ABSTRACT

This study aimed to assess constraints to the success of ecotourism network in Tanzania. Following an intensive survey and literature review, data were collected from members of Tanzania Association of Tour Operators (TATO) using a semi structured questionnaire and key informant interviews and then analyzed by Chi-square. The findings indicate that the success of ecotourism networks needs a strong regulatory framework, financial and infrastructural support. Explicitly, findings may urge the government to reduce taxes and license fees. Moreover, extra effort is required to ensure availability of direct international flights, all-weather and feeder roads; to avoid unnecessary long routes, trail cycle paths as well as encourage individuals, groups and society at large to open more cultural heritage centers. The study recommends for TATO, government and stakeholders to establish and maintain high quality infrastructure, widen financial access to support ecotourism and further studies on ecotourism networks.

Key words: Ecotourism, network, Tanzania Association of Tour Operators.

In an effort to boost their economy and promote a sustainable environment, countries across the globe have embraced ecotourism phenomenon (Haralson, 2012; Anderson, 2009; Fennel, 2001). Ecotourism is regarded as a form of environmentally responsible tourism that involves travel and visitation to relatively undisturbed natural areas with the objective of enjoying, admiring, and studying nature (the scenery, wild plants and animals), as well as any cultural aspect (both past and present) found in these areas, through a process which promotes conservation, has a low impact on the environment and on culture and favors the active and socioeconomically beneficial involvement of local communities (Ceballos-Lascuráin, 1983).Most of Tanzanian visitors come as ecotourists as it is estimated that at least, 90% of tourists follow nature-based tourism (Anderson, 2010). Tanzania has more competitive advantage than neighbouring countries when it comes to ecotourism. The key competitive advantages are the country’s location, natural resources, cities and broad cultural heritage. More important, Tanzania is the only country in the world which has allocated more than 25% of its total area to wildlife national parks and protected area as compared to the world average of 4% (Tanzania Tourism Board, 2009). Consequently, ecotourism becomes an important sector in Tanzania as it contributes much to the national economy (currently about 17.2% of GDP) as well as supported about 400,000 direct and indirectly jobs, nearly one job for every additional tourist (Carlson, 2009; Netherland Development Organization- SNV,

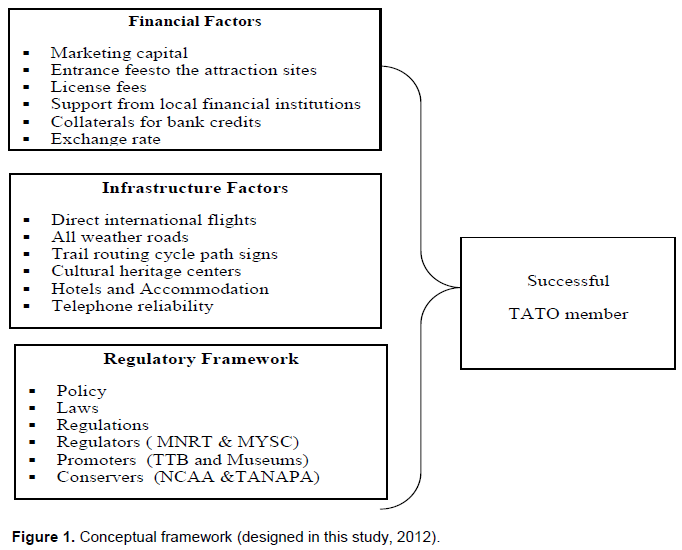

2010). According to Thome (2015), tourism is now Tanzania's leading economic sector earning US$1 billion a year, thus overtaking agriculture and growing at a steady rate for the past seven years. Tanzania's tourism is booming.As the pace of ecotourism growth in Tanzania increases, people engage themselves in this sector in various areas such as hotels and accommodation, tour guide or transportation. While some engage in ecotourism as solo practitioners, others team up to form networks such as Tanzania Association of Tour Operators (TATO), Tanzania Hunting Operators Association (TAHOA), Tanzania Hunters Association (TAHA), Hotel Keepers Association of Tanzania (HKAT) and Tanzania Hotel Schools Association (TAHOSA). This has also been attributed to the provision within the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism- National Tourism Policy (1999: 17-18) which allow stakeholders’ participation in various ecotourism related activities. Morrison et al. (2004) argued that much of tourism development is predicated on the successful working of organisations aligned in the form of partnerships or networks. However, tourism networks have been relatively neglected as an area of academic study.Despite the existence of ecotourism networks in Tanzania, still their performance is unsatisfactory and their sustainability is at high risks, the reasons being a large number of unidentified and unresolved challenges (Pasape et al., 2013). In spite of that, the potential for ecotourism networks in the country is vividly clear and in view of that, stakeholders worldwide are getting more interested in working towards addressing challenges and assure its development. For instance, following an internship for WWF Finland, Coastal East Africa Initiative Piekkola (2013) reported that the ecotourism network development in Tanzania is highly possible because of the country’s spectacular natural beauty and political stability. In order to safeguard the remaining life supporting wildlife, different stakeholders and locals should be engaged to work in cooperation seeking sustainable conservation means, such as ecotourism. Furthermore, Honey (2008) depicted that, the efforts in the marketing strategies of tourism have been able to establish an important ecotourism network in Tanzania. Thus, the major gap to be addressed is on what need to be done to ensure those networks are successful.This research therefore assessed what it takes for the ecotourism networks to succeed in Tanzania by focusing on challenges of the Tanzania Association of Tour Operators (TATO). The main objective of the study was to assess the challenges of ecotourism networks in Tanzania. Specifically, in acknowledging the success of ecotourism networks, this study assessed:

