Environmental advocacy on American television draws upon utterly exhausted stereotypes, which have become part of a popular discourse. This article serves as an installment in an ongoing project at York University. It analyzes the ideological framing and discursive construction of environmental advocacy, suggesting that such portrayals perpetuate cognitive injustice through the perpetuation of stigmatizing discourses. The power of these discourses reduces the credibility of environmental campaigns, situating discourse in a matrix of power which encourages a culture based on perpetual growth and industrialization, consumption, and anthropocentrism.

Critical discourse analysis

The theoretical framework utilized used in this study draws heavily upon the works of Michel Foucault (1980) and Norman Fairclough (1989, 1992, 1997, 1995, 2000, 2001). The discipline of discourse analysis recognizes that discourses are value-laden and are articulated in hegemonic structures. Discourses, then, are comprised of multiple and conflicting readings which lead to the construction of social hierarchies, projecting a particular perception of social life (Shuter and and Turner, 1997). Foucault’s exposition of discourse and power lends credence to the field of discourse analysis. If as Foucault (1970) argues, discourse is social practice, which includes not just dialogue but activity and systems of behaviour, we must explore the power of discourse - its capacity to create myriad social realities, creating and sustaining unequal social orders. In a seminal piece entitled Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language, Fairclough (1995) sketches his (macro/micro) explanatory framework. ‘Micro’ events encompass common verbal events, whereas ‘macro’ structures serve as the conditions for and products of ‘micro’ events. The author highlights the crucial relationship between the ‘micro’ and ‘macro’ wherein ‘micro’ verbal interactions and events cannot be interpreted as simply ‘local’ discursive events because they contribute to ‘macro’ structures, and vice versa. The process of domination, then, is captured in the intricate relationship between ‘macro’ and ‘micro’ modes of analyses of discursive events. Language, for example, is not powerful on its own; rather, it gains power through the manner in which it is deployed by the powerful. Teun A. van Dijk (2003), for example, contends that in order to study the abuse of power, it behooves researchers to examine how powerful groups and institutions manage to project their values and beliefs in public discourse.

The act of producing and projecting these values via discourse also encompasses their legitimation and transformation into taken-for-granted assumptions in the public domain. In a related vein, theories of the hierarchical structuring of information and the theory of tonalization posit that language presents information in hierarchical order via text (macro level) and utterances (micro level) (Lavandera, 2014; Pardo, 2011). Other theories and practices used by scholars in the analysis of textual practice include: theories of verbal processes which maintain that speakers discursively construct themselves, and others, using various discursive processes associated with more or less agentive roles (Halliday and and Mathiessen, 2004); theories and models of analysis which address the explicit and implicit argumentation in texts (Pardo, 2011; Molina, 2012; Toulmin, 1958); theories of conceptual metaphor, which assist in the classification of metaphors used by speakers when conceptualizing the world (Lakoff and and Johnson, 2003);

multimodal analyses of non-textual elements of discursive practices (Kaltenbacher, 2007; Kress and and Van Leeuwen, 1996); and, of course, analyses of the audio-visual context of texts, such as the use of camera angles, visual effects, music and non-diegetic sound (D’Angelo, 2007; D’Angelo et al., 2009).

Frame analysis

No undertaking of CDA is complete without reference to framing. Originating within the disciplines of sociology and psychology (Scheufele and and Tewsbury, 2007), scholars like Goffman (1974) have expanded on the practice of framing, arguing that frames are configurations used to categorize and organize human experience. Goffman (1974:p.10) explains that human experience entails:

“Definitions of a situation built up in accordance with the principles of organization which govern events - at least social ones - and our subjective involvement in them; frame is the word I use to refer to such as these basic elements as I am able to identify. That is my definition of a frame”.

The ‘schemata of interpretation’, according to Goffman, enables one to engage in the process of ‘frame analysis’ - that is, the act of uncovering meaningful aspects of seemingly meaningless scenes (Kendall, 2005). This article operates on the basis that frames influence interpretations of reality and follows recent applications of framing within cognitive, constructivist and critical perspectives (Reese, 2007). It is the critical perspective, however, which interests me for the purposes of this project, because this perspective sees frames as mechanisms of hegemonic control employed by the powerful. Robert Entman (1993) has also contributed to the conversation on framing, defining the process as the representation of certain aspects of a perceived reality. This representation, therefore, promotes a “particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation and/or treatment recommendation” (Entman 1993, p. 52). Such an explanation is useful when understanding how the media influences public attitudes on myriad political issues (Chong and and Druckman, 2007; Clawson and and Waltenburg, 2003). Frame analysis, like CDA, therefore, is of paramount importance when investigating how discursive practices are situated in matrices of hegemonic power.

