Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

In Ghana, scholarly works on conflict financing, which sustains most conflicts is very much limited. Against this background, the Yendi chieftaincy conflict was purposely selected with the objective of examining the various resources invested in by the belligerents and other interested parties aside arms and ammunitions, which protracted the conflict and its resolution. A combined 59 respondents were purposely selected in a case study design. Primary data were gathered through interviews and focus group discussion. The study revealed that diverse resources invested in the Yendi chieftaincy conflict include; supply of arms and ammunitions, cash donation, funding of legal battles, and free supply of fuel and machetes. The paper recommends concerted efforts from stakeholders including the police, bankers, military, conflict resolution experts and fuel dealers to help deal with the menace of conflict financing which the study found to have contributed to the protraction of the Yendi chieftaincy conflict.

Key words: Conflict financing, protracted conflicts, chieftaincy, conflict escalation, Yendi.

INTRODUCTION

The African continent especially, has been plagued by all forms of conflicts - ethnic violence, chieftaincy conflicts, civic wars and inter-state conflicts among others. A number of lives and property have been consumed in these protracted and destructive conflicts. As noted by the UNDP Report (2005) (cited in Brown et al., 2007:2), about 40% of the world’s recent bloodiest and longest conflicts have occurred in Africa. Mention can be cited of Kenya (2007), Rwanda (1994) and Angola (1991-1994). These conflicts, as noted by Enu-kwesi and Tuffour (2010), are responsible for perpetrating misery and underdevelopment on the African continent.

According to United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECF, 2016), the Horn of Africa for instance, has been dominated and fragmented by intra and interstate conflicts. It noted that due to prolonged civil war, armed insurgency, coup d’état, revolution and rebellion incursions, government installations and administrative centers, roads and bridges, transport and communication facilities, schools and hospitals have been destroyed. It further reported that these conflicts have resulted in colossal human and economic costs and retarded the development of most economies in the region. Scarce resources from development are thereby transferred to support war. UNECF (2016) reported that an estimated 41,898 people lost their live in non-state conflicts between 1989 and 2014 in the Horn of Africa alone.

Unlike some West African countries such as Liberia and Sierra Leone which had witnessed varying degrees of civil wars and other forms of violent conflicts (Sirleaf, 2011), and more recently, Cote d'Ivoire and Burkina Faso, Ghana is overtly plagued by violent chieftaincy and ethnic conflicts (Kendie and Bukari, 2012; Hagan, 2006). Chieftaincy is a cherished heritage of Ghanaians (Brobbey, 2008), a traditional political institution where on the basis of native customs and laws, people with good morals are selected and installed as leaders (Nweke, 2012).

Yendi, the study locality has over the years witnessed violent chieftaincy conflict between two contending royal gates, the Abudus and the Andanis. Ahorsu and Gebe (2011) wrote that the disagreement relating to the rotational system involving the Nam Skin – the highest traditional political office of Dagbon – between the Andani and the Abudu predates Ghana’s independence. Awedoba (2009) noted that since the reign of Zangina as Ya Na in the 1700, succession to the Namskin (Ya Na status) has been revolved among the chiefs of Savelugu, Karaga and Mion (village gates). He further expressed that in the colonial times, the eldest son of the last king (Ya Na) - the Gbonlana, was roped into the contest for Ya Na in Yendi. Staniland (1975) however, maintained that since the death of Ya Na Yakubu 1 (1829-1849), the succession to the Yendi skin was rotated among his three sons Abdulai, Andani and Darimani in order (lineage gates).

He expressed that upon ascending to the Ya Na status, Darimani was deposed by the Germans only after seven weeks in succession to Andani. This according to Awedoba (2009) has since concretised the rotation system between the Abudu and Andani lineage gates.

Owusu-Ansah and McFarland (1995) documented that the rotation system witnessed a new twist in 1954 when Mahama Bla III (Ya Na) from the Abudu gate was succeeded by his son Abdulai III from the same line of royal family.

The contention between the two antagonistic gates assumed a violent tone in 1969 and led to the death of 23 people from the Andani family (Mahama, 2003). The re-current violent clashes between the two feuding royal gates in 2002 resulted in the death of Ya Na Yakubu Andani II, the overlord of Dagbon and 28 others in Yendi (Wuaku Commission Report, 2002). This according to the report triggered a mass exodus of residents of Yendi to safe locations, particularly Tamale and its environs and nearly led to a breakdown of law in Yendi and the entire Northern Ghana. The implication was that, the Dagbon state with Yendi as its traditional political seat (capital) was without a substantive overlord (Ya Na) from March, 2002 to January, 2019.

The Yendi case among other inter and intra-ethnic conflicts in Ghana could be considered as a small-scale and low intensity conflict given the parties involved. Ibrahim (2018) labels this conflict as an internal family dilemma over ascendancy to the Yendi Skin (throne). Nonetheless, Awedoba (2009) expressed that the conflict has been described as the worst dynastic conflict since Ghana’s independence. The King was killed, dismembered and parts of his body used as trophies of victory, an affront to the cultural heritage of the people and the chieftaincy institution as a whole. The Yendi conflict apparently, became a drum in Ghana, which was beaten by politicians and other individuals with varying interests and orientations. An understanding of the dynamics of this particular conflict was thus critical.

