Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

This study sought to establish the adherence to professional and ethical principles of reporting insecurity matters by journalists in Kenya. Kenya has continuously grappled with national security issues since the 1998 US embassy bomb attack. Terrorist attacks have become a frequent and major cause of insecurity. This has been aggravated by the frequent sectarian, religious and ethnic violence in various parts of the country. Notably, some of the insecurity situations in Kenya are a result of conflict situations. From the findings of this study, it was evident that the media seldom used expert opinion in their news programmes on matters of insecurity. It was also clear that the largest percentage of insecurity as reported by the media resulted from terrorism activities followed by security operations by the state security machinery. From the findings of this study, some of the articles had sensational and unjustified news aspects in the story. However, the headlines of stories relating to insecurity were largely descriptive and informative and did not seek to incite or provoke any community to violence or vengeance. While the media did not perform poorly in terms of conflict sensitive reporting, some of the words that were used by some newspaper articles and TV clips were in violation of stipulated tenets of conflict sensitive reporting. The study recommends the separation of facts and opinion when reporting insecurity should be clearly upheld. Journalists should choose their words very carefully when reporting on conflict instigated insecurity matters in their stories. The media have a responsibility for contextualized, meaningful reporting where news programs have adequate background information on historical, cultural and even political perspectives of conflicts causing insecurity. This allows audiences to make informed decisions

Key words: Ethics, reporting, security, terrorism.

INTRODUCTION

Reporting security matters is sometimes a complex and tedious activity that endangers the life of journalists most of the times. The desire to attain “scoop” story status, newsroom pressures and the swiftness of some of the attacks are just but some of the complexities ad dynamics that journalists face on a daily basis in their coverage of security. That said, the Kenyan news media plays a significant role in shaping and interpreting public perception of national security policies and their legality and therefore have a great responsibility to carry out their functions with the highest possible degree of professionalism and adherence to code of conduct.

State security operations are often considered as tactful, reactive and sometimes secretive measures to mitigate any form of insecurity that a country may face. In the execution of its strategies, the states security machinery has been previously known to restrict access to information or seek to co-opt journalists, while the media may risk internalizing official perspectives on perceived threats to national security. Reliance on and privileging of official statements and a lack of expertise on security issues have been known to undermine the media’s ability to act as a watchdog. To play an effective role in overseeing the security sector, journalists must have a degree of distance from government and protection from intimidation and threats.

The Kenyan situation presents a complex situation where the media has often failed to undertake factual and comprehensive coverage of security matters. The focus on the sensational and dramatic elements security in news programmes has made audience decry the performance of journalist in this area. While the code of conduct for the practice of journalism is well understood by many journalists through the numerous training in colleges, Media Council led forums and also in in-house training, the gaps in performances continue to cause concern among various stakeholders. Security chiefs and media practitioners have often been at loggerheads over the mannerism of coverage of sensitive security related issues. A case in point is during the Westgate mall attack where more than 60 people were killed.

Objectives

The monitoring aimed at:

a). Determine the incidence and extent to which the code of conduct for the practice of journalism in Kenya was adhered to or otherwise during the reporting and news dissemination of the security issues.

b). Conduct comparative content of how security issues were covered by the media with specific focus on print and TV media platforms in Kenya.

c). Undertake an objective framing analysis of how the media covered security issues to find out the main thematic areas of focus and manner in which security stories were framed.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Role of the media in reporting insecurity

The media has great power in contemporary society.

They publish, present, broadcast and transmit reports about various insecurity issues that attract public’s attention (Pratt, 2007). While the media as the watchdog of society has been touted for its critical role as an agent for social change and transformation, it is vested with a lot of responsibilities to this end. It educates, informs and corrects misconceptions and creates a better under-standing of a situation.

In pro-active news gathering, the media can take control of the flow of information by conceiving their own story ideas, hunting up events for coverage or defining problems for coverage and agenda setting. They can also gather news by questioning the message of the sources and researching causes, consequences and context on occurrences such as insecurity. When covering national security issues, journalists may encounter dilemmas over handling classified information or information that may provide as assistance to those who would do harm to the country. Sometimes exposing the deaths and casualties resulting from insecurity exposes the ineffectiveness of a country’s security machinations to the terror groups.

The media publish reports on crime and other security threats in a populist and sensational manner and use different techniques to attract people’s attention. Their selective reports about crimes do not reflect the nature and extent of crime presented in official statistics and victimization surveys (Surette, 1998).

