Zaria, located in Kaduna State in the northern part of Nigeria (11° N; 13°E) is among the major urban centres in the country (Figure 1). It has an estimated population of 850, 000 based on the projections of the last national census in 2006 which estimated a growth rate of about 6% per annum. Several educational institutions as well as military and commercial establishments are also located in the city. It serves as the most significant educational centre in the northern part of the country. The city covers an area of about 300 km2 and is administered through two local government authorities, Zaria (Old) City and Sabongari, roughly covering the old pre-colonial and the post-colonial sections respectively. The city in general has acquired a cosmopolitan character with inhabitants from a cross section of all ethnic groups in the country. However, the Hausa-Fulani ethnic group, who are predominantly Muslim, are dominant especially in the old city.

History

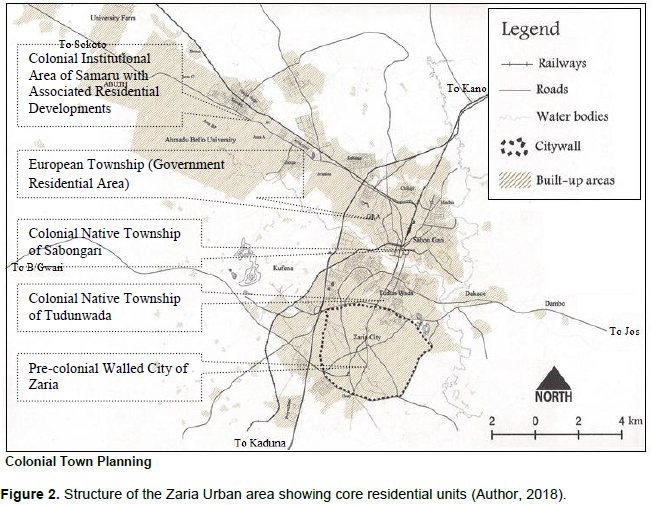

The old city, with a characteristic medieval wall around it, is among the ancient settlements of the Hausa people founded since the pre-colonial period. Until the advent of colonial rule (1903), the city had existed as the seat of administration and centre of learning, commerce and religion of the Zazzau Kingdom - one of the initial seven Hausa states in the Northern part of present day Nigeria. Colonialism and the associated policy of separating native from non-native populations brought about the emergence of settlements outside the walled city. Thus, the composition of the urban area can be described with respect to its main historical core units, which include the residential areas of the pre-colonial walled city and three colonial townships. Within these, and around their periphery, several public institutions and commercial areas have been established mainly during the colonial period. Extensions, both and spontaneous have also proceeded around their peripheries during the post-colonial period to accommodate the growth of the urban area (Figure 1).

In the ranks of colonial forts, Zaria served as a provincial headquarter of the Zaria Province, a position that bestowed upon it a second-class township status under the 1917 Township Ordinance. It is at the centre of a major agricultural region linked by rail right from the beginning of the colonial era to a network of railway service in the country. It was also a major garrison town of the British, through the West African Frontier Force (WAFF), for which it hosted an army training school that exists to date as one of the major military institutions in the country. The combination of its history as the seat of the Zazzau Kingdom prior to colonisation and its colonial status as a major administrative, military and commercial centre bestowed the city with a dual identity, reflecting both pre-colonial and colonial embodiments, in the same genre as the classical dual city settlements. Similar duality in identity has been reported in much of British colonial outposts around the world (King, 1976; Urquhart, 1976).

Colonial Town Planning

In Zaria, the colonial township development policy was implemented through the creation of three categories of new townships based on an elaborate plan that reflects the footprints of the township ordinance, generally applied to all colonial cities in Nigeria. The ordinance sought to configure the major administrative and commercial headquarters in cities throughout the country in a defined physical form that facilitates their functions. This was based on a common concept separation of residential areas and a general specialisation of land uses. This concept became the blueprint on which new settlements were established and existing ones, like Zaria, adapted to.

