ABSTRACT

Rivers are a vital part of the environment as they act as habitat for several life forms, of which the well-being of many livelihoods depends for survival. Yet, the misuse of river basins in most parts of the world particularly developing countries has intensified dramatically. Appling the concept of “framing” we attempted to understand how gendered perspectives play a role in the governance of a river basin at a community level. We conducted 25 in-depth interviews over a three month period (April to June, 2017) with participants from five communities within the Tano River catchment area in Ghana. The study revealed that river-related issues at the community level continue to be framed based on some predetermined notions that have been traditionally ascribed to men and women. It was observed that the existing frames, in theory, determined whose voice is included or excluded from a decision making processes. However, the participant’s framing of roles did not reflect the specific roles women must undertake in the decision making processes at the community level. Women’s opinions are considered a second option at the local decision making level. A grey area to a social dimension in water governance indicates that women as traditionally required, delegate their opinions to men to deliver on decision platforms, and therefore it will be difficult to ensure gender equality in the management of river basins at the community level. Thus, the framing of issues at the community level plays a pivotal role in determining who participates or not in a decision making process.

Key words: Framing concept, gender roles, water governance, taboos, decision making, the Tano River basin.

Water-related issues are one of the key challenges facing humanity in the 21st Century (Peterson and Feldpausch-Parker, 2013). The Scarcity of supply, inequities in access, allocation, and use of water among various users with varied priorities have increasingly led to conflict over water at different scales (Gehrig and Rogers, 2009). At the local community level, preventing and mitigating water-related issues necessitates context-specific governance approach to water management (Gehrig and Rogers 2009; Yerian et al., 2014). Research suggests that, when participants’ interests compete over rights of the same consensus value, they spend a good deal of effort framing the values (ideals) as well as the issues (problems) (Patrick et al., 2014; Tracylee and Peterson, 2016).

Framing theorists hold the assumption that the issues and the potential significance must be brought into conformity with each other’s interest in a conflict situation. However, the applicability of the frames and its importance are often not understandable to all those involved. Furthermore the cultural environments (e.g. traditional beliefs) in some traditional communities tend to favor men’s voices over that of women and may exclude the views of the latter particularly in river related issues (World Bank, 2016). Yet, women are known to play a significant role in the management of water resources. Their traditional roles include the handling and collection of water for domestic use and agriculture (Howard and Bartram, 2003; Ray, 2007). African women traditionally have had a close affiliation with rivers and research suggests the need to include their frames in the management of water resources (Ray, 2007).

In Ghana, there are generalized issues over water supply, access, distribution, allocation and utilization of water among users. The related issues include siltation, contamination from mining and farming activities, drying up of rivers and scarcity of safe drinking water. The numbers and intensity of such water-related issues are projected to increase in the near future particularly in areas being affected by scarcity, long droughts and climate variability (Ravnborg, 2004; Wolf et al., 2005). Managing and mitigating local level water-related conflicts demands the adoption of a context-specific governance approach to address the divergent needs and concerns of local communities (Ravnborg, 2004; Wolf et al., 2005; Gehrig and Rogers, 2009). Some authors have modified the framing theory to understand different societal conditions. For example, Dewulf et al., (2011) analyzed the fragmentation and connection of frames in collaborative water governance projects in the Paute catchment and its sub-catchment Tabacay in the Southern Andes of Ecuador.

Patrick et al. (2014) used a case study from the Murray-Darling Basin in Australia to illustrate how reframing a water management issue across multiple scales and levels could help understanding stakeholders’ perceptions of justice and injustice. Additionally, Buijs et al. (2011) introduced the social representations theory as a way to understand the cultural resonance of spatial and environmental frames in the environmental conflict in the Netherlands. McLeod and Detenber (1999) included gender in their study on frame effects, nevertheless without discussing the importance of this variable. Despite the fact that several authors have contributed to the understanding of the origin of distinct social conflicts, none of them take in consideration the gender variability. Considering that the gender dimension is of extreme importance in originating variability in the social context, the present study sought to address the importance of such a variable into the “framing theory”, by studying the social issues and conflicts generated by the water scarcity in the Tano River basin, Ghana.

It is argued that with the current rate of degradation, it is reasoned that the current government approach has been insufficient in addressing the challenges facing the Tano river basin. Hence, the study was set to gain a better understanding of how participants frame issues in relation to the management of the Tano River basin whiles advancing at theoretical knowledge and uncovering of the critical areas in the governance processes of a river basin at a local level. Central to this research was “How gendered perspectives influenced resource users’ notions of river related issues at the community level”? Specifically, we addressed the following questions;

1. How are the river-related issues framed at the local community level?

2. What factors influence the framing of issues by women and men at the local community level?

3. What roles do women and men play in the decision making processes in relation to the management of the river basin?

This study employed a qualitative case study approach to explore the issues relating to the Tano River Basin. Case studies are not always useful in assessing community issues but they can be very effective in convincing policymakers of the importance of those issues and action needing (Berg, 2007). A case study is defined as “empirical enquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident, and in which multiple sources of evidence are used”, its goal is to provide a clear understanding of the issues rather than generalized findings (Yin, 2009).

Study area

The area selected for performing the study was the Tano River Basin as a case to understand how participants frame issues relating to the river. The Tano River was selected for the following reasons:

1. Major water supply for millions of people and many communities,

2. A major source of livelihoods for local communities along the river,

3. Increasing environmental concerns because of anthropogenic activities along the river and its basin,

4. Fringe Communities’ roles in the management of the river and its basin.

The Tano River Basin is located in the southwestern part of Ghana and lies between latitudes 50′N and 70°40′ N and longitudes 20°00′ W and 30°15′ N (WRC, 2012). The landscape of the Tano River Basin ranges between 0 and 700 m above sea level (WRC Ghana, 2015). The climate conditions in the area also fall partly under wet, semi-equatorial and partly under the south-western equatorial climatic zone of Ghana. The basin experiences double rainfall maxima (USAID, 2011). The Tano River is transboundary and the last 100 km downstream reaches the international boundary between Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire where it flows into the Aby-Tendo-Ehy lagoon system. The total catchment area of the Tano Basin (14,852 km2) according to the WRC (2015) is split between Ghana (93%) and Côte d’Ivoire (7%). The Tano Basin spans about 35% of the land area of Brong Ahafo region.

