Woodlands of Ethiopia are estimated to be around 70%. Unfortunately, this woodland is seriously under threats, mostly linked to human interference, livestock and climate change. To overcome these problems, protected woodlands were implemented in different parts of the country including Dugda Woreda Giraba KorkeAdii Kebele. However, the perception of local community towards protected woodlands was not studied. As a result, the main purpose of this study was to assess the perception of local community toward protected woodland at Dugda Woreda, East Shoa Zone, Oromia, Ethiopia. Before deciding the method of data collection, a reconnaissance survey was undertaken to obtain the impressions of the study site conditions and select sampling sites. A purposive sampling technique was employed to select the kebele from the Woreda. The sample size of households for the survey was determined by the proportional sampling method. A total of 138 households were selected for the survey; of these, 61 households are poor, 53 households are medium in terms of income and 21 households are rich. Semi-structured questionnaires were prepared for household interviews and the data were analyzed using Microsoft excel and SPSS and results were presented using descriptive statistics. Of the total respondents, 88.32% had positive attitudes towards the protected woodland practices. However, various problems were also identified such as shortages of firewood (83.34%) and scarcity of pastureland (74.64%) and poor infrastructure which are challenges to the sustainability of protected woodland for the future.

Woodlands once covered over 40% of the global tropical forest areas (Mayaux et al., 2005) and 14% of the total African surface. Their proportion of the landmass of Ethiopia is estimated to be around 70% woodland (Endale et al., 2017). Ethiopia owns diverse vegetation resources that include high forests, woodlands, bush lands, plantations, and trees outside forests. Next to forest resources, protected woodlands represent a huge

wealth of biological resources (Zegeye et al., 2011). The DugdaWoreda woodland has benefited the local community by providing or supplying the dominant part of the pasture, fuel wood, medicinal, honey production and as well as serving as the habitat of biodiversity. In the Central Rift Valley of Ethiopia, the natural vegetation is mainly made up of Acacia-dominated woodland, a highly fragile ecosystem adapted to semi-arid conditions with erratic rainfall, growing on a complex and vulnerable hydrological system (Hengsdijk and Jansen, 2006). Unfortunately, these woodlands are being lost at an alarming rate (Pimm et al., 2006; Jhariya et al., 2014; Kittur et al., 2014; Negi et al., 2018).

Understanding of farmer’s perceptions about natural resource management is one of the important factors to be able to develop effective conservation intervention. Community participation ion woodland resources management helps to create a platform to enhance dialogues and negotiations among farmers and outsiders (Wegayehu, 2006).. Any endeavor attempting to develop sustainable and effective conservation of woodland, rules, regulations, institutions and strategies need to take farmers’ perceptions of land use into account (Tefera et al., 2005). The objective of this paper was to highlight the perception of the local community to protected woodland for a sustainable land use system.

Description of the Study area

The study was carried out in Dugda Worda, Giraba Korke Adi Kebele. Giraba Korke Adi Kebele is located at 8°6’00’’ to 8°10’ 00’’ N Latitude and 38o42’30’’ to 38°51’30’’E Longitude (Figure 1). The administrative seat of the Woreda is Meki town, which is located 132 km from Addis Ababa along the main road that goes through Mojjo to Hawassa. The Woreda is bordered with SNNPRS to the West, Zeway Dugda Woreda to the East, Bora Woreda to the North and Adami Tullu Woreda to the South (CSA, 2012).

Methods of data collection

Sampling design and sampling techniques

A preliminary reconnaissance survey was undertaken in the first week of November 2017 in order to obtain the impressions of the study site conditions and to select sampling sites. During this period, overall information on the study site was obtained and the sampling method to be used was identified. The purposive sampling technique was employed to select the kebele from Woreda because of woodlands that have been extensively protected for a long period. Kebele refers to the smallest governmental administrative unit of the Woreda in the study area. Local people’s perception about protected woodland is significantly influenced by the economic condition of the farmers. Thus, wealth status was used as the criterion to stratify households into different economic categories for the survey into ‘poor’, ‘medium’ and ‘rich’ wealth categories with the assistance of the Key Informant (Table 1).

