ABSTRACT

Electoral campaigns are essential aspects of election. However, opposition political parties in Ethiopia have been challenged due to limited media alternative. In the 2015 general election, some political parties were using social media to conduct campaigns. Hence, this case study aimed to describe the status of these parties in the use of social media. The research utilized a qualitative approach as dominant method. Blue Party, Ethiopian Democratic Party (EDP), and Ethiopian People Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) were selected purposefully because they were active in social media use. In-depth interview, focus group discussions, and social media contents were used to collect data. The study used thematic analysis with a quantitative content analysis. The result revealed that political parties were introducing electoral symbols, policies, offline campaigns, and profiles of candidates through social media though there were discrepancies among them. The language predominantly used was Amharic that covers an average of 98% of the total messages. In terms of the mediums used, the study found that political parties were mainly releasing their messages through texts and a combination of texts and images. These two mediums cover an average of 77%. These imply the parties’ concomitance with the interest of the audiences. Generally, despite the use of social media to conduct campaigns is at its infant stage, the political parties dedication to use as well as their view on the potential of these media indicate that social media are becoming alternative channels of electoral campaigns in Ethiopia.

Key words: Social media, political parties, Ethiopia, 2015 general election, electoral campaigns,

Electoral campaigns are serious communicative advertise- ments undertaken by electoral candidates. According to Norris (2004) there are three main channels of communication to conduct campaigns:

1. The people-intensive channels such as demonstrations, public assemblies, party meetings etc.

2. The mainstream media which involves the print and broadcast media; and

3. The new media, mainly the social media (Arulchelvan, 2014).

Empirical studies conducted by writers such as Arulchelvan (2014), Williamson et al. (2010), Davies (2014), and Small (2007) have shown that political parties have been using social media to conduct their campaigns in this digital society, and found to have great potentials. In this regard, Davies (2014) has written that:

“Mainstream media, such as the press, television and radio, pay relatively little attention to most EU elections. However, the Internet and social media have become important alternative sources of campaign information”.

In similar way, Arulchelvan (2014) who has studied the experiences of Indian political parties has stated that “many political parties have created their own websites, blogs and Facebook/twitter accounts. They are enthusiastically using the tools for the election campaigns. This paradigm shift has significantly helped them in reaching the voters”. Such literatures are asserting that the social media are becoming one of the essential channels of electoral campaign.

In Ethiopia, a study conducted by Sileshie (2014) has asserted that the majority of Ethiopians have labeled Facebook as media, and “it is becoming relatively preferred media outlet (32.5 %) to television (21.5%), radio (17%) and newspapers (6.1%)”.

In addition, the coverage of internet is improving and the internet penetration rate is growing fast. According to the recent report of Internet World Stat (IWS) (2016), the internet penetration rate reaches 3.7% and the number of people surfing Facebook is equaled this number. On the other hand, the statistics released by Ethio-telecom (2016), indicates that the internet penetration rate reaches 12.5%, which tripled the estimation of IWS. Starting from the end of 1990s, the internet services mainly blogs were used by Ethiopians living outside to discuss various political issues (Megenta, 2010).

The existence of such literatures about promising potential of social media on the one hand and researcher’s observation of parties in Ethiopia using social media as channel of electoral campaigns on the other hand (Sinetsehay, 2015) have motivated him to explore the experiences in this regard. Given these motivations, this study aimed to explore the status on how political parties were using social media to conduct electoral campaigns.

Statement of the problem

In the past four round general elections held in the country, the people-intensive channels and the mainstream media were the only channels of electoral campaigns for both the incumbent and opposition parties. However, opposition political parties are always claiming that they lack enabling political space to conduct campaigns through people- intensive channels. People involved in these political activities have been exposed to frequent threats and political measures, which lead the people to abstain from such activities (Alemayehu, 2010).

The mainstream media are also in a critical problem. The state owned media (both the print and broadcast media) are remaining the mouthpiece of the government to portray propaganda (Teshome, 2009). During electoral campaigns, the incumbent took the lion-share of campaigning airtime and columns allocated (Alemayehu, 2010). Making the situation worse, private media have been becoming the target of frequent crackdowns, mainly after the 2005 general election (Ashenafi, 2013; Teshome, 2009).

In addition, the intimidation, harassment, and detention of journalists are becoming worse which leads journalists to self-censor their reports (Teshome, 2009).These situations make Ethiopia’s opposition political parties vulnerable in conducting their electoral campaigns effectively. With the aim of expanding their outreach, political parties used social media to conduct their campaigns in the fifth general election. Hence, conducting a research on their practice of using this option is essential, which is the heart of this study.

Although there are some studies on the issue by Tesfaye (2013) and Sileshie (2014), they have not addressed the situation of social media use by the legally registered political parties. They did not describe the condition on how political parties were using social media in campaigning. Hence, this study was conducted to fill the gap in relation to the status of political parties in using social media during the 2015 general election.

