ABSTRACT

Unsustainable human activities and climate change are threatening the sustainability of coastal ecosystems in countries of West-Central Africa. This paper advocates that focusing on mangrove ecosystem management can potentially mitigate these threats by pointing out clues on management orientations and opportunities for other coastal systems. This article elucidates this point by using evidence from informal interviews with stakeholders and expert-led literature reviews to assess mangrove conservation interventions implemented between 2000 and 2014 across countries of West Africa and Cameroon. Results show that many institutions are taking actions in countries of West Africa and Cameroon to conserve and restore mangroves. These interventions may be slowing down the rate of mangrove forest loss across West-Central Africa. However, this recovery does not appear to be benefiting other coastal ecosystems. This unequal distribution may be linked to the increasing challenges plaguing coastal ecosystems management, and hence the effectiveness of mangrove conservation efforts in this region. These problems are both internal and external to institutions, undertaking targeted interventions. External challenges are beyond the control of implementing organizations and synergize with internal institutional deficiencies to impede overall coastal ecosystem sustainability. Improving overall coastal ecosystems sustainability in this region will, therefore, require a coordinated approach between all stakeholders that are directly or indirectly influencing coastal ecosystems. In this regard, practitioners need to improve the effectiveness of traditional conservation practices, expand conservation efforts and funding mechanisms as well as develop integrated strategies that encompass all activities that affect coastal ecosystems, in a vertical and horizontal manner.

Key words: Mangroves, coastal ecosystems, conservation effort, conservation challenges, ecosystem services.

A coastal ecosystem is a collection of habitats often located along the continental margins of the world. They include; coastal forests, coral reefs, estuaries, lagoons, marine-water, salt marshes, sandy beaches, rocky shores, and mangrove forests amongst others. Environmental variables and geographic location determine the global distribution of coastal ecosystems habitat types. For instance, mangroves are limited to the tropical and sub-tropical regions of the world (Spalding et al., 2010). Coastal ecosystems are among the most productive globally, and their values have been extensively studied (Spalding et al., 2010; Baba et al., 2013; UNEP, 2014). Across some coastal countries of West Africa (Senegal, The Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Benin, Nigeria) and Central Africa (Cameroon), coastal ecosystems have been assessed to provide a broad range of socio-economic and ecological services to various stakeholders (UNEP, 2007; Nwilo and Badejo, 2005; UEMOA and IUCN, 2010; Diop et al., 2014). However, poor policies and open management practices by stakeholders within these coastal ecosystems are promoting their degradation and depletion (Diop et al., 2006; FAO, 2007; Feka et al., 2009; Feka and Ajonina, 2011).

These transformations threaten and risk the very existence of these ecosystems and the livelihood strategies of millions of vulnerable coastal communities; who depend on them for subsistence and posterity (UNEP, 2007; Nwilo and Badejo, 2005; IUCN and UEMOA, 2010; Diop et al., 2014). Moreover, the effects of these ecosystem transformations are compounded by climate change, suggesting far-reaching socio-economic and ecological consequences in countries of West Africa and Cameroon (Abe et al., 2002; de Lacerda, 2002; Ellison and Jouah, 2012; Munji et al., 2013). Against these threats and risks to both the environment and the proximate human communities, it is imperative to identify and promote conservation solutions that can adequately address these issues, without compromising a sustainable supply of ecosystem services to humankind.

Various biodiversity conservation strategies have been developed to support the sustainability of coastal ecosystems with mixed results (FAO, 1994; McClanahan et al., 2005; Diop et al., 2006; McClennen and Marshall, 2009). Amongst these is the use of the ecosystems-based conservation approach, which is gaining wide acceptance in global political agendas as a sustainable option with various co-benefits and which can be used to reduce pressures resulting from both anthropogenic activities and climate change (CBD, 2009; Munang et al., 2013). This strategy is particularly relevant to most developing countries because they lack the capacities and technologies for more intensive approaches to climate change mitigation (IPCC, 2007). Land Use and Land Use Change and Forests (LULUCF), [of which mangrove forests are a subset] is one of the cheapest climate change adaptation and mitigation options (Stern, 2006). The conservation of mangroves and their constituent habitats is already being employed to address climate change and anthropogenic pressures across East Africa, Madagascar and South-East Asia (Fischborn and Herr, 2015; Wylie et al., 2016). Although this research is still in the preliminary stages, focusing on mangrove management to guide the overall sustainability of coastal ecosystems would be widely beneficial, because of the connecting, provisioning, supporting and regulatory services mangrove ecosystems provide to other coastal habitats, their biodiversity, and vulnerable human communities.

Therefore, careful management of mangrove forests may be beneficial by to the broader coastal ecosystem landscape by providing clues on management orientations and opportunities for intervention (Blasco et al., 1996; UNEP, 2014; Alongi, 2014; Ellison, 2015). Evidence of this guiding role is shown by the increasing number of studies that correlate the state of mangrove health to the well-being of other coastal habitats and biodiversity. This role is further seen, for instance, in the link between mangrove forest degradation and drop-offs in fish and crustacean productivity. The dieback of mangrove trees is tied to changing water nutrient and temperature levels, while the alteration of mangrove zonation patterns influences species composition. In addition, mangrove forest depletion exposes the coastline and hence exposure to erosion (Blasco et al., 1996; McClennen and Marshall, 2009; Brenon et al., 2004; Adite et al., 2013; Das and Crépin, 2013; Hutchison et al., 2014; Worm et al., 2006; Hutchison et al., 2014; Ellison, 2015). These linkages imply that any significant changes in the state, health, population structure, species composition, location and chemistry of the mangrove ecosystems could serve as important bio-indicators of changes to other coastal habitat variables.

The management of mangrove ecosystems has been marginalised in political agendas across Africa and many other developing regions of the world for a very long time (CEC, 1992; Van Lavieren, 2012; Feka, 2015). However, the last two decades have seen a worldwide proliferation of mangrove conservation initiatives in coastal West Africa and Cameroon (USAID, 2014). Increasing interest in mangrove conservation is fuelled by improved scientific understanding of the ecological and climatic services, coupled with the socio-economic values of the goods and services derived from this ecosystem (Macintosh and Ashton, 2002; Adekanmbi and Ogundipe, 2009; Ajonina, 2010; Diop et al., 2014; Osemwegie et al., 2016). Despite these values, mangroves remain the most vulnerable tropical ecosystem globally (Spalding et al., 2010). These recognized values and threats are prompting growing international commitments to manage and sustain mangrove forests (Alongi, 2008; Van Lavieren et al., 2012; UNEP, 2014; IUCN-MSG, 2014).

As is the case with most tropical ecosystems, the sustainable management of mangroves in countries of West-Central Africa is constrained by the lack of funding, scarcity of adequate data to facilitate informed decision-making, and restrictively short project financing time-frames in which to design and implement feasible solutions (BSP, 1993; FAO, 2007). These factors are at the center of failures in conservation initiatives in most developing countries, particularly because they undermine stakeholder expectations and promote poor conceptualisation of issues. Lack of funding and data may lead to inadequate or wrong mangroves and coastal ecosystem management strategies (FAO, 1994; Feka, 2015). Therefore, it is imperative that governments, national institutions, and international aid agencies with interest in the development of coastal ecosystems across West Africa and Cameroon learn from previous mangrove conservation initiatives experience which will support the scaling-up or implementation of new coastal ecosystem conservation interventions (USAID, 2014). Region-specific data is scarce for this region (Armah et al., 1997; Kjerfve et al., 1997; Diop et al., 2006). Additionally, when available, this knowledge will help guide funding and aid agencies to the most productive and sustainable investment options and will inform and improve prospective implementation strategies by orienting efficient use of resources for effective results. Extensive research and knowledge sharing on coastal and mangrove ecosystem in East Africa and South East Asia has led to the development of strategic management plans for mangroves and other coastal systems (FAO, 1985; Chan and Baba, 2009; Spalding et al., 2010; Van Lavieren et al., 2012; Fischborn and Herr, 2015; Wylie et al., 2016). This research concentration and the knowledge-sharing environment has also produced some of the most highly regarded experts in mangrove and coastal ecosystem management. The availability of extensive information/data and knowledgeable specialists is attractive to long-term investors supporting conservation of coastal ecosystems across South-East Asia and East Africa. Consequently, these regions have already seen a reversal in mangrove forest loss (Aung et al., 2013; Giri et al., 2014).

Unfortunately, current regional information/data from previous mangrove conservation initiatives in countries of West Africa and Cameroon is dispersed, scarce or not readily available to support planning for mangrove and coastal ecosystem management. Even when available, such information is incomplete, fragmented or exists just as an account of independent research initiatives rather than a strategic regional perspective (Kjerfve et al., 1997; Diop et al., 2014). This study thus aims to promote the sustainable management of coastal ecosystems, by presenting the experiences and challenges of implementing mangrove conservation interventions in some of the coastal countries of West Africa and Cameroon between 2000 and 2014. Specifically, to (i) assess mangrove related research and progress towards the development of a legal framework for mangrove ecosystems management, (ii) determine intervention(s) implemented between 2000 and 2014 to highlight lessons, and (iii) examine how externalities are collectively challenging coastal ecosystem conservation efforts across countries of West Africa and Cameroon. The results of this study will radically re-shape the way coastal ecosystem interventions should be designed in the future. It will be a valuable resource to international development agencies, government and national organisations seeking to invest in the management of coastal ecosystems of West Africa and Cameroon. Project managers and researchers will benefit from the lessons learned, and the extensive bibliography on mangroves and coastal ecosystems of the region as documented in this study.

Study areas

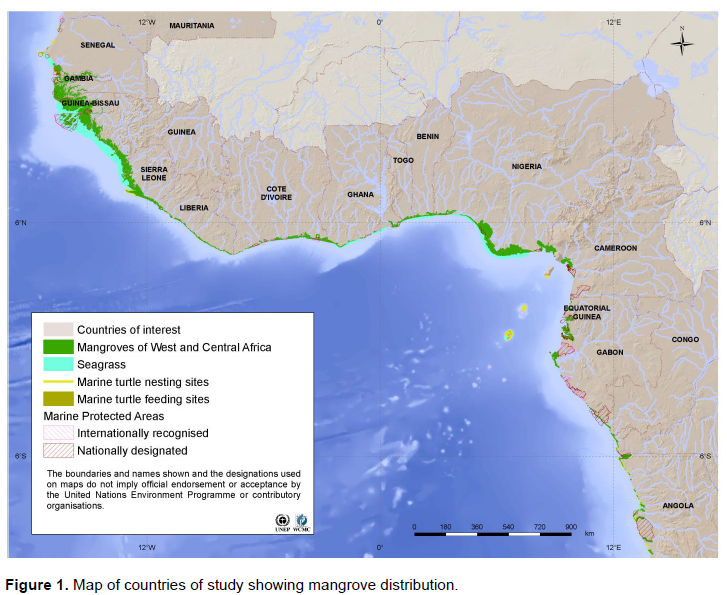

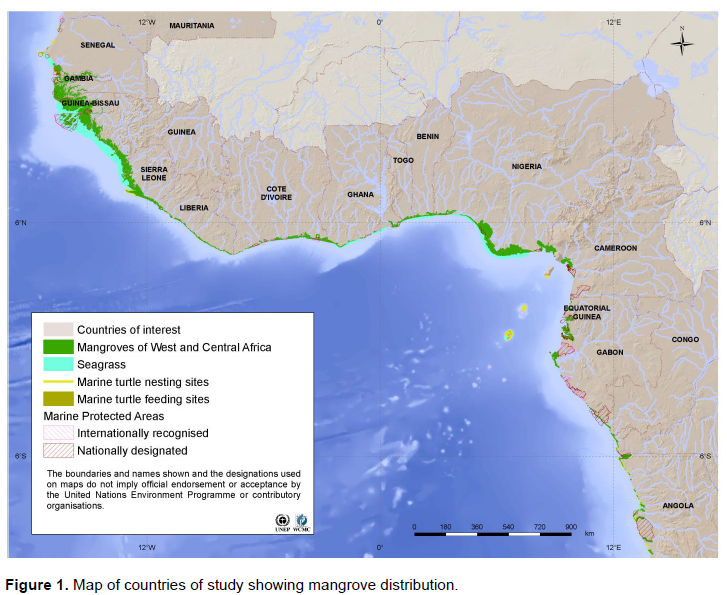

The study was carried out from February 2014 to February 2016. It focused on coastal ecosystems, with an emphasis on mangrove forests. Study sites were selected using the following criteria: (1) Biological significance, such as harbouring regionally or nationally important biodiversity or essential nesting or spawning grounds; (ii) Potential to sequester significant amounts of carbon with improved management, and (iii) Inclusion in national or regional adaptation plans as an area where human populations will feel great stress from climate change. Shortlisted countries included; Senegal, Gambia, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Benin Nigeria and Cameroon (Figure 1). Cameroon was included because of the region’s extensive experience in mangrove ecosystem research and management.

