Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

Wetlands are particularly important environmental assets whose sustainability requires meaningful participation of the riparian communities in their management. Yala Wetland is an important resource whose key challenges involve land and water resource use for competing interests which prompted Siaya and Busia County regional Governments to initiate preparation, a Land Use Plan (LUP)/Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) to resolve these. A LUP/SEA Framework with Yala Project Advisory Committee (YPAC) for local communities guided the planning process and implementation. Concurrently, an action research was conducted to assess the level and effectiveness of Yala Wetland community participation in the SEA/LUP processes and improve the outcomes. Research data was derived from 410 respondents from 60 local community groups, 34 key informant interviews, 187 students and satellite images. The Spectrum of Public Participation Model revealed that wetland communities’ participation was at lower levels (Inform (17%) and Consult (83%) while the measure of effectiveness on 10 indicators were poor (20%) and unsatisfactory (80%) thus not meaningful nor effective. Consequently, Yala Hub Framework was developed, occasioning significant improvements in the final LUP. The study concluded that effective community participation determines and influences effective implementation of decisions made and that increased participation through deliberate intervention will eventually increase the effectiveness of community development and encourage long-term sustainability.

Key words: Yala Hub Framework, community participation, strategic environmental assessment, land use planning, wetland.

INTRODUCTION

Wetlands are one of the world’s most important environmental assets which provide homes for large, diverse biota as well as significant economic, social and cultural benefits related to timber, fisheries, hunting, recreational and tourist activities. Yala Wetland is an important resource shared by Siaya and Busia counties of Kenya. It supports the livelihoods of surrounding communities, including water, papyrus and fisheries,

among others, and provides vital ecosystem services such as purification and storage of water. It also acts as a carbon sink, thus regulating global and local climatic conditions and is internationally recognized as a Key Biodiversity Area that hosts globally and nationally threatened bird, fish and mammal species. The wetland is also an important agricultural asset that has attracted both local farmers and external agricultural interests (EANHS, 2018).

Wetlands constitute an important resource for riparian communities and therefore it is important that they participate in their management. Community participation in natural resource management has evolved from the realization that people living with natural resources should be responsible for their management and benefit from using the resources (Ostrom, 1990; WWF, 2006; Bond, 2006; Lockie and Sonnenfeld, 2008; GoK, 2010a; Hardin, 1968; IUCN, 2009). The Aarhus Convention of 1998 states that citizens must not only have access to information but must also be entitled to participate in decision making and have access to justice in environmental matters (DETR, 2000; Stec et al., 2000). However, participation of local communities in seeking solutions to wetlands resources use remains a grave challenge as managers of participation processes engage in low level consultations that do not empower them to co-manage these resources alongside government agencies mandated to do so (GoK, 2010a; Springate-Baginski et al., 2009; Okello et al., 2009; Olson, 1965). Besides, the dynamics of communities’ participation and their activities on the wetland are not clearly understood despite wetland’s continued degradation in size and value (Dobiesz and Lester, 2009; Dugan, 1993).

The Papyrus Wetlands challenges and public participation

A synthesis of research and policy priorities for papyrus wetlands presented in Wetlands Conference in 2012 concluded that more research on the governance, institutional and socio-economic aspects of papyrus wetlands is needed to assist African governments in dealing with the challenges of conserving wetlands in the face of growing food security needs and climate change (van Dam et al., 2014). The other three priorities identified were the need for: better estimates of the area covered by papyrus wetlands as limited evidence suggest that the loss of papyrus wetlands is rapid in some areas; a better understanding and modelling of the regulating services of papyrus wetlands to support trade-off analysis and improve economic valuation; and, research on papyrus wetlands should include assessment of all ecosystem services so that trade-offs can be determined as the basis for sustainable management strategies (‘wise use’).

In Africa, wetlands degradation is on the increase as wetland ecosystems are relied upon to lessen industrial, urban and agricultural pollution and supply numerous services and resources (Nasongo et al., 2015; Kansiime et al., 2007). Similarly, lack of recognition of the traditional values of these wetlands, desire for modernisation and failure to appreciate their ecological role aggravate their degradation (Maclean et al., 2003; Panayotou, 1994).

Public participation

Public participation has been the focus of many Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) and Strategic Impact Assessment (SEA) studies globally (Doelle and Sinclair, 2005; Hartley and Wood, 2005). This article defines public participation as the process of ensuring that those who have an interest or stake in a decision are involved in making that decision. The many ways that organizations interpret and use the term public participation can be resolved into a range of different types of participation. This range from passive participation, where people are told what is to happen and act out predetermined roles, to self-mobilisation, where people take initiatives largely independent of external institutions. Participation has become a key element in the discussion concerning development particularly in natural resources management (Cooke and Kothari, 2001). Today, the concept is seen as a magic bullet by development agencies who are making participation one, if not the core element of development (Michener, 1998).

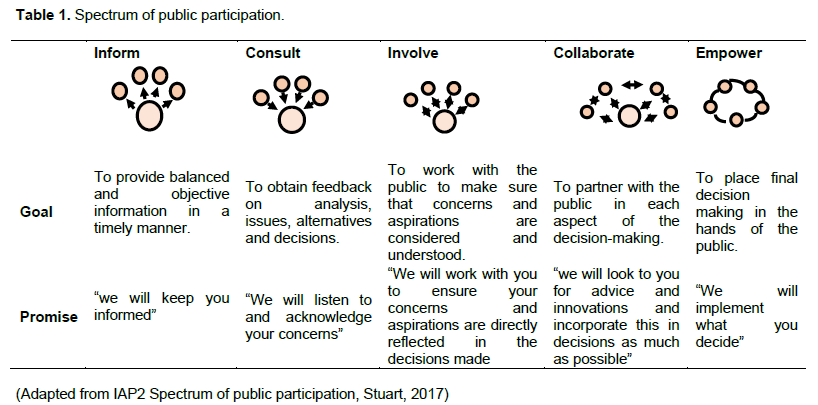

According to the International Association of Public Participation (IAP2, 2008) public participation consists of five levels: Information (lowest level, where participation does not go beyond information provision), consultation, involvement, collaboration and empowerment (highest level, where the public are given a final say on the project decision.

Models and Types of Participation

Participation has been studied and different models offered to show the levels and challenges therein. The models include the ladder of citizen participation (Arnstein, 1969) which show the hierarchies of participation from non-participation, to tokenism and to citizen power with meaningful happening at the apex (citizen control); the wheel model with four levels namely inform, consult, participate and empower (Davidson, 1998); and the spectrum model with five levels from inform, consult, involve, collaborate and empower (Stuart, 2017; Gaventa, 2004) and citizen as partners with five levels from Information and transaction, consultation, deliberative involvement, government – led active participation and citizen-led active participation (OECD, 2001).

Spectrum of public participation

The Spectrum of Public Participation was developed by the International Association of Public Participation (IAP2) to help clarify the role of the public (or community) in planning and decision-making, and how much influence the community has over planning or decision-making processes (Stuart, 2017; IAP2, 2008; Gaventa, 2004). It identifies five levels of public participation (or community engagement) from inform, consult, involve, collaborate and empower shown in Table 1.

The further to the right on the Spectrum, the more influence the community has over decisions, and each level can be appropriate depending on the context. It is important to recognize they are levels, not steps. For each level it articulates the public participation goal and the promise to the public. The first level the Inform level of public participation does not actually provide the opportunity for public participation at all, but rather provides the public with the information they need to understand the agency decision-making process. Some practitioners suggest that the Inform level should be placed across the Spectrum (e.g. above or below it) to demonstrate that “effective engagement with stakeholders at all levels on the Spectrum requires a strategic flow of information” (Chappell, 2016). Since Arnstein (1969) proposed a ladder of citizen participation, almost 50 years ago (ranging from manipulation and therapy, to delegated power and citizen control) there have been several attempts to classify levels of community engagement. The Spectrum of Public Participation is one of the best attempts so far (Stuart, 2017).This study therefore uses Spectrum of public participation to assess the level of community participation in Yala SEA/LUP processes.

White’s (1996) work on the forms and functions of participation distinguish four forms of participation: nominal, instrumental, representative and transformative. She reasons that each form has different functions, and argues actors ‘at the top’ (more powerful) and ‘at the grass roots’ (less powerful) have different perceptions of and interests in each form. Nominal participation is often used by more powerful actors to give legitimacy to development plans. Instrumental participation sees community participation being used as a means towards a stated end – often the efficient use of the skills and knowledge of community members in project implementation. Representative participation involves giving community members a voice in the decision-making and implementation process of projects or policies that affect them. Transformative participation results in the empowerment of those involved, and as a result alter the structures and institutions that lead to marginalization and exclusion.