Various attempts to resolve the Yendi chieftaincy conflict have led to the institution of a number of Commissions notably, the Azzu Mate Kole Commission of 1968; Ollenu Commission of 1974 and Wuaku Commission of 2002. The conflict has also seen the promulgation of Legislative Instruments (L.I) including; L.I 59 of 1960; L.I. 596 of 1967 and the National Liberation Council (N.L.C) Decree 296 of 1968 (Wuaku Commission Report, C.I.36, 2002; Awedoba, 2009; Tonah, 2012). Besides, the courts, the police and the military had featured prominently in the Yendi conflict. Seemingly, the findings and efforts of these committees and bodies largely could not successfully resolve the conflict. The conflict, from all indications, assumed a protracted and destructive dimension and was only resolved in December, 2018 which paved way for the installation of a new Ya Na in January, 2019.

The question which this study seeks to unravel is, ‘Why in spite of the numerous deliberate attempts to resolve the Yendi chieftaincy conflict at various levels as found in extant literature, the conflict protracted and exacerbated until January, 2019, when a new king was installed? Could this be attributed to the issue of conflict financing? The fact is that there are plethora of information on the various interventions to the Yendi chieftaincy conflict and its overall destructive nature (Awedoba, 2009; Mahama, 2003; Wuaku Commission, 2002). However, scholarly works done on the issue of conflict financing - the act of spending various resources on conflicts which invariably protracts and exacerbates most destructive (low intensity intra-ethnic) conflicts in most of the conflict zones as espoused by Rose (2018), has not received as much attention as it deserves in the Ghanaian setting. This is the niche of the study. There is the need to probe the Yendi situation beyond the obvious drivers of protracted conflicts such as natural resources and small arms.

As noted by Wennmann (2007), the use of natural resources in financing some conflicts is unquestionable. He however, argues that in other conflicts, they are of minor importance. Annan (2010) has emphasized on how small arms sustain and exacerbate armed conflicts. He noted that small arms endanger the lives of peacekeepers and workers, undermine respect for international humanitarian laws, threaten legitimate but weak governments, and benefit terrorists as well as the propagators of organized crime. What these discussions suggest is that the modes of conflict financing are not limited to only natural resources and small arms. This calls for a critical probing into those silent drivers which nonetheless sustain conflicts and complicate their resolution. With this understanding, it is envisaged that stakeholders, including; the government, the chieftaincy institution, Non-Governmental Organizations, the security services and the general public who are concerned with the sustenance of peace and development of communities would be well-informed about the broad factors that sustain conflicts. Armed with this information, they would be in a better position to take keen interest in working jointly with the view to galvanizing all efforts and resources to improve and sustain the peace and development of communities which often are derailed by destructive and protracted conflicts. As noted by International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC, 2016), in most countries, complex infrastructure which support communities such as electricity systems, schools and hospitals, have either been destroyed or damaged due to protracted conflicts.

Conflict financing and conflict dynamics

The growth, sustained and destructive nature of conflicts make it necessary to look deeply at the likelihood factors responsible for such escalation. ICRC (2016) has expressed that the length, difficulty and complexity characterising protracted conflicts are not new. What is new according to ICRC (2016) is their ever changing and increasingly complicated nature. ICRS (2016) noted protracted conflicts disrupt the functioning of societies and undermine various support systems crucial to the lives of the people. ICRC concluded that prolonged wars have debilitating effects on societal gains in terms of progress and development.

Rose (2018) in her view expressed that there is evidence of the link between organized crime and terrorism financing in most escalated conflicts across the African continent. This state of affairs, as noted by Rose (2018), has created a stereotype of Africa as a doomed continent with inescapable violent conflicts. The sources of financing of conflict are diverse and often vary with the agenda and operations of the combatants and the conflict entrepreneurs.

Rose (2018) study found that Boko Haram and Al-Shabaab terrorists groups for instance, have been able to sustain their operations due to financial resources as manifested in Nigeria and Kenya respectively. Earlier, Addison et al. (2001) had hinted that conflicts, and for that matter wars, are sustained through remittances from Diasporas. These authorities noted that Kosovar Albanian resistance was sustained as a result of financial support from Kosovar Albanians working in Germany.

They further contend that the operation of the Tamil Tigers in Sri Lanka became persistent due to remittances.

Wennmann (2007) wrote that armed groups and combatants use various forms of financing methods to sustain their military activities including; bank robbery, foreign government support, revenue from natural resources, kidnapping, diaspora remittances, and taxes. Wennmann (2011) study reveals that the context of conflict zones defines the form of an investment that may be required. His study found that in Nigeria, the presence of oil defines incentives for oil theft, kidnapping of oil workers, and support from frustrated communities. Contrarily, as his study revealed, the political nature of the Israel/Palestine conflict invites often contested foreign government support; while armed groups in Indonesia, Somalia, and Sri Lanka draw on diaspora remittances and taxation of local communities. In furtherance, his study found that in Kosovo, the conflict was financed by Kosovo Albanian Diasporas typically in Switzerland or Germany. He concluded that transfers of money into Kosovo occurred mainly through cash couriers, whilst money was wired to accounts in Albania.

Wring on the Rwanda genocide, Jones (2011), Verwimp (2006), McNulty (2000) and Gourevitch (1998) studies found that the Tutsis ethnic group were systematically killed by the Interahamwe militias and the Hutus with the use of machete - a familiar agricultural tool. They indicated that boxes of machetes were even imported from countries such as Belgium and China. In their view, the machete is a very popular implement in the third world and as such, has played a pivotal role in many uprisings and rebellions especially in Africa.