The morphology of the coastline of the selected countries, and the different ocean currents, which influence continental fisheries, are widely reported (Kelleher et al., 1995; UNEP, 1999; Feka, 2007). Along with this coastal margin, several rivers drain from the hinterland into the Atlantic Ocean along this West African and Cameroon coastline, creating suitable conditions for the development of about 19,581.0 km

2 of mangrove vegetation dispersed over 4710.0 km across these countries (FAO, 2007). The mangroves establish along creeks, bays, estuaries, and major rivers towards the hinterland. The established mangrove vegetation is complex in structure, with trees generally decreasing in size as the salinity increases from Cameroon (low mean salinity of [16%] and high main rainfall [4000 mm year

-1] levels), towards Senegal’s high mean salinity of 26% and low mean annual rainfall of 1800 mm (Godstime et al., 2013; Tening et al., 2014; Sakho et al., 2015). Established mangroves are cumulatively made up of nine re

[1] Mangrove tree species across countries of the region, with no significant variation in species numbers between countries (UNEP, 2007; FAO, 2007; Essomè-Koum et al., 2012). These mangroves establish on sheltered sedimentary coastlines, with soft muddy substrates, under anaerobic conditions. These muddy soils are formed from continuous interaction between the processes of sedimentation and erosion along this coast (UNEP, 1999; Diop et al., 2014). The growth and development of mangrove plants is influenced by large masses of warm water (above 24°C) and a generally low average salinity (less than 35‰) because of high levels of precipitation and freshwater from numerous rivers that discharge into the Atlantic Coast also contribute to the flourishing of mangroves in this region (Tening et al., 2014).

Ecological characteristics at this environmental edge of West Africa and Cameroon, create favourable environmental conditions for various resident, migratory and endemic species. For instance, the West African manatee (Trichechus senegalensis), the globally endangered pygmy hippopotamus (Choeropsis liberiensis) found in the coastal forests of Liberia and the Niger Delta, and numerous cetaceans including; the humpbacked whale (Megaptera novaeangliae), sperm whale (Physeter microcephalus), bottlenose dolphin (Tursiops) and humpback dolphin (Sousa) who use the warm coastal waters of the region for reproduction and migration. Also, the threatened Pennant’s red colobus monkey is found in the isolated forests of the Niger Delta and Bioko, while the Dwarf crocodile and slender-snouted crocodile thrive in the coastal forests of Liberia, Niger Delta, and Cameroon. This unique fauna competes for food, reproductive space and migratory routes with other generalists such as the Loggerhead, green, and leatherback sea turtles). From an ecological perspective, some of these species such as the Trichechus senegalensis, are recognised by Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) as being of outstanding conservation value (IUCN, 2008).

Most coastal lagoons of the region are also of international importance for a significant number of water birds (Kelleher et al., 1995; Diop et al., 2014). The Anambra waxbill, Loango weaver species, and many other waterbirds are restricted to the estuarine and mangrove forests of some countries of this region. The mangroves of the Sierra Leone River Estuary, for instance, are major hosting site for Palaearctic migrant waders, supporting at least eight wintering waterbird species (IUCN, 2007; FAO, 2007; UNEP.,2007; Ngo-Massou et al., 2014). The biological diversity of this entire coastline is complemented by some coastal invertebrate species associated with the mangroves and benthic habitats adjacent to mangroves. This combination of, invertebrates, and fruiting mangrove vegetation attracts larger predators and grazers such as vervet monkeys, marsh mongooses, royal antelopes, and the western Sitatungas, (Tragelaphus spekii), and others. It is estimated that these coastal waters harbour about 239 species of fish, of which over 70% are endemic to the Gulf of Guinea and the Niger Delta (Kelleher et al., 1995; Sankaré, 1999)

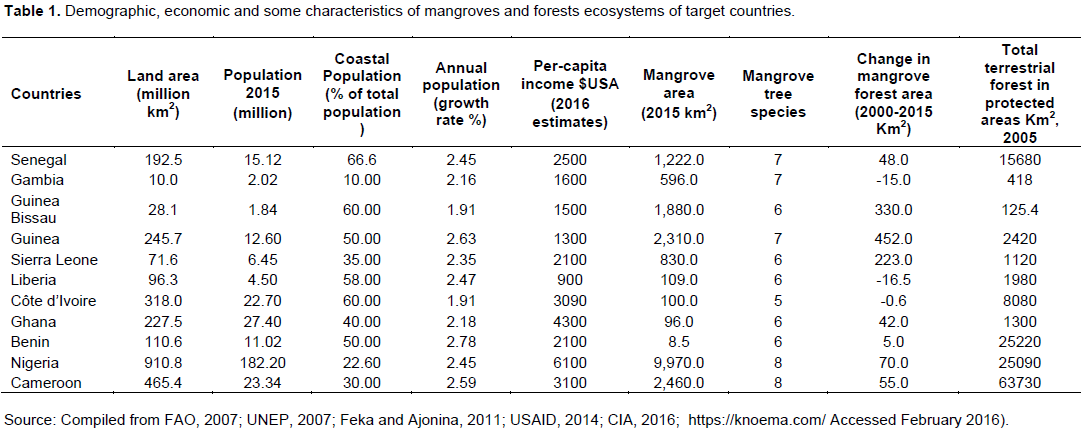

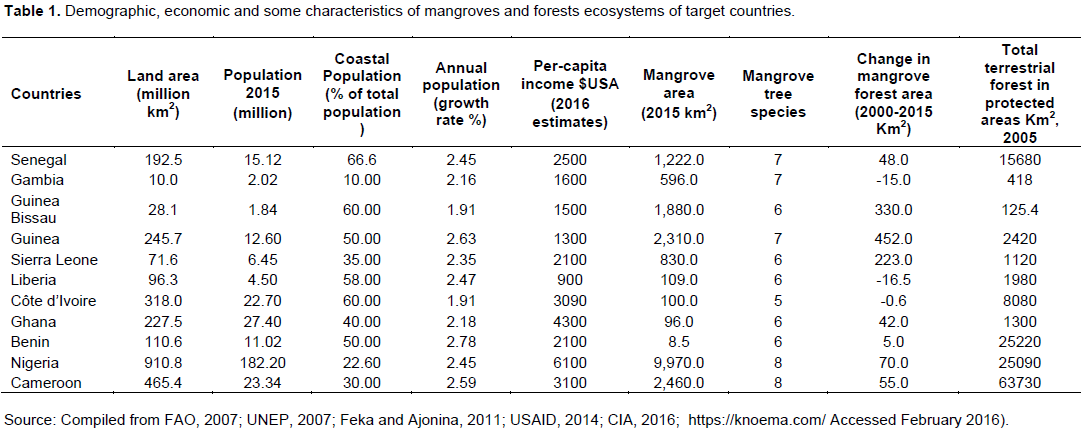

Current data indicates an increasing human population, with, 43.8% of the population across these countries living in or near to coastal ecosystems (Table 1). This coastal growth is heavily driven by socio-economic opportunities in the urban centres of these areas, particularly assets linked to coastal ecosystems. The mean per-capita income across these countries is small (USA$2500±1514.26), compounded by unequal distribution of wealth in countries of the region, which is forcing vulnerable coastal communities to be highly dependent on natural resources for survival and posterity (Feka and Ajonina, 2011). For instance, mangrove forests are a major source of food, timber, fuel-wood and numerous other materials (Kjerfve et al., 1997; Din et al., 2008; Feka and Manzano, 2008; Adite et al., 2013a; Baba et al., 2013). In Benin and Guinea-Bissau, mangroves are a source of medicine to the local people (Da Silva et al., 2005; Teka et al., 2012; Vasconcelos et al., 2015). And although a consistent economic value of mangroves is not yet established for the region, 1 m3 of mangrove fuel-wood costs about $US18/m3 (Feka and Manzano, 2008). These mangrove forests could potentially yield even better economic returns on the carbon markets because of their high carbon stocking densities, estimated at 1048.91 Mg/ha (Tang et al., 2015).

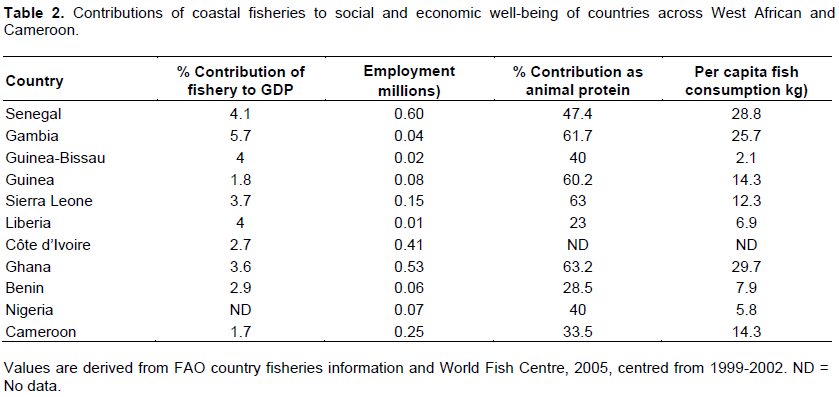

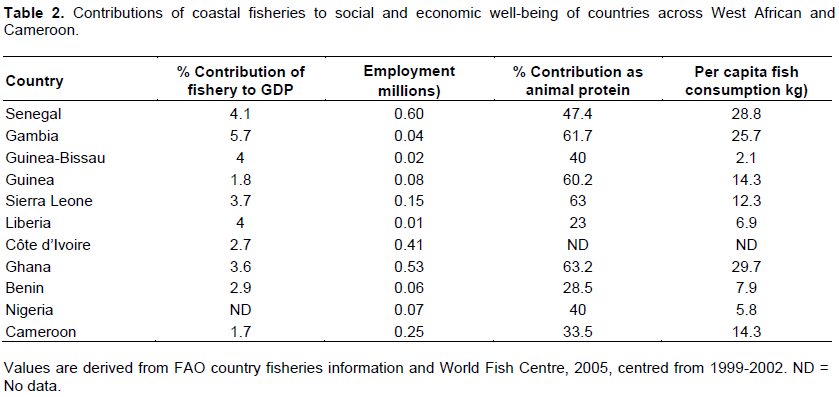

Across countries of West Africa and Cameroon, the scenery of mangroves and beaches adds aesthetic value for tourism and ecotourism to the coastal ecosystems, which is a growing industry across all the countries of study (Feka, 2007; UNEP, 2007; Leijzer et al., 2013). Also, indigenous traditions such as restriction of access to areas reserved for worshiping ancestral spirits and adoration of gods, adds sociocultural and aesthetic value to these coastal habitats (FAO, 2007). Adjacent coastal forests are extensively cleared and used for the cultivation of food crops and cash crops by local people and industries. Cashew nuts, rice, palm, coconut and salt are just some products (Agyen-Sampong, 1999; Daan et al., 2006; Feka and Ajonina, 2011; Green Scenery, 2011; USAID, 2014). Coastal and marine fisheries are vital to the economy of this region, contributing significantly to the social and economic well-being (Table 2). Offshore and coastal extractive industries are rapidly expanding into these countries, and contributing to the national Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of some of these countries (CIA, 2016)

Study methods

The methodology for this study was designed to be iterative and adaptive, to capture inputs from desk review of published articles and progress reports, interviews with field-based project managers and decision-makers, and consultation with coastal ecosystem specialists in countries of West Africa and Cameroon. This study was carried out in two stages, a literature review (stage i) and a field and status project assessment (stage ii),

Stage (i)

The literature review was limited to peer-reviewed articles and technical reports from (1999-2015), but old key foundation documents on mangroves/coastal ecosystem management were included. Published articles were searched online in English in publicly accessible databases. Groups of keywords linked with the and operator were used for the searches. The groups referred to mangrove ecosystem management in the country [e.g. Ghana] or West Africa and Cameroon. For instance, Ecology (keywords such as mangrove forest, species, biodiversity), vulnerability (keywords such as pollution, exposure, impacts…), and conservation (keywords such as reforestation, afforestation, protected area). A total of 65 articles were retained for this study, after removing duplicates and selecting only articles for the indicated period and relevance to the themes of interest. Literature was examined to identify research themes with information/data from research or intervention activities carried out in select countries of West Africa and Cameroon. Themes were not predetermined but were determined

posterior after article review in a simple logistic manner to group information/data availability on a specific theme or objective. Similarly, the team also considered legal, and policy frameworks used to manage mangroves in-country and across the region to gauge progress towards the development of a legal framework for mangrove ecosystem management

Stage (ii)

