ABSTRACT

This study aimed to perform a survey about medicinal plants used in the treatment of the hepatic dysfunction commercialized by healers (salespeople) in the São José Market - Recife/Pernambuco and São Joaquim Street Market in Salvador/Bahia - Brazil. The place to obtain them, preparation methods and used parts of the medicinal plants, knowledge about plants, age and gender of the healers were also investigated. Eleven semi-structured interviews were performed on the healers in the São José Market. The most cited species was Croton rhamnifolioides (33.3%), 100% of the healers bought the plants, 100% indicated the preparation of teas, 85.7% the use of the leaves; 45.5% obtained knowledge about medicinal plants through experience with sales, with an average age of 42.8 years, 54.5% were male and 44.5% were female. On the other side of the São Joaquim Street Market, six interviews were performed. Vernonia condensata had 50% of citations, 100% of the healers bought the plants, 100% indicated the preparation of teas, 60% the use of leaves; 83.3% learned through experience with sales, and had a mean age of 39.5 years, 54.5% were male and 44.5% were female. This study may contribute to a better use of these resources by the people and useful in the registration and cataloging of information about medicinal plants.

Key words: Croton, ethnobotany, liver, Vernonia.

Free markets and fairs are responsible for maintaining and propagating, through the healers, the empirical knowledge about the diversity of resources from medicinal plant species (Monteiro et al., 2010). The healers, also known as herbalists, herb people or herbs handling community, despite their low education, act as health professionals and have become important characters in the rescue of knowledge about the use of medicinal plants passed through generations (Amorozo, 2002). The healers’ knowledge can provide important data for new scientific discoveries and may lead to new knowledge about the therapeutic properties of plants (Simões, 1998). Thus, cataloging and correctly recording information about the use of medicinal plants of proven therapeutic value is fundamental for the Brazilian herbal medicine (Accorsi, 1992). Among the main problems caused by the indiscriminate and prolonged use of medicinal species are allergic reactions and toxic effects on several organs (Carlini, 2014). Therefore, it is very important to educate the public about the proper use of plants and natural medicines. Thus, research on medicinal plants, including ethnopharmacological studies, can contribute to better use of these resources by the population, but also bring knowledge of new and effective drugs to combat various ills (Amorozo and Gély, 1988).

Recently, the National Health Surveillance Agency (ANVISA) published a resolution creating registry for traditional herbal products and regulating herbal medicines, particularly those that are derived from medicinal plants (ANVISA, 2014). Medicinal plant is defined as any plant containing, in one or more of its organs, active ingredients or precursor substances that can be used for therapeutic purposes widely applied by alternative medicine (Amorozo, 2002). Probably, the use of plants in disease control is as old as man. About 3000 years before Christ, the Chinese have used and cultivated herbs, which today are still used efficiently both in popular medicine, such as laboratories of pharmaceutical products (Rodrigues et al., 2001). The use of medicinal plants is a common habit among the population and, currently, the interest in the use and trade of medicinal plants and herbal products in Brazil has increased. According to the World Health Organization, millions of people rely on traditional medicine to meet their primary health care needs (WHO, 2013). Within this context, an ethnobotanical survey was performed about medicinal plants used in the treatment of liver dysfunction traded by healers in public markets of Recife city in the State of Pernambuco and Salvador city in state of Bahia - Brazil. The sites where plants were obtained from, preparation methods and the parts of the plants being used, as well as the knowledge of plants, age and gender of the healers were also investigated.

Study area

This study was conducted from November, 2013 to April, 2014 in two public markets in the Northeast: São José Market (Figure 1A) located in the city of Recife/PE and São Joaquim Street Market (Figure 1B) located in Salvador/BA.

Data collection

Two methods were used for the interviews: the application of semi-structured questionnaires (Santos et al., 2012) seeking for a standard scheme on approaching the respondents and the free-listing technique, which consists on asking informants to list important events in relation to the subject under investigation (Azevedo and Coelho, 2002). Eleven interviews were conducted with healers from São José Market and six interviews with healers from São Joaquim Street Market. This work covered issues such as: major plants sold to treat liver dysfunction, site acquisition, preparation methods and parts used in medicinal plants, knowledge of plants, age and gender of the healers.

Data analysis

Data analysis was done with the database of information from interviews; and the botanical nomenclature in use is in accordance to The plant list (2013).