The media may play critical roles in the prevention and management of conflict that causes insecurity, as well as deliberately or inadvertently driving conflict that may lead to insecurity. Positive roles in promoting peace and security may include: linking citizens to state; changing attitudes and behaviors; providing early warning of divisive issues or instability; mitigating conflict through balanced reporting; promoting reconciliation.

According to Jones (2011), some of the expected roles of the media in ensuring security/peacekeeping include: increasing the quantity and quality of public communication as it relates to attacks and more especially on how those living in affected areas should behave and respond; providing early warnings of situations that might lead to conflict as well as alerting leaders and attentive publics to opportunities for increasing understanding; stimulating the use of mechanism such as negotiation, mediation and arbitration for conflict resolution and management and providing information that facilitates these processes; helping to create a mood in which solutions are more likely to be sought and accepted; mobilizing or helping to establish contacts among those interests in finding peaceful solutions; and helping to build opinions.

The United Nations Human Settlement Programme (HABITAT) in the report Enhancing Urban Safety and Security: Global Report on Human Settlement notes: “The perception of insecurity depends largely upon flow of information that residents receive many sources.” The report notes that the content and style of the media, whether newspaper or television, have an enormous impact on public perception of the conditions that people believe are prevalent within their environment. Whether these perceptions are exaggerated or not, they depend upon individual media sources, how the stories are communicated and how public authorities respond. The report notes that in the era of global communications, the role of the media is central in both local and international perceptions of safety and security.

The media are not merely transmitters of messages from the sources to the recipients. They are much more than that. They also construct social reality. By focusing on specific issues, specific crime phenomenon and by using special sensationalistic style of reporting, the media can influence public opinion and pre-define public debate. The media manipulate public perception by over-representing violent crimes, presenting crime events as if they were episodes and supporting the belief that crime is a result of individual deviance rather than wider social problems (Bu?ar-Ru?man and Meško, 2006).

The media also simplify crime and insecurity problems and emphasize law enforcement solutions. They focus primarily on stories about dramatic, unusual and violent crimes, with emphasis on stranger-to-stranger offending. The presentation of crime and security issues in the media is influenced by peoples’ perception of threat of crime and, at the same time, exerts a substantial influence on the public’s fear of crime. The media performs a variety of tasks amongst which the most important are informing people about crime and deviancy, constructing public image of crime, promoting social morality and creating an anti-criminal climate, exercising control over criminal justice administration and the mobilizing people for crime detection and investigation

Challenges of media reporting on insecurity

The role of the media is to report the truth in an objective and factual way without taking sides. The press serves not as the watchdog of the society in terms if probing and reporting on the ills of the society but can also serve as a catalyst of national development and a forum for the enhancement of the values of democracy. It is a weapon for the propagation of peace and stability in the society.

Mass media are a basic source of information on crime for citizens. They are important actors in the processes of construction of social meanings. They give the facts an existence as public events by making them visible. They do not offer an aseptic treatment of the information, but give a certain character to the facts (Cohen, 1990; Tuchman, 1978).

The press serves not only as a watchdog of the society in terms of probing and reporting on the ill in the society, but can also serve as a weapon for the propagation of peace and stability. One such role vested on the media is during times of insecurity. However, the media faces a number of challenges in performing this role. According to Caparini (2004), a number of trends threaten to hinder the media’s ability to ethically and professionally report on issues of insecurity. Such issues include the following:

Security secrecy measures

This occurs when there is an emphasis on government secrecy; restrictions on information available to the public and ostracism of critical journalists have had a significant impact on the media.

The ‘dumbing-down’ of news

An increasing trend towards entertainment news and a decline in serious public affairs; journalism imposes serious constraints on reporting of complex security-related issues.

The monopolization of media ownership

The increasing ownership of the media by conglomerates reduces the spectrum of perspectives published and undermines independent and critical journalism with regards to security issues.

Reliance on official sources

The quest for objectivity can lead to reliance on official government sources, making it more difficult to present an alternative perspective which is balanced and objective.

Judicial deference

In countries where judicial deference is common, courts are likely to side with the government on issues pitting claims of national security against press freedom.

Globally, the state and the media are perennially at loggerheads especially on the latter’s fight for freedom of expression. According to the media rights organisation, Article 19, international law recognizes the cardinal role of the state to defend human rights of its people. States Article 19: “It is only logical that when a situation arises which threatens the continued existence of the state, and thereby of the human rights of the entire population, international law permits certain proportionate measures to counter that threat. This includes restrictions on freedom of expression, such as prohibition on divulging troop movements, revealing military encryption codes or inciting desertion. All the international instruments which guarantee the right to freedom of expression also recognize national security as a legitimate ground for limiting that right”.

