ABSTRACT

Despite the role that rural women in Nigeria play in protecting the environment, not many studies acknowledge their contributions. As part of efforts to highlight women’s contributions, this study interviewed 60 women between the ages of 20 to 60 on how important the environment is to their livelihood and how they protect it. Fifty percent (50%) of the women identified as farmers, forty percent (40%) as traders, three percent (3%) as housewives and seven percent (7%) identified as public servants. The participants reported that their activity under those capacities makes them interact closely with the environment; at different levels though. As part of efforts to protect their environment, these women engage in activities such as tree planting, manure application, sustainable harvesting and environmental sanitation as ways to give back to the environment. In their bid to protect their environment, the women face challenges such as poverty, cultural barriers, and the lack of government support. Policy makers are called upon to acknowledge the role of rural women in protecting the environment and include them in programmes surrounding conservation, disaster management, awareness campaign and rural development.

Key words: Environment, women, rural, protection.

Women, especially in developing countries are said to work more closely with their environment because in most cases they rely on the environment for their subsistence (Glazbrook, 2011). Their interaction with the environment could be in form of subsistence farming, cleaning, or other activities that form part of their domestic responsibilities. In most Nigerian rural communities, women are primarily responsible for managing domestic affairs; this could range from cooking meals, cleaning the house and surroundings, caring for children and the elderly, gathering of firewood and wild food harvesting (Wuyep et al.,2014). While carryingout these activities under different capacities (housewives, traders, farmers), these women are said to have a close interaction with their environment and engage in various practices that are sustaining and protective of the environment (Wane and Chandler, 2002). Studies have also shown that women’s traditional knowledge has helped them manage their environment for generations (Glazebrook, 2011); however, their contributions are rarely recognized because activities like cleaning and weeding are considered part of their responsibilities on the domestic front. This study aims to highlight rural women’s contribution in environmental protection by examining how women in Makarfi Local Government Area (LGA) of Kaduna State, Nigeria, interact with their environment in different forms and how such interactions may contribute in protecting the environment. Sixty women shared their experiences and knowledge about the environment and how their traditional knowledge has helped them manage their interactions with the environment in a respectful and sustainable manner. This study did not only highlight the contributions of women in conserving the environment, but it also brought to the fore front challenges that women face in carrying out those activities. This is an important aspect of the discussion because most studies tend to focus on the former. The choice of the study site is significant because the Northern part of Nigeria has been described by the World Bank as underdeveloped compared to the rest of the country, many people turn to the environment for food and livelihood (World Bank, 2015). This study would add to literature in the field by highlighting a region that is underrepresented in studies. The study can also provide insights that can potentially contribute to policies on women’s land rights, access to forest resources and development of environmental preservation strategies.