Prior to the ordinance, other legislations had paved the way for what eventually became a general blueprint for town planning across the country. In particular, the Cantonment Proclamation of 1904 (at the early stages of colonial rule) had been credited with setting the stage for further legislations including the 1917 Township Ordinance in that direction (Aluko, 2011; NITP, 2012). The 1904 Proclamation provided for the separation of the living quarters of the European (Colonial) population from the native population. This separation crystallised into the creation of European Residential Areas (Described later as Government Residential Area - GRA) separated usually by a track of open space from the native areas. In between were located institutional and commercial areas, which generally became the hubs of the settlements.

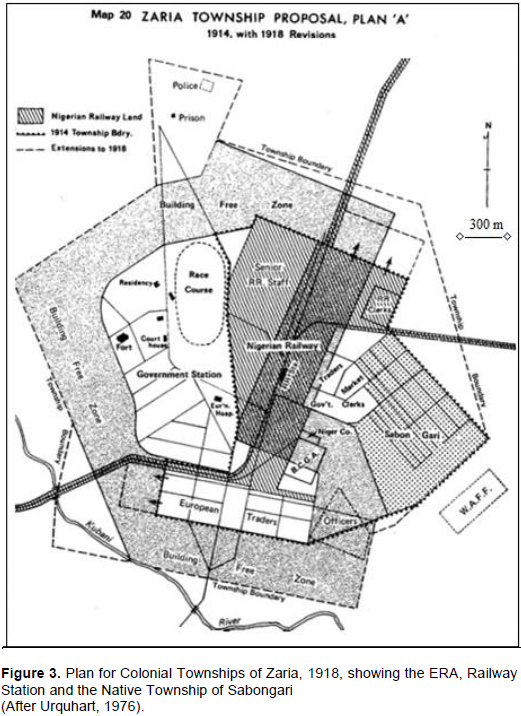

The 1917 Ordinance became the main tool for implementing this concept and it added to it provisions for the accommodation of different categories of the native population itself as in the case of Zaria, along ethnic lines. It turned out to be the main pivot for the implementation of colonial town planning policies that has to date made the most profound impression on the layout and structure of most cities in Nigeria especially in the realm of modern town planning. Land use specialisation was reflected in the demarcation of institutional areas, modern commercial areas, open spaces and residential areas for different categories of indigenous and European populations (Urquhart, 1976; Ambe, 2007). The blueprint that emerged crystallised into four units in Zaria, consisting of the European Residential Area and surrounding open space buffer, public institutional areas, modern commercial and light industrial area and the three native townships of Sabon Gari, Tudunwada and Samaru (Figures 2 and 3).

These components reflect the basic features of all colonial townships across the country and among all the categories of classes, with variations only in detail and scale from town to town. However, in the pre-colonial cities of Northern Nigeria like Zaria, Kano and Katsina, there were the old city sections, with walls, existing largely uninterrupted in their physical form. This category of cities became conglomerations consisting of three main units - the Old city with characteristic wall; the European settlement (GRA) which also includes government offices and trading plots; the African non-Northerner settlements of Sabon Gari; and the non-native Northerners settlement of Tudun Wada. Each was being treated as a separate unit in both the administrative and the town planning sense (Rollison, 1958; Urquhart, 1976).

The 1917 schema was crystallized in Zaria though a series of plans proposed by the colonial administration first in 1914 and revised in 1918 and 1939 addressing the main European Residential Area (ERA) and associated land uses. Shown in Figure 3, this was the basic prototype plan encapsulating key provisions of the Township ordinance. It includes provisions for very large (an acre or more) plots of residential land in the European section around the centre, a railway line and station linking Zaria with the cities of Kano in the North and Kaduna in the south, subsequently to the port city of Lagos and a large open space serving as race course for horses and other sports. The plan also included some public institutions (court, police station), trading areas and an expansive building-free zone providing a buffer between this area and the native area of Sabon Gari, which was included in this initial plan. Other native areas of Tudun Wada and Samaru were to arise later. Post-colonial urban development and comparisons