Largely, the conflict between the media and the state security machinery revolves around the government’s expectations of safeguarding national security on one hand, and the media’s quest for access to information on the other. Where the government would find it prudent to hoard, hide or obfuscate sensitive information, the media feels they should publish such information to meet the public’s right to know.

The review of media reporting shows that one of the main problems in all countries was the influence of politics and governments (including police) on media reporting. In some countries, criminality and insecurity in the periodical press are still skillfully used by a large number of political actors and interests (Bu?ar-Ru?man and Meško 2006).

State secrets and public’s need to know: Security perspective

Governments world over are prone to muzzle democratic discourse through the media and suppress free speech in the guise and pretense of protecting national security interests. Article 35 of the Kenyan Constitution guarantees every citizen the right of access to information held by the state. On the other hand, the Government flow of information requires information to be classified so that access to information is restricted on ‘need to know’. Where security issues are involved, the public believes it is the right of every citizen to know everything in Government while the security machinery in government believes that there are limitations on what information should be laid bare in the public domain.

The greatest limitation to the legal sanctity of state secrecy principle is its potential to breed corruption and impunity under the guise of national security. Some of the ills that have sprouted and have been nourished by the principle of state secrecy include the abuse of power within state security organs which include chronic nepotism in employment, tribalism, and indiscriminate promotions (Wall, 2007).

The intricacy of state secrets is created by the government’s desire to safeguard sensitive national security information on one hand, and the media’s quest for access to information on the other. The state security machinery sometimes considers it prudent to hoard, conceal or obfuscate sensitive information.

News tells the public what has occurred, what is occurring and what is most likely to occur. It is consequently noted that the media has often failed to come out clearly on certain security issues such as travel advisories. It is noted that the mainstream media never has any information on these and members of the public only get the information through social media. The media exaggerates issues even when there is no cause for alarm. The way the media raises issues makes people have a perception about a security aspect, area, legislation that could be wrong. As a result, the security forces prefer to retain any sensitive form of information rather than allow the media to muddle it through misrepresentation and mis-quoting.

Relationship between the media and security forces: frosty of cordial?

The relationship between the media and security institutions is necessarily one of tension, due to differing institutional cultures and goals. Nevertheless, according to Caparini (2004), the media and security sector are mutually dependent and must cooperate to educate the public and hold government to account over security policy:

1. The relationship between the media and the security forces is symbiotic. The security officials need the media to inform the public about its role and maintain public support. While independent reporting is necessary to hold the security forces to account, the media are largely dependent on the security forces for information.

2. During armed conflict the media are essential for informing the public about security operations, but face restrictions from security machinery who are mostly afraid of disclosure of their counter-strategies to the attackers through the media. Embedding journalists can improve media-military cooperation, but can also undermine objectivity.

3. A cooperative relationship between the security forces and the media can help to educate the public, but risks undermining media scrutiny of the Security forces. Media scrutiny of the security forces can establish accountability for specific incidents, but has less influence on policy.

4. The intelligence sector poses a number of special challenges for the media. The necessity for secrecy creates the risk of over-reliance on official information and manipulation of information provided to journalists.

Covering security matters enables members of the public get the right information about the situation in the country, but when security apparatus are found to have failed, they blame journalists for exposing them. This happens globally even in developed countries. There is also the fear of being attacked or killed if one reports wrongly or reveals too much because security involves military or police. This then places the journalist in difficult predicament of whether they should cover the story and risk their existence or let go of an otherwise relevant story in public interest.

The danger of covering security; threats faced by journalist

The fact that the pursuit of news possesses a great danger to journalist themselves cannot be denied. Ordinarily, journalists and editors face ever constant threats and dangers in the course of their work, duties and assignment but rarely addressed. More often than not, journalists and editors are invisible, ill-prepared and rarely acknowledged as some of the most exposed and most likely to face harm and ultimately, death in their endeavours to sniff out, give form, content and nature to the odd occurrence, event and incident, that we constantly crave as News.

For the general news consumers, journalists and editors are heroes when satisfying our natural instincts for travails of our mundane existence, satiating our morbid curiosity, bring home the horror and pain of far off disasters and wars to our living rooms. Rarely do the general news consumers ever pause and wonder – how do the journalists and editors survive the terror attacks, the bombings, the bloody fighting, the raging fires, the flash-floods, the earthquakes; the landslides and the disease pandemics.