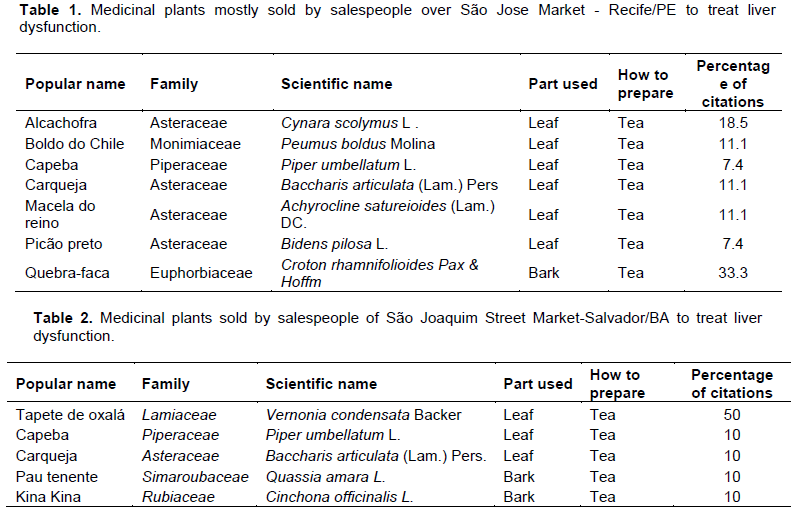

Based on the technque of free-listing interviews, the healers were encouraged to cite the medicinal plants used to treat liver dysfunction that are traded in São José Market (Table 1) and São Joaquim Street Market (Table 2). Among the species cited in São Jose Market - Recife/PE we found Artichoke (Cynara scolymus), Artemisia (Artemisia vulgaris), Boldo do Chile (Peumus boldus), Capeba (Piper umbellatum), Carqueja (Baccharis articulata), Fig leaf (Ficus carica), Losna (Artemisia absinthium), Marcela do Reino (Achyrocline satureoides), Pau pereira (Platycyamus reginelli), Picão Preto (Bidens pilosa), Quebra-faca (Croton rhamnifolioides), Quebra pedra (Phyllanthus niruri) and Uxi amarelo (Endopleura uchi). The species with the highest number of citations were: Alcachofra (C. scolymus) 18.5%, Boldo do Chile (P. boldus) 11.1%, Capeba (P. Umbellatum) 7.4%, Carqueja (B. articulata) 11.1%, Macela do reino (A. satureioides) 11.1%, Picão preto (B. pilosa) 7.4% and Quebra-faca (C. rhamnifolioides) 33.3%, as expressed in Table 1.

In São Joaquim Street Market /BA, the following plants were cited for the treatment of liver treat disorders: Tiririca de Babado/Carqueja (B. articulata), Capeba (P. Umbellatum), Boldo/Tapete de Oxalá (Vernonia condensata), Pau tenente (Quassia amara L) and Kina-Kina (C. officinalis) (the species that had the highest number of citations was V. condensata, popularly known as Falso Boldo or Tapete de Oxalá. Q. amara popularly known as Pau tenente got 10% of citations. Cinchona officinalis, popularly known as Kina Kina had 10% of citations.

Regarding the origin of medicinal plants traded in São Jose Market - Recife/PE and São Joaquim Street Market/BA, it was verified that 100% of the healers bought the plants. Healers of São José Market/PE said that plants came from cities such as Gravatá, Bezerros and Caruaru, and others said they bought it at the Santa Rita pier Street Market. As for the healers of the São Joaquim Street Market/BA, they obtained it from the cities of Alagoinha, Amargosa, Aracaju, Feira de Santana, Simões Filho, Candeias and Northeastern Complex. Therefore, none of the respondents said in cultivating the medicinal plants, the market became dependent on middlemen.

Tea was the predominant form of preparation, both in São Jose Market - Recife/PE (100%) and in São Joaquim Street Market/BA (100%). Leaves were the parts of the plants most indicated by healers. In São José Market/PE there were 85.7% of citations while in the São Joaquim Street Market/BA, leaves occupied about 60% of the citations.

As for the acquisition of knowledge about medicinal plants and the profile of traders as expressed in Figure 2, according percentage of interviewees, 45.5% of the healers of the São José Market/PE stated they purchased the plants based on their own experience in daily sales of medicinal plants, 36.4% based on family tradition (knowledge being handed down through generations) and 18.1% learned about it on Herbology courses (Figure 2A). In comparison, in São Joaquim Street Market/BA, 83.3% of the healers learned about these plants on the daily sales of medicinal plants and 16.7% obtained the knowledge from family tradition (Figure 2B).

The age of healers from the São José Market / PE was between 27 to 65 years (Figure 3A) with an average of 43.8 years of age, being 54.5% males and 45.5% females (Figure 3B). In São Joaquim Street Market/BA, the age ranged between 25 to 58 years (Figure 4A), with an average of 39.5 years, with 83.3% males and 16.7% female (Figure 4B).