The Tano River basin in Ghana provides water to serve the Sunyani city and its surrounding communities. Activities of the local communities along the river basin pose serious threats limiting its potential to meet the diverse needs of the inhabitants. These activities include intensive agriculture along and within the river buffer areas, intensive use of agrochemicals and clay extraction for pottery production, deforestation, bushfires, and alluvial mining or “galamsay” (personal communication with a paramount chief, 2016). Also, the river is shrinking in width and depth as a result of siltation and settlements extension.

The diverse activities have contributed to the pollution of the water, making water treatment highly costly for the Ghana Water Company limited according to GWCL personnel (2016), posing a serious health risk to the local communities that directly use water from the river. The health sector in Ghana frequently receive reports of diseases such as typhoid fever, cholera (diarrhea), and other water borne diseases occurring amongst the inhabitants of some of the local communities (UN-GLASS Report, 2014; WHO, 2014).

Data collection

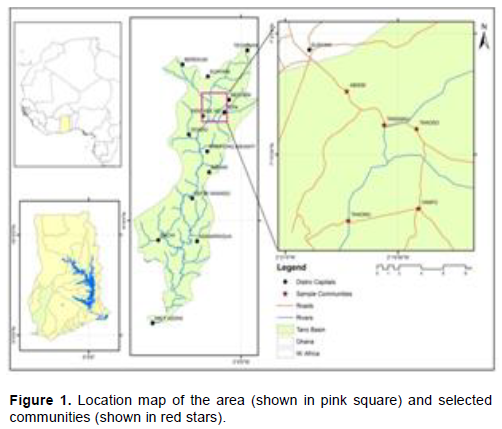

Five local communities were selected for the interviews: Abesim, Tanoso, Tano Ano, Tanomu and Yamfo communities (Figure 1). The communities were selected based on their proximity and related activities of the inhabitants within the catchment areas. The Purposive sampling method was used and a total of 25 participants (five from each community) was recruited and interviewed. The study adopted a conversation-style interview approach. The interviews were conducted in the local dialect and with an informed consent (Byrne, 2001) of the participant recorded and transcribed to facilitate data analysis.

Explaining the purpose of the study to participants before each interview was a key concern during the field work. The interviews aimed at eliciting participants views on the issues of management, decision making processes and general participation of community members in the protection of the Tano River basin. Participants were purposively sampled to include local leaders/chiefs, opinion leaders, key decision makers and farmers conducting most of their activities within the catchment area.

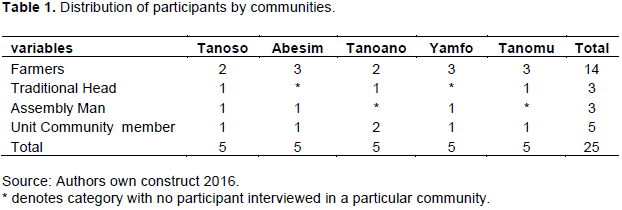

These categories of participants were considered by the researcher as those who could provide the needed data to achieve the purpose of the study. Secondly, they were considered as those knowledgeable about the area under study. Among the 25 participants, three (3) were women aged between 26 to 45 years and the remaining 22 were men. The male participants were aged between 25 to 65 years. In addition to the field interviews with participants, the researcher also carried out observations of the activities occurring within the catchment areas. This was meant to develop firsthand knowledge of some of the concerns and issues mentioned by the participants during interviews. The category and numerical distribution of research participants have been provided in Table 1.

For data analysis, a logical approach was adopted to evaluate and identify the existing patterns in the governance processes at the community level. The audio recordings of the interviews were translated and transcribed from the local dialect (that is, Twi) into English and stored as word files on a computer for the analysis to be done. Field notes included visual observations and photos of some of the human activities along the Tano River basin. The transcribed interviews were analyzed by getting familiarized with the content and identifying codes and ordering them into a list of recurring themes under which the data was to be tagged and sorted. Once these recurring themes were noted, a conceptual framework was devised based both upon the recurrent themes and answers to questions introduced to the interviewees.

Multiple sources of information in the process of achieving inquiry credibility were used (Bailey, 2007; Yin, 2009). Existing documents/ reports, in-depth interviews and observation of activities within the river were relied on to understand how frames evolved among the participants. During the data collection, some participants were revisited for the purposes of getting a better understanding of issues that were not clear after playing back to the audio recordings. This was to ensure internal validity. For the purposes of external validity, the researcher tried to include as many participants as possible. Furthermore, in the process of ensuring credibility, appropriate representation of views of the phenomenon under study was done. According to Corden and Sainsbury, (2007) and White et al., (2003), the use of quotations to represent the views of research participants in a qualitative study helps to establish credibility. Therefore, relevant quotations to represent and justify the themes were identified. For reliability, a strategy that could easily be reproduced to obtain similar outcomes when the study should be repeated in the area was adopted.

Some of the themes that emerged were traditional beliefs, taboos, women participation and gender roles. The main issues that came up from the participants during the fieldwork relied on:

1. Usage of the river and its basin by the inhabitants,

2. Degradation and siltation of the river,

3. Pollution of the river.

These issues were mainly related to the following themes: access or usage, protection and management of the Tano River basin. Participants framed the issues affecting the Tano River basin on the basis of institutional/policy failures, lack of respect for authority, and failure of traditional governance systems. The study revealed that at the local community level, there were laid down procedures for accessing and using the Tano River basin based on some traditional belief systems. For example, one of the participants explained that; “In the past, lands bordering the river about 20 to 50 yards wide belonged to the chief and no one was allowed to do anything within that area and violators were punished. But now people do whatever they like and go unpunished because they think they have a right”.

