History of Afar

According to Getachew (2001), Kebede (1994) and Trimingham (1952), Afar belong to the Cushitic language family along with the Somali and Oromo. Trimingham (1976) further purported that the Afars crossed the Bab-el Mendab and the Gulf of Aden into the peripheral areas of East Africa. Through the passage of time, despite the controversies on the dichotomy, Asahimara (reds) and Adohimara (whites) had begun to be considered as the two main groups of Afar people. Lewis (1994) and Trimingham (1952) are some of the most credited writers who basically wrote on this division. As far as areas occupied were concerned, Fekadu et al. (1984) as cited in Ali (2008) and Voelkner (1974) had asserted that the Upper Middle Awash Valley and Lower Awash Plain and Delta were under the influence and occupation of Adohimara and Asahimara branches respectively. Besides, despite the presence of different tribal confederacies and tribes of each main branch, Lewis (1994) acclaimed that they are not territorially distinct groups.

There are two different views on the division of Afar people into Asahimara and Adohimara dichotomies. Getachew (2001) stated the reason for the twofold nature of Afar people, the first view, is of course political developments, migration, population intermingling across different backgrounds as well as economic organizations; while the second view deals with distinct habitation. In line with this, the Asahimara were migrants from the coastal areas of the Red Sea and Gulf of Tadjoura to the land of Afar where they intermingled with the Adohimara group in the Awash Valley (Getachew, 2001).Furthermore, Ayele (1986) indicated that the Asahimara are descendents of Sheik Haralmais, who introduced Islamic faith to the Afar people; while the Adohimara are from the Ankala Derder. As result of this, descendents of Sheik Haralmais became the Asahimara (reds) and conquerors while the rest of the Afar people become Adohimara (whites), and the conquered.

On the other hand, Lewis (1994) stated that the Asahimara are people from the Ethiopian highlands who migrated and encroached to the hinterlands of Afar during the 16th century, and imposed their influence on the existing Afar tribes in Dankalia. In the meantime, due to frequent exposure as well as internal and external interaction that the Asahimara had, it was necessary that they formed their own Sultanate at Aussa (Getachew, 2001). According to the annals of history, the Afar triangle has been taken as the most strategic due largely to its location in entertaining the long distance caravan trade. As a result of this geographic advantage, according to Getachew (2001), the region is well remembered for frequent enthrone and dethrone of Sultanates.

The most traceable Sultanates, according to Dahilon (1985), were Rahyata (south of Assab), Biru (North east Tigray), Tadjoura (Ethio-Djibouti border), Gobaad (Djibouti) and Aussa (Afar). The evolutionary roots of Sultanates mentioned earlier (except Aussa) goes back to the Sultanate of Ankala with its center at Rahayto, present day Republic of Djibouti and Southern Eritrea (Getachew, 2001). Emphasizing this information, Trimingham (1952) and Lewis (1955) acclaimed that the Ankala tribe had played a significant role in defusing the other tribes, and were first referred to as “Afar” during the 13th century by an Arab geographic writer, Ibn Said. Hence, Ankala should be referred to as the first home land of ancient Sultanates of the Afar except Aussa.

The emergence of Aussa sultanate

As far as the history of Aussa Sultanate is concerned, the two different views that have been repeatedly discussed by historians are that they are immigrants who moved from Yambu Yemeni to Afar land and remnants of Adal Sultanate (Kebede, 1994). According to Cossins (1983), Yemeni Arabs who migrated to the Afar land were the ones to whom both history and legend gave credit for the formation of Aussa sultanate and for the commencement of crop cultivation. Contrarily, Aramis (2009) surmised that Aussa Sultanate was the historical heiress of the Muslim kingdom of Adal. Furthermore, Adou (1993) purported that while the Sultanate of Ifat was on the glimpse of its demise, the rival power had faced a fierce resistance. Amidst this, the fierce resistors were reported to have absconded deep to the east and protected the Sultanate of Adal with its center at Dakar.

The sultanate had declared its ascendancy after defeating the Christian High Land Kingdom at the battle of Shimbra Kure (Trimingham, 1976). As a matter of history, the Christian High Land Kingdom supported by the Portuguese army headed by Christopher Dagama over consummated and over maneuvered the army of Ahmad Gragn whereby the survivors were forced to retreat to the seat of the Sultanate that would soon been challenged by the Oromo population movement (Bahiru, 2002). Trimingham (1976) stated that the Afar themselves were responsible for the formation of the nomadic part of the Adal Sultanate; and at the same time a considerable number of Ahmed Gragn’s armies had also been recruited from.