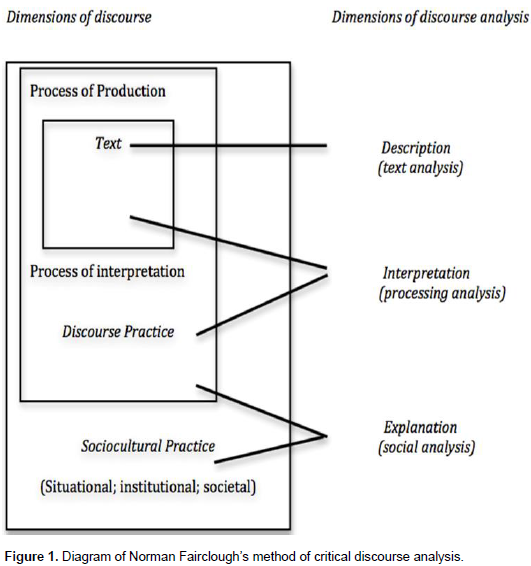

Discourse analysis can either be qualitative or quantitative; however, this article will focus exclusively on a qualitative approach. An interdisciplinary endeavour, CDA encourages a dialogue between those interested in linguistic and semiotic analysis and those preoccupied with formulating theories of social change. With this in mind, CDA promotes interdisciplinary approaches to conducting research. Consider, for example, Fairclough’s ‘three-dimensional’ framework for conducting discourse analysis. This framework draws upon various levels of analysis - most of which capture the phonological, grammatical and lexical components of discourses (Fairclough, 1995). CDA also uses theories of language and grammar - both of which highlight the ideational, interpersonal and textual functions of language. According to Fairclough, CDA can be consolidated as a ‘three-dimensional’ framework, encouraging three separate modes of analysis: analysis of spoken or written language texts; analysis of discourse practice; and analysis of discursive events as social practice. Fairclough (1995: 97) explains,

“Discourse, and any specific instance of discursive practice, is seen as simultaneously (i) a language text, spoken or written, (ii) discourse practice (text production and text interpretation), (iii) sociocultural practice at a number of levels; in the immediate situation, in the wider institution or organization, and at a societal level”.

The methodological guidelines for conducting CDA are accompanied by the exercise of describing the text; interpreting the relationship between both the productive and interpretive discursive processes of a text; and explaining the complex relationship between discursive processes and social processes. The emphasis upon description, interpretation and explanation has served as the foundation of CDA. This analytical framework engages in linguistic and intertextual analysis, capturing the complex, contradictory sociocultural processes of discursive events. Consider, for a moment, Fairclough’s (1995) diagram depicting the application of CDA in critical research (Figure 1). Now that the basic components of CDA have been reviewed, let us now turn to the practice of sorting and categorizing data. Discourse analysts refer to this procedure as coding (Potter and Wetherell, 1987; Fielding, 1993; Seale, 1999; Silverman, 1998; Taylor, 2001). Coding enables the translation of robust data into categories. Once these categories are formulated and the data has been sorted, analysts begin to search for prominent patterns in language use. Coding also enables researchers to formulate concepts for organizing data such as interpretative repertoires, ideological dilemmas and subject positions - all of which are useful when conducting CDA (Edley, 2001).