After stratifying sample households based on the wealth criteria, a representative sample size of the respondents was determined by using Yamane’s formula (Yamane and Sato, 1967). Thus;

To determine sample size in terms of the number of respondents, the researcher employed the proportional sampling technique and a total of 138 HH samples were selected proportionally (Table 2)

Data collection techniques

Data collection was conducted starting from November 2017 to May 2018. Data were collected using household surveys, key informant interviews, field observations, and focus group discussions (FGD). These are the most important data collection methods to measure attitude or outlook and perception of local communities for protected woodland.

Household survey

The sample respondents from the selected households were selected by using proportional sampling, which was conducted by giving codes for all households to be selected. After completion, the questionnaire was distributed to 138 households. Different age groups, educational background, distance from the protected woodland, and source of income were included in the questionnaire. Questionnaires were translated into local language to “Afaan Oromo”. Before performing the interview, half day training was given for the data collectors on how they can collect valuable data for the research.

Key informant interview

The Kebele tour was made with selected community members and development agents. During the tour, ten randomly selected farmers were asked to give the names of five key informants who had lived in the area for long and were assumed to have adequate knowledge of their locality. From the total list, five key informants who were frequently mentioned were selected. Key informants were used to categorize randomly selected households into wealth ranks through local criteria and to collect further information on the management and uses of woodlands. The data collected from key informants were used as the triangulation method and are not included in the analysis.

This form of interview used less strictly formulated questionnaires that can provide the participants with a more relaxed atmosphere to express their thought. In selecting key informants, the first step was to identify the relevant groups from which they can be drawn. The second step in this process was to select a few informants from each group. The common practice is to consult several well-oriented persons in order to prepare a list of the possible informants. The list was large enough to include substitutes in case some informants were not available. During the interviews, key informants tend to suggest names of other persons who, in their opinion, are excellent key informants.

Focus group discussion

The FGD was used as a complementary to the household survey. FGD participants were selected based on their age, knowledge about the area and duration of residency in the study area (Girma et al., 2010). Community leaders and local translators participated for better achievement of discussion. Information collected from group discussion was summarized using a text analysis method.

Field observation

For the sake of getting adequate and relevant information about the perception and attitude of local communities, observation of what people were doing in their daily activities for their livelihoods, an overview of their living environment, and interaction of local communities with the protected woodland were conducted. Moreover, observations of what people have and do not have, and who does exploration of what local people do, when and for how much, were assessed for the identification of major reasons for conflict.

Source of data

Primary and secondary data were employed.

Primary data

Primary data were collected through questionnaires and interviews. The semi-structured questionnaires were designed to obtain from the community the perception of society toward protected woodland.

Secondary data

Secondary data were obtained largely through the analysis of various documents relevant to the study both from published and unpublished documents. This includes institutional reports, books, records, and journals/papers/articles which provide baseline information for the study.

Data analysis and presentation

The data gathered from the household survey were analyzed using SPSS 16.0 and Microsoft excel to understand the perception of the local community toward protected woodland, the local community, management practices, and the current condition of protected woodland. Data obtained from key informants, and field observations were used as supplementary information for the formal survey. Finally, results were presented in descriptive statistics which include: tables, percentages graph, diagrams/charts as needed to show the number of households corresponding to their responses towards protected woodland.