Women as environmental custodians: A review

Women’s interaction with the environment has been studied from different perspectives at various times in history, however, since the 1970’s when the Ecofeminist movement highlighted the connection between the suppression and exploitation of women and the degradation and exploitation of the environment (Mies and Shiva, 1993), various groups, and regions have adopted the concept and applied it according to their realities. In Africa, where women are said to have a close connection to their environment because of their reliance on it, arguments have been made about the experience that these women may have gathered in the areas of environmental conservation by virtue of their constant and historical interaction with it. Studies have described this interaction in terms of women’s participation in subsistence farming, their Indigenous farming knowledge and methods that contribute to environmental conservation, and other studies also examine women’s engagement in their daily activities that constitute efforts towards conservation. In a study on Gender, Knowledge and Practice in the formation and use of African Dark Earth (AfDE), it was found that women in Liberia and Sierra Leon, through their daily activities such as cooking and cleaning, add organic matter such as ash, potash and left over food and stalk onto the soil to form African Dark Earth (Frausin et al., 2014). This soil enrichment method which is solely based on traditional knowledge is said to improve soil quality as evident in the better crop yield from that soil in comparison to other fields. Although it is argued that women’s reliance on the environment can sometimes be harmful to natural resources (Nankhuni and Findeis, 2004), this study shows that it can also be beneficial. However, there is need for more research and strategic planning to take into consideration factors such as poverty and cultural gender biases when mapping out conservation policies. The knowledge that most rural women in Africa rely on is largely based on traditions that have been passed down through many generations, it is therefore important to preserve such knowledge for future generations and women have an important role to play in this aspect. To emphasize the importance of traditional knowledge preservation, Debwa and Mearns (2012), highlighted the role of women, especially elderly women in preserving the knowledge of Indigenous vegetable production in Mantianeni, South- Africa. Young people in the community were showing little interest in the tradition and that raised concerns around sustainable production practices in the future. Elderly women in that community are looked up to as knowledge keepers, and therefore the responsibility of passing the knowledge lies on them. Through years of interaction with the environment, the older women have acquired knowledge that is crucial to maintaining the sustainable production of Indigenous vegetables in Mantianeni (Debwa and Mearns, 2012). Study has also shown that women’s efforts towards protecting their environment can manifest through traditional practices such as crop rotation, mixed cropping and selective planting. Glazbrook (2011) noted that women in Ghana use these techniques in food production and to help them cope with climate change effect without exerting more damage to their environment (Glazbrook, 2011). In Nigeria, women in rural communities play a major role in the agriculture sector. They engage in the production, processing and marketing of food crops and they are said to contribute between 60 and 90% of the total agricultural production task in their various communities (FAO, 2011). This makes them engage significantly with their environment. Studies have shown that contrary to popular opinion, rural women do not only take from the environment, but they also give back. In Plateau state, north central Nigeria, women contribute in environmental protection through activities such as environmental sanitation, tree planting and traditional farming methods like mulching to conserve soil moisture (Wuyep et al., 2014). In the south western part of the country, women in Pedro Village, Lagos state were found to be protective and conscious of their environment. They manifest this by engaging in waste management, drainage management, water resource management, flood management and subsistence agriculture; these are all efforts towards protecting their environment (Chukwu, 2014). As a coastal community, they often experience flooding and that could be further exacerbated by blocked drainages and improper waste disposal. The study by Chukwu (2014) shows that women play an active role in protecting their community and serve as enforcers of guidelines and penalties.

Most rural dwellers in Nigeria depend on firewood as their primary source of cooking energy (Federal Ministry of Environment- FME, 2006), largely due to the lack of affordable alternatives and since women (especially women in rural communities) are mostly responsibility for cooking and gathering firewood, they are seen as significant users of this resource (Blackden and Quentim, 2006). While the level of tree harvesting by rural dwellers in Nigeria is said to be significant- 80% (FME, 2006), it is important to highlight the various roles women play in giving back to the environment and not to lose sight on areas of growth. This is why this study highlights both challenges and potentials; this would potentially give a more holistic picture of the issue and provide information for a more comprehensive policy formulation.