White’s work helps us to think about the politics of participation (hidden agendas and the dynamic relationships between more and less powerful actors). It is only in ‘transformative participation’ that the power holders are in solidarity with the less powerful to take actions and shape decisions. White emphasizes that this framework needs to be seen as something dynamic, and that a single intervention can include more than one form of participation. One type of participation may not in itself be ‘better’ than another. Different types of public participation are appropriate in different situations, with different objectives and with different stakeholders. Some stakeholders have a greater right to more control of the process than others, some have greater capacity to participate than others and some are quite happy to participate less in some decisions- allowing others such as representative organizations or politicians to take decisions for them.

Emerging lessons and good practices of public participation

From these six project areas carried out in Participation in Planning Water management options, European Union (EU) life environment wise use of flood plain project notes the following six early lessons as emerging on when to do participation (Harrison et al., 2001):

1. Scale: Participation exercises have taken place at a variety of scales with some areas involving communities to consider issues at river catchment level whilst others have broken down into sub catchments or even more local areas along the catchment. Catchment level discussions have generally taken place more with organizations than with individual members of the community.

2. Context: Always the degree to which participation has been successful in involving people, getting views, or even aiming at consensus, has depended greatly on issues of context. These include political contexts, employment contexts, issues contexts, such as flooding, water quality and on cultural contexts relating to a history or not of co-operation and participation.

3. Transferability: Many of the methods including mapping, surveys, timelines etc have been used in the WUF project areas and the experience has been valuable to test different techniques for different issues and with different stakeholders. Flexibility of using techniques is essential and so it is important to have a wide range of techniques. Techniques are transferable but need to be applied and adapted to local circumstances.

4. Training/ capacity/resources: Participation can be resource hungry though some areas have saved costs through using local networks and facilities. The main resource investment is usually time. Techniques for participation vary and the more complex ones need careful training and professional implementation.

5. Processes of participation – early involvement of communities in the decision making process has led to gradual decision making and planning and helped achieve consensus amongst stakeholders.

6. Partnership working – using local host organizations can not only save time and money but also help build up trust and ongoing relationships – especially in cross border situations if the host has a history of cross border working.

Effectiveness of public participation using emerging lessons and World Bank indicators

From the application of participatory approaches in various projects and subsequent emerging lessons and the World Bank public participation lessons (World Bank, 1998:2002, Harrison et al. 2001) some 10 indicators have been identified as key in evaluating public participation effectiveness namely:

1. Objectives – why do participation? what are the objectives – this is a vital reference point for evaluation. 2. Contexts for the participation – helps evaluation. Was participation, for example, part of a larger strategy. political contexts, economic.

3. Levels of Involvement – all to do with how early you involve people, how much power is handed over and when.

4. Who was involved, how chosen – mistakes made (by who?)

5. What methods were used, maps, interviews etc. – did they work?

6. Innovation –of method or just participation itself for the area

7. Commitment – to use or not?

8. Inputs – time, money etc. and results in relation to those inputs

9. Outputs, hard outputs, reports, posters, press, completed survey forms

10. Outcome – most important culmination of the evaluation.

The indicators point at different elements of public participation and this study will use the 10 indicators as well as spectrum of public participation to evaluate community participation framework of Yala Land Use Planning. The synergy of the two methods would help bring the best of each other as well as complement each where they have weaknesses. The World Bank's Internal Learning Group on Participatory Development conducted a study in 1994 to measure the benefits and costs of their participatory projects. A total of 42 participatory projects were analyzed and compared with equivalents. The principal benefits were found to be increased uptake of services; decreased operational costs; increased rate of return; and increased incomes of stakeholders. But it was also found that the absolute costs of participation were greater, though these were offset by benefits: the total staff time in the design phase (42 projects) was 10-15% more than non-participatory projects; and the total staff time for supervision was 60% more than non-participatory projects (loaded at front end). It is increasingly clear that if the process is sufficiently interactive, then benefits can arise both within local communities and for external agencies and their professional staff.

Okello et al. (2009) study on public participation in SEA in Kenya concludes that it was unsatisfactory. The study noted that Environmental Management and Coordination Act (EMCA) of 1999 and its 2015 amendment and Environmental Impact Assessment Audit Regulations 2003 (EIAAR) did not have provisions detailing consultation with the public during SEA and that knowledge and awareness of the public at all levels of society were found to be poor (EMCA, 2015). The undoings of public participation included information inaccessibility in terms of readability and physical access, inadequate awareness of the public on their roles and rights during EIA, incomprehensible language and incomplete regulation for public participation during SEA. Those undoings have to be overcome if public participation in Kenya is to be improved and moved to higher levels (that is, collaboration-empowerment) of participation on the spectrum of public participation level.

Therefore, this study uses cumulatively the 10 indicators to measure the effectiveness of community participation in Yala Wetland Land Use Planning. The synergy of the two methods (spectrum model and 10 Indicators) brought the best of each other as well as complemented each other where they had weaknesses. Thus, Yala Project Advisory Committee (YPAC) framework weaknesses were identified and consequently an addendum to the framework designed to optimize participation of Yala wetland communities in the then ongoing SEA/LUP processes called the Yala RAPPEF-CF-IR Hub framework simply called the Yala Hub Framework. The Yala RAPPEF-CF-IR-Hub is a 5- steps facilitative model used to optimize YPAC framework participation but was also deployed in Siaya County Integrated Development Planning (CIDP) with substantial success Odero, 2021.

Rationale for Effective Community Participation in Yala Wetland SEA and LUP

Yala Wetland is facing many challenges that revolve around land and water resource use for competing interests and also from catchment degradation (GOK, 2018; Odhengo et al., 2018a; Ondere, 2016; Odero, 2015a, 2015b; Muoria et al., 2015; van Heukelom, 2013; Raburu, 2012; Thenya and Ngecu, 2017; Onywere et al., 2011; GOK, 2010b; Kenya Wetland Forum, 2006; Lihanda et al., 2003; Otieno et al., 2001; GOK, 1987). Additionally, the weak frameworks for stakeholder participation especially the local communities in resources management created suspicion and tension among various interest groups in the wetland. These challenges pointed to the need for a well-considered LUP that would provide a rational and scientific basis for future development and use of the resource. This situation prompted and encouraged County Governments of Siaya and Busia, and Nature Kenya to initiate processes that culminated in the present effort to prepare a LUP that will help resolve these challenges so that Yala Wetland will be able to sustainably support local residents’ livelihoods while its ecological integrity and that of its associated ecosystems is protected.

Preliminary processes implemented by Inter-ministerial Technical Committee (IMTC) and a Deltas Management Secretariat prepared a LUP Framework to guide the planning process and was agreed upon by stakeholders. The IMTC’s responsibility is coordination, policy and planning processes of major deltas in Kenya. The Framework was as result of a participatory and collaborative process that involved various stakeholders at the local, county and national levels. As required by Kenya Constitution article 69(1) and part VIII section 87-92 and 115 of County Government Act, 2012 on devolution provisions, and part 2 section 6 (1-2) Public Participation Bill, 2020 provided for participation of local communities in the Yala SEA and LUP process through a Yala Project Advisory Committee (YPAC) (GOK, 2010; GOK, 2012a, b, c and d, GOK, 2020).