Another noticeable issue mentioned by the participants was on the pollution and siltation of the Tano River.

According to the participants, the illegal mining of alluvial gold in and around the catchment areas was affecting the flow and colour of the river hence affecting the usability of the water from the river. This issue was framed as an institutional or policy problem than one that can be solved mainly at the community or local level. Participants were of the view that, the problem required a political will and commitment to get solved. The participants framed the issue of small scale mining in the area as one that is being caused by politicians who they claim are the owners of the equipment being used. For example, a participant illustrated this by saying that;

“My brother, the machines they are using are expensive and those operating the small mines cannot afford them. They are owned by the big men (politicians) so even when you arrest them, they get bailed and go back to do it again. How can we here in the village stop such powerful people”?

This issue was mentioned by almost all the participants and they explained this by saying that;

“The main challenge of the communities was the activities of the illicit miners or “galamsay” operator around the area. When the issue of galamsey started in this area, the traditional leaders and opinion leader from the communities called on the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Regional Police Command, BNI and the Military to intervene. But we realized that even if we made arrests, the perpetrators were released without being prosecuted or even fined”.

From what the participants reported, it seems that the policy might not have been effective in regulating small-l scale mining activities, hence the challenges being faced by the fringe communities in the area. Some of the participants also framed the problems of degradation along the river based on lack of respect for traditional or local authority by the community members. They were of the view that, the young men in the communities no longer had respect for the local rules. This they blamed on the fact that some of the local authorities themselves were behind the illegal mining activities indicative of an “invisible hand” hence difficulty in curbing the problem. This revelation from the study was also an indication that governance issues at all level of society do not occur in isolation.

When asked to indicate the institution that was responsible for the management of the river basin, none of the participants mentioned the Water Resources Commission. This revelation was indicative of the fact that the authorities at the national and regional levels responsible to facilitate the policy on the management of the Tano River Basin seem to have failed in their work. Again when the participants were asked about the mining or collection of clay within the catchment area which was found to be a booming business in the area, participants again framed the issues differently. Some of the participants were of the view that the activity was affecting the river whereas some were of the view that is had no effect on the river. For example, one participant explained that;

“When they collect the clay from the area, they leave behind gullies which make working on our farms dangerous since one can fall into it. Also when it rains heavily, water collects in the gullies attracting dangerous reptiles to the areas”.

On the other hand, other participants were of the opinion that collection of clay caused no problems but rather was beneficial to the catchment. In an attempt to explain this, one participant mentioned that;

“The activity of clay collectors does not affect the river in any way. Collection of clay does not have any effect on the river. You see, if you mine clay from one area and leave to another area, the area you first mined refills naturally. This is because the areas with the clay melt to cover up the opening especially during the raining season. So the when you go back to the old sites where clay was collected, you find that the gullies have been naturally refilled. Even the clay is collected far from the river bank and not very close to the river so it does not affect the River in any way”.

Finally, river-related issues were framed based on the failure of traditional systems. According to the participants, the coming of Christianity has led to a total disregard for traditional norms. The traditional authorities themselves no longer perform rituals to appease the gods and some participants think that the gods were punishing the communities. For example, some of the participants explained that;

“We the inhabitants of the communities fringing the Tano River are not allowed to rear goats in our community. But these days there are some communities keeping goats which are against the traditional rules yet the leaders are not taking any action”.

It was revealed by the interviews that there were institutional challenges at the community level where there seem to exist a break up in the local protocols that are used to govern environmental resources. It can be argued that there is lack of coordination in institutional arrangements among the responsible sectors and the communities thereby having a negative effect on the implementation of the integrated water management approach being implemented to achieve the sustainable development agenda. The interviews further revealed some key sets of themes under which participants framed river-related issues at the community level from a gendered perspective. This study revealed that gender played a key role in the framing of river related issues by participants at the community level. Whereas women were framed as emotionally concerned individuals and good decision makers (idealistic) and they were also framed as physically weak, not strong and not good enough or “adulterated” (that is, when in their menses). To illustrate this, a unit committee member said that:

“Women are those who are more concerned about the availability of water for household use whiles men will probably be looking at their farming, irrigation and other industrial uses of water. Whiles women are thinking about household uses, men are looking at agricultural usage. When it comes to taking good care of water resources, women are always very concerned and actively involved in water related issues than the men. Women use the water for cooking, washing and bathing their children and the men use the water to grow their crops”.

Framing women as those who are more concerned about rivers and the related issues are correspondence with what Brody (2009) describes as the placing of women in “soft policy” areas. Such framing of gender roles “women” continues to keep them in a marginalized position in the broader sense. Thus, the roles women are expected to play are often shrouded by the roles they are expected to play at the household or community level which often exclude them from participating in decision making processes (Baden, 2000). Research participants also framed themselves (men) differently from the women in relation to the decision making processes at the local level. Men generally framed women as good decision makers but also framed them as weak (not strong physically) for example to arrest offenders or chasing and driving away wrongdoers. A participant explained that:

“In this community, we all have an equal say. I can admit that women are generally good at coming up with ideas, but I will tell you that the women usually stay away and allow only the men to take the action. As for me this is not good. We all have to take part so that no one feels left out. We have farmers who are men and some women so

I don’t see why the women will not take part. Everybody’s idea is important, be it from a man or woman and so is our participation in solving the problems. The problem is that the women are not strong enough to do certain things like arresting the “galamsey” miners. It is we the men who can do that so in such a case we have to do things the men way. We cannot bring in the women”.

Using physical abilities, women were framed by their men counterparts as not physically capable (strong or robust) to take part in certain river management events. A vegetable farmer and a unit committee member exemplify this by saying that:

“The cutting down of trees along the river is being done by the inhabitants (young men) of this community. You cannot blame it on anyone. Women do not engage in the logging activities because they are not strong enough to carry the logs. It is the young men who engage in it.