Study approach

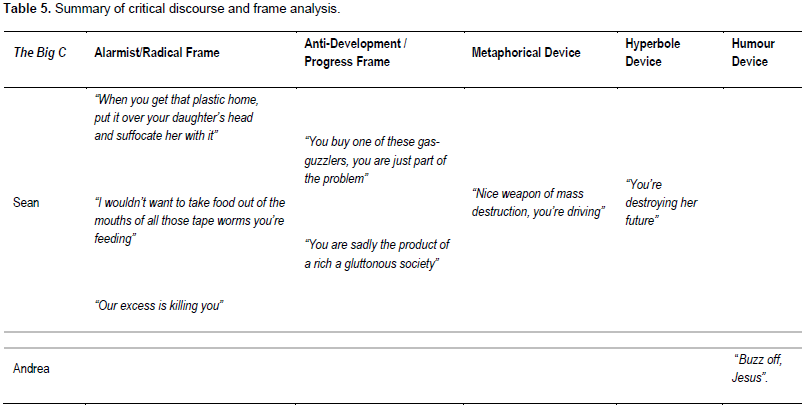

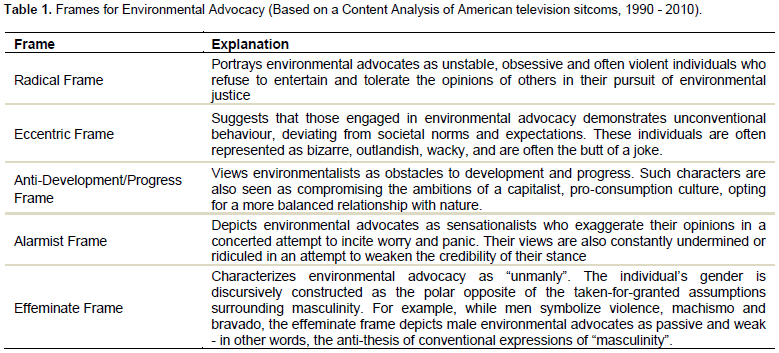

The corpus for this research project was culled from different Internet sites: YouTube, online television channels and Fandom sites. It comprises excerpts and fragments from a multitude of different television genres. Basic and advanced searches were conducted on Google and YouTube using key concepts such as “environmental advocacy on television sitcoms” or “examples of environmentalism on television shows sitcoms”. For the sake of brevity, the analysis here will be confined to four examples: Saved By The Bell, In Living Colour, Da Ali G Show and The Big C. The corpus features television shows spanning 20 years: the 1990 - – 2010. Using qualitative content analysis, this study reviewed each episode of the sitcoms, recording the discourses used to characterize environ-mental advocacy. Coding the frames was an imaginative endeavour, as each episode was re-watched, tables were formulated and coding sheets were used to capture salient frames. Note, in some examples, a single example featured multiple frames, adding to the richness of the linguistic strategies and discursive representations of environmentalism. The frames were seemingly diverse, yet unified by overarching motifs - most of which cast negative stereotypes on characters who demonstrated a sense of advocacy on behalf of the environment. Most importantly, the identification of these frames, in conjunction with the concepts of interpretative repertoires, ideological dilemmas and subject positions, allowed theorization of the perpetuation of cognitive injustice via popular discourses. Table 1 features the various frames identified during the critical analysis of the discourses in the sample of television shows:

Discourse and frame analysis

Example 1. Saved by the Bell, Season 3, Episode 11: “Pipe Dreams” (aired 1991)

The beloved teens from NBCs incredibly popular Saved by the Bell discover that oil is beneath their school’s football field. This causes Jessie Spano, an avid feminist and environmentalist, to voice her opinions on the deleterious effects of drilling. She, however, is met with much skepticism from the rest of the characters. Let us begin with the opening act: the lead character, Zack Morris, enters his biology class holding a duck, which appears injured. He proceeds to explain that while playing baseball, he accidentally hit the creature. Jessie remarks: “Hit by a ball: typical. That’s what happens when man encroaches upon animals’ domain”, to which Zack replies “Jesse, it was an accident; not a case for L.A. Law”. From the beginning of the episode, Jessie is framed as an alarmist who displays a tendency for exaggeration. Her observations regarding humankind’s encroachment upon the domain of the animals, albeit thoughtful and astute, are immediately undermined by Zack’s humourous and sarcastic comment about involving L.A. Law, a clear attempt to poke fun of Jessie. Consider, for example, scholar Janet Holmes’ (2000) work on the role humour plays in discourse. The author posits that humour functions in unequal encounters between agents, serving as a strategy for one party to maintain a position of power via discourse. Zack’s use of humour throughout the entire episode maintains his position of superiority over Jessie, reminding viewers that her advocacy for the environment is futile.