This paper seeks to first, determine the level of community participation in the ongoing SEA and LUP processes; second; to determine the effectiveness of community participation in the ongoing Yala Wetland SEA and LUP processes; and, consequently, to develop a framework for optimizing community participation in the ongoing Yala Wetland SEA and LUP processes and Yala Wetland ecosystem management.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The Yala Wetland Area

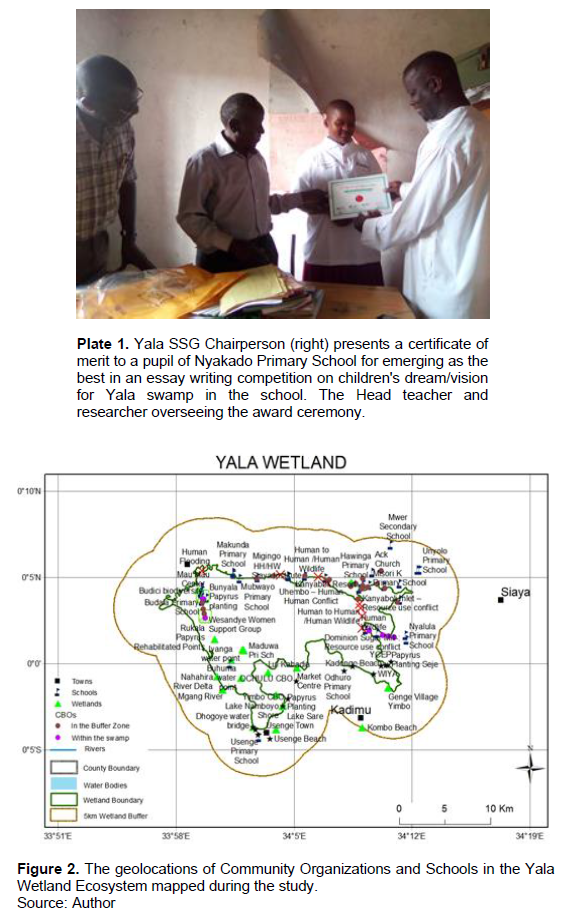

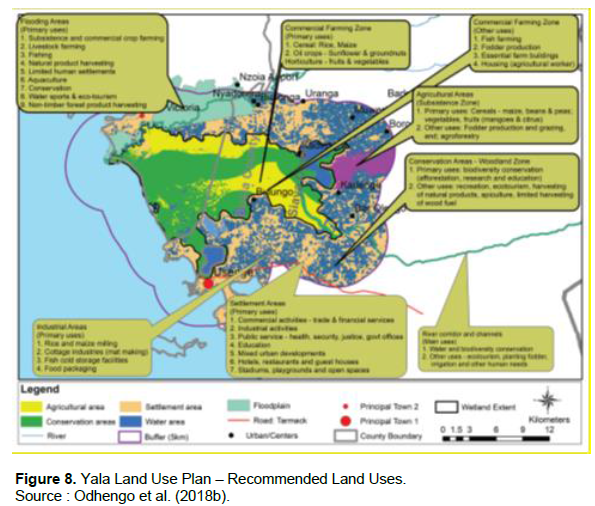

Yala Wetland is located on the North eastern shoreline of Lake Victoria between 33° 50’ E to 34° 25’E longitudes to 0° 7’S to 0° 10’N latitude (Figure 1), and is situated on the deltaic sediments of the confluence of both Nzoia and Yala Rivers where they enter the north-eastern corner of Lake Victoria. It is highly valued by local communities (NEMA, 2016). Yala Wetland is Kenya’s third largest wetland after Lorian Swamp and Tana Delta and has a very delicate ecosystem. It is shared between Siaya and Busia counties of Kenya and covers an area of about 20,756 ha (about 207 Km2) (JICA, 1987; LBDA, 1989; Odhengo et al., 2018b).

Yala Wetland and its environment have a high population density (KNBS, 2009). The Siaya County side had human population density estimated at 393 per Km² in 2009 while Busia County had a higher concentration of up to 527 persons per Km² (KNBS, 2009). Based on the 2019 National Census Results, the population of Siaya and Busia Counties were 743,946 with a growth rate of 1.7% and 833,760 with a growth rate of 3.1% respectively. The population of the planning area (wetland and its buffer of 5km radius) was estimated at 130,838 in 2014 and was projected to be 171,736 in 2030 and 241,280 in 2050 (KNBS, 2009). The mean household size was 5.05, although population density in the wetland and adjacent areas were not uniform. High population concentrations were found in the Busia County side around the banks of Nzoia River and to the South in Siaya County side around Usenge town and north of Lake Kanyaboli (KNBS, 2009). The study focused on the communities inside and within 5km from the wetland boundaries because their propensity to use the wetland is inversely related to travel distance (Abila, 2002). The study also extended to communities living in the upper Yala cluster (lower catchment of river Yala) whose activities affect the Yala Wetland water flow and quality (IWMI, 2014).

Environmental livelihoods of the wetland communities

Yala Wetland has diverse scenic sites that attract visitors from Kenya and beyond. Such attractions include Ramogi Hills, sandy beaches of Usenge, sand dunes around Osieko beach, Oxbow

lakes, migratory birds, and endangered wildlife species among others. Potential tourist attractions in the Yala Wetland include the scenic appeal, bird watching, wildlife viewing, sport fishing, boat riding, outdoor sports and several cultural and traditional ceremonies. However, tourism potential for the area is largely unexploited and poorly developed in the area at present. Muoria et al (2015) estimated that visitors to Yala Swamp contribute Kshs 1,170,200 (USD$1,170.2) annually to the local economy. This is a very low value compared to the estimated potential of Kshs 499,912,500 (USD$ 499,912.5) estimated by Kabubo-Mariara et al (Unpublished data) who used the willingness to pay method (Yala Wetland ICCA, 2020).

Cultural diversity

The communities of Yala Wetland have diverse cultural practices and beliefs, some of which can be exploited for tourism and for conservation. Local communities have strong attachments to the wetland because of their social, cultural and spiritual importance. Some religious or spiritual purposes include baptism, traditional passage rites and ceremonies appeasing evil spirits, cleansing, as shrines etc. The communities also promote indigenous knowledge and practices on environmental functions and values that are essential for their survival such as the use of medicinal herbs. Some villages in the wetland are taken as custodian of clan spirits hence the residents consider it their duty to protect the graves and shrines of their departed clan members (Odero, 2021). However, there is lack of sound documentation and uptake of indigenous knowledge in biodiversity conservation.

Scientific and educational values

The Yala Wetland has immense potential for scientific research, formal and informal education, and training values. The wetland ecosystem is ideal for excursions and fieldwork for learning institutions. The wetland can also serve as important reference areas for monitoring environmental vulnerability such as floods, drought and climate change.

Carbon sequestration

Yala Wetland is among the most effective ecosystems for carbon storage. The Yala wetland vegetation takes up carbon from the atmosphere and converts it into plant biomass during the process of photosynthesis. The Yala wetland therefore is a giant ‘sink’ which is recovering the greenhouse gas, carbon dioxide, from the atmosphere. In many wetlands, waterlogged soil conditions prevent decomposition of the plant material thereby retaining carbon in the form of un-decomposed organic matter (Peat). The long retention of carbon in wetlands prevents excessive amounts of atmospheric carbon, thereby reducing global warming. The retained carbon is easily released into the atmosphere wherever peat lands are drained and exposed to fires. A detailed study of carbon storage in the Yala Wetlands was performed in 2015/2016 (Muoria et al., 2015) and confirmed that the present wetland is storing close to 15 million tonnes of carbon within the papyrus swamp, with less than 1 million tonnes stored in the remaining areas (reclaimed farmland and immature papyrus). This study further revealed that natural and semi-natural papyrus dominated habitats is better carbon sinks than drained farmed areas.

Biodiversity

The Yala Wetland, which is the largest papyrus swamp in the Kenyan portion of Lake Victoria, is an exceptionally rich and diverse ecosystem, containing many rare, vulnerable and endangered species of plants and animals (EANHS, 2018). The wetland is almost entirely covered in stands of papyrus.

Over 30 mammal species have been recorded in the Wetland. They include the Sitatunga (Tragecephalus spekeii), a shy and rare semi-aquatic antelope that is nationally listed as Endangered (Thomas et al., 2016; Wildlife Act, 2013; KWS, 2010). The Wetland provides an important refuge for Lake Victoria cichlid fish, many of which have been exterminated in the main lake by the introduction of the non-native predatory fish, Nile Perch (Lates niloticus). Recent surveys in Lake Kanyaboli recorded 19 fish species within nine families, which included all the two critically endangered cichlids species: Oreochromis esculentus and Oreochromis variabilis (IUCN, 2018; KWS, 2010; Ogutu, 1987a; Ogutu, 1987b). The fishes use the wetland as a breeding ground, nursery, and feeding grounds (Aloo, 2003).

The Yala Wetland climate has a variable rainfall pattern that generally increases from the lake shore to the hinterland (Ekirapa and Kinyanjui, 1987; Awange et al., 2008). The mean annual rainfall ranges from 1050-1160 mm and is bimodal. The mean annual daily maximum and minimum temperatures are 28.9 and 15.9°C respectively – giving a mean annual temperature of 24.4°C (Luedeling, 2011; Semenov, 2008).

The hydrological conditions within the Yala Wetland are characterized by five main water sources namely: inflows from the Yala River, seepage from River Nzoia, flooding from both rivers, backflow from Lake Victoria, local rainfall and lakes within Yala Wetland (Okungu and Sangale, 2003). River Yala is the main source of water for the wetland and other satellite lakes. The naturalized mean monthly discharge is 41.1 m3/s. The lowest flows barely fall under 5m3 /s in the months of January to March while the highest discharge of 300 m3/s occur in the months of April/May and August/ September. The minimum suspended silt load of River Yala Water is 543 ppm (BirdLife, 2018; Sangale et al., 2012; Okungu and Sangale, 2003).