The general objective of this study was to explore the status of political parties’ social media usage in conducting electoral campaigns during the 2015 general election of Ethiopia. The specific objectives of the study are:

1. Describe the contents that were conveyed through the social media bases of the parties.

2. Investigate the language and medium preferences of the selected political parties.

3. Analyze whether these preferences were concomitant to the audiences’ interest or not.

Given the aforementioned objectives, the study intended to answer the following central questions:

1. What are the main contents that political parties were conveying through their social media bases?

2. What were the languages and mediums used by the selected political parties?

3. Were these linguistic and medium preferences concomitant to the interest of the audiences?

Scope of the study

This study aims to explore the practice of political parties in using social media as channel of electoral campaigns in Ethiopia by examining the experiences of selected political parties. Facebook and Twitter were the targets of the study from the different varieties of social media with a great emphasis to Facebook. The existence of relatively large number of Ethiopian online society surfing on these two social media types in comparison to other types of social media bases (Sinetsehay, 2015) has motivated the researcher to focus on these types of social media, mainly on Facebook.

In terms of the targeted group of the study, selected political parties contesting in the 2015 general election (Blue Party, EDP and EPRDF) were the central target of the study. Despite the critical problem of media space cited in the problem statement does not fit with it, the ruling party were also included in this group. The assumption of the researcher that this party will provide rich information concerning the issue given that it is an active social media user (Sinetsehay, 2015) is the rationality to include it. Methodologically, the study applied qualitative method backed by quantitative method for conducting this study.

In this era of the new media, the use of social media to conduct political communications is getting a great momentum. USA candidates were the first in using social media as channel of electoral campaigns (Williamson et al., 2010). Starting from then onwards, electoral contestants in countries such as Ireland, Germany, Austria, Sweden, Finland, Denmark, Poland and UK have used these media for conducting their electoral campaigns (Davies, 2014). Outside the USA and Europe, countries such as Canada (Small, 2007), India (Arulchelvan, 2014), and Malaysia (Gong, 2011) have used the social media for channeling campaigns. The experiences in such different countries are asserting the praised potential of social media as indicated by the stated writers.

In states where only the political elites have controlled over traditional mass media, an uncensored Internet can bring about social and political change in at least two overlapping ways. First, it acts as an alternative source of information, counteracting the agenda-setting function of government-controlled media. Second, it provides the basis for social mobilization and organization by providing avenues of interaction between content providers and consumers (Gong, 2011).

All these indicate how the social media are becoming an essential channel of political communications for political parties and other stakeholders who needs to bring political reformations. Small (2007) who has studied the experiences of Canadian political parties through a content analysis by taking the campaign messages of political parties posted for a month via parties web bases has found that political parties were using the internet in order to introduce their programs to the electorate.

According to the content analysis, Small (2007) has found that political parties did not narrowcast their policies to the various socio-economic groups. “The content analysis shows that, in general, Canadian party websites do not provide specialized campaign information for different regional or socio-demographic groups”. Small (2007) also has studied the interactivity of the Canadian political parties to their followers. The study found that the political parties have shown limited interactivity though one of the essential quality of the internet based campaigning is interactivity. Though there were quests to the different political parties campaigned through internet, “Canadian parties are failing to respond to voter requests for information” (Small, 2007).

Arulchelvan (2014) who investigated the experience of Indian political parties’ electoral campaigns through the new media have studied the nature of contents, colors of the text as well as mediums of campaign messages. The study found that political parties were mainly using the social media to campaign short mottos like “Vote for congress-DMK alliance, Vote for Corruption Free Government, to Fight against Price Rise and Terrorism Vote and Support and Elect BJP candidate” (Arulchelvan, 2014).

Emruli and Baca (2011) have investigated the internet and political communication of political parties in Macedonia. In their study, the content and the language version of political parties have been investigated by using content analysis. The language version in this study shows that, the political parties are mainly using their ethnic languages while few are bilinguals. “From analyzed Web sites , only 4 offer bilingual accessibility (30%), and others offer information only in the language of own ethnicity (unilingual content)” (Emruli and Baca, 2011).

In their study, the usage of foreign language, mainly English is covering 30% of the messages campaigned. A study conducted by Tesfaye (2013) on the challenges and prospects of online political communication in Ethiopia has found that English is predominantly used by the Ethiopian cyber society, and it is one of the challenges of non-English speakers of the country.

With regard to the mediums through which the messages were conveyed by political parties, the study conducted by Emruli and Baca (2011) is the one that have to be cited. By investigating the Macedonia political parties’ Web bases, they found that most of the contents were conveyed through texts.

The results of this part of the research shows that most of the websites of political parties are filled with textual contents, but the textual content is not linked to the outside source (Out Links) 31% of websites, while the multimedia content nearly 46% of the websites of political parties have no photo gallery, 77% of websites of political parties have no audio clips and 38%of websites have no video clips (Emruli and Baca, 2011).

Hence, as illustrated in the aforementioned related literatures, the investigations of contents, mediums and the linguistic preferences of electoral campaigners are common variables that ought to be investigated to describe how political parties are using social media to conduct their campaigns.

Regarding the theoretical framework, this study is mainly based on the Use and Gratifications theory. This theory assumes the audiences as active audience who can select the media and the content, which will satisfy their demands and hence the audiences have a control over the media (Ruggiero, 2000).