1. The role of financial factors;

2. The contribution of infrastructure support;

3. The effectiveness of regulatory framework.

The selection of TATO as the case study is because it is the largest tour network in Tanzania with more than 200 members involved in ecotourism both directly and indirectly. The association was established in 1983 to represent the licensed tour operators in Tanzania. TATO carries out advocacy for and on behalf of its members, provides a comprehensive position in its relations with the government and its institutions in matters pertaining to the formulation of tourism policy, plans and programmes. The purpose of TATO is considered important as united front to advance the interests of the private tour operators by engaging the government through dialogue in promotion of tourism, at the same time acting to promote high tourist service delivery, both nationally and internationally as revealed in Tanzania Association of Tour Operators (2015).

The main argument brought forward by this study is that, by knowing the key challenges which are facing TATO and its members, it will be easy to propose possible solutions for the benefit of TATO as well as use that experience to solve similar challenges facing other ecotourism networks. Specifically, this study intended to assess TATO’s major challenge by ascertaining the role of financial factors, evaluating the contribution of infrastructural support and determining the effects of regulatory framework in the success of ecotourism networks in the country. In order to achieve its objectives, this research tested three hypotheses as follows:

1. There is no significant influence of financial factor on the success of ecotourism networks;

2. There is no significant influence of infrastructure support on the success of ecotourism networks; and

3. There is no significant influence of regulatory framework on the success of ecotourism networks.

Literature review

Ecotourism is the fastest growing sub-sector of tourism, which emphasizes on the protection of the environment and natural habitats within its associated cultural context. It originates from the ethics of conservation and sustainable development (Miller, 2007; Weaver, 2008). In a Tanzanian context, Mgwila (2010) described ecotourism as a pro poor community based form of tourism initiative that has since its inception shown good potential for directly contributing to poverty reduction through direct tour fees, employment for local people, market for local products among other things.Ecotourism brings a lot of positive impact to communities in different areas. Buckley (2008) depicted that ecotourism is widely recognized for its positive impacts to environment, ecotourism operators and tourism lobbyists argue that the ecotourism has contributed to the economic, social and cultural development of the local communities by conserving and supporting the protectedareas. Moreover, social and cultural aesthetic/spiritual experiences foster awareness among residents and eco-tourists as revealed in Weaver (1998).For a number of years, people have been involved in ecotourism in Tanzania, Africa and globally at large. Most of those people in ecotourism have been organized through networks such as networks of tour operators, hotel owners, agents and investor as revealed in the work of Pasape et al. (2013).Anderson (2009) defined ecotourism network as a mechanism for the pooling of resources among two or more stakeholders to solve a problem or create an opportunity that neither can address individually. The value of networking to ecotourism is now widely recognized, but given the industry's constant day to day operational and time demands, its virtues as a development and growth strategy can easily be overlooked. The successful networking is not only a great marketing and customer growth tool; it is also at the heart of successful industry partnership generation. Net-working has already proved to be an essential tool for 'not for profit' tourism attractions, but even this industry sector could benefit from the extra opportunities opened.The essence of network is explained by the stakeholders’ theorists such as Donaldson and Preston (1995) with an argument that every legitimate person or group participating in the activities of a firm does so to obtain benefits and that the priority of the interests of all legitimate stakeholders is not self-evident.Despite many positive impacts of ecotourism and excellent supporting role played by ecotourism networks, still the sector is facing a number of challenges and setbacks such as in infrastructure and financial services. Davidson (1993) defines ecotourism infrastructure as physical elements that is created or made to cater for visitors. Ecotourism infrastructure also refers to the technical structures that support a society such as

