The international community perceives Sudan as extremely corrupt and all available data and country reports indicate persistent, widespread and endemic forms of corruption, permeating all levels of society (Transparency International, 2012). In 2015 Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index (CPI) which ranks countries based on how corrupt their public sector is perceived to be, ranked Sudan 165 out of 168 countries surveyed. While in 2016, Sudan ranked 170 out of 176 countries.

According to the latest CPI in 2017, Sudan is the 5

th most corrupt country out of 180 countries that survived around the world. On a scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean), the Corruption Perception Index for 2016 marked Sudan 16.

Although corruption is generally inefficient and is disapproved of by the public, the widespread nature of it in Sudan suggests that corrupt behaviour may become a norm. The 2016 Transparency International Global Corruption Barometer states that about 61% of surveyed Sudanese think corruption in the country has increased

during the past two years. According to the 2016 Transparency International Global Corruption Barometer, one of the reasons why people tend not to report corruption in Sudan is because it is common and everyone is engaged in it.

The country also performs extremely poorly in controlling corruption. Sudan has a legal anti-corruption framework in place but faces major implementation challenges in practice (Transparency International, 2012). Beneficiaries—including the top leadership—tend to slow or block any anti-corruption initiative. According to the 2016 World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators, Sudan scored only -1.5 in its control of corruption [estimate of governance ranges from approximately -2.5 (weak) to 2.5 (strong)].

Although corruption is common in many economies in the world, its impact is greater on fragile economies like Sudan. A lot of revenue has been lost and continues to be lost through corruption in the country. Security and sustainability of economic growth are increased by effective anti-corruption efforts and regulation. Sudan is not going to achieve its goal for economic recovery given the current level of corruption that literally bans the country's development through all means and at all levels.

In terms of the clear, wide spread of corruption in Sudan, it is surprising that recently almost no studies have addressed this area. Kameir and Kursany (1985) studied and analysed corruption in Sudan during the eighties. They called corruption a ‘fifth’ factor of production since it had become a major source of income generation at that time. Bearing in mind that since that time there has been no serious attempt to curb corruption in the country, it has become an infinite dilemma.

This paper conducts a descriptive and a theoretical analysis of corruption in Sudan. It addresses the following research questions: (1) What are the possible causes of the widespread of corruption in Sudan and, (2) Given these causes what are the possible remedies to the problem of corruption in the country?. The aim of the paper is to functionally outline the causes and impact of corruption and to identify the possible means and aims of anti-corruption efforts.

The rest of this study is organized as follows; section two defines corruption and states its types. Section three presents the diagnostics of corruption in Sudan. Section four encompasses the causes of the wide spread of corruption in the country. Section five discusses the need to fight against corruption by highlighting its negative impact on the economy and society. Section sex presents other countries' experiences in fighting corruption. Section seven suggests a holistic approach to fight against corruption in Sudan. Section eight concludes the study.

Definition and types of corruption

Corruption is generally defined as ‘the use of power for profit, preferment, or prestige, or for the benefit of a group or a class, in a way that constitutes a breach of law or of standards of high moral conduct’ (Gould and Kolb, 1946, p. 142). It is also defined as ‘the use of public resources to further private interests’ (Sumner, 1982). The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) defines corruption as ‘the misuse of public power, office or authority for private benefit, through bribery, extortion, influence peddling, nepotism, fraud, speed money or embezzlement’ (UNDP, 1999, p. 7).

These definitions include but are not limited to: embezzlement, fraud, unofficial payments (bribes, speed money), using contacts and nepotism, cronyism and patronage, misuse of public resources for personal gains, misuse of power/position for personal gains and discrimination.

In an average Sudanese citizen's mind, corruption is not as this definition might suggest. While Sudanese people disapprove of corruption, they do tolerate other forms of corruption. That’s because in most countries where there is at least some corruption, there seems to be an acceptance of the ‘petty’ corruption (Jain, 2001).

Types of corruption

Corruption is generally classified into two broad categories that are: grand and petty corruption. In this study corruption is classified as follows:

Grand corruption

This includes corrupt politicians and legislators (in parliament) who aim to maximize their own interests. It also includes corruption in the justice system. This type of corruption may have the most serious consequences on a society; the corrupt political elite can change either the national policies or the implementation of national policies to serve its own interests at some cost to the populace (Jain, 2001). While corrupt politicians tend to maximize their own interest, they tend to create corrupt legislators and judges. The reason for that is to satisfy ruler desire to foster loyalty through patronage (Bonga et al., 2015). The judiciary system is a focal point to reduce corruption and promote the rule of law; that is why this study considers corruption in the judiciary system as a form of grand corruption.

Political corruption affects everyone directly or indirectly. Elected politicians and political parties are expected to act in the public interest, thus their greed can cause enormous damage (Takács et al., 2011).