Participants also based their framing of river-related issues based on the kind of uses and outcomes that could result when resources are used by both women and men. Men were framed by the participants as destructive and poor management agents in terms of resource exploitation. For instance, the participant mentioned that;

“Activities of men causes more problems to the river than those of women because men are mostly involved in the mining activities and cutting down of trees along the river. Therefore we cannot leave the decision making solely in the men’s hands. They may end up destroying everything I tell you”.

Similarly, one of the participants, a farmer who has taken part in a couple of community meetings to discuss how the Tano River basin should be managed and protected at the community level in his explanation mentioned that:

“We involve women because basically most of the pollution activities that affect the river come from activities of men and not the women. The women mainly use water for household activities so they are more concerned about the water they are using”.

Meanwhile one of the participants buttressed the idea of women being physically not strong to take certain decisions yet repositories of good ideas by saying that:

“The women are very important and we have to give them the chance to also contribute. The only problem is when it comes to taking “action” then they have to be left out. The action I mean when we are to do things that demand physical strength, women I will say are handicapped. For example if we are to go and arrest the “galamsey” miners, the women cannot go because of fear of getting injured. The women are also sometimes afraid of reporting wrongdoings when they see them of fear that they may be attacked or even get beaten by the men”.

Factors influencing the framing of issues by women and men

There are several factors that contribute to framing among a group of people. The main factors that were mentioned by the participants are: Tradition, customs and taboos; socio-economic factors; and weakening traditional laws.

Traditions, customs, and taboos

Taboos are basically traditional beliefs that vehemently prohibit members of a local community from taking part in certain activities at one point in time (Crossman, 2017). Such taboos were said to have deep rooted histories behind them. The rationale behind some of these traditional laws as mentioned by the participants was to regulate the conduct of the inhabitants who lived and conducted their livelihood activities around the Tano River. An opinion leader in one of the communities pointed out some of the taboos and superstitions that surrounded the Tano River basin by saying that:

“The Tano River takes its source from a small Town close to Tachiman called Tuobodom and flows through several communities including Tanoso. The Tano River since my childhood has never run dry not even in the period of a long drought. Traditionally, the River is believed to be a human being (White Woman) and have a lot of power. She (the River) sometimes visits the community through the chief priest to announce a wrong that has been done to her and rites were performed to appease her. In the olden days, the Tano River was known for her ability to overflow its banks (flood) even in the severe dry seasons when there are no rains.

Some of the taboos that were observed in the interviewed communities were:

1. Nobody (man or woman) is allowed to use a black cooking pot to fetch water directly from the River.

2. Nobody goes to work on his or her farm close to the river on all Mondays in a week.

3. Nobody (man or woman) was allowed to farm or weed directly to the River’s bank.

4. Nobody in any of the fringe communities is allowed to keep livestock (notably goats) for any purpose.

5. A woman in her menses was not allowed to visit the River to fetch water

6. Nobody (man or woman) is allowed to fish or eat any fish harvested from the Tano River.

7. She (the River) and her children come out on Mondays so nobody goes to farm on Monday to work.

8. We don’t bath with soap in the River and we do not wash directly in the River Tano.

These taboos, according to some of the participants, were very effective in protecting the River in the past but were gradually losing their values due to the reasons as the inclusion of churches (Christian faith), increased knowledge and technological advancement, deviancy and open disregard for traditional authority/values on the part of some individuals. Two participants (village elders) who have lived in their respective communities since they were born pointed out that the traditional values and authority were being lost among the citizenry. They revealed in their explanations that:

“Currently people have advanced in knowledge, and they think they have a right and no one can tamper with their rights, so they do whatever they like disregarding our old customs. Because of that, people (farmers) now weed very close and even directly into the river exposing it to direct sunshine. You know something our ancestors were really wise people. In the past, lands bordering the river about 20 to 50 yards wide belonged to the chief and no one was allowed to do anything within that area and violators were punished. Even when someone taps wine (locally called nsafufuo or doka) from a palm tree within that area, they brought the wine to the chief’s palace. Traditionally, it meant that any resources within that demarcated (20 to 50 yards) area belonged to the chief and once something belongs to the chief, no one can go near it and this was a traditional strategy meant to protect the River. During these periods when people were adhering to these local customs, the Tano River used to flow under trees (forest areas) and it was clean for drinking and used for many other purposes”.

Social and economic factors

Men as the household heads are traditionally expected to provide for their families and therefore use all means possible to meet the demands of their families. Women according to the participants are there to cater for the family taking care of the domestic activities like fetching water, cooking and necessarily do not do things that will affect the River. For example a vegetable farmer with a family of three kids and a wife mentions that:

“Women only use water from the River for household activities and we the men use it for our farming needs. The people who engage in farming along the river (vegetable farmers) and mining of clay are mostly men. This is because of vegetable farming and clay mining activities are labor intensive and stressful and very few women can do it. But this does not mean that men do not want to protect the River. We the men are also using the resources along and within the River as a means to make an income to cater for our families”.

Dwindling prominence of traditional authority

A number of the participants pointed out that the Traditional Authorities were losing control of their authority. For example, a youth leader said that:

“The chiefs in our communities should sit-up and perform their duties. The chiefs (Ahenfo) and their elders no longer perform rituals to the River goddess and the deities (nananom) as traditionally required. These days, they only do so when there is a severe calamity in a community, for example when someone gets drowned in the River. You will be surprised that nowadays, women of all ages go swimming in the River and nobody restricts or says anything to them. At first young ladies in their pubertal age were not allowed to swim in the River except for kids. But now you see all manner of persons in the river when it is full. The chiefs and elders are sitting and watching the youth to trample on the local customs all in the name of people saying they know their right”.

Women as a second option in decision making

One of the main challenges to gender participation as revealed by the study participants was that men as well as some of the women themselves continue to see “women” as second to men particularly when it comes to decision making.