roads,

water supply,

sewers,

electrical grids, telecommunications, and so forth, and can be defined as the physical components of interrelated systems providing commodities and services essential to enable, sustain, or enhance societal living conditions (Science Daily, 2012).In addition to infrastructure, finance is also assumed to be a key element in ecotourism activities. Due to the importance of financial support in ecotourism, various multinational NGOs have been invited to support the sector, for example, in 2005, Tanzania Tourist Board (TTB) and the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism being supported by a Netherland Development Organization (SNV), conducted a baseline inventory that is used in strategy development for ecotourism development. Also, according to the Citizens newspaper of March 2011, Tanzania has been receiving technical and financial support from United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) which is mainly for supporting tourism projects in the form of subsidies or micro credits with the support of local organizations.Despitethat, the remaining unsolved issue is about how ecotourism networks can benefit from such kind of assistance and under what machinery so as to enable network members to perform their tasks. This brings up the issue of regulatory frameworks. The Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism has been mandated to coordinate, support and regulate ecotourism in Tanzania through various machineries such as policies (National Tourism Policy of 1999), laws (Land, Natural Resources, Forests) and various other regulations.To date, several related empirical studies have been conducted and are reviewed by this study. For instance, Pasape et al. (2013) assessed the role of stakeholders’ collaboration strategies towards sustainable ecotourism in Tanzania mainly focusing on stakeholders’ networks and public private partnerships (PPPs). The main stakeholders’ network strategies revealed in the study were: forming more advocacy groups in the community, involving local community members (which accounted for 95.6% of all responses) followed by business and service providers; government agencies; researchers and academician in managing ecotourism (93.4%), involving stakeholders at local level (92%) and establishing networks for stakeholders’ interest (90.4%). The findings show the clear need for strong linkages among stakeholders in ecotourism networks.Along that context, Anderson and Juma (2011) conducted a study to explore challenges facing the linkages between the tourism industry and local suppliers at the destinations. During 2010, surveys were conducted in Zanzibar involving hotel and restaurant operators, local suppliers and tourists. Qualitative analysis of the perspectives of the respondents revealed a multitude of constraints. From operators, the main constraints included poor quality of the locally supplied products, business informalities, high transaction costs and violation of agreements with local suppliers. Most serious problems cited by local suppliers included lower production levels, low prices offered by hotels and restaurants coupled with late payments for the products delivered. The study also detected a certain degree of mistrust between the local suppliers and the operators. The study recommended as tools for fighting the rampant poverty strategies to bridge the demand-supply gaps in order to maximize the benefits of tourism.Besides, Dougherty and Green (2011) in their article on local food tourism networks and word of mouth made use of the surveys of three key components of local food tourism networks: farmers, restaurateurs and tourists. The study findings indicate that word of mouth is central to forming and maintaining local food tourism networks because it links farmers and restaurateurs. Also, tourists become aware of tourism opportunities primarily through word of mouth. Thus, for the success of such kind of networks, practitioners must create opportunities to link the different hubs in local food tourism networks. One of the most significant barriers to developing local food tourism networks is the lack of centralized ordering and delivery services for local food. Therefore, centralized ordering and delivery services that link local producers and food buyers may complement world of mouth-driven systems by formalizing local food tourism networks.Moreover, Anderson (2009) conducted a study on promoting ecotourism through networks with the aim of determining the roles of networks in promoting ecotourism as well as investigating other measures undertaken to implement ecotourism in the Balearics (which is an archipelago of Spain in the western Mediterranean Sea, near the eastern coast of the Iberian Peninsula). The findings revealed that as Balearic Archipelago experienced pressure from tourism activities on its resources, different stakeholders recognized the power of networking and came up with three networks known as Alucidia Network (for offering environmental education and training programmers); Sustainable Hotels Network (for promoting green environments in the hotel establishments) and Calvia Network (for focusing on individual development through ensuring active participation of hosts, control of tourism quality and sustainable use of resources). Apart from networking mechanism, the Balearic Archipelago develops a number of ecotourism instruments, policies and laws for protecting the areas affected by tourism and conserve islands soils. The study is pertinent as it provides in-depth discussion of stakeholders’ networks in ecotourism and hence contributes substantially in the networks’ studies in Tanzanian context.Furthermore, Duffy (2008) conducted a study on neoliberalising nature of global networks and ecotourism development in Madagascar to examine the power dynamics produced by the complex global networks involved in promoting and implementing ecotourism. The study pays particular attention to the increasingly close relationship between international environmental non-government organizations (NGOs) and the World Bank, and what implications such power dynamics hold for meanings and practices of participation in community-based natural resource management. In its conclusion, the study stipulates that ecotourism is appealing to a vast range of interest groups because it simultaneously seems to satisfy and speak to numerous agendas: capitalist development, community development, poverty alleviation, wildlife conservation and environmental protection. Thus, in order to understand the dynamics which underpin the expansion of ecotourism in Madagascar, it is important to examine the complex nature of the networks involved. In particular, the role of global donors, such as Co- Operation Francaise, the World Bank and international environmental NGOs in pushing forward ecotourism as a form of neoliberal development is instructive.Apart from that, Morrison et al. (2004) conducted a research on international tourism networks and draws out learning points from the examination of relatively successful examples. Among the key issues that emerge from the research findings are: structure and leadership, resourcing, engagement of participants, inter-organizational learning and sustainability. The paper concludes by identifying significant success factors and consequential management implications with specific references to tourism destinations as learning communities.In another study, Busani (2004) carried out a study on the challenges tour operators face in South Africa. The research aimed to uncover capacity and other challenges that may impede new product development in inclusive tour in Gauteng and Mpumalanga, thus prompting tourism authorities to address the identified challenges and creating an enabling environment for sustainable and responsible growth. The research findings indicated tour operators had several problems with regard to experience, lack of team work and inadequate funding. Other challenges include functional challenges such as community reluctance, economic, operational and competitive impediments. However, problems went as far as to the tourism authorities, mainly with regard to strategic and operational capacity related to the lack of expertise at Gauteng Tourism Authority and incapacitating role confusion at the Mpumalanga Tourism Authority.All these studies show the existing gaps on the needs for working on setbacks and challenges facing ecotourism networks and other stakeholders since the impacts are prominently positive and future is bright if those challenges will be addressed. This study summarizes the issues to be addressed in the form of a conceptual framework (Figure 1).

