ABSTRACT

Wetlands are one of the world’s most important environmental assets but currently face complex challenges. Wetlands’ long-term sustainability require participation of the riparian communities in their management, yet this involvement in seeking solutions to wetland’s resources use remains a grave challenge. Yala Wetland, Kenya is a very important resource whose challenges revolve around land and water resource use for competing interests and from catchment degradation. Consequently, action research was conducted to assess level of and effectiveness of Yala Wetland Community Participation in Yala Strategic Environmental Assessment and Land Use Planning processes through Yala Project Advisory Committee Framework. The study targeted 410 local communities, thirty-four key informants, and 187 students from learning institutions. The study revealed that utilization of Yala resources has been partly informed by how the wetland communities perceive its formation. Further, they identified key environmental issues, their root causes and corresponding opportunities that Yala Land Use Plan needed to address. The analysis also showed existing gaps in integration of community information and scientific information, disconnect between decision making and requisite scientific and practical evidence; and absence of community sensitive governance structure. The study integrated local communities’ vast knowledge and planning information and formed Yala Swamp Management Committee with communities at the centre of conservation. Additionally, there is a secretariat led by a Community Facilitator to coordinate execution of the Conservation Area Management Plan 2019-2029. The final Yala Land Use Plan developed in participatory manner itemized three main land uses namely Conservation areas, Agricultural areas and settlement areas.

Keywords: Yala Wetland, Community Participation, Land Use Planning, Governance.

Wetlands occur where the ground water table is at or near the land surface, or where the land is covered by water (Ramsar Convention Secretariat, 2016), and are one of the world’s most important environmental assets which provide homes for large, diverse biota as well as significant economic, social and cultural benefits related to timber, fisheries, hunting, recreational and tourist activities. They constitute an important resource for riparian communities and therefore it is important that communities participate in their management. Community participation in natural resource management has evolved from the realization that people living with natural resources should be responsible for their management and benefit from using the resources (Ostrom, 1990; WWF, 2006; Lockie and Sonnenfeld, 2008; GoK, 2010a). This is central to sustainable natural resource management at all levels. The Aarhus Convention of 1998 states that citizens must not only have access to information but must also be entitled to participate in decision making and have access to justice in environmental matters (DETR, 2000; Stec et al., 2000). However, participation of local communities in seeking solutions to wetlands resources use remains a grave challenge as managers of participation processes engage in low level consultations that do not empower them to co-manage these resources alongside government agencies mandated to do so (GoK, 2010a; Springate-Baginski et al., 2009).

A synthesis of research and policy priorities for papyrus wetlands presented in Wetlands Conference in 2012 concluded that more research on the governance, institutional and socio-economic aspects of papyrus wetlands is needed to assist African governments in dealing with the challenges of conserving wetlands in the face of growing food security needs and climate change (van Dam et al., 2014). The other three priorities were the need for: better estimates of the area covered by papyrus wetlands as limited evidence suggest that the loss of papyrus wetlands is rapid in some areas; for a better understanding and modelling of the regulating services of papyrus wetlands to support trade-off analysis and improve economic valuation; and research on papyrus wetlands should include assessment of all ecosystem services so that trade-offs can be determined as the basis for sustainable management strategies (‘wise use’).

In Africa, wetlands degradation is on the increase as wetland ecosystems are relied upon to lessen industrial, urban and agricultural pollution and supply numerous services and resources (Nasongo et al., 2015; Kansiime et al., 2007). Similarly, lack of recognition of the traditional values of these wetlands, desire for modernisation and failure to appreciate their ecological role aggravate their degradation (Maclean et al., 2003; Panayotou, 1994).

Public participation has been the focus of many Environmental Impact Assessments (EIAs) and Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) studies globally (Doelle and Sinclair, 2005; Hartley and Wood, 2005). This article defines public participation as the process of ensuring that those who have an interest or stake in a decision are involved in making that decision. Participation has become a key element in the discussion concerning development particularly in natural resources management (Cooke and Kothari, 2001). Today, the concept is seen as a magic bullet by development agencies who are making participation one, if not the core element of development (Michener, 1998).

According to the International Association of Public Participation (IAP2, 2008), public participation consists of five levels: information (lowest level, where participation does not go beyond information provision), consultation, involvement, collaboration and empowerment (highest level, where the public are given a final say on the project decision).

Okello et al. (2009) study on public participation in SEA in Kenya concludes that it is unsatisfactory. The study noted that Environmental Management and Coordination Act (EMCA) of 1999 and its 2015 amendment and Environmental Impact Assessment Audit Regulations 2003 (EIA AR) did not have provisions detailing consultation with the public during SEA and that knowledge and awareness of the public at all levels of society were found to be poor (GoK, 2015). The undoings of public participation include information inaccessibility in terms of readability and physical access, inadequate awareness of the public on their roles and rights during EIA, incomprehensible language and incomplete regulation for public participation during SEA. These undoings have to be overcome if public participation in Kenya has to be improved and move to higher levels (that is, collaboration-empowerment) of participation on the spectrum of public participation level.

Community participation in Yala Wetland SEA and LUP

Yala Wetland is an important resource shared by Siaya and Busia counties of Kenya. It supports the livelihoods of surrounding communities, including water, papyrus and fisheries, among others, and provides vital ecosystem services such as purification and storage of water. It also acts as a carbon sink, thus regulating global and local climatic conditions and is internationally recognized as a Key Biodiversity Area that hosts globally and nationally threatened bird, fish and mammal species. The Wetland is also an important agricultural asset that has attracted both local farmers and external agricultural interests (EANHS, 2018).

This important resource is facing many challenges that revolve around land and water resource use for competing interests and also from catchment degradation (GoK, 2018, 1987; Odhengo et al., 2018a; Ondere, 2016; Odero, 2015a; Odero, 2015b; Muoria et al., 2015; van Heukelom, 2013; Raburu, 2012; Thenya and Ngecu, 2017; Onywere et al., 2011; GoK, 2010b; Kenya Wetland Forum, 2006; Lihanda et al., 2003; Otieno et al., 2001; GoK, 1987). These challenges pointed to the need for a well-considered Land Use Plan (LUP) that would provide a rational and scientific basis for future development and use of the resource. This situation prompted and encouraged County Governments of Siaya and Busia, and Nature Kenya to initiate processes that culminated in the present effort to prepare a LUP that will help resolve these challenges so that Yala Wetland will be able to sustainably support local residents’ livelihoods while its ecological integrity and that of its associated ecosystems is protected.

Preliminary processes implemented by Inter-ministerial Technical Committee (IMTC) and a Deltas Management Secretariat prepared a LUP Framework to guide the planning process and was agreed upon by stakeholders. The IMTC’s responsibility is coordination, policy and planning processes of major deltas in Kenya. The Framework was as result of a participatory and collaborative process that involved various stakeholders at the local, county and national levels. As required by Kenya Constitution article 69(1) and part VIII section 87-92; and section 115 of County Government Act, 2012 on devolution provisions and part 2 section 6 (1-2) Public Participation Bill, 2020 provided for participation of local communities in the Land Use Planning process through a Yala Project Advisory Committee (YPAC) (GoK, 2010, 2012a; GoK, 2012b; GoK, 2020). The LUP process also benefited from a SEA process that served to assess the environmental implications of the Land Use Plan. The action research reported in this paper sought to: (1) assess the historical and current state of community participation in SEA/LUP of Yala Wetland ecosystem management; (2) identify the local communities’ key environmental issues for SEA/LUP of Yala Wetland ecosystem management; (3) incorporate the results in the Yala Wetland SEA/LUP processes.