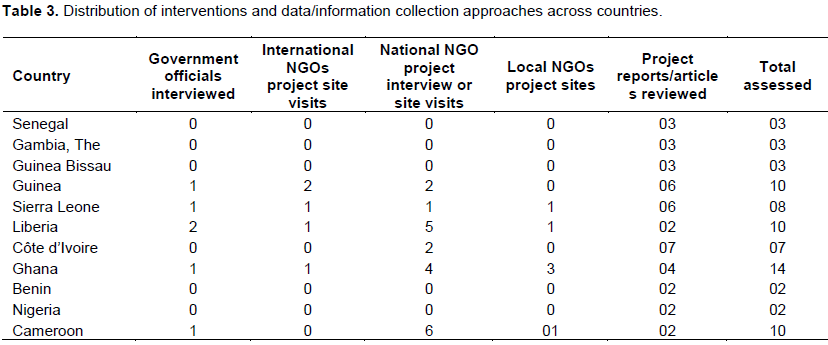

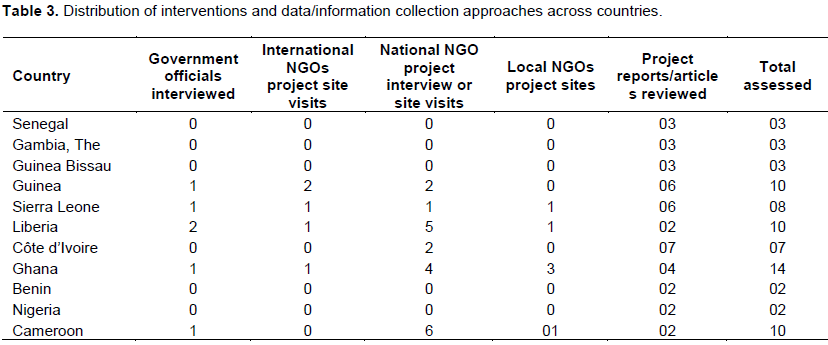

A total of 72 project sites and project reports were assessed for this study to identify how different interventions and actions were developed to conserve mangrove ecosystems. These projects were identified during a separate expert-led literature review (USAID, 2014), and updated in 2015. To be considered, projects were expected to address aspects of mangrove and coastal ecosystem management. Project counts as presented in Table 3 are mutually inclusive. The assessment process was effected through; (a) exploratory semi-structured and informal interviews with relevant project stakeholders, local community members, and local government officials in offices connected to mangrove forests/coastal ecosystem management activities or in the field across countries visited. (b) review of project status reports. Full consideration of those projects and interventions can be found in Table 3. This project report gave insights into how planning for mangrove management is initiated, developed and implemented by institutions across the region, particularly at sub-national level. Information from the interviews and reports was analysed qualitatively into tables, percentages, and bar charts using Microsoft Excel. Assessments were aimed to understand intervention strengths over a twelve-year period (2000-2012), as well as the cursory effects of externalities of these response efforts.

Distribution and characterization interventions

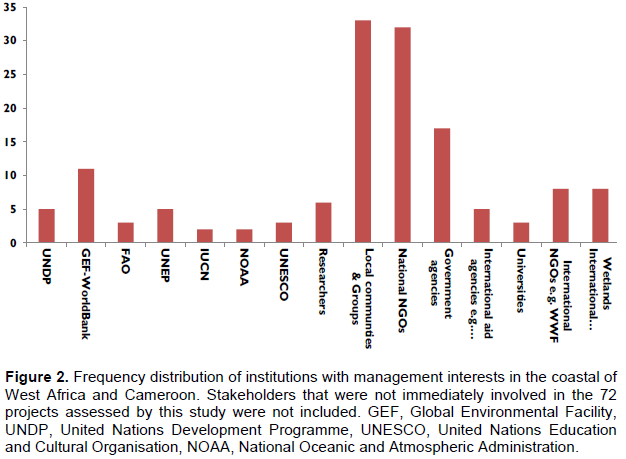

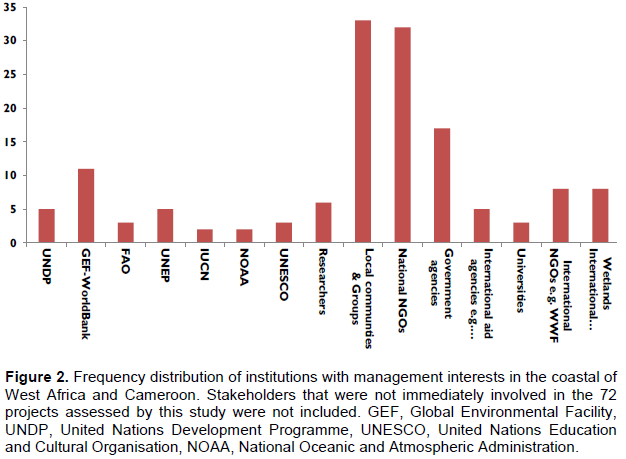

The conservation and restoration of coastal ecosystems across the countries of West Africa and Cameroon are of prime interest to a variety of institutions ranging from governments, multilateral, corporate, international, national, local Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and Community-based organizations (Figure 2). These institutions play various roles, either as funding agencies, intervention implementers, and/or as resource users, to support the sustainability of mangroves in West Africa and Cameroon.

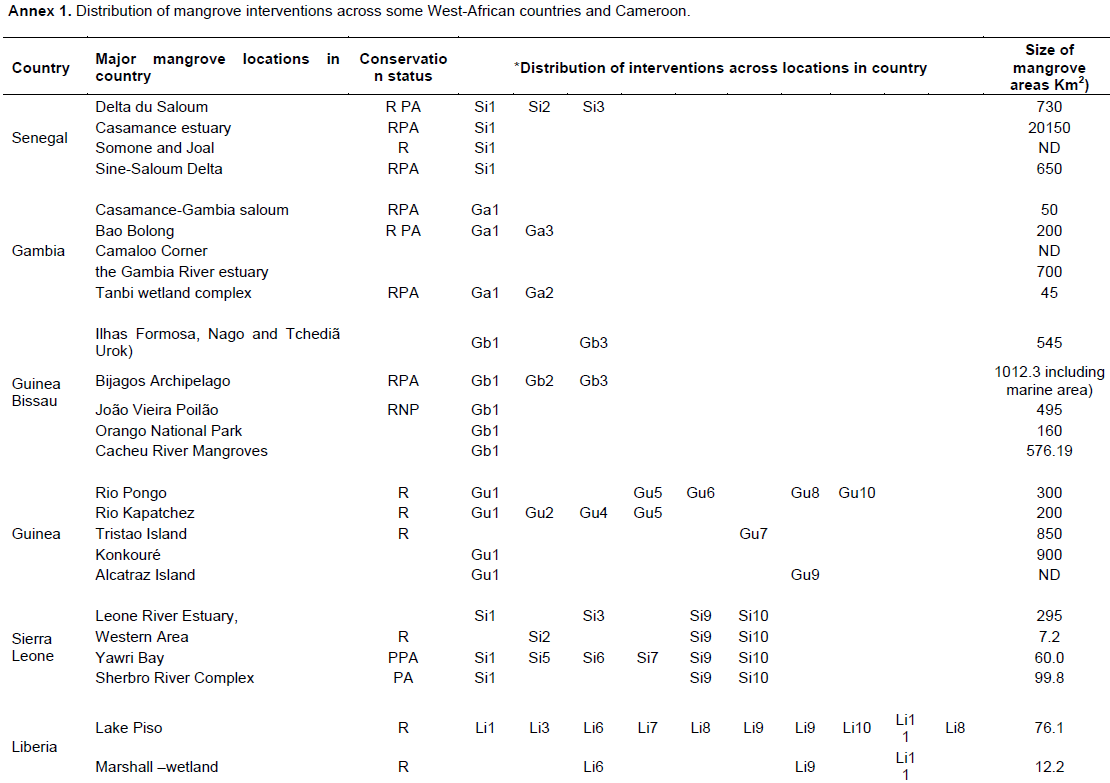

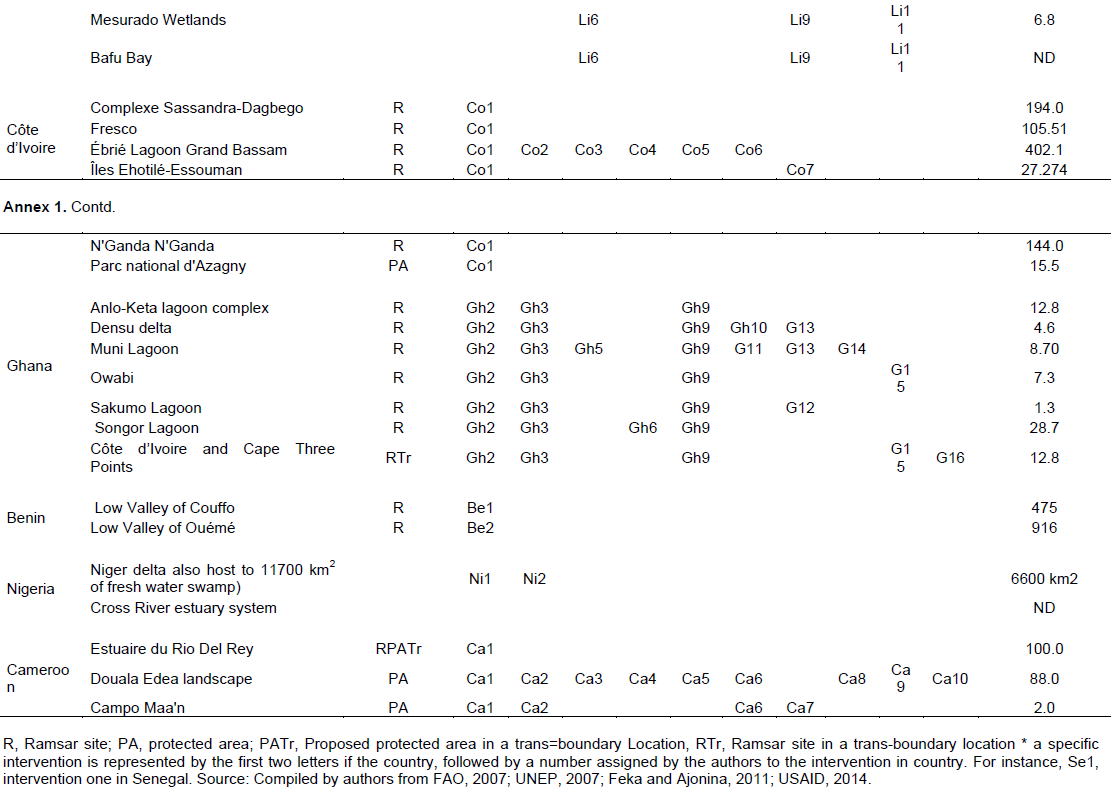

A total of 72 projects were assessed (Annex 1); of which 31(43%) were visited to observe and interview various stakeholders, and 41 (58%) were analysed through the review of articles and project progress reports. These projects were initiated in response to significant environmental problems observed by decision makers or stakeholders’ at easily accessible coastal sites (Annex 1). However, 30% of the projects initiated funding proposals, without proper and prior consultation with local communities or broader stakeholder consultations. Most of the multiyear projects (85%) were undertaken by international aid institutions or multilateral institutions in collaboration with local and regional stakeholders (Figure 2). In these projects, identification of demonstration project sites was guided by national or site-specific biodiversity conservation criteria, like the criteria utilized in this research to select countries of study.

About 60% of the national institutions that facilitated the implementation of projects across countries of West Africa and Cameroon did not include mangroves in their strategic development plan. This suggests that mangroves were not previously a priority conservation focus to these institutions, but were instead added later in the process because of increasing prioritization by international organizations. The international and multilateral institutions that were involved in the implementation of interventions displayed substantial financial power and aimed to implement interventions in a consultative manner, trying as much as possible to engage a broad spectrum of stakeholders. These institutions were most often concerned with high-level stakeholders in government or top national institutions. These international bodies employed more bureaucratic project development approaches, and thus, local community stakeholder awareness of their field-based interventions appeared to be quite small, compared to those implemented by local or national institutions.