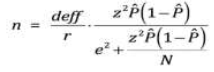

This study used quantitative design to assess the challenges faced by ecotourism networks in Tanzania. The study population comprised of all networks of ecotourism stakeholders in Tanzania, such as the Tourism Confederation of Tanzania (TCT), the Tanzania Association of Tour Operators (TATO), Hotel Association of Tanzania (HAT), Tanzania Hunting Operators Association (TAHOA) and Tanzania Society of Travel Agents (TASOTA). Others networks are Tanzania Air Operators Association (TAOA), Intra-Africa Tourism and Travel Association (ITTA), Tanzania Professional Hunters Association (TPHA), Zanzibar Tourism Investors Association (ZATI), Tanzania Tour Guide Association (TTGA) and Tourism and Hotel Professionals Association of Tanzania (THPAT). However, for the sake of focus, this study used TATO, as a sample population.In the process of establishment of sample size, various criteria can be considered, for example, a census for small populations, imitating a sample size of similar studies, using published tables, and applying formulas to calculate a sample size (Miaoulis and Michener, 1976). Considering the size of the population involved in this study, simple random sampling was adopted to guide the sampling process of which 50 respondents were randomly selected to form a study sample within the Arusha region and make approximately 20% of TATO community. The following formula was used:

Where: deff = design effect 1(for simple random sampling); r = expected response rate 0.8; z = level of confidence measure 1.96; P = baseline levels of indicators 0.5; e = margin of error 0.14; N = total population 255; Thus, n is approximated to 50.

In order to facilitate this research work, data were collected through primary and secondary sources. While data from questionnaires formed the primary data sources, secondary data were drawn from secondary sources such as the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism (MNRT), the Tanzania Tourist Board (TTB), Ngorongoro Conservation Area Authority (NCAA), Tanzania National Parks (TANAPA), Confederation of Tourism Associations (CTI), TATO and Tanzania wildlife Research Institute (TAWIRI). In addition to the semi structured questionnaire and secondary data, study also uses the key informant interview to stimulate the in-depth discussion with key stakeholders and collect relevant information. The researcher used the Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) as an analytical package whereby a descriptive and statistical method for data analysis specifically the Chi square analysis was employed to assess relationship of variables.

