Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

In more than six years, Russia expanded its presence in Africa sevenfold, starting with four (4) countries in 2015 and reaching 25 by 2021, including the Central African Republic (CAR). In the CAR, Russia became a major actor alongside the fourteen (14) armed groups, the United Nations Blue Helmets, and the Central African Army forces. While Moscow is involved in security issues and military diplomacy with lucrative reward, China is engaged in several development activities. This study examines Russia’s and China’s motivations, interests, and strategies in the CAR. The authors use the New Scramble for Africa literature as their theoretical lens. The overall objective of this paper is to foster a greater understanding of Russia’s and China’s role in the CAR where armed groups control 60% of the resource-rich areas. The armed groups’ predatory activities and Moscow’s realist policy in the CAR derailed the peace process via direct confrontations between the great power and armed groups. These confrontations escalated the geopolitical rift between France and Russia over CAR. Our findings indicate that Russia and China will increasingly become engaged in strategic competition for the resources of CAR, with detrimental consequences for peace and prosperity in the CAR.

Key words: Russia, China, armed groups, minerals, Central African Republic, United Nations, New Scramble for Africa.

INTRODUCTION

The Central African Republic (CAR) experienced its fifth military coup in 2013, perpetrated by the Seleka armed group. The coup escalated into a protracted and pervasive civil war with serious crimes perpetrated by insurgents. About 190,000 people fled to neighboring countries, and 850,000–930,000 became internally displaced persons In the early stages of the conflict, the international community (African Union, France and the United Nations) deployed troops to halt the conflict and sustain peace. In 2016, France disengaged and withdrew its troops from the CAR. One year later, Russia stepped in with authorization from the UN Security Council, which approved an exemption to the arms embargo imposed on the CAR in response to conflict. Moscow then provided arms and instructors to the EU training battalion.

In 2019, Russia sponsored the Khartoum peace deal between the government of the CAR and fourteen (14) armed groups. Some analysts contend that the Russian leader Vladimir Putin’s foreign policy was aimed to preserve state sovereignty and self-determination.

However, critics assume that Moscow was promoting its own economic interests under the guise of promoting state sovereignty and protecting legitimate authorities. Kimberly (2019) stated that Moscow’s true ambition was to access the CAR's natural resources, including oil, diamonds, uranium, gas and other raw materials. Other scholars argue that Russia’s realist engagement in fragile states will not stand in light of its fragile economic situation. Paris and Washington’s military disengagement in 2016 paved the way for Russia and China to expand and reinforce their influence in the CAR. This paper discusses Moscow’s and Pekin’s strategies in the conflict affected-country (Kimberly, 2019).

The paper will address the following questions: What are Russia and China’s policies in the CAR? Why is Russia and China interested in poor and conflict affected countries in Central Africa? Do Russia and China cooperate or compete in the CAR? What impact does China’s and Russia’s presence in CAR have on peace and development prospects?

Theoretical framework: The new scramble for Africa and great power competition

The first ‘scramble for Africa’ was carried out by European powers competing for resources in the region in the late 19th century (Eberechi, 2009). This resulted in the 1884-1885 Berlin conference that partitioned the continent. Needless to say, this was not in the interest of Africans. In this first scramble for Africa, colonialism caused significant and enduring damage to African societies. The activity of great powers in the African continent today has been termed a ‘new scramble for Africa’. Great powers competing in this scramble today include China, Russia, the U.S., Turkey, India, and the European powers. These powers are not competing for territory, but instead for influence, access to natural resources, and trade opportunities (Harms, 2019).