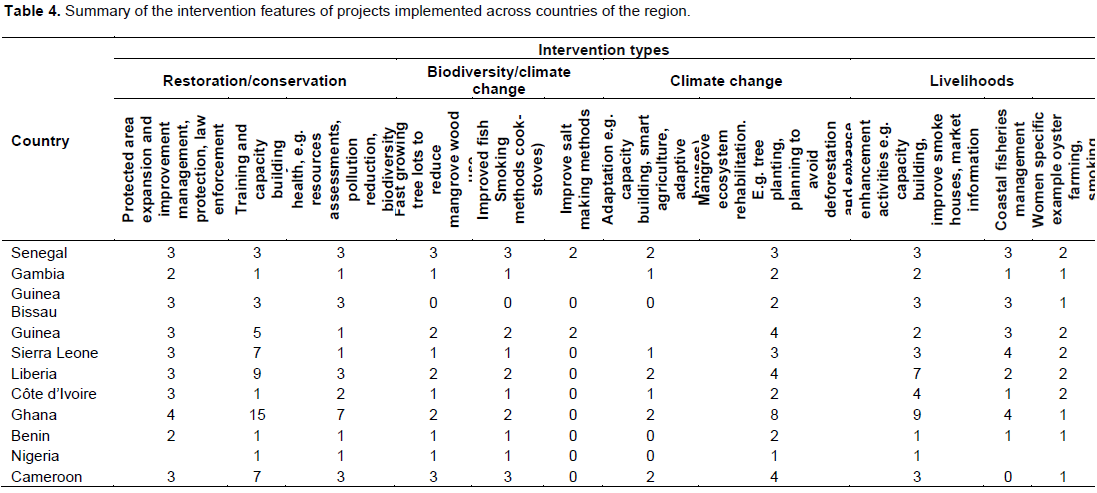

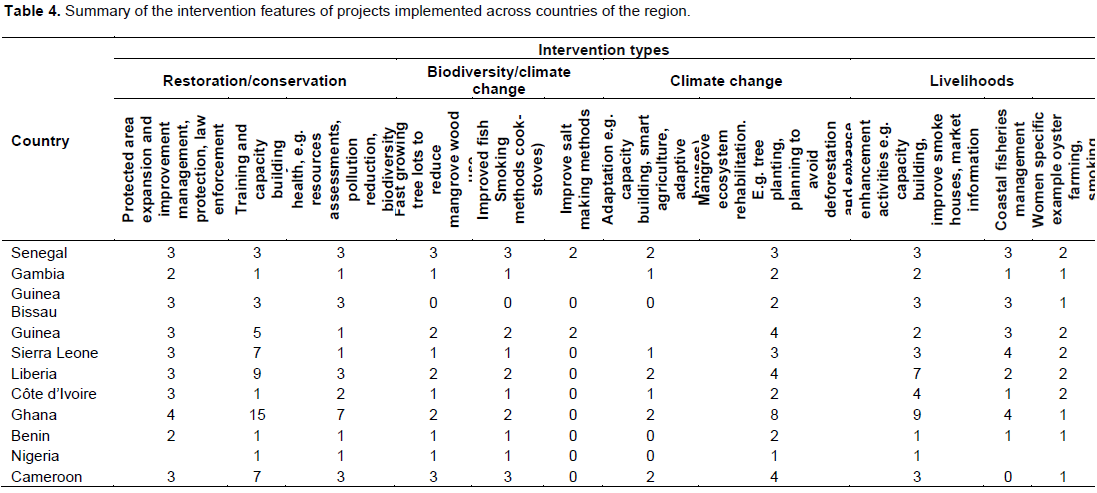

Although all projects seemed to highlight some form of sustainability in their planning language, only 12% of them demonstrated evidence of post-project lifecycles. At the time of field work in 2014, 95% of the projects had been completed or were in their concluding stages, while only 5% were still in active implementation stages. All projects anticipated contributing to specific thematic areas in the following proportions; 100% (72) focused on biodiversity conservation, 14% (10) on climate change mitigation and adaptation, while 49% (35) saw contribution to climate change mitigation as implicit in the projects implemented activities. This grouping is not mutually exclusive. Table 4 is a summary of the features of interventions implemented by projects across countries.

Monitoring and Evaluation (M&E) of project activities was related to the magnitude of funding and length of the project cycle. M&E strategies for short-term projects (lasting one year or less) were limited to short narratives or end of project reports. Projects of longer life cycles (≥1 years) used a variety of M&E3 strategies. The use of mapping and remote sensing tools for monitoring happened in 28% of the projects (mainly projects of interventions by international institutions).

Mangrove ecosystem implementation strategies

Field implementation methods

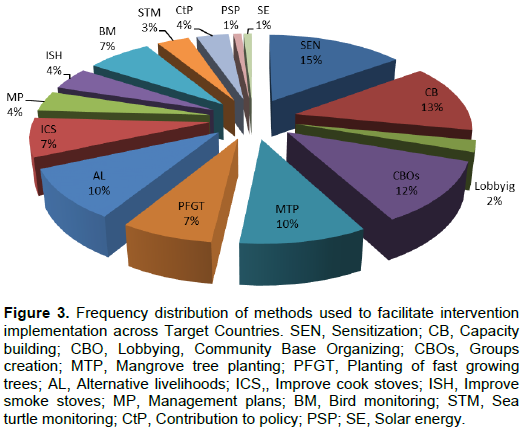

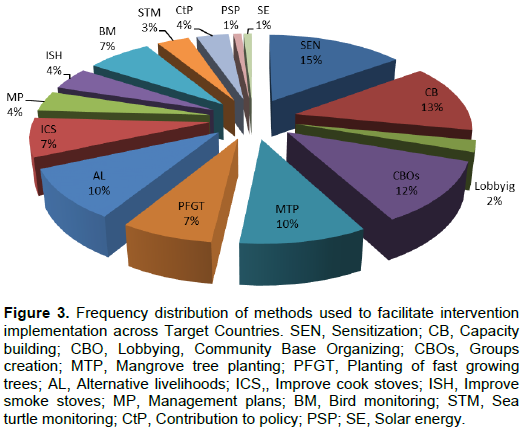

In order to implement various interventions, project staff undertook a range of activities on the ground. The application of these methods varied between projects but not between countries. Using a method or set of method to complete a specific intervention was dependent on the environmental issue at stake, the accessible stakeholders, and the resources available. Figure 3 shows the frequency distribution of implementation methods use in countries. Independent research interventions such as bird or sea turtle monitoring and field surveys were few in numbers, and employed the least number of field implementation methods (1-3), while cross-cutting projects such as “the sustainable mangrove management,” used the largest number of methods. All the mangrove projects assessed during this study employed more than one method to complete a given intervention. For this reason, there was no “typical” mangrove response that is common across all countries. The use of a set of responses for a project was dependent on a variety of programming decisions; including ecosystem features, local community needs, implementer experience, project length, and budget.

Mangrove intervention types

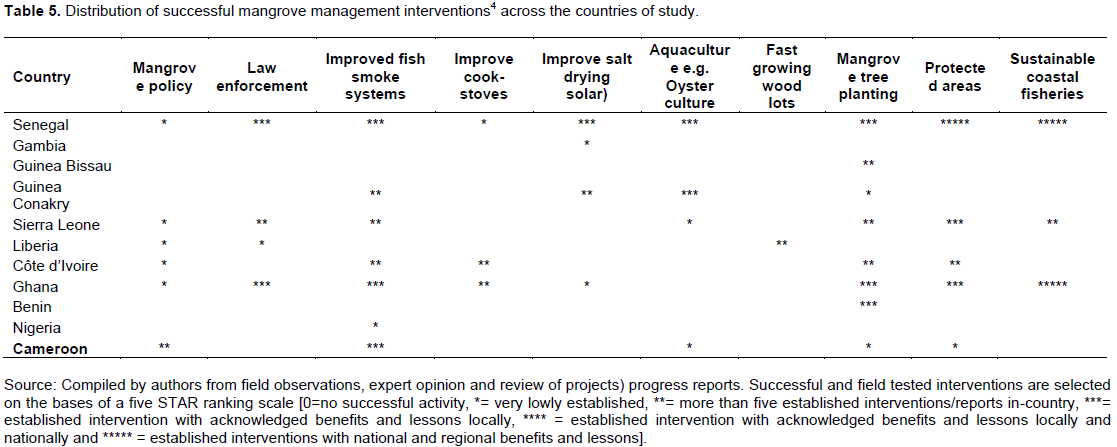

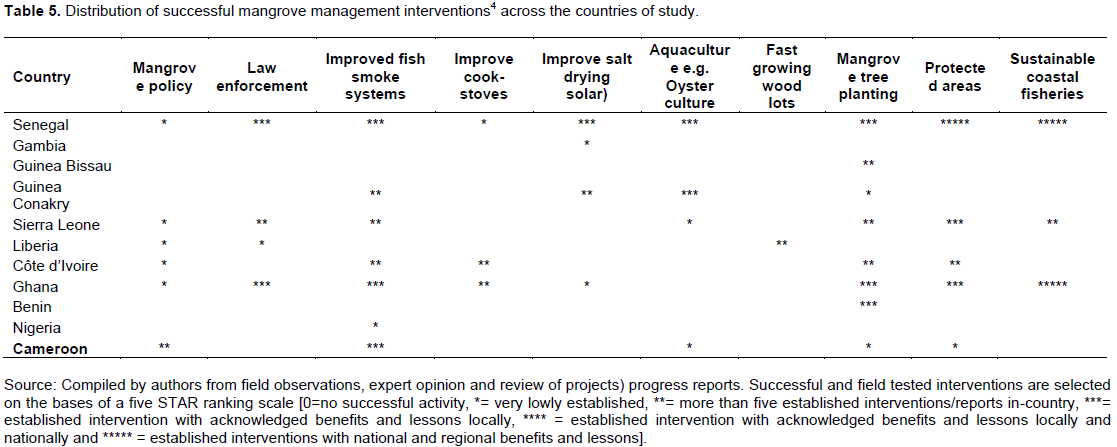

The study found that the conservation of mangroves between 2000 and 2014 in countries of West Africa and Cameroon involved a variety of overlapping interventions. This paper grouped these interventions into two broad complementing categories; (a) biodiversity conservation and sustainable management and (b) ecosystem restoration. Table 5 highlights a short list of field-tested interventions identified from across the countries of study.

Source: Compiled by authors from field observations, expert opinion and review of projects) progress reports. Successful and field tested interventions are selected on the bases of a five STAR ranking scale [0=no successful activity, *= very lowly established, **= more than five established interventions/reports in-country, ***= established intervention with acknowledged benefits and lessons locally, **** = established intervention with acknowledged benefits and lessons locally and nationally and ***** = established interventions with national and regional benefits and lessons].

Biodiversity conservation and sustainable management

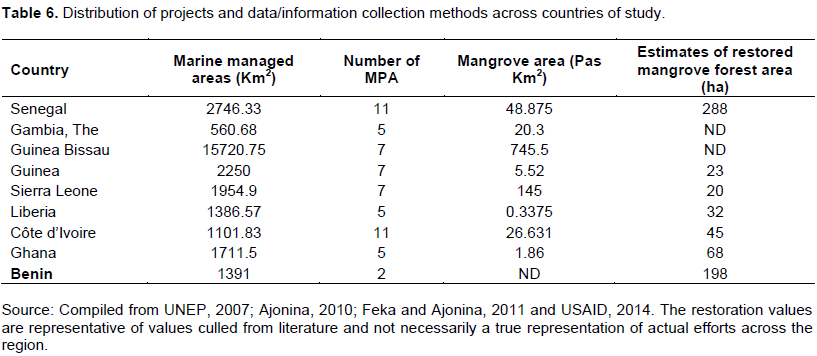

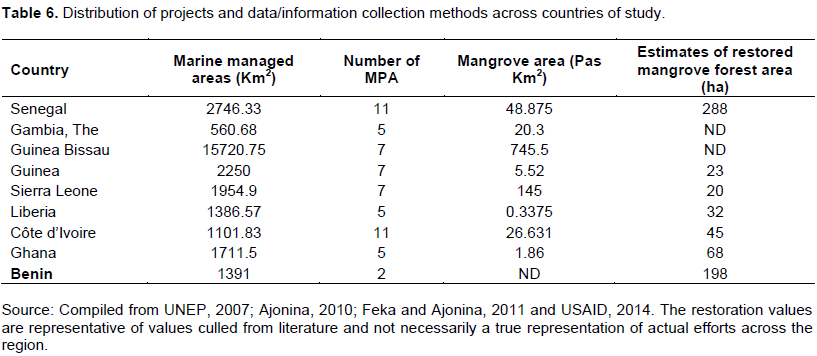

Protected areas: Data from the World Database on Protected Areas (MCI., 2016: Table 6), highlight about 70 Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) across countries of the region, encompassing an area of about 39,500 km2 of marine managed area (~3.80 times less than equivalent protected terrestrial forests area across countries of the region), of which mangroves occupy about 4%. About 10% of these are proposed or have no designation information, 21% are national parks, 50% are recognised internationally (either as world heritage sites and/or Ramsar sites), and 30% are IUCN classified. Most of the projects assessed in this study supported MPA sustainability by promoting the reduction of pressure on mangrove resources through various activities (Table 4). Regardless of status, less than 40% are under some form of management or are in the process of developing a management plan. As a result of poor management and pressure from anthropogenic activities, some of these MPAs are in advanced states of degradation, as in the MPAs in Nigeria (e.g. Apoi Creek Forests Reserve, Stubbs Creek Forest Reserve), Guinea (Konkouré Ramsar site) and Benin (Nazoumé MPA). Most of the successfully established MPAs in this region are in Senegal (e.g. Delta du Saloum UNESCO-MAB Biosphere Reserve), Guinea-Bissau (e.g. Bijagós UNESCO-MAB Biosphere Reserve), Sierra Leone (Sherbro Bonthe River Estuary) and the Gambia (Tanbi Wetlands Complex Ramsar Site).

Evidence from this study indicates that the approach to protected area management is moving from a centralized government-led model (with little community involvement) to other forms that have a greater focus on sustainable development goals and governance orientations, such as stakeholder participation and benefit-sharing equity (Cormier-Salem, 2014). This transformation is a result of changing environmental conditions and responses to global environmental agreements and conservation conventions such as the Convention on Biodiversity (CBD, 2009). Because of increasing commitments to these agreements, the number of MPAs and the management objectives of these tools have been changing, across countries and Cameroon (Renard and Touré, 2012; Cormier-Salem, 2014).