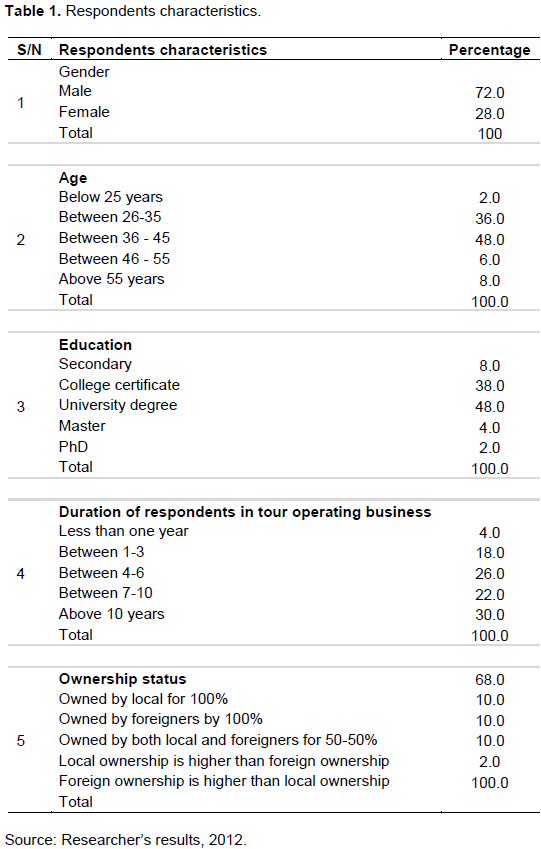

Respondents’ characteristics

The demographic characteristics (Table 1) of the study sample revealed that majority of respondents (72%) were males. With regard to age, the category between 36-46 years was the largest group (by 48%), followed by the age category of 26 to 35 years (36%). On education level, a significant proportion of the sample (48%) had a university degree level or completed certificate level of education (38%). However, less than 5% had post graduate qualification. Pertaining to the ownership structure of business, the study findings showed that 68% of tours operating companies are owned by local investors. Furthermore, with respect to the duration engaged in tour operating business, 30% of the respondents indicated that they have been engaged for more than 10 years followed by 4 to 6 years (22%).

In addition to respondents’ characteristics, the following sections present the results from the three hypotheses related to financial factors, infrastructure support and regulatory framework respectively based on the three specific objectives as follows:

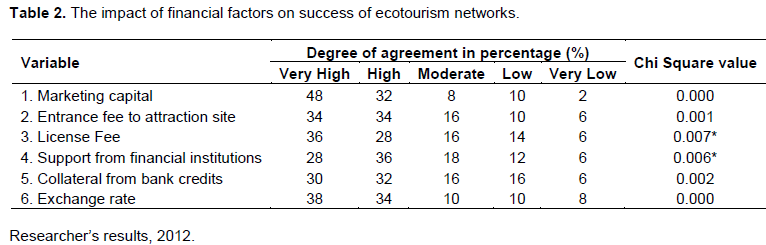

Financial challenges

The findings on specific tested financial factors (Table 2) show that inadequacy capital for marketing of tour activities affects success and sustainability of tour operationg business for over 80%, followed by the entrance fee to the attraction sites for over 68%, and inadequate support from the existing support local financial institution (for 50%) including collateral demands for over 62% as well as the weak exchange rate of local currency over other currencies. Furthermore, the research findings show that about 64% of the total respondents agreed that local financial institution affects the success and sustainability of tourism business.

In addition to the above results on the degree of agreement, the hypothesis was also tested using Chi square value and the results show that with exception of license fee and support from financial institutions, other four variables were statistically significant towards success of ecotourism networks. The significant variables (number 1, 2, 5 and 6 in Table 2) have significant value of Chi square less than p-value (0.005).

Infrastructure support related challenges

With regard to second specific objective on infrastructure support, the findings (Table 3) indicated that, for success of TATO members in ecotourism, infrastructure support carries a high weight. Specifically, the findings revealed the need for having direct flights to Arusha especially from Western Europe (70%), all weather roads (55%), trail routing cycle path signs (40%), cultural heritage centers (50%), qualitable hotels and accommodation (40%) and reliable mobile phone networks (60%). Additionally, it has been revealed by 74% of the respondents that Ngorongoro conservations authority has a great impact on the success of tourism.

Further to that, the results of the tested second hypothesis show that all the five variables (number 1, 2, 4,5 and 6) are statistically significance (significant value < p 0.005). However, trail routing cycle path signs happened to be non-significant (p: 0.855 is higher than is 0.05).

Regulatory framework related challenges

The study findings on regulatory framework (Table 4) depicted the need for stakeholders to incorporate and consider the key issues for networks development, such as national tourism policy, laws, regulations, regulators ad promoters such as Tanzania Tourist Board (for over 62%). Contrary, more that 64% were not happy with the role of conservers, such as Ngorongoro Conservation Authority Agency in the success of ecotourism networks.

In addition to the above results on the degree of agreement, the hypothesis was also tested using Chi square value and the results (Table 4) show that the four variables (number 1, 2, 4,5 and 6 ) out of six are statistically significant (significant value < p 0.005). However, regulations and conservers happened to be non-significant due to higher value of significant than p, that is, 0.05.

