ABSTRACT

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) was the only country to ban women from driving until a royal decree changed this in June 2018. The controversy before and after the ban gained media attention and is the foundation for this study, examining how US and UK media covered the women driving ban. Framing theory and thematic analysis were used to examine 80 articles randomly chosen from 10 prominent and most trusted US and UK news outlets before and after the ban. The study found that the majority of the coverage was supportive of women driving before and after the ban in the KSA, but coverage of KSA women vividly shifted after lifting the driving ban. Western ideologies and perspectives, present in most articles, did not consider the main differences between cultures. False information and exaggerations in some articles provided inaccurate information about women in the KSA.

Key words: Saudi women, framing theory, thematic analysis, US and UK media coverage.

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is home to more than 34 million people, of whom 20 million are Saudis, according to the General Authority for Statistics (2020). Empowering women is a priority for the Saudi government, with women playing significant roles in education, economy, health, and politics (AlMunajjed, 2009; Browne, 2018). In education, Saudi women are slightly better educated than Saudi men, according to the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS) (2018). Around 50% of university students are women, as are half of the doctors and teachers in the KSA (Lapovsky, 2016; Nereim and Abu-Nasr, 2015; UIS, 2018). In politics, Saudi women gained equal rights to vote in the 2015 municipal elections, and 20 women were elected (BBC, 2018c; Chulov, 2011), and for the first time, 30 Saudi women joined the country’s advisory body, the Shoura Council in 2013 (Nereim and Abu-Nasr, 2015; Radwan, 2018).

For a long period, however, the KSA was known as the only country to forbid women from driving cars. The breakthrough came on June 24, 2018, when Saudi women received the right to obtain driver licenses, putting an end to one of the major issues facing women in the KSA (Sirgany and Smith-Spark, 2018). It was a remarkable day for many women in KSA who took to the roads shortly after this historic decision. Saudi women applauded the decision by sharing videos and photos of themselves on social media driving cars in celebration (Sant, 2018).

The historic event prompted this investigation and analysis of prominent US and UK news media coverage in the KSA. Specifically, it compared how the media covered the issue before and after the driving ban was lifted. This study sought to identify main themes and tones of US and UK media coverage, adding to the body of knowledge of how Western media portray Saudi women.

Little or no research exists on how both the US and UK media covered the issue of women’s right to drive in the KSA. These two countries have the most trusted media outlets in the world, according to a Reynolds Journalism Institute at the University of Missouri (Kearney, 2017), and both vital key players in the Middle East. The authors used framing theory and thematic analysis to examine how the media covered the events that led to the only country in the world that disallowed women drivers to finally lift its ban.

Image of Saudi Arabia in the media

Throughout history, Arabs and Middle Easterners have been portrayed negatively in the US media due to the nature of the relationship between the West and the Arab countries (Hirchi, 2007). In his book “Orientalism”, Edward Said (1978) believes that the West created the idea of the “East” (Orient) and “West” (the Orient). Said (1978) states that the relationship between the West and the East becomes “us” and “those” or “we” and “others” and because the Middle East embraces different identities and ideologies, it has been considered as “Others” (Said, 1978). A recent study published by the Center for Media Monitoring (CFMM), 2019 at the Muslim Council of Britain analyzed around 11,000 articles for all British media outlets found that 59% of articles associated Muslims with negative behaviors and that the word “Terrorism” is the most theme related to Islam and Muslim (CFMM, 2019).

The KSA is no exception to the negative media campaigns that severely impacted its image, especially after 9/11 (Zhang and Benoit, 2004). A recent study by The Economist and YouGov found that only 4% of Americans consider the KSA to be an ally to the United States (Frankovic, 2018). Such findings present a unique opportunity to explore how the US and UK media portray the advancement of women driving in the KSA.

Brief history of women driving in KSA

In 1957, the KSA announced a decree prohibiting women from driving cars (Perper, 2018). Since then, many women have made efforts to break the driving ban by driving their vehicles in KSA’s streets, but many ended up in custody (Jamjoom, 2013a; Malik, 2011). For instance, in 1990, more than 47 women drove their luxury cars in the capital city of the KSA, Riyadh, but the police stopped them (Jamjoom, 2013b; The New York Times (NYT), 1990). The women then signed a pledge not to drive again (NYT, 1990). Saudis from around the country applauded the women for their bravery and described the incident with positive adjectives like amazing and astounding (NYT, 1990).