Accordingly, Trimingham (1976) surmised that soon after the death of Ahmed Gragn and the collapse of his troops including armies from Afar, remnants of the Afar were forced to go back to the Afar desert in search of a place for permanent settlement and then be credited for the formation of the Aussa Sultanate. Consistently, Getachew (2001) asserted as the Aussa Sultanate had evolved from the wars of Ahmed Gragn and fear of the Oromo aggression. To ascertain stability and secure the Sultanate from the newly emerging threat, according to Bahiru (2002), remnants started to change the seat of the Sultanate to a place where the Oromo could not penetrate easily; and finally Aussa was chosen as the seat to rally the sultanate in the last quarter of the 16th century (Abir, 1968).

For further justification, Trimingham (1952) surmised that the Sultanate of Aussa came into existence in 1577, when Imam Muhammed Jasa moved his capital from Harar to Aussa. Hence, Imam Muhammed Jasa (family of Ahmed Gragn) was the one whom history remembered to shift the seat from Harar to Aussa basically by leaving his brother as Wazir, chief assistance, of Harar. The analysis of Kebede (1994), apparently, has seriously to do with the aforementioned justification since it purports the presence of different Afar tribes who are believed to have descended from Imam Salman II by whom the rule of the Sultanate in Aussa was established. These tribes are named as Harera or Derdera which is most probably coined from their origin Harar. Hence, the second view, on the formation of Aussa Sultanate, sounds is more accurate and widely supported by different writers; and it is congruent with the traditional interpretation of history (Kebede, 1994).

The Aydahiso dynasty and political power transfer in Aussa sultanate

The Sultanate of Aussa remained the strongest Sultanates in the Horn of Africa from 1577 to 1975 though there were ups and downs. The triangular strategic location advantage that Aussa had; and fertile soil and Awash River (suitable for agricultural production) as well as livestock production gave Aussa Sultanate a momentum to be considered strong enough than other sultanates (Dahilon, 1985; Kebede, 1994; Getachew, 2001). Once the sultanate had formed the Oasis of Aussa, the issues of leadership, administration and political chair were points of concern that has been followed by series of conflicts and frequent enthrone, and dethrone of Sultans from Yemen up to 1734. As earlier discussed, Imam Mohammed Jasa took the seat of the Sultanate at Aussa in 1577; and half a decade later, in 1583, he faced the first brutal raid and defeat by the Wara Daya Oromo intrusion where he lost his life (Trimingham, 1952).

Though struggle between the partisans was reported to have continued, Trimingham asserted that the Sultanate of Aussa was further joined by the freed men of Harar from the Imamates of Aussa, and being an independent city-state in 1647 under the rule of Emir Ali Ibn Daud. Hence, the problem of internal political strive coupled with the independency of Harar had paralyzed the fate of Aussa Sultanate, and be under the rule of cruel Imams of Yemen: Imam Salman I, Imam Ali, Imam Omar and Imam Salman II up to 1734, when the Aydahiso dynasty came to the scene (Kassim, 1982).

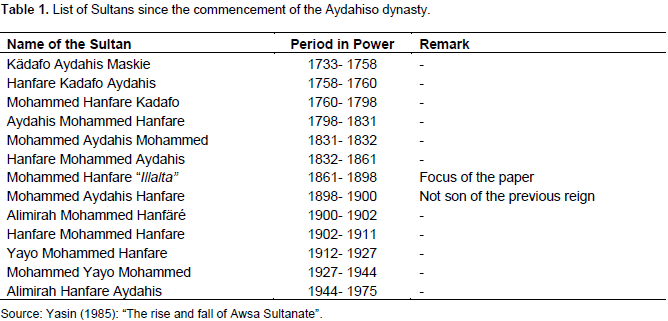

Aydahiso, according to Abir (1968), is a clan name from the Mudaito tribe and the Asahimara group; who were actually pastoralists engulfing towards the fertile land of Aussa. Since the commencement of the Sultan Kadafo leadership of the Aussa sultanate to the final emasculation of the sultanate under Sultan Alimirah II, all the sultans descended from the Aydahiso genealogy; and hence the Aydahiso dynasty. As a result of this, thirteen sultans were enthroned and dethroned to lead Aussa Sultanate where political power was solely patrimonial, from father to the eldest son; with the exception of Sultan Mohammed Hanfare “Illalta” (1861 to 1898) and his immediate successor. Table 1 presents the Sultans of Aussa Sultanate since the time of Aydahiso dynasty up to date.