Petty corruption

Petty corruption includes corrupt acts of the appointed bureaucrats, police, and public servants in their dealings with either their superiors (the political elite) or with ordinary citizens. According to Asongu (2013), it involves petty bribery and involves opportunistic individuals or small groups.

Diagnostics for the high corruption level in Sudan

This section discusses some diagnostics that triggers the high level of corruption in the country.

Political corruption

Sudan’s legislature as well as by the Supreme Audit Institution are fairly weak. In addition, the Parliament does not have the power to amend the executive budget proposal, nor does it have sufficient time to discuss and approve the budget (Transparency International, 2012). According to Transparency International (2012), major parts of the government budget are allocated to military spending. In addition budget processes are opaque, creating fertile grounds for financial mismanagement and embezzlement of public resources.

Judiciary system

Sudan's judiciary system is not independent and is subject to various forms of political interference; thus, it is ineffective. According to Global Integrity (2013), many independent sources raised objections and pointed to involvement in corruption by senior-level politicians and civil servants, but no investigations were formally undertaken while these people were still in office. Business Anti-Corruption Portal (2016) states that corruption in the Sudanese judicial system is a high risk for investors, both in the form of petty corruption as well as in the form of political interference. According to Freedom House (2016), while lower courts in Sudan provide some due process safeguards, higher courts are subject to political control.

Bribery

The populace may be required to bribe bureaucrats either to receive a service to which they are entitled or to speed up a bureaucratic procedure. In some cases, a bribe may even provide a service that is not supposed to be available (Jain, 2001). In Sudan, the only way to build a business seems to involve paying unofficial payments. Ordinary citizens cannot seem to get quality public service without providing a gift or paying bribes. The 2016 Transparency International Global Corruption Barometer states that 48% of the surveyed Sudanese who came into contact with a public service in the past 12 months said they paid a bribe.

Government budget

Gupta et al. (2001) state that there is a correlation between higher corruption and higher military spending; that is, the ratio of military spending to GDP and government expenditures is associated with corruption. Kameir and Kursany (1985) mention that corrupt governments need to protect their power, money and its accumulation; thus, they spend a huge part of the country’s budget on policing, security and the army.

According to Transparency International (2012) in Sudan major parts of the government budget are allocated to military spending, and this situation has persisted beyond the signature of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA). According to Global Integrity (2006) military budgets are not disclosed in Sudan and large amounts of funds are secretively used by the Presidency for ‘classified security operations’. In addition, the Ministry of Finance allegedly does not have records of expenditures of presidential, security and defense affairs. In 2013, Global Integrity stated that citizens lacked sufficient information on the budget from the government.

Transparency

Lindstedt and Naurin (2006) investigate and confirm, with cross-national data, the assertion that making political institutions more transparent may be an effective method for combating corruption. In Sudan the government provides the public with scant information on the government’s budget and financial activities, making it virtually impossible for citizens to hold the government accountable for its management of public money (Corruption and anti-corruption in Sudan, 2012). The military budgets are not disclosed. In addition the Ministry of Finance allegedly does not have records of expenditures of presidential, security and defense affairs (Transparency International, 2012).

Human rights

The consequences of corrupt governance are multiple and touch on all human rights. Empirically, it can be shown that countries with high rates of corruption (or high levels of corruption perception) are also the countries with a poor human rights record (Landman et al., 2007). According to Freedom House (2016) the human rights situation in the country has rapidly deteriorated in recent years. Sudan is ranked one of the nine countries judged to have the worst human rights record with its inhabitants suffering from intense repression.

Freedom of press

Several studies have shown a clear and strong negative correlation between freedom of the press and corruption (Ahrend, 2002; Brunetti and Weder, 2003; Freille et al., 2007). In Sudan restrictions on freedom of assembly and expression, freedom of the press, and equal access to the media have hampered a fair electoral contest (Transparency International, 2012). All of the above indicate an endemic corruption within the country. This causes citizens to face the tangible negative impacts of corruption on a daily basis and throughout all their activities.

The causes of corruption in Sudan

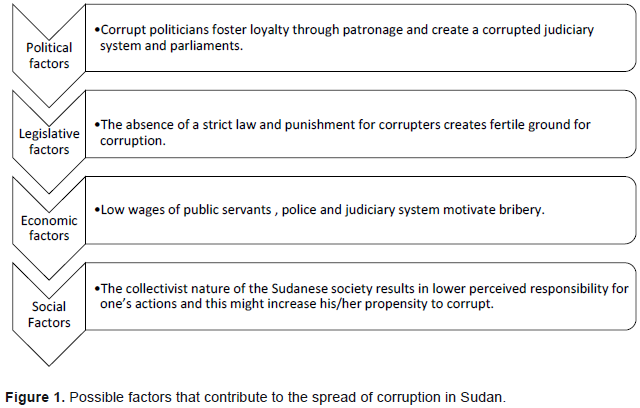

To be able to formulate effective policies to constrain corruption, it is important to identify the determinants of corruption (Jha and Panda, 2017). Generally, the determinants and causes of corruption are complex; they are made up of a combination of political, historical, social and cultural, as well as economic factors (Takács et al., 2011). This study analyzes the political, social, legislative and economic factors that may take a part in creating and increasing the level of corruption in Sudan. Figure 1 presents the study's model.