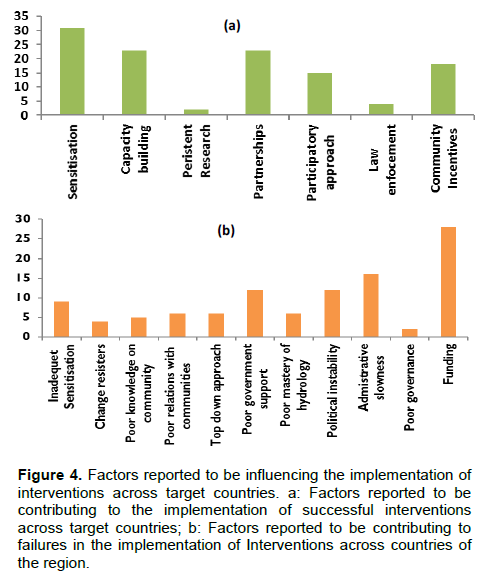

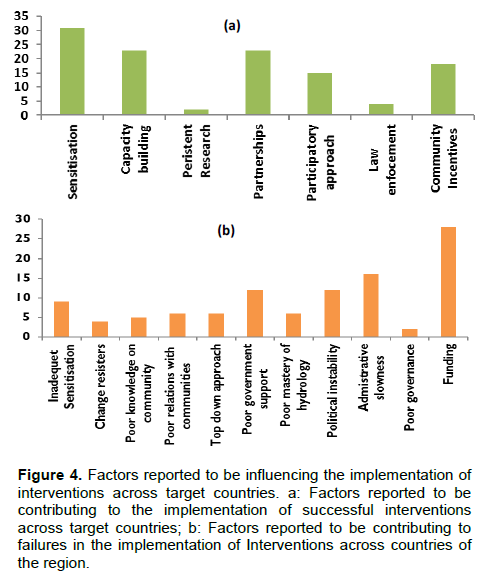

Community-based Mangrove conservation initiatives: About 90% of all projects assessed aimed or used some level or form of Community-based management (CBM) to manage mangroves. Mangrove CBM initiatives were successfully implemented in Benin, Ghana, and Liberia (USAID, 2014). The factors that contributed to shaping the success of CBM initiatives are summarised in Figure 4a. Because of these achievements, some mangrove areas have been rehabilitated across countries of West Africa and Cameroon (Table 6). Co-management of MPAs is also gaining popularity across some of the countries of study, as in the case of Sierra Leone, where co-management of the Sherbro River MPA has resulted in increased protection of mangroves and increases in fish catch. This has, in turn, stabilised families by reducing the need for male fisher’s mobility between villages and between countries (EJF, 2013).

The co-management of MPAs, including mangroves, have contributed to livelihood improvements by introducing community enterprise initiatives such as tomato farming around Songor in Ghana, community micro-lending and fishing schemes in Cayar, Senegal and oyster cultivation and commercialisation in the Greater Banjul area of the Gambia. These initiatives have helped to sustain incomes and motivate communities to engage effectively in the management of mangroves and coastal ecosystems conservation (Diop et al., 2006; Sall et al., 2012). However, CBM mangrove initiatives across countries such as Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea and other countries of the region have not always been successful due to reasons highlighted in Figure 4b.

Ecosystem rehabilitation

Mangrove ecosystem rehabilitation: Restoration is commonly described as an act or process of returning something to its original condition or position (English Cambridge dictionary, 2016). Although, degraded ecosystem can never be returned to its original condition, rehabilitation of degraded ecosystems is a much more manageable task, as it involves returning degraded mangroves to a healthier condition, with ecosystem structure and characteristics that are partially or fully functional. Successful mangrove planting is happening in some countries of the region (Table 6), and community management plans and planting of fast-growing non-mangrove trees for alternative timber sources are conventional approaches to reducing pressure on mangrove ecosystems, thereby allowing overharvested areas to regenerate naturally. A series of factors were identified as promoting the success or failure of these initiatives (Figure 4a and b). About 35 of the projects assessed attempted rehabilitation interventions. Most of these initiatives, however, conflated rehabilitation with mangrove tree planting. Reports indicated that restoration planning deficiencies included lack of prior feasibility studies, lack of post-planting monitoring, and poor community participation in many of the mangrove rehabilitation interventions in most of the countries except for Benin, Ghana, and Senegal.

Enhancement of livelihoods: Several interventions were implemented with the aim of reducing anthropogenic pressures and dependencies on mangroves and other coastal ecosystem resources. This was done by either providing additional or enhanced income streams to community members that are reliant on this ecosystem for subsistence. About 82% of the 72 projects used livelihood enhancement activities as a way to reduce pressure on the ecosystems. Some of these livelihood activities are highlighted in Table 4. The primary types of livelihood activities observed about mangrove preservation activity are improved (more active) fish smoking, improved salt drying technologies, and alternate modes of income generation. Alternative ways of revenue generation were particularly diverse from site to site, with various forms of animal husbandry being common snails, cane rats, and oysters).

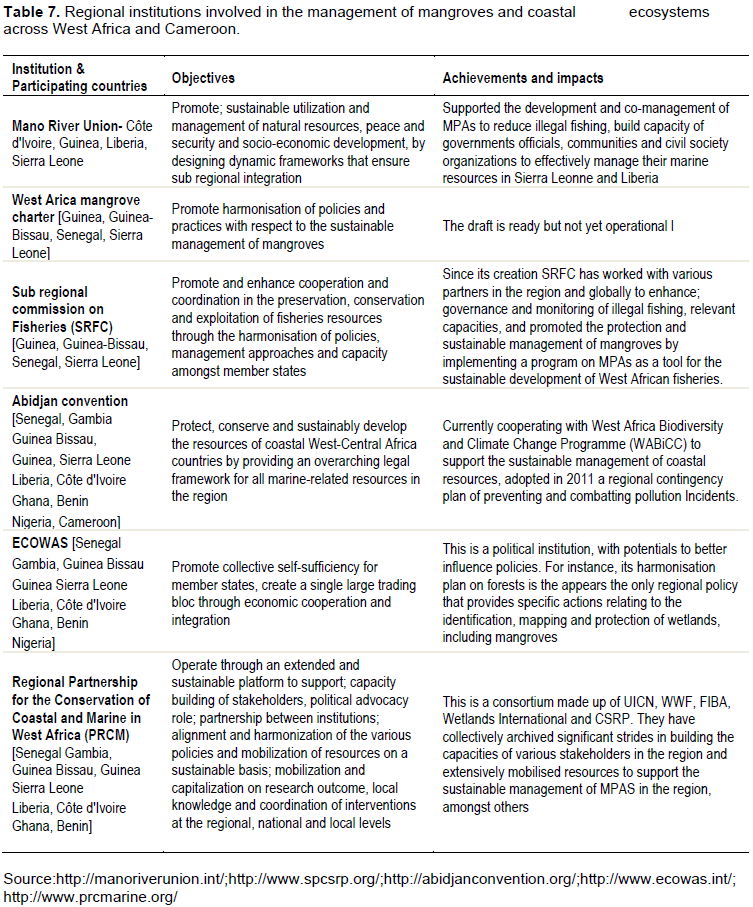

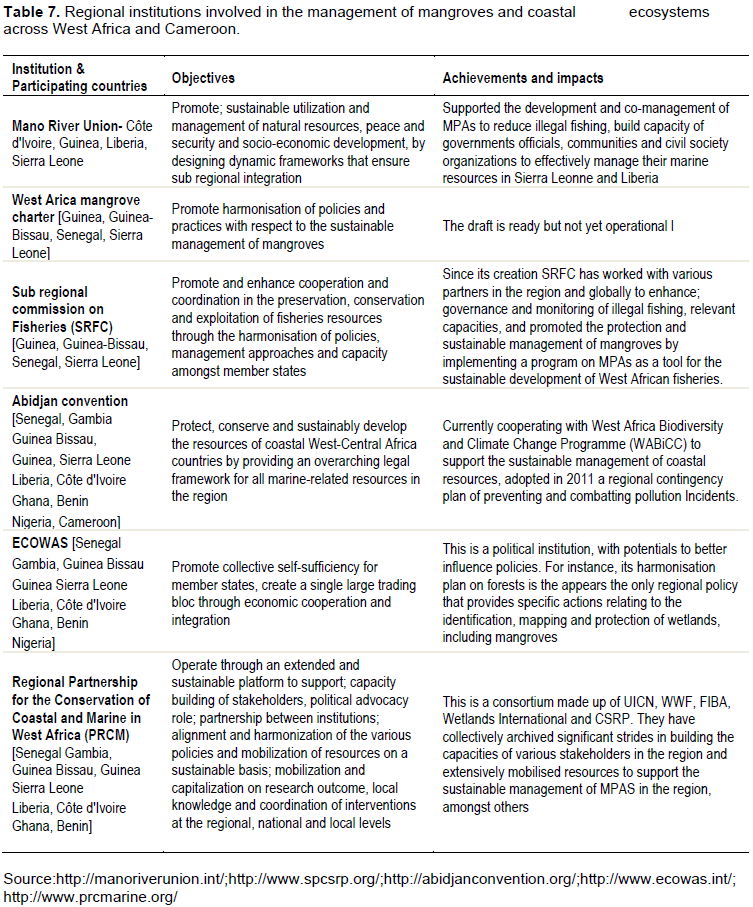

Legislative and policy reform: Countries across the region have ratified a series of international agreements that promote biodiversity conservation, including mangrove-specific subsets (CIA, 2016- World-Fact Book country profiles). Agreements such as the Abidjan Convention, Marine Dumping, and Marine Life Conservation refer to the sustainability of marine life, while others, such as …. only implicitly reference marine life and mangroves. The Treaty on Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Environmental Policy and the draft Charter and Action Plan on Sustainable Mangrove Management refer to mangroves. These international and regional instruments aspire to promote the harmonization of policies that promote the sustainable management of coastal resources by setting national and regional guidelines that improve coastal and marine resources governance; including mangroves and fisheries

Many regional institutions and initiatives have been established to facilitate the implementation of these agreements. However, these initiatives do not often engage all countries from the region to participate in the development of resources management guidelines (Table 7). Hence, there is, therefore, need to extend and consolidate the existing regional mangrove draft charter and working groups to all countries of the region. A next logical step will be the domestication of the established regional policies at a national level in a way that will facilitate the development of legislations for mangrove protection, sustainable development, and climate change mitigation and adaptation. Considering the migratory nature of coastal dependent biodiversity (fauna), each country should integrate elements of regional policy frameworks into their national legislations in participation with the regional institutions. One of the strongest challenges for international treaties/regional intuitions in countries of West Africa and Cameroon is that countries adopt them, create focal points and then do not give them the required resources to implement. At the national level, countries such as The Gambia and Cameroon have developed draft policies and legislations for mangrove management (Government of Cameroon, 2010; Government of Gambia, 2015). While in Benin, Ghana, Liberia and Sierra Leone, the management of mangroves is encapsulated within wider Wetland policies.

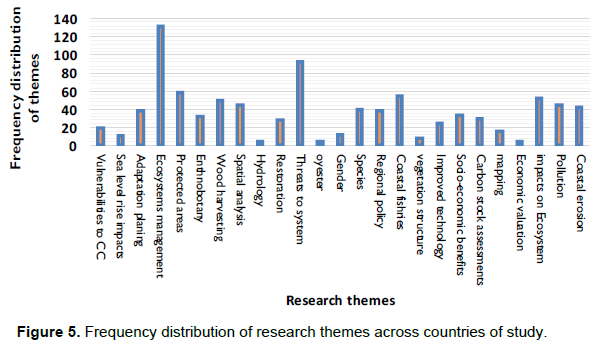

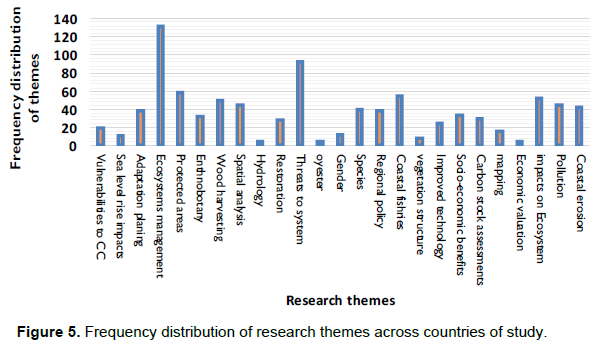

Capacity building and research: Capacity building activities included the use of public radio announcements, flyers, demonstrations, and workshops promoting changed behaviour and lobbying for policy change. Since the 2000’s, research has generated a considerable volume of literature with data that can be used to support the sustainable development of mangroves and other coastal ecosystems in West Africa and Cameroon. Documents, including technical reports and peer-reviewed journal publications, were analysed. Of all these materials, over 24% were technical reports and 76% peer reviewed articles. These articles covered twenty-six thematic/research objectives. About 65% of the articles covered cross-cutting themes. Figure 5 shows the frequency distribution of research topics across studied countries of the region. This information gives a birds-view of the investigation effort and data that could influence behaviour and raise awareness amongst policy makers and promote rational decision making, but it is by no means exhaustive.