Respondents’ characteristics

The male domination in ecotourism networks (72%) might be due to the nature of activities carried out and the difficulties encountered, particularly in the national parks and reserved areas as well as the need to stay out of home for long duration of time which challenged the majority of females and hence limit their involvement. The majority of respondents (84%) fall between 36-46 years (48% and between 26 to 35 years (36%). This spread of age group might be due to the fact that at age of 26 most of the people are physically strong, majority will be off schools and hence ready to work and take care of their families. Given below the age of 25, most respondents are still dependents on their parents or relatives and some are still in schools that is why we have only 2% representation. Furthermore, the group of respondents aged from 55 and above is few due to the oldness which limit active participation in ecotourism activities because physical strength start to decrease.

On education level, with 48% of respondents possessing university degree and 38% certificate of secondary education implied that over 80% are qualified enough to handle ecotourism related activities and communicate well with tourists. Additionally, with regard to 48% of the respondents possessing university education and have decided to engage into tour operations, this is might be attributed to the fact that there is a lot of graduate each year completing degree level of education but have no access to be employed by either the government institutions or private, hence decided to move to a large market on tour operations that have an opportunity to employ them simply because they can communicate well with tourists using English language. However, more effort is needed to attract other stakeholders with post graduate qualification who are very few due to minimum number of higher education institutions offering tourism related degrees particularly those specialized in tour operation.

With regard to the ownership structure, the findings that 68% of tours operating companies are owned by local investors; 10% fully owned by foreigners, and 10% of them are 50-50% local and foreigner’s ownership provide us with a smoke screen that there are large number of locally owned tour operation companies than the foreign owned. Thus, well supported ecotourism networks and other related activities have big opportunity of increasing employment in the region.

Furthermore, with respect to the duration engaged in tour operation business, the findings signify that the business of tour operations have a great impact on the financial earnings hence a group of people have engaged and do not want to move out of the business as far as the tourists continue coming and have a segment with tour companies, hotels and camps that receive a huge number of Tourists every month/day. Generally, there is a reasonable time from 4-10 years with 48% of all respondents engaging in tour operation business and itis a frog matching of a sign of continuing in business for years as most of those group are either from colleges, universities and followed by a big number of those from secondary school who have a range of 1-3 years in business. This group comprises of those who are not formalized and in Arusha they are commonly known as “fly catchers” or locally “Serengeti boys” who are found in street volunteering for catching tourists with a small bargaining price aiming to guide them to mostly Mt. Kilimanjaro or some national parks and game reserves.

Financial challenges

The first study objective aimed to assess financial related challenges to ecotourism networks. Specifically, it was intended to find out to what extent marketing capital, entrance fees to the attraction sites, license fees, support from a local financial institution, collateral for bank credits and exchange rate affects the success of tourism network in Tanzania. The general study findings revealed that financial support is very important for the success of ecotourism network in Tanzania. Ecotourism like any other sector cannot move without financial support because there are lots of activities that need money, for example improved working environment and services.

The findings revealed that key financial challenges are inadequate capital for marketing of tour activities affects the success and sustainability of tour operations, business, entrance fee to the attraction sites, and inadequate support from the existing support local financial institution. These financial challenges facing Tanzanian tour operators and TATO network are not unique as studies prove their existence somewhere else. For example, Thomas (2013) depicted that among the key barriers to community participation in tourism development in Ghana are the lack of government support (by 33%) and lack of funds (by 29%), thus the challenges of capital and credit facilities in tourism are like what is happening now in Tanzania due to its inadequate funding from the government. Because of this, Ghana is among the countries that are under performing in tourism sector as compared to its potentials. Moreover, study findings revealed that high entrance fee to the attraction site and high amount paid for the license really affect business operations for TATO members and hence the sustainability of the ecotourism business in general. From these findings, it is now the duty of the Tanzania government to look for more sources of income to support its operations so as to be able to keep the license fees and entrance fee as low as possible in order to attract more visitors.

Furthermore, the research findings show that about 64% of the total respondents agreed that local financial institution affects the success and sustainability of tourism business. Respondents revealed that most of the tour operators start businesses with very low capital and majority of them depend on the bank loans for starting the business. Findings revealed that collateral demand by financial institutions is a problem thus business financing becomes poor, consequently the business operates below standards. In lieu of that, some operators opted to join the foreigners for the sake of gaining experience, increase visibility as well as combining the capital for easy business operations.