In 2011, another group of women launched a social media campaign called ‘Women2Drive’ asking all women to get behind the wheel, defy the ban, and drive throughout the KSA’s streets (Chappell, 2013; Jamjoom, 2013b; Malik, 2011).

In 2013, Saudi women launched another campaign called ‘Oct26driving’ aimed at encouraging all women to protest the ban and drive their cars (Chappell, 2013; Hubbard, 2013; Jamjoom, 2013b; Jamjoom and Smith-Spark, 2013). A royal decree allowing women to drive on June of 2018 ended Saudi women's struggle and put an end to such an issue.

Framing theory

Framing theory, developed by Goffman in 1974, suggests that the way mass media present and convey messages and information affect people’s expectations of the social world around them (Baran and Davis, 2009). Framing theory focuses on how mass media frames its news and information and at the same time how people learn from the news and make sense of their social world (Baran and Davis, 2009). Framing is how journalists shape content “within a familiar frame of reference” (Gorp, 2007: 61) in a way that resonates with their audiences who also share the same frame of reference (Bowe, 2018). These frames include a shared culture and socially defined roles established within the society in which journalists and their publics live.

Mass media can alter perceptions and how people live or communicate with each other (Baran and Davis, 2009). Thus, depicting negative or positive images of Saudi women on the news media may affect perceptions and how people look at Saudi women. As stated by Arendt (2013), “Regular exposure to media stereotypes can contribute to the development of stereotypical memory traces. Once developed, such traces can be reactivated by subsequent (albeit brief) exposure” (p. 830). Framing theory provides a strong foundation for understanding US and UK news media framing of women driving in the KSA before and after lifting the ban and the efforts of Saudi women to gain local and international support (BBC, 2013; Chandler, 2014; Hubbard, 2013; Jamjoom, 2013a, 2013b; Malik, 2011; Jamjoom and Smith-Spark, 2013).

The following research questions informed this study:

RQ1: What general themes and tones emerged when analyzing articles of women driving in KSA across prominent US and UK media outlets during the women driving ban and after lifting the driving ban?

RQ2: To what extent, if any, did prominent US and UK news media provide balanced coverage of women driving in KSA before and after lifting the ban?

A thematic analysis method utilized in this study. The researchers followed Braun and Clarke's (2006) rigorous thematic analysis process by systemically analyzing all data and giving attention to all details to capture patterns across the data. Thematic analysis is a “method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns (themes) within data” (p. 6). Researchers in many fields, including health and well-being (Braun and Clarke, 2014), business (Jones et al., 2011), and media and communication (Lawless and Chen, 2019; Kim and Weaver, 2002) use a thematic analysis method.

Sample

The sample included a set of 80 articles, eight articles from each of 10 prominent and most trusted US and UK news media (Kearney, 2017) that covered the issue of women driving in KSA, which are: The Guardian, The New York Times (NYT), Wall Street Journal (WSJ), CNN, The Independent, BBC, The Washington Post, USA Today, NPR, and Reuters. The researchers chose two periods, before lifting the driving ban and after. This resulted in sample of 48 articles from US media outlets and 32 from UK media outlets.

Procedures

The researchers used the Google search engine to search for the topic under investigation by using two key phrases, women driving in Saudi Arabia and women defy the driving ban in Saudi Arabia. Each news network’s name and year accompanied the keywords (e.g., women driving in Saudi Arabia BBC 2018).

The researchers then selected four articles for each period with a total of eight articles from each of the 10 media outlets. Four stories were the most any one selected medium printed or aired either before or after the ban. The researchers limited the study to 80 articles because the themes and tones were redundant and nothing new emerged in those articles studied during the time period.

The authors followed Braun and Clarke’s (2006) rigorous thematic analysis process to analyze patterns, presence of different opinions (e.g. supporters, opponents, biased or unbiased coverage), and tone of articles (e.g. positive, neutral, negative). Scholars define media bias as the “different impressions created from an objective event by slanting information” (Xiang and Sarvary, 2007: 611). The authors operationalized biased coverage as a news article that selects certain actors, stories, and events to tell one side of the story and overlook other facts and sides. Unbiased coverage provides a neutral tone and includes different actors, stories, and events about the issue under study. We first familiarized ourselves with the data, took notes, generated initial codes, and searched for themes. We then made relationships between codes, themes, and sub-themes. We reviewed and adjusted the themes to reflect on the data (Braun and Clarke, 2006). The researchers followed a detailed codebook during the analysis. After training, we applied human coding, by two experts in the field who followed percent agreement (Allen, 2017), and Pew Research’s Center, 2018 strategies of intercoder tests by randomly choosing at least 6% of articles and rating them independently to obtain an 80% or higher agreement. The researchers randomly chose 10% of articles and conducted the intercoder tests reaching above 95% agreement. The researchers consolidated differences during coding process to ensure validity and reliability of data.

