiency on output will require further regulatory reforms and the strengthening of monetary policy implementation. Moreover, the monetary authorities can adopt some short-term measures to mitigate shocks and strengthen both interest rate and exchange rate channels, while the credit channel can be strengthened by tightening creditworthiness standards, strengthening accounting standards, tightening bankruptcy laws and improving corporate governance structure. These can also be done by improving bank credit assessment capabilities and strengthening the judicial system to improve the ability of banks to enforce collaterals (Nwosa and Saibu, 2012). Finally, to ensure monetary policy effectiveness through the asset price and inflation expectation channels, the monetary authorities should maintain a strong and financially sound capital market, while they maintain a low and stable inflation rate in order to improve these channels. For future considerations, monetary transmission mechanism may be examined at the micro level for Nigeria.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declared that they have no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Aleem A (2010). Transmission Mechanism of Monetary Policy in India. Journal of Asian Economics 21(1):186-197. |

|

|

Apanisile OT (2016). Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium Approach to Monetary Policy Analysis and Channels of Transmission in Nigeria. An unpublished PhD. Thesis Submitted to The Department of Economics, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria. |

|

|

Apergis N, Miller S, Alevizopoulou E (2012). The Bank Lending Channel and Monetary Policy Rules: Further Extensions. 2nd Annual International Conference on Accounting and Finance, Procedia Economics and Finance 2:63-72. |

|

|

Aslanidi O (2007). The Optimal Monetary Policy and the Channels of Monetary Transmission Mechanism in Cis-7 Countries: The Case of Georgia. Centre for Economic Research and Graduate Education 171:1-43. |

|

|

Bature BN (2014). An Assessment of Monetary Policy Transmission Mechanisms in Nigeria. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science (IOSR-JHSS) 19(3):54-59. |

|

|

Bernhard OI (2013). Monetary Transmission Mechanism in Nigeria: A Causality Test. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER 4(13). |

|

|

Central Bank of Nigeria (2011). "Understanding Monetary Policies Series, No 3 - The Central Bank of Nigeria Monetary Policy Framework. Central Bank of Nigeria, Nigeria. |

|

|

Cevik S, Teksoz K (2012). Lost in Transmission? The Effectiveness of Monetary Policy Transmission Channels in the GCC Countries International Monetary Fund WP/12/191. |

|

|

Christiano LJ, Eichenbaum M, Evans C (1999). Moneyary Policy Shocks: What Have We Learned and to What End? Handbook of Macroeconomics, eds. Michael Woodword, and John Taylor. |

|

|

Chuba MA (2015). Transmission Mechanism from Exchange Rate to Consumer Prices in Nigeria. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences 4(3):110-126. |

|

|

Dabla-Norris E, Floerkemeier H (2006). Transmission Mechanism of Monetary Policy in Armenia: Evidence from VAR Analysis. International Monetary Fund Working Paper WP/06/248. |

|

|

Davoodi HR, Dixit S, Pinter G (2013). Monetary Transmission Mechanism in the East African Community: An Empirical Investigation. IMF Working Paper WP/13/39:1-59. |

|

|

Engler P, Giucci R (2015). The Transmission Mechanism in Moldova. Reasons for its Weakness and Recommendations for its Strengthening. Policy Paper Series 01:1-16. |

|

|

Eviews 10 User Guide I and II (2017). Online: |

|

|

Fu Q, Liu X (2015). Monetary Policy and Dynamic Adjustment of Corporate Investment: A Policy Transmission Channel Perspective. China Journal of Accounting Research 8:91-109. |

|

|

Gitonga MV (2014). Analysis of Interest Rate Channel of Monetary Transmission Mechanism in Kenya. Asian Society of Business and Commerce Research, International Journal of Business and Commerce 4(04):38-67. |

|

|

Hai BV, Trang TTM (2015). The Transmission Mechanism of Monetary Policy in Vietnam: A VAR Approach. Working Paper Series IHEIDWP 15:1-35. |

|

|

Hassan A (2015). Transmission Mechanism of Monetary Policy in Nigeria: Evidence from VAR Approach. An unpublished M.Sc. Thesis Submitted to Eastern Mediterranean University, Gazimagusa, North Cyprus. |

|

|

Jeon BN, Wu J (2014). The Role of Foreign Banks in Monetary Policy Transmission: Evidence from Asia During the Crisis of 2008 to 2009. Pacific Basin Finance Journal 29(1):96-120. |

|

|

Kelikume I (2014). Interest Rate Channel of Monetary Transmission Mechanism: Evidence from Nigeria. The International Journal of Business and Finance Research 8(4):97-108. |

|

|

Kuttner KN, Mosser PC (2002). The Monetary Transmission Mechanism: Some Answers and Further Questions. Federal Reserve Bank New York Economic Policy Review, pp.15-26. |