Infrastructure support related challenges

Pertaining second specific objective on infrastructure support, the findings (Table 3) indicated that, for success of TATO members in ecotourism, infrastructure support must be given higher priority particularly ensuring that Tanzania is having direct flight from major tourists sources such as Western Europe, roads are reachable in all weather, there is clear trail routing cycle path signs, there is substantial number of cultural heritage centers, the quality and reliability of supporting services such as hotels, accommodation and mobile phone. On top of that, the findings shows that poor infrastructure support is one of the major obstacle towards the delivering of the services by the tour operators to customers not only in Tanzania but also in other African countries as also evidenced in Nkonoki (2012) thus immediate intervention is crucial.

These findings on the need for infrastructure support has also been supported by other authors worldwide for example in his study, Gakahu (1992) pointed out the importance of road network towards the success of tourism. He went on explaining that “what is needed basically is the continuous flow of visitors to the destination and to achieve this, there must be reliable roads that are not seasonal. It is the authors’ opinion that modern and international airport will host big planes which can bring tourists direct to our destinations. Thus, is the duty of government authority to see to it and find

better way of utilizing opportunity for the sake maximizing the national income and improve life of Tanzanians through employments creation via ecotourism.

Regulatory framework related challenges

Pertaining to the third specific objective on regulatory framework, the study intended to see the tourism laws, policies, regulations, regulators, conservers, etc. how does they lead to the success of Tourism in Tanzania. The study findings presented in Table 4 revealed the need for proper monitoring and regulation of the sector using machineries such as national tourism policy, laws, regulations, regulators ad promoters such as Tanzania Tourist Board.

Additionally, from the findings, it was revealed that although more that 64% of respondents were not happy with the role of conservers, such as Ngorongoro Conservation Authority Agency in the success of ecotourism networks, it was also established that Ngorongoro conservations Authority through its role and mandate has a great role to play towards the success of tourism. It is therefore the role of Ngorongoro Authority to put in place laws and regulations that enable tourism business to flourish. It has to be ensured that roads within are in good condition, entrance fees to the crater is affordable, reliable security is also available for fighting poachers and safeguarding tourists and make the area a safe place to visit.

This research was aimed at studying the challenges facing ecotourism network in Tanzania, using a case of TATO. The study ascertained the role of financial factors in the success and sustainability of ecotourism networks in Tanzania, evaluated the contribution of infrastructure support in success of ecotourism network and determined the effects of regulatory framework in the success of ecotourism network in Tanzania. The overall results have revealed a strong need for financial support, infrastructure and regulatory framework towards the success of ecotourism networks in Tanzania. The specific findings as far as financial support is concerned showed that adequate capital for marketing activities is highly needed by the Tanzania Association of Tour Operator. Moreover, the study findings revealed the need for the government of Tanzania to widen its source of income in order to reduce the taxes and license fees from tourists.In the case of the infrastructure support, findings show that, there is a lot do with the issues of infrastructure starting with direct international flights, all weather road meaning roads that are passable throughout the year, increasing feeder roads to avoid unnecessary long routes, trail cycle paths. Not only this, but also increasing the availability of modern cultural heritages as well as encouraging individuals, groups and the society at large to open these centers. Lastly was the issue of hotels and accommodation. Pertaining to the impact of the regulatory framework towards the success and sustainability of ecotourism network in Tanzania, all stakeholders in the sector must move in one direction, sing one song and aim to achieve common goal. Policy makers must formulate policies that will stimulate the pace of tourism in Tanzania, bring constructive changes and encourage most Tanzanians to own a business. Besides, Tanzania Tourist Board (TTB) and National Museums need to collaborate with other stakeholders like regulators, conserves, policy makers, research institutions and practitioners.It is expected that, these findings will contribute to the available literature and knowledge of the ecotourism sector, particularly on ecotourism networks, which is among the key source of employment in the study area of Arusha. Also, the tour operators, policy makers and other stakeholders will benefit from the research by increasing their knowledge on the existing challenges and setbacks as far as finance, infrastructure and regulatory framework are concerned and strategize further to work towards mitigating them.

Recommendations

The study has provided us with a theoretical framework for the role of financial support, contribution of infrastructure and the effect of the regulatory framework towards the success of ecotourism networks in Tanzania. Going through the study, many opportunities have been identified for further research. Because the research was conducted only in Arusha region and to some members of TATO, possibly results could be different if we would have interviewed a big sample, something which might reduce the degree of biasness. Other research should focus on TATO members living outside Arusha region so that to test the efficiency of TATO as one of ecotourism networks. The other area of study can be focused on tour operators who are not members of TATO to validate the results.