In a subsequent act, the characters are sitting in the local campus hangout, The Max, and Slater enters the establishment in a frenzy, explaining that the school has discovered oil beneath the football field: “Guys, you’ll never guess what happened when they were putting up the new goal post. They were drilling and they must have hit a pipeline; there’s oil squirting out”. Jessie immediately quips: “oh, you see. That’s what happens man alters the natural order of the environment”, to which Slater responds, “Hey chill out, mama. It was a chick digging the hole”. Similar to her previous interaction with Zack regarding the relationship humans have with nature, this exchange with Slater merely utilizes uses humour, again, to re-frame Jessie as a neurotic alarmist who over-theorizes ecological destruction. Her advocacy is undermined by Slater’s jab that “it was a chick digging the hole”. His use of sexist language aims to depoliticize Jessie’s comments, diverting attention away from the issue really at hand - that is, the irreversible transformation of the environment. Both Zack and Slater’s comments, then, can be interpreted as discursive devices which weaken the credibility of Jessie’s opinions and knowledge about the fragility of the environment. The alarmist frame is, again, presented in a later act when Jessie convinces two other students to chain themselves together in the school hallway chanting, “Stop the drilling, stop the oil!” Zack sees this act of protestation and yells, “What’re you guys doing? Jessie, you’re being an alarmist…You’re making a fool of yourself”, to which Jessie replies, “Protesting for what we believe”. Again, Zack’s use of the words “alarmist” and “fool” merely reduce the credibility of Jessie’s activist energy. It is though there is something foolish about her passion for ecological justice.

As previously mentioned in this article, the practice of coding revealed the presence of multiple frames in these analyses. In conjunction with the alarmist frame, examples of the radical and anti-development/progress frame were found. With respect to the former, upon discovering that oil is beneath the school’s football field, the students descend into a fantasy sequence where they envision how their lives might be enhanced by their newly acquired wealth. While the other students imagine becoming wealthy entrepreneurs, Jessie imagines she possesses enough wealth to hunt down environmental polluters. In the fantasy sequences, for instance, she is seen speaking on two telephones simultaneously while her butler asks, “Are you comfortable, Miss Jesse?”, to which Jessie responds, “Quiet. I’m tracking down environmental polluters. I’m gonna tie their noses to exhaust pipes until they go solar”. The radical frame is captured in her pursuit of environmental justice. Justice, in her eyes, entails the act of tying these polluters’ noses to exhaust pipes. This undergirds the stereotype in mainstream media that environmental activists are violent, irrational and radical ecologists who will do anything to achieve their aims. In a related vein, the anti-development/progress frame is captured in Jessie’s exchanges with various characters in this episode. For example, when Dan Grayson, a representative from Callstar Oil, speaks to the students about his company’s extraction methodologies, Jessie inquires: “Why do we need more oil? I mean why not focus on alternative sources of energy like the sun”.

The representative laughs and replies, “Well, because the sun’s our competitor, young lady, and we are in the oil business”. Dan’s use of humour, again, functions in clearly delineated power relations between himself and Jessie (Holmes, 2000). What is more, Jessie’s suggestion is clearly interpreted as a threat to the economic growth and the progress of Callstar Oil, and the representative’s claims that the sun is a competitor reflects the capitalist ethos of market competition. The anti-development/progress frame is captured in another exchange when the students hear the extraction company drilling for oil. One of the students asks what the boisterous noise is and Jessie replies, “It’s the oil company disturbing our environment”. Zack shakes his head and replies, “Oh no it’s not. It’s just a two-tonne woodpecker. Can’t make an omelette without breaking some eggs”. Discourse analysts take heed of the use of metaphorical devices (Hart, 2008) because such structures contain implicit ideologies, exercising tremendous power over those consuming the texts (Fairclough, 2001). Zack’s metaphor of breaking eggs to make an omelette, therefore, can be interpreted as a metaphor for progress and development, and, of course, the concomitant environmental risks and externalities. Jessie’s comments, therefore, are construed as anti-development/progress.

This was observed again in a subsequent act when oil accidentally spills into the pond adjacent to the school, killing a number of animals, including a duck named Becky. When the students confront their principle, Mr. Belding, about stopping the drilling, he responds: “I feel as bad as you do. I loved going down to the pond and feeding Becky; accidents happen”, to which Jessie laments, “Accidents happen a lot with oil companies then they just slip out of being responsible for them”. Mr. Belding then explains, “Jessie, it’s not simple. With yu7lprogress there’s often a price to pay. People died in the space programme. Does that mean we should stop exploring the universe?” Mr. Belding’s comparison of drilling oil to space exploration captures the essence of progress and development: that there will always be a price to pay but we should continue apace under the ideology of progress. Jessie’s reflection on how these companies evade penalties and punishment for their deleterious activities presents her as an enemy to progress and development (Table

Example 2. In Living Colour, Season 3, Episode 7: “Act Up! Guy in the Park” (aired 1991)