Horowitz (2000) wrote that labour migration and flight to escape civil war or repression have increased ethnic heterogeneity both within and across states. He noted that these inter-ethnic group formation and interethnic relations (networks or diaspora associations) have often served as sources of mobilizing funds in fueling homeland conflict or promoting peacebuilding. He cited Sri Lanka, Angola and Kashmir as countries where diaspora relations have helped in fueling violence. Baser and Swain (2008) study equally found that the Kurdish diaspora in Europe substantially contributed to the intractable conflicts in the homeland by providing financial support to the rebel groups. Their study revealed that the Kurdish diaspora raised large sums of money in Europe to financially support the violent activities in Turkey and most of these contributions appear to be voluntary.

Kaldor (2001) and Duffield (2002), advocates of ‘New Wars Theory’ have equally argued that migrants or Diasporas bear a strong influence on conflict in post-Cold War era. They wrote that warring parties have maintained strong ties with their original homelands through several cross-border networks including the use of modern communication technology such as; WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube as evidenced in the recent so-called “prodemocracy” revolutions in the Arab world even in the face of severe crackdown on traditional media. This according to them has made it easier for the illegal transfer of arms, drugs and other technology from the diaspora to the home country in aid of their sympathisers for the continuation, if not the reinforcement of violence. This shows the close ties between migrant communities and their homeland.

Writing about the protracted conflict cycle and insecurity in eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, Kinyua (2017) expresses that the supply of arms and cash by the state, transnational companies and intergovernmental organizations to the combatants has played a role in escalating the conflict so as to reap the benefits of unregulated mineral trade. His study concluded that the occasional escalation of the conflict is increasingly dominated by economic interests rather than political motivations.

The preceding arguments and the information they presented are very helpful. They stimulate the interest and the need for interrogating the broader forms of conflict financing or investments beyond what is generally perceived to be the obvious that sustain the operation of combatants in these destructive conflicts which often escape the knowledge of academics and policymakers. This underlines the motivation for adopting Hirsch’s (1977) Theory of Scarcity of Positional Goods (cited in Mitchell (1981:19-21) in the study.

The Theory postulates that in more multifaceted societies, conflicts arise over competition over scarcity of material and positional goods construed as valuable. Thus, issues surrounding the occupancy of a particular scarce position or decision-making roles for society, or the exclusion of particular others from scarce positions of influence such as political office become the basis of contention. The Theory indicates that success in conflicts over limited position creates a widening gap between the contending parties which results in the development of a fragmented social structure of ‘have’ and ‘half-not’ (or half-less) groups as parties pursue goal incompatibilities. Mitchell (1981) intimates such social arrangement manifests in fierce competition and violent conflicts as witnessed in Nigeria, Vietnam, Cyprus and Lebanon.

The Yendi protracted chieftaincy conflict fits into the Theory of Scarcity of Positional Goods. As indicated by Awedoba (2009), the chieftaincy conflict in Yendi involves a competition between two royal gates over a traditional political position - the chiefship. In applying the Theory, this paper assumes that the feuding gates and their sympathisers in the Yendi chieftaincy conflict are rational players competing for economic and political power (rewards) that will entitle any member of the group or network to social, economic and political rights. As noted by Hagan (2006), competition among legitimate royals in Ghana has become so intense that royals are divided and are prepared to use arms to settle the issue of who occupies the stool/skin. Parties therefore invest various resources in the conflicts with the view to win irrespective of the costs involved. As a result, communities are riven with permanent and intractable chieftaincy succession conflicts (Hagan, 2006). Belligerents, sympathisers and or conflict financiers thus, have various reasons of financing conflicts. This makes the Yendi chieftaincy conflict an instrumental one, in that the main question of investing in the conflict arises from a realistic pursuit of objectives.

Awedoba (2009), has pointed out that the title of chieftaincy attracts both material benefits and prestige within the community and without, and remain a limited good that is keenly sought after. Buttressing the point, Awedoba (2009) cited the Kusasi-Mamprusi inter-ethnic conflicts in Bawku, as an example. He expressed that the contention between these two ethnic groups is grounded in chiefship and that such a conflict has implication for land ownership in the metropolitan area which continues to grow and where landed property commands considerable prices. In Ghana, claims to land (Hagan, 2006) and or title or ‘positional good’ as earlier espoused by Mitchell (1981), have been cited as among the principal motivating factors which push combatants and conflict financiers into chieftaincy conflicts which invariably protract these conflicts and their resolution.

The emerging idea is that combatants and financiers find innovative ways of financing conflict so as to avoid the end of an armed group. As noted by Wennmann (2011), conflict financing is inherently dynamic, not static and as such, strategies are quickly adapted in the face of threats or to explore new opportunities as they arise. Given this dynamic situation, any pragmatic approach to a protracted conflict situation as in the case of the study locality, may require actors with different skills.

METHODOLOGY

Study locality

Traditionally, Yendi is the capital of the Dagbon Kingdom and it is predominantly inhabited by Dagombas. Yendi is equally the administrative capital of Yendi Municipality. The population of Yendi Municipality, according to the 2010 Population and Housing Census (Ghana Statistical Service (GSS), 2012) stood at 117, 780. The predominant religion in the Yendi Municipality is Islam, with more than two thirds of the population professing the Islamic faith. Traditionalists account for 13.2% whilst Christianity constitutes 7.2% (GSS, 2012). Seemingly, major conflicts in the area over the years have not been fought on the basis of religion. This could suggest that there is some level of religious tolerance in the locality.