Socio-economic characteristics of the respondent

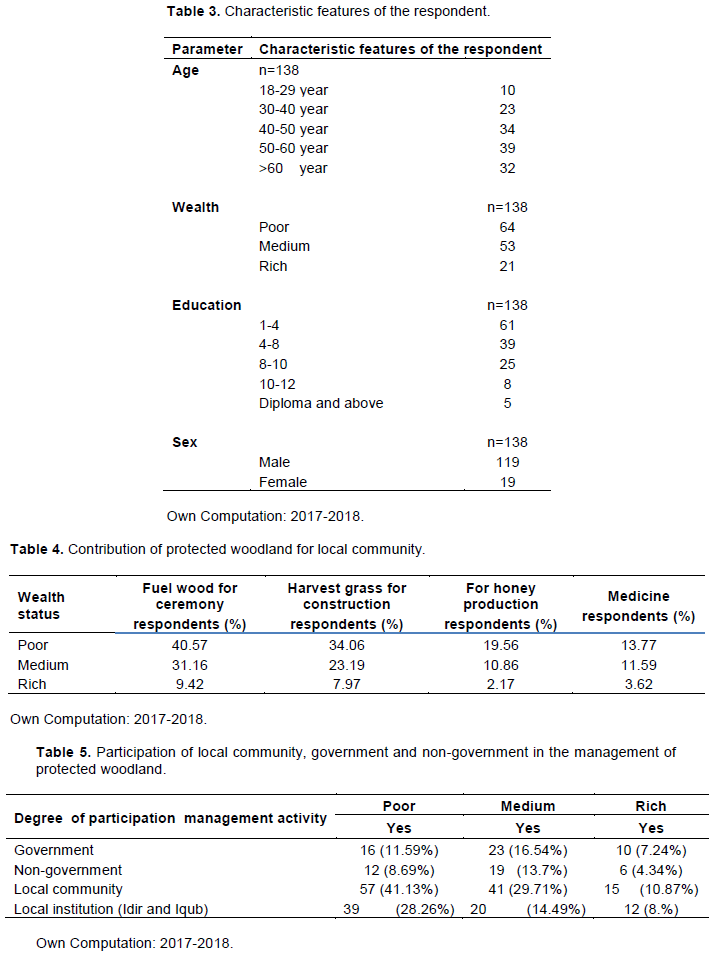

Household characteristic of the respondent: Age, Education status, wealth categories and sex are given in Table 3). Majority of the respondents (86.2%) were male household and 13.8% of the total respondents’ female headed households. In Giraba Korke Adiikebele, 7.25% of the respondents were young (18-29 years old), 41.31% were adult (30-50) and 51.45% were old (>50 years old). The age of most respondent (92.75%) in the study area ranged from 20-60 years old with the mean age of 46.5% years. From the total number of respondents (n=138), 46.38% households were poor, 38.41% households were medium and 15.22% households were rich by wealth status. The education level of most respondent (76%) was having attended primary school (1-8 class) (Table 3).

Benefits of protected woodland to the local community

From the total of respondents, 81.15% indicate that protected woodland provided fuel wood, whereas 65.22% benefited from grass harvest for construction (Table 4).

Management practice of protected woodland

Management activities as indicated by the most respondents would be necessary for the attainment of the objectives of protected woodland. About 81.88% of the respondents said that protected woodlands are properly managed by the local communities. However, the remaining (18.11%) of the respondents had no detailed information about the management practices of the protected woodland (Table 5). Majority of interviewees showed their happiness for the current management activities but the medium and poor farmers in the communities participated highly in management practices. This is because the medium and poor farmers need to harvest more grass for construction of houses and the source of income were small than for the rich farmers.

Management challenges of protected woodland

In the study area, there is a scarcity of fuel wood, grazing land, road accessibility to protected woodland and less attention were given by government to protected woodland are the main challenges that hinder the sustainability of these resources. These problems that hinder the sustainability were discussed accordingly; 83.34% of the respondents identified shortage of fuel wood, 74.64% shortage of grazinge land, 68.11% poor infrastructure, 94.33% climate change ( jijjirama qillensa in Local language by Afaan Oromo), 19.56% less government participation which are the major challenges found in study area (Table 6).

Causes of woodland degradation

The major causes of degradation of protected woodland are camel intervention, expanded crop land, illegal tree cutting and over- grazing. Accordingly, 51.45% of the respondents identified that camel intervention was the major problem for protected woodland mostly in the winter season. Similarly, 19.57% of the respondents indicated that expanded agricultural land, 13.77% illegal tree cutting, 5.8% over grazing and 0.72% charcoal production are other causes of degradation of protected woodland (Figure 2).

Attitude of local community toward protected woodland

From the total number of respondents (N=138), 88.39% had a positive opinion for provisions they get from protected woodland and were interested in amending the management practices of protected woodland in the future (Table 7). This implies that large numbers of the communities have a constructive outlook towards the protected woodland practice as means of provision of fuel wood during mourning, weeding, grass contribution for construction, and as a source of income, reducing soil erosion and by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and reducinge climate change (Figure 3).

The main provisions of the woodland for the local community were fuel wood and grass. After the grass was harvested, the woodlands were allowed to be grazed only by oxen. Even though a large number of the local community have a positive attitude toward protected woodland, about 5.07% of the respondents complained that there is unequal distribution of benefits particularly in protected woodland as they indicted in Table 6.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.