Hence, in order to analyze the concomitance of the audiences preferences on the contents, mediums and language usage of political parties, the use and gratification theory is used as a theoretical justification to the case from the side of the audiences (the activists in this case) while the political communication theory is considered as a theoretical justification for considering issues on the side of the senders (parties in this case).

The study used a concurrent embedded mixed research (qualitative as dominant and quantitative as supportive) approach with a case study research design. From the total of twenty three political parties contested at the national level (National Electoral Board of Ethiopia, 2015); three political parties (Blue Party, EDP, and EPRDF) were selected as cases of the study.

Given that the aim of this study is to render a on how the selected parties have been using the social media, a concern was given to the possibility of acquiring detailed information from parties that have better experiences. Hence, these political parties were selected by using intensity case selection method.

The researchers believe that intense and deep information can be collected from these parties because they were found to be the leading in terms of social media followers and involvement at these media (Sinetsehay, 2015). Moreover, they are leading political parties in other issues including the number of candidates they had and finance they received (National Electoral Board of Ethiopia, 2015).

The research considered participants from both the demand and supply sides. Considering both sides is essential to have a holistic understanding about the issue (Small, 2007). By using intensity purposive sampling again, two individuals from each party (supply side) were selected. Staffs that were running the social media bases of the parties as well as personnel who were heading the electoral campaign of the fifth general election in each party were chosen, and the data were collected through an in-depth interview with them. The data were collected on different days from January 18, 2016 to February 17, 2016. Each interview session consumed 45 to 65 min.

Activists of these political parties (demand side) were the other participants. They were selected through snowball sampling from activists in Addis Ababa. It is justifiable because the largest social media users are based in Addis Ababa (Freedom House, 2015) as well as many of the political parties are urban centered, and their political activities which bring exposures to activists are undertaken at Addis Ababa (Smith, 2007).

Members of the political parties who are relatively in better performance in demonstrations, party meetings and discussions, their contribution of membership fee as well as active involvement at the social media were identified through snowball sampling and a focus group discussion were undertaken with them.

A total of four focus group discussions (one in each party involving five to six members) were undertaken. Given the similarity of information collected from the participants of these different focus group discussions, the four focus group discussions were found to be sufficient. Each focus group discussion took about one and half to two hours.

In addition, the study used newspapers, government policies and statistics as well as contents of the parties’ social media bases to collect data. Because the contents were analyzed quantitatively, the research consulted the whole contents posted from February 22, 2015 to May 22, 2015 via the social media bases of the selected parties to avoid the problem of representativeness. Accordingly, 145 and 20 messages from Blue party, EPRDF and EDP respectively were analyzed. The researcher selected the period stated earlier because it was the official campaign period (Neamin, 2015).

After the data were collected in these manners, they were analyzed through a mix of thematic and content analysis. The data collected by interviews and focus group discussions were analyzed thematically. The social media contents were analyzed through a quantitative content analysis. The researcher undertook an inter-coder reliability test for contents taken from the social media bases of the selected political parties and the percentage agreement for inter-coder reliability test of this study is 87%. According to Krippendorff (), an inter-coder agreement is good if it is above 80% and acceptable if it lies between 67 to 79%.

Brief profiles of the selected parties

As cited earlier, the cases selected for this study are Blue Party, EDP, and EPRDF. Blue Party is a newly established political party, which came in to the political space after the 2010 general election. Despite the fact it is a recent founded political party, it is one of the firsts to be immerse into the social media (Sinetsehay, May 2015).

This party has a Facebook page named Semayawi Party-Ethiopia followed by 70,500 users. The party has also an online newspaper named Negere Ethiopia with a Facebook page followed by 44,000 users. According to the informants from the party, Ngere Ethiopia was formerly a print media. However, when publishers severed the challenges, this newspaper stopped its print publication and entered into online publication (interviewee 01, personal communication, April 28, 2016). The party has a Twitter page too named Semayawi Party followed by more than 800 users.

EPRDF was established in 1989 by ethnic based political parties. Despite the fact that the party is claimed to have unlimited presence via the mainstream media and people-intensive channels (Alemayehu, 2010; Teshome, 2009), it also avail itself at the social media bases starting from May 2014 as interviewees from the party have indicated. Now, EPRDF has followers of around 45,000 at its Facebook page named EPRDF-official and 6,000 at its Twitter account named EPRDF-Ethiopia.

EDP was established in 1992 and it is a member of Africa Liberal Network from Ethiopia as highlighted by interviewees from the party. Despite the fact that the party has relatively long history of involvement in Ethiopian politics; its presence at the social media is a recent phenomenon as EPRDF. It was in 2014 that its Facebook page Ethiopian Democratic Party was created (Sinetsehay, May 31, 2015). Currently, the page has about 13,600 followers, which is the third largest next to Blue Party and EPRDF in terms of followers.

The extent of use and the nature of contents conveyed

By creating social media bases as discussed so far, the selected political parties were using the media to conduct their campaigns along with an attempt to fulfill physical and human resources. In this regard, Interviewee 06 from EPRDF has said:

Our party is considering social media as one alternative channel of communication. Hence, we arranged the necessary personnel and physical equipment (office for the staffs, broadband internet service and computers) which were completed by the mid of May 2014. Then, we used the media to distribute our campaign messages.