Some of the areas where insecurity has occurred in Kenya has seen journalist reporting without adequate protective gear. From the Westgate Mall Terrorist attack of September 2013 to other subsequent terror attacks scene in Mombasa, Nairobi and elsewhere in Mandera, Wajir, Baringo or Bugoma and most recently in Mpeketoni carnage; the journalists were conspicuous for their lack of adequate and or proper kitting yet were expected to satiate the news consumers demand for updated and current reportage as the crisis unfolded. This can be seen to be in sharp contrast to the security forces who were attending to the same scenes. The security forces personnel were well-kitted, trained and inducted – received proper safety and security briefing – were well supported in terms of their emotional well-being (Trauma Counselling) enjoyed other rapid response support network and infrastructure.

Media reporting of insecurity: A case of Israel

Media coverage on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict generates more complaints about media bias than any other news subject. This is due to the fact that the Israeli media do not focus on the wreckage and casualties of their side of battle due to patriotism and in effect under-represent reality and hence the skew and bias. The media in Israel are very patriotic and cautious when reporting issues of security in Israel. Following the holocaust experience and the consequent fights and attacks on the nation of Israel, no reporter or editor wanted to be accused of endangering Jewish lives in their reporting (Peri, 2004)

The choice of words in reporting the insecurity in Israel has been marked by high degree of bridling on the side of journalist. For example, the Glasgow Media Group analysis found words such as "murder", "atrocity", "lynching", "savage”, “cold-blooded killing" and “barbaric” were used to describe Israeli deaths, including of Israeli soldiers, whilst they were not used to describe Palestinian deaths. Given that the Israeli occupation and its military control is quite absent – it is difficult to understand why Palestinians are fighting. Audiences gain an under-standing of Israeli motives for violence while Palestinian violence seems senseless (Robinson, 2009).

Another fact to note is that Israeli military is highly secretive and tactful in the amount of information divulged for public consumption through the media. However, the interaction between the media and state security hierarchy is cordial and open. The journalists are taken on state security awareness programmer and sensitized how to handle the information they get to ensure it does not harm national security interests.

Media perceptions are critical in every modern form of insecurity reporting, but this has been particularly so in recent Israeli-Gaza conflicts. Israel is sensitive to international criticism that is has used its firepower indiscriminately, resulting in disproportionate number of civilian casualties. Unlike conflicts in Libya, Syria and elsewhere in the Middle East, during Israel’s military campaign, Operation Protective Edge, there was intense media coverage with reporters roaming relatively free on both sides.

An important lesson to learn from the Israeli situation is that the power of the media in reporting, analyzing, and capturing images of military involvement around the world must be considered in the forging and execution of national security decision making. Failure to appreciate the media's influence will likely result in eroding public support for national strategy and policy reversals. Although the media is often portrayed as the villain in national security decision making, it performs important role.

Press freedom and national security in the United States

The prominence given to the concept of a free and independent press distinguishes the United States for its dedication to both a robust marketplace of ideas and a government accountable to the people. While there is seldom disagreement over the need to maintain both a strong national defense and an autonomous press, differences in opinion occur when the two are perceived to overlap. At no time is this conflict more evident than when media outlets elect to publish classified information which is information identified by the government as necessary to withhold in the interest of national security.

According to Ross (2011), achieving consensus on the proper balance between media press freedom that leads to openness and secrecy has remained elusive. Debate over this dichotomy between the perceived need to both disclose and withhold information has persisted among academic and legal scholars, government officials, and the public. The intensity and longevity of this debate can be attributed to the deep convictions held by advocates on both sides of the issue.

Ross further argues that the only effective restraint upon executive policy and power in the areas of national defense and international affairs may lie in an enlightened citizenry – in an informed and critical public opinion which alone can here protect the values of democratic government. For this reason, it is perhaps here that a press that is alert, aware, and free most vitally serves the basic purpose of the First Amendment. For without an informed and free press there cannot be an enlightened people (Ross, 2011).

But this autonomy cuts both ways. The press is free to do battle against secrecy and deception in government. But the press cannot expect from the Constitution any guarantee that it will succeed. There is no constitutional right to have access to particular government information, or to require openness from the bureaucracy. The public’s interest in knowing about its government is protected by the guarantee of a Free Press, but the protection is indirect. The Constitution itself is neither a Freedom of Information Act nor an Official Secrets Act.

The dilemma of which is should be held in priority than the other between national security and press freedom is a bruising intellectual battle that often ends inconclusively. The United States with its rich constitutional privileges founded on basic institutional and individual rights and freedoms faces this challenge as technological advance-ment increases with global threats on national and international insecurity. The question is how both the institution of the media and the security forces can co-exist without jeopardizing the functionality, rights and existence of the other.