Of these powers, China has invested the most in Africa since the turn of the century (Poplak, 2016). China’s investments in African countries range in billions of dollars (Poplak, 2016). For Pekin and other emerging economies, Africa holds vast amounts of natural resources that are of huge potential to them. China’s strategy in Africa to date has included the use of soft power to promote language and culture for political and economic gain (Salomone, 2022), alongside foreign direct investments in Africa to ensure a steady supply of resources in favorable economic terms (Carpintero et al., 2016). This strategy has been termed one of ‘smart power’, using moderated hard power through economic investment, in conjunction with soft power to promote its culture and improve the image of China in Africa (Salomone, 2022).China is not the only great power taking part in the new scramble for Africa. Over recent years, Russia has been stepping up its activities on the continent. This was shown through the 2019 Russia-Africa Economic Forum, which brought together some 43 African leaders with the aim ‘to foster political, economic, and cultural cooperation’ (Harding and Burke, 2019). During the Cold War, The Soviet Union’s objectives in Africa were tied to maintaining its image as a global superpower and competing for influence with other superpowers of the time (Gathara, 2019) by supporting African leaders’ fight for independence from colonial rule. Today this goal of maintaining influence at the expense of other great powers remains largely unchanged (Gathara, 2019). Russia sees Africa as a major trade opportunity and its strategy revolves around establishing military and security projects in African countries as well as facilitating the extraction of natural resources (Adam, 2018).

Much has been written about China’s investments and influence campaigns in Africa over recent decades (Rotberg, 2009; Zhang et al., 2016; Tan?Mullins et al., 2010). China has been termed the ‘new dominant foreign power in Africa’ (Adam, 2018). China appears to be leading the new scramble for Africa, yet it is decidedly less clear how Russia fits into this picture. Competition between China and Western powers in Africa can be seen as a ‘resource-hungry China’ up against the West which views China’s growing influence in the region as part of emerging great power competition for global hegemony (Gathara, 2019). Russia too has its own well-documented conflicts with the West, so its competition for influence with the US-Europe alliance in Africa is unsurprising.

What is of interest is how Russia and China see each other’s activities on the African continent. The increasingly close relationship between the two great powers, one described by both powers as a ‘no limits’ partnership (Munroe et al., 2022), should imply cooperation and coordination in influence activities on the African continent. However, the dynamics of the new scramble for Africa does not point toward cooperation and partnership, rather they would seem to push in the direction of competition between great powers vying for influence on the continent. Spivak (2019) questions whether Moscow’s increased actions in Africa, in particular the arms sales, will destabilize the region and cause problems for achieving China’s own strategic goals. We see the geo-political implications of the new scramble for Africa on Russia – China relations as a question left to be examined in the literature.

Moreover, it is unclear how similar the strategies of Russia and China are. Broadly speaking, most scholars agree that these great powers seek greater influence on the African continent. But how their strategies differ and what effect this has on African countries remains unclear. Adebajo has questioned whether Russia’s participation in the new scramble for Africa is a bid to promote stability and good intra-continental relations on the continent, or whether Russia’s actions on the continent are to the detriment of African countries (Adebajo, 2020). Though China’s role on the continent has been well documented, Russia’s actions have been less so, leaving a gap in the literature. What are Russia’s strategy and aims in the new scramble for Africa and how do these differ from those of other great powers? To what extent do they mirror China’s strategy?

Finally, the overriding question of the new scramble for Africa literature is what effect this has on African countries. Africa should be wary of such intense interest by great powers: ‘Historically, when external powers have eyed Africa and seen it as a source for raw materials or markets, Africans themselves often pay the price’ (Harms, 2019). In this new scramble for Africa, it remains unclear whether this is the birth of a new form of colonialism, one that will leave the continent in tatters (Poplak, 2016), or instead whether Africa will be able to shake off colonialism and take advantage of this renewed interest in Africa to bring critical investment for development (Snr, 2021).