When the top leadership itself is a corrupter rather than a role model (political factors), and there is absence of an effective system for detecting corruption, and deterring criminals (legislative factors), in addition to low wages for public servants and the judiciary system (economic factors), this research suggests that every person could become a potential corrupter. Petty corruption will spread and flourish and, furthermore, will be tolerated. This research suggests that the reason why people might develop a high level of tolerance toward corruption is the collectivism of the Sudanese society (social factors). These factors are discussed and explained as follows.

Political factors: How corrupted government affects the society norms

As discussed above the absence of transparency within the top government triggers grand corruption. As a result, citizens' propensity to corrupt will increase since politicians—who are supposed to act in the public interest—are engaged in widespread and more serious corrupt activities. The public will change their estimate of the likelihood of being caught. This will influence the magnitude of dishonesty in which an individual chooses to engage. A person who is currently engaged in minor corrupt activities will be more likely to tolerate even more serious corrupt acts.

This is supported by the literature; Gächter and Schulz (2016) state that if politicians set bad examples by using fraudulent tactics like rigging elections, nepotism and embezzlement, then the honesty of citizens might suffer because corruption is fostered in wider parts of society. Citizens are less likely to abide by the law if they believe that others, particularly governmental leaders, are disobeying the law and avoiding detection and punishment (Spector, 2005).

The impact of a corrupt government could accelerate to the extent that it affects the society’s norms and values. Barr and Serra (2010) state that, all other things being equal, individuals who grow up in societies in which corruption is prevalent should be more likely to act corruptly than individuals who grow up in societies where corruption is rare. This is also concluded by Crittenden et al. (2009) who performed a worldwide survey of over 6,000 business students to study whether a link exists between corrupt countries and the attitudes of its people.

From what is seen above it is concluded that the spread of corruption within the top government leads to a greater tolerance towards corruption among the public.

Legislation factors: The absence of the rule of law

In Sudan, the absence of clear laws and regulations concerning corruption and corruptors boosts the spread of corruption in the country. The legal system represented by the judiciary is subject to high interference of the top government (Transparency International, 2012). In Sudan, corrupt officials are never caught. In the case that they are caught, they are rarely penalized and punished. According to Global Integrity (2006), only a few civil servants have been arrested and prosecuted for the embezzlement of public funds in Sudan.

According to the literature, if cheating is pervasive in society and often goes unpunished, then people might view dishonesty in certain everyday affairs as justifiable without jeopardizing their self-concept of being honest (Gächter and Schulz, 2016). Thus, the absence of law breeds more corruption.

Economic factors: Law pay cheque

What makes bribe widespread within the country of Sudan? Transparency International (2012) answers this question by stating that Sudanese civil servants, judiciary and police are poorly paid; thus, it is a common practice for them to extort bribes in order to supplement their low income.

The relationship between wages and corruption is debated in the literature. Theoretical studies by Ulhaque and Sahay (1996), among others, argue that higher government wages reduce corruption. For example, Tanzi (1994) states that unrealistically ‘low wages always invite corruption and at times lead society condone acts of corruption’. However, Rijckeghem and Weder (1997) mention that the magnitude of the effect of the government wage policy on corruption is controversial, and it is not certain that higher wages will lead to reduce corrupt acts.

Social factors: Collectivism, the mixed blessing

This section tries to answer the following question: does corruption—in addition to its political and economic factors—also have deeply rooted cultural causes and social traditions which largely determine its existence and extent? One of the prominent dimensions of a national culture is its degree of collectivism—in other words, the extent to which individuals in that culture see themselves as interdependent and part of a larger group or society (Hofstede, 1980; House et al., 2004). Sudan is a collectivist society that is too far away from being an individualist one.

Mazar and Aggarwal (2011) investigated whether collectivism can promote bribery. They conducted a correlational study with cross-national data and a laboratory experiment and found a significant effect of the degree of collectivism versus individualism present in a national culture on the propensity to offer bribes to international business. They suggest that collectivism promotes bribery through lowering the perceived responsibility for one’s actions. Their study is only relevant in the case of bribery, and cannot be generalized to all types of immoral behaviour or corrupt acts; however, it gives insights into understanding how a collectivist society works. According to Hui (1988) individuals in collectivist cultures, relative to those in individualist cultures, tend to hold more favourable attitudes toward sharing responsibilities. In addition, they perceive risky actions as less risky because they see their group or society as providing a ‘cushion’ that would protect them from harm (Hsee and Weber, 1999).