METHODOLOGY

Content Analysis methodology was used in this study. Two media platforms; print and TV were analyzed. Quantitative and qualitative methods of data analysis and interpretation were used to synthesize the collected data into the findings of this study. The basis of media monitoring which strongly guided the adoption of the code sheet that was used for this study is the code of conduct and ethics in the Media Council Act, 2013. Data mined for this analysis specifically constitute coverage on security in the sampled media houses. Data analysis was loaded into code sheet developed using SPSS software and analysis was done using the same software.

This study looked at 4 TV stations and 3 daily newspapers for a period of six months in 2014. The selection of the TVs and newspapers was selected based on the rating on reach and share of the Kenya audience research foundation of Kenya. The 9 p.m. news programmes on TV were the main focus. The TVs monitored were NTV, KTN, CTV and KBC. The newspapers monitored were The Standard, The People and The Daily Nation

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

Frequency of articles and news clips distribution per media platform.

During the period of monitoring the highest frequency of articles were in the print media platform and totaled 62% while those on the TV platform were 38%. This shows that print media offered a better platform for discourses on insecurity issues during that time. The focus of the security stories was majorly on the news segments of TV and print media platforms (Table 1).

Frequency distribution of articles/clips per specific media house

The Daily Nation had the highest percentage of articles on insecurity with 27.3% of the articles followed by the Standard at 16.8%.Similalry on the TV platform, CTV led in frequency of articles related to insecurity at 11.8% of all the print and TV articles and clips analyzed followed by NTV at 10.1% (table 2).

Separation of facts and opinions in the coverage of issues on security

Separation of facts and opinions is an important ethical code that is found in article 1 of the code of conduct for practice of journalism. A few incidences were noted where some article and TV clips did not separate facts and opinions. The Star Newspaper had 5 incidences which indicated that the facts and opinions were not separated (Table 3).

The standard had 3 while the Nation had 2 articles. The separation of facts and opinion ensures that journalist report objectively and impartially on sensitive issues related to insecurity. Article 1 of the code of conduct states that a person subject to the Act shall treat all subjects of news coverage with respect and dignity, showing particular compassion to victims of crime or tragedy. A person subject to this Act shall seek to understand the diversity of their community and inform the public without bias or stereotype and present a diversity of expressions, opinions, and ideas in context.

Tonality of news presentation on issue of insecurity

17% of the news articles and TV clips analyzed were positive in tonality, 9% were negative while 74% being the majority were neutral and carried factual information on insecurity without injecting any form of opinion or comments that might have been considered negative or positive (Figure 1). Most of the media monitored had negative and positive perspectives and approaches to the issue of insecurity in the country. The negative stories focused on aspects and angles that would incite ethnic, religious and other forms of conflicts without giving clear adequate background information about the nature of such conflict. Negative stories also emphasized the inability of the government to tackle the insecurity issue without clarifying what had been done.

Prominence accorded to insecurity reporting in media platforms

Prominence of security coverage in the media was evident with 57 articles appearing on the front page of the leading daily newspapers during the period of monitoring (Table 4). 64 news stories were reported in the first block of the TV news programme. The first block of the TV news is the cluster of the first news items before advertisement breaks. This is an indication that stories on security attracted prominent media coverage largely because of the public interest nature of such occurrences as the Mpeketoni and Mandera attacks.

The more violent is the state of insecurity, the greater the chance of it being reported about on the front page of the paper. The criteria underlying the selection process is newsworthiness. It means that certain characteristics of the events as represented especially in violent insecurity news attracts greater interest than others and is therefore considered to be more “noteworthy” than others.

Insecurity specific topical coverage in media platforms

63% of insecurity reporting was related to terrorism while 25% was related to security operations by state machinery (Figure 2). Other security reporting was related to ethnic conflicts, corruption in security sector, general crime and burglary and theft and banditry. Generally, the most covered issue as relating to insecurity was on terrorism and security operations which largely focused on what the government was doing to improve the situations in affected regions. Both of these issues had the highest frequency in both print and TV platforms. Some of the other issues included ethnic related conflict, corruption in security operations, crime and burglary, theft and banditry and legislation which was on discussions in parliament relating to insecurity.

Who are quoted as news sources when reporting insecurity in Kenyan media?

Government officials were most quoted with reference to the issue of insecurity at 44% (Figure 3). victims was also quoted largely in both print and TV platforms and consisted 25% of the articles and clips analyzed. Some journalist who did feature stories and who did first-hand account of the occurrences during attacks like in Mpeketoni were also considered as news sources and counted for 7% of the articles and news clips analyzed. Article 4 (2) states that journalist should identify sources whenever possible. Confidential sources shall be used only when it is clearly in public interest to gather or convey important information or when a person providing information might be harmed.