Hence much of the decisions are taken by the men without much involvement of the women. A clay product manufacturing businessman in his perspective exemplified this by mentioning that:

“I am not against the idea that women should be involved in decision making. But you have to know that I am the man of the house and some decisions I have to take them alone. Sometimes I want things to be done very fast but my wife may come up with ideas that will delay me so I don’t always get her involved in all my decisions”.

A trader and one of the three women who participated in the study mentioned that:

“Men can be stubborn at times and you know it. It is not like we (women) do not want to participate or contribute our minds when it comes to decision making. But the fact is that they are the men and the head of the house and they can do what they like. For example my husband can decide to take my suggestions on an issue but still do what he thinks is good and I cannot really say anything”.

The political connotation of issues and lack of confidence in authorities

It is common to find that political meanings are given to issues particularly when it is about decision making and representation. The interviews revealed that participants, across their respective communities, seem to be losing trust and confidence in the acclaimed representative decision making procedures both at the local and national levels. A male farmer in his interpretation said that:

“Even when we go there to say our minds, they still do what they want. They only try to create the impression that they are involving us. If you say something that is in contrast to someone’s view at such gatherings, they will only paint you with a political colour. Therefore, I don’t see the need for me to be there or to say anything that will not even be taken. They (in reference to local leaders) should do what they like”.

The overburden of women with domestic responsibilities

Traditionally women in local communities are overly burdened with house activities such as bathing their children, cooking, fetching water or making provisions for their husbands and often have less time to engage in other activities. Another female participant who is a farmer and married with two children in her submission mentioned that:

“I am a unit committee member but I usually have too much work to do in the house and I don’t have the time to attend such meetings. In this community, they usually call for such meetings on market days. They know everybody will be around to attend because we do not go to our farms on market days. But such days (time) are not convenient for some of us because a married woman with kids I have to go to the market to shop for items that we may need during the week. So my husband can attend the meeting and bring me the feedback. Even if I happen to attend, I do not speak. I sometimes attend because I am a member of the unit committee but I only do so if I don’t have much to do at home”.

Gender roles in decision making on issues related to the river at the local community level

Roles of women and men in decision making processes were not clearly indicated by the participants. For example, a cocoa farmer said:

“The participation of men and women in my opinion is very important. We are all part of the community and anything that goes wrong in the community affects us all even if not equally. Therefore taking a decision as a community is not really about men or women. Anyone who is willing to get involved is allowed to participate in the process”.

The interviews revealed that at the local community level, decisions mainly took place at the chief’s palace. The rationale behind this is that the Chief, as the head of the community, uses the palace to serve as a local court for decision making and adjudication of matters; however, there are some limitations as who is allowed to speak and who is not. The participants indicated that the decision making processes were traditionally laid out and everybody could participate in being guided by the traditional customs. An assemblyman explained that:

“We do not discriminate between men and women we only follow our traditions when making a decision. You know that traditionally there are some things or areas that women are not allowed to do or go close to in a certain time. Even this is changing because we all know the government is saying we should give equal opportunities for men and women to making decisions and so we now have women in parliament. So at the traditional level we also allow women to voice their views just that we still try to keep our traditional ways of doing things. It is not every gathering that women can actually participate in or talk”.

Conditions necessary to enhance gendered perspectives in river basin management

General views on possible measures or conditions to ensure gender participation as mentioned by the research participants were as follows: Education or awareness creation, the formation of women groups, and empowerment of women to take leadership positions.

Education and awareness creation

Creating awareness especially amongst women at the community level; thus educating them on the need for participation in decision making was much articulated by the participants. The rationale as mentioned by the participants was that customs have changed and women need to understand that they are part of the society and anything that happens in it also affects them. A male participant explains this by saying that:

“Women need to be informed that they are also important to the process of developing this community. The media people should try to say this on their radio stations for women and all other people to know that we have to come together to protect our resources. I think that a lot of people still do not know this and we all have to help in

passing on this understanding within our community. I think that educated people like you can go round communities to give out this message to the people for better understanding”.

Formation of an all-women decision making group

Formation of women associations is thought of as a mechanism that will empower women. According to the participants, women will take up leadership positions and by so they will have the courage to speak and influence decisions related to the use of the River. Forming an all women group in the communities to deliberate on water related issues was mentioned by the participants as a possible way of getting women involved in the decision making process. This opinion was expressed by two participants who in their respective views said that:

“We need to form women groups. If we have a group of women coming together, they can discuss issues and come up with possible solutions. Most at times, it is difficult for the women to speak at meetings where there are more men than women. Some of the women are shy and do not have the courage to speak at such gatherings. I will suggest that women in the communities are encouraged to form an all women group that will provide them with an environment where they can talk freely”.

In this study, we found that traditional belief systems, political affiliations, religion, and other social factors continue to play a significant role in how individuals (men and women) perceive issues related to the management of the Tano River at the community level. The study revealed that, at the local level, inhabitants still embrace the customary or traditional ways of thinking about men and women. This was clear from the participants (women) who continually referred to their husbands (men) as the heads of the family and therefore should have the greater say (valued opinion) when making a decision. This notion was very clear from the female participants who were unwilling to participate in the interviews, but rather referred the researcher conduct the interview with their husbands. This could partly be explained by the traditional norms of communities where women (principally married) are not allowed to speak to strange men visiting their community. Participants from a gendered viewpoint generally framed river-related issues under three key aspects:

Emotional perspectives, physic/physique and outcome result of using a resource On one hand, participants framed men as the agents for action (preventing wrongdoing) and on another hand as the main perpetrators of the degradation and pollution of the river. Additionally, the framing of river-related issues seem to suggest that local traditions and other belief systems continue to play a critical role in determining the responsibilities, opportunities and limitations to men and women in the decision making processes at the community level. For example, framing women as unworthy (not clean) to access water from the Tano River at a certain time can be argued as a frame that could determine women participation or not in a decision process. Again, the framing of women by their counterparts (men) as weak (not strong enough) to do certain activities as mentioned by the participants perhaps could be cited as one possible reason for women’s failures to take part in discussions concerning measures to curb illegal activities that could affect the river.