The theoretical lens places the actions of Russia and China in the context of the new scramble for Africa taking place between great powers in the 21st century. It also includes realism to analyze the geopolitical dynamics of this competition and what it tells us about the relationship between China and Russia today, as well as how this relationship might change in the future. George Mchedlishvili finds "pure realism in [Moscow's] policy as it gives primacy to the interests of the state.’’ He stressed that Russia's current confrontation with the West under "the New Cold War (or Cold War 2.0) will be suicidal for Russia's long-term development.” Thornike, on his side, believes that "Russia is undertaking a hybrid war to create a precondition for war, to conquer territory and to obtain benefits." He further contends that "the hybrid war allows Russia to minimize the need to use military force while achieving its foreign policy goals." Thornike explains that "a hybrid war removes the traditional edge between war and peace and is constantly going on and occupying the territory without open military good example. Russian Special Forces (…) occupied Crimea without shedding blood. The scholar stresses that "Hybrid war means permanent war all over the world, where there are no red lines and no bans." In that respect, he refers to "the Chief of Staff of the Russian Army in 2013, who stated that in the ‘New Generation War’, military force will be used covertly, without official declaration."

METHODOLOGY

The methodology is a comparative case study analysis of Russia and China’s strategies in CAR. When undertaking comparative case studies, the aim is to draw causal inferences by looking for two modes of case comparison: ‘the researcher looks for causal conditions that are the same between two cases that have the same outcome’ or ‘the researcher looks for antecedent conditions that differ in two cases that have different outcomes’ (Ahn, 2018). This methodology will allow us to analyze the similarities and differences in these two great powers’ strategies.

Process tracing will be used within case studies to determine causality. This is an analytical technique often used in comparative case studies (Goodrick, 2019). Process tracing is ‘an analytic tool for drawing descriptive and causal inferences from diagnostic pieces of evidence – often understood as part of a temporal sequence of events or phenomena’ (Collier, 2011). ‘The goal is to document whether the sequence of events or processes within the case fits those predicted by alternative explanations of the case’ (Bennett, 2008).

Techniques of document analysis are used when analyzing source material. ‘Document analysis involves skimming (superficial examination), reading (thorough examination), and interpretation. This iterative process combines elements of content analysis and thematic analysis’ (Bowen, 2009). The source material is a combination of literature, media reports and investigations, and government sources.

Qualitative methodology is best suited to the study conducted and allowed to incorporate a wide range of material and an extended time frame needed to deal with the complex topic at hand.

Russia strategy in the CAR

The active cooperation process with the CAR started On October 7, 2017, when Firmin Ngrebada, President Touadera's chief of staff, met with the Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov in Sochi, Russia (Dukhan, 2020). Following that meeting, Russia appealed to the UN "to make an exemption to arms embargo on the Central African Republic so that Moscow could provide weapons to two EU-trained battalions of its [CAR] military forces” (Korybko, 2017). Russia convinced the UN Security Council of its commitment to comply with the council requirements regarding "arms imports and vowed to store them in new containers under tight security" with serial numbers "for each unit so that they can be traced if they end up in the wrong hands" (Korybko, 2017). Samuel Ramani views Russia’s military diplomacy as a mean to weaken the UN sanction regime particularly arm embargo and diamond export imposed to the country through 2127(2013) United Nations Security council resolution. He recalls that Moscow lobby resulted in the lift of restrictions on the CAR diamond exports (Ramani, 2021).

In 2018, Touadera met Putin in Russia to formalize their relationship. Analysts indicate that the president of the CAR negotiated for protection and pacification of the country in exchange for access to natural resources. Thus Putin sponsored the Wagner Group, a (Russian shadow army), (Dukhan, 2020) and created an ideal environment in which to access the CAR's vast stores of natural resources. Goodison stressed that Moscow establish[ed] its presence in Africa's geostrategic heartland" for its own gain (Korybko, 2017). In parallel with military diplomacy, Moscow also appeared to be involved in the UN peace Agenda in the CAR. Further, the Russian Foreign Ministry adimts claimed that Russia wishes to ‘strengthen the national security units of CAR’ and secure mutually beneficial mining contracts (Ramani, 2021).