Was Sultan Mohammed Hanfare “Illalta” a democratic sultan of Aussa?

Sultan Mohammed Hanfare “Illalta”, (the focus of this article) was the only one who had transferred his power not to his elder son but to his nephew on whom he had trust and believe to rule the Sultanate aptly. Due largely to this fact, a question aroused whether the sultan was democratic or not; as well as it instigates to consider him as he was farsighted and extraordinary in such a way that his vision could be realized not by bestowing his power to his elder son rather to his nephew whom he believe could run the sultanate the way he dreamt it would be or through merit based appointment.

The period of Sultan Mohammed Hanfare “Illalta” (1861 to 1898), internationally, was the time where European powers were pushing vigorously into the African interior; where the Sultanate of Aussa and its vicinity was supposed to be under the French colonial rule. During this period, still, Ethiopian neighbors particularly Egypt had launched a prolonged penetration deep into the Ethiopian hinterland. It was during this period that Mohammed Ra’uf Pasha of Egypt occupied the emirate of Harar including the ports of Zeila and Berbera.

Similarly, from the Tajura side (Djibouti), Muzinger launched an advance to the direction of Shewa though he was fiercely resisted and attacked by the Sultan himself at a place called Odduma in 1875 (Al-Shami, 2000). Furthermore, the most serious challenge also came from Massawa led by Colonel Arendrup (Danish Officer) and Arakil Bay to capture Adwa (Bahiru, 2002). All these conditions highlight that countries in general and individuals in particular were greedy with resources and power, and usually tried actually to elongate their hold on power. Due to what was perceived as the norm, it was thus unusual that Sultan Mohammed Hanfare “Illalta” did not use his power for greedy purposes.

Furthermore, his period of reign was contemporaneous with the period of Emperor Yohannes IV who pushed for Ethiopian unification basing religion as the point of unity. Even worse than this, Menelik, king of Shewa had a number of hidden agreements with Italians basically to earn military weapons by compromising Ethiopian territorial dignity, and then attain the title of king of kings. Before and after his coronation, Menelik had intended to expand his territory to the south, south east and south west regions of the country with the intention of controlling trade routes; where controlling Harar and then Aussa Sultanate was his dream.

After a fierce resistance and prolonged war, Menelik won the war against Emir Abdullahi of Harar at the battle of Chalanqo in 1887; which helped him to control the eastern commercial center of Harar and thereby gained full mastery of the long-distance trade route including Aussa (Bahiru, 2002). The Sultanate of Aussa had long been remained free of raids by the central government until invaded by Emperor Menelik II and became a tribute payer in 1895 with the pretext that the Sultanate becomes an ally with Italians (Trimingham, 1976; Lewis, 1994). One can simply deduce that political strive and succession problems are the most remembered political history of Ethiopia where political seat had been preceded by blood. Contrary to the patriarchy historical legacy that Ethiopia has held over time, condemning the decision of Sultan Mohammed Hanfare “Illalta” to transfer his political power to his nephew should be praised. This decision which stems from his democratic nature and farsighted outlook will be explored and analyzed in the course of this work.

At Sultanate level, Aussa had considerable wealth coupled with its triangular strategic location; fertile soil where agricultural production has also been practiced using Awash River (Dahilon, 1985); caravan trade, livestock and crop production (Getachew, 2001; and Kebede, 1994). The issue of power transfer was worsened in Aussa Sultanate where patriarchal lineage had been propagated to be followed till then. Breaking this historical legacy, Sultan Mohammed Hanfare “Illalta” had transferred his power to his nephew, Mohammed Aydahis Hanfare (1898 to 1900). There is no record of any other ruler before or after Sultan Mohammed Hanfare “Illalta” who broke the patriarchal power transfer. Thus, asking why he did all these while it was possible to scramble the resourceful area of Aussa and exploit the comparative geographical advantage that the Sultanate had seems rational; and better to differentiate him from his predecessors and successors. Given the above international, national and local political discussions, the authors of this paper have intended to answer whether Sultan Mohammed Hanfare “Illalta” was a democratic sultan or not.