The researchers read each article thoroughly three times to determine certain themes, tones, and objectives. The three times analyses were conducted at a different period of times within six months to ensure accuracy and to reduce any bias or mood influence. The researcher’s expertise of the culture and thorough research of the issue under study helped in understanding the overall aims and the tones of articles.

Subsequently, the researchers applied a computer software analysis, sentiment analysis, as a confirmatory tool for each article to confirm data accuracy, specifically articles’ tones. After analyzing all articles, both researchers reviewed and reconciled the results of the coding process and sentiment analysis. Both researchers agreed upon the themes and tones that emerged after final examination. Researchers then utilized another computer software, Write Words, which generates word frequency for all articles.

RQ1: What general themes and tones emerged when analyzing articles of women driving in KSA across US and UK media outlets during the women driving ban and after lifting the driving ban?

General tones and themes of media coverage

Analysis of all selected articles in this study revealed how US and UK media covered the issue of women driving prior and after lifting the driving ban. Although common themes emerged across both periods, some themes found in articles written before the decision were slightly different from those after lifting the ban.

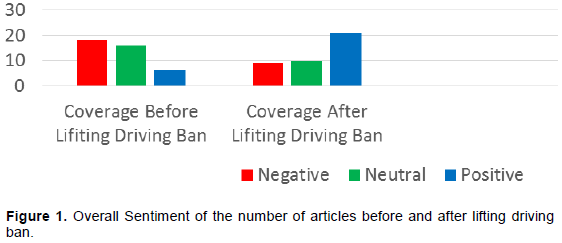

Only six articles written about Saudi women drivers before the ban were positive, however, 21 articles with positive tones emerged from The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, NPR, USA Today, and The Guardian after lifting the driving ban. These articles praised Saudi women, Saudi society, and the government for positive progress and development in the KSA regarding women’s rights (Fahim, 2018). For example, one story described how a Saudi woman celebrated the historical moments by saying, "I feel free like a bird" (Chulov and Alfaour, 2018); another story showed how some Saudi women became interested in getting muscle and sporty cars with 400 horsepower (Stancati, 2018); and another described how police officers gave women drivers flowers and parents gave blessings to their daughters (Chulov and Alfaour, 2018). The overall positive coverage was 34%.

Almost 33% of articles written before and after lifting the driving ban carried a neutral tone. Reuters, The Wall Street Journal, NPR, CNN, and The Independent were more likely to provide neutral coverage about the issue than other media networks. Nevertheless, 34% of overall articles were negative and severely criticized the KSA for a variety of human and women rights issues during coverage of women driving in the KSA (Figure 1).

Articles with negative tones declined by 20% after the KSA announced lifting the driving ban. Negative narratives that remained after lifting the driving ban included the guardianship system, activists’ arrests, the war in Yemen, and other women’s rights issues. The most negative media coverages were in The Independent, NYT, The Washington Post, The Guardian, and USA Today with at least three negative articles for each medium. Most negatives stories attacked Saudi culture, Saudi law system, and the KSA. These attacks included negative phrases, descriptions, and quotes, such as "repressive regime," and "allowing women to drive is a public relations move," in The Guardian (Mahdawi, 2018); "KSA is the worst country for women" (Mahdawi, 2018); "It is outrageous that women are still treated as second-class citizens in Saudi Arabia" in CNN (Smith- Spark, 2018); and "It consigns women as a second-class citizen" (Fisher, 2013). In some NYT and Reuters articles, journalists likened Saudi Arabia’s policy ban on women driving to what is known as ‘the Islamic State (ISIS) and Taliban’ (Coker, 2018a; Hubbard, 2017; Kalin and Dadouch, 2018). In a Washington Post article, the KSA was described as "one of the worst countries for women" (Fisher, 2013). Other news networks used different labels such as a "repressive regime" (Mahdawi, 2018) and described the country as an "absolute monarchy ruled according to Sharia law" (Hubbard, 2017) or "Within Saudi Arabia, genders are segregated under the strict interpretation of Islamic Shariah law known as Wahhabism" (Mayhew, 2014), despite that nothing called ‘Sharia law’ in Islam exists (Landes, 2016). The news media also called the country different names instead of its official name such as "ultraconservative kingdom" in the NYT (Hubbard, 2017), "the oil-rich kingdom" in The Independent (Mayhew, 2014), "the conservative Muslim Kingdom" in Reuters (Dadouch, 2018), and "the struggle is rooted in the kingdom’s hard-line interpretation of Islam, known as Wahabbism" as in The Washington Post (Al-Shihri and Batrawy, 2013).