In the CAR peace process, Moscow wanted to be viewed as a peacemaker, who succeeded where western powers failed to foster a peace deal between the government and armed groups. In fact, the failure of the Sant' Egidio Peace Accord, signed in Italy in 2017, fostered Moscow’s political will to play a leading role in peacemaking in the CAR. Prior to the negotiation process in Khartoum (Sudan), Russia liaised with armed group leadership and informed them of their intentions. Russia engaged with the main stakeholders at domestic and regional levels to obtain political support from the main actors, including the armed groups of the CAR government and Omar al-Bashir, the former president of Sudan, Russia’s regional ally. As a result, a Peace Agreement was concluded in Khartoum and signed in Bangui in February 2019. Through an active cooperation with the African Union and the UN on national reconciliation in CAR, Russia burnished its reputation as a diplomatic arbiter in the CAR (Ramani, 2021).

At early stages of the peace process, Moscow concluded a deal with the major armed groups, guided by its non-ideological policy Russia had ambitions to support both armed groups and the government of the CAR in the security sector. This hedging strategy mirrors Russia’s behaviour in Libya, as Moscow militarily supports the Libyan National Army chief, Khalifa Haftar, while engaging with other rival factions (Ramani, 2021). In in fact, in July 2018, Russia proceeded with military training for the armed groups with "Approximately two hundred (200) FPRC elements headed to Amd-Dafock (65 km to Sudan)." Trainees were selected “across areas under the FPRC's influence.” During a five-month period, extensive training was provided in advanced weaponry, vehicle operation, and paramedic instruction to 600 ex-Seleka rebels in Sudan (Dabanga, 2018). A tight collaboration was observed between Moscow and the armed groups when 19 Russian trucks were spotted in Birao (85 km from Sudan) on May 12, 2018. These trucks were escorted by 30 armed the FPRC elements under the command of FPRC General Ibrahim. That day the Russian delegation donated assorted drugs and medical materials to Birao Hospital. The close collaboration between the Russian Paramilitary organization (Wagner) and the CAR major armed groups explains Russia’s nonideological approach consisted of maintaining good relationships both with government and nonstate actors (Sadden et al., 2017).

In parallel, Russia provided arms, training, and protection to Touadéra, Government amidst "mistrustful sentiment of Western military presence in the country" (Plichta, 2018). The initial agreement between Russia and the CAR included "five military officers and 170 civilian instructors, along with more than 5,000 AK-47s, sniper rifles and grenade launchers" (Calzoni, 2018) Putin’s provision of arms to the government of the CAR frustrated rebel factions, who started building their own weapon stockpiles. Russia’s nonideological engagement in the CAR was challenged by armed groups that suspected Russia had self-serving intentions.

After the Khartoum negotiations that resulted in the peace accord in Bangui, armed groups protested the new government's reshuffling, which left them underrepresented. Even after they were granted lucrative government jobs, they persisted in making these claims. Given this state of unrest, pro-French actors and several armed groups planned to overthrow President Touadéra and weaken Russia's presence. To counter these threats, Touadéra and Russia supported three armed group leaders, Hamza Toumou Deya from Mouvement des liberateurs centrafricains pour la justice (MLCJ), Herbert Djono Gontran Ahaba and Moustapha Maloum (alias Zakaria Damane) Rassemblement pour la paix en republic centrafricaine (RPRC), believing these allies would help to weaken the FPRC presence in the northern and western regions and could regain control of strategic resource-rich areas important for Russian expansionism (Dukhan, 2017). In August 2019, opposition to the MLCJ and FPRC in the Vakaga region led to violent clashes, resulting in the killing of dozens of civilians (Dukhan, 2018). The 2020 presidential election heightened tensions, and former President Francois Bozize created a new rebel group, named CPC, which sought to remove incumbent President Faustin Archange Touadera from power. Supporting President Touadera for reelection, Moscow’s strategy aimed at consolidating its investments and contracts in the CAR by ensuring Touadéra's re-election.