The Yala wetland area

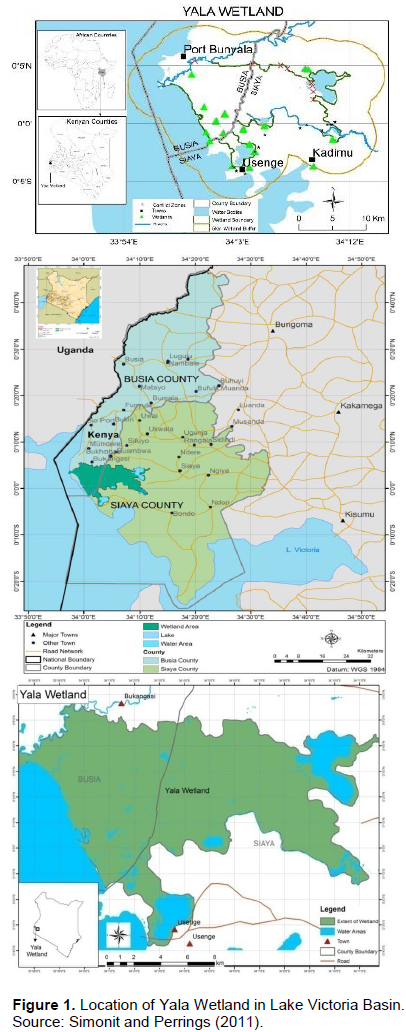

Yala Wetland is located on the north eastern shoreline of Lake Victoria between 33° 50’ E to 34° 25’E longitudes to 0° 7’S to 0° 10’N latitude (Figure 1), and is situated on the deltaic sediments of the confluence of both Nzoia and Yala Rivers where they enter the north-eastern corner of Lake Victoria. It is highly valued by local communities (NEMA, 2016). Yala Wetland is Kenya’s third largest wetland after Lorian Swamp and Tana Delta and has a very delicate ecosystem. It is shared between Siaya and Busia counties of Kenya and covers an area of about 20,756 ha (about 207 km2) (JICA, 1987; LBDA, 1989; Odhengo et al., 2018b).

Yala Wetland and its environment have a high population density (KNBS, 2010). The Siaya County side had human population density estimated at 393 km-² in 2009 while Busia County had a higher concentration of up to 527 persons/km² (KNBS, 2010).

Based on the 2019 National Census Results, the population of Siaya and Busia Counties were 743,946 with a growth rate of 1.7 % and 833,760 with a growth rate of 3.1%, respectively. The population of the planning area (wetland and its buffer of 5 km radius) was estimated at 130,838 in 2014 and was projected to be 171,736 in 2030 and 241,280 in 2050 (KNBS, 2010). The mean household size was 5.05, although population density in the wetland and adjacent areas were not uniform. High population concentrations were found in the Busia County side around the banks of Nzoia River and to the South in Siaya County side around Usenge town and north of Lake Kanyaboli (KNBS, 2010).

Biodiversity

The Yala Wetland, which is the largest papyrus swamp in the Kenyan portion of Lake Victoria, is an exceptionally rich and diverse ecosystem, containing many rare, vulnerable and endangered species of plants and animals (EANHS, 2018). The wetland is almost entirely covered in stands of papyrus.

Over 30 mammal species have been recorded in the wetland. They include the Sitatunga (Tragecephalus spekeii), a shy and rare semi-aquatic antelope that is nationally listed as Endangered (Thomas et al., 2016; Wildlife Act, 2013; KWS, 2010; IUCN, 2016). The wetland provides an important refuge for Lake Victoria cichlid fish, many of which have been exterminated in the main lake by the introduction of the non-native predatory fish, Nile Perch (Lates niloticus). Recent surveys in Lake Kanyaboli recorded 19 fish species within nine families, which included all the two critically endangered cichlids species: Oreochromis esculentus and Oreochromis variabilis (IUCN, 2018; KWS, 2010; Ogutu, 1987a, b). The fishes use the swamp as a breeding ground, nursery, and feeding grounds (Aloo, 2003).

The Yala Wetland climate has a variable rainfall pattern that generally increases from the lake shore to the hinterland (Ekirapa and Kinyanjui, 1987; Awange et al., 2008). The mean annual rainfall ranges from 1050 to 1160 mm and is bimodal. The mean annual daily maximum and minimum temperatures are 28.9 and 15.9°C, respectively giving a mean annual temperature of 24.4°C (Luedeling, 2011; Semenov, 2008).

The hydrological conditions within the Yala Wetland is characterized by five main water sources, namely: inflows from the Yala River, seepage from River Nzoia, flooding from both rivers, backflow from Lake Victoria, local rainfall and lakes within Yala Wetland (Okungu and Sangale, 2003). River Yala is the main source of water for the swamp and other satellite lakes. The naturalized mean monthly discharge is 41.1 m3/s. The lowest flows barely fall under 5 m3/s in the months of January to March while the highest discharge of 300 m3/s occur in the months of April/May and August/ September. The minimum suspended silt load of River Yala Water is 543 ppm (BirdLife International, 2018; Sangale et al., 2012; Okungu and Sangale, 2003).

Originally, the Yala River flowed through the eastern swamp (now ‘reclaimed’) into Lake Kanyaboli, then into the main swamp, and finally into Lake Victoria via a small gulf. The Yala flow is now diverted directly into the main swamp, and a silt-clay dike cuts off Lake Kanyaboli, which receives its water from the surrounding catchment and through back-seepage from the swamp. A culvert across the mouth of the Yala, some metres above the level of Lake Victoria, has cut off the gulf on the lake and, through back-flooding, created Lake Sare (BirdLife International, 2018, Gichuki et al., 2005). This river flows on a very shallow gradient through small wetlands and saturated ground over its last 30 km before entering Lake Victoria through its own delta. The soils in this region have a very high clay content which impedes ground water flow but there is known to be a gradual movement of seepage water into the northern fringes of the Swamp. Flooding occurs annually and the very high discharge rates mean that the river channels are overtopped with floodwater passing into Yala Swamp. Parts of the western swamp lie below the level of Lake Victoria and are constantly filled with backflow in addition to being subjected to flooding from the lake and upper catchment.

Annual rainfall in Lake Victoria Basin (LVB) encompasses a bimodal pattern. The Yala/Nzoia catchment has high precipitation in the Northern highland (1,800-2,000 mm per annum) and low in the South-Western lowlands (800-1,600 mm per annum). Local rainfall contributes to Yala Wetland water. The water balance for Yala Wetland also includes the water retained within the three freshwater lakes found within the swamp: Kanyaboli (10.5 km2), Sare (5 km2) and Namboyo (1 km2). Lake Kanyaboli has a catchment area of 175 km2 and a mean depth of 3 m. Lake Sare is an average of 5 m deep and Lake Namboyo has a depth of between 10 and 15 m (NEMA, 2016; Owiyo et al., 2014a; Dominion Farms, 2003; Envertek Africa Consult Limited, 2015).