After completing their preparation to use the social media, the political parties were inviting the online society to follow their campaigns at the social media at the beginning of the official campaigns (Figure 1). Regarding the extent of their parties’ utilization of social media, Participant 05 from EPRDF focus group discussants has stated the following:

Let alone the party itself, it also strived to motivate us to use social media extensively by setting agenda, attacking false propagandas raised by the cyber society, and to share various messages of the party including the campaign messages. During the campaign periods, the party was releasing campaign messages that intended to inform the party’s policies, electoral symbols (see also Figure 5) and previous accomplishments.

Figure 1 shows is the message of EPRDF at its Twitter page that called the audiences to follow campaign messages via the social media bases of the party in addition to campaigns conducted through radio, television, and newspapers.

Interviewee 01 from EDP has also informed that their parties were using social media to convey their campaign messages though they were not using these media to the extent that they have to use both in terms of interactivity and in terms of status updates. The reason behind their limited usage is the overloading of activities during the campaign period and the existence of limited manpower with such responsibility. Participant 03 from Blue Party focus group discussants has stated the following concerning the status of Blue party at the social media:

Our party was using the social media to releases various messages such as electoral symbol, press release, and somehow policies of the party and I was following these campaign messages at the social media bases of the party (see also Figure 2 and Figure 4). However, it was not answering the question that I forward through comments.

Figure 2 is an example of electoral campaign posted by EDP that attempts to explain its position to be a third alternative between the oppositions and the incumbent. With the aforementioned consecutive interviews, the idea of focus group discussant and the sample snapshot reflect that political parties were using social media to conduct their electoral campaigns. The political parties were attempting to take preparation in terms of physical equipment and personnel though there were limitations particularly in terms of interactivity.

Regarding the contents they released, the interviewees have reflected that they were releasing their policies and programs, electoral symbols as well as their offline campaign activities via their social media. Based on the deep review of the Facebook Page of the selected political parties, the largest messages were focusing on introducing policies and electoral symbols, which cover an average of about 72 % (65.1% by Blue Party, 80% by EDP, and 64.5% by EPRDF) from the total messages. Blue Party also spent at about 30% of its messages for exposing irregularities committed by the government and the incumbent EPRDF. EPRDF on the other hand, had released about 5% of its message that portray misconducts by opposition and 30% of its message were dedicated to different news. EDP spent the remaining 20% for different news.

As pointed by Interviewee 04 from Blue Party, Blue Party was additionally posting invitation to the offline activities (such as inviting to broadcast campaigns, rallies, and public meetings) and campaign messages rejected by the mainstream media. Moreover, it was posting profiles of candidates. Figure 3 shows the profile of candidates by describing their educational background, the seats they compete for, the district they represent, and the electoral symbol of the party along with the photo of the candidates. It was posted on the Facebook page of the party and also linked to its Twitter account.

Figure 4 portrays the political manifesto of EDP which is linked to its website as well as the party’s electoral symbol (flower as you can see) that is used to represent the party during the 2015 general election. As one of the purposes of electoral campaigns is creating an informed voter (Kriesi et al., 2009), the study found that the selected political parties were using the social media to create an awareness about their policies and electoral symbols, and Blue Party went further in creating awareness about its candidates (Figure 3). Political parties were also posting their offline campaigns to mobilize the online voters, which is in line to the mobilization purpose of campaigns.

As of the frequency of status update of these political parties is considered, the research found the existence of difference among the selected parties. Based on the review made on the Facebook pages of the selected political parties, Blue Party performed better with 221 status updates with an average of 2.5 status updates per a day while EPRDF –which is claimed to have many opportunities– has posted 145 status updates with an average of 1.6 status updates per a day.

EDP on the other hand, which has shortage of personnel to run the social media as pointed by the respective interviewees from the party has low (20) status updates when compared to Blue Party and EPRDF. This shows, though the parties try to update their posts; there were discrepancies in updating their messages.

Generally, from all the aforementioned data acquired through the various methods, it is possible to conclude that political parties were using the social media to channel their various messages such as electoral symbols, policies and programs, profiles of candidates, and offline campaign activities though there were discrepancies in their extent of use.

The language version

The other variable that this study has explored under the description of social media campaign is the language use of the political parties. Exploring the language version is important when one attempts to explore how political parties use the social media for campaigning (Arulchelvan, 2014; Emruli and Baca, 2011). It is essential to know to what extent political parties were performing in concomitant to the interest of the audience in terms of language.

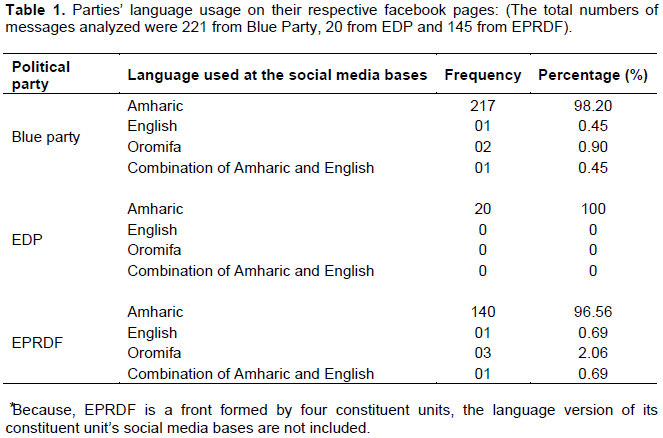

Accordingly, as of the language that parties used to convey their message via the social media, the content analysis revealed that 98% of the messages were released through Amharic language while the remaining 2% of the messages were released through English, Oromifa languages and combination of Amharic and English as illustrated in Table 1.