Description of study community

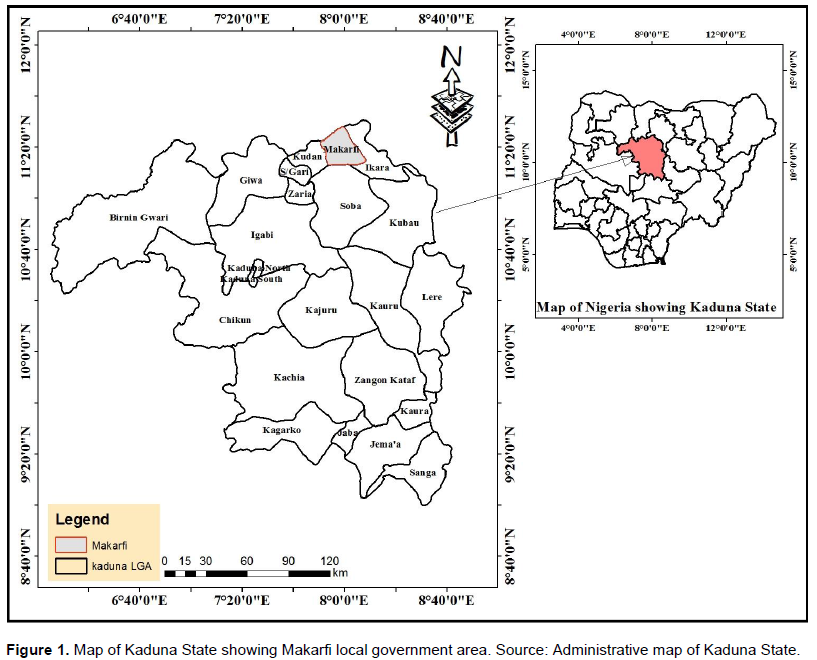

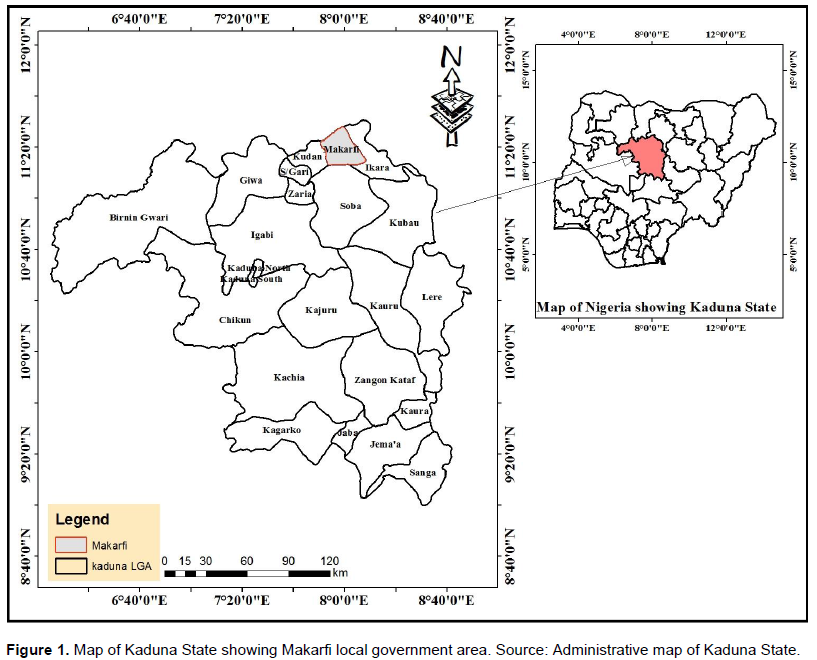

Makarfi LGA is located in the northern part of Kaduna states on latitude 11°21N and longitude 7°401 E. It is bounded by Rogo LGA of Kano State at the northwest, Ikara LGA to the east, Kudan LGA in southwest and Sabon Gari LGA in the Southeast, it consist of ten wards with an aerial coverage of 650 km2 (Umar et al, 2009) (Figure 1). It is located on a gentle undulating plain which extends almost unbroken from Sokoto down to Tuguddi near Agades in Niger Republic. Data shows that between 2006 and 2011, Makarfi’s population was expected to grow from 146,574 to 170, 574 (National Population Commission of Nigeria, 2010). The growing population has led to increased demand for farm lands; the many years of interference with its natural environment has led to a derived vegetation cover at present. Presently, its vegetation cover consist of Isoberlina, Dorka’ isoberlina, tmentosa, and Uapca Fogemis with a well-developed grass layer of Tufted Andropenea.

The study area is characterized by wet and dry seasons. The dry season begins in November and ends at May, and then the wet season begins with the little showers of rain leading up to its peak in August. It’s marked with high temperature with major maximum of 40°C in April but a low atmospheric humidity (15 to 65%). The soil in the area consist of “fadama soils” comprising of vertisal’s and clay (hydro-morphic), which promotes dry season farming of crops such as rice, sugar cane, and vegetables of various kinds. The upland soils promote the cultivation of crops like guinea corn, millets, soya beans, beans and groundnut (Kaduna State Government Development Strategies on Fadama II, 2002). Due to the favorable environmental conditions that support the growth of many crop varieties, farming has for many years been a major source of livelihood in the community (Strahler and Strahler, 2005).