This study employed action research methodologies as the appropriate tool that would seek to assist the “actor” in improving and/or refining his or her actions. Action research also seeks transformative change through the simultaneous process of taking action and doing research, which are linked together by critical reflection. Kurt Lewin, then a professor at MIT, first coined the term "action research" in 1944 (Mills, 2000).

Sampling and data collection

The study used non-random purposive and stratified sampling to collect data. A total of 410 respondents from 60 local community groups participated in focus group discussions (FGDs) from the swamp and adjacent buffer zone including: beach management units, women groups, youth groups, smallholder farmer’s cooperatives, religious leaders’ associations, sand harvesters, and YPAC members. There were 34 key informants interviewed mainly elders and change makers on historical, cultural and indigenous knowledge information. Data was also collected from 187 students who participated through essay writing, debates and artworks. These were drawn from primary (12), secondary (5) and post-secondary polytechnics and colleges (2) in Yala Wetland and its buffer zone. The target organizations and individuals were active in wetland conservation and spatially spread all over Yala Wetland and its buffer zones. Additionally, the researcher kept a journal where he recorded descriptive accounts of his research activities, experiences and critical reflections. Sample size determination for this research was based on judgment with respect to the quality of information desired and the respondents’ availability that fit the selection criteria of involvement in conservation activities in the swamp (Sandelowski, 1995). According to Neuman (1997), it is acceptable to use judgment in non-random purposive sampling and reiterates that there is no ‘magic number’.

Data analysis

Qualitative data were analyzed in using content analysis methods. Content analysis technique allowed the researcher to categorize and code the collected information based on participants’ responses to each question or major themes that emerged from FGDs, in-depth interviews, essays, debates and artworks. Content analysis as Babbie (2015) argues is useful since it captures well the content of communications generated through interviews, essays and FGDs in an inductive manner, where themes were generated based on emerging similarities of expression in the data material. Many of these elements provided quotations in the write- up of research findings and other similar elements were quantified using descriptive statistics to give a sense of the emerging themes and their relative importance according to the respondents.

Respondents also conducted priority ranking of issues to arrive at overall prioritisation of issues that informed LUP content.

The study dealt more with people’s perception than with statistically quantifiable outputs. Thus, data analysis to gauge these perceptions was done by calculating percentage response (Neuman, 1997). The response rates were calculated using the following formula.

Response (%) = x / y × 100

where x: respondents who gave feedback and y total number of respondent groups. To grade the percentage response, a modification of Lee’s (2000) EIA study review package was used (Table 1).

The researcher used satellite images from Google Earth which provided detailed photographic evidence of the condition of the wetland and various land use changes in Yala Swamp over years. They were also used to determine the current size of the wetland in line with revised definition of the wetland and various land cover/use changes in the swamp over the years. Satellite images and GIS analysis has been used variously to determine land cover/land use changes (EMCA, 2012; Turner, 1998; Liverman et al., 1998; Chambers, 2006; Ampofo et al., 2015; Lillesand and Kiefer, 1987).

Literature review was conducted on public participation, policies, laws and relevant studies that provided secondary data and a valuable source of additional information for triangulation of data generated by other means during the research and this has also been used by many researchers (Friis-Hansen and Duveskog, 2012; IYSLP, 2017).

Overall, a multidisciplinary research using case study design employed exploratory action research with both qualitative and quantitative methods of data collection and analysis. Appreciative Inquiry (AI) methodology and participatory approaches and secondary data were used in data collection and analysis (Dweck, 2008; Cooperrider et al., 2008). The secondary data include policy and legal frameworks, wetland ecosystem management guidelines and procedures, relevant studies to Yala Wetland and other sensitive ecosystems elsewhere. This qualitative research used was supported by quantitative methods on how contextual factors and processes affected the planning and management of Yala Wetland ecosystem. Strauss and Corbin (1990) noted that quantitative and qualitative methods are tools that complement each other, while Greene (1995) in her doctoral research used and shows the value of journaling as research methodology for in-depth reflection by the researcher and vital in action research designs. Greene (1995) says “learning to write is a matter of learning to shatter the silences, of making meaning, of learning to learn” (p.108).

Community participation in Yala Wetland ecosystem results are presented under formation of the wetland and its value to local communities, and essential indigenous knowledge systems used by communities in managing Yala Wetland ecosystem.

Formation of Yala Wetlands, its value and community involvement in its management

According to the recollection of the local communities, the swamp was a flat ground inhabited by the local people prior to the 1960s, when heavy rains caused its formation. First, before 1960s, the swamp was a water body which later disappeared allowing the local populations to move in for cultivation. They reported that Sare was a small water pool where children played football, and that in their experience, there have been three cycles of water drying or significantly reducing, namely cycle one 1917-1920s; cycle two 1960s-1970s; and cycle three 1980s onwards. Further, they also reported that they had heard from their forefathers that Lake Victoria had also dried completely twice in its history of existence. This has been corroborated by studies on Lake Victoria (Awange and Obiero-Ong’anga, 2001). Second, the swamp partly formed from flooding experienced in 1960 - 1963, which they believed to be a curse from gods. They recalled that in December 1962 and much of 1963 there were heavy rains (kodh uhuru meaning the rain at independence) which is equivalent to today’s El Nino rains, and that the flooding continued into the 1970s, causing malaria and other challenges that forced most people to move to high grounds. Initially, there was a small opening by the lakeside at Goye in Usenge, but with 1960s rains, it widened, A ferry was brought but with increased rains, it was swept to Mageta islands. They then used boats until the two areas were linked by a causeway. The families in Yimbo dispersed over time and some of them moved to other places in Bunyala, Alego, Gem and other far off places. They still retain the names from Yimbo like Nyamonye, Usenge, and Uriri in Alego.

In their perspective, “Lake Kanyaboli is a mystery (en hono), when the water dried from Sigulu an elder, Wanjiri Kosiemo, discovered the dried land for the people of West Alego and people moved in to farm. There were a lot of indigenous fish species like Kamongo (mudfish) and a lot of food such that there were no thefts from the farms.” An elder remembers this and states that Ikwaloga mana ka onge, meaning people steal food only when there is lack of it. In 1968, a road was constructed through Yala Swamp, with the Lolwe bus company route passing through the swamp. The communities further explained that Lake Sare is a result of backflow of River Yala from Lake Victoria, and they attributed the expansion of the swamp to the forced diversion of River Yala’s course as the waters spread into the swamp without going direct into both the Lakes Kanyaboli and

Victoria as was before. The inhabitants of Mageta were driven away by tsetse fly infestation in 1929 but returned after successful government Tsetse eradication project in the islands in mid-sixties. They noted that the local communities created beliefs out of some experiences and some believed going back to Mageta was not going to be fraught with bad omen. A third community explanation on the formation of wetland was linked to the construction of Owen Falls Dam in Uganda in 1954 which they believed resulted into the beginning of backflow of water.