In Living Colour was a very successful American sketch comedy series from the 1990s. One particular sketch entitled “Act Up! Guy in the Park” warrants a critical analysis of the series’ ideological message regarding environmental advocacy. In this sketch, Jim Carrey portrays an utterly eccentric character whose prerogative is to ruin families’ outing at a local park. Multiple frames inhere in this sketch, but it is the portrayal of Carrey’s activism which garners attention. Reflecting on Marshall McLuhan’s (1964) phrase “the medium is the message”, we begin to see that mainstream media not only denigrates the message of environmentalists, but also their medium (in this case, facets of their identity). The scene opens with an environmentalist, who remains nameless and is referred to in the series simply as Guy, entering a park and blowing a whistle. He is wearing a tie-dyed T-shirt and is holding a placard which reads “Save the Planet”, while screaming at the top of his lungs: “Listen up, people. I am here and I wanna help. This is our planet; can I get a hooray?” The crowd at the park ignores Guy and he descends into a frenzy yelling, “What am I, invisible? Doesn’t anyone care? Listen to me”. The effeminate and eccentric frames intersect in this sketch because Guy speaks with a lisp and in a very flamboyant manner. While this portrayal of environmental advocacy attempts to poke fun at activists and protesters, it also draws upon negative stereotypes, creating a tacit suggestion that his gender and sexuality correlate with his advocacy for the environment.

As the sketch proceeds, Guy approaches a couple ordering hotdogs from a street vendor and interjects: “You need to stop this insanity. What do you think you’re doing here?”, to which the vendor responds, “I’m trying to make a living here”. Guy stomps around and yells “And the planet is dying!” He grabs a nearby plant and looks at his wrist, stating, “I can’t get a pulse”. Guy proceeds with a monologue:

“There are 50,000 hotdog cows in Kansas alone. When

those cows break wind, not only is it stinky, it’s cutting a

hole in the ozone. Think of those hotdogs as one cubic foot

of cow gas”.

The couple looks disgusted by Guy’s remarks and they return their orders and leave the vendor. Guy tries to console the vendor, patting his back and remarking, “See, we can make a difference”. The vendor replies, “I’ll make a difference on your face, if you don’t get out of here” and Guy quips snidely, “The truth hurts, doesn’t it,

captain carnivore!”

The eccentric and radical frame inhere in Guy’s monologue here, especially his use of hyperbolic rhetoric. Scholars such as Burgers et al. (2016, p. 166) comment on the use of hyperbole in discourse, defining it as “an expression that is more extreme than justified given its ontological referent”. The trope features elements such as exaggeration (Carston and Wearing, 2015), over-statement (Colston and Keller, 1998), extremity (Norrick, 2004) and/or excess (CanoCano, 2009). For example, Guy’s comments about the consumption of hotdogs constituting a form of “insanity” and that the “planet is dying” serve as rhetorical devices to persuade the customers that they must cease eating animal by-product, lest they destroy the planet. The exchange between Guy and the vendor serves as a microcosm for the debate between those who consume animal by-product and those who do not. The latter are frequently portrayed as radical and eccentric animal rights activists, and are usually perceived as a nuisance and annoyance by mainstream society because of their convictions. In fact, Guy’s behaviour causes the vendor to lose money, as the customers change their minds about ordering the hotdogs, hindering his ability to “make a living”. The vendor’s response speaks to a larger issue: that environmental advocacy hurts small businesses trying to make ends meet due to their radical and eccentric tactics to spread their beliefs.

In the following act, Guy flamboyantly marches off to a family that is celebrating a birthday party. He hears the mother explain to the children, “Okay little Ricky, now break the piñata”. He runs over the family and screams, “No parents, don’t do it! Don’t teach the children how to kill. This is genocide”. The mother looks at him in disbelief and utters, “This is a birthday party, would you get lost?” Guy tilts his head back and yammers, “Smoke screen, smoke screen so the truth cannot be seen”. He continues, “Listen kids, first you hit a piñata. Next, you’re clubbing baby seals. This is real, children. These are the killing fields. The piñatas are piling up. Are you with me?” Guy puts his arms around the children, trying to persuade them to join his cause but they laugh at him. Consumed with rage, he yells “The hell with you, then”. He reaches for the piñata, attempting to dismantle it from the tree and one of the fathers yell, “Hey, hey, hey man. If you don’t get out of here, I will call the police and I’ll whip your ass”. Guy stares at the irate parent in disbelief and inquires, “You’ve been eating hamburger, haven’t you? I swear I could just strangle you”. Again, the radical frame emerges in the exchange between Guy and the children. For example, his accusation that child’s play is a form of genocide is completely baseless and mere exaggeration (Burgers et al., 2016).