The word frequency count software indicated certain words or terminologies found across all articles. The study included only significant words and concepts that are important (Table 1).

Themes before lift of driving ban

Themes in articles written before KSA’s decision to lift the driving ban mainly focused on guardianship, religion, women’s rights, driving campaigns, and Shoura council and municipal elections (Table 2).

Themes after lift of driving ban

Five themes emerged after allowing women to drive:

(1) Economic Benefits and Vision 2030: Economic benefits under vision 2030 was the main theme discussed in the articles written after lifting the ban as in The Independent and NPR (e.g., Al Otaibi, 2018; Hvidt, 2018; Sant, 2018).

(2) Driving License: Related stories were about governmental offices readying themselves to issue thousands of women driving licenses and women celebrating their first Saudi driver licenses (Sirgany, 2018).

(3) Driving Schools: Media outlets like BBC, CNN, WSJ, and Reuters (e.g., Al Otaibi, 2018; Jordan, 2018; Sirgany, 2018; Stancati and Abdulaziz, 2018) reported on the thousands of Saudi women signing up for driving lessons and enrolling in private and public schools.

(4) Workforce: The Independent, WSJ, BBC, and USA Today (e.g. Abdulaziz, 2018; Hutcherson, 2018; Hvidt, 2018; Jordan, 2018; Wirtschafter and Rifai, 2018) all discussed how allowing women to drive would boost the number of women in the workforce.

(5) Auto Industry: Themes emerged in USA Today, CNN, and BBC (e.g. Alkhalisi, 2017; Jordan, 2018; Sirgany, 2018; Stancati, 2018; Wirtschafter and Rifai, 2018) about the demand for new cars, increase in auto sales, competition among dealers, and car ads that empower women.

(6) First Time Driving Experiences: News articles in the WSJ, The Washington Post and BBC covered the historic moments with positive narratives, photos, and interviews with first-time Saudi women drivers (e.g., BBC, 2018b; Murphy, 2018; Stancati, 2018; Stancati and Abdulaziz, 2018).

(7) Entertainment: News articles like The Washington Post, Reuters, and NPR also included KSA progress and expansion in the entertainment industry such as opening new cinemas, F-1 car racing, and other entertainment activities (e.g., Baldwin, 2018; Boren, 2018; Sant, 2018).

(8) Guardianship System: This theme emerged in most articles written after lifting the ban in the KSA as in The Washington Post, BBC, NYT (e.g., BBC, 2018a; Coker, 2018b; Murphy, 2018; Smith- Spark, 2018; Takenaga, 2018).

(9) Religious Themes: Religious themes, like Wahhabism, were included in stories by the New York Times and BBC (e.g., BBC, 2018a; Coker, 2018b; Hutcherson, 2018; Sant, 2018; Takenaga, 2018).

(10) Women’s Rights: Status quo of women rights, challenges, and progress discussed in many news articles, like The Independent (e.g., Hvidt, 2018).

(11) Anti-Harassment Law: This new theme emerged in many media outlets, including The Independent and NPR which covered the new law passed by the Saudi government to prevent sexual harassment against women, especially after allowing them to drive (e.g., Al Otaibi, 2018; Sant, 2018).

RQ2: To what extent, if any, did US and UK news media provide balanced coverage of women driving in the KSA before and after lifting the driving ban?