The Bunyala community provided an additional explanation, linking flooding to River Nzoia channel expansion for construction of Webuye Paper factory. In Musoma where River Nzoia enters Lake Victoria, there is a backflow that is partly responsible for submerging villages in the swamp. There are 10 Yala Swamp islands inhabited by 36 clans spread across 39 villages. Among the indigenous communities living in those 10 swamp islands include: Bulwani, Maduwa, Bukhuma, Siagiri, Iyanga, Khumabwa, Maanga, Bungeni, Runyu, Rukaza, Kholokhongo, Nababusu, Gendero, Mauko, Bubamba, Buongo, Siagwede, Siunga, Bunofu, Busucha, Mugasa, Isumba, Ebukani, Bumudondu, Erugufu, Ebuyundi, and Khamabwa.

Therefore, it can be stated that the utilization of Yala Wetland resources has been partly informed by how the local communities perceive its formation. For those who perceived it as God’s gift for them, they utilize swamp resources as their own and as such take genuine care of the resources therein. For example, they see Lake Kanyaboli and the Yala Swamp as rare fish gene bank. Additionally, it has religious and cultural values for them. The Yala Swamp is a historical site that comprises of important components of the Luo and Luhyia cultural heritage (Got Ramogi) where the Luos first settled in Kenya having come from Uganda before dispersing to other parts of Kenya; Gunda Adimo (historical sites). For the Bunyala communities including 36 villages in the swamp, the wetland is their home from where they derive their entire livelihoods. Besides, their ancestors and recent family members who died have been buried there, bestowing special recognition of the spirits of their family members whom they insist they have obligation to care for. Other community wetland formation postulations do not support sustainable utilization of the swamp resources because they consider it a menace which causes floods and government resources who decides how to use without regard to the local communities; thus requires mindset change if they have to change to support sustainable interventions for the wetland. Therefore, improvements to sustainably manage the wetland ecosystem ought to factor the historical and contextual information and mindset change among wetland communities towards the wetland In final SEA and LUP reports, this historical and contextual information was included as chapter 4 in the SEA report, titled understanding the Yala Swamp, recent history of the Yala Swamp that shaped final LUP plan and its implementation plan and other related ecosystem management plans like the Yala Swamp Indigenous Conservation Area Management (ICCA) for 2019-2029.

The essential indigenous knowledge systems used by communities in managing Yala Wetland ecosystem

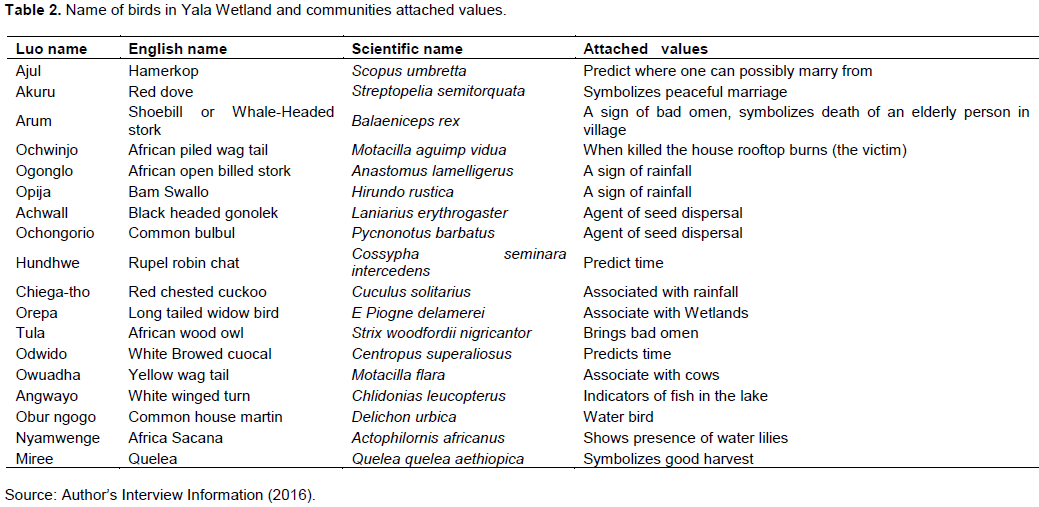

The local communities have been managing the wetland ecosystem using various indigenous knowledge systems that promote wise utilization and concern for the other users like the government, wildlife and marine animals. However, not every community member ascribes to these ideals hence conflicts over the wetland resources also occur. For example, the communities have developed positive conservation practices by attaching defined significance to the various wildlife species: some birds are totems therefore cannot be eaten by those communities. Table 2 shows various birds and their associative conservation values as seen by wetland communities as documented from some elders who are custodians of wetland information. This valuable indigenous ecological information has been shared during wetlands and environment days to raise the consciousness the rest of wetland communities to uphold positive attitude towards those birds and conserve them for their utility to the communities.

During the study, two relatively older members of the community (one 89 and one 78 years old) could narrate these historical events but very few young ones (like one 27 years) could. However, there was no documentation of these historical information of how the wetland communities used to manage the wetland. Therefore, there is urgent need to document and preserve this information and disseminate it to fill in the integration need for planning and management purposes of the wetland ecosystem and other land uses in the area.

The indigenous knowledge systems about Yala Wetland are vital for planning and management and hence the urgent need for their preservation. The local communities have managed the swamp using various indigenous knowledge systems that promote wise utilization, concern for the other users like the government, wildlife and wetland animals. However, not every community member ascribes to these ideals hence conflicts over the wetland resources. For example, the traditional totems and taboos system which are positive conservation practices arising from attaching some significance to the various animals and birds and thereby regulating their exploitation is close to the culling practice of sustainable harvesting of wildlife resources practiced in formal wildlife management. Further, the analysis showed the need for integrating local communities’ knowledge and scientific knowledge in the planning and management of the ecosystem.

These indigenous knowledge systems have since been recognized and used in the implementation of LUP and other ecosystem management plans. The key environmental events such as Wetland days, Environmental days are currently being used to disseminate LUP plans have been allocating sessions where elders share this knowledge and in schools, environmental awareness and education sessions in the region are also incorporating these.

Key environmental issues SEA/LUP of Yala Wetland ecosystem planning and management identified by local communities

The Yala Wetland communities identified key environmental issues that should inform SEA and LUP development processes of the wetland management. The main environmental challenges identified in order of priority (from highest to lowest) are: encroachment and reclamation of the wetland by the locals for development projects; burning of papyrus (resulting in the loss of biodiversity, fish breeding grounds, bird habitats and livelihoods); high human population density; resource use and related conflicts (human and wildlife conflicts); conflicts among the local communities on boundary issues and perception of unequitable benefit sharing from Dominion Farm (Alego and Yimbo communities); conflicts between the local community, the investors, government and third parties (Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), Community Based Organisations (CBOs), Media); disappointment and apathy due to unfulfilled promises by Dominion Farms (subsidized price of rice; broken promises to pastors fellowship forum); declining water levels in Lake Kanyaboli; flooding and its negative effects; weak framework for local communities participation; incoherent implementation of wetland policies; Nile Treaty constraints on Lake Victoria catchments and River Nile utilization; low agricultural productivity and resultant food insecurity; threats to wetland wildlife species as large chunks of land have been taken by for agriculture; birds poisoning using chemicals around Bunyala irrigation scheme; and pollutants channeled into the wetland; poverty and associated inequalities; and alien invasive species. All these concerns were taken into account in completing SEA and LUP.