As, it is possible to understand from Table 1, the language dominantly used by the studied political parties is Amharic which covers 98.2, 100 and 96.56% for Blue party, EDP and EPRDF respectively. When, the average is calculated, 98% of the messages were found to be conveyed through Amharic language. The choice of Amharic language by the parties was found to be con- comitant to the interests of the activists of each political party though the activists also insist for the use of other local languages. In this regard, participant 02 from EDP focus group discussants has expressed his feeling as:

Because relatively large numbers of Ethiopians can communicate through Amharic, particularly when we come to the social media, it is important to use it. However, like that of the ethnic based political parties, it is also important for our party to campaign through the language of various groups as the party has done in the mainstream media. This is important to access the various linguistic groups as well as to attract their attention by showing that you are valuing their language as people are now highly attached to social cleavages such as language or ethnicity.

Interviewee 07 from EPRDF has stated that “our constituent members are using their local languages to reach their respective people on the social media while the EPRDF’s social media base was dominantly using Amharic language”. Political parties do have different experiences regarding the usage of other local languages. Despite the fact that there were linguistic narrowcasting by the constituent members of EPRDF, Blue Party and EDP were not found to have such narrowcasting.

Given that our party is not established based on ethnic arrangement, we did not have specifically campaigned message made to reach certain ethnic groups at the official level. However, our supporters at the individual level were taking the idea, interpreting to local languages and posting via their individual accounts. (Interviewee 03 from Blue Party)

Participant 04 from EPRDF focus group discussants has stated the following regarding the language usage of their party:

I am following the social media bases of EPRDF, mainly its Facebook page. The party is releasing the messages through Amharic language. It is very important to reach many people. I am also following the official Facebook page of Oromo People Democratic Organization (OPDO), which is one of the constituent units of EPRDF. This page is usually releasing messages through Oromifa language. Hence, members can access campaign or other messages by the language they prefer by following both pages.

These data reflect the necessity to campaign through different ethnic languages in order to narrowcast the specific ethnic groups though campaigning through Amharic is essential. Using Amharic language is supported because Amharic is communicated by the largest Ethiopian society (Cohen, 2008). However, as participants of different focus group discussions have pointed, the narrowcasting through different language is essential not only to reach voters that may not understand Amharic, but also to get the support of voters who are influenced by social cleavages such as language and ethnicity.

Medium of messages (Text, Video, Audio)

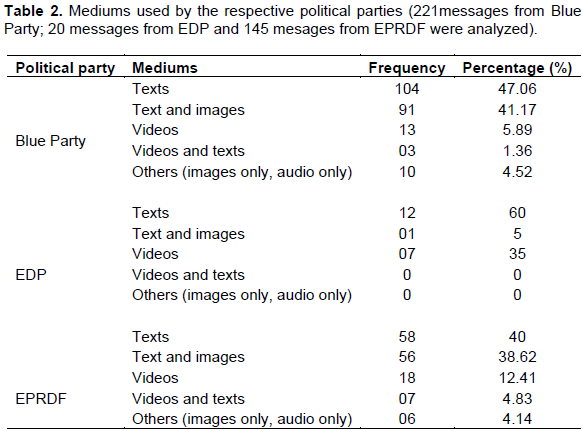

The other variable needs to be described while one illustrates how political parties use the social media or the internet at large is the type of the medium (text , video or else) through which the messages are conveyed (Arulchelvan, 2014; Emruli and Baca, 2011). Accordingly, based on the content analysis made for the various messages taken from the official social media basses of the selected political parties, the research found videos, images, text, a combination of text and images, and a combination of texts and video as the main mediums used by the studied political parties.

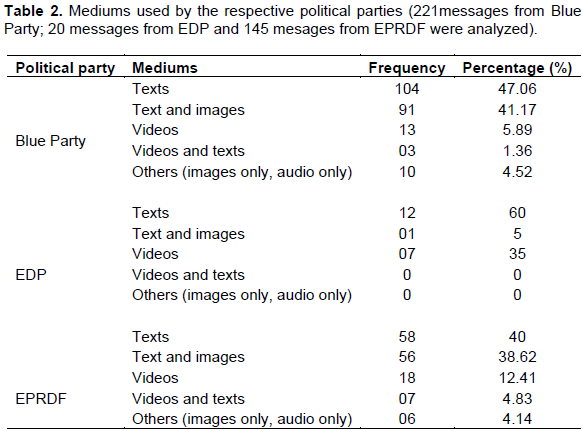

Table 2 shows the frequencies and percentages of mediums used by political parties to convey their messages via the social media. As it can be seen from the table, the selected political parties were mainly releasing texts and a combination of texts and image messages. The average text message of the three political parties is 49.02 %. The text and image messages also cover an average of 28.12%. This implies that textual oriented messages conveyed through texts as well as a combination of texts and images were dominantly used (covers 77%) to channel messages through the social media.