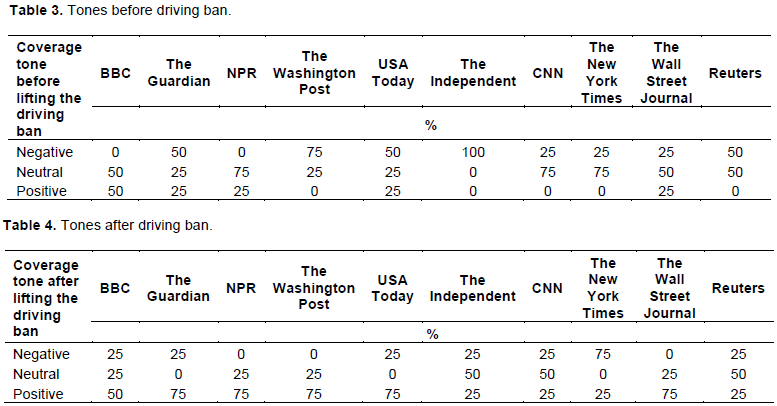

To answer RQ2, the researchers analyzed each article to determine if it provided balanced coverage. Did each article include an overview of the issue by providing information and arguments of both supporters and opponents of women driving in the KSA in a balanced and unbiased way? The study found that most articles written about women driving in the KSA (86%) were supportive and encouraged women to defy the driving ban. These articles included many quotes and citations from women activists, human rights activists and organizations, and in some cases journalists who supported women driving who also, in many cases, criticized the Saudi laws. The remaining articles were balanced (14%), mentioning both supporters’ and opponents’ perspectives and in some cases not citing either side or taking a side on the issue. That was obvious in Reuters, the Wall Street Journal, and BBC stories that provided balanced coverage for both sides before and after the lift of the driving ban. Although the BBC had one negative article written after lifting the driving ban, it generally provided balanced coverage. Like NPR and USA Today, many media were neutral in tones but were supporting women driving in KSA (Tables 3 and 4). Only one article out of the 80 articles in this study vividly opposed women driving, citing opponent voices (Abdel-Raheem, 2013). This article, which appeared in The Guardian in 2013, provided in-depth details about the role of women and how driving a car is something unnecessary for Saudi women at that time.

While most US and UK media outlets supported Saudi women to defy the KSA's driving ban, many articles did not consider the consequences of encouraging women to break the law in the KSA. This was obvious before the announcement of the royal decree that lifted the driving ban, in which many articles encouraged women to put more pressure on the Saudi authorities by continuing their driving publicity campaigns, despite authority warnings. This story angle, however, could have created more risk for women.

Allowing women to drive, however, would increase women’s mobility and role in Saudi society. Women would have access to work and save more money. A report estimated that families would save around $1,000 each month if women drove instead of hiring drivers (Alkhalisi, 2017). Allowing women to drive would also help the Saudi economy to generate around 65% of GDP from the private sector (Alkhalisi, 2017). This decision would generate around $90 billion by 2030 to the Saudi economy (Fattah, 2018). A report estimated that around 15 million women in the KSA could drive (Jordan, 2018). This would give Saudi women more opportunity to participate in joining private and public sectors and reduce the unemployment rate from 11.6 to 7% by 2030 (Jordan, 2018). It would also raise women’s participation in the workforce from 22 to 30% (Jordan, 2018; Turak, 2018). For example, Careem Company, similar to Uber, which operates in more than 14 countries, plans to hire more than 20,000 women drivers by 2020 (Turak, 2018).

The Saudi National Committee for Driving made arrangements and preparations to teach women to dive. Universities are offering courses to on road safety, while private driving schools are training women to drive. Despite the fact that that many women have complained of the high fees associated with taking driving lessons compared to men, experts believe that the use of extra and advanced equipment to teach women how to drive was the reason for higher fees (Al Arabiya, 2018; ECA Group, 2018). The ECA Group (2018), for example, has introduced 6 EF-CAR driving simulators to teach women the basics of road safety as a part of a nationwide campaign to increase women drivers.

The study found that most articles (86%) supported women driving and called for women to defy the ban, but did not discuss other related issues such as the safety of driving or how to create a safe road environment for women, especially in articles written before lifting the ban. A few articles that emerged after lifting the ban, however, discussed the issue of driving safety in the KSA, as in The Guardian (Harrison, 2018). Interestingly, few articles discussed the significance of a safer driving environment after lifting the driving ban. The argument here is that coverage of women driving needed to address and focus on the driving environment, not just political or religious aspects. Unfortunately, most articles written about women driving in KSA encapsulated the issue on the guardianship system, arrests, and in some cases on Wahhabism.