Causes of Yala Wetland environmental challenges

The respondents identified some of the root causes of the aforementioned environmental challenges as increasing population and destruction of biodiversity; underground streams flowing back into the wetland causing flooding; high cases of malaria due to breeding zones for mosquitoes created by the wetland during rainy seasons; the drying of Lake Kanyaboli attributed to diversion of water for use by the Dominion Farms; water contamination by effluents discharged from the commercial farms, absence of proper inlet of water into Lake Kanyaboli (Figure 5); reduced rainfall due to climate change over the years; backflow of River Yala causing flooding and displacement of wetland residents; direct flow of Yala River water into Lake Namboyo causing flooding from its back flow; and intrusion into fish breeding zones by the fisher forks.

Yala Wetland environmental challenges by remotely sensed data (satellite images)

Information from the satellite images analysis corroborates some of the aforementioned findings from communities. Detailed photographic evidence of the condition of the wetland was not available prior to 1984, but the extent of changes that have occurred to the wetland in the last 40 years could be seen with reference to historic and current aerial and satellite images provided by Google Earth. The following images (Figure 2a to g) of various dates provide a valuable record of historic land use changes in the area. Figure 2a is an image of the wetland taken on 31 December 1984. The south-eastern plain below Lake Kanyaboli (the area now occupied by Dominion Farms) appears as partially reclaimed and cultivated. However, there is no evidence of the retention dyke which was built during the 1960’s separating Lake Kanyaboli and the middle area of wetland and much of the lake itself appears to be covered with either papyrus or floating vegetation.

Figure 2a shows the south-eastern plain below Lake Kanyaboli and the enlarged image (Figure 2b) shows the existence of parts of the retention and cutoff dykes, although these had fallen into disuse by the 1980s. However, the Yala River had been partially diverted at this time and flood water flowed both to Lake Kanyaboli and along the southern canal discharging into the middle swamp at a point close to Bulungo village (Figure 2c).

Detailed examination of the historic evidence (2001) shows that the southern diversion of the River Yala ended at a point to the north of the peninsula on which the village of Bulungo is situated (Figure 2d). The original course of the southern diversion canal can still be seen in Figure 2d with the current canal, realigned and reconstructed after 2003, marking the boundary between traditional farmland around Bulungo village and recent large scale reclamation.

These satellite images show very minimal change in the main characteristics of the Yala Wetland between 1984 and 1994, as revealed by a comparison of Figure 2a to c, however towards the end of this period the image suggests that revegetation has occurred across the lower part of the area now leased to Dominion Farms.

The wetland communities through focus group discussions, key informant interviews, community meetings and students’ essays, debates and artwork feedback showed the manifestation of key environmental issues and suggested how SEA and LUP should mitigate them in the final plan. This is shown in Table 3.

Multiple analysis of the historical, current and contextual information about the community participation in Yala Wetland developments to date thus revealed that the wetland ecosystem has varied and critical issues that need to be considered for its sustainable management. This requires management that is sensitive to accommodate local communities’ context and cultural belief systems. The historical and contextual understanding of Yala Wetland and environmental issues analyzed in this study were then used to shape the final SEA and LUP reports for the management of the wetland. Further, local communities and students were able to envision the future of Yala Wetland which informed the final LUP outcome.

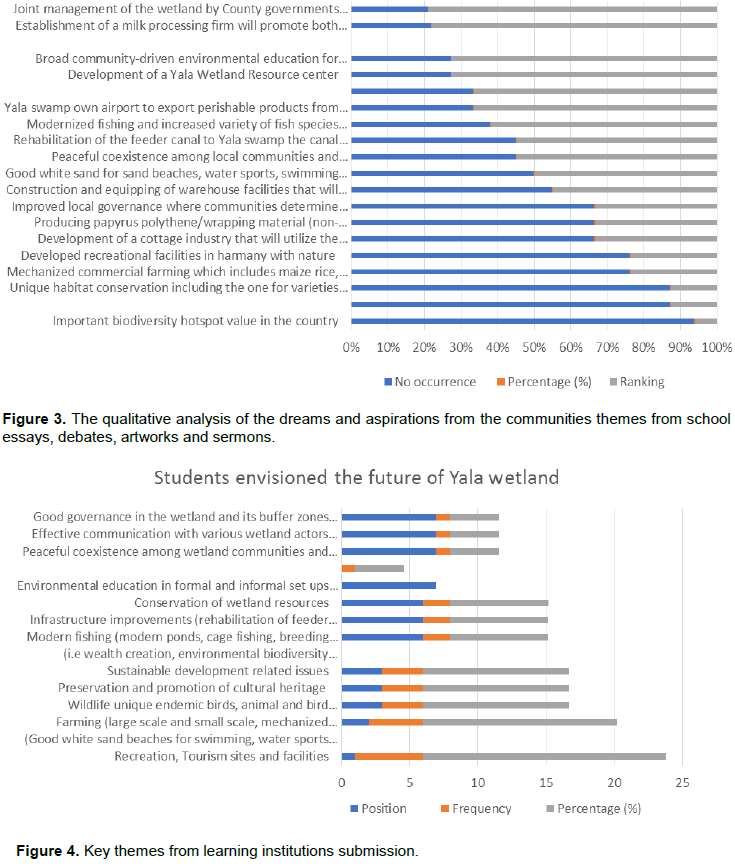

Envisioning/Communities dream of a future perfect Yala Wetland in 2066

The communities were asked to envision Yala Wetland in 2066 in their focus group discussions and community meetings. The content analysis data of the dreams and aspirations from the communities brought out a clear picture of what they would like the wetland to look like in 50 years’ time. The frequencies of emerging themes were: biodiversity conservation (8%); enforceable laws and regulations to protect the wetland (7%); mechanized commercial farming with robust extension system (7%); unique habitat conserved including the one for varieties butterflies (7%); and developed recreational and tourism facilities in harmony with nature (7%). The exhaustive list of the communities aspirations that shows the frequencies of issues mentioned in the FGDs that eventually informed final LUP is as shown in Figure 3.

Envisioning a future perfect Yala Wetland in 2066 by wetland communities

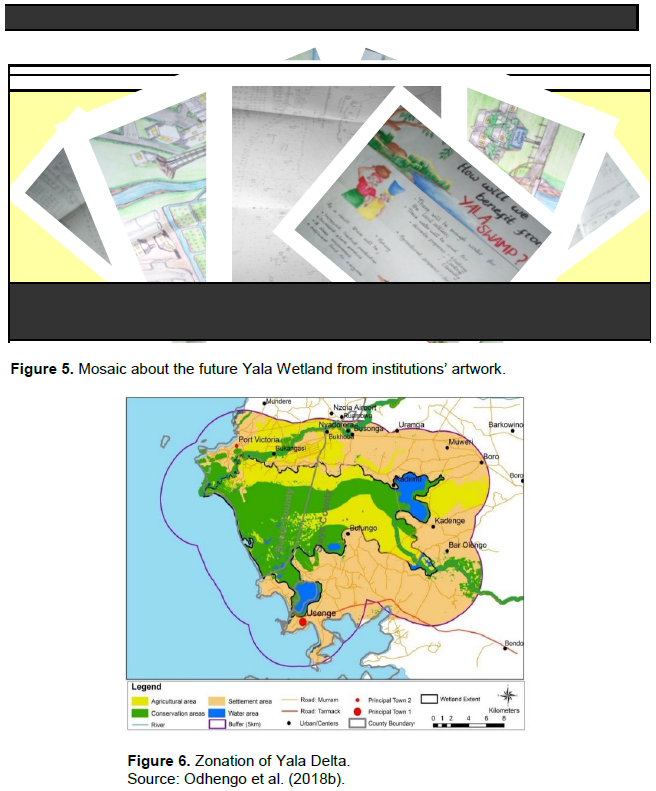

The results from primary and secondary schools, and post-secondary institutions on key environmental issues and their ranking for Yala LUP considerations that were analyzed from essays, artworks, and debates are as shown in Figures 4 and 5. Figure 5 is a creative fusion of various artworks submitted by students into one mosaic that captures their aspirations artistically. On these, the communities aspirations significantly informed the vision and mission and planning statements in the final Yala Wetland LUP.