Frames used when doing stories on insecurity in Kenya

The highest percentage of stories in both print and TV platforms were based on responsibility frames at 44%, meaning that they framed and focused on the responsibility of the state and the citizens in ensuring peace and security within their regions (Figure 4). 31% of the stories were largely framed and focused on conflict while 21% were on human interest frames and focused on the plight and suffering of those affected by insecurity in various regions. In reaching such an enormous audience, the media can focus public awareness on national security decision making to such a degree that participants in the process are more vigilant in seeking solutions. This can be achieved more by the adoption of various frames through which the media packages its information on security matters. When national objectives are unclear, the media can then facilitate a reexamination of policies on security intervention through framing and critical analysis of underlying circumstances.

Level of participation of victims when reporting insecurity issues in media

Victims are very important sources of news stories with an element of credibility and first-hand experience which is valuable to media audiences (Figure 5). 32% of newspaper articles and TV news clips included victims/these affected voices in the story. In 8%, the stories excluded the victim’s voices which would have otherwise been considered very important and useful in the understanding of the situation of insecurity.

Although some people might get information about insecurity and violence from personal experience as victims, most do not experience crime and violence personally. Instead much of their information or perceptions about crime come from the news. Therefore, the victims accounts of crime and insecurity is very important in the media. While victims’ voice is helpful in enhancing the credibility of a story, journalist should exercise adequate care in how they extract information form the victims. They should consider that some might be traumatized from their losses and observance of article 14 of the code of conduct in important. The article states that, in cases involving personal grief or shock, inquiries shall be made with sensitivity and discretion. In hospitals, journalists shall identify themselves and obtain permission from a responsible executive before entering non-public areas of hospitals or similar institutions to pursue enquiries.

Nature of headlines used when reporting insecurity stories

Largely the headlines of stories relating to insecurity were descriptive and informative and did not seek to incite or provoke any community to violence or vengeance (Figure 6. This was 80% of the newspaper article and TV clips analyzed.18% of the articles analyzed reflected the content of the stories that it published. While 1.7% of the articles had sensational and unjustified news aspects in the story. Some of the sensational stories were found in the Star and on KTN.

Article 1 (10) states that headings shall reflect and justify the matter printed under them. Headings containing allegations made in statements shall either identify the body or the source making them or at least carry quota-tion marks. This protects audiences from sensational, unjustified headings that are meant to create appetite for the news yet they do not have any news value.

Using emotional and imprecise words when doing stories on insecurity

The highly used word when reporting on insecurity in both newspaper and TV stories was terrorist/terrorism at 34% (Figure 7). Massacre was used in 18% of the stories while ethnic hate was used in 10% if the stories. Some other words identified included extremists, tragedy, devastated and hate mongers in stories analyzed.

In acknowledging their innate capacity as mediators, and applying basic conflict analysis, conflict-sensitive journalists apply more rigorous scrutiny to the words and images they apply in their reporting: Avoiding emotional and imprecise words such as massacre and genocide, terrorist, fanatic and extremist. Call people by what they call themselves. Avoid words like devastated, tragic and terrorized.

Word choice is a key tool reporters use to subtly convey bias and negative connotations in their stories. Media reporters must be aware of this in order to protect their audiences from bias quietly injected in the new stories. Words are never created equal. Even synonyms vary as far as connotations and because of this, it is very important to consider every word especially when reporting on sensitive matters such as insecurity. Reporters should as; is this best possible choice of word here? Is this the least way this idea could have been phrased?

Sources of insecurity as attributed in the news story

Very often, the media state the sources of insecurity as an element of its news reporting (Figure 8).

The main problem is the selective media reports about insecurity and its causes, which sometimes do not reflect the nature and extent of insecurity on the ground. The convoluted and sensitivity of underlying causes of insecurity sometimes makes it difficult to clearly state the causes of insecurity in news reporting. This has a great influence on people, their understanding and interpretation of causes of insecurity and also on the creation of myths about insecurity. The media ought to be more aware of the variety of tasks they perform. For them truthful and accurate reporting about the nature and extent of crime should always be more important than sensational, profit oriented reporting.

Use of bloody, gruesome and inappropriate pictures when doing stories on insecurity

5% of the stories analyzed in both print and TV had bloody, gruesome and unpleasant photographs and scenes published (Figure 9). Article 10 of the code states that publication of photographs showing mutilated bodies, bloody incidents and abhorrent scenes shall be avoided unless the publication or broadcast of such photographs will serve the public interest. Where possible an alert shall be issued to warn viewers or readers of the information being published.