Factors influencing the framing of river related issues at the community level

Many factors may contribute to how participants frame gendered issues in relation to the decision making process in the governance of a river basin. From the current study, men framed “women” based on two perspectives. First, women were framed as more concerned about water related issues and secondly, as those who can provide valuable ideas on how the river should be managed. These types of frames as presented by the participants could partly be explained by the cultural setting of the participants.

Thus in most rural communities in Ghana, rural women usually have interactions with rivers and streams on daily basis than men. Thus on daily basis, rural women at the community level fetche water for domestic activities. These general uses of water make it a valuable resource for women, hence it could be argued as a reason for their “emotional attachment” connection to issues related to river management.

This perhaps could be said to be a reason for the kind of framing that participants had about women as being more concerned contrarily to the latter. Again, women in their demand for water require it, in its best, clean and usable form and anything short of this affects them. It was however not surprising that this study found that women were framed differently by the men in relation to issues on the management of the river at the community level.

Furthermore, in a society (cultural environment) where traditional beliefs systems continue to play a key role in determining “who does what and what not”, it can be argued that such realistic assumptions as equal rights for men and women as mentioned by the Un-water (2012) still remains unfounded and cannot be overemphasized. This is because, in most African traditional local communities, there are still differentiated or definitive roles for ‘women’ and ‘men’ as well as limits or restrictions to who can or cannot participate in a decision making at the local level (Cap-net and Gwa, 2006).

Thus, notwithstanding the global advocacy for equal representation of women and men in the decision making processes at all levels of society, this study has revealed that women participation continue to remain a challenge at the local level due to factors such as traditional belief (taboos) systems, socio-economic factors; overburdening of women with household activities and women’s own prejudices of themselves as second to men in decision making. The participation of women in decision making may be narrow-minded by what Foucault (1982) and Bhopal, (1997) conceived as acquiescence, patriarchy or ‘cultural messages’. Such prejudices prompt women to view themselves as cautious, self-doubting and lacking the right or power to decide or contribute to a decision- making the process most at the various levels of society (O’Grady, 2005; Cornwall, 2008; 2012; 2014). This argument is analogous to Foucault’s conception of a ‘normalizing gaze’ in which participants (in this case woman) may behave in certain ways because men framed them differently.

Despite the rhetoric of gender inclusion and as a matter of fact legislative provisions for gender inclusion in the of governance river basins (Section 6.2 of the Tano Basin Management Plan) (WRC, 2012), this study revealed that a number of impediments exist particularly for women to be recognized as key players in decision making at the community level. A major hindrance to ‘women’ participation as established in this study was the stereotyping of certain activities as “men’s job” as indicated by some of the participants in the interviews. According to Cleaver and Hamada (2010), such stereotypes in a society possibly have the potential to sideline some actors (e.g. women) and to make them seem less important to the decision processes and hence their non-participation in the related activities.

Gender roles in decision making on issues related to the river at the community level

Gender roles are activities ascribed to women and men on the basis of their perceived differences. These roles tend to vary across cultures and communities and are time bound. Understanding gender roles is an important facet of resource governance because decisions must address the needs as well as the concerns of both men and women (Asaba and Fagan, 2015). Differentiating roles between men and women (that is, what women can do or cannot do) was evident among the participants who also correspond to the argument by Nang and Ouch (2014).

In their study, Nang and Ouch argued that contextualizing gender roles is a common phenomenon across many societies regardless of race, gender, age, class and/or ethnicity. The study showed that men and women traditionally framed different roles, challenges and control in terms of the governance processes (decision making) at the community level. From the study, the framing of men as the heads or authority at the household and community level gave them more opportunity to be involved in the decision making processes hence played a significant or conspicuous role than the women. It was evident that at the local or community level, men took control over the management, use and resolving of water-related issues more than women did. Based on this observations, it is argued by this study that women (as well as their views) are being pushed into a more weakening position (relegated to the foreground) or ‘excluded’; allowing the men to provide perhaps exclusive inputs and conclusions on water- related decisions in their communities.

The observations from this study were in correspondence with the argument of Tandrayen-Ragoobur (2014). In a study on gendering governance in Mauritius, Tandrayen-Ragoobur argued that perceptions of the roles women and men play in a society as well as their access to rights and resources are often embedded in the decisions made and policies that are implemented by governance institutions at all levels. From this study, gendering roles of women and men in relation to river related issues at the community level were found to be based on traditionally preconceived meanings that have been given to men and women. Such preconceptions were found to be the issue defining frames that determined what men and women can do in terms of managing and taking decisions on the river basin at a community level. This seems to be the reason why there are still fewer women than men that take part in decision making positions at the local level of governance (Tandrayen-Ragoobur, 2014).

This current study further revealed that the participants (mostly men) support more women participating in the decision making processes particularly at the local level. The male participants in this study generally framed gender (women) and water-related issues from an optimistic perspective. These revelations from the study were in congruence with the arguments of Nang and Ouch (2014) who in their study posited that women have a deeper understanding of issues that affect water and can help resolve some of the critical issues better than men in perhaps a better, fast and peaceful manner. This study has also shown that gender plays a key role in framing issues concerning the use and management of a river and its basin. Thus women and men were found to have different frames thereby affecting how they orient their thoughts about the issues of the local community.

The general assertion by the participants in this study and the need to support the participation or inclusion of views and voices of both, women and men, in the decision making processes confirms the argument of Nang et al. (2011), That is, for a realistic or representative water governance process to occur and prevail, equal participation of women and men in the decision making processes at the community level is essential and should be embraced. Observations and revelations made by the participants during the interviews, however, seem to contradict this assertion by Nang et al. (2011). This is because the women in the local communities generally refrained (shied away) from participating in the interviews sessions. It was, however, assumed that local women still frame themselves unqualified in contributing to decisions which could be attributed to reasons that this study could not address. Cleaver (2000) suggests that how people frame the world around them also affects how far they are prepared and able to participate in and influence decision-making arrangements.