Originally, the Yala River flowed through the eastern wetland (now ‘reclaimed’) into Lake Kanyaboli, then into the main wetland, and finally into Lake Victoria via a small gulf. The Yala flow is now diverted directly into the main wetland, and a silt-clay dike cuts off Lake Kanyaboli, which receives its water from the surrounding catchment and through back-seepage from the wetland. A culvert across the confluence of the Yala, some metres above the level of Lake Victoria, has cut off the gulf on the lake and, through back-flooding, created Lake Sare (BirdLife, 2018; Gichuki et al., 2005). This river flows on a very shallow gradient through small wetlands and saturated ground over its last 30 km before entering Lake Victoria through its own delta. The soils in this region have a very high clay content which impedes ground water flow but there is known to be a gradual movement of seepage water into the northern fringes of the Wetland. Flooding occurs annually and the very high discharge rates mean that the river channels are overtopped with floodwater passing into Yala Wetland. Parts of the western wetland lie below the level of Lake Victoria and are constantly filled with backflow in addition to being subjected to flooding from the lake and upper catchment. Annual rainfall in Lake Victoria Basin (LVB) encompasses a bimodal pattern. The Yala/ Nzoia catchment has high precipitation in the Northern highland (1,800-2,000 mm per annum) and low in the South-Western lowlands (800-1,600 mm per annum). Local rainfall contributes to Yala Wetland water. The water balance for Yala Wetland also includes the water retained within the three freshwater lakes found within the wetland: Kanyaboli (10.5 km2), Sare (5 km2) and Namboyo (1 km2). Lake Kanyaboli has a catchment area of 175 km2 and a mean depth of 3 metres. Lake Sare is an average of 5 m deep and Lake Namboyo has a depth of between 10 to 15 m (NEMA, 2016; Owiyo et al., 2014; Dominion Farms, 2003; Envertek Africa Consult Limited, 2015).

Action research design

Given the nature of the Yala wetland “wicked problems”, action research was the best methodology to unravel participation issues therein. Action research methodologies would assist the “actor” in improving and/or refining his or her actions (Stringer, 1999; Mills, 2000). Also, it seeks transformative change through the simultaneous process of taking action and doing research, which are linked together by critical reflection (Lewin, 1946; Johnson, 1976). Thus, action research is problem centered, client centered, and action oriented. It involves the client system in a diagnostic, active-learning, problem-finding and problem-solving process. The research was done under the regulations and guidance of School of Environmental Studies who subjected the study through its internal review processes and enriched the final outcome-The Yala Hub Framework. The study permit was obtained from the Kenya National Commission for Science, Technology and Innovation.

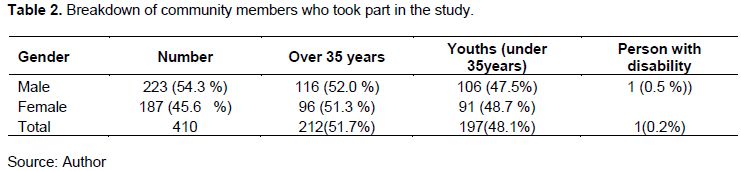

Sampling and data collection

The study used non- random purposive and stratified sampling to collect data. A total of 410 respondents from 60 local community groups participated in focus group discussions (FGDs) from the swamp and adjacent buffer zones (Table 2). The target organizations that were actively involved in wetland conservation within the last five years; have been affected in one way of the other with projects within Yala Wetland, have been a member of an interest group during a LUP/SEA studies in Yala Wetland, have been involved in research and training in in Environmental conservation, EIA or SEA. The community organizations included beach management units (BMUs), Environmental Conservation groups (Yala Swamp conservancy organization, Environmental volunteers), women groups (Nyiego,), youth groups (Hawinga Boda

Boda, smallholder farmer’s cooperatives, Weavers Umbrella group, Lake Kanyaboli Nurseries, religious leaders’ associations, sand harvesters, Yala Swamp Site Support (YSSG), YPAC members.

The 60 community organizations were drawn from all the sublocations/ wards of Yala wetland and buffer zones. Each community organization had only one group of 10 persons participating in FGD irrespective of the total membership. The community organizations membership ranged between 8-60 persons with mixed economic abilities but drawn by the mission and ideals of the specific group. The age of members ranged between 15-85 years while the youngest organizations were five years while the oldest was 30 years old. The 10 respondents invited to participate in the FDGs were chosen to represent diversity within the group and the FGDs were held in convenient locations for local communities. The respondents were mainly group members, active and retired civil servants, teachers, retired teachers, respectable elders who were deemed as custodian of communities’ information and religious leaders.

The FGDs are very advantageous, as Natasha et al. (2005) maintain since they allow collecting substantial data from many people within a very short period. The structure of these FGDs was kept to a minimum, allowing feelings and characterizations to emerge from the participants themselves (Dawson et al., 1993; Krueger and Casey, 2009) on background information about the wetland, their opinions, ideas, perceptions, and beliefs and experiences that influenced their interactions in the wetland and their involvement in its management over the years (Likert,1932). Data were recorded both by written notes and video recordings.

Key informant interviews with 34 highly respected elders and change makers from Usenge, Usigu, Kombo, Hawinga, Uhembo, Bunyala were conducted between April and June 2016. The elders were considered by communities as custodians of the Yala Wetland historical, cultural and indigenous knowledge information. Information received was corroborated with other literature on Yala Wetland to provide historical and contextual information. These informants included deputy chairperson of the Luo Council of Elders from Yimbo, an elder who had also established a Yala community museum in Kombo beach at the shores of Lake Kanyaboli; an elder from Misori Kaugagi; an elder and a youth from Bunyala islands. They narrated the history of the wetland, significant events and trends and their implications. These interviews were video recorded and later used for analysis of the research data and the identity of respondents is concealed in the findings. At the end of each interview session and end of the day the researcher set aside time to record research activities for the day, his observations and experiences for the day and critical reflection in the researcher’s journal (Deveskog, 2013; Greene, 1995; Leggio, 1995). Leggio (1995) in her PhD dissertation titled Magic wand notes: In the last decade, I made some major transitions in my life and the process of writing has helped me think through some of the decisions involved. Writing is a powerful way to create one’s life as well as to record and reflect on it (p.82.).

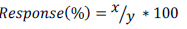

Data were also collected from 187 students who participated through essays writing, debates, poems and artistic works on the Yala Wetland issues and were rewarded for outstanding performance as shown in Plate 1. These were drawn from primary (12), secondary (5) and post- secondary polytechnics and colleges (2) in Yala wetland and its buffer zone. The data were part of what the modified community participation Yala community participation framework brought to the SEA/LUP processes. The qualitative data require triangulation and the data from the learning institutions helped with triangulation as well as bringing students’ perspectives to the study.

Sample size determination for this research was based on judgment with respect to the quality of information desired and the respondents’ availability that fit the selection criteria of active involvement in Yala swamp conservation activities (Sandelowski, 1995). According to Neuman (1997) it is acceptable to use judgment in non-random purposive sampling and reiterates that there is no ‘magic number’. Thus, the 410 community respondents, 34 key informants and 187 students were representative of the wetland communities who were actively involved its management (Figure 2).

Data analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed in using content analysis methods. Content analysis technique allowed the researcher to categorize and code the collected information based on participants’ responses to each question or major themes that emerged from FGDs, in-depth interviews, essays, debates and artworks. Content analysis as Babbie (2015) argues is useful since it captures well the content of communications generated through interviews, essays and FGDs in an inductive manner, where themes were generated based on emerging similarities of expression in the data material. Many of these elements provided quotations in the write-up of research findings and other similar elements were quantified using descriptive statistics to give a sense of the emerging themes and their relative importance according to the respondents. Priority ranking of issues was done to arrive at overall prioritization of issues by wetland communities that informed the final LUP content. The study dealt more with people’s perception than with statistically quantifiable outputs. Thus, data analysis to gauge these perceptions was done by calculating percentage response (Neuman, 1997). The response rates were calculated using the following formula.

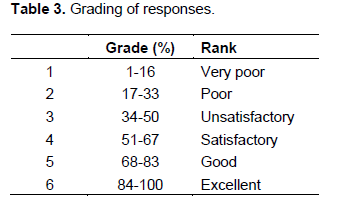

Where x: respondent groups who gave feedback and y total number of respondent groups. To grade the percentage response, a modification of Lee’s (2000) EIA study review package was used (Table 3).