A greater majority of 65.4% of the population engages in agricultural production (GSS, 2012). What the figure suggests is that any social hazard like deadly conflict which affects the environment (land) is likely to undermine the livelihood of the people (Marfo et al., 2019). As asserted by Simmons (2013), destructive conflicts damage the livelihoods of the millions of poor households whose source of income depends much on agricultural production. In view of this, matters relating to land conflicts need to be given the necessary attention.

Apparently, due to violent and protracted chieftaincy conflicts, Yendi locality over the years has not seen any meaningful peace.

Research design and selection of research participants

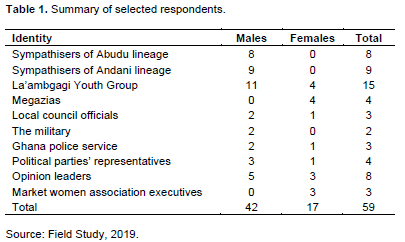

This paper employed the case study design. This design was chosen in view of the fact that there was the need to learn in detail as much as possible from the respondents own perspective. The study targeted sympathisers of the two feuding descent groups, opinion leaders, local council and political party officials and youth group members in the study locality. The researchers operated with a combined 59 participants. All the eight key informants namely; representatives of Market Women Association Executives, Ghana Police Service and the Military were purposely selected. Likewise, 34 other respondents besides the 17 sympathisers of the Abudu and Andani descent were selected purposely. The 17 sympathisers of the Abudu and Andani descent were selected using convenient sampling technique with special selection criteria. This was done in order to reach a fair number of both Abudus and Andanis sympathisers so as to get a broader view of the conflict.

From the responses given during the data collection phase, the researchers noticed that selection saturation was reached as the respondents gave virtually similar responses. The implication was that the views of any other selected respondents would have added no new insights to the information gathered. Given the sensitive nature of the study and for the purposes of neutrality, the researchers intentionally did not engage any of the immediate royal family members or spokes persons of the two feuding royal families including the seated Ya Na (the over lord) (Table I).

Data collection methods and analysis

Primary data were gathered through interviews with the aid of interview guide and focus group discussion facilitated by a discussion guide. Forty-two (42) separate face to face interviewing sessions were held at different times for the selected respondents excluding the La’ambgagi Youth Group each lasting averagely 35 min. Issues discussed centered primarily on the seemingly unnoticed resources invested in the Yendi chieftaincy conflict which nonetheless stretched the conflict and its resolution. On the other hand, an extended focus group discussion was held with the La’ambgagi Youth Group (15 discussants). The focus group discussion was intended to seek the diverse views of the youth on the resources as spent on the Yendi conflict. This was critical because as noted by Urdal (2012) and Goldstone (2018), the youth, especially the young males, are often the main protagonists of criminal and (political) violence. In this regard, by including their perspectives on the various forms of investment spent on the conflict, it was expected that new concepts and ideas for inclusive peacebuilding process could be obtained. The researchers sought the help of a field assistant who assisted in transcribing the data. In addition, previous works that provide the required information on the subject matter were reviewed to complement the primary data. The researchers employed qualitative approach to examine the issues at stake. Qualitative analysis was undertaken to generate a descriptive picture of the data gathered. Data from interviews and focus group discussion conducted with all the respondents were transcribed and analysed manually by making summaries of their views and categorized into themes. On ethical grounds and for the purposes of anonymity and confidentiality, the names of the respondents and their characteristics were not disclosed in this study.

RESULTS

Biographic data

This section contains the biographic information of the respondents. It covers the age distribution, educational qualifications and sex composition of the respondents. It was necessary on the part of the researchers to consider these characteristics of the respondents as they tend to influence understanding, analysis and decisions pertaining to chieftaincy conflicts and their resolution as witnessed among the people of Dagbon.

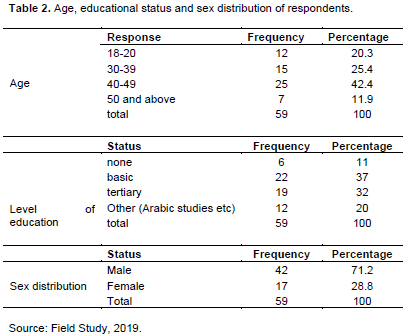

Age, educational status and sex distribution of respondents

The respondents were asked to indicate their ages. This was in line with the aim of targeting a segment of the population who were 18 years and above.

The age distribution across the various age brackets was an indication that the views of all categories of the respondents from 18 years and above were represented. This could give a true picture about the problem at stake. In terms of educational qualification, the study found that the respondents were made up of persons with secular and other Arabic and traditional studies. There were persons with secular education from basic to the university level, while others had Arabic knowledge. Aside, some respondents had no formal education. The results indicate that majority of the respondents (50) had attained some level of education. The results also showed that 42 respondents were males as against 17 females. The skewed nature of the respondents in favour of males stemmed from the fact that the chieftaincy institution with its embedded conflicts is dominated by males (Odotei, 2006). The results however, demonstrated that the views of both males and females were fairly represented. This is very important in that males and females have different roles and interpretations of conflict. The biographic information as gathered is captured by Table 2.