|

|

Kyari G, Chenbap R (2015). Inflationary Process Responsiveness to Monetary Policy Transmission Mechanism in Nigeria. ISERD, pp. 5-8. |

|

|

Lättemäe R (2003). Monetary Transmission Mechanism in Estonia. Kroon and Economy No 1:58-67. |

|

|

Loayza N, Schmidt-Hebbel K (2002). Monetary Policy Functions and Transmission Mechanism: An Overview. World Bank Working Papers pp. 1-20. |

|

|

Lucky AL, Uzah CK (2017). Monetary Policy Transmission Mechanisms and Domestic Real Investment in Nigeria: A Time Series Study 1981-2015. International Journal of Economics and Financial Management 2(2):29-59. |

|

|

Maturu B, Ndirangu L (2013). Monetary Policy Transmission Mechanism in Kenya: A Bayesian Vector Auto-regression (BVAR) Approach. Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) Technical Retreat, Naivasha pp. 1-55. |

|

|

Mies V, Tapia M (2003). Monetary Policy and Transmission Mechanisms in Chile: has the Effect of Monetary Policy Changed in Time? Why? Central Bank of Chile, pp. 1- 38. |

|

|

Mishkin FS (1995). Symposium on the Monetary Transmission Mechanism. Journal of Economic Perspectives 9(4):3-10. |

|

|

Mishkin FS (2004). Economics of Money Banking and Financial Markets. 7th edition. Addison Wesley Series in Economics. USA. |

|

|

Mishra P, Montiel P (2012). How Effective Is Monetary Transmission in Low-Income Countries? A Survey of the Empirical Evidence. International Journal of Business and Commerce 4:38-67. |

|

|

Mishra P, Montiel PJ, Spilimbergo A (2012). Monetary Transmission in Low-Income Countries: Effectiveness and Policy Implications. IMF Economic Review 60(2):270-302, Published by: Palgrave Macmillan Journals on behalf of the International Monetary Fund. |

|

|

Montiel P (2013). The Monetary Transmission Mechanism in Uganda. International Growth Centre Working Paper, pp. 1-39. |

|

|

Montiel PJ (2015). Monetary Transmission in Low-Income Countries: An Overview. Employment Working Paper 181:1- 34. |

|

|

Nwosa PI, Saibu MO (2012). The Monetary Transmission Mechanism in Nigeria: A Sectoral Output Analysis. International Journal of Economics and Finance 4(1):204-212. |

|

|

Obafemi NF, Ifere EO (2015). Monetary Policy Transmission Mechanism in Nigeria: A Comparative Analysis. Research in World Economy 6(4):93-103. |

|

|

Ogun TP, Akinlo AE (2010). The Effectiveness of Bank Credit Channel of Monetary Policy Transmission: The Nigerian Experience. African Economic and Business Review 8(2):15-29. |

|

|

Okaro CS (2011). Transmission Mechanism of Monetary Policy in Nigeria. Journal of Economic and Finance, African Banking and Finance Review 1(2):1-19. |

|

|

Olowofeso OE, Bada AS, Bassey KJ, Dzaan KS (2014). The Balance Sheet Channel of Monetary Policy Transmission: Evidence from Nigeria. CBN Journal of Applied Statistics 5(2):95-116. |

|

|

Olteanu D (2015). Monetary Policy Effectiveness in Stimulating the CEES Credit Recovery. Journal for Financial Studies 19(3):8-24. |

|

|

Perron P (2006). Dealing with Structural Breaks. Palgrave handbook of econometrics 1:278-352. Retrieved from |

|

|

Romer CD, Romer DH (1990). "New Evidence on the Monetary Transmission Mechanism. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1:149-213. |

|

|

Sims CA (1992). Interpreting the Macroeconomic Time Series Facts: The Effects of Monetary Policy. European Economic Review 36:975-1000. |

|

|

Sinclair P (2004). The Transmission Mechanism of Monetary Policy in Transition and Developing Countries. Bank of England, pp.1-18. |

|

|

Tuaño-Amador MC, Glindro ET, Claveria RA (2009). Some Perspectives on the Monetary Policy Transmission Mechanisms in the Philippines. Bangko Sentral Review 09, Working Paper Series 959:18-40. |

|

|

Vymyatnina Y (2005). Monetary Policy transmission and Bank of Russia Monetary Policy. Working paper 02:1-24. |

|

|

Williams C, Robinson W (2016). Evaluating the Transmission Mechanism of Monetary Policy in Jamaica: A Factor-Augmented Vector Autoregressive (FAVAR) Approach with Time Varying Coefficients. Bank of Jamaica Working Paper. pp.1-22. |

|

|

Zivot E, Andrew DWK (1992). Further Evidence on the Great Crash, the Oil- Price Shock and the Unit Root Hypothesis. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics 10(3):251-270. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0