Some of the students creatively envisioned Yala Wetland using artworks and these were further collapsed into the following mosaic (Figure 5).

The Yala Wetland communities used transformational learning methodologies to reflect and act upon their world in order to change it to future aspiration. This changed world view became the basis for their inputs in the Yala Swamp LUP. The Community Facilitator (CF) inducted the wetland communities on the application of opportunity-based view/lenses through appreciative inquiry methodology and empathy walk which they quickly adopted and used to generate their inputs into the plan. The broader wetland community representation through community facilitator intervention enabled local communities to envision, dream, and articulate their aspirations of the future Yala Wetland using possibility-based mindset and eventually provided for wider ownership for the sustainable Yala Wetland. All their perspectives were incorporated in the final SEA and LUP reports and depicted in the final Yala Land Use Plan (Figure 6).

Final Yala Delta land use plan

The planning process took over two years (2016-2018) and with enhanced community participation provided by the action research interventions as discussed, finally recommended three main land uses namely: conservation, agricultural and settlement areas as shown in Figure 6.

Governance framework for Yala Wetland ecosystems management

The local communities have participated in the management of the Yala Wetland in various ways alongside other actors. They have done this through their community-based organizations, through chiefs’ meetings/open public gatherings, religious groups/networks, schools and cooperative societies. The attendance of some of these meetings has been determined by the relationship between individuals and organizers of those meetings. Political players which included local members of parliament and civic leaders were found to dominate key decision making on the wetland as evidenced in the decision to lease part of the wetland to the Dominion Farms Limited, which was made solely by the political class through the then local authorities (county council and district development committees), without any reference to the local communities. Likewise, communities have been consulted without substantial stake in the management of Yala Wetland through existing community formations (CBOs), and religious groups.

This analysis reveals that there has been no Yala Wetland wide institutional framework where communities’ wetland ecosystem issues are discussed and channeled for decision making in the management of the wetland ecosystem.

Rather, small group community formations such as CBOs, sector specific groups that lack the larger wetland clout to influence key environmental decisions have been the norm. Instead, political players have dominated key decision making on the wetland ecosystem issues and decision done solely by the political class. This gap for community participation in the management of Yala Wetland ecosystem affairs has continued over time despite significant increase in wetland challenges. In order to remedy this, the wetland communities proposed a governance system that has wetland-wide representation, and provides a structure for communities’ participation at conservation areas zone of the wetland. It is named Yala Swamp Management Committee. This governance structure has been validated by the community representatives at the development of Yala Indigenous Community Conservation Areas Management Plan 2019-2029 in March 2020 (Figure 7). The 43 membership shown in Table 4 has been derived from various community groups representing different interests, namely County Village Natural Resource Land Use Committees (VNRLUCs), Inter-County ICCA steering committee, Yala Ecosystem Site Support Group members (YESSG), and Civil Society organizations (CSOs) guided by fair ecosystem and equity-based representation between Busia and Siaya counties and provides for 3 members co-option to bring some unique value addition to ICCA such as fundraising leverage. In addition, technical staff from the various county and national government sectors and other agencies (e.g. Agriculture, Fisheries, Tourism, Wildlife, etc.) will be co-opted in the committee as the need arises. The ICCA Management Committee shall provide strategic leadership, mobilize resources, and provide oversight on conservation areas’ programs implementation.

This governance structure has put wetland Communities at the core for managing conservation areas of Yala Wetland ecosystem as identified in the final LUP.

Proposed community committee member where the 43 positions will be shared based on fair representation and equity between Busia and Siaya counties

The Yala Swamp Management Committee members are drawn from the conservation area zone of the Yala Land Use plan initially, but other zones (that is, Settlement and Agricultural), would join too. The 10-point committee’s roles and responsibilities have been spelt out and are adequate to deliver their Yala Wetland conservation management plan 2019-2029 (in draft August 2020) when finally adopted. This proposed structure seeks to put the wetland communities at the core of conservation area zone management of the Yala Wetland, and is in line with relevant legislation (Wildlife Conservation and Management Act, 2013).

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

From the foregoing, the utilization of Yala Wetland resources has been partly informed by how the local communities perceive its formation. Consequently, improvements to sustainably manage the wetland ecosystem ought to factor the historical and contextual information. The Yala Wetland communities identified key environmental issues, their root causes and corresponding opportunities that LUP needed to address to ultimately manage Yala Wetland sustainably. The analysis also revealed existing gaps in the integration of community information and scientific information, disconnect between decision making and requisite scientific and practical evidence required to guide wetland management decision making, absence of community sensitive Yala Wetland wide institutional framework in planning and managing Yala ecosystem.

The study succeeded in integrating local communities’ vast knowledge and planning science information and proposed a governance structure and membership for the management committee that put communities at the centre of conservation in Yala Wetland, starting with community conservation areas. To overcome the implementation challenge, there is a secretariat led by a Community Facilitator to undertake day to day activities of implementing the conservation area management plan of the Yala Wetland. Also, there is the need for a strong, passionate and transformational leadership at the community level on wetland issues. All these have since been incorporated in the LUP processes and reflected in the final Yala Wetland land use plan. The study recommends the urgent need for systematic documentation and preservation of Yala Wetland local communities’ knowledge systems and subsequent use of it to manage Yala Wetland ecosystem.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

Note: This paper is part of Douglas Ouma Odero’s doctorate research thesis titled “Integrated Community and Participatory GIS in Management of Yala Wetland Ecosystem, Lake Victoria Basin, Kenya” at the Department of Environmental Monitoring, Planning and Management, School of Environmental Studies, University of Eldoret. The authors are grateful to the Yala Delta Land Use Plan Team, the University academics who contributed to this research and finally to the Yala wetland communities who were part of this action research. The authors acknowledge Retouch Africa Consulting (RAI) for financially supporting the research.