Resources spent on the Yendi chieftaincy conflict

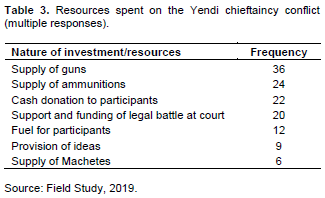

The thrust of the study was to interrogate the various forms of resources which served as fodder to protract the Yendi chieftaincy conflict and its resolution. This was necessary because as indicated by Rose (2018), sources of financing of conflict come in many forms. In response to the question as to whether people have been financing the Yendi chieftaincy conflict, 38 respondents answered in the positive while 13 said they had no idea. All the eight key informants also shared similar view that the Yendi conflict has witnessed various forms of investment.

In furtherance as to the resources invested in the Yendi conflict by the people, seven responses were given as captured in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

The analysis revealed that majority of the respondents (38/51) opined that various resources were invested in the conflicts. Buttressing the point, this is what a respondent (R2) exclaimed:

‘For the Yendi chieftaincy conflict, a lot of people invested their resources in it. Big men, politicians and the youth used to contribute weekly and sometimes monthly to finance the conflict. You would be surprised to know the people involved including women’ (A Respondent Remark, 2019).

The views of the people were in accordance with that of the key informants. This is what was expressed by K3:

‘People and even organisations spent their resources on the chieftaincy conflict for their selfish gains’ (A key Informant Interviewed, 2019).

The information gathered is an indication that conflict financiers or entrepreneurs may come from different socio-cultural, economic and political backgrounds.

The emerging idea is that people - both males and females and organisations from within and outside the immediate conflict environment were implicated in the financing of the conflict. The information gathered also suggests that both internal and external resource mobilization schemes contributed to sustain the conflict. This finding is in line with Addison et al. (2001) study which found that Diasporas remittances, commercial and official borrowing have been forms of external capital inflows that are used to finance conflicts.

The assertion that politicians are involved in the financing of the Yendi conflict is a manifestation that chieftaincy conflicts, as in Ghana, have assumed a political dimension. This revelation validates Abokyi’s (2018) study which revealed that partisan and political undertones have served as forage to aggravate chieftaincy succession conflicts, land and boundary disputes in Northern Region of Ghana. He intimated that Northern Region has over the years been a hotbed of conflicts as several communities have gained notoriety for frequent violent disturbances. His study implicated the two giant political parties in Ghana; the National Democratic Congress (NDC) and New Patriotic Party (NPP) in the Yendi chieftaincy conflict, citing that the Andani royal family tend to support the NDC whilst the Abudus are usually on the side of the NPP.

Abokyi (2018) concluded that individual government officials show a natural inclination towards their own ethnic groups, as has been seen in Bawku and Yendi chieftaincy conflicts. The policy implication is that, an inclusive approach involving critical stakeholders has to be taken in attempt to transform the chieftaincy institution in Ghana.

Supply of guns and ammunitions

Small arms are known to be a major driver which sustains and exacerbates armed conflicts (Annan, 2010). In the case of the study locality, the situation was not different. Thirty-six (36) respondents indicated that the supply of guns was a major resource spent on the Yendi chieftaincy conflict. This is what a respondent (R4) said:

‘I was surprised to see the kind of arms people from the two factions were using during the conflict in 2002 and wonder how they came by those arms. I was told their financiers usually supplied them’ (A Respondent Remark, 2019).

The views of the key informants were in line with that of the respondents. A key informant (K1) remarked:

‘We cannot deny the fact that the guns used by the ordinary civilians were supplied by external parties. Let us be frank with this. None of the combatants will use their monies to buy such expensive guns. These guns were usually purchased by the financiers of the conflict’ (A key Informant Interview, 2019).

From R4 and K1 assertions, it could be suggested that the respondents have a fair idea as to how the combatants were able to secure sophisticated guns from people outside the immediate conflict environment (Diasporas relations/financiers) to wage and sustain the conflict. The information gathered from the respondents was in line with the findings of the Wuaku Commission Report (2002). According to the Report, ‘G3’ – a German made gun which is used in Ghana basically by the military was retrieved from the Gbewaa Palace after the clashes between the two protagonist groups in 2002. Though the Report could not identify the source of the gun, the manifestation is that modern (imported) weapons were sneaked into the conflict zone by sympathisers/financiers which played a major role in the protraction of the conflict. Kaldor (2001) and Duffield (2002) in their respective studies earlier found that through the use of modern communication technology such as; WhatsApp, Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube, warring parties in the Arab world have been able to maintain strong ties with migrants or Diasporas. According to these authorities this has facilitated the illegal transfer of arms, drugs and other technology from the diaspora to the home country in aid of their sympathisers for the continuation, if not the reinforcement of violence. This shows that migrant communities in diverse ways could either fuel conflict or promote peace in their homeland.

In furtherance, 24 of the respondents stated that the purchase and supply of ammunitions was another form of resource spent on the Yendi chieftaincy conflict. A respondent (R6) indicated:

‘Anytime they (combatants) were short of bullets, requests were made and they were provided. They have never used their monies to buy bullets. It is surprising to know how they smuggled them into the Municipality’ (A Respondent Remark, 2019).