Current state of mangrove forests

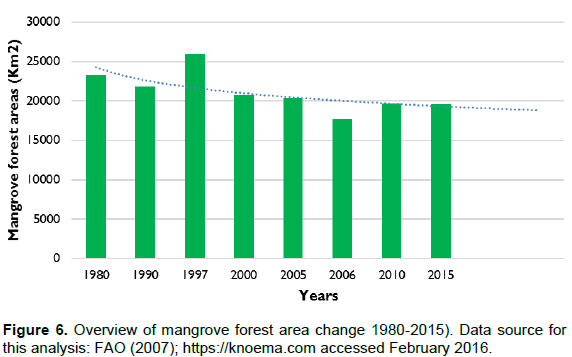

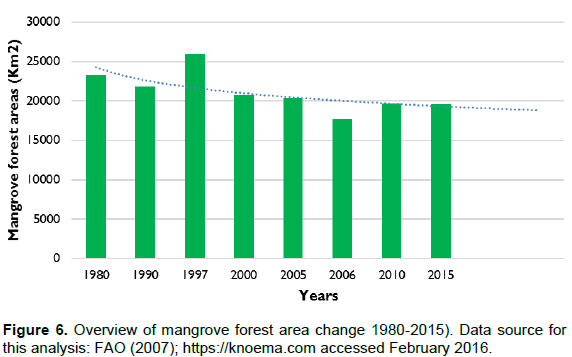

An analysis of field interviews, literature and reporting data on the state of mangrove forests across countries of West Africa and Cameroon was carried out, to serve as a rough proxy measure of conservation efforts between 2000 and 2014. Results revealed that between 2000 and 2015, about 6% of mangrove forests disappeared (Citation). This value represents an annual depletion of about 79.53 km2 of mangrove forests, with a mean annual loss of 7.23±10.45 km2, per country. This rate is 1.59 times lower that the 126.28 km2 of equivalent loss per year for the previous period (1980-2000), across the same countries this suggests that the loss in mangrove forest may be slowing down, though the gradient remains negative (Figure 6). Côte d’Ivoire, The Gambia, and Liberia appear to have cumulatively gained in mangrove forest area (Table 6). This slowdown in trend implies that cumulative actions undertaken to sustain mangroves and coastal ecosystems across the region may be curbing the rate of mangrove ecosystem loss. However, despite their conservation efforts; Guinea and Sierra Leone appear to be losing significant amounts of mangrove forests (Table6).Now, however, it is not certain if this changing trend is the result of a lack of conservation efforts or data insufficiencies.

Intuitional capacity, Interventions, and Outcomes

With respects to project development and implementation, most of the international institutions had a more structured approach, while most of the national organizations had a rather casual approach. This tendency is however not uncommon in developing countries (Adger et al., 2003; Feka, 2015). Moreover, most of the national implementing institutions exhibited typical governance weaknesses related to staffing and logistic insufficiencies. This finding is a common phenomenon with other developing country institutions such as Kenya (Adger et al., 2003; Gordon et al., 2009). Irrespective of institutional classification, methods (Figure 3) used to implement interventions (Table 5) were like those used by institutions in East Africa and South-East Asia (FAO, 1985; FAO, 2001; Leijzer and Denman, 2013). However, most of these interventions employed various levels of fragmented responses to address threats identified across sites (Tables 4 and 5). Overall, an integrated approach that considers mangrove forest heath as influenced by a wider land/coast/seascape processes would yield better results (Fabbri, 1998; Feka and Ajonina, 2011)

Lack of M&E in many small projects made it difficult to verify outputs and outcomes of field interventions undertaken by some of the national and local intuitions. The international intuitions employed various M&E techniques, but even those were more focused on project managing and building partnerships rather than assessing and measuring field-based conservation outcomes. Moreover, the limited use of satellite- mapping and remote sensing tools for M&E might be linked to the technological challenges common in most of the countries of West Africa and Cameroon (Akegbejo-Samsons, 2009; Salami et al., 2009; Carreiras et al., 2012; World Bank, 2015), exacerbated by a general lack of knowledge on alternative low-cost open source satellite-based mapping technologies. The limited use of these tools indicated that most projects did little spatial planning and subsequent reporting of project outcomes. Regardless of the challenges, mapping and remote sensing has been extensively used to gain insights into spatial and temporal distribution of mangrove ecosystems, species, state of mangroves, biomass, carbon stocks, and vulnerabilities globally (Kovacs et al., 2001, Fromard et al., 2004; Dahdouh-Guebas et al., 2005; Giri et al., 2014; Tang et al., 2014; Dan et al., 2015).

It is essential for prospective mangrove conservation programs to prioritise mapping and remote sensing units into programs to facilitate the monitoring of project outcomes. Such units will significantly improve our understanding of real-time interventions and threats to mangrove ecosystems. Also, there is a general need to empower national and local institutions on the sustainable management of mangroves and coastal ecosystems in the region; taking into consideration current challenges plaguing coastal ecosystems in the region. This capacity development drive must be context specific, after a clear institutional gap analysis. Also, in the future, it is imperative that international institutions engage more with a wider range of community institutions and representatives from project inception. This process should include ensuring knowledge and technology transfer through identification and training of local and government institutions for monitoring and post-project impact evaluation.

Factors driving the successful delivery of mangrove conservation interventions by institutions across countries

This study highlights the deliverables (Table 4 and 5) of 72 interventions5 undertaken from 2000 to 2014 to sustain mangroves across countries of the region. A variety of factors altered the implementation of these interventions (Figures 4a and b). However, the outcome of each of these interventions was the result of a combination of many field methods, mostly influenced by the governance capacity of the implementing institution. Across the countries of West Africa and Cameroon, there is a growing wealth of information/data (Figure 5) from various stakeholders, but research effort is unevenly distributed across studies countries. This study identified that research from across countries of West Africa and Cameroon was used in support of restoration programs and the development of improved fish-smoking and solar technologies for salt making. This suggests that adequate research could contribute to the identification and support of other sustainable management strategies for mangroves and coastal ecosystems. These results are consistent with the findings of CEC (1992), Diop et al. (2006) and Diop et al. (2014). Overall, most of the articles reviewed by this study appear to be managerial and superficial in nature. Moreover, this literature review and research effort identified a gap in knowledge and lack of information/ data on the ecology of mangrove species, regeneration of species, remote sensing and distribution of species, ecological processes, economic valuation of mangroves and the implications of climate change on species and human well-being across countries of the region remains limited and scarce.

This lack of information makes it difficult to support informed decision-making for coastal ecosystems management in countries of West Africa and Cameroon. It is, therefore, essential for funding institutions to be more flexible with project implementation strategies by enabling implementers to proactively collect data and monitor ecosystem change in the interests of identifying and effecting adaptive changes when they occur during a project’s life, rather than being dogmatic (BSP, 1993). This approach offers better opportunities to identify how interventions are making progress towards goals and what ecosystem changes are occurring if any. Hence, there is a need for continuous research across all countries of the region to holistically understand the socio-economic and ecological values of mangroves and coastal ecosystems. Research within mangroves and coastal ecosystems in East Africa and South East Asia have led to the development of strategic management plans that have attracted sustainable funding for development and conservation initiatives (Spalding et al., 2010; Fischborn and Herr, 2015). Adopting similar approaches in the West African and Cameroonian coastal ecosystems would be equally beneficial.

This study identified that sensitization activities were also central in the implementation of field activities across all countries of West Africa and Cameroon (Figure 4a). Similar approaches (e.g. use of workshops, leaflets, and radio messages), have been used to change patterns of human activity and behaviour towards mangroves and coastal ecosystem in other developing countries (FAO, 1994; FAO, 2001; World Bank et al., 2004). As reported by interviewees during this study, sensitisation was an essential tool for capacity building that caused local people around the Ebiere Lagoon in Cote D’Ivoire to understand that planting of fast growing trees was a feasible alternative for mangrove wood as a source of affordable energy. Moreover, active engagement of stakeholders through the participatory approach was reported as a facilitating strategy for success across some interventions in target countries of the region. This approach led to the successful co-management of MPAs in Sierra Leone and community restored mangrove areas in Benin and Ghana. The importance of the participatory approach in intervention facilitation lies in its ability to support the development of transparency, fairness and partnership creation among local institutions (FAO, 1994). These virtues were observed in all the successful interventions assessed by this study. Most of the implementers that employed this approach credited it with building stakeholder interest in participation in the conservation process while creating opportunities to generate additional funding and hence project sustainability.

Similarly, the use of participatory approaches in mangrove initiatives have contributed to policy reforms, biodiversity conservation and livelihood improvement among local communities in Kenya, Indonesia the Philippines (FAO, 1985; Kairo et al., 2001; McShane and Wells, 2004; Fischborn and Herr, 2015).

The execution of feasibility studies to understand the root causes of mangrove ecosystem degradation was limited to some interventions in Benin, Ghana, and Senegal. These countries have delivered successful restoration programs (FAO, 2007; Ndour et al., 2009; Sall et al., 2012). The study identified some restoration planning deficiencies, which have previously been reported in countries of this region and other places around the world (World Bank et al., 2004; Primavera and Esteban, 2008; Egnankou, 2009; Ajonina, 2010; Lewis and Brown, 2014). Most of the implementing institutions conflated mangrove restoration to tree planting. However, mangrove rehabilitation should be principally understood as a process of reducing the primary stressors, which collectively act on mangroves, to create improved environmental conditions for plant regeneration and growth. These stressors, and how they influence mangrove regeneration and growth have been extensively studied (Kairo et al., 2001; World Bank et al., 2004; FAO, 2007; Diop et al., 2014; Lewis and Brown, 2014). However, this study identified that this information is scarce in countries of West Africa and Cameroon. Regardless, of the constraints, the decision to rehabilitate a given mangrove area should grow from the recognition that the ecological characteristics and functions of that particular ecosystem cannot continuously auto-sustain (World Bank et al., 2004). In this event, rehabilitation should be a process that is not necessarily synonymous with tree planning but encompasses a series of basic steps and technical procedures that will ultimately inform what field actions are necessary and possible (Lewis and Brown, 2014). It is only when indispensable that restoration may be facilitated by human planting and natural regeneration support using approaches that reduce the anthropogenic impact as a by-product of other preservation activities such as establishment and enforcement of protected areas.

Reliance on the current extent of MPA coverage (Table 6) as an indicator for the protection of mangroves is no guarantee for this ecosystem’s sustainability. The number of MPAs might not be a valid indicator because the creation, enforcement, and management of MPAs in West Africa and Cameroon are heavily constrained by financial and governance challenges (Akegbejo-Samsons, 2009; Renard and Touré, 2012). Furthermore, efforts to create and improve management of MPAs are also being undermined by climate change. Janes et al. (2015) point out that most of the birds, amphibians, and mammal species found in the MPAs outlined in Table 6 are vulnerable to the effects climate change. These challenges are also being compounded by high dependence levels on mangroves and coastal ecosystem resources by various stakeholders, as a result of low living standards (Tables 1 and 2).

Some of the regional partnerships highlighted in Table 7 are promoting the development of coastal ecosystems by triggering the required political support and financial resources for the sustainable management of MPAs in countries of the region. However, these partnerships are limited to a few West African countries. MPAs have a proven track record for biodiversity conservation, as well as acting as safe grounds for regeneration, gene banks, research, and tourism (FAO, 2001; McCclanahan et al., 2005; Salami et al., 2010). It is essential for all countries of West Africa and Cameroon to commit and improve political and financial support for the sustainable development of MPAs in the region.

Institutional and externalities that antagonise mangrove and coastal ecosystems conservation across countries

This study has shown that many factors cumulatively contribute to the successful management of mangroves in countries of West Africa and Cameroon. However, internal institutional deficiencies and external drivers may influence efforts directed towards the conservation of mangrove ecosystems in these countries. This study identified and broadly categorized these factors into four groups.

Institutional insufficiencies: Some of the institutional inadequacies have been discussed (Figure 4a). Additionally, some of the regional institutions (Table 7) are only active nationally or in a limited number of countries, although they may have a regional mandate to sustain mangroves. Within these countries, there are too many administrative intuitions with overlapping or devolved roles, and no clear collaborative platform between institutions (Macintosh and Ashton, 2002; Gordon et al., 2009; Lawson et al., 2012). These issues are common in many developing countries (FAO, 1994; World Bank, 2015), but are especially prevalent in Cameroon, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea and Nigeria. It is important to address these failures because doing so will create conditions that are likely to attract suitable investment/interest for a sustained conservation and management of coastal ecosystems across the region.