It is necessary to point out that collectivism itself is not a negative phenomenon and in its entirety does not promote unethical behaviour; however, it lowers the perceived responsibility for one’s actions which might assist in creating a greater tolerance towards corruption.

Why fight against corruption? The disastrous consequence

Not penalizing grand corruptors and forgoing and tolerating petty corruption in Sudan let corruption's level to move along an ever-increasing trajectory till it stifled all economic activity. Corruption impedes economic development and growth through different ways that are not limited to:

1. Corruption hinders investment (both domestic and foreign) and restricts trade. Private sector firms and foreign investors identify corruption as among the top constraints for doing business in Sudan (Gadkarim, 2011). Foreign investors will shun a country where corruption is spread. There is evidence that Sudan’s private sector faces major challenges to grow and diversify due to preferential treatment given to companies linked to the ruling elite (Transparency International, 2012). International Crisis Group (2011) highlighted how patronage exercises a negative impact on competition. Corruption distorts competition in public procurement procedures in the country.

2. Corruption results in inflation and inflation breeds more corruption. Al-Marhubi (2000) used cross-country data consisting of 41 countries and found a significant positive association between corruption and inflation, even after controlling for a variety of other determinants of the corruption. In addition, Akça et al. (2012) found that inflation had a statistically significant and positive effect on corruption in 97 countries that they examined.

3. One of the greatest obstacles to development is corruption in the public sector. Pritchett and Kaufmann (1998) state that how well the government spends its resources may be more important than how much it spends. In the case of Sudan spending on non-productive areas, such as the police and armed forces, leads to the underdevelopment in the country (Kameir and

Kursany, 1985).

4. Poor resource allocation also impedes economic development. It leads to a lack of allocation of entrepreneurial talents and the wasting of scarce resources, resulting in a failure to fulfil basic social needs. Murphy et al. (1991, 1993) mention that the primary losses of corruption come from the propping up of inefficient firms and the allocation of talent, technology and capital away from their socially most productive uses. Nepotism, on the other hand, leads to unemployment and less efficient workers. Cooray and Schneider (2016) state that corruption increases the emigration rate of high skilled workers from a

country.

5. As long as corruption is not controlled, the poor will stay poor. Corruption deteriorates countries' distribution of income (Li et al., 2000). It is suggested that corruption affects poor people more than wealthy ones, and this is proportional to the degree of its spread within a country.

6. Corruption deteriorates the quality of public infrastructure (

Tanzi and Davoodi, 1997) and reduces productivity (Lambsdorff, 2003). It addition it weakens the sense of loyalty toward civil and organized society, and causes low bureaucrat efficiency. It also results in cost enhancing by the rising cost of transactions through bribes.

7. Corruption affects society’s norms and breeds more corruption. Anand et al. (2004) mention that corrupt actions perpetuate continued corruption and, furthermore, that perpetrators do not view themselves as corrupt or unethical. When corruption is endemic within communities, it triggers a feeling of resignation and apathy.

Countries that stood up against corruption: The lessons learned

Although each country has its own unique political, social, economic and cultural components, it is believed that corruption problems in all parts of the world stem from common causes and may respond to similar approaches (Yeung, 2000). Thus, it might be of great help to study other countries' strategies in fighting corruption. This section presents and analyzes the experiences of some countries that succeeded in curbing corruption along with failure stories of other countries that could not succeed in reducing its level.

Lessons from success stories

Hong Kong and Singapore succeeded in fighting and reducing corruption. In both countries, to curb corruption an independent anti-corruption agency with widespread powers was established.

Fighting corruption: The Hong Kong experience

‘In the late 50s and 60s, corruption was pervasive in Hong Kong, in both public and private sectors. To the general public, corruption was an open secret and a recognized way of life. Syndicated corruption existed in law enforcement agencies and some government services were offered at a price. For example, in the Police Force, corruption was run as a business with large syndicates formed to collect “black money” systematically in return for covering vice operations. A bribe to Immigration officials could expedite an application for a visa or a passport. The installation of a telephone line could also be speeded up by offering a bribe to the staff of the franchised public utility company. Illegal commission in the business sector was commonplace. Then, the Government seemed powerless to do anything about it’ (Yeung, 2000, p. 2).