Schools essays, debates and artwork analysis

A select team of panelists that adjudicated the learning institutions entries comprised the Researcher, one Research Supervisor from

SES, Program Manager from Nature Kenya), Research Assistant from SES and Siaya County Director of Education. Each panelist marked the 187 essays and art works, guided by the following parameters: background information, context, creativity, vision and

dream all seen as identification of appropriate key challenges of the Yala Wetland and prescription of potential solutions that address the identified challenges with the potential highest score being forty marks. These parameters were based on the issues that SEA and LUP were investigating to inform the development of Yala Wetland LUP and ecosystem management starting with the vision of Yala LUP, understanding the contextual and historical information about the wetland and finally key environmental issues and what actions are required to ensure sustainable management of the Yala ecosystem. Table 4 shows the adjudication criteria for students’ submissions.

The individual panelist scores were recorded and the average score tabulated to arrive at the overall score for the entries. The top 3 students from every school were awarded prizes as well as participating institutions. The essays school entries were further analyzed using content analysis to itemize environmental issues, desired future and strategies for attaining that future for inclusion in the final SEA and LUP outcomes. Satellite images from Google Earth provided detailed photographic evidence of the condition of Yala Wetland and its various land use changes over years. These satellite images also helped to determine the current size of the wetland in line with revised definition of the wetland in EMCA 2015. Satellite images and GIS analysis were used variously to determine land cover/land use changes (EMCA, 2015; Turner, 1998; Liverman et al., 1998; Chambers, 2006; Ampofo et al., 2015; Lillesand and Kiefer, 1987).

Literature review was conducted on public participation, policies, laws and relevant studies that provided secondary data and a valuable source of additional information for triangulation of data generated by other means during the research and this has also been used by many researchers (Friis-Hansen and Duveskog, 2012; IYSLP, 2017).

Overall, a multidisciplinary research using case study design employed exploratory action research with both qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection and analysis. Appreciative Inquiry (AI) methodology and participatory approaches and secondary data were used in data collection and analysis (Dweck, 2008; Cooperrider and Leslie, 2006). The secondary data include policy and legal frameworks, wetland ecosystem management guidelines and procedures, relevant studies to Yala wetland and other sensitive ecosystems elsewhere. This qualitative research was supported by quantitative methods on how contextual factors and processes affected the planning and management of Yala wetland ecosystem. Corbin and Strauss (1990) noted that quantitative and qualitative methods are tools that complement each other, while Greene (1995) in her doctoral research demonstrated the value of journaling as research methodology for in-depth reflection by the researcher and vital in action research designs. Greene (1995) says “learning to write is a matter of learning to shatter the silences, of making meaning, of learning to learn” (p.108).

The Yala project advisory committee

YPAC was the main mechanism for representing the communities of the Yala Wetland in the Yala LUP whose role was to discuss the findings of the SEA and LUP processes and content and obtain views from the wetland communities. The YPAC members were tasked to guide and instruct their own communities on the role and purpose of the LUP and SEA; to provide effective communication vertically and horizontally; to minimize misinformation and were collectively responsible for common good.

YPAC consisted of 46 members drawn from local communities and reported to the Inter-County Technical Committee (ICTC). The YPAC organ represented various interests namely ecotourism, cultural groupings/heritage; conservation; religion; islanders; fisherman; hunters; persons with disability, transporters; handicraft; farmers; investors; wildlife (honorary warden); county technical officers (lands, livestock, water, fisheries, crops, forests); sand harvesters; the youth; administration (ward, sub-county); and voluntary scout.The National Government and the County Government officers participated in YPAC meetings as observers and adjudicated on any internal disagreements.

RESULTS

Assessment of Yala Project Advisory Committee (YPAC) Framework

During the period of LUP development, YPAC held over six meetings. The main challenge of YPAC’s members was how to report back the deliberations and seek inputs from a large number of their constituencies (e.g. some over 200 persons). As a result of logistical constraints, they presented their own views and received inputs from only those around them. This offered limited local community participation. Similarly, they were unable to seek broader view of their representation to enrich YPAC meetings and feedback to draft SEA and LUP reports thereby limiting the quality of community participation in SEA and LUP development. Thus, YPAC framework membership was narrow with respect to representation and quality given the entire spatial area of wetland and its buffer zone. Additionally, the YPAC members had inadequate logistics and skills required to undertake their roles and responsibilities.

Assessing the level of community participation in SEA/LUP process using spectrum of public participation model

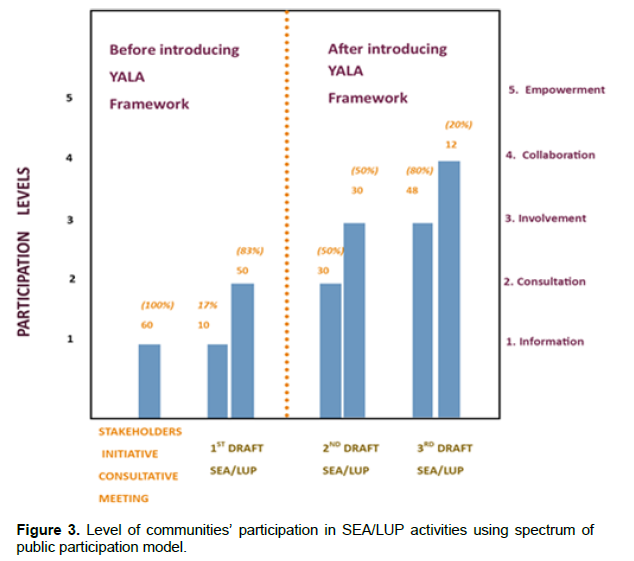

The level of community participation in SEA/LUP using Spectrum of Public Participation Model was at low levels (draft 1 SEA/LUP “Inform (17%) and Consult (83%) levels. But, the application of the Yala Community Participation framework (The Yala Hub Framework) significantly improved community participation (draft 2 SEA/LUP Consult (50%) and Involve (50%)” and draft 3 SEA/LUP at (Involve level (80%) and Collaboration level (20%). Figure 3 show the levels of communities’

involvement in various SEA/LUP processes and various drafts of the plan.

DISCUSSION

With application of Yala Community participation framework in the existing YPAC framework with its identified weaknesses, the wetland communities felt that the process ensured their concerns and aspirations were therefore directly reflected in SEA and LUP and that together with the Government they would implement the resultant LUP recommendations.

Thus, the Yala Hub Framework was an optimizer for community participation in the LUP development that understood the Yala wetland context to enhance their participation. This finding is supported by best practices in public participation that noted the need to overcome personal and institutional barriers to public participation, understanding context (political contexts, employment contexts, issues contexts, such as flooding and on cultural contexts relating to a history of co-operation and participation (Harrison et al, 2001,GOK, 2020).

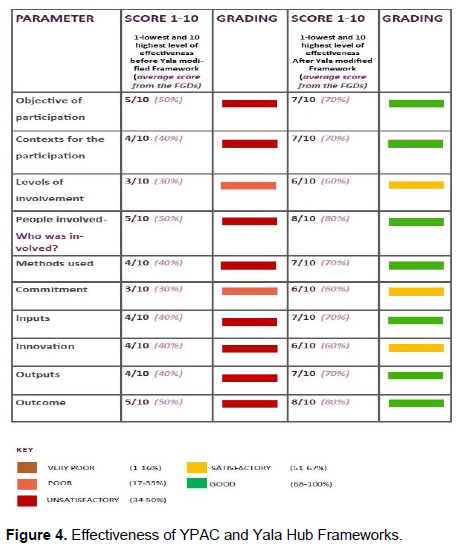

Assessing effectiveness of communities’ participation in SEA/LUP processes using 10 indicators for public participation

The Community participation in SEA/LUP processes were evaluated for effectiveness using the 10 Indicators for public participation effectiveness. The results of effectiveness with the original YPAC participation framework and the results after the application of the Yala Hub framework. The results reveal communities’ participation effectiveness in SEA/LUP was poor (2 indicators) and unsatisfactory (8 indicators) with YPAC. However, with the application of Yala Hub framework, the effectiveness moved to satisfactory (3 indicators) and good (7 indicators) as shown in Figure 4. The results also show that YPAC framework was poor in levels of involvement of people (30%) and commitment to community participation (30%).The overall score on YPAC effectiveness was 41% (unsatisfactory) but this moved 68% (good) with the application of Yala Hub framework. There was a shift in all 10 indicators with introduction of the Yala Hub framework towards greater satisfaction. Thus, Yala Hub Framework enhanced

effectiveness of the Yala wetland community participation in SEA and LUP processes and outcomes.