Media outlets also overlooked other significant issues, such as infrastructure readiness for new drivers, or new technologies or policies that the country can use to help new drivers join the road safely. That is, most articles included a focus on cultural perceptions rather than operational issues such as road conditions and driving safety after the announcement to lift the ban. Analysis of articles that were written in US and UK media about women driving after lifting the ban found that 53% of those articles were positive in its tones compared to only 15% of positive coverage before lifting the ban. This makes sense as the KSA was the last country to lift this ban, feeding into the Western media narrative to preserve human dignity and freedoms. Nonetheless, analysis of some media networks unfolded some odd media coverage patterns. For example, the study found that the NYT coverage of women driving in the KSA became more critical and negative in tone after lifting the driving ban compared to articles written before. On the contrary, both US and UK media outlets, such as The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The Independent, BBC, Reuters, USA Today became more neutral and positive in tone after allowing women to drive.

The study also found that most media coverages positioned banning women from driving as a violation of human rights. Media outlets, as well as the Human Rights Watch (HRW) (2013) organization, have criticized the KSA for not allowing women to drive and asked the authorities to revoke this law. Some articles, however, praised the KSA for making some progress regarding women's rights, including allowing Saudi women to vote and run in municipal elections and joining the Shoura Council, the country’s advisory body.

The presence of false information, exaggerations, and inaccurate descriptions of the country were also seen in some articles that provided negative portrayals of women’s conditions or the system in the KSA. Some examples included limited access to education for women (McGveigh, 2013); the driving ban being enforced by the religious police, which the author then retracted after one month of the original article (Chan, 2016); the KSA as the worst country for women (Mahdawi, 2018); and women as second class citizens (Fisher, 2018). Another example of inaccurate information was that a female traffic department would be created under religious agencies (Mayhew, 2014), which never happened. A piece written by The Wahsington Post tried to legitimize what is considered a crime in the Saudi judicial system, such as defending a Saudi activist who publicly insults the religion of Islam and its prophet (The Washington Post, 2013). These demands are legally and socially not acceptable in the KSA as the law prohibits insulting religions or religious values, according to Communications and Information Technology Commission (CITC, 2020; The Anti-Cyber Crime Law). Thus, journalists would benefit from understanding the legalities in foreign countries as well as their values and principles.

Overall, half of the sample appeared to fully embrace Saudi women's achievement during this historic moment by sharing positive stories and images. On the other hand, many stories on women driving incorporated other political issues, such the war on Yemen, to undermine the government efforts of reforms and developments. This was most apparent in the NYT coverage in which the tones for articles written before lifting the driving ban were neutral and suddenly became severely critical after lifting the ban.

In many instances, journalists imposed Western values when framing their stories. The results of the thematic analysis revealed that most articles covering this issue tried to frame Saudi women’s fates and futures as in the hands of men, while the reality is that the relationships between men and women in Saudi society builds on mutual relationships that comprise of rights and duties for both (Human Rights Commission, 2020) This does not mean that there were no shortcomings regarding women rights at the time of the study, but reforms and progress are gradually happening. For instance, women in the KSA receive paid maternity leave ranging from two months and up to three years without losing their jobs. Recently, women are able to have careers such as lawyers and defend cases in courts and hold leadership positions in different ministries in the KSA (Ministry of Justice, 2018). Considerable progress recently has given Saudi women their rights in many areas, including the revocation of what is known as “The Guardianship System” giving women more mobility and freedom. A recent report titled “Women, Business and the Law 2020” by the World Bank (2020), added a new victory for Saudi women ranking the KSA globally first with the largest improvement regarding women’s mobility, workplace, parenthood, economic activity, harassment, and retirement age. Therefore, framing repeated negative images with negative languages about the situation of Saudi women, even during a celebratory moment like lifting the driving ban, may only further enhance a WESTERN stereotype.

This study has identified three limitations. The first one is the use of thematic analysis. The analysis of articles was subjective to the researchers' understanding of the texts, tones, and themes. Although researchers established specific criteria and a codebook to ensure accurate analysis across all chosen articles, there were possibilities that the researchers' subjectivity had some influence on the results. Second, the complexity and overlapping of other issues with the women driving ban could affect the stories' tones. Finally, having 10 media networks and 80 articles could have resulted in a less in-depth analysis of how one particular media network, like The NYT, for instance, covered the issue of women driving in the KSA.