This paper is based on a study conducted in Makarfi LGA October-November, 2016. In order to get a fair representation, six women were randomly selected from each of the following ten wards in Makarfi: Dandamisa, Danguzuri, Gazara, Gimi, Gubuchi, Gwanki, Makarfi, Mayare, Nasarawa Doya and Tudun Wada, respectively. A total of sixty women, between the ages of twenty to sixty years participated in the study. A semi-structured interview was conducted for each of the participants. These women shared their experiences from various perspectives, based on the roles and responsibilities they take up in their households and community. Since the study was aimed at highlighting women’s role in environmental conservation, this age group (20-60) was ideal because women within this group in the community are mostly responsible for activities such as domestic work, farming and harvesting (Ekpo, 2012). This selection also provides an opportunity for generational knowledge perspective.

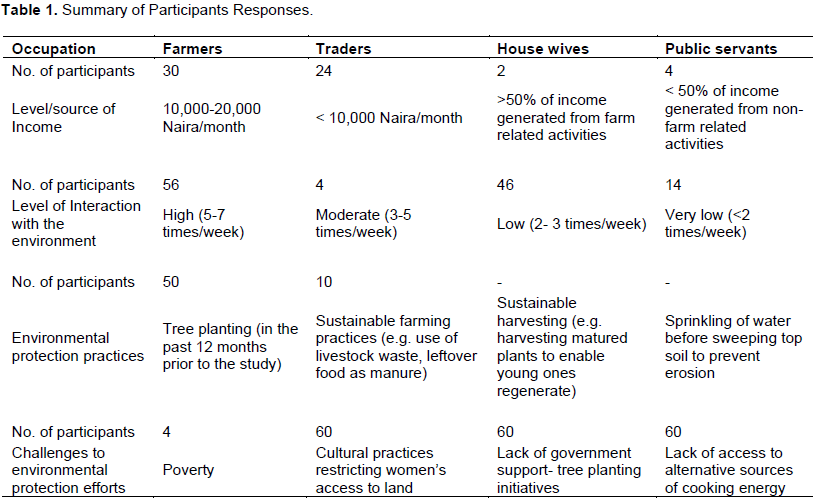

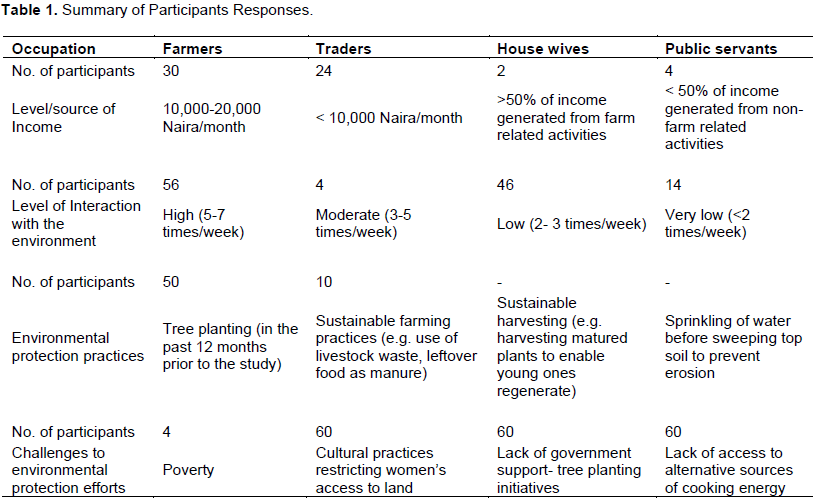

Based on data collected, thirty women (50%) reported their occupation as farmers, while twenty four (40%) regard themselves as traders. The remaining six women reported occupations such as housewife (3%), and public servant (7%) respectively. As to the question of whether their various occupations make them interact with their environment, majority of the women (83%) agreed that as a result of their activities as farmers, traders or housewives, they are in constant contact with their environment. Women who engage significantly in farming activities in the community participate in various stages of farming. Women are involved in farm clearing, they engage in planting and weeding and they also participate actively in the harvesting and the sale of food. The seven percent of participants that reported as being public servants also said they engage in some kind of gardening, therefore they get some of their food from their gardens and through purchase as well. This goes to show that regardless of the occupation, all of the participants engage with the environment at various levels and degrees.