In December 2020, armed groups launched a military offensive against the CAR capital city. The situation alarmed Russia, and to counter the offensive, Moscow increased its security forces. During the armed struggle against armed group Russia ambassador warned the former president: "[François Bozizé] should renounce the armed struggle; otherwise, he would be neutralized by the armed forces," (Bushuev and Topona, (2021)) warned Russian Ambassador to the CAR, Vladimir Titorenko. Officially, Moscow stated that it deployed 535 military experts; in fact, the number was much higher, as the Russian private security firm, the Wagner group, employed more than 1,000 people in the region. According to local sources, Russian paramilitaries, troops from Rwanda, and CAR security forces were seen on the front-line fighting rebels. Because of robust military operations, the government recovered most of former rebel strongholds. Amidst criticism of its unilateral intervention in the CAR, Russia's Foreign Minister indicated to the media DW that "Military specialists from Russia are sent to the country as per UN Security Council guidelines" (Bushuev and Topona, (2021)). In a report published on March 30, the UN human rights office expressed alarm to the international community over human rights violations by Russian mercenaries, citing

"… the interconnected roles of Sewa Security Services, Russian-owned Lobaye Invest SARLU, and the Wagner Group… [and, most importantly,] their connections to a series of violent attacks that have occurred since the presidential elections on December 27, 2020…"

Economic interests

In 2016, CAR authorities were allowed to export diamonds from five conflict-free 'green zones'. Russia served as 2020 chair of the Kimberley Process, which monitors ethics of exporting diamonds. As Russian state-aligned companies, such as diamond giant Alrosa and Prigozhin-aligned M-Invest, seek to expand their commercial deals in CAR.

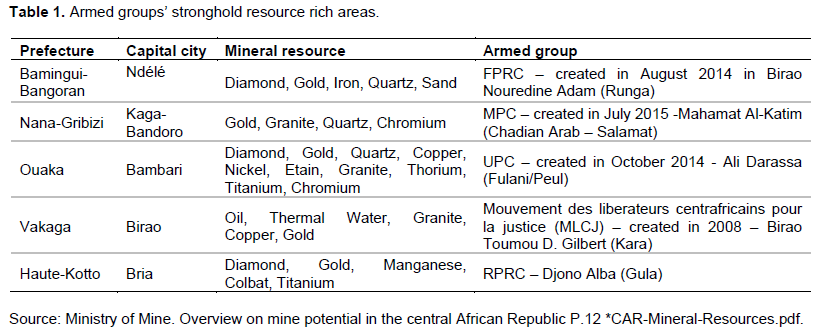

Nathalia Dukhan stressed that the CAR gave "prospecting-mining exploration concessions" to Russia (Schreck, 2018), and Putin positioned himself to profit from CAR's uranium alone. Furthermore, Goodison recalled that in 2006, 39,603 tons of uranium were mined worldwide, but demand was 66,500 tons and will continue to increase in the coming years" (WISE, 2018). Russia to conquer armed groups strongholds includingVakaga, Bamingui-Bangoran, Ouham-Ouham Pende, Nana-Gribizi, Haute-Kotto, Nana-Mambere and Mambere Kadei, Ouaka which rich areas in oil, gold, and diamonds and are controlled by the FPRC, anti-balaka, MPC, RPRC and UPC armed groups. Moscow’s military strategy in the CAR aims to withdraw armed groups from resource-rich areas to allow the exploitation of minerals. According to Goodison, Bakouma mine ownership reveals Russia's competition for uranium in the region. He stresses that only 10% of the Bakouma mine is owned by the government of the CAR, while the other 90% is held by Uramin Incorporated (WISE, 2018). Forty-nine percent of the Uramin is held by the China Guangdong Nuclear Power Company (WISE, 2010), while Areva, the French multinational corporation, owns the remaining 51%; its investors include Japan and the Kazakh government owned KazAtomProm (WISE, 2010). In 2017, just as Russia was intervening in the CAR, a second Chinese company sought to buy Bakouma shares from Areva but failed (WISE, 2010). In fact, Uranium was discovered in Bakouma in the 1960s, and its reserves are estimated at 16,765 tons of metal uranium with a rate of 0.255% uranium. Uranium has also been found along the CAR's southern border between Mobaye and Bangassou (IPIS, 2017). The CAR was an opportunity for Russia to expand its influence in Africa and pursue its economic goals. Table 1 shows the armed groups stronghold resource rich areas.