R6 information demonstrates the critical role played by external parties in violent and protracted conflicts. The information also implies that the nature of a given resource will determine the financier. Modern arms and ammunitions are costly to be acquired by an ordinary persons or combatants. This assertion was validated by the respondents to the effect that these weapons and ammunitions were smuggled into the conflict zone by outsiders. The implication from the finding is that attempts to ensure and sustain development in the study community will be an illusion without proper education and massive disarmament. This however, demands a collective effort from traditional authorities, combatants, security agents, conflict resolution experts and Diasporas associations. Arms and ammunitions are well-known documented in the literature as a major traditional mode of conflict financing (Annan, 2010; Capie, 2004). This study however, found other silent but critical forms of resources invested in the Yendi chieftaincy conflict.

Cash donation to participants (combatants) and funding of legal battles

Cash as a resource provides constant revenue over time to combatants (Mitchell, 2005).Twenty-two (22) respondents expressed that combatants were given cash which motivated them to wage the Yendi chieftaincy conflict. A respondent (R4) remarked:

‘People used to get a lot of money from these financiers to sustain them and their families’. Apparently the monies were given to the people to motivate them to fight their enemies’.

Corroborating, further 20 respondents indicated that support and funding of legal battles at the courts was another form of resource spent on the Yendi chieftaincy conflict. A respondent (R7) remarked:

‘Why do you think we were going to court? Do you think we will use our own money to fight at the court? We had some people who were helping us when it comes to financing on legal matters’ (A Respondent Remark, 2019).

R7’s response showed that external support in the form of cash donation actually motivated the combatants and also helped the feuding gates to pursue court cases. This as the information gathered, helped in protracting both the conflict and its resolution. As the Theory of Scarcity of Positional Goods espouses, cash donation to belligerents and the support of legal tussles enabled the competing gates to mutually wage the conflict continuously with the view to prevent one another from occupying the limited covetous ‘traditional political position’ of influence. This finding is in line with Rose (2018) study which revealed that Boko Haram and Al-Shabaab terrorists’ organisations have been able to sustain their operations through financial support. The finding also agrees with the work of Wennmann (2011) which found that the wars in Kosovo and Albanian were sustained by cash transfer from Kosovo and Albanian Diaspora communities. His study revealed that cash transfer to Kosovo was done principally through cash couriers, whilst money was electronically transferred to accounts in Albania. The finding implies that the movement of a given conflict (escalation and de-escalation) is contingent upon the level of external support granted to the conflicting parties. In this regard, to sustain the gains of conflict zones, all institutions involving in money transfer should be critically monitored by the appropriate authorities.

Free fuel for participants

According to 12 respondents, free supply of fuel (petrol) to interested individuals or combatants was one way in which the Yendi chieftaincy conflict was financed. According to the respondents, members of the feuding gates and sympathisers were supplied with fuels for errands and also for burning of houses. This is what one discussant by name Courage (pseudonym) (B1) said:

‘I have ever been given a coupon for fuel just because they thought I belong to their gate. You will not believe it. This was real in our community here’ (A Respondent Interviewed, 2019).

This finding is indicative that various resources influence and sustain conflicts. What this means is that in making efforts to resolve and sustain any gains in conflict prone zones, the activities of fuel (petrol, diesel and kerosene) dealers, both commercial and petty dealers have to be closely monitored.

Provision of ideas

Effective strategy in waging conflicts requires tutorials, coaching, education and training. Nine (9) respondents were of the view that the needed resources in the form of ideas were given to combatants to make them effective in their operations. In support, this is what a key informant (K2) asserted:

‘Those with formal knowledge were able to help others in zoning and mapping the Municipality. That was why some of their events took us as a surprise’ (A key Informant Interviewed, 2019).

Conflict promotion has become an enterprise and therefore demands innovative ideas in order to succeed. In the view of Wennmann (2011), systematic combat campaigns require a high degree of tactical skill. The supply of ideas as gathered from the respondents could be seen as strategic in launching a surprise attack against an opponent. What the finding suggests is that conflict dynamics – protraction, de-escalation and termination may depend on the inventiveness of productive ideas. These ideas as a form of investment as revealed could be likened to what Kriesberg (1998) refers to as the development of innovative contentious tactics. Protracted and or destructive conflicts, thus, thrive on various ground-breaking ideas.

Machetes

McNulty (2000) writes that machete is a common weapon that many people in Africa have access to. According to six (6) respondents, machetes were provided to combatants and sympathisers to protect themselves from harm. A respondent (R8) in a laughing mood stated:

‘They supplied us machetes to fight, but some of us used them in our farms’ (A Respondent Remark, 2019.)

Corroborating, another respondent (R9) remarked:

‘We were having a blacksmith who manufactured all kinds of machetes we needed. For now he does not even want to hear anything like conflict’ (A Respondent Remark, 2019).

Supporting the assertion, a key informant (K3) stated:

‘I remember a vehicle was once stopped at Sang barrier and we realised the car was full of cutlasses. When the occupants were questioned, we were told they were sending them for farming purposes. This was quiet funny especially given the situation in which we found ourselves at that time. In deed cutlasses were supplied especially to the young ones for self defence’ (A key Informant Interviewed, 2019).