What has ensued from 1903 to the present in terms of the configuration of the city is a labyrinth of planned and unplanned growth, with the latter accounting for most of the expansion into peripheral areas through sprawl. This has given the city a mixed form and composition reminiscent of the historical epochs in the development of each of its component units both physically and socially. What is significant about the contemporary growth is not just its scale but also the lack of planning or order that characterize it. The peripheral areas where it takes place generally seem to be developing well ahead of any formal planning intervention, and much of it occurs in contravention of the planning regulations and without basic infrastructure such as access roads and services like water supply, drainage and electricity mains. The process by which this development occurs is often in complete negation of planning and local administrative regulations and the result is the emergence of haphazard physical developments and slum-like living conditions.

An impression of the magnitude of this situation can be had when we examine the proportion of land in the urban area and spontaneous development over the course of the colonial and post-colonial period, which stands at about 70% of the present built-up area (Kugu, 2016). The growth pattern indicates characteristics depicting a clear difference between what was obtained during the colonial and post-colonial periods. Thus, while only the walled city section contained what may be described as spontaneous growth during the colonial period, a greater proportion of the urban developments are now in that category. No clear information is available on the population of these residential areas. However, it is evident from the density of buildings observable that the planned areas accommodate only a small proportion of the about one million inhabitants of the city. The GRA in particular has a tiny part of this, quite disproportionate to the land area it occupies, meaning that the bulk of the population resides in areas that are unplanned, inclusive of the old city and all the newly emerging areas on the periphery.

Most of the new developments in terms of both the population and expansion of built-up area occurred in the last few decades. AlsoIn addition, much of the physical growth is at variance with the provisions of the official master plan for the city. Indeed, the reality is that the plans for all practical purposes have scarcely been implemented at all, and the result of this is the uncontrolled and unplanned pattern of urban expansion being experienced today.

In contrast to the post-colonial developments, all settlements established during the colonial era had physical development plans covering their entire area or substantial parts of it. It is curious that this town planning legacy has not been maintained, and uncontrolled development represents the main process by which the city continues to grow. Under these circumstances, developments creep out into the periphery uncontrollably, setting in place a process that seems to be self-perpetuating. The result is what we observe presently – a paradoxical situation of the older parts of the cities being better planned than the newer parts (Figure 4).

DISCUSSIONS - EXPLAINING THE CHARACTER OF POST-COLONIAL URBAN GROWTH

The phenomenon of uncontrolled sprawl is itself not unique to Zaria or to Nigeria with startling examples given in several instances between both African Francophone and Anglophone post-colonial urban areas (Bastie and Dezert, 1991), although it appears to be less severe in the latter. This seems to be a symptom of the process of informal land development that characterises these cities. This is a negation of the antecedents of modern town planning bequeathed by the British colonial administration when one considers the circumstances under which the phenomenon of uncontrolled growth has taken place.

The concern for the emergence of uncontrolled urban expansion and its persistence as the main process of growth had been a topical issue of discourse among planners and the public at large for quite a while. Several discussion sessions of the type at various occasions have provided avenues for the expression of opinions and concern over the matter, to the extent that there is hardly any problem on the issue that has not been highlighted. We can surmise that the problem of uncontrolled urban expansion and the character of it has assumed is rooted essentially to two major factors – the character of land tenure and the process of land development in the context of weak institutional controls. This is made up of a variety of problems concerning the processes of land acquisition and planning administration and physical planning – the combination of which has been described as “spatial governance” (Ravetz et al., 2013). The effectiveness of this factor has seemingly been the most potent explanation of the results observed. Thus, weak spatial governance is associated with rapid and spontaneous high-density growth, while strong spatial governance leads to planned growth. These issues are pursued further.