China’s strategy in the CAR

China’s role in the CAR is growing, but it is not nearly as significant as Russia’s (Minney et al., 2019). China has had relations with the CAR stretching back decades. It was the first country to assist the CAR with a $2.5 million grant in April 2003 after Francois Bozize seized power from President Ange-Felix (IRIN News, 2004). This was followed by a $2.5 million interest free loan in June 2003 and a further $2 million in November, along with $83,000 in aid (IRIN News, 2004). Loans and aid of this kind have long been a feature of China’s strategy in Africa. Over the next decade, China financed multiple development projects in the CAR. In 2005, Chinese state-owned Import-Export Bank agreed to provide funding for the supply and installation of mobile and fixed networks covering the CAR at a cost of $67 million, to be built through Chinese state-owned ZTE (Foster et al., 2009). In 2003, China also financed a 20,000-seat stadium in Bangui (AIDDATA, n.d.). Yet Chinese banks stopped providing major loans to the CAR in 2011 (Minney et al., 2019), as the country descended into civil war.

This was not before Bozize awarded China National Petroleum Corporation the rights to explore for oil at Boromata, in the country’s northeast near the border with Chad (Aboa and Ngoupana, 2013). Oil exploration is key to the story of China’s involvement in the CAR and its involvement with armed groups post the 2011 coup. A 2016 UN Report alleged that Chinese oil company PITAL International Petroleum was financing armed groups in the CAR. The Chinese oil company acted through a private security company FIT Protection to pay $US40,000 to an ex-Séléka faction known as the Front Populaire pour la renaissance pour la centrafrique (FPRC) to respect an 80km security permitter and not carry out attacks on its facilities at Gaskai in the north of the country (Republic, 2016). This was in violation of a UN sanctions regime (Republic, 2016). An anti-corruption group, Global Witness, reported that European and Chinese timber companies together paid 3.4 million Euros to mostly Seleka rebel groups in 2013 for security and checkpoints (Witness, 2015).

To achieve its ambitious goal of becoming carbon neutral by 2060, China is investing in its nuclear energy territories (DeBoom, 2021). Countries in Africa, such as Namibia, have seen large investments by China to mine their uranium deposits (DeBoom, 2021). As previously mentioned, China’s Guangdong Nuclear Power Company owns 49% of the uranium portion at an established mine in Bakouma. In 2017, just as Russia was intervening in the CAR, another Chinese Company sought to buy shares in the mine and failed to do so (Goodison, 2019). Many of the resource rich regions in the north of the country where mineral and oil deposits lie are controlled by rebel groups that Russia is engaged with (Goodison, 2019). The increasing potential for Beijing and Moscow to view each as rivals rather than partners in the scramble for the CAR’s mineral wealth is clear.

Wikileaks released documents in 2016 that allege to show corruption by both Western and Chinese companies in a rivalry over claims to the CAR’s uranium and other mineral wealth. Allegations of corrupt mining rights and mining contracts, and damage caused to the environment, again point to China’s involvement in the exploitation of the CAR. Documents revealed by Wikileaks allege to show China’s state owned defence company Poly Technologies (PTI) tried to invest in the CAR, ‘probably within the framework of a hidden weapons agreement thought to feed the Central African Republic Civil War in spite of global sanctions’ (WikiLeaks, 2016). Documents show contracts between PTI and CAR’s government in 2007 and 2011 for oil exploration permits and bonuses. Further 2015 documents show the contractual situation between the. CAR and PTI and further business dealings (WikiLeaks, 2016).

Several Chinese companies are involved in mining activities across the CAR. Multiple reports and investigations have raised human rights and environmental concerns related to the practice of these companies. A 2019 report released following a parliamentary commission of inquiry in the CAR recommended that four Chinese companies Tian Roun, Tian Xiang, SMC Mao, and Meng, stop mining for gold in Bozoum in the north of the country (Ngounou, 2019). These companies had caused extensive pollution and degradation of the environment, with the report entitled “Ecological Disaster” (Ngounou, 2019). Such activities highlight the concern among many that China’s actions in Africa, seen through state owned and affiliated companies are exploitative and damaging for local populations. In this instance, Chinese mining companies caused great damage to the local environment and communities.