The analysis of articles related to women driving revealed similarities and differences on how the US and UK mainstream media covered the issue in the KSA. Most media outlets provided neutral and positive media coverage after the government allowed women to drive, with a few exceptions. Prior to allowing Saudi women to drive, some US and UK media harshly criticized the KSA with unflattering phrases, descriptions, and misinformation. Being better informed about a nation’s culture and religions may help journalists write articles with less bias or preconceived notions and greater objectivity. It is not being suggested here that journalists are purposely writing bias articles but simply suggesting that a better understanding of others’ cultures can only better inform journalists in their reporting.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Abdel-Raheem A (2013). Word to the west: many Saudi women oppose lifting the driving ban. The Guardian. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

Abdulaziz D (2018). This is happening! Riders hail Saudi Arabia's first female professional drivers. The Wall Street Journal. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Al Arabiya (2018). Saudi national committee for driving ready for women to take the wheel. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Alkhalisi Z (2017). Women driving could rev up Saudi economy. CNN. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Allen M (2017). The sage encyclopedia of communication research methods (Volumes 1-4). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

|

|

|

|

|

Al Otaibi N (2018). Saudi Arabia has lifted the ban on women driving- this is what it means for women's rights. The Independent. Available at: View

|

|

|

|

|

AlMunajjed M (2009). Women's education in Saudi Arabia: The way forward. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Al-Shihri A, Batrawy A (2013). Saudi women drive with little problem. The Washington Post. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Arendt F (2013). Dose-dependent media priming effects of stereotypic newspaper articles on implicit and explicit stereotypes. Journal of Communication 63(5):830-851.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Baldwin A (2018). Saudi woman drives F1 car on historic day. Reuters. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Baran S, Davis D (2009). Mass communication theory: Foundation, ferment, and future (5th edition). Boston, MA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

|

|

|

|

|

BBC (2013). Some Saudi women defy driving ban in day of protest. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

BBC (2018a). Saudi Arabia's ban on women driving officially ends. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

BBC (2018b). I can't believe I'm driving in Saudi Arabia. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

BBC (2018c). Saudi Arabia country profile. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Boren C (2018). Magical: A Saudi Arabian woman drives a formula one car as ban ends. The Washington Post. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Bowe BJ (2018). Permitted to build? Moral foundations in newspaper framing of mosque construction controversies. Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly 95(3):782-810.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Braun V, Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3(2):77-101.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Braun V, Clarke V (2014). What can "thematic analysis" offer health and wellbeing researchers?. International journal of qualitative studies on health and well-being 9:26152.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Browne G (2018). Saudi women 'ready to play a full role in the economy. The National. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Center for Media Monitoring (CFMM) (2019). State of media reporting on Islam and Muslims. The Muslim Council of Britain. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Chan S (2016). Let women drive, a prince in Saudi Arabia urges. The New York Times. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Chandler A (2014). KSA's women problem. The Atlantic. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Chappell B (2013). Saudi women get behind wheel for 'drive-in' protest. NPR. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Chulov M, Alfaour N (2018). I feel free like a bird': Saudi women celebrate as driving ban lifted. The Guardian. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Chulov M (2011). Saudi women to be given right to vote and stand for election in four years. The Guardian. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Coker M (2018a). Saudi women can drive, but here's the real roadblock. The New York Times. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Coker M (2018b). How guardianship laws still control Saudi women. The New York Times. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Communications and Information Technology Commission (CITC, 2020). The anti-cyber crime law. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Dadouch S (2018). Saudi female accident inspectors prepare for women driving. Reuters. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

ECA group (2018). ECA Group's car simulators introduce KSA women to driving and road safety. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Fahim K (2018). Saudi Arabia's women drivers exultantly take the wheel as ban is lifted. The Washington Post. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Fattah Z (2018). KSA's $90 billion reason to allow women to drive. Bloomberg. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Fisher M (2013). Saudi Arabia's oppression of women goes way beyond its ban on driving. The Washington Post. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Frankovic K (2018). Americans had limited trust in Saudi Arabia even before Khashoggi. YouGov. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

General Authority for Statistics (2020). The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: The total population in 2019. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Gorp BV (2007). The constructionist approach to framing: Bringing culture back in. Journal of Communication 57(1):60-78.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Harrison E (2018). The Saudi Arabian women driving forward. The Guardian. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Hirchi M (2007). Media representations of the Middle East. Media Development Journal 54(2):7-11.