Among the species with the highest number of citations in São José Market - Recife/PE are the Artichoke (C. scolymus) with 18.5%, which has an antioxidant potential that protects liver cells from oxidative stress (Özlem, 2013), Boldo do Chile (P. boldus) with 11.1%, presenting a significant hepato-protection in a model of hepatotoxicity induced by carbon tetrachloride in mice (Lanhers et al., 1991) and P. umbellatum, popularly known as Capeba, with 7.4%. Nwozo et al. (2012) in a study with Piper guineense, a species belonging to the same family as P. umbellatum, found that the species possessed potent antioxidants that can alleviate liver damage associated with chronic alcohol exposure, based on the animal model with rats.

B. articulate, with 11.1% of citation, is popularly known as carqueja. Published studies validated its digestive and antacid (Gamberini et al., 1991), antiulcer and anti-inflammatory properties (GamberiniI et al., 1991; Gené et al., 1996).

The A. satureioides species, popularly known as Marcela do reino, with 11.1% of citations, has uses for stomach treatment and headache purposes as proven by Gonzalez et al. (1993), Panizza (1998) and Simões et al. (1988). Picão Preto (B. pilosa) obtained 7.4% of citations. According to Suzigan et al. (2009), the aqueous extract of B. pilosa protects liver against damage induced by chronic obstructive cholestasis in young rats.

Quebra-faca (Croton rhamnifolioides) which has 33.3% of citations, has proven efficiency on its antimicrobial (Costa et al., 2013) and cytotoxic (Santos, 2013) activities. No studies have been reported in the literature about its efficacy in liver dysfunction.

In São Joaquim Street Market in Salvador/BA, the species that had the highest number of citations was the V. condensata, popularly known as "falso-boldo” or “Tapete de Oxalá”. According to Silva et al. (2011), this species has anti-nociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities. Silva et al. (2013) confirmed the antioxidant effect in ethanol extract and fractions of V. condensata. Frutoso et al. (1994) found that the species had an analgesic and anti-ulcer activity. Q. amara, also known as Pau tenente, got 10% of citations. According to Husain et al. (2011) it possessed potential in the treatment of diabetes, while C. officinalis, known as Kina Kina (10% of citations) showed a protective effect against liver cancer in rats (Sabah, 2010). No studies have been reported in the literature on the efficacy of Q. amara and C. officinalis in liver dysfunction.

In our results concerning the origin of medicinal plants, it was found that all healers (100%) bought plants. These results differed from the ones found by Heiden et al. (2006), where eight of the respondents (61.5%) collected the plants they sold. In São José and São Joaquim Street Markets, the predominant form of plant utilization was the tea. The infusion and decoction called tea was referred to by Simões et al. (1988). According to Merzouki (2000), the prevalence of infusion and decoction was related to three factors: they were cheap, fast and easily-accessible treatments. The decoction (boiled tea) was mainly indicated in preparations made ​​from bark, stems, roots and seeds, while the infusion was indicated for parts such as leaves, stems, flowers and also aromatic herbs (Matos, 2000). The leaves were the most indicated plant parts mentioned by the healers. As in São Jose Market and São Joaquim Street Market, leaves were also considered the most used part of the plant for the preparation of teas, mentioned in various papers on medicinal plants (Pilla et al., 2006; Jesus et al., 2009; Cunha et al., 2011).

With respect to knowledge acquisition about the plants, it was shown that such knowledge arises from the experience of salespeople, on a daily basis, from ongoing family tradition and also from herbal medicine. Our results corroborated with studies from Tresvenzol et al. (2006) who also found that some respondents obtained knowledge by consulting books on the subject and taking courses. França et al. (2008) noted that respondents obtained knowledge with the everyday practice on selling plants in their workplace. Brito and Senna-Valle (2011) also identified that much of the knowledge about the medicinal plants was transmitted over the years by parents and grandparents, observing a cultural heritage on medicinal plants.

With regards to the age of the healers, there was a mean age of 42.8 and 39.5 years; regarding gender, 54.5% of male and 45.5% of female healers was observed. Similar results were shown by Miura et al. (2007) and Alves et al. (2007). However, some studies have found a different situation (França et al. 2008) or even an equitable distribution of genders (Alves et al., 2008). This fact may be associated with the cultural aspects, as in some social groups women tend to perform activities related to the domestic sphere. In different regions, a similar age distribution was observed (Araujo et al., 2003; Alves and Rosa, 2007; Miura et al., 2007). Two profiles of sellers were recognized by Mendes (1997): the elder, which always exercised this profession; and the younger, who before now, had other activities, and who chose to sell herbs as an alternate means of survival, since the use of these herbs has often been passed on by their relatives.