This is further confirmed with spectrum of participation at inform and consult levels in draft 1 SEA and LUP reports. Yet, early people involvement and commitment are key to the outcome of the participation process. These weaknesses had to be rectified very urgently if the process was to achieve desired outcome with the communities’ meaningful participation. Thus, another mechanism to specifically deal with these weaknesses was required thus paving way for the improved Yala Community Participation framework. This result shows that community participation in LUP and SEA processes is ‘alive’ process that requires constant checking and modification to respond to the emerging issues on the content of the plan and the community involvement processes in the plan development.

The assessment level of community participation using Spectrum of Public Participation Model and the effectiveness using 10 Indicators of Public Participation show that YPAC framework was poor and unsatisfactory in providing meaningful participation for communities in the development of Yala wetland land use and ecosystem management plan. Likewise, the analysis revealed the need to use different models which triangulate the information but also complement each other for any model’s inherent weakness. Thus, a combination of Spectrum of Public Participation Model and 10 Indicators of Public Participation effectiveness was good for Yala wetland ecosystem management context. The areas of underperformance based on these assessments are the basis for an improved community

participation framework presented in below.

The Limitations and challenges of YPAC Framework-the rationale for designing an addendum mechanism to Optimize Community Participation

The results revealed strengths and challenges of the YPAC participation framework which needed to be addressed to ensure effective community participation in Yala LUP. The limitations and challenges of YPAC included narrow YPAC membership, quality of participation concerns by YPAC members (capacity issues); inadequate points of community participation 6 out of 11 steps in LUP process (2, 4, 5, 7, 9 and 10);

low level of community involvement (spectrum levels); unsatisfactory participation (10 indicators evaluation results); challenge of communicating scientific and technical information to communities; dominant fixed and negative mindsets about the wetland; lack of methodology for integration of indigenous knowledge with scientific information; disconnect between the wetland decision making and provision of adequate scientific and technical evidence/or information; absence of governance framework with communities strong representation; lack of transformational and value driven leadership at the community level, and absence of comprehensive wetland wide information system (rather ad hoc and scattered pieces of data and information). These 12 limitations as an outcome of the analysis of SEA and LUP processes compromised the ability of YPAC to represent wetland communities meaningfully and effectively in SEA/LUP process, thus the basis for designing framework to optimize the given framework.

The Yala RAPPEF-CF-IR-Hub framework (The Yala Hub framework)

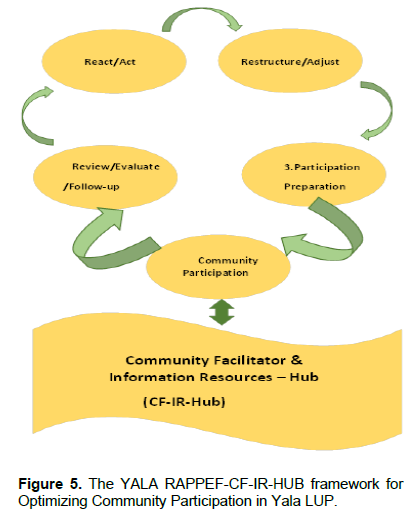

This is a framework designed to optimize community participation in Yala Wetland planning and ecosystem management. The framework sought to remedy the weaknesses of the original YPAC mechanism as well as tap opportunities presented as an outcome of the action research. The framework is called Yala RAPPEF-CF-IR Hub Framework based on the various steps on using it and shall be referred to in short form as the Yala Hub Community Framework. The five steps are 1. React/Act. 2. Restructure/Adjust the participation framework based on the reactions. 3. Participation Preparations. 4. Community Participation and 5: Review, Evaluate and Follow-up and these are supported by a base of a Community Facilitator (CF) with a supportive Information Resources Hub (IR-Hub) to support its execution as presented in Figure 5. The details of how this framework works are discussed subsequently.

Step 1: React/Act.

The first thing is to gain entry to participate in the process with a high degree of acceptance if the process is already ongoing. The intervener has to find appropriate entry point which depends on the context and how the facilitator positions self (e.g. researcher with their interest at heart, their own representative with technical expertise in the process, known conservationist of good reputation with community) and also application of emotional intelligence to penetrate the ongoing process (e.g. understand their areas of greatest need to participate in the process).

If the process is starting, then conduct stakeholder analysis to check on representation particularly of the local wetland communities. If it is in progress then conduct stakeholder analysis tier two, which reviews existing stakeholders and their level of participation, and special preference for local communities. The key guiding question is how effective the processes in representing the local communities (their interests, sharing wetland accrued benefits).

The guiding questions for this step are:

1. What does this community regard highly that can lead to high degree of acceptance of an outsider/ a facilitator?

2. Who is participating in this process? Who is missing on the decision-making table? Which other important voices are not being heard on this planning agenda? Are the divergent voices included in this process? Does participation ensure fair geographic representation? The process facilitator should identify these and ensure their inclusion.

3. What are the strengths and challenges of the existing community participation framework currently being implemented? In the three phases baseline, scenario building and alternative land use options and preparation of final plan; the 11-steps SEA/LUP processes and on spectrum of public participation (informing, consulting, involving, collaborating to empowering levels).

4. Using the 10 indicators for public participation effectiveness, what are strengths and weaknesses of the current community participation framework in the SEA and LUP processes? How do you ensure the weaknesses are mitigated going forward? The 10 indicators are Objective of participation; Contexts for the participation; Levels of Involvement; Who was involved, how were they chosen and by who? What methods were used (maps, interviews), if they did, they work? Innovation of the methods used; Commitment to community participation; Inputs (time, money etc. and results in relation to those inputs); Outputs (hard outputs, reports, posters, press, completed survey forms); and Outcome.

Step 2: Restructure/adjust the participation framework based on the feedback step

The outcome of step one forms the basis for adjustment and restructuring at this stage. In the SEA and LUP processes the researcher adjusted the participation process by bringing to the decision-making table very important stakeholders who were not initially left out. It expanded the representation of local communities to include community formations/organizations and learning institutions at their bases in addition to YPAC. Both preparations and actual implementation methodologies were modified, and new ones added based on step one feedback. If the project or program is new, then it moves from step 1 to step 3 bypassing step 2.

Guiding questions were:

1. Who needs to be added to the participation processes? What uniqueness do they bring on board?

2. How can one ensure meaningful participation from the people joining an ongoing process (i.e. language, facilitation, logistics and associated costs) without feeling they are joining the process late?

3. How are the elements that were hampering community participation effectiveness being tackled in the adjusted mechanism?

4. How can one use participatory methodologies (like empathy walks) to improve participation?

5. What should one do to improve the environment for participation and harness creativity?

Step 3: Participation preparations

The third step called for thorough preparation before the actual participation. Consequently, this step evaluated participation readiness and ensured the process was ready by addressing identified concerns/feedback; identifying facilitator(s) and equipping them to manage the process effectively; practical training on facilitation skills including mock training amongst facilitators; enabling logistical support, and framing issues for discussion with the identified stakeholders in step one using appreciative lenses focusing on root causes and suggesting the possibilities of tackling them.

The guiding questions for this step were:

1. What is the community participation process in this activity? Does the process provide local communities with room to articulate their interests and concerns?

2. What are the units of participation? What is the smallest unit for participation in this case? How are they organized to enable smooth flow of information and receive timely feedback?

3. What type of persons will be required to facilitate this participation process?

4. What type of skills and training are required to equip facilitators of this process?

5. What logistical support and budget will be required to conduct this participation?

6. How does one frame issues for effective discussion with the identified stakeholders in step 1 above?

7. Which participatory methodologies (including empathy walk) and how will one use these in community participation processes?

8. What creativity and innovations will one bring to this community participation process?

Step 4: Community participation

This step is where the wetland communities interact with the planning processes and relay the feedback to the main LUP technical team. Various methods are used for these interactions which enable the communities to express themselves holistically. For example, by empathy walks; consulting in communities’ local languages; artistic works where talented community members express themselves; and cultural artifacts to express themselves. The CF manages the community participation processes using various participatory methodologies and resolves any participation challenges to ensure maximum interaction of communities in the planning process and relaying critical feedback to the technical team and other planning organs outside the formal consultation sessions.

The guiding questions were:

1. How does one conduct community consultations that will allow participation of the new groups to smoothly integrate with other existing teams?

2. Summarize the key issues about (SEA/LUP) process to date? What are the areas of convergence? What are the areas of disagreement? What other concerns about Yala wetland do the wetland communities have?