An Amnesty International report revealed that following the departure of these companies in April 2020, seven people died at the abandoned mining sites and there was a failure to restore the Ouham river (Amnesty International, 2020). In all ‘Three government reports and other testimony – corroborated by satellite imagery, photographs and videos – attest to profound changes to the Ouham River’ (Amnesty International, 2020). China’s exploitative activities in the CAR indicate that commercial activities of foreign companies taking part in the New Scramble for Africa should be viewed with skepticism and require oversight to ensure compliance with international environmental and human rights regulations.

Energy

In August 2021, authorities inaugurated a new thermal power plant in Bangui (Africanews, 2021). For the first time since 1967, CAR saw a significant increase in its power grid thanks to funding from the African Development Bank along with Sino-Centrafrican cooperation (Africanews, 2021). In a country where only 10% of the population has access to electricity (Africanews, 2021), projects to develop the national power supply are desperately needed. China’s state-owned Shanxi Construction Investment Group Co Ltd signed an engineering, procurement and construction contract in December 2021 to build a 25MWp solar PV plant in Bagui (Energy, 2021). The project is being funded by the World Bank Group’s International Development Association at a cost of $65m, with construction expected to begin in June 2022 (Energy, 2021).

Chinese companies have been filling the need of the CAR to develop its energy grid. This could be seen most plainly during the visit by Faustin-Archange Touadéra to China for the China Africa Forum Summit in September 2018 (Takouleu, 2018). On the sidelines of this summit, the CAR signed an agreement with state owned China Gezhouaba Group Company for the reconstruction of the Boali II hydroelectric power plant (Takouleu, 2018). Located 105km from Bangui, the project will aim to increase generating capacity by 50% and will be supported by the African Development Bank (Takouleu, 2018).

This investment in the CAR’s energy infrastructure shows the potential economic investments China can make in the CAR, above those offered by Russia. If China flexes its economic muscles it is unlikely Russia will be able to compete.

China’s Outlook in the CAR

Over recent years, there are indications that China is looking to develop its relationship and influence with the CAR. In 2021, the CAR became one of the latest African countries to sign a Belt and Road Cooperation Agreement with China. At the signing ceremony, China presented medical aid to combat COVID 19 (Opali, 2021), this not being the first time China had donated such supplies to the CAR during the pandemic (CIDCA, 2020). The significance of the Belt and Road Initiative reaching the CAR can be seen through this lens of aid and development. The agreement signals a willingness and desire from both Bangui and Peking to strengthen the economic relationship between the two countries.

China has been building its cultural influence in the CAR. In 2019, China unveiled a China-CAR Friendship village, 30km away from the capital (Republic E. o., 2019). In May 2021, a Confucius Institute was established at the University of Bangui (Opali, 2021). These soft power tactics of cultural influence and aid appear part of a strategy on the part of Beijing to cultivate a stronger relationship with the Touadera government.

The track record of China’s involvement in the CAR shows an ongoing interest from Chinese companies in the mineral wealth of the country. There are no indications this will change. The effort by Peking to bring the CAR into its broader foreign policy vision in Africa, seen through the Belt and Road Initiative, is an indication that China is not prepared to leave the mineral wealth of the CAR for Moscow to exploit. Increasing soft-power tactics, seen through cultural initiatives, and hard power tactics, through economic investment in developing the CAR (particularly in its energy sector) could be part of a coordinated strategy on the part of China to foster a stronger relationship with the Toudera government and achieve for itself lucrative mining contracts. Chinese companies have a history of oil exploration in neighboring Chad, as well as Sudan. The story of China – Sudan relations is relevant for several reasons, not least because China’s interest in Sudan was directly correlated to its mineral wealth. When South Sudan split from the country in 2011 and took 80% of the united country’s mineral wealth, China’s investment in Sudan over the next decade dropped dramatically, indicating much less interest in Sudan on the part of China’s policymakers (Patey and Olander, 2021). Peking sees opportunities in the CAR and there are no indications it is prepared to walk away and leave these to Moscow.