What is more, his attempts to imply causation between breaking a piñata and “clubbing baby seals” or dubbing the playground as “the killing fields” are examples of his radical logic. Particularly, this term “killing fields” operates as a metaphorical structure (Hart, 2008), which reinforces Guy’s radicalism in the context of this exchange with the children. We see this again when Guy threatens the father by saying “I swear I could just strangle you”, undergirding the construction of environmental advocates as volatile and violent people willing to do anything in order to get their message heard. In the following scene, Guy is walking in the park and inadvertently catches a football. He looks around and yells, “Whose is this?” A young man approaches him and asks Guy to return the ball. Guy stares at him and inquiries, “Do you know what’s in this thing?”, to which the young man replies, “Air”. Guy retorts, “Of course there’s air, lots of air that we could be breathing. Free the air!” Guy frantically uses his teeth to tear a hole in the football, deflating it as he yells, “Go little air, go!” The young man wrestles the ball away from Guy as he continues to scream, “Fly away, fly away”. The sketch proceeds to its conclusion when Guy witnesses a young woman cleaning up after her dog. Guy runs over to her and snidely asks:

“Oh you poor ignoramus, what are you doing?”

“I’m taking care of my dog’s business”.

“You can’t put his doody in a plastic bag, it’s not biodegradable”,

“All I want to do is get rid of it”.

“No! Save the feces to feed the planet. You people make me so exasperated. I could just rub your nose in it, but it would be such as waste”.

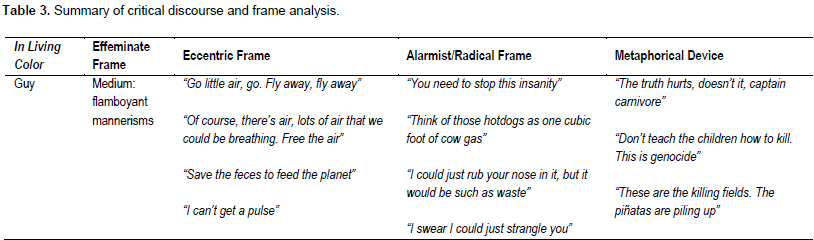

Both eccentric and radical frames inhere in the interactions with the football player and dog walker. For instance, Guy’s attempt to free the air inside of the football demonstrates how eccentric his beliefs are as an environmentalist: he truly believes that the air held captive in the football should be freed in order to save the planet. He takes his eccentric behaviour further when he anthropomorphizes the air by yelling at it: “Go little air, go” and “Fly away, fly away”. The radical frame, on the other hand, is captured in Guy’s exchange with the dog walker. He rudely refers to her as a “poor ignoramus”, then threatens to rub her nose in dog feces when she refuses to leave the feces in the grass as fertilizer (Table 3).

Example 3. Da Ali G Show, Season 3, Episode 4: “Realize: Ali G’s Guide to Da Environment” (aired 2004)

In the episode “Realize: Ali G’s Guide to da Environment”, comedic and unorthodox journalist Ali G interviews tree protestors Shunka, Huckleberry, Whisper and Grasshopper, members of Earth First!, an environmental advocacy group from the United States. From the very beginning of the interview, Ali G pokes fun at the members’ beliefs, but a closer discursive analysis reveals the use of humour and certain frames, which produce stigmatizing discourses about environmental advocacy, reinforcing his superiority over the activists. Consider, for example, an exchange between Ali G and Huckleberry, who is hanging from an old redwood tree:

“What are things like this tree used for?”

Mainly luxury items, you’d see a lot of redwood hot tubs; a lot of redwood decks”,

“ “So you’re telling me that this tree wouldn’t prefer being a hot tub with a couple of fly honeys totally, ya know, no clothes on, rather than having you in it?”