In Hong Kong the Independent Commission against Corruption (ICAC) was established in 1974 at a time when corruption was widespread, and Hong Kong was probably one of the most corrupt cities in the world. ICAC is a dedicated, independent and powerful agency to deal with corruption, with its commissioner directly responsible to the governor (Yeung, 2000). The ICAC created legal precedents such as ‘guilty until proven innocent’ (Klitgaard, 1988; UNDP, 1997). Hong Kong's ICAC adopts a three-pronged approach: punishment, education and prevention:

Punishment

Very restrictive new laws by the ICAC criminalized corruption by defining a lengthy list of offences that include the obstruction of justice, theft of government resources, blackmail, deception, bribery, making a false accusation, or conspiracy to commit an offence (Heilbrunn, 2004). Within three years, the ICAC smashed all corruption syndicates in the government and prosecuted 247 government officials, including 143 police officers (Man-wai, 2006). ICAC succeed because it was really strict in imposing the rule of law; no exceptions were made and no one was above the law.

Prevention

High salaries are offered to public sector officers to prevent them from asking for or accepting bribes (Heilbrunn, 2004). In addition, successful promotion of a code of conduct and declaration of conflict of interest guidelines have been adopted in all government departments and public sector organizations (Yeung, 2000). By doing so, ICAC succeeded in spreading awareness among civil servants.

Education

The education system starts to present children with ethical dilemmas and stories where the honest one always wins (Heilbrunn, 2004). The ICAC succeeded in changing the public’s attitude toward no longer tolerating corruption as a way of life and supporting the fight against corruption.

When ICAC was set up in 1974, very few people in Hong Kong believed that it would be successful. They called it ‘Mission Impossible’ (Man-wai, 2006). The public opinion survey in 1999 found 99% of the people surveyed had confidence in the effectiveness of the ICAC (Yeung, 2000). According to the latest Corruption Perceptions Index (2016), Hong Kong ranked as the 18th cleanest country in the world.

Hong Kong did not succeed in curbing corruption overnight. It took time and effort and above all resources. ICAC was financially well established and this helped in raising public civil servants’ salaries in a short period.

Fighting corruption: Singapore did it.

In Singapore during the British colonial period, corruption was widespread and perceived by the public as a way of life. Corrupt officials were rarely caught, and even if they were caught, they were not severely punished.

The Prevention of Corruption Act (POCA) and Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB) were born in 1960. CPIB came to the conclusion that the main causes of corruption were low wages and weak laws regarding corrupters' punishment (Quah, 2001). Singapore succeeded in fighting corruption through minimizing both incentives and opportunities to corrupt.

When the CPIB was established, Singapore was a poor country and the government was not able to afford raising civil servants' salaries. Therefore, it focused on strengthening the existing legislation to reduce the opportunities for corruption and to increase the penalty for corrupt behaviour (Quah, 2001). The raise in public servants’ wages began in 1972, and increased during the 1980s long after the country had achieved economic growth. Kim et al. (1993) state that the evidence of the CPIB’s success in reducing corruption is present from Singapore’s highly favourable investment. Hin (2011) states that political will was the key ingredient in fighting corruption in Singapore

Fighting corruption: Botswana has something to say

Among the states that have adopted Hong Kong's ICAC model, Botswana stands out. In September 1994, Botswana established the Directorate on Corruption and Economic Crimes (DCEC) (Republic of Botswana, 1994). Although Botswana's legislature lacks crucial elements of independence from the executive and is subservient to the president’s prerogatives, they somehow succeeded. This is due, but not limited, to:

1. The country has a highly developed bureaucratic state that governs without the controls imposed by a dynamic associational milieu or media (Molutsi and Holm, 1990)

2. Effective management of natural resource rents has brought the government substantial revenues that enabled it to overcome the budgetary impediment presented by anti-corruption commissions (Heilbrunn, 2004).

The DCEC, however, has no role in the prosecution of corruption cases; evidence is forwarded to judicial authorities. However, the numbers of cases actually forwarded for prosecution has been low, which probably reflects the sensitivities of Botswana’s government (Republic of Botswana, 2001).

Lessons from failure stories

Some of the reasons why some countries that imposed anti-corruption strategies failed in achieving their goals include but are not limited to the following.

Low level of political commitment

Thailand’s parliament established the National Counter Corruption Commission (NCCC) in the late 1970s to report any corruption cases. The legislature has been relatively weak due to the continued influence of cronies linked so closely to the regime (Rock, 2000). Tanzania is also a failure example due to a lack of commitment from the leadership.

The performance of Argentina, Nigeria, Brazil, Uganda, Bangladesh and India in fighting against corruption has been relatively poor. This is due to the absence of government will to stand against corruption (Heilbrunn, 2004). To conclude, reducing corruption needs a high level of commitment from the leadership.

Severe budgetary constraints

Establishing an anti-corruption commission needs money. Benin's Office for the Improvement of Morality in Public Life (CMVP) was faced with chronic budgetary shortfalls. The persistent financial crisis in the country made it unlikely that the CMVP could succeed (Heilbrunn, 2004). The success of Singapore-a country that was faced with budget constraints-suggests that it is not a matter of how much is available to accomplish the mission, but it is actually a matter of how well this will be spent to perform the task. Singapore overcame its financial disability by focusing on non-costly strategies to curb corruption. Eventually-despite the budget constraints-restricting the laws was quite successful in fighting corruption. Therefore, other countries, like Sudan, which are faced with budgetary constraints can follow Singapore’s strategy and need not be engaged in money-demanding strategies-at least at first. Eventually the cost of curbing corruption may be high, but the cost of not curbing it is much higher.