REFERENCES

|

Ampofo S, Ampadu B, Abanyie SK (2015). Landcover Change Patterns in the Volta Gorge Area, Ghana: Interpretations from Satellite Imagery. Journal of Natural Sciences Research 5(4): 2224-3186 (Paper): 2225-0921.

|

|

|

|

Aloo PA (2003). Biological Diversity of the Yala Swamp Lakes, with special emphasis on fish species composition in relation to change in L. Victoria Basin: Threats and conservation measures. Biodiversity and Conservation 12: 905-920.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Awange JL, Ogalo L, Baek O, Were P, Omondi P, Omute P, Omullo P, (2008). Falling Lake Victoria water levels: Is climate a contributing factor? Climate Change.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Awange JL, Obiero-Ong'ang'a (2001). Lake Victoria: Ecology, Resources, Environment. ISBN: 978-3-540-32574-1 (Print) 978-3-540-32575-8 (Online), John Reader (2001). Africa. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society. pp. 227-228. ISBN 0-7922-7681-7.

|

|

|

|

|

Babbie ER (2015). The practice of social research. 14th Edition. Boston, Massachusetts: Wadsworth Publishing.

|

|

|

|

|

Birdlife International (2018). Important Bird Areas Factsheet. Yala Wetland complex. Retrieved January 22, 2018, from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Cooke B, Kothari U (Eds.) (2001). The Case for Participation as Tyranny. Participation: The New Tyranny? London: Zed Books.

|

|

|

|

|

Cooperrider DL, Whitney D, Stavros J (2008). Appreciative inquiry handbook: For leaders of change. (2nd edition). Ohio: Crown Custom Publishing and Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

|

|

|

|

|

Chambers R (2006). Participatory Mapping and Geographic Information Systems: Whose Map? Who is Empowered and Who Disempowered? Who Gains and Who Loses? Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries 25(2): 1-11.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Department of the Environment, Transport and Regions (DETR) (2000). Public Participation in making local environmental decisions. The Aarhus Convention Newcastle Workshop Good Practice Handbook, London.

|

|

|

|

|

Doelle M, Sinclair J (2005).Time for a new approach to public participation in EIA: Promoting cooperation and consensus for sustainability. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 26:185-205.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dominion Farms (2003). The Environmental Impact Assessment Study Report. Siaya. Dominions Farms Limited.

|

|

|

|

|

Envertek Africa Consult Limited (EACL) (2015). Proposed sugarcane plantation and processing mill for dominion farms limited in Siaya county location: reclaimed section of Yala swamp on longitude 34.171380 east and latitude 0.022992 north in the flood plain of river Yala in Siaya and Bondo subcounties in Siaya county, Kenya. Environmental and social impact assessment (esia) study report. Dominion farms limited (DFL).

|

|

|

|

|

Dweck CS (2008). Mindset: the new psycholology of success. New York: Ballantine Books.

|

|

|

|

|

East Africa Natural History Society (EANHS) (2018). Balancing Conservation and Development in Yala Swamp. Posted on January 30, 2018.

|

|

|

|

|

Ekirapa AE, Kinyanjui HCK (1987). The Kenya soil survey. Ministry of Agriculture, National Soil Laboratories.

|

|

|

|

|

EMCA (2012). The Environmental Management and Co-Ordination Act, Chapter 387. Published by the National Council for Law Reporting with the Authority of the Attorney-General.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Friis-Hansen E, Duveskog D (2012). The Empowerment Route to Well-being: An Analysis of Farmer Field Schools in East Africa, World Development.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gichuki J, Maithya J, Masai DM (2005). Recent ecological changes in of Lake Sare, Western Kenya. In: (eds). Odada EO, Olago DO, Ochola W, Ntiba M, Wandiga S, Gichuki N, Oyieke H Proceedings of the 11th World Lakes Conference, Nairobi, Kenya. Vol II. Ministry of Water and Irrigation; International Lake Environment Committee (ILEC).

|

|

|

|

|

Government of Kenya (GoK) (1987). Yala Swamp Reclamation and Development Project: Inception Report'. The Government of Kenya and the Government of Netherlands. Lake Basin Development Authority.

|

|

|

|

|

Government of Kenya (GoK) (2010a). Constitution of Kenya, 2010.

|

|

|

|

|

Government of Kenya (GoK) (2010b). Schedule-Lake Kanyaboli National Reserve,Government Printer, Nairobi.

|

|

|

|

|

Government of Kenya (GoK) (2012a). The National Land Commission Act, 2012. Nairobi. Government Printer.

|

|

|

|

|

Government of Kenya (GoK) (2012b.) The County Governments (Amendment) Act, 2012.

|

|

|

|

|

Government of Kenya (GoK) (2015). The Environmental Management and Co-ordination (Amendment) Act, EMCA (2015). Retrieved May 10, 2015, from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Government of Kenya (GoK) (2020). The Public Participation Bill 2020. Nairobi. Government Printer.

|

|

|

|

|

Greene M (1995). Releasing the imagination: Essays on education, the arts, and social change. Jossey-Bass.

|

|

|

|

|

Hartley N, Wood C (2005). Public participation in environmental impact assessment: implementing the Aarhus Convention.Environmental Impact Assessment Review 25: 319-340.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

IAP2 (2008). International Association of Public Participation Public Participation Spectrum.

|

|

|

|

|

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (2016). SSC Antelope Specialist Group. (2016) Tragelaphus spekii. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T22050A50195827.

|

|

|

|

|

International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) (2018). Protected Planet Report. IUCN, Geneva, Switzerland.

|

|

|

|

|

IYSLP (2017). International Yearbook of Soil Law and Policy 2016.Springer Science and Business Media LLC.

|

|

|

|

|

JICA (1987). The Study of Integrated Regional Development Master Plan for the Lake Basin Development Area. Japan International Cooperation Agency.

|

|

|

|

|

Kansiime F, Saunders MJ, Loiselle SA (2007). Functioning and dynamics of wetland vegetation of Lake Victoria: an overview. Wetlands Ecology and Management, 15(6):443-451.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) (2010). Resource Mapping Lake Kanyaboli Ecosystem.

|

|

|

|

|

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) (2010). 2009 Population and Housing Census. Nairobi: Government Printer.

|

|

|

|

|

Kenya Wetland Forum (2006). Rapid assessment of the Yala Swamp wetlands. East African WildLife Society, Nairobi, Kenya.

|

|

|

|

|

Lake Basin Development Authority (LBDA) (1989). Reclaiming the Yala Swamp. Resources 1(1):9-11.

|

|

|

|

|

Lee N (2000). Reviewing the quality of environmental impact assessment in Africa. In Environmental Assessment in Developing and Transitional Countries, eds. Lee N, George C, Chichester: John Wiley and Sons.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lihanda M, Aseto O, Atera F (2003). Environmental Assessment Study Report of the Proposed Rice Irrigation Scheme at Yala Swamp - Socio-cultural and Economics Survey, Vol III.

|

|

|

|

|

Lillesand TM, Kiefer RW (1987). Remote sensing image interpretation. 2nd ed. Chichester and New York: John Wiley.

|

|

|

|

|

Liverman D, Moran EF, Rindfuss RR, Stern PC (Eds.) (1998). People and Pixels: Linking Remote Sensing and Social Science. Committee on the Human Dimensions of Global Change, National Research Council. Washington DC. National Academy of Sciences.

|

|

|

|

|

Luedeling E (2011). Climate Change Impacts on Crop Production in Busia and Homa Bay. Kenya World Agroforestry Centre.

|

|

|

|

|

Maclean IMD, Tinch R, Hassal M, Boar R (2003). Social and economic use of wetland resources: A case study from Lake Bunyonyi, Uganda. Centre for Social and Economic Research on the Global Environment, University of East Anglia (CSERGE), Working Paper ECM 03-09.