The financial support received from Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior CAPES is acknowledged.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Accorsi WR (1992). Apresentação. In: Vieira LS. Manual de plantas medicinais (A farmácia de Deus). 2nd ed. São Paulo: Agronômica Ceres. P 347.

|

|

|

|

Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária ANVISA (2014). RDC N° 26, de 13 de Maio de 2014 [Internet]. Brasília: Health Ministry – Brazil. 34p.

|

|

|

|

|

Alves RRN, Rosa IML (2007). Biodiversity, traditional medicine and public health: where do they meet? J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 3:1-9.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Alves RRN, Silva AAG, Souto WMS, Barboza RRD (2007). Utilização e comercio de plantas medicinais em Campina Grande, PB, Brasil. Rev. Eletr. Farm 4:175-198.

|

|

|

|

|

Alves RRN, Silva CC, Alves HN (2008). Aspectos socioeconômicos do comercio de plantas e animais medicinais em áreas metropolitanas do Norte e Nordeste do Brasil. Rev. Biol. Ciênc Terra 8:181-189.

|

|

|

|

|

Amorozo MCM (2002). Uso e diversidade de plantas medicinais em Santo Antônio do Leverger. Acta Bot. Bras. 16:189- 203.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Amorozo MCM, Gély AL (1988). Uso de plantas medicinais por caboclos do baixo Amazonas, Barcarena, PA, Brasil. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi, Série Botânica 4(1):47-131.00

|

|

|

|

|

Araujo TM, Brito CR, Aguiar MCRD, Carvalho MCRD (2003). Perfil socioeconômico dos raizeiros que atuam na cidade de Natal (RN). Infarma 15:77-79.

|

|

|

|

|

Azevedo SK, Coelho MFB (2002). Métodos de investigação do conhecimento popular sobre plantas medicinais. In: Rodrigues AG, editors. Plantas medicinais e aromáticas: etnoecologia e etnofarmacologia. Viçosa: UFV/Departamento de fitotecnia. 320p.

|

|

|

|

|

Brito MR, Senna-Valle L (2011). Plantas medicinais utilizadas na comunidade caiçara da Praia do Sono, Paraty, Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Acta Bot Bras 25(2):363-372.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Carline E (2014). Entre conhecimento popular e cientifico. HTTP://www.comciencia.br. Acesso em: fev.

|

|

|

|

|

Costa ACV, Melo GFA, Madrugada MS, Costa JGM, Junior FG, Neto VQ (2013). Chemical composition and antibacterial activity of essential oil of a Croton rhamnifolioides leaves Pax & Hoffm. Ciênc Agrárias 34:2053-2864.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cunha AS, Bortolotto IM (2011). Etnobotânica de Plantas Medicinais no Assentamento Monjolinho, município de Anastácio, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brasil. Acta Bot. Bras. 25(3):685-698.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

El-Naggar SMM (2010). Study on the Effect of Cinchona officinalis in the Protection of Kidney from Cancer. J. Genet. Eng. Biotechnol. 8:15-27.

|

|

|

|

|

França ISX, Souza JA, Baptista RS, Britto VRS (2008). Medicina popular: benefícios e malefícios das plantas medicinais. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 61:201-208.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Frutoso VS, Gurjao MRR, Cordeiro RSB, Martins MA (1994). Analgesic and anti-ulcerogenic effects of a polar extract from leaves of Vernonia condensate. Planta Med. 60(1):21-5.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gamberini MT, Skorupa LA, Souccar C, Lapa AJ (1991). Inhibition of gastric secretion by a water extract from Baccharis triptera, Mart. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 86:137-139.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gené RM, Carta-a C, Adzet T, Marin E, Parella T, Ca-igueral S (1996). Anti-inflammatory and analgesic activity of Baccharis trimera. Identification of its active constituents. Planta Med. 62(3):232-235.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gonzalez A, Ferreira F, Vázquez A, Moyna P, Paz EA (1993). Biological screening of Uruguayan medicinal plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2:217-220.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Heiden G, Barbieri R, Stumpf ERT (2006). Considerações sobre o uso de plantas ornamentais nativas. Rev. Bras. Hortic. Ornam. 12:2-7.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Husain GM, Singh PN, Singh RK, Kumar V (2011). Antidiabetic Activity of Standardized Extract of Quassia amara in Nicotinamide–Streptozotocin-induced Diabetic Rats. Phytother. Res. 25:1806-1812.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jesus NZT, Lima JCS, Silva RM, Espinosa MM, Martins DTO (2009). Levantamento etnobotânico de plantas popurlamente utilizadas como antiúlceras e anti-inflamatórias pela comunidade de Pirizal, Nossa Senhora do Livramento- MT Brasil. Rev. Bras. Farmacogn. 19:130-139.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lanhers MC, Joyeux M, Soulimani R, Fleurentin J, Sayag M, Mortier F, Younos C, Pelt JM (1991). Hepatoprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of a traditional medicinal plant of Chile, Peumus boldus. Planta Med. 57:110:115.