With regard to identified challenges, all key stake-holders under the coordination of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism must work together to address the identified challenges on finances, infrastructure support and regulatory framework so as to ensure sector’s effectiveness and efficiency. These issues need to be taken care of for the success of TATO and other ecotourism network as evidenced in Alejandro and Mara (2014) that ecotourism networks have generated bridging social capital, which has improved resource mobilization for infrastructure development, training and promotion, and generated new resources such as market information, logistics and certifications, increasing over time. All these issues if well addressed, will contribute towards the success of ecotourism network in Tanzania.

Limitation

During the research, some limitations have been encountered. Since the research was conducted during July and August, a so called peak season full of activities, most of the tour operators were not in their offices, so it was so difficult to get the required information at the right time, for this case, this research was time consuming and used high margin of error.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Alejandro CHD, Mara RB (2014). Networks in strengthening community-based ecotourism in the Sierra Norte of Oaxaca, Mexico. Int. J. Adv. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2(3):24-32.

|

|

|

|

Anderson W (2009). Promoting Ecotourism through Network: Case Studies in the Balearic Islands. J. Ecotour. 8(1):51-69.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Anderson W (2010). Determinants of all-inclusive travel expenditure. Tour. Rev. 65(3):4-15.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Anderson W, Juma S (2011). Linkages at tourism destinations: challenges in Zanzibar. ARA J. Tour. Res. 3 (1):27-41.

|

|

|

|

Buckley R (2008). Environmental Impacts of Ecotourism. CABI Publishing, British Library, London, UK.

|

|

|

|

Busan D (2004). Challenges Tour Operators in South Africa faces.

|

|

|

|

Carlson L (2009). Tanzania tourism and travel news

|

|

|

|

Ceballos-Lascurain Architect (1983). Definition adopted by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) and World Tourism Organization (WTO) in 1993.

|

|

|

|

Citizens Newspaper (2011). Global Tourism board supports Tanzania projects. Tourism Development in Perspective.

|

|

|

|

Davidson R (1993). Tourism. Longman: UK, PB, ISBN 0582288541 stlg14.99

|

|

|

|

Donaldson T, Preston LE (1995). The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. In: Academy of Management Review. 20:65-91.

|

|

|

|

Dougherty M, Green GP (2011). Local food tourism networks and word of mouth. J. Extension. 49(2):5.

View

|

|

|

|

Duffy R (2008). .Neoliberalising Nature: global networks and ecotourism development in Madagascar. J. Sust. Tour. 16(3):327-345.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Fennel D (2001). "A content Analysis of Ecotourism Definitions". Current Issues Tour. 4:403-421.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Gakahu CG (1992). Tourist attitudes and use impacts in Masai Mara National Reserve. Wildlife Conservation Society, New York.

|

|

|

|

Haralson J (2012). Ecotourism: A Global Perspective, Digital Media Journalist.

|

|

|

|

Honey M (2008). Ecotourism and Sustainable Development -Who Owns Paradise?405 p. Island Press, Washington D.C.

|

|

|

|

Mgwila DE (2010). Inventory study on cultural Tourism Initiatives in West Serengeti.

|

|

|

|

Miaoulis G, Michener RD (1976). An Introduction to Sampling. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

|

|

|

|

Miller (2007). Global Ecotourism Conference. Oslo Norway, May 14-18.

|

|

|

|

Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism (1999). National Tourism Policy. Government Printer, Dar es Salaam.

|

|

|

|

Morrison A, Lynch P, Johns N (2004). International tourism networks. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manage. 16(3):197-202.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Nkonoki S (2012). Challenges of Tour Operators Case: Dar-es-Salaam,

|

|

|

|

Pasape L, Anderson W, Lindi G (2013). Towards sustainable ecotourism through stakeholder collaborations in Tanzania. J. Tour. Res. Hosp. 2(1).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Piekkola E (2013). Ecotourism potential of Amani Nature Reserve, Tanzania. Unpublished Master's Thesis University of Helsinki.

View

|

|

|

|

Science Daily (2012). Infrustructure.

View

|

|

|

|

SNV: Netherlands Development Organization (2010). Corporate annual report.

View

|

|

|

|

Tanzania Association of Tour Operators (2015). About us.

View

|

|

|

|

Tanzania Tourist Board (2009). Tourism Atractions.

|

|

|

|

Thomas Y (2013). Ecotourism development in Ghana: Acase of selected communities in the Brong- Ahafo Region. J. Hospit. Manage. Tour. 4(3):69-79.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Thome WH (2015). Tanzania's best kept tourism secret. African Travel magazine.

View

|

|

|

|

Weaver D (1998). Ecotourism in the less developed world. Wallingford: CABI.

|

|

|

|

Weaver D (2008). Ecotourism. Australia: John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd.

|