Political marginalization of mangroves: The establishment of adequate support policies and appropriate legislation is an essential step in the management of natural resources (World Bank et al., 2004). As observed by this study, government staff contributed to the management of mangrove and stocks in countries such as Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Ghana by supporting the implementing institutions’ right to enforce natural resource laws. This enforcement was strengthened at the community level by sensitised groups in Ghana and Sierra Leone, who actively reported illegal activities such illegal mangrove wood harvesting, poaching of sea turtles and the presence of illegal fishing fleets close to community fishing areas. Regardless of these collective efforts, there are no legally established policies for the management of mangroves across all countries of the region (Feka, 2015). This lack of specific legislation on mangroves and its embodiment, within more general natural resource management frameworks, institutionalizes jurisdictional ambiguities and hence undermines the strong protection of mangroves by legal means (Walters et al., 2008; Van Lavieren et al., 2012). Countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, and Mozambique have developed sound policies guiding the management of mangroves in in their specific countries (Macintosh and Ashton, 2002; World Bank et al., 2004). Countries such as Malaysia, Thailand, Philippines and Pakistan have for a long time guided the management of mangroves using specific legal policies (FAO, 1985; FAO, 1994; Spalding et al., 2010). These policies were initially promoted to develop economic industries such as the production of; poles, pulp, logs, chips, charcoal fuel-wood and conversion for aquaculture (Choudbury, 2002). However, the frameworks of these initial policies improved over time to include social components (for example community participation, poverty reduction), and environmental components like mangrove conservation, protection, and restoration (World Bank et al., 2004). This suggests that (recognizing deficiencies from previous policies), those initial frameworks did guide developments towards the contemporary legal management of mangroves in these countries particularly when coupled with emerging challenges such as climate change and the importance of mangroves to food insecurity.

This lack of legal frameworks for the management of mangroves in countries of West Africa and Cameroon is a clear indication that while political perceptions on the value of mangroves might be changing elsewhere (Spalding et al., 2010; Van Lavieren et al., 2012), governments across this region have not yet realised the true value of these ecosystems.This continuous marginalisation of mangroves is rooted in the inability of governments in the region to perceive direct economic benefits from mangrove ecosystems (Feka and Ajonina, 2011) coupled with the relatively small size of mangrove forests, which are about thirty-nine times smaller than terrestrial forests (Table 1), in the area. Global financial institutions such as the World Bank and the African Development Bank were central to the emergence of legislative and policy frameworks for terrestrial forest management in these countries during the early 90’s. With the increasing importance of mangroves and other coastal ecosystems for food security, poverty alleviation and the management of climate risks (Dahdouh-Guebas et al., 2005a; UNEP, 2007; Lawson et al., 2012; Adite, 2013), it is vital that these financial institutions intervene to promote policy reforms for mangrove management across these countries. These reforms to the sustainable management of mangroves and coastal ecosystems are particularly urgent because coastal areas are hosts to major industries and infrastructure such as seaports that generate over $150 billion in trade annually across this region (UMOUA and IUCN, 2010). This slow pace of policy reform is accentuating the depletion of coastal ecosystems because mangroves are continuously being treated as “open access” resources (UNEP, 1999; IUCN, 2007; Feka and Ajonina, 2011; Diop et al., 2014). Moreover, this lack of legislation makes it extremely difficult for a conservationists to conserve and protect mangroves and gives developers an incentive to generate economic justifications to convert mangroves and coastal ecosystems for business purposes, rather than for conservation (FAO, 1994).

Unsustainable socio-economic trends and population growth: The aesthetic scenery of coastal ecosystems is exploited for tourism, a sector that generates substantial revenue to countries such as Senegal, the Gambia, and Ghana among others (Leijzer et al., 2013). Other development initiatives spanning across this coastal edge include; ports6, dams and petroleum exploitation developments established to support the socio-economic prosperity in some countries of the region such as Cameroon, Ghana, Liberia and Nigeria (Kjerfve et al., 1997; UMOUA and IUCN, 2010; USAID, 2014). These developments are attracting various stakeholders, which seek to benefit from employment opportunities offered by these industries. Thus, the coastal population of this region is increasing (Table 2), but this trend is not limited to this coastal region, as more and more people are moving closer to coastal zones globally (MEA, 2005).

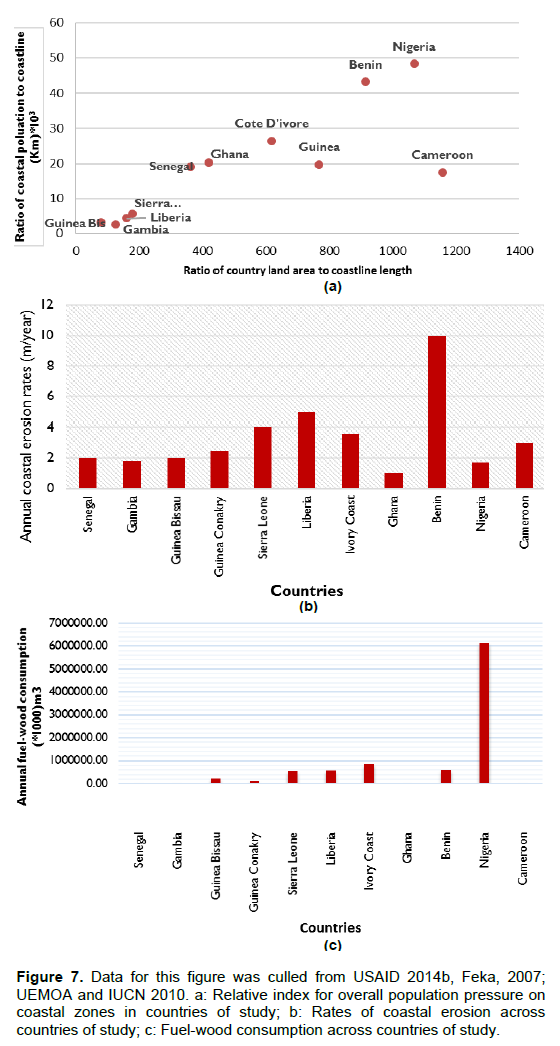

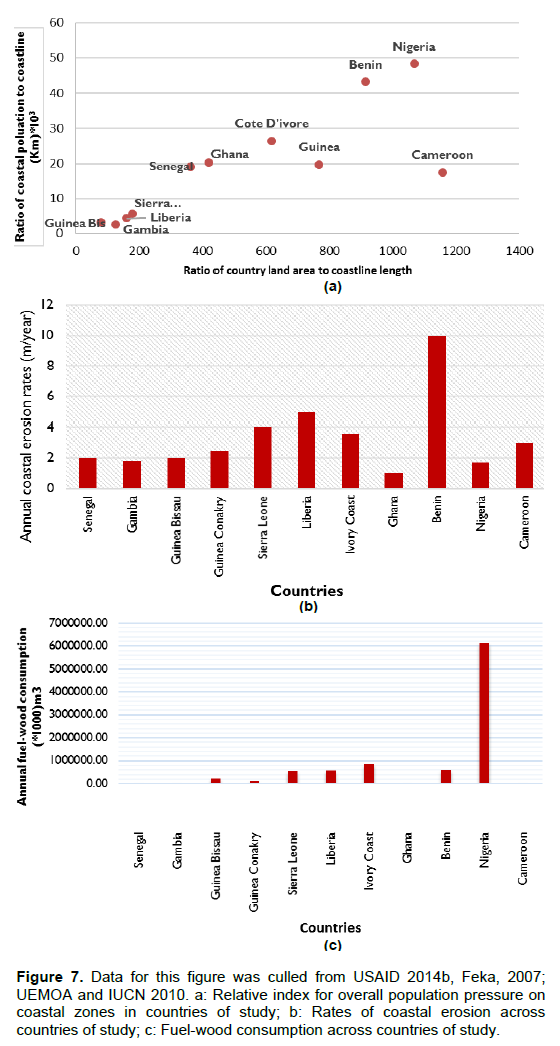

This growing coastal population is increasing pressure (Figure 7a) on the coastal ecosystem resources, particularly mangroves across countries of West Africa and Cameroon. For instance, coastal agriculture is expanding, and most of these countries depend on farming and the exploitation of other natural resources for economic posterity. Crops which are commercially cultivated in and around coastal ecosystems in the region include cashew nuts, coconuts, rice, and palms. In 2012, cashew plantations accounted for 2,230 km2 of the agricultural landscape of Guinea-Bissau, of which over 60% are mangrove swamps (Catarino et al., 2015), and clearing of mangrove forests for rice-cultivation have transformed over 2,280 km2 of mangrove forests across six countries of this region (Agyen-Sampong, 1994). Palm oil expansion is a known threat to the mangroves of South East Asia (Giri et al., 2014; Richards and Friess, 2016), and this study also identified that this threat is gradually creeping into the mangrove swamps of Benin, Cameroon, Ivory Coast and Sierra Leone. As mangrove forests are cleared, the land is exposed and eroded by rising sea tides and precipitation at varying rates (Figure 7b), with a mean loss of 3.33±2.50 m year-1 in countries of West Africa and Cameroon (USAID, 2014a).

In countries of West Africa and Cameroon, increasing demand for fisheries has led to reduced catch per unit effort across countries of the region (Lenselink and Cacaud, 2005; Béné et al., 2007). Thus, there is increasing scarcity of fish in these coastal waters, which is forcing local fishers into migratory lifestyles, as they begin to move from country to country to meet up with household and economic needs (UNEP, 2007; Duffy-Tumasz, 2012). These dwindling fish stocks, coupled with the migratory behaviour of coastal fishers increases the vulnerabilities of local households to poverty, disease and instability (Béné et al., 2007; USAID, 2014a). Mangrove wood is also persistently depleted by the fishing sector as a source of energy for basic household needs such as fish-smoking and cooking as seen in Figure 7c which shows the current fuel-wood quantities consumed annually in countries of the region. National data on the use of fuel-wood from mangrove forests and other coastal ecosystems is either scarce, or unavailable, but the exploitation and use of mangrove is well documented as a primary driver of mangrove forest loss across countries of the region (CEC, 1992; Kjerfve et al., 1997; Macintosh and Ashton, 2002). It is, therefore, essential to focus on improving national and regional data on mangrove wood exploitation and use, as well as to develop a database to make this information publicly available to the right stakeholders.

This establishment of coastal; industries, infrastructural development, agricultural expansion coupled with the parallel increases in coastal population has direct implications on the effectiveness of conservation efforts. These developments cumulatively increase the need for adequate amenities to meet needs of industries and human welfare at this environmental edge. These additional pressures are compounded by poor design or poor planning in the construction of these amenities (UNEP, 1999). This lack of strategic planning comes from inadequate or ineffective environmental policies across countries of the region (Diop et al., 2014). These policy failures facilitate poor practices, such as the voluntary discharge of solid or liquid material into coastal ecosystems by industries and domestic households (Abe et al., 2002). The effects of these discharges synergize with the already pressurized ecosystems to accelerate the chemical modification of coastal waters. For instance, over 2,571,114 m3 of oil was spilt into the Niger Delta since the 1980's (Egberonge et al., 2006). These oil spills can have acute and chronic effects on coastal biodiversity, with a resident time of up to ten years and a probability to drastically reduce sea turtle populations in the Niger Delta (Luiselli et al., 2006). Oil spills are damaging the aquatic environment by loading the water, sea animals, plants and adjacent farm soils with toxic heavy metals. This spillage is potentially dangerous to humans and their livelihood strategies as it leads to contamination and destruction of fish and farmlands (Nwilo and Badejo, 2005). These spills, coupled with oil exploitation operations have depleted about 40% of the mangrove forests in the Niger Delta in Nigeria (Langeveld and Delany, 2014).

At the household level, the Ebrié Lagoon in Abidjan is host to about 3.5 million people, who dump destructively large quantities of untreated domestic sewage into this site (Abe et al., 2002). Consequently, the Ebrié lagoon is facing drastic increases in eutrophication, especially in the bays, which affects marine and coastal biodiversity. Continued disposal of plastics, discarded fishing gear, packaging materials, and other debris, has led to an estimated 4.0 million tonnes of solid waste across the Gulf of Guinea (Ukwe et al., 2006). Immediate implications resulting from these increasing levels of pollution include high Biological Oxygen Demand (BOD), estimated at 47,269 tonnes in the Gulf of Guinea (UNEP, 2000). These effluents affect the development of coastal ecosystems and may impede conservation efforts.