Ali G employs humour as a discursive device (Holmes, 2000) in order to maintain a position of power over the protestors. Humour, along with the eccentric frame, represents Huckleberry as an outlandish and wacky tree protester, whose protection of the redwood trees is both futile and absurd because the tree, allegedly personified, would rather serve as a hot tub for beautiful, naked women. The eccentric frame is utilized used again when Ali G asks Shunka if he has a message for the camera, to which Shunka responds, “Rise up and rebel with non-violence with our actions and our words, thoughts and songs”. Ali G proceeds to ask what songs have the tree protesters written and Shunka sings one of their compositions entitled “Gentle Warrior” in a cappella: “Gentle warrior, with a heart like gold and a rainbow in your eyes, brave companion”. At the end of Shunka’s performance, Ali G looks into the camera and states: “No offence, but that song, in my opinion, is a bit crap”. Ali G’s insensitive comments serve to reduce the credibility of Shunka’s thoughtful message regarding non-violence, framing him as a passive and eccentric activist whose message, and medium, are utter folly in the pursuit of ecological justice–in so many words, “crap”.

In the next act, Ali G and Shunka are facing the camera and Ali G states:

““All you out there, and I’m speaking for me and my friend here, go out there and publicize this thing. Talk to your friends, make something that makes a difference: burn a car, whatever, mash people up, but let them know you are doing it for this cause, so we can get publicity”. Shunka shakes his head in disapproval. He immediately replies, “Stay non-violent, and we don’t do property destruction”. Ali G responds by asking: “But yo, wouldn’t it be more better for your cause if people are smashing things up, saying yo, I’m doing this for the tree people”, to which Shunka resoundingly says “no, no”. In the next shot, Ali G is standing beside Grasshopper and poses the question,

“Wouldn’t it be good if it weren’t just smelly hippies who

was doing it, but it was also like normal people?”

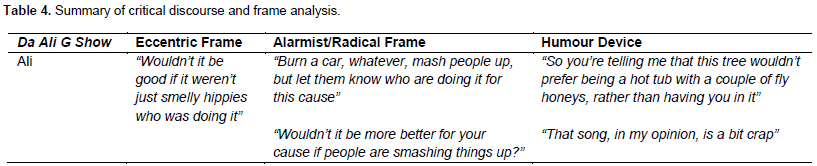

Grasshopper shakes his head and replies, “If it was everybody doing it, then they’d find a way to demonize the regular people”. This exchange between Ali G and the tree protestors clearly reveals the intersection of both the eccentric and radical frame, but also the use of a systematic ‘othering’ and negative stereotyping (Teo, 2000) of environmentalists. For instance, Ali G’s rhetorical, and contrastive, use of terms such as “smelly hippies” and “normal people ” frames the members of Earth First! as somehow abnormal, reinforcing disparaging and demonizing stereotypes about environmental activists and their campaign. Finally, the radical frame is employed when Ali G attempts to produce propaganda about the activities the tree protesters engage in. He manipulates the interviewees by attempting to impose his own view of what Earth First! embodies. The references to “burn a car” or “mash people up” clearly demonstrate both the construction, and imposition, of the radical frame unto environmental advocates (Table 4).

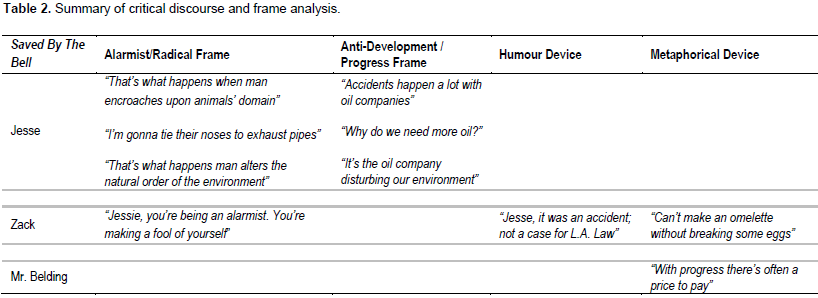

Example 4. The Big C, Season 1, Episode 1 and 2: “Pilot” and “Summer Time” (aired 2010)

Showtime’s The Big C aired in 2010, running for only 4 seasons. Yet, the show projects a very provocative portrayal of environmental advocacy through the discursive construction of one of the main characters: Sean Tolkey. Sean is a middle-aged yuppie who is very concerned about the fate of the planet and tries to educate the masses on the perils of anthropocentric activities. For example, in the pilot, Sean is seen protesting outside of a department store about the danger of customers using plastic bags. He approaches a young family with a daughter and inquires, “Excuse me, you guys have a minute to help save the planet?”, to which the mother responds, “No”. Sean retorts in a very crass manner: “When you get that plastic home, put it over your daughter’s head and suffocate her with it. You’re destroying her future”. In the subsequent act, he is dining in a fast food restaurant with his sister, Cathy, but he refuses to buy food, opting instead to eat other customers’ leftovers. Cathy, humiliated, tells her brother that she would have bought him a meal, but Sean explains,