In a situation where traditional beliefs play a significant role, people frame their own actions as interconnected to the natural and supernatural world and such views according to Cleaver and Hamada (2010) are often gendered. It is argued that women at the community level may have adopted frames meant to excuse themselves from taking up extra responsibilities in addition to those they are expected traditionally to handle. This argument is in consonance with Dikito-Wachtmeister (2000) who studied the reasons for women participation or non-participation in water projects in Zimbabwe and found that women’s beliefs in the existence of witchcraft shaped their willingness to partake in community decisions or not in matters of water management. However Dikito-Wachtmeister (2000) further distinguished that such frames on the part of some community members could also be a strategy to excuse themselves perhaps from time consuming water decision processes.

This notwithstanding, it is posited that when women and men in the communities fringing the Tano River basin work collectively, by sharing views through decision making processes, it could perhaps imply the creation of equal opportunities and responsibilities in contributing their views on water resources management issues. It is mentioned here that when men and women share thoughts by working together in planning the uses, access and control over the water resources, it will create a sense of ownership and responsibility among the individuals (Tracylee and Peterson, 2016).

This argument is partly supported by the Un-water (2012; 2005) in their assertion that when women and men work collectively, it creates the opportunity for addressing their specific needs as well as addressing their concerns. Perhaps when this happens, women in local communities will take decisions equally alongside their men counterparts to effectively and sustainably govern the resources in their communities.

Conditions necessary to enhance gendered perspectives in the management of the river and its basin

Usually, socially constructed ideas tend to create unequal power distribution relations amongst men and women, with men in domination (included) and women in subordination (excluded). The necessary conditions mentioned by the participants were public education or awareness creation, the formation of women groups and the empowerment of women to take leadership positions. The main problem with gender mainstreaming strategies particularly in a decision-making process could be the problem of a top-down approach to governance at all levels of society. The strategies as indicated by the participants can be argued to key governance areas that have seen a lot of criticisms in terms of representation of gender. These measures also correspond with the existing literature (For example, CAP-NET, GWA (2006) on gender studies which have indicated the need for empowering women through education and other support channels to enable addressing gender-related issues in our society.

Thus to achieve “equal” participation of women and men, the social order (societal way of thoughts) need to be purged by reconstructing our thoughts about ‘men’ and ‘women’ as has been predetermined by existing local customs, cultures or traditions (Amenga-Etego, 2003). It is posited that the formation of an all women groups, mass education of the general public and encouraging women by putting them in leadership roles could offer the advantage (opportunity) for women to participate without hindrances. Secondly, education, the formation of women groups and empowerment of women to take leadership positions perhaps have the potential to improve the quality of women’s participation. Thus for women who are generally unfamiliar to taking up positions of authority, it is argued that considerable groundwork as indicated by CAP-NET, GWA (2006) may be needed for women to develop their self-confidence, assertiveness and skills necessary for dealing with the already established societal orders at the decision making level.

Finally, the non-participation of women in decision- making processes could also be attributed to the working arrangements of the governance processes of the community. Thus, the timing, scheduling and duration of decision making meetings at the community may not be flexible for women to double with their additional traditional or household responsibilities that they are often expected to take on (Tandrayen-Ragoobur, 2013).

Overall, it revealed that participants framed river related issues based on subtle viewpoints. This tends to determine the full participation of women in river basin management initiatives. However, the optimistic framing of women by men as revealed in this study did not reflect the specific roles of women in the decision making processes as women still leave the decision making in the hands of the men. Traditional beliefs, socioeconomic and domestic responsibilities of women and men were found to be some of the main factors that influence participants foaming of issues and thereby their participation in decision processes at the local/rural community level.

Gender roles though not well defined seem to be differentiated among men and women at the community level and men continue to dominate the processes of decision making. The study revealed that the participants were adequately informed about the measures or steps that could be taken to address the issue of women participation in decision making. It established that the gender dimensions in framing issues at the local community level have the potential to influence who participates in a decision process or not. Thus current river management processes at the community level can be engineered to address gendered issues with respect to the management of a river basin.

Finally, this has brought to the facade a significant area for future research consideration where researchers must endeavor to take a critical look at the issues affecting women’s and men’s participation in decision making to address their needs, challenges and varied concerns based on the legislative requirements that have been laid out in policy documents. Such information will be valuable for a critical evaluation of the countries performance in terms of achieving Millennium Development Goal 3 to: Promote Gender Equality and Empowerment Women.

We recommend a future analysis of the natural resource governance processes with particular focus on river bodies, protected areas and the linkage between these and food security in the catchment communities paying specific attention to climate change effects and adaptive capacities of the local inhabitants in these local communities.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Amenga-Etego R (2003). Water Privatization in Ghana: Women's Rights under Siege. Case Study Commissioned by UNIFEM for the 2003 World Social Forum. New York: UNIFEM, 2003.

|

|

|

|

Asaba RB, Fagan GH (2015). Women Water-keepers? Women's troubled participation in Water Resources Management. In: Munck, R., Asingwire N, Fagan H, Kabonesa C (Eds). Water and Development: Good Governance after Neoliberalism. New book in the CROP International Studies in Poverty Research Series, London, Publishers ZED Books

|

|

|

|

|

Berg B (2007). Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences (6th Edition). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.

|

|

|

|

|

Bailey CA (2007). A guide to Qualitative Field Research (2nd Edition). Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA (2007) pp. 214

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bhopal K (1997). Gender, 'Race' and Patriarchy, Aldershot: Ashgate.

|

|

|

|

|

Byrne M (2001). The concept of Informed Consent in Qualitative Research. AORN Journal 74(3):401-403.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Buijs AE, Arts BJM, Elands BHM, Lengkeek J (2011). Beyond environmental frames: The social representation and cultural resonance of nature in conflicts over a Dutch woodland. Geoforum 42:329-342.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

CAP-NET GWA, (2006). Why Gender Matters: a tutorial for water managers. Multimedia CD and booklet. CAP-NET International Network for Capacity Building in Integrated Water Resources Management, Delft.