|

|

|

|

|

Michener V (1998). The Participatory Approach: Contradictions and co-option in Burkina Faso. World Development 26(12): 2105-2118.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mills GEW (2000). Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

|

|

|

|

|

Muoria P, Field R, Matiku P, Munguti S, Mateche E, Shati S, Odeny D (2015). Yala Swamp Ecosystem Service Assessment. Siaya and Busia County Governments.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Nasongo AAS, Zaal F, Dietz T, Okeyo-Owuor JB (2015). Institutional Pluralism, access and use of wetland resources in Nyando papyrus, Kenya. Journal of Ecology and the Natural Environment. 7(3): 56-71.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

NEMA (2016). Yala Swamp Integrated Management Plan (2016-2026): Enhancing Environmental Management through Devolved Governance. Nairobi: NEMA.

|

|

|

|

|

Neuman WL (1997). Social Research Methods: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches,3rd ed. Boston. MA: Allyn and Bacon.

|

|

|

|

|

Odero DO (2015a). Promoting Community Participation in Transboundary Natural Resource Management in Mt Elgon Ecosystem using Geographic Information Systems: Case study of Mount Elgon Regional Ecosystem Conservation Programme. Graduate Seminar Paper, University of Eldoret.

|

|

|

|

|

Odero DO (2015b). The Application of Remote Sensing in Community Participation for Managing Mt Elgon Transboundary Natural Resources: Case study of Mount Elgon Regional Ecosystem Conservation Programme. Graduate Seminar Paper, University of Eldoret.

|

|

|

|

|

Odhengo P, Matiku P, Muoria JK, Nyangena J, Wawereu P, Mnyamwezi E, Munguti S, Odeny D, King'uru W, Ashitiva D, Nelson P (2018a). Yala Delta Strategic Environmental Assessment. Siaya and Busia County Governments, Siaya and Busia.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Odhengo P, Matiku P, Muoria JK, Nyangena J, Wawereu P, Mnyamwezi E, Munguti S, Odeny D, King'uru W, Ashitiva D, Nelson P (2018b). Yala Delta Land use Plan. Siaya and Busia County Governments, Siaya and Busia.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Ogutu MA (1987a). Fisheries and fishing. Siaya District Socio-Cultural Profile. Ministry of Planning and National Development and Institute of Agricultural Studies, University of Nairobi, Republic of Kenya, Kenya. pp. 86-105.

|

|

|

|

|

Ogutu MA (1987b). Fisheries and fishing. Pages 86-105. In: Republic of Kenya (1987) Siaya District Socio-cultural Profile. Ministry of Planning and National Development and Institute of Agricultural Studies, University of Nairobi, Kenya.

|

|

|

|

|

Ondere LA (2016). Spatial-temporal changes of landcover types in response to anthropogenic dynamics in Yala Swamp, Siaya County, Kenya. Masters desertation, Moi University, Kenya.

|

|

|

|

|

Onywere SM, Getenga ZM, Mwakalila SS, Twesigy CK, Nakiranda JK (2011). Assessing the Challenge of Settlement in Budalangi and Yala Swamp Area in Western Kenya Using Landsat Satellite Imagery. The Open Environmental Engineering Journal 4:97-104.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Okello N, Beevers L, Douven W, Leentvaar J (2009). The doing and un-doing of public participation during environmental impact assessments in Kenya. Impact Assessment and Project Appraisal Journal 27(3):217-226.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Okungu J, Sangale F (2003). Water quality and hydrology of Yala wetlands. ECOTOOLS Scientific Workshop on Yala Swamp. Switel Hotel, Bondo, Kenya. 9th-10th December.Olsen (2008).

|

|

|

|

|

Otieno MN, Odenyo VOA, Okeyo JB (2001). The capabilities of multispectral Landsat TM for mapping spatial landscape characteristics of a tropical wetland. The case of Yala swamp, Kenya. In Proceedings of LVEMP, First Regional Scientific Conference 3rd-7th December 2001, Kisumu, Kenya.

|

|

|

|

|

Owiyo P, Kiprono BE, Sutter P (2014a). The Effect of DominionIrrigation Project on Environmental Conservation in Yala Swamp, Siaya District, Kenya. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101(39):13976-13981.

|

|

|

|

|

Panayotou T (1994). The economics of environmental degradation: Problems, causes and responses. In: Pattanayak, S.& Kramer, R. A. Pricing ecological services: Willingness to pay for drought mitigation in eastern Indonesia. Land Economics.

|

|

|

|

|

Raburu PO (2012). Conservation and rehabilitation of Kanyaboli wetland, Kenya. In Streever W.J (EDs). An International Perspective on Wetland Rehabilitation. Springer Science & Business Media, 6 December 2012 - Technology & Engineering pp. 167-172.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ramsar Convention Secretariat (2016). An overview of the Ramsar Convention.

|

|

|

|

|

Sandelowski M (1995). Sample size in qualitative research. Journal of Research in Nursing and Health 18(2):179-183.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sangale F, Okungu J, Opango P (2012). Variation of flow of water from Rivers Nzoia, Yala and Sio into Lake Victoria. Ministry of Environment and Natural Resources (LVEMP).

|

|

|

|

|

Semenov MA (2008). Simulation of extreme weather events by a stochastic weather generator. Climate Resources, 35(3): 203-212.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Simonit S, Perrings C (2011). Sustainability and the value of the 'regulating' services: Wetlands and water quality in Lake Victoria. Ecological Economics 70: 1189-1199.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Springate-Baginski O, Allen D, Darwall WRT (eds.) (2009). An Integrated Wetland Assessment Toolkit: A guide to good practice. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN and Cambridge, UK: IUCN Species Programme xv.

|

|

|

|

|

Stec S, Casey-Lefkowitz S, Jendroska J (2000). The Aarhus Convention: An implementation guide.Geneva:United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

|

|

|

|

|

Turner BL II. (1998). Frontiers of Exploration: Remote Sensing and Social Science Research., Pecora 13 Symposium, Human interaction with the Environment: Perspectives from Space (August 20-22, 1996, Souix Falls, SD) pp. 15-19.

|

|

|

|

|

Thenya T, Ngecu WM (2017). Dynamics of resource utilisation in a tropical wetland, Yala swamp, Lake Victoria basin- Statistical analysis of land use change. International Journal of Science Arts and Commerce 2(3):12-38.

|

|

|

|

|

Thomas D, Kariuki M, Magero C, Schenk A (2016). Local people and Tool For Action, Results and Learning prepared for Annie E. Casey Foundation.

View

|

|

|

|

|

van Dam AA, Kipkemboi J, Mazvimavi D, Irvine K (2014). A synthesis of past, current and future research for protection and management of papyrus (Cyperus papyrus L.) wetlands in Africa. Wetlands Ecology and Management 22(2): 99-114.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

van Heukelom ST (2013). Security: The controversy of foreign agricultural investment in the Yala Swamp, Kenya. Doctoral Thesis. Centre for International Security Studies, Business School University of Sydney.

|

|

|

|

|

World-Wide Fund (WWF) (2006). Community-based Natural Resource Management Manual. WWF.

|

|