According to the data collected from the interviewees and focus group discussants, the choice of text and combination of text and images is not done haphazardly. Instead, the choice is justified for the reasons of slow internet connection and the relatively higher price needed to upload and download video messages. Despite one of the essential qualities of the social media is an impressive presentation by combining text, video, pictures and the like, these presentations are less likely viewed by the followers of a page as raised by informants.

Because the quality and cost of the internet are very challenging to upload and download videos, we were conveying our messages via text, and a combination of texts and images. Although we tried to release video messages, the likelihood of our audiences to view such message was low due to these challenges. (Interviewee 03 from Blue Party)

The claim of political parties for their choice of the medium is also supported by the focus group discussants. According to these participants, price and quality concerns have found to influence their choice of the contents. In this regard, participant 06 from EPRDF focus group discussants has said:

I usually depend on contents released through Text. Because it takes long time to download or view/listen video and audio messages; and it incur costs that cannot be afforded at individual level except I am moving to areas that have Wi-Fi connections, I have been rarely accessing video messages. Hence, I have been accessing messages released through textual oriented messages.

The idea proposed by EDP is slightly different in this regard, though still it uses text oriented messages by large, it has also posted video messages. Interview 01 from EDP has stated that:

We were using texts to release our messages for it is expensive to upload audio and video messages. However, we were sharing different videos related to our campaign messages and linked with the websites of the mainstream media such as Fana Broadcasting Corporate and Ethiopian Broadcasting Corporate.

Though, EDP was posting relatively many video messages (35% of the total messages on its page), the likelihood to be viewed by its followers is minimal as it was understood from the participants of focus group discussants selected from this party.

“Though there were some video messages, I didn’t open them since I am using a mobile data rather than Wi-Fi” (Participant 07 from EDP focused group discussants).

These entail how the medium preference of users is highly inclined to texts and combinations of texts and images than video messages due to the internet cost and the quality of internet connection. Generally, the data shows that political parties were using text-oriented messages than audio and video messages. As indicated earlier, the campaign messages released by text and a combination of text and images cover an average of 77% while video messages covers only 19.7%. Hence, it is possible to conclude that the studied political parties were performing in concomitant to the interest of the audiences in this regard because audiences rarely consume messages released through audio and video messages as presented so far.

In this section, the researcher discusses the major findings of the paper presented under the result section in relation to other related studies and theoretical views.

Extent of use and contents conveyed

The result of this study shows that political parties were using social media to conduct their electoral campaigns. The political parties were attempting to take preparation in terms of physical equipment and personnel. Regarding the extent of use as measured in terms of status updates, the study found that studied political parties were relatively updating their posts during the campaign period though there were discrepancies among them.

The existence of discrepancies in the use of social media is not unique to Ethiopian political parties however. For example, the study conducted on the 2009 parliamentary election of India has indicated the existence of discrepancies in the use of new media for campaigns among the studied political parties (Arulchelvan, 2014). Emruli and Baca (2011) have also shown the existence of differences among political parties of Macedonia in their use of social media both in terms of covering different campaign issues and in terms of releasing frequent status updates.

However, when their interactivity is viewed, the ideas taken from the focus group discussants assert that the selected political parties do have limited interactivity. The studied political parties were not able to respond to the queries of the users given both in the comment section and via the inbox chats. This is however, in contradiction to one of the main importance of the social media. As outlined by different scholars such as Davies (2014), Small (2007) and Ruggiero (2000), one of the main quality of the social media is to support interactivity. However, the interactivity of the selected political parties was found to be very limited though it is also manifested by the political parties of different states.

A study conducted by Small (2007) that investigate the experiences of Canadian political parties in the use of social media for campaigns also found that political parties do have limitations in terms of interactivity. “Canadian parties are failing to respond to voter requests for information which may be very problematic for a party, creating the perception that the party is unorganized, understaffed and inefficient” (Small, 2007). Emruli and Baca (2011) have shown that in terms of interaction, political parties are not handled and did not use the opportunities of new media field”.

Regarding the contents conveyed by the political parties through their social media bases, the result shows that the selected political parties were using the social media to create awareness about their policies and electoral symbols; and Blue Party went further in creating awareness about its candidates. As one of the objective of electoral campaigns is creating an informed voter by informing on policies and electoral symbols (Kriesi et al., 2009), the study indicate that the selected parties were using the social media for this end.

A research conducted in India indicated that political parties were using the social media to channel short messages and mottos such as “Vote for congress- DMK alliance, Vote for Corruption Free Government, to Fight against Price Rise and Terrorism Vote and Support and Elect BJP candidate” (Arulchelvan, 2014). This is in slight differences with the finding of this paper where the selected parties were found to inform about their policy alternatives. Moreover, introducing the photo, educational background, district and the house they compete for of the candidates is somehow unique which the researcher could not find in other studies being reviewed.