The emerging picture is that financing of conflict is not only limited to filling the pockets of combatants with money. The supply of machete, a common agricultural tool to the combatants in Yendi implies that the users required no strenuous efforts in their application for either self-defence, attack or both. This was strategic in that as Jones (2011) study revealed, the Rwandan genocide proved that old weapons could be just as effective in murdering a great number of people at ease. The relatively cheap nature of machetes means that they were easily mobilised from both within and outside the conflict zone as gathered from the respondents. The information as gathered shows that our attempt to understand the dynamics of a given conflict may require a thorough interrogation of the broad silent forms of conflict financing beyond arms investment. Machetes seemingly simple tools nonetheless are a major driver of destructive and protracted conflicts. The finding supports Chesterman (2002) study which revealed that the brutality of the Rwanda conflict in 1994 was only heightened by the use of simple ‘pangas’ (machetes) and sharpened sticks. McNulty (2000) study earlier revealed that in an effort to prepare for the genocide, agricultural tools such as the machete were imported into Rwanda in numbers that “greatly exceeded Rwanda’s agricultural needs.” This present study has also found that machetes in large quantities were brought into Yendi in addition to those manufactured locally for the purposes of arming the combatants. The revelation from the study could explain why the Yendi conflict was able to sustain for decades till January, 2019 when the standoff between the two antagonistic gates was resolved.

The information from the respondents indicates that minor voluntary financial contributions were made by indigenes from Yendi including the combatants while large portion of the resources were invested by people outside the immediate conflict environment. This idea was confirmed by a key informant who expressed that the guns used by the ordinary civilians were supplied by external parties/diasporas. This view was further validated by the information given by a section of the respondents and a key informant to the effect that cash donations, guns and ammunitions were supplied by financiers other than the combatants from Yendi. Earlier, Horowitz (2000) wrote that the conflicts in Sri Lanka, Angola and Kashmir among others have been fueled by the financial and other supports given to the rebel groups by the diaspora relations. The finding from the study is indicative that various forms of resources were invested in the Yendi chieftaincy conflict by different categories of people for obvious reasons as posited by the Theory of Scarcity of Positional Goods. Supply of guns and ammunitions may play instrumental role in conflict protraction.

Nonetheless, as this study has revealed, they are not the only means of conflict financing. As noted by Wennmann (2011), to be able to identify and seize new opportunities for peace-making, we need to broaden our study of the economic dimensions of armed groups.

CONCLUSION

Chieftaincy remains a much cherished institution in Ghana, as among the Dagomba ethic group. Nonetheless, the institution is bedeviled with protracted conflicts. This study examined the critical but unnoticed drivers of the infamous Yendi chieftaincy conflict in the Northern Region of Ghana. The study found that besides arms and ammunitions, cash donation to combatants, funding of legal battles and supply of machetes among others, principally and cumulatively, helped in protracting the Yendi chieftaincy conflict and its resolution.

POLICY IMPLICATION

The implication is that periodic disarmament exercise should collectively be carried out in Yendi and its environs by the National Peace Council (NPC), the Ghana Police Service, the Military, and National Council for Civic Education (NCCE), as well as coalition of NGOs working in peace and development of communities. The simple reason is that the availability of these resources easily creates insecurity conditions and reverses any development gains by communities.

More so, the banks operating within and outside Yendi, the activities of the local fuel dealers and savings and loans institutions should be constantly and critically monitored by the security agencies. A sectorial collaboration between the banks and the police could help foil the efforts of those who draw large sums of money only to invest in conflicts in diverse ways. The fact that various weapons and ammunitions were smuggled into the conflict zone is a manifestation of seemingly weak security arrangement. The police have to beef up their efforts, intelligence and presence to prevent possible avoidable clashes in the community.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Abokyi SN (2018). The Interface of Modern Partisan Politics and Community Conflicts in Africa: the case of Northern Ghana Conflicts. ASC Working Paper 143. The Netherlands: African Studies Centre Leiden. |

|

|

Addison T, Le Billon P, Murshed SM (2001). Finance in Conflict and Reconstruction. Journal of International Development 13(7):951-964. |

|

|

Ahorsu K, Gebe BY (2011). Governance and Security in Ghana: The Dagbon Chieftaincy Crisis. Accra, Ghana: WACSI. |

|

|

Annan K (2010). Millennium Report to UN General Assembly (UNGA). New York, USA. |

|

|

Awedoba AK (2009). An Ethnographic Studies of Northern Ghanaian Conflicts: Towards a Sustainable Peace Initiatives. Ghana: Sub-Saharan Publishers. |

|

|

Baser B, Swain A (2008). Diasporas as Peacemakers: Third Party Mediation in Homeland Conflicts. International Journal on World Peace 25(3):7-28. |

|

|

Brobbey SA (2008). The law of chieftaincy in Ghana. Accra: Advance Legal Publications (ALP). |

|

|

Brown O, Halle M, Moreno SP, Winkler S (2007). Trade, Aid and Security: An Agenda for Peace and Development (Eds.). London: Sterling, VA. |

|

|

Capie D (2004). Regional Introduction: Missing the Target? The Human Cost of Small Arms Proliferation and Misuse in Southeast Asia. In: H. Annelies., N. Simmonds, H. van de Veen (eds). Searching for Peace in Asia Pacific: An Overview of Conflict Prevention and Peace building Activities, pp.294-312. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, Incorporated. |

|

|

Chesterman S (2002). Just War or Just Peace? Humanitarian Intervention and International Law. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Duffield M (2002). Global governance and the new wars: The merging of development and security. London: Zed Books. |