|

|

|

|

|

Cleaver F, Hamada K (2010). 'Good' Water Governance and Gender Equity: A troubled relationship. Gender and Development 18(1):27-41.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cleaver F (2000). 'Moral ecological rationality, institutions and the management of common property resources', Development and Change 31(2):361-383.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cornwall A (2003). 'Whose voices? Whose choices? Reflections on Gender and Participatory development', World Development 31(8):1325-1342

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cornwall A (2008). "Unpacking Participation: Models, Meanings and Practices." Community Development Journal 43:269-269.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cornwall A (2012). "Framing women in international development" presentation at Development Studies Association, London, November 2011.

|

|

|

|

|

Cornwall A (2014) 'Strategies or pathways to make states more accountable for women's rights', Background Paper prepared for UN Expert Group Meeting, 'Envisioning Women's Rights in the Post-2015 Context', New York, 3–5 November 2014.

|

|

|

|

|

Crossman A (2017). Understanding Folkways, Mores, Taboos and Laws. Retrieved October 10, 2017 from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Corden A, Sainsbury R (2007). Exploring 'quality': research participants' perspectives on verbatim quotations. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 9(2):97-110.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dewulf A, Mancero M, Cárdenas G, Sucozha-ay D (2011). Fragmentation and connection of frames in collaborative water governance: a case study of river catchment management in Southern Ecuador. International review of administrative sciences 77(1):50-75.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dikito-Wachtmeister M (2000). 'Women's Participation in Decision Making Processes in Rural Water Projects, Makoni District, Zimbabwe', unpublished Ph. D. Thesis, University of Bradford, UK

|

|

|

|

|

Foucault M (1982). 'The Subject and the Power', In: Dreyfus, H.L and Rabinow, P. (Eds.), Beyond Structuralism and Hermeneutics, Chicago IL: University of Chicago Press pp. 208-226

|

|

|

|

|

Gehrig J, Rogers MM (2009). Water and conflict incorporating peacebuilding into water development. Catholic Relief Services, United States Conference of Catholic Bishops, Baltimore.

|

|

|

|

|

UN-GLASS Report (2014). Investing in water and sanitation: increasing access, reducing inequalities. UN-water global analysis and assessment of sanitation and drinking water.

|

|

|

|

|

Howard G, Bartram J (2003). Domestic water quantity, service level and health. World Health Organization, Geneva

|

|

|

|

|

McLeod D, Detenber B (1999). Framing effects of television news coverage of social protest. Journal of Communication 49:3-23.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nang P, Khiev D, Philip H, Isabelle W (2011). Improving the Governance of Water Resources in Cambodia: A Stakeholder Analysis. Understanding Stakeholders' Roles, Perceptions and Constraints for Effective Irrigation and Catchment. Working Paper 54(Phnom Penh: CDRI).

|

|

|

|

|

Nang P, Ouch C (2014). Gender and Water Governance: Women's Role in Irrigation Management and Development in the Context of Climate Change. Phnom Penh: CDRI.

|

|

|

|

|

Patrick MJ, Syme, JG, Horwitz P (2014). How reframing a water management issues across scales and levels impacts on perceptions of justice and injustice. Journal of Hydrology 519(2014) 2475–2482

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Peterson TR, Feldpausch-Parker AM (2013). Environmental Conflict Communication In: Oetzel JG, Ting-Toomey S (Eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Conflict Communication: integrating theory, research, and practice, second edition. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks pp. 513-535.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ravnborg HM (2004). Water and conflict: conflict prevention and mitigation in water resources management. Danish Institute for International Studies, Copenhagen.

|

|

|

|

|

Ray I (2007). Women, Water and Development. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 32:421-449 .

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tracylee C, Peterson TR (2016). Environmental Conflict Management. SAGE Publications Inc.

|

|

|

|

|

Tandrayen-Ragoobur V (2014). "Gendering governance: the case of Mauritius", Equality, Diversity and Inclusion: An International Journal 33(6):535-563.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

UN-WATER (2005). Gender, Water, and Sanitation: A Policy Brief. Water for Life 2005-1015 (UN-WATER),

View (accessed 24 June 2016)

|

|

|

|

|

UN-WATER (2012). Gender, Water and Sanitation (UN-WATER),

View (accessed 24 June 2016)

|

|

|

|

|

United States Agency for International Development (USAID) (2011). Biodiversity and tropical forests environmental threats and opportunities for assessment. Retrieved from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Water Resources Commission, Ghana (2015). About us. Retrieved June 25, 2016, from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Water Resources Commission, Ghana (2012) Annual Report 2012. ISBN: 978-9988-8237-1-9. Available at

View Date accessed 02/08/2016

|

|

|

|

|

Water Resources Commission, Ghana (2011). Gender and Water Resources Management Strategy. Available at

View date accessed 02/08/2016

|

|

|

|

|

White C, Woodfield K, Ritchie J (2003). Reporting and presenting qualitative data. In: J. Ritchie and J. Lewis (Eds.), Qualitative Research Practice: A Guide for Social Science Students and Researchers, London: Sage pp. 287-320.

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (WHO) (2014) Preventing diarrhea through better water, sanitation and hygiene. World Health Organization, Geneva.

|

|

|

|

|

Wolf A, Kramer A, Carius A, Dabelko G (2005). Managing water conflict and cooperation. In: Stark L (ed) State of the world 2005: redefining global security. The Worldwatch Institute, W.W. Norton and Co, New York pp. 80-99

|

|

|

|

|

WRC/CSIR-WRI (2010). Catchment-Based Monitoring Project Report (December 2010).

|

|

|

|

|

World Bank (2016). Key issues on gender and development. Retrieved from

View (date accessed 31 August, 2016)

|

|

|

|

|

Yerian S, Hennink M, Greene EL, Kiptugen M (2014). The Role of Women in Water Management and Conflict Resolution on Marsabit, Kenya. Environmental Management 54:1320-1330.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yin R (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

|

|