Moreover, the selected political parties were also posting their offline campaigns to mobilize the online voters, which is in line to the mobilization purpose of campaigns. Davies (2014) who has studied the experiences of different European states has stated that, “one of the main changes in campaigning with the advent of the Internet has been the use of social media's online capabilities to communicate and organize events that take place offline”.

Gong (2011) who has studied the experience of Malaysian political parties has also outlined that uncensored Internet enables opposition bloggers to garner support. “They have used blogs to distribute information not otherwise available, but to promote their political platforms and agendas, and to organize collective action, such as announcing rallies and other public events” (Gong, 2011).

The langue version

In terms of language, Almharic was found to be dominantly used by the selected political parties to convey messages, and it was found to be in concomitant to the interests of the activists with a claim for the use of additional local languages.

This finding is in contrast to previous findings. Tettey (2001) who has explored the internet and democratization process in Africa has found that the language used at the internet–English language–was posing a challenge to communicate easily because local languages were not in use.

Similarly, Tesfaye (2013) has indicated that English was the dominant language used at the social media bases in Ethiopia, which substantially excludes many of the society. Moreover, Megenta (2010) who has studied the effects of democratization in semi-authoritarian regimes by taking Ethiopia as a case found that it was English language which was chiefly used for the internet communication.

However, this study came up with a finding that entails the situation that political parties have campaigned largely through local language, Amharic. According to the data obtained from the interviewees and the focus group discussants, the emergence of equipment that supports local languages has contributed for this change. This essentially helps political parties to act in accordance of the language interest of the largest online society as raised by the focus group discussants.

The study also shows the necessity to campaign through other ethnic languages though campaigning through Amharic is essential. Campaigning through Amharic is supported because Amharic is communicated by the largest Ethiopian society (Cohen, 2008).

Nevertheless, as participants of different focus group discussions have pointed, the narrowcasting through different language is essential not only to reach voters that may not understand Amharic, but also to get the support of voters who are influenced by social cleavages such as language and ethnicity. A research also shows that ethnicity and language were the main determinant of voter’s behavior during the 2005 general election of Ethiopia (Arriola, 2007).

Given that audiences are active that select contents based on their interest as the uses and gratifications theory indicates (Ruggiero, 2000), the use of language by political parties was found to be one area of interest for the audiences that need attention by political parties. Nevertheless, the experience of the selected political parties to use other local languages is negligible, except EPRDF which is an ethnic based party.

EPRDF was found using local languages under the social media bases of its constituent units. The other, EDP and Blue Party, were not using the ethnic languages and unable to narrowcast to specific ethnic groups. This is however, in contradiction with one of the benefits of social media. Social media is essential to narrowcasting messages to certain specific group such as ethnic group (Small, 2007).

Mediums used to channel messages

The other objective was to identify the mediums that were used by the selected political parties in order to convey their messages via the social media. Accordingly, the result of this study shows that, the selected political parties were using texts, combination of texts and images, videos and combinations of videos and texts as the main mediums. Mainly, they were using textual oriented messages (texts as well as a combination of texts and images) to convey their message.

The utilization of video messages was minimal covering an average of 19.7% from the total messages of the selected parties released at their social media base. This is however, in contradiction with one of the essential qualities of social media. Social media are important to provide impressive presentations by combining different mediums such as audios, videos, texts, images (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010), the cost and quality of internet connection have been found to challenge the possibility of such impressive presentations both on the demand and supply side of the selected cases in this paper.

As the study shows, there are some video messages either out linked or posted by the parties themselves. However, the possibility of these messages to be viewed by the audiences is very limited as outlined by the focus group discussants. This claim is supported when the use and gratifications theory is considered. According to this theory, audiences who are active are selecting the mediums and the contents, which they think are compatible with their interests (Ruggiero, 2000).

Hence, though there are other mediums, the users are preferring textual and combination of text and image messages than videos and audios due to the quality and cost of internet connection. The study conducted on the Macedonian political parties also asserted that political parties have largely used textual contents than audios and videos (Emruli and Baca, 2011) though the context is different from Ethiopia. Similarly, Arulchelvan (2014) also found that textual messages with short and powerful words were applied to convey campaign messages by Indian political parties.

Based on the previous discussions and findings of the study, the researcher draws the conclusions as per the specific objectives of the study. The study was first tries to describe how political parties were using social media to conduct electoral campaigns.

Given the contention in the mainstream media and people-intensive channels, this research found that political parties were using social media to conduct their electoral campaigns and to undertake other forms of political communications. Political parties are being acquainted about the potential of the media and found to convey their electoral symbols, policies and offline campaigns activities via these channels in the fifth general elections to expand their outreach. However, the research found discrepancies in political parties’ extent of use. Accordingly, Blue Party was found to be relatively better in status updates and coverage of different campaign issues followed by EPRDF.

Unlike the previous conversations made on the social media which predominantly used English language, political parties were releasing their message through local languages mainly Amharic, which is communicable by the largest society. However, the study also found the demand to use other local languages to convey messages to attract the attention of diversified linguistic groups. In terms of contents too, political parties were releasing contents that are more likely to be accessed by their audiences in consi- deration to the cost and quality of internet services. These reflect the situation how political parties perform in line with the interest of the audience in this regard both in terms of linguistic and medium preferences. The situation is again an indicative of how the social media become important channel of communications for political parties in Ethiopia.