|

|

|

|

|

Matos FJA (2000). Plantas medicinais: Guia de seleção e emprego de plantas usadas em fitoterapia no nordeste do Brasil. 2nd ed. Fortaleza: Imprensa Universitária-UFC.

|

|

|

|

|

Mendes M (1997). Erveiros dos nossos mercados: uma mostra. Comissão Maranhense de Folclore. São Luis: Editora Boletim;

|

|

|

|

|

Merzouki A, Ed-Derfoufi F, Mesa JM (2000). Contribution to the knowledge of Rifian traditional medicine. II: Folk medicine in Ksar Lakbir district (NW Morocco). Fitoterapia 71:278-307.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Miura AK, Lowe TR, Schinestsck CF (2007). Comércio de plantas medicinais, condimentares e aromáticas por ervateiros da área central de Pelotas - RS: estudo etnobotânico preliminar. Rev. Bras. Agroecol. 2:1025-1028.

|

|

|

|

|

Monteiro JM, Araujo EL, Amorim ELC, Albquerque UP (2010). Local Markets and Medicinal Plant Commerce: A Review with Emphasis on Brazil. Econ. Bot. 64:352-356.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nwozo SO, Ajagbe AA, Oyinloye BE (2012). Hepatoprotective effect of Piper guineense aqueous extract against ethanol-induced toxicity in male rats. J. Exp. Integr. Med. 2(1):71-76.

|

|

|

|

|

Panizza S (1998). Plantas que curam (cheiro de mato). 15th ed. São Paulo: Ibrasa 279p.

|

|

|

|

|

Pilla MAC, Amorozo MCM, Furlan A (2006). Obtenção e uso das plantas medicinais no distrito de Martim Francisco, município de Mogi - Mirim, SP, Brasil. Act Bot. Bras. 20:789-802.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rodrigues VEG, Carvalho DA (2001). Levantamento etnobotânico de plantas medicinais do domínio cerrado na região do Alto Rio Grande. Ciênc Agrotec. 25:102-123.

|

|

|

|

|

Santos LML, Santana ALBD, Nascimento MS, Sousa KMO (2013). Avaliação do potencial alelopático de Croton blanchetianus Baill e Croton rhamnifolioides Pax e K. Hoffm. sobre a germinação de Lactuca sativa L. Rev. Biol. Farm. Campina Grande/PB 9:1-6.

|

|

|

|

|

Santos MM, Nunes MGS, Martins RD (2012). Uso empírico de plantas medicinais para tratamento de diabetes. Rev. Bras. Planta Med. 14:327-334.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Silva JB, Temponi VDS, Fernandes FV (2011). New approaches to clarify antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory effects of the ethanol extract from Vernonia condensata leaves. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 12:8993-9008.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Silva JB, Temponi VDS, Gasparetto CM, Fabri RL, Aragão DMO, Pinto NCC, Ribeiro A, Scio E, Vieira GV, Sousa OV, Alves MA (2013). Vernonia condensata Baker (Asteraceae): A promising source of antioxidants. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2013:9

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Simões CMO (1998). Plantas da medicina popular do Rio Grande do Sul. 5th ed. Porto Alegre: Editora da Universidade/UFRGS; 173p.

|

|

|

|

|

Suzigan M, Battochio APR, Coelho KLR, Coelho CAR (2009). An acqueous extract of Bidens pilosa L. protects liver from cholestatic disease: experimental study in young rats. Acta Cirurgica Bras. 24:347-352.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

The Plant List (2013). [internet] Londres: Version 1.1. 2013. Available at: http://www.theplantlist.org.

|

|

|

|

|

Tresvenzol LM, Paula JR, Ricardo AF, Ferreira HD, Atta DT (2006). Estudo sobre o comércio informal de plantas medicinais em Goiânia e cidades vizinhas. Rev. Eletr. Farm. 3:23-28.

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (WHO) (2013). (CH), Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014-2023. Genebra 76p.

|

|