|

|

Enu-Kwesi F, Tuffour KA (2010). Conflict management and peace- building in Africa: Critical lessons for peace practitioners. In: SB Kendie (Ed.), Conflict management and peace building for poverty reduction, pp. 23-47. Tamale: Centre for Continuing Education and Inter-disciplinary Research, University for Development Studies. |

|

|

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) (2012). 2010 Population and Housing Census Summary Report of Final Results. Accra: Sakoa Press Limited. |

|

|

Goldstone JA (2018). Demography, environment, and security. In Environmental conflict (pp. 84-108). Routledge. |

|

|

Gourevitch P (1998). We Wish to Inform You That Tomorrow We Will Be Killed With Our Families: Stories From Rwanda. New York: Picador. |

|

|

Hagan GP (2006). 'Epilogue' Chieftaincy in Ghana: Culture, Governance and Development. In: IK Odotei, AK. Awedoba (Eds.). Chieftaincy in Ghana: Culture, Governance and Development, pp. 663-673. Accra: Sub-Sahara Publishers. |

|

|

Horowitz DL (2000). Ethnic Group in Conflict. Berkeley: University of California Press. |

|

|

Ibrahim AR (2018). Transforming the Dagbon Chieftaincy Conflict in Ghana: Perception on the use of Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR). Florida: Nova Southeastern University. |

|

|

International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) (2016). ICYM Friday Roundup: Protracted Conflicts September 9, 2016. Available: |

|

|

Jones A (2011). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction, Second Edition. New York: Routledge. |

|

|

Kaldor M (2001). New and Old Wars: Organized Violence in a Global Era. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Polity Press. |

|

|

Kendie SB, Bukari KN (2012). Conflict and its effects on development in the Bawku Traditional Area. Journal of Arts and Social Sciences 1(1):1-9. |

|

|

Kinyua D (2017). Conflict Financing and Civil War in Africa: Case Study of Democratic Republic of Congo. Nairobi: Doctoral dissertation, University of Nairobi. |

|

|

Kriesberg L (1998). Constructive Conflicts: From Escalation to Resolution. Maryland: Rowman. |

|

|

Mahama I (2003). Ethnic Conflicts in Northern Ghana. Tamale-Ghana: Cyber Systems. |

|

|

Marfo S, Musah H, Abukari A (2019). Chieftaincy Conflicts and Food and Livestock Production Challenges: An Examination of the Situation in Bimbilla, Ghana. ADRRI Journal of Arts and Social Sciences 7(4):11-34. |

|

|

McNulty M (2000). French arms, war and genocide in Rwanda. Crime Law and Social Change 33(1):105-129. |

|

|

Mitchell CR (1981). Structure of International Conflict. London: Macmillan Press Limited. |

|

|

Mitchell CR (2005). Conflict, Social Change and Conflict Resolution. An Enquiry. Research Center for Constructive Conflict Management. Available: |

|

|

Nweke K (2012). The Role of Traditional Institutions of Governance in Managing Social Conflicts in Nigeria's Oil-Rich Niger Delta Communities: Imperatives of Peace-Building Process in the Post-Amnesty Era. British Journal of Arts and Social Sciences 5(2):202-219. |

|

|

Odotei IK (2006). Women in Male Corridors of Power. In: IK Odotei, AK Awedoba (Eds.). Chieftaincy in Ghana: Culture, Governance and Development 81:145-168. Sub-Saharan Publishers, Accra, Ghana. |

|

|

Owusu-Ansah D, McFarland DM (1995). Historical Dictionary of Ghana (2nd edition). London: The Scarecrow Press, Incorporated. |

|

|

Rose G (2018). Terrorism Financing in Foreign Conflict Zones. Counter Terrorist Trends and Analyses 10(2):11-16. |

|

|

Simmons E (2013). Harvesting Peace: Food security, conflict, and cooperation. Environmental Change and Security Program Report 14(3):0_2. |

|

|

Sirleaf EJ (2011). The Challenges of Post-war Reconstruction-The Liberian Experience. Event at Chatham House. President of the Republic of Liberia, 13. |

|

|

Staniland M (1975). The Lions of Dagbon: Political Change in Northern Ghana. New York: Cambridge University Press. |

|

|

The Wuaku Commission Report, C.I.36 (2002). Accra, Ghana. |

|

|

Tonah S (2012). The Politicization of Chieftaincy Conflicts: The Case of Dagbon, Northern Ghana. Nordic Journal of African Studies 21(1):1-20. |

|

|

United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECF) (2016). Human and Economic Cost of Conflict in the Horn of Africa: Implications for a Transformative and Inclusive Post-Conflict Development. |

|

|

Urdal H (2012). A clash of Generations? Youth Burges and Political Violence. United Nations Population Division Expert Paper No. 2012/1. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. |

|

|

Verwimp P (2006). Machetes and Firearms: The Organization of Massacres in Rwanda. Journal of Peace Research 43(1):5-22. |

|

|

Wennmann A (2007). The Political Economy of Conflict Financing: A Comprehensive Approach beyond Natural Resources. Global Governance 13(3):427-444. |

|

|

Wennmann A (2011). Economic dimensions of armed groups: Profiling the Financing, Costs, and Agendas and their Implications for Mediated Engagements. International Review of the Red Cross 93(882):333-352. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0