As part of their farming activities, women in Makarfi apply organic matter such as livestock waste, leftover food and ash to help enhance crop growth. These procedures are said to also help enhance soil nutrients (Chukwu, 2014). Some women also engage in tree planting, although this activity is practised to a lower degree compared to the former (sustainable farming practises) as only seven percent of women admitted to planting at least a tree in the past year. Another form of environmental protection activity that women from the study area engage in involves sprinkling water on the soil before sweeping. This, the women say protects top soil, which in turn helps cub surface erosion. Thirteen percent (13%) of participants said they engage in sustainable harvesting so that those plants would be available for next time. One participant said:

“I remember been taught by my mother to carefully harvest spinach leaves to allow new leaves to grow back”

(participant 50. Field interview, October, 2016).

Fire wood is the primary source of energy in the community and participants of this study admitted to utilizing fire wood as the first energy source for cooking. This is largely due to its accessibility and affordability. This is significant because ninety four percent (94%) of the participants fall under the income bracket of ten to twenty thousand naira ($32-$63) per month, so affording an alternate source of energy would come as a challenge to most of them (Chukwu, 2014). Some women also engage in tree an alternate source of energy would come as a challenge to most of them. However, they also admitted to cutting tree branches in ways that would allow for future germination of such tree. Furthermore forty six women (77%) said they gain up to eighty percent (80%) of their income through activities such as farming, sale of farm produce, sale of firewood and wild food. These activities happen in close relation with the environment, which speaks to why they would be concerned with the health of their environment.

In their quest to protect their environment, these women reported facing challenges of various kinds. Of the sixty women that participated in the study, forty five percent (45%) of them said they are enthusiastic about protecting the environment; however they are limited by their state of economic well being. These women recognize that activities such as tree felling and excessive use of farmlands for crop production sometimes bring negative effects to the environment, but they lack the resources to move to other sources of energy in order to reduce dependence on trees for firewood. Some twenty five percent (25%) of the women reported having challenges with cultural practises that restrict women’s access to land. Because of limited resources women are often not able to purchase land or access credit to acquire land. Cultural practises that discriminate against women inheriting landed properties also pose a barrier to land acquisition. This challenge cuts across many rural communities in Nigeria where women’s access to land is largely done through male relation (Simpa, 2014). Because of limited access, these women cannot easily move from one farmland to another, to limit overuse of certain spaces. Even with the best of intentions for the environment, a woman would want to look after her family by making sure she farms on available land. This is why twenty percent of the women say that the government has a role to play in the conversation. The women said that the government can assist by providing affordable energy sources, more tree planting initiatives to make up for trees lost resulting from human activities. Table 1 summarizes the results.

This study has shown how women, through their various occupations as farmers, housewives, traders and public servants have close relations with the environment and relies on it for food and income. Because of how significant the environment is to their livelihood, women in Makarfi carry out various practices to help protect the environment. This include sustainable farming practices (like the use of organic matters such as livestock waste and left over food to enhance crop production), tree planting, sustainable harvesting (harvesting matured plants to enable young plants to regenerate) and practices to reduce soil erosion (like sprinkling of water on the ground before sweeping). This study has also highlighted challenges that women face in their quest to protect the environment; they range from poverty, to challenges with cultural practises and the lack of government assistance. Since women in rural Nigeria contribute significantly to agricultural labour (IFAD, 2012), and are mostly responsible for managing their household chores (like sourcing for cooking fuel, cleaning their surrounding, and waste management), it is only logical that policies reflect the important position of these women. However, rural women and women headed households in the county’s rural communities remain among the poorest in their communities (Oluwatayo, 2014). Until there is a sincere commitment by policy makers to empower rural women and recognize them for the important role they play, a healthy natural environment with reduced threat to resources such as trees may be extremely difficult to achieve in Nigeria without the commitment and input from a group (rural women) who have close interaction with the environment. Many participants of this study discussed their willingness and desire to do more to make sure the environment that provides for their needs today will still be there for their children in the future. With support, these desires can be fulfilled. The environmental protection practices already used by women in Makarfi are based on traditional knowledge, however they can make use of more training on other innovative techniques that would complement their traditional knowledge to help them better protect their environment. Due to their frequent interaction with the environment, these women can potentially form part of natural disaster management programmes and climate change adaptation programmes. Customary laws should better protect women’s rights and access to resources such as land. This would help women get more access to incentives such as loans, which will in turn help empower them to choose more environmental friendly options like using an alternative source of energy instead of cutting down trees, or using more organic options during crop production. The importance of women’s participation in environmental protection has been reiterated by the United Nation (UN, 2002). When rural women are seen as partners in policy decision forums, then their contributions and traditional knowledge will begin to be recognized and appreciated. Their contributions can serve as foundations that can potentially be built upon towards sustainable rural development.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Blackden MC, Quentim W (2006) Gender, Time Use and Poverty in Sub Saharan Africa. World Bank Working paper No. 73.