3. What participation tools are appropriate for the targeted community and why?

4. How are the processes outcomes documented, validated by the communities and relayed to the LUP technical team for inclusion?

5. What do the wetland communities’ value most about the wetland and why? What are the communities’ non- negotiable on the wetland ecosystem resources?

6. Identify sites of environmental significance and conduct empathy walk with communities to pool out their issues /feelings on those sites?

7. Immerse oneself in the community to experience their issues and ensure that the participation process brings out what one has experienced even if not comfortable to talk about?

Step 5: Review, evaluate and follow-up: Participants feedback about participation processes

At this stage stakeholders evaluate the participation processes and outcomes guided by the following questions:

1. Evaluate the community participation process using appreciative enquiry methodologies targeting the key groups involved in the planning process: a. with the wetland communities’ b. with the researchers’ c. with the technical team d. with custodians /County officials from departments of Lands e. with Professionals f. with schools.

a. What went very well? b. What could be done even better/improved next time?

2: How does one feel about the final outcome of Yala Wetland Land Use Plan and ecosystem management plan?

3. What follow-up mechanism is in place to ensure community participation issues /outcomes in the plan are later implemented?

4. How does one get the community as a key player in the implementation processes?

5. How does one ensure that the benefits from Yala wetland are shared equitably with the wetland communities and other key wetland actors with a mutual accountability system?

Community facilitator

At the core of optimizing community participation in SEA and LUP processes is the CF who helps communities navigate those five steps and is supported by an Information Resources Hub (IR-Hub). The Yala RAPPEF-CF-IR-Hub framework is a facilitative model and with the CF being key to its execution. Therefore, a dedicated community facilitator should bring certain attributes to the process that are in synch with the planning context. The attributes that were appropriate for Yala wetland were: skills and capabilities in planning and management; knowledge of environmental sciences; networking and advocacy, proximity and access to decision makers; and, community acceptance to generate a feeling that it was a safe environment of trust and mutual respect.

Effective participation demanded the commitment to implement the plan as the local communities saw themselves as co-creators. The researcher became a CF in wetland planning process thereby provided a link amongst local communities, the SEA/LUP technical team and the Inter-County Steering committee. The expanded community consultations feedback was then presented in YPAC meetings and at various writing stages with IMTC technical specialists by the CF.

The creation of CF in the framework served many practical concerns of the wetland communities. A key feature it provided was a safe environment of trust, inspired confidence and mutual respect for participation. This was further confirmed by top-level leadership respondents’ remarks who told the CF “you are our son please tell us, will our ideas be taken seriously or they will do like what Dominion Farms did”. The CF-IR-Hub component sought to reduce the disconnect between decision makers and provision of scientific and technical information for Yala wetland. The CF had access to the decision makers and was part of the technical team hence would weigh in to provide this nexus.

Among the key framework inputs taken on board in final SEA/LUP documents were: i) Historical and contextual information of Yala swamp (chapter four in SEA report titled understanding characteristics of Yala swamp and its recent history); ii) previous studies on how multipurpose water projects would affect environmental flows of the river Yala and the swamp (i.e. Identification of a Multipurpose Water Resources Development Projects in Gucha-Migori and Yala River Basins in Kenya (2011-2012) where the researcher was part of the team); iii) envisioning the future Yala Wetland and subsequent broader shared ownership of the sustainable Yala wetland vision; iv) creating a sense of urgency on the need to conserve Yala wetland and the role of local communities required to take charge (co-owners of the wetland) in line with the Indigenous Community Conservation Areas (ICCAs) management requirements rather than being bystanders (Davies et al., 2012).

Information resources hub (IR-Hub)

The IR-Hub was vital in gathering, processing and relaying timely data and information required to inform the processes. The information resources gathered included previous related studies on Yala wetland, feedback from community meetings, validation feedback of various SEA/LUP outputs and draft reports; vital networks/contact persons who were called to inform and input the various parts of the process. In the IR-Hub, facilitators used multifaceted but audience appropriate channels in communicating with them. For example, CF relayed technical process outputs through graphical images, community, storytelling, folklores, sayings, proverbs and metaphors. Constant feedback by CF using appropriate target audience information and channel was key in applying the framework. The IR-Hub should be a ‘live’ entity, constantly growing and replenished with current information.

The application of Yala community participation Framework in SEA/LUP process and its outcomes

The framework was applied in the then on-going SEA and LUP and the following discussion show the processes and outcomes.

Important but ignored actors brought to the decision-making table

The second stakeholders’ analysis substantially brought important but initially left out actors in the SEA/LUP process to the table. Consideration here was given to subject matter representation, meaningful geographic representation/spatial spread; the first stakeholder analysis assumptions which did not hold that YPAC would represent the communities and have seamless flow of SEA/LUP information to the local communities; and empathy walk to have a feeling for the community on the Yala Wetland. These eleven additional actors were: the Luo Council of Elders (custodians of communities’ heritage). Schools (nursery schools, primary, secondary and post-secondary) played catalytic role of learning and implementing, ethos for sound management of the wetlands, awareness raising about the Yala wetland sensitivity, envisioning Yala wetland future through essays, debates and artwork). Change makers in the community who brought new planning issues such preservation of herbal trees, land tenure socio-cultural dynamics and how it determines its subsequent care, as one female change maker deeply revealed on gender constraints.

“we cannot obtain land title deeds without the permission of our husbands or male guardians. Communities fear losing their land to strangers from different clans when their women are inherited upon the death of a husband or if a woman remarries from a different clan”

The professionals from the Yala Wetland (experts on land, water, environmental conservation, academia, scientists and researchers) who brought a deeper analysis of the planning issues, lessons learnt and best practices from elsewhere, interrogated drafts and gave their expert views and recommendations; The local administrators (chiefs, sub-chiefs, village elders (mlangos)-(current and retired) were key entry points into the communities as well as resolving communal conflicts besides providing additional historical and contextual information; The Wetland International Eastern Africa office (WI) wetland experts visiting guest in their network from various African countries on a tour of Yala swamp (unique biodiversity value and those ones under threats like globally threatened species which are endemic to the delta ecosystem); The Tourist Association of Kenya on tourism potential of the Yala swamp and its integration within the western Kenya tourism circuit; the small and medium scale investors in Yala swamp on their plans to expand their farm activities and the need to increase water abstracted from Lake Kanyaboli and the wetland. Additional NGOs giving valuable feedback to draft plans; The Motorcycles Association (Boda boda); and the media who covered subsequent process outcomes in their various media channels mainly newspapers, FM radios and documentaries.

Levers for increasing community participation rates

The Yala Hub framework provided events for multi-stakeholder participation and feedback which include Annual Wetland Day Events, World Migratory Birds’ Day and Environment Days. Additionally, schools essay

writing, debates and artworks, organized community meetings at village levels were new avenues for participation that required its own facilitation as discussed below.

Annual wetland and environmental day events

Siaya County Wetland Day of 2016 held in Usenge Primary school had schools who extolled the benefits of the Yala Wetland and the need to preserve it. The event was preceded by a bird watching exercise at Goye cause way with identification of 60 bird species while songs, poems and dramas were used to convey wetland conservation messages. The Yala Hub framework also used the occasion to update the communities on the progress with SEA and LUP and researcher launched the school’s competition titled envisioning the Yala Wetland in 2063 at the event (Plate 2-3).

The 2017 World Wetland’s Day was celebrated in Hawinga Primary school themed:

the importance of world migratory birds where the researchers seized the occasion to discuss the progress of SEA and LUP and then sought community contributions on the same. The results of these participation processes were: strengthening environmental awareness programmes in schools through clubs, tree planting and post planting care, promoting hygienic practices and protection of Lake Kanyaboli and water springs; a deeper understanding on the Yala Wetland challenges and the role of the wetland communities in solving them. Likewise, some of elders gave talks on the values the Yala communities attached to various types of birds and how they then treated them based on these understanding (indigenous knowledge and passing that to school during the event). The structured and goal oriented social interaction/active engagement amongst pupils, parents and guardians and technical staff from the government continued to offer opportunity for cross learning from all the subsets of communities represented. The continued participation of schools inculcated environmental consciousness and subsequent behavior change among the pupils at an early age.