During security attacks, the propensity to publish bloody and gruesome images of the victims is always prevalent among journalist in their desire to show the “reality on the ground” kind of reporting. Such reporting sometimes is done in the name of “public interest” but their impact is less considered during editorial decisions making.

Once images of violence and tragedy have been produced, editors and producers face challenges in deciding whether to use them. They must consider the role played by professional censorship, the tolerance of readers and viewers who will be the consumers of such images. Sometimes, editors choose to attach bloody and gruesome images in their stories in the name of public interest.

By using bloody and gruesome images when reporting on insecurity, journalists turn such reporting into a spectacle of blood and gore and indecency and hence loose the focus of the story and they consequently cheapen human life while giving the impression to people that life does not matter. However, some media houses in Kenya have in the past defended their use of the graphic images and say the move was justified editorially to convey the scale of the "dramatic and gruesome" events all in the public interest.

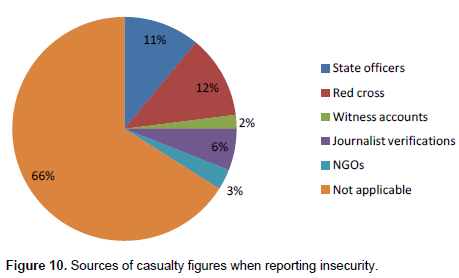

Who do journalists quote as their sources of casualty figures during insecurity reporting?

States officers and Red Cross society were the highest informants in terms of the casualties at 11 and 12% respectively (Figure 10). Other sources of information regarding the casualties resulting from insecurity were journalist verification and eye witness accounts at 6 and 2% respectively.

In any state of insecurity, the resulting chaos, threats from militias, security forces operations and fast moving events present reporters with the challenge of verifying and confirming casualties and deaths which they aim to relay to the vast majority of anxious audiences. Sometimes the figures as presented by some of the news sources are barely credible due to the tinge of propaganda and manipulation that is involved with an aim of projecting an advantageous position through the media.

The onus of verifying some of the casualty figures rest with reporters who are sometimes incapacitated by the challenge of insecurity, inadequate infrastructure that affects their mobility and the issue of incredible news sources. Considerably, humanitarian organizations like the red cross project more credible figures on casualties and victims because they are mostly involved on groundwork humanitarian assistance, the confidence they inspire from some of the victims and also the way they are viewed by some of the militants as being purely humanitarian and with no interest in the conflict.

The use of police or court officials is also faulted for the reason that it often leads to decontextualized reporting, one in which the reporter denies the audience the necessary background to put the story in context. The reporter is likely to fail to ask: was it (the crime) the act of an isolated offender or was it part of an organized effort citizens should be aware of? If it was the former, what brought the perpetrators to the point? Are there social or ethnic or community pressures in play? How many such incidences have there been, and to what effect?

The use of expert’s opinion in the analysis of security news stories

58% of the news stories analyzed in both print and TV platforms did not use expert voices/analysis in their reporting. 21% incorporated expert opinion while 21% were purely stories that did not need the inclusion of expert opinion.

The use of expert’s opinion in news analysis of security matters can be an important component of news programmes (Figure 11).

The journalist's freedom of choosing the content depends on external factors and events; therefore, the media cannot be always blamed for sensationalist reports and intentional misleading of the public. Myths about insecurity are often problems, on which light would also have to be shed from other points of view. This is where expert opinion is needed. One of such myth was created about. The media play an important role in the identification and creation of myths on insecurity and are not just unbiased reporters about criminal events

Media focus on human rights violations during security operations

25% of the newspaper articles and TV clips analyzed focused on the human rights aspect of the security operations (Figure 12). This involved either the massacres or the resulting interventions of the security machinery.

19% did not focus on any human rights violations during the period of monitoring.

Investigative journalism and adversarial journalism serve a purpose in challenging government officials and policies on human rights issues violated during security operations. The media sometimes emerge as the only visible counter to the government's national security policy and strategy the only check on potential government excesses. And therein lies the most important and healthy outcome of the media's dominating influence on national security decision making-maintaining vigilance in the process.

CONCLUSION

When reporting on insecurity, media practitioners should adhere to the Code of Conduct for the Practice of Journalism in Kenya, by keeping the public informed without contributing unduly to the aims of criminals and terrorists and avoiding sensational news and images that help criminals sustain their activities. Indeed, media professionals should be aware of the sensitive nature of media reports on crime and terrorism and should in particular not offer criminals and terrorists a platform for publicity and self-aggrandizement.