“We throw a tonne of food away in this country every day, and not in figurative time, in actual time. Besides, I wouldn’t want to take food out of the mouths of all those tape worms you’re feeding”. In the final act of the first episode, Sean returns to the department store, ties a noose made of plastic bags around his neck and pretends that he is hanging from a tree. Again, discursive elements such as exaggeration (Carston and Wearing, 2015), overstatement (Colston and Keller, 1998), and extremity (Norrick, 2004) operate in conjunction with the alarmist and radical frames. Consider, for example, Sean’s aforementioned exchange with the family about their use of plastic bags. His alarmist and radical mindset likens the purchase of a plastic bag with the extreme act of putting it over a child’s head and “suffocating” her with it, all in the name of the preservation of the environment. Sean’s behaviour constitutes a very alarmist and radical stance on the issue of the proliferation of plastic bags in grocery and department stores. The eccentric frame, on the other hand, is captured in the subsequent act when he is dining with Cathy. Sean refuses to support the fast food industry by purchasing their food items, but will eat the scraps belonging to other customers in an effort to reduce his ecological footprint. His desire to reduce the waste, albeit thoughtful and admirable, is met with utter disgust from his sister who is embarrassed by his behaviour in the restaurant, and his subtle commentary on the ingestion of animal by product. In the second episode, Sean is protesting, yet again, but this time he is outside of a car dealership. The act opens with him standing shirtless in the parking lot, speaking through a megaphone:

“It’s hot today, isn’t it? It’s actually three degrees hotter

today in Minneapolis than it was one year ago. You know

why? Global warming, baby! You buy one of these

gas-guzzlers, you are just part of the problem”.

Cathy drives up to him in her SUV and he is aghast, stating: “Nice weapon of mass destruction, you’re driving”. Cathy tries to convince Sean to put on a shirt, lest he embarrasses himself, but Sean refuses. She then informs him that she is donating some of her son’s clothing and offers some trousers to Sean. He sifts through the folded clothing then decides on a pair of shorts, but only after removing his pants in the parking lot. The camera focuses out so viewers get a clear shot of his naked backside. Cathy, mortified by her brother’s actions, turns her head in dismay while he changes into his newly acquired clothing. She then recognizes one of her students, Andrea, walking by the dealership. In the previous episode, Cathy imparts some advice to Andrea about losing weight, suggesting that Andrea remove junk food from her diet, whilst increasing her levels of physical activity. When Sean meets Andrea, he states: “While I generally like your look, you are sadly the product of a rich gluttonous society. Our excess is killing you”, to which Andrea responds, “Buzz off, Jesus”.

The second episode features an intersection of frames- namely, the alarmist, eccentric and anti-development/ progress. Let us begin with Sean’s informative lecture on global warming. He is seen shirtless in a parking lot, chastising customers through a megaphone, educating them on the dangers of global warming. Such alarmist behaviour is paired with his comment about consumers being “part of the problem” through their purchasing power. The sub-text of his discourse speaks to a larger issue, however. Sean’s monologue can be construed as anti-consumerist/capitalist in the sense that he is trying to dissuade people from buying these vehicles. His sentiments, then, are anti-development/progress because he is hindering the business of the dealership in his alarmist and radical act of protestation. The use of the metaphorical structure “weapon of mass destruction”, is both deliberate and calculated. Sean’s rhetoric merely underscores his views about consumerism, capitalism and development. He takes a pillar of the “American Dream” (a brand new vehicle, in this case) and refers to it as a “weapon of mass destruction”. That metaphor conjures up images of myriad life-threatening devices, reminding people about the implications of their consumption practices. Finally, his observation about Andrea, albeit astute, is, frankly, mean-spirited and offensive. The radical frame, again, is aligned with the anti-development/progress frame when he observes that Andrea’s perceived struggles with losing weight is “the product of a rich gluttonous society”. Sean views gluttony as a concomitant of consumerism, capitalism, development and affluence. His radical observation is met, then, with hostility from Andrea who refers to him as “Jesus”, but in the pejorative sense of the name, meaning his attempt to spread salvation is not only futile but unwelcome (Table 5).