Character of land tenure

The 1978 Land Use Act of Nigeria places all land in the territory of each State in the control of the Governor of the State. The Governor holds such land in trust and administers it for use and common benefit of all Nigerians (Federal Government of Nigeria, 1978). The Act stipulates that the governor shall only give statutory occupancy rights for land in both urban and rural areas, while the respective Local Governments under customary rights of occupancy may give such rights in rural areas. Therefore, the governor is empowered to grant Statutory Right of Occupancy in respect of land located both in urban as well as rural areas, while Local Governments are limited only to rural areas and in connection only with non-statutory (customary titles) which have a lesser tenure status of 30 years, while the statutory titles grant 99 years.

All landowners may apply and obtain a statutory Certificate of Occupancy, which grants title to the land for 99 years, subject to renewal afterwards. The process may involve applications for the allocation of land under a government scheme or the change of customary title to statutory title. In practice, only a very small proportion of land holding is acquired through the statutory system as stipulated in the Land use Act. For a variety of bureaucratic and technical problems, customary (informal) land ownership, also recognized by the law, remains the main mode of access to land. The implication of this is that much of the land holding is not subject to full documentation and subsequently to statutory controls in the process of development as is the case with formally acquired titles under planned schemes.

Process of land development in the context of weak institutional controls

Three main public institutions are involved in the land and planning administration systems in Zaria as in all other urban areas in Nigeria. These include the Local Planning Authority, represented in Zaria by the Kaduna State Urban Planning and Development Authority (KASUPDA), the Local Governments (Zaria City and Sabongari) and the Ministry of Lands and Surveys. Of these, the Planning Authority is the institution directly responsible for the planning and control of urban land uses.

The Planning Authority was established since the creation of the state as a successor to the defunct Kaduna State Urban Planning and Development Authority in the old Kaduna state. The edict establishing it as a planning authority was passed by the State Military Administration in 1985 (Kaduna State Government, 1985). Its primary responsibility is to plan, manage and control development in the designated Zaria Urban Area as defined by an overly ambitious radius of 20 kilometres from the centre of the city. The specific functions of the Planning Authority include the following:

(1) To administer, execute and enforce the provision of the Planning Law (initially, the 1946 Northern Nigeria Town and Country Planning Law (Northern Nigeria Government, 1946) and presently, Urban and Regional Planning Law, - Decree 88 of 1992 in the designated area (FGN, 1992)

(2) To plan, promote and secure the physical development and environmental improvement of the area by acquisition, management and disposal of land and other property and carrying out building, engineering and other operations

(3) To formulate, monitor, control and co-ordinate the physical development policies, plans and programs within the planning area.

It is clear that the existence of the Planning Authority and its functions are tied to the planning laws establishing it as cited above. Although there are major differences in the provision for the institutional structure for the administration of urban planning, both the 1946 Nigerian Town and Country Planning Law and the 1992 Urban and Regional Planning Law made provisions for the planning of all major settlements by a Local planning Authority. The planning includes general plans (Master / Physical Development Plans) and subject plans addressed to particular urban development issues or like urban renewal or the planning of new residential areas or other land uses. Both also clearly state the institutional responsibilities for the plan preparation and implementation, which rest primarily on the Planning Authority.

However, there seems to be major difficulties, both administrative and legal, constraining the performance of the planning authorities (Nwaka, 1989). Perhaps most striking evidence of this is the inability to fully implement the 1992 planning law. Thus, the law, which is a Federal law, has yet to be adopted by the Kaduna State Government where Zaria is situated. In effect, although a legally established institution, the Planning Authority’s operations are presently curtailed as far as the capacity to undertake urban planning activities as provided by the laws is concerned.

This is the precursor to the apparent ineffectiveness of planning activities by the Planning Authority as it places the institution in a rather obscure and frequently conflicting position in relation to other public institutions, notably the Local Governments. Due to this position, the institution also suffers functional identity crises in government policies, which in turn affect its capacity to attract adequate budgetary allocations commensurate with its roles. In turn, the circle of uncontrolled urban development is further entrenched as the Planning Authority, which has the technical and legal disposition to guide the growth of the city becomes powerless in the face of fast developments in land speculation and construction activities.