Schools debates and artworks contribution to Yala SEA/LUP

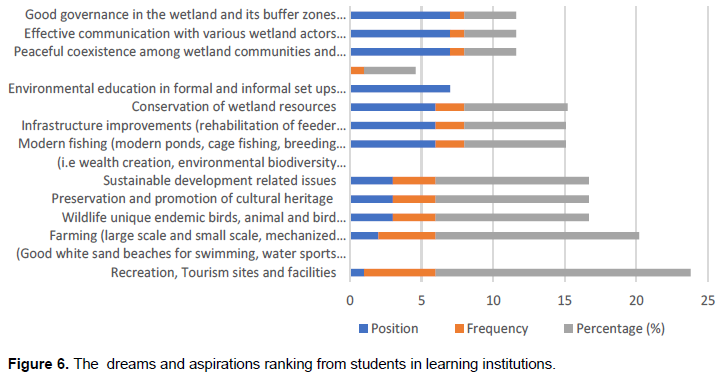

The participation of learning institutions in SEA and LUP that came with the Yala RAPPEF-CF-IR Hub framework which was done through competitions on essay writing, debates and artworks gave the students an opportunity to focus on Yala Wetland and then contribute based on the environmental issues/challenges and their envisioned future which helped in crystalizing the vision of Yala LUP. The results on envisioning priorities are shown in Figure 6 while the artworks were creatively integrated in one mosaic shown in Figure 7.

Community meetings at village levels

Communities’ participation was mostly done through community meetings at village levels facilitated by the researcher and assisted by research assistants and YPAC members. Some were done as focus group discussions for smaller groups; community open forums where researcher explained the purpose of mission, briefing on SEA/LUP status and then discussions guided by the facilitator on key themes SEA/LUP issues. To ensure high level of attendance, wetland residents from relatively far-off places were facilitated with transport and light refreshments during the meetings.

The YPAC members then got the opportunity to meet communities and discussed YPAC issues during those researcher’s facilitated sessions. The process was enriched as they managed to gather from communities on their priority issues using participatory methodology tools. The feedbacks were captured and processed and the researcher feedback (as a new feedback loops) to the technical team in the form of review of drafts and commenting with input from the community. Second, during the meeting with YPAC the various members were able to bring key summaries from these meetings to the LUP technical team which they could not do before the support they got from the application of Yala Hub

framework. Later, the researcher had the opportunity with various subject matter specialists in the technical team and would reach out to them for key inputs for incorporation the plan drafting process (community facilitator secured a place in the technical team to work with them in preparing the LUP).

Targeted sourcing for critical inputs into the SEA/LUP

The communities’ feelings on participation in SEA/LUP based on the Yala RAPPEF-CF-IR-Hub framework were varied. Majority felt that this should have come at the beginning of the LUP process to allow for intense consultations with communities and solicit their critical input to inform the processes.

The pupils and students on their part while expressing gratitude for the involvement; proposed that the competition should be held annually to allow many students to get involved and steer tangible conservation action. Additionally, they suggested that environmental clubs should be actively involved in conservation activities of Yala Wetland and be recognized if they implemented their dreams as captured in the mosaic Figure 7. Furthermore, environmental conservation and education guidelines for lake and river basins and wetland should be developed to guide implementation of these activities. In the guide development, the learners stressed the use of students and young people friendly packaged information and expanding the guide to cover areas brought out in their aspirations, debates and artworks’ submissions.

Community participation requires full time institutional support and commitment - Community Facilitator and Information Resources Hub

The Community Facilitator and Information Resources Hub was designed as the base of the framework to support the communities navigate the five steps processes accounting for 35% of its improved framework effectiveness.

Community facilitators

The Community Facilitator (as the researcher) formed a team and networks to enhance community participation in SEA/LUP processes. The team consisted of Research Assistants from School of Environmental Studies, University of Eldoret (for technical know-how); some members of Project Advisory Committee and Yala Site Support Group (YSSG) (for local knowledge, acceptance by community and community level meeting facilitation) and linkage with networks of professionals from and/ or with interest in Yala Wetland (technical expertise and genuine involvement in determining the development paths of their communities); Development Facilitators and partners to allow for navigation into the processes without hindrances (Nature Kenya, The IMTC and County Government Leadership). Thus, relationship building was vital aspect of increasing community participation and the Community Facilitator brought in this aspect by building a safe environment of trust, inspired confidence and mutual respect for participation.

The type of stakeholders targeted determined the type data collection tool adopted. For example, the youth preferred a mix of media at the same time (audiovisuals, social media whatsapp, facebook, instagram, group work sent to their phones directly), while in schools the team opted for artwork, debates, essays with queries that focused on challenges and what future they envisioned of the future Yala Wetland, for environmental events days the team choose gallery walks on artistic works display of Yala Wetland, wetland products display, live performances like poems and dramas with conservation messages, display of ecotourism sites and thematic songs delivered with aid of traditional instruments (such nyatiti, ohangla, orutu, pekee, tung) and talks by both government and community leaders based on the theme of the event. The CF also seized those occasions to update wetland communities on SEA/LUP progress, key planning issues and obtained their feedback on the updates.

In addition, the steps intentionally involved the use of local leaders to co-facilitate the meetings with the researchers after being trained on SEA/LUP specific issues. This gave them the opportunity to relay SEA/LUP updates from Inter-county steering committee and technical team, which had been a challenge before. Each team was also provided with latest copies of SEA and LUP and YPAC meeting minutes to equip them while conducting community meetings.

The CF became a lever for increasing participation rates and new feedback loop for the SEA/LUP processes. Consequently, to perform these functions, the CF needed to be somebody whom they respected, trusted and had the power to engage at main stages and structures of SEA/LUP processes (ICSC, YPAC, Technical team, Learning and Research institutions, various players of policymakers). The CF brought certain attributes to the process that were harmonious with Yala wetland context. The skills and capabilities in planning and management; environmental sciences knowledge; networking and advocacy, proximity and access to decision makers and community acceptance.

Information resources Hub for accessing relevant information to make informed decisions that is evidence and outcome based

There was a gap of Yala Wetland Information System to collate existing relevant information, information generated by the SEA/LUP studies and processes; and others to increase the quality of community participation in managing Yala Wetland ecosystem. During the process the SEA/LUP secretariat and the researcher carried out some of those tasks. The information resources gathered related to studies on Yala swamp, feedback from community meetings, validation feedback of various SEA/LUP outputs and draft reports; vital networks or contact to review the various parts of the process. For example, CF relayed technical process outputs to the wetland communities through graphical images, storytelling, folklores, sayings, proverbs and metaphors. In repackaging technical information, the communities required less text and tables but rather more visuals, graphics and intuitive information delivered mostly in consultative and experiential processes with adequate time for questioning, reflection and responding. Therefore, IR-Hub enabled communities and their agents to access relevant, timely and repackaged information to facilitate their participation in SEA/LUP processes. The IR-Hub operations thus entailed sourcing, processing, repackaging, storing, retrieving, targeted dissemination, and receiving and acting on feedback. In the IR-Hub, facilitators used multiple audience appropriate channels in communicating with them. Also, there were constant feedback by CF using appropriate target audience information and channel.

On framing issues, the team used appreciative words, that is, positive, optimistic and desired result focus to guide the information gathering for some respondents. For community organizations to elicit feedback, the researcher framed guiding questions for each category.

For the students, the essay topic was “what is your dream for the future of Yala Wetland in 50 years’ time if money is not a problem?; the religious leaders, they were asked to reflect with their leadership teams and thereafter prepare a compelling God inspired sermon on the theme of a better Yala Wetland; and the professionals, they were asked to give back to their communities their expertise in developing the Yala wetland land use plan, to which some responded by reviewing the SEA/LUP drafts.

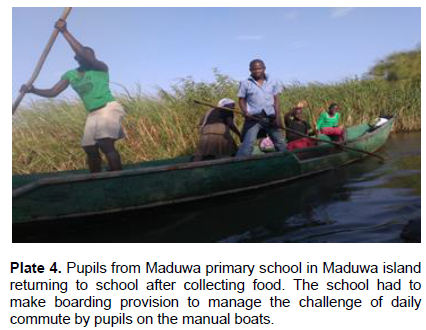

The researchers used empathy walks shown in Plate 5 as he moved into the Yala Wetland with inhabitants who narrated their issues (e.g. an elderly woman showing the graveyard of her husband and reasserting her unwillingness to leave the grave in Yala Wetland if the residents are to be relocated; mini-boarding school in the swamp where pupils return home over the weekends to replenish food supplies (Plate 4) and in those situations researchers just engaged in deep listening to derive deeper meanings which they reflected in their journals allowing new forms of information to flow into the process and was key in designing the logical steps of the Yala RAPPEF-CF-IR Hub framework. Therefore, the IR-Hub became a ‘live’ entity, constantly growing and replenished with current information.