The media present a picture of being “reactive” rather than “proactive” in relation to reporting insecurity in Kenya. For the most part, the media seem unwilling or unable to recognize the implications of their construction of news and other stories, and broader entertainment offering, on race and ethnic relations. To some extent, the media have done little to change their fundamental practices, particularly in relation to news. The press, in particular, continues to resist any action which it perceives might be construed as an infringement on its freedom to continue to behave as it has in the past. The media continue to depend in large part on the flow of media releases from humanitarian organizations and state security machinery as their primary sources, using these as points of departure to seek comment etc. Thus the control of the flow of news becomes crucial.

As witnessed in Mpeketoni, the outbreak of insecurity is sometimes a result of underlying conflicts and ethnic tension. The Media may play critical roles in the prevention and management of conflict, as well as deliberately or inadvertently driving conflict that may lead to insecurity. Positive roles in promoting peace and security may include: linking citizens to state; changing attitudes and behaviours; providing early warning of divisive issues or instability; mitigating conflict through balanced reporting; promoting reconciliation.

Negative or destabilizing roles of media may include: “hate speech” and incitement to violence; inaccurate reporting and incendiary rumour; deliberate under-reporting and misreporting; over-reporting and sensationalisation of insecurity, violence and insecurity; the sudden collapse of media coverage. Challenges to good media practice in conflict-affected countries include: distribution and access costs, particularly where roads and electricity are lacking; financial sustainability and dependence on foreign aid; technical sustainability, including hardware costs and maintenance; maintaining professional journalistic standards; representation of women and their interests; intimidation of journalists and sources through threats, violence or litigation; political patronage and interference.

Sensationalism of stories relating to insecurity and violence is common worldwide, tends to heighten feelings of insecurity among ordinary people, and can promote a siege mentality. Rumours and misinformation can thrive in contexts of inadequate or partial access to reliable alternative sources of information.

RECOMMENDATIONS

1. The separation of facts and opinion when reporting insecurity should be clearly upheld. The use of expert voice during news analysis of security issues is important to allowing in-depth information with expert opinions. This is a better alternative than expressing opinionated news stories.

2. Journalists should choose their words very carefully when reporting on conflict instigated insecurity like the Mpeketoni attacks. Conflict sensitive reporting gives guidelines of some of the words that should be avoided when reporting on fragile situations that involve ethnic hate and underlying historical injustices that can flare up conflict and insecurity.

3. The media have a responsibility for contextualized, meaningful reporting where news programmes have adequate background information on historical, cultural and even political perspectives of conflicts causing insecurity. This allows audiences to make informed decisions.

4. The media should also offer victims of attacks and violent crimes the opportunity to express their feelings on issues of insecurity. While the victims account offers news report credibility, it also serves to create a clear picture of the insecurity situation as illustrated by victims themselves.

5. Journalists should also focus on the human rights perspectives when reporting on insecurity operations by state machinery and also by vigilante and terrorist groups. The media should report objectively and aim to express openly how human rights issues are being treated.

6. The use of gruesome and unpleasant photographs and scenes should be avoided since it is in violation of Article 10 of the code which states that publication of photo-graphs showing mutilated bodies, bloody incidents and abhorrent scenes shall be avoided unless the publication or broadcast of such photographs will serve the public interest.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

| BuÄar-RuÄman A, Meško G (2006). Presentation of Police Activities in the Mass Media, Varstvoslovje 8(3/4):223-234 | ||||

| Caparini M (2004). Transforming Media Rreporting of Security Operations; Assessing Process and Progress. Oxford University Press, Oxford. | ||||

| Cohen S (1990). Folk Devils and Moral Panics, Cambridge, Basil Blackwell. | ||||

| Jones OD (2011). The role of the media in peace building. Int. J. Conflict Stud. 8(5):19-27. | ||||

| Peri Y (2004). Telepopulism: Media and Politics in Israel, Stanford, CA: Stanford UP. | ||||

| Pratt J (2007). Penal Populism, London, Routledge. | ||||

| Robinson L (2009). National security, law and the media; Shaping public perception. International Law Studies. Global Legal Challenges p.83. | ||||

| Surette R (1998). Media, Crime and Criminal Justice: Images and Realities, Belmont, Wadsworth. | ||||

| Tuchman G (1978). Making News. A study in the construction of reality, New York-London, The Free Press. | ||||

| Wall D (2007). The role of the media in generating insecurity and influencing perceptions of cybercrime, 'Media and Insecurity', Ljubljana, Faculty of Criminal Justice. | ||||

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0