The size of the country

Hong Kong and Singapore each have substantial populations living in a small geographic area. Thus, an argument that the geographic size of the country determines the capacity to control venality has some credence (Heilbrunn, 2004). However, this is not a direct cause of success or failure, but it might be looked at as an aiding factor. Fighting corruption might be easier in small countries than in big ones due to the greater ability to control. Big states, like Sudan, should apply a strategy that helps to overcome the size constraints. Copying other small countries’ experiences might not be rational; however, adjusting these countries’ approaches to coping with the unique features of each country is more realistic. In the case of Sudan decentralizing the process among its states, this may be helpful in ensuring higher control capability. However, this will increase the need for external monitoring to ensure adequate application of the anti-corruption strategies. An analysis must be carried out to arrive at a suitable strategy to curb corruption in big states.

To conclude, any country that tends to fight corruption can learn from other countries' experiences in curbing corruption. However, each country has to bear in mind its unique and different features and statuses; thus, adjustments need to be carried out to consider a country's different circumstances.

War against corruption in Sudan: The remedies

Since the causes of corruption are interdependent political, social, economic, and legislative factors, successful implementation of any anti-corruption strategy should start by assessing and analysing these factors. Anti-corruption strategies should be comprehensive and holistic and take into account all possible causes and impacts of the problem under investigation.

This study suggests a holistic strategy that aims to minimize both incentives and opportunities to corrupt. Bearing in mind Sudan's current level of corruption and economic level, the strategy can be implemented in two phases that include a thorough diagnostic of the existing state of corruption in the country. Figure 2 exhibits the proposed strategy.

The first phase aims to discourage corruption by striking the laws regarding corruption and corruptors and apprising people about the endless negative impacts of corruption (spreading knowledge among citizens). This phase aims to change public perception of corruption from a low risk, high reward activity to a high-risk activity. On the other hand, the second phase aims to encourage anti-corruption, by buying out corruption in terms of increasing the public servants’ wages and competition between public service institutions. Second phase insures the paradigm shift in corruption perception into high risk, law reward activity. The coming sections present and explain the proposed strategy in details.

Commitment of the leadership

Institutionally, fighting corruption would require a commitment from the leadership (Ruzindana, 1997). This commitment is translated at the ground into:

-

Establishing an independent anticorruption agency.

-

Insuring transparency at all the country’s levels.

Establishing an independent anticorruption agency

The anti-corruption task should be assigned to an independent organization that has the right to investigate and arrest suspected people. The independence of the organization is not justifiable; and is the first step to guarantee the success of any anti-corruption plans. This is extremely and urgently needed in the case of Sudan; Transparency International (2012) mentions that in the country there is no anti-corruption agency at the federal level. In addition, according to Global Integrity (2013) in Sudan there is not an independent mandate to receive and investigate cases of alleged public sector corruption. Although the Auditor General Chamber’s independence is guaranteed by law, in practice it is subject to political interference and lacks the resources to fulfil its mandate.

The country’s public citizens are likely going to support any movement towards fighting corruption from the top leadership; according to the Transparency International Global Corruption Barometer survey (2016), 60% of surveyed Sudanese agreed that

ordinary people can do something against corruption.

Establishing such agency may be costly, especially for a surviving economy like Sudan. However, if the country shows any serious will to fight against corruption, it will get support from international co-operation from overseas anti-corruption agencies. In addition, unlike Hong Kong's ICAC, Singapore's CPIB was much smaller in size and did not need a large staff, yet it succeeded to accomplish its mission.

Insuring transparency at all the country’s levels

Ttransparency should be promoted and ensured to its greatest extent in all levels. Budget -including the military budget- should be disclosed. Also records of all expenditure including the presidential expenditure should be kept.

With a guaranteed commitment from the leaders first, all other anti-corruption approaches can be implemented as follow:

FIRST PHASE: Discourage corruption

The legislation approach: Increase the risk of corrupt acts

Since many studies (Pascual-Ezama et al., 2015)

concluded that individuals tend to cheat more in the absence of external monitoring, then tightening laws and legislations against corruption is essential to compact it. Usually a person tends to trade-off the benefits from corrupt behaviour against the penalties if caught and punished. For any person, it is worth the risk to corrupt as long as his/her expected losses (for example whether the punishment is imposed) are smaller than the profit from the privileges ensured by corruption (Takács et al., 2011).