|

|

|

|

|

Hubbard B (2013). Saudi women rise up, quietly, and slide into the driver's seat. The New York Times. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Hubbard B (2017, September 26). Saudi Arabia agree to let women drive. The New York Times. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Human Rights Commission (2020). Human rights in the Kingdom. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Human Rights Watch (HRW) (2013). Saudi Arabia: End driving ban for women. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Hutcherson K (2018, June 5). Saudi Arabia issues its first driver's licenses to women. CNN. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Hvidt M (2018). Saudi Arabia lifted its ban on women driving because of economic necessity, not women's rights. The Independent. Available at: View

|

|

|

|

|

Jamjoom M (2013a). KSA issues warning to women drivers, protestors. CNN. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Jamjoom M (2013b). Saudi women's new campaign to end driving ban. CNN. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Jamjoom M, Smith-Spark L (2013). KSA women defy authorities over female driving ban. CNN. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Jones MV, Coviello N, Tang YK (2011). International entrepreneurship research (1989- 2009): A domain ontology and thematic analysis. Journal of business venturing 26(6):632-659.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jordan D (2018). Saudi Arabia job growth likely as woman driver ban ends. BBC. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Kalin S, Dadouch S (2018). Saudi women take victory lap as driving ban end. Reuters. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Kearney M (2017). Trusting news project report 2017: A Reynolds Journalism Institute research project. University of Missouri. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Kim ST, Weaver D (2002). Communication research about the internet: a Thematic meta-analysis. New Media & Society 4(4):518-538.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Landes A (2016). Five myths about sharia. The Washington Post. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Lapovsky L (2016). Behind the niqab: Saudi Arabian women educators. Forbes. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Lawless B, Chen YW (2019). Developing a method of critical thematic analysis for qualitative communication inquiry. Howard Journal of Communications 30(1):92-106.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mahdawi A (2018). Saudi Arabia is not driving change - it is trying to hoodwink the west. The Guardian. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Malik N (2011). KSA's women2Drive campaign is up against society. The Guardian Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Mayhew F (2014). Saudi Arabia could lift ban on women drivers. The Independent. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

McGveigh T (2013). Women's rights supporters condemn Saudi Arabia as activists ordered to jail. The Guardian. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Murphy J (2018). Really happening: Saudi women mark first day of driving with road trips and calls for wider change. The Washington Post. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Nereim V, Abu-Nasr D (2015). Saudi women are joining the workforce in record numbers. Bloomberg. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Perper R (2018). KSA women can now drive - here are the biggest changes they've seen in just over a year. The Business Insider. Available at: View

|

|

|

|

|

Pew Research Center (2018). Content analysis: Human coding of news media. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Radwan R (2018). Saudi women's voices in Shoura council continue to be heard. The Arab News. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Sant S (2018). Saudi Arabia lifts ban on female drivers. NPR. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Sirgany S, Smith- Spark L (2018). Landmark day for Saudi women as kingdom's controversial driving ban ends. CNN.

|

|

|

|

|

Sirgany S (2018). Uber's Mideast rival is hiring women drivers in Saudi Arabia. CNN. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Stancati M (2018). What Saudi women drivers want: Muscle cars. The Wall Street Journal. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Smith-Spark L (2018). The ban on Saudi women driving is ending: Here's what you need to know. CNN. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Stancati M, Abdulaziz D (2018). Saudi women drive toward equality after ban is lifted. The Wall Street Journal. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Takenaga L (2018). For Saudi women, challenges go far beyond driving. The New Times. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

The New York Times (NYT) (1990). Mideast tensions; Saudi women take driver's seat in a rare protest for the right to travel. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

The Washington Post (2013). Saudi Arabia is not driving freedoms forward. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

The World Bank (2020). Women, business, and the law 2020.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Turak N (2018). Saudi women celebrate right to drive, but more work is yet to be done. CNBC. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS) (2018). Saudi Arabia: Education and literacy. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Wirtschafter J, Rifai D (2018). Women in KSA gear up to legally drive for first time this Sunday. USA TODAY. Available at:

View

|

|

|

|

|

Xiang Y, Sarvary M (2007). News consumption and media bias. Marketing science (Providence, R.I.), 26(5):611-628.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Zhang J, Benoit WL (2004). Message strategies of Saudi Arabia's image restoration campaign after 9/11. Public Relations Review 30(2):161-167.

Crossref

|

|