|

|

|

|

Chukwu MN (2014). A Study on Gender Involvement in Environmental Protection in Pedro Village, Lagos. Acad. J. Interdiscip. Stud. 3(7):20-24.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Debwa TP, Mearns MA (2012). Conserving Indigenous Knowledge as the key to the Current and Future use of Traditional Vegetables. Int. J. Inform. Manag. 3(6):564-571.

|

|

|

|

|

Ekpo R (2011). Comparative analysis of the influence of socio-economic variables on women's attitude to family planning in Jaba and Makarfi Local Government Areas of Kaduna State. Unpublished Master Degree Thesis, Department of Geography, Faculty of Sciences, Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria.

|

|

|

|

|

Federal Ministry of Environment (2006). Approved Nigeria's National Forest Policy

|

|

|

|

|

FAO (2011). The State of Food and Agriculture (2010-2011): Women in Agriculture, Closing the Gender Gap for Development. Rome.

|

|

|

|

|

Frausin V, Fraser JA, Narmah W, Lahai MK, Winnebah TR, Fairhead J, Leach M (2014). God made the Soil, but we made it Fertile": Gender, Knowledge, and Practice in the Formation and use of African Dark Earth in Liberia and Sierra Leone. Hum. Ecol. 42(5):695-710.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Glazebrook T (2011). Women and Climate Change: A case Study from North Eastern Ghana. Hypathia, 26(4):762-782.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

International Fund for Agricultural Development – IFAD (2012). Rural Poverty in Nigeria: Agriculture in the Federal Republic of Nigeria

|

|

|

|

|

Mies M, Shiva V (1993). Ecofeminism. Halifax N.S. Fernwood publications. 24.

|

|

|

|

|

Nankhuni FJ, Findeis JL (2004) Natural Resources-Collection Work and Children's Schooling in Malawi. Agricultural Economics, Blackwell 31(2-3):123-134.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

National Population Commission (NPC) (2009). 2006 population census: Final Figures. NPC, Abuja.

|

|

|

|

|

Oluwatayo IB (2014). Gender Dimensions of Poverty and Coping Options among Small Holder Farmers in Eastern Nigeria. Mediterr. J. Soc. Sci. 5(27):49-61.

|

|

|

|

|

Simpa JO (2014) Poverty Determinants Among Female Headed Household Rural Farmers in Nassarawa State, Nigeria. PAT 10(1):93-109.

|

|

|

|

|

Strahler A, Strahler A (2005). Physical geography. Science and systems of the human environment. 3rd Edition. John Wiley and Sons, Inc. United State of America.

|

|

|

|

|

United Nations (2002). Importance of Women's Participation in Protecting Environment Stressed. UN press release, March 6, 2002. WOM/1325

|

|

|

|

|

Umar A, Kabiru F, Zakari A, John AA, Emmanuel A, Felicity MF, Mikail AK, Peter AS, Hebert M (2009). Regional development plan of Makarfi Local Government Area. Unpublished undergraduate paper presentation. Department of Urban and Regional Planning. Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Kaduna State, Nigeria.

|

|

|

|

|

Wane N, Chandler DJ (2002). Cultural knowledge and environmental education. A focus on Kenya's indigenous women. Can. J. Environ. Educ. 7:86-98.

|

|

|

|

|

Wuyep SZ, Dung VC, Buhari AH, Madaki DH, Bitrus BA (2014). Women Participation in Environmental Protection and Management: Lessons from Plateau State, Nigeria. Am. J. Environ. Protect. 2(2):32-36.

Crossref

|

|