Currently in Sudan corruption is perceived as a low-risk, high-reward activity. Thus, increasing its external cost (being caught/ punished) will decrease the intention to corrupt; in other words, when the penalty is greater than the intent then the intention to corrupt will decrease. This can be done through:

1. Enforcing strict laws and regulation, bolstering law enforcement, and prosecuting public officials/figures for corruption.

2. Eliminating the avoidability of punishment to its greatest extent. The success of this approach in fighting corruption is directly linked to the extent that no one is above the law and no exceptions are made. Bonga et al. (2015) stressed that to fight corruption the law should be enforced to its fullest and without fear and favour.

3. Establishing an effective corruption reporting system.

4. Some would argue that in Sudan the legal institutions who are supposed to bolster law enforcement are weak and often corrupt themselves. In such a case another strategy to fight corruption is delegation, or hiring integrity, from the private sector (Svensson, 2005), or the international community.

The education approach: spread knowledge

To a great extent people are not aware of corruption's extreme negative impact. Ordinary people tend not to think outside their everyday activities' zone. For example, they rarely make the link between corruption and the sudden increase in prices. That is why educating them and spreading knowledge is extremely helpful in changing their attitude towards corruption. They need to be educated about the social and the economic costs of corruption. This awareness will help in creating a disapproving behaviour towards corruption and will create a social anticorruption movement that is derived from the intrinsic values of the ordinary people who represent the society.

The channels where knowledge could be spread are not limited to:

1. Exhibitions, fairs, workshops as well as lectures provided in schools and universities.

2. Workshops and trainings for the civil servants in all institutions to spread valuing integrity and incorruptibility and priding values of service and excellence.

3. The use of media. In most countries, citizens receive the information they need through the media, which serve as the intermediaries to collect information and make it available to the public (Nogara, 2009). By drawing attention to acts that are generally perceived as acceptable ones and exposing corrupt ones, the media can raise public awareness, activate anti-corruption values, and generate outside pressure from the public against corruption (Rose-Ackerman, 1999). Mass media commercials, TV drama, press releases, media conferences and interviews can be used to share knowledge. Social media also plays a vital role in knowledge sharing. Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube have taken the world by storm. Short videos and messages can be transferred to billions through social media.

The media effect should not be underestimated; Uganda used newspapers and media to solve the problem of schools’ fund allocation. Only 13% of funds allocated for schools were reaching schools. To keep an eye on this, funds transfers to district education offices were published in newspapers and broadcast on the radio. In 3 years, the percentage jumped from 13 to 90% (Spector, 2005). Free, independent and hard-hitting media can play an important role in curbing corruption (Nogara, 2009).

Examples of messages for a clean society that can be prompted through the different channels explained above are not limited to:

Petty corruption is also corruption

In countries where corruption is widespread, people tend to tolerate it to a great extent compared to societies that are clean of corruption. The skewed perception of corruption needs to be straightened out and adjusted. Bribes, nepotism, the use of contacts and misuse of public resources need to be highlighted and explained as forms of corruption to the public

Stop tolerating petty corruption

People need to understand how they themselves are spreading corruption by tolerating it and not standing up against corruptors. An example of a knowledge-sharing campaign about the negative impacts of bribery can use messages like:

1-Bribery's negative impact on the economy is not calculated by how much each individual pays, but by how much we all pay as a people of a country. This is an extra cost that could have been employed more effectively in another productive activity.

2- Bribe askers should know that most of the gains go to bribers not to the bribe receiver.

3-Don’t tolerate bribery! You need not pay the bribe to get a public service—IT IS YOUR RIGHT TO GET IT! KNOW YOUR RIGHTS!

You are the only one responsible for your actions

As mentioned before, one of the reasons that might help indirectly in the spread of corruption in Sudan is the collectivist nature of the society which lowers the perceived responsibility for one’s actions. The spread of awareness and knowledge can be a way to increase each individual’s feeling of responsibility towards his/her own actions. People need to stop blaming society for what they are and for their own choices.

Know the laws, know your rights

Educate the public about their legal and civil rights and provide easy public access to information. This information enables citizens to challenge abuses by officials. In the long run when ensuring that people’s perception of corruption is changing, another policy that encourages people to report corruption and corruptors can be implemented. To arrive at this, first a society of people who never tolerate corruption needs to be built.

The impact of the education approach might be slow, but it is an important step in the right direction of transforming cultures of systemic corruption into societies that demand greater transparency, and strict enforcement of law and regulations.

SECOND PHASE: Encourage anti-corruption

Businessman approach: Buy out corruption.

This includes a wage improvement policy to decrease the incentive to corrupt and reduce the gap between the public and the private sector. Palmier (1985) and Banerjee (1996) identified low salaries as an important factor contributing to corruption. Aid donors and international organizations routinely recommend fighting corruption by paying higher wages to public servants. Historical examples of the success of this policy are Sweden and Hong Kong (Svensson, 2005).