Generally, though the political parties’ involvement on the social is challenged by various problems, it is possible to conclude that social media become as alternative channel of electoral campaigns in the country given the problems in accessing other media alternatives. The political parties attempt to undertake preparation to use the media in the pre-election phase and their evaluation of the potential and their process in using these media in the post-election phase which imply the likelihood of social media to be relief for opposition political parties in Ethiopia.

1. It is important if the administrators of the social media bases of the respective parties can hold interactions by assigning the required personnel and by preparing campaign messages early: so that, they can get time to undertake interaction. It is also possible to take the questions of the majority and come up with a collective response.

2. For the sake of reaching large population, it is essential for the non-ethnic based political parties to undertake campaigns that are specifically able to reach certain linguistic groups as these media are suitable for such segmentations.

3. The poor quality of connection affects the opportunity of conveying messages by combining different mediums. Hence, meaningful efforts have to be made both to expand the connection well, and also to improve the quality of connection by the concerned organ.

4. Moreover, the price of internet is also found to be one of the challenges. Thus, it is essential to undertake a meaningful price discount to bring many users as well as to enjoy the impressive presentations that the social media supports.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Alemayehu GM (2010). Cartoon Democracy: Ethiopia's 2010 Election. Int. J. Ethiopian Stud. 5(2):27-51.

|

|

|

|

Arriola R (2007). The Ethiopian voter: An assessment of economic and ethnic influences with survey data. Int. J. Ethiopian Stud. 3(1):73-79.

|

|

|

|

Arulchelvan S (2014). New media communication strategies for electoral campaigns: Experiences of Indian political parties. Online J. Commun. Media Technol. 4(3):124-142.

|

|

|

|

Ashenafi A (2013). The framing of the 2005 Ethiopian national election by privately owned print media outlets in Ethiopia. MA Thesis. Mid Sweden University.

|

|

|

|

Cohen GP (2008). Mother tongue and other tongue in primary education: Can equity be achieved with the use of different languages? Davies R (2014). Social media in electoral campaigning. Euro. Parliamentary Res. Serv. pp. 1-8.

|

|

|

|

Emruli S, Baca M (2011). Internet and political communication – Macedonian case. Int. J. Comput. Sci. 3(1):154-163

|

|

|

|

Ethio-telecom (2016). ጋዜጣዊ መáŒáˆˆáŒ«:- ኢትዮ ቴሌኮሠበ2008 በጀት ዓመት የመጀመሪያዠመንáˆá‰… አበረታች á‹áŒ¤á‰µ አስመዘገበ(Press release: Ethio-telecom has brought a remarkable progress in the first half of the 2016 annual budget).

View

|

|

|

|

Freedom House (2015). Ethiopia: Country report on the net/2015.

|

|

|

|

Gong R (2011). Internet politics and state media control: Candidate weblogs in Malaysia. Sociol. Perspect. 54(3):307-328.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Internet World Stats (2016). Africa internet users, Facebook and population statistics.

View

|

|

|

|

Kaplan M, Haenlein M (2010). Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Kelley School of Business, Indian university. J. Bus. Horizons. 53:59-68.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kriesi H, Bernhard L, Hänggli R (2009). The politics of campaigning – dimensions of strategic action. In: Marcikowski, F. & Pfetsch, B. (Eds.), politik in der mediendemokratie pp. 345-366. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschafte publisher.

|

|

|

|

Megenta T (2010). The internet's democratization effect in authoritarianisms with adjectives: The case of Ethiopian participatory media. Oxford University.

|

|

|

|

National Electoral Board of Ethiopia (2015). NEBE is organizing data for future studies.

View

|

|

|

|

Neamin A (2015). Ethiopian political parties campaign for May poll. The Reporter.

|

|

|

|

Norris P (2004). The evolution of electoral campaigns: Eroding political engagement? John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University.

|

|

|

|

Ruggiero T (2000). Uses and gratifications theory in the 21st century. Mass Commun. Soc. 3(1):3-37.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Sileshie S (2014). Challenges and opportunities of Facebook as media platform in Ethiopia. J. Media Commun. Stud. 6(7):99-110.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Sinetsehay A (2015). Social media in fifth national electoral campaigns. Addis Fortune 16(787).

|

|

|

|

Small T (2007). Canadian cyber parties: Reflections on internet-based campaigning and party systems. Can. J. Polit. Sci. 40(3):639-657. Cambridge University Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Smith L (2007). Political violence and democratic uncertainty in Ethiopia [Special Report 192]. United States Institute of Peace.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Tesfaye A (2013). Social media as an alternative political forum in Ethiopia: The case of Facebook. MA Thesis. Addis Ababa University.

|

|

|

|

Teshome W (2009). Media and multi-party elections in Africa: the case of Ethiopia. Int. J. Human Sci. 6(1):94-122

|

|

|

|

Tettey W (2001). Information technology and democratic participation in Africa. J. Asian Afr. Stud. 36(1):133-153.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Williamson A, Miller L, Fallon F (2010). Behind the digital campaigns: An exploration of the use, impact and regulation of digital campaigning. Hansard Society, London.

|