Climate change: The effects of climate change are already visible in the coastal zones of countries of West Africa and Cameroon, and the IPCC (2001); IPCC (2007) predicts that in the coming years, events resulting fromclimate variability will be more frequent and intense when compared to previous years. However, the effects of climate variability on the coastal ecosystems of the region predate the 1990s when serious droughts caused the depletion of vast areas of mangroves in Senegal and Guinea-Bissau (Jallow et al., 1996; Jallow et al., 1999; Sakho et al., 2011). Over time, increasing precipitation levels, compounded by pests and crop diseases around rice paddies led to widespread losses of agricultural productivity in 70% of the cultivable land, and losses of coastal biodiversity in Guinea-Bissau (Da Silva et al., 2005; FAO, 2007). Sea-level rise and oceanic temperature increases have from the warming atmosphere have become a prominent threat to the coastal zone of West Africa and Cameroon (UMOUA and IUCN, 2010; Diop et al., 2014). Rising sea levels, coupled with increased levels of precipitation will increase the risk of flooding in low-lying coastal cities from Ghana to Nigeria and result in property losses, human displacement, dislodging of economic infrastructures and upsetting the coastal fishing industry and tourism (Ibe and Awasiko, 1991; Gabche, 2000). Flooding has already destroyed agricultural lands, salinized drinking water sources and deformed landscapes in Cameroon and the Gambia (Jallow et al., 1996; Munji et al., 2013). Also, even slight changes in average temperature are causing dieback to mangrove forests of Benin and Cameroon (Government of Benin, 2007; Ellison and Jouah, 2012). Climate change is impacting local coastal livelihood strategies of coastal communities and infrastructures

across countries of the region as elucidated by this study. These climate change effects are also synergising with anthropogenic drivers to exacerbate coastal ecosystem loss (Gabche et al., 2000; IPCC, 2007; Dickinson, 2015). In this way, climate change undermines the planning implementation and conservation outcomes of interventions.

Coastal ecosystems in the countries examined in this study continue to represent a source of socio-economic and ecological opportunities to various local and international stakeholders. Regardless of these possibilities, these ecosystems are now, more than ever, under mounting anthropogenic pressures of different types. These threats are undermining the very existence of these ecosystems as well as the opportunities they offer to humanity. Various institutions have been taking actions to address these threats in countries of West Africa and Cameroon. These institutions implemented a series of mangrove focused interventions with a broader aim of sustaining coastal ecosystems. This study argues that focusing on the efficient management of mangroves, has the advantage of enabling practitioners to monitor and collect information and data that can be used as bio-indicators to predict the overall health and provide clues to the management of other coastal ecosystems and biodiversity.

Interventions implemented to manage mangroves across countries of West Africa, and Cameroon varied considerably in scope and type (Table 5 and Annex 1). How these interventions contributed to overall mangrove and coastal ecosystem sustainability was influenced by various internal (that is, implementing institutions) and external factors (that is, economic, political and climate). The most important drivers of intervention successes included; growing international interest in mangrove ecosystems across the region, and financial support, coupled with a research interest in some of these countries. At the same time, lack of adequate monitoring and reporting of intervention results and lack of basic data to support informed decision-making, along with the lack of sound sustainability strategies in conservation interventions, poor collaboration between local and national institutions, and governance deficiencies were major constraints that restrained institutions from delivering successful field interventions.

Outside the institutional frames, the lack of sustainable funding by implementing institutions and lack of enabling policies promoting mangroves and other coastal ecosystem management favoured and catalysed unsustainable practices that deteriorated these ecosystems and prioritised infrastructural development over conservation and preservation initiatives. Past and ongoing initiatives undertaken to curb drivers causing coastal ecosystem change across countries of the region are slowing the rate of mangrove forest loss as elucidated by this study. However, this recovery of mangrove forests is not reflected in the state and health of other coastal ecosystems across countries of the region. The connecting role of mangrove forests at the coastline interface to other coastal ecosystems means that this inconsistent recovery may have external links on other systems. This study has identified that this might be the result of factors outside the scope of conservation interventions such as; unsustainable economic trends, pressure from population growth, lack of inadequate legal policies and ineffective enforcement of existing legislations. These governance failures are promoting the unsustainable exploitation of coastal resources, pollution, coastal erosion and hence depletion of coastal ecosystems across the region. Also, the effects of these direct anthropogenic drivers are exacerbated by climate change and are anticipated to have far-reaching implications on local livelihoods and economic development across countries of the region.

These findings suggest that to effectively address current threats affecting coastal ecosystems across countries of the region, business-as-usual conservation actions are no longer sufficient. Institutions need to improve the effectiveness of traditional conservation practices, and redouble their conservation efforts as well as develop integrated strategies that broadly consider all activities that affect these systems, vertically and horizontally, within and outside countries. For this to happen, the governments of these countries and international organizations will need sustained political and financial support. This support must be a collective effort by national governments, international agencies, regional institutions, academia, national and international NGOs and corporate institutions working through a common platform. Indicators of this concerted effort should include legislative reforms on policies that promote; efficient management of mangroves, other coastal ecosystems, and improved environmental governance by industries operating at this coastal edge. Failure to expand current conservation efforts and facilitate legislative reforms for the systems under which mangroves and other coastal ecosystems are managed is likely to undermine the potentials of these systems in other national strategies.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Abe J, Kouassi M, Ibo J, N'guessan N, Kouadio A, N'goran N, Kaba N (2002). Cote d'Ivoire Coastal Zone Phase 1: Integrated Environmental Problem Analysis. Global Environment Facility GEF MSP Sub-Saharan Africa Project (GF/6010-0016)

|

|

|

|

Adekanmbi HO, Ogundipe O (2009). Mangrove biodiversity in the restoration and sustainability of the Nigerian natural environment. J. ecol. Nat. Environ. 1(3):64-72.

|

|

|

|

Adger NW, Brown K, Fairbrass J, Jordan J, Paavola J, Rosendo S, Seyfang G (2003). Governance for sustainability: towards a `thick' analysis of environmental decision making. Environ. Plan. 35:1095- 1110.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Adite I, Imorou T, Gbankoto A (2013). Fish assemblages in the degraded mangrove ecosystems of the Coastal Zone, Benin, West Africa: Implications for Ecosystem Restoration and Resources Conservation. J. Environ. Prot. 4(12):1461-1475.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Adite A, Abou Y, Sossoukpê E, Fiogbé ED (2013a). Oyster farming in the coastal ecosystem of Southen Benin (West Africa) Environment Growth and Contribution to Sustainable Coastal Fisheries management. Int. J. Dev. 3(10):87-94.

|

|

|

|

Agyen-Sampong M (1999). Mangrove swamp rice production in West Africa. Dynamique et usages de la mangrove dans les pays des rivieres du Sud (du Senegal a la Sierra Leone). C. S. Marie-Christine. Paris, ORSTOM: 185-188.

|

|

|

|

Ajonina G (2010). A Decade of Mangrove Reforestation in Africa (1999e2009): Series One, an Assessment of in Five West African Countries; Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria and Senegal (African Mangrove Network/R_eseau Africain pour la conservation de la mangrove, Dakar Senegal).

|

|

|

|

Akegbejo-Samsons Y (2009). Management challenges of mangrove forests in Africa: a critical appraisal of the coastal mangrove ecosystem of Nigeria. Nat. Faune 24.1.

|

|

|

|

Alongi DM (2008). Mangrove forests: Resilience, protection from tsunamis, and responses to global climate change. Estuar Coast Shelf Sci 76 1e13

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Alongi DM (2014). Carbon Cycling and Storage in Mangrove Forests. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2014. 6:195-219.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Armah AK, Adomako JK, Agyapong EK (1997). Towards sustainable management of mangroves in Ghana. UNIDO/UNDP/NOAA/UNEP Gulf of Guinea/Large Marine Ecosystem Project Newsletter. No. 6: 9â€10. Abidjan, Cote d'Ivoire.

|

|

|

|

Aung TT, Mochida Y,Than MM (2013). Prediction of recovery pathways of cyclone-disturbed mangroves in the mega delta of Myanmar. For. Ecol. Manage. 293:103-113.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Baba S, Chan H, Aksornkoae S (2013). Useful products from mangrove and other coastal plants. ISME Mangrove Educational Book Series No. 3.

|

|

|

|

Béné C, Macfadyen G, Allison EH (2007). Increasing the contribution of small-scale fisheries to poverty alleviation and food security. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Rome, FAO fisheries technical 481p.

|

|

|

|

Blasco F, Saenger P, Janodet E (1996). Mangroves as indicators of coastal change. Catena 27, 167-178.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Brenon I, Monde S, Pouvreau N, Maurin JC (2004). Modeling hydrodynamics in Ebrié lagoon, Côte d'Ivoire." J African Earth Sce 39.3-5 (2004): 535-540.

|

|

|

|

BSP (1993). A framework for integrating biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. Washington, DC: Biodiversity Support Program (BSP), 1993-Carreiras J, Maria MB, Vasconcelos J, Richard LM (2012). Understanding the relationship between aboveground biomass and ALOS PALSAR data in the forests of Guinea-Bissau. Remo Sensing of Environ.121:426-442.

|

|

|

|

Catarino L, Menezes Y, Sardinha R (2015). Cashew cultivation in Guinea-Bissau – risks and challenges of the success of a cash crop. Scientia Agricola, 72(5), 459-467.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

CBD (2009). Connecting Biodiversity and Climate Change Mitigation and Adaptation: Report of the Second Ad Hoc Technical Expert Group on Biodiversity and Climate Change, Montreal.

|

|

|

|

CEC (1992). Commission of the European Communities (CEC), Directorate-general for Development. Mangroves of Africa and Madagascar. Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, Brussels (Luxembourg).

|

|

|

|

Chan HT, Baba S (2009). Manual on guidelines for rehabilitation of coastal forests damaged by natural hazards in the Asia-Pacific region. ISME, Okinawa, Japan, and ITTO, Yokohama, Japan.

|

|

|

|

Choudbury JK (2002). Sustainable Management of Coastal Mangrove, Forest Development and Social Needs F.A.O. Rome pp. 265-285.

|

|

|

|

CIA (2016). The World Factbook.

View

|

|

|

|

Cormier-Salem M-C (eds.) (2014). Participatory governance of Marine Protected Areas: a political challenge, an ethical imperative, different trajectories. S.A.P.I.EN.S [Online], 7.2 | 2014,

View

|

|

|

|

Da Silva SA, da Silva CS, Biai J (2005). Contribution de La Guinee-Bissau à L'élaboration d'une Charte Sous-Regionale Pour Une Gestion Durable des Ressources de Mangroves. IUCN /IBAP Guinea-Bissau

|

|

|

|

Daan B, Grigoras I, Ndiaye A (2006). Land Cover and Avian Biodiversity in Rice Fields and Mangroves of West Africa. Prepared for Wetlands International West Africa Program for Southern Senegal to Sierra Leone

|

|

|

|

Dahdouh-Guebas F, Jayatissa LP, Di Nitto D, Bosire JO, Lo Seen D, Koedam N (2005). How effective were mangroves as a defense against the recent tsunami? Curr. Biol. 15, R443–R447.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dahdouh-Guebas F, Van Hiel E, Chan JC, Jayatissa LP, Koedam N (2005a). Qualitative distinction of congeneric and introgressive mangrove species in mixed patchy forest assemblages using high spatial resolution remotely sensed imagery (IKONOS). Syst. Biodiv. 2:113-119.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dan TT, Chen CF, Chiang SH, Son NT, Chen CR, Chang LY (2015). Change detection of mangrove forests in west and central Africa with Landsat imagery. conference paper

|

|

|

|

Das S, Crépin AS (2013). Mangroves can provide protection against wind damage during storms. Estuary Coast Shelf Sci 134: 98–107.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

de Lacerda, LD (eds) (2002). Mangrove ecosystems: function and management. Berlin: Springer, 2002.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Dickinson M (2015). Climate change and challenges Grantham publications.

|

|

|

|

Din N, Saenger P, Priso RJ, Dibong DS, Blasco F (2008). Logging activities in mangrove forests: A case study of Douala Cameroon. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol 2(2):22-30.

|

|

|

|

Diop MD, Ikonga J, Ndiaye A (Eds.) (2006). Priority Conservation Actions for Coastal Wetlands of the Gulf of Guinea: Results from an Eco-regional Workshop. Senegal Wetlands International, Dakar. Business Centre, Stratford Road, Moreton-in-Marsh, GL56 9NQ, United Kingdom.

View

|

|

|

|

Diop S et al (eds.) (2014). The Land/Ocean Interactions in the Coastal Zone of West and Central Africa, Estuaries of the World,

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Duffy-Tumasz A (2012). Migrant fishers in West Africa: roving bandits?" Afri. Geogr. Review 31.1: 50-62.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Egberonge FOA, Nwilo PC, Baddejo OT (2006). Oil spills disasters monitoring along Nigerian coastline. 5th FIGURE regional conference Accra, Ghana March 8-11, 2006

|

|

|

|

Egnankou MW (2009). Rehabilitation of mangroves between Fresco and Grand-Lahou (Côte d'Ivoire): Important fishing areas. Nature & Faune 24.1 (2009).

|

|

|

|

EJF (2013) The Governance of Artisanal Fisheries in the Sherbro River Area of Sierra Leone. A report by Environmental Justice Foundation.

View

|

|

|

|

Ellison JC, Zouh I (2012). Vulnerability to Climate Change of Mangroves: Assessment from Cameroon, Central Afr. Biol. 1: 617-638.

|

|

|

|