This study agrees with Rijckeghem and Weder (1997) who suggest that while top government officials and legislators tend to maximize their gains through corrupt acts, civil servants may engage in ‘satisficing’ rather than ‘maximizing’ behaviour, and hence be only as corrupt as necessary to achieve a ‘fair’ income. This suggests that civil servants may willingly forego opportunities for corruption, if paid proper wages.

However, it should be clarified that the evidence on the relationship between pay and corruption is ambiguous. In cross-country studies, Rauch and Evans (2000) and Treisman (2000) find no robust evidence that higher wages deter corruption, while Rijckeghem and Weder (2001) find that it does.

1. Wage improvement policies to civil servants. However, the question is will Sudan be able to afford any extra payment to public servants, the police and judiciary? The answer is ambiguous. Bearing in mind the current economic situation of the country, the answer could be no, at least at present. On the other hand, it can be argued that due to the high level of corruption in the country, a great amount of Sudan's monetary and non-monetary resources are not employed effectively and efficiently. Therefore, if Sudan succeeds in curbing or even decreasing the level of corruption, then there would be resources available to fund a gradual increase in the public servants’ wages and salaries. Unlike Hong Kong, Singapore did not apply an increase in wages until the country maintained its economic health. This could also be the case for Sudan.

2. Paying the salary development policies as incentives for public service institutions that go forward in cleaning out corruption. This is simple and direct: the cleaner the institute is, the more incentives it gets. By doing so the budget constraints problem in the country is overcome.

3. The wage improvement policy has to be implemented in parallel with an effective corruption reporting system and effective monitoring and control of the public sector. The effectiveness of anti-corruption wage policies hinges on the existence of an honest third party that can monitor the agent (Svensson 2005; Takács et al., 2011).

Economic approach: Increasing the role of competition in the market

When officials dispense a government-produced good, such as a passport, the existence of a competing official to reapply to in case of being asked for a bribe will drive down the amount of corruption (Shleifer and Vishny, 1993). At least in theory, increased competition at the level of the official receiving the bribes may also reduce corruption (Rose-Ackerman, 1978). However, there is as yet no convincing empirical evidence that competition among officials actually reduces corruption (Svensson, 2005). The economic approach includes:

1. Increasing the competition of official offices that provide the same service. These offices could be monitors through official monitoring and unofficial one that is the word of mouth. Here, also, comes the role of the media through creating a social media pool in which people are sharing their experiences in public services institutions. This can become valuable information in monitoring and controlling corruption in public service institutions.

2. Motivate public servants incentives, in terms of the quality of the service that they offer, this will increase the competition and might result in reducing corruption.

3. Depending on e-government initiatives may help reduce corruption and increase accountability in the civil service.

Elbahnasawy (2014) presents evidence from cross-country regression studies that e-government strategies have helped reduce corruption in many countries.

To conclude the current study is a descriptive and a theoretical analysis of the issue of corruption in Sudan. It is one of the very few studies that considered Sudan as the case study. Unlike other theoretical studies of corruption, it is a comprehensive project that contributes to the literature by analyzing the problem of corruption from all possible aspects that are: its causes, diagnostics, consequences, and remedies. In addition the current study is also distinguishable as it suggests a holistic and a sustainable solution to corruption that are applied gradually starting from the short to the long run.

This research is of a great value to practitioners, it provides a guide on how corruption could be fought and how an anti -corruption strategy could be employed effectively. This research is a theoretical and a descriptive paper, thus further research is needed to examine some of the points stated in this paper empirically in general and specifically in the case of Sudan. For example, further empirical research is needed to examine whether corruption is contagious, and whether the collectivism of the Sudanese society contributes to the spread of corruption.

This research provided a holistic strategy to fight corruption. To insure the success of the strategy a full commitment from the leadership should be guaranteed. The strategy includes two phases; while the first phase tends to change the public’s perception of corruption from a low-risk high-return activity to a high-risk one, the second stage aims at making people view corruption as a low-return activity.

It is important to stress that, these strategies need time to start being effective and changes never take place overnight. Sudan—given its current level of corruption—needs ages to become a clean society. Second, it is everyone's responsibility within the country to stand up against corruption. Third, to ensure success, commitment from the leadership must be guaranteed. Fourth, it is a challenge and it’s a way that is not an easy task.

In conclusion, corruption is a social disease which is contagious. It is transmitted by direct or indirect interaction with an afflicted person. When the circle of corrupt people increases, the danger is even more serious. When a person is surrounded by corrupt people it is a matter of time for him to start feeling its effects on himself. People with a very strong immune system luckily may not get the disease, but others will definitely be affected by it—socially, economically, mentally, and even emotionally. That is why it is everyone's responsibility to stand for corruption, today before tomorrow, and now before then. In conclusion, fighting corruption is a not an easy task and changes don’t take place overnight.