FINDINGS

The findings of this study show that Russia and China employ contrasting strategies in the CAR. Russia is engaged in providing security assistance to the CAR in exchange for lucrative resource opportunities. China is focused on development investment in energy, water, and infrastructure and using some soft power methods to attain influence. It also appears interested in attaining its part of the rich mineral wealth of the CAR. China does not compete with Russia in providing security assistance, and so too Russia leaves development of the CAR’s infrastructure largely to China. However, the goals of each country are very similar: they both aim to gain influence in the CAR and position themselves and their state owned or associated companies in the best position to take advantage of the extensive resources in the CAR.

Behind each strategy is a hard-headed realism. The motivation behind each countries interest in the CAR is power, not just economic power gained from the resource wealth of the CAR, but also wider geo-political power that comes with establishing influence on the African continent. China’s influence campaign extends across the continent as a part of its Belt and Road Initiative. In this respect, China’s actions in the CAR are part of a broader strategy to gain influence and power across the continent of Africa. Russia has too shown a willingness to expand its influence across Africa and perhaps the CAR is a model for further influence activities they may have planned, such as those taking place in Mali. Realism fits well with the new scramble for Africa literature because it gives insight into what aims foreign countries are likely to have when interfering on the African continent, as well as what means they are likely to employ.

The findings do not show that Russia and China have been competing with each other in the CAR in any official capacity. To this date, Russia and China appear content to leave each other to their own separate influence campaigns in the CAR, focused on security and development respectively. However, indications are that this could change in the years ahead. The goals of each country in the CAR are inherently competitive, particularly as it relates to resource exploitation. As a result, this may become seen as a zero-sum game. A 2021 investigative report found that Russian and Chinese miners had been clashing at various mining sites in the CAR (Etahoben, 2021). Chinese miners were chased away from mining sites by a convoy of Russian vehicles accompanied by Wagner mercenaries, and later informed by these mercenaries that the mine now belonged to the Russians (Etahoben, 2021). Such instances do not bode well for future cooperation between Russia and China in the CAR. The more the Wagner constructed security apparatus destabilizes China’s commercial activities in the CAR, either through facilitating the disruptive activities of armed groups or by actively seizing resources themselves, the more strained the relationship will become. Predictions of increased Sino-Russian cooperation at a global level may be warranted (RADIN et al., 2021). However, in Africa, and particularly in the CAR, the reverse appears a real possibility.

The CAR shows that there is an unstable foundation to the Russia-China relationship in Africa. Each country is engaged in a scramble for resources and influence on the continent that put it in direct competition with the other. Whether they can find a way to maintain separate spheres of influence remains to be seen, but, at least as it relates to the CAR, they show few signs of cooperation. We are pessimistic about the likelihood of these powers avoiding more direct forms of competition in the future, given that both countries have shown an interest in increasing their involvement in the CAR.

Finally, the findings confirm the argument within the new scramble for Africa literature that Africans themselves should be concerned about the renewed interest of great powers on their continent. Russia’s actions, particularly through the Wagner group, betray little respect for the human rights of the people of the CAR and it is questionable what benefit they have brought to the security infrastructure there. The benefit of China’s development projects may be sizeable given the desperate need of the CAR to develop its infrastructure. Whether China maintains its efforts as a stabilizing partner for sustainable economic development in the CAR once the resource opportunities in the CAR begin to disappear, is questionable. The impact of Chinese mining companies has been shown to have detrimental effects on the people and environment of the CAR, indicating a tendency on the part of China to view and treat the people of the CAR as a resource to exploit. If competition between Russia and China develops in the CAR there is a likelihood of increased exploitation on the horizon for the people of the CAR. Despite their official statements, Russia and China display little regard for anything other than gaining power and influence in the CAR, at whatever cost this might come to the people of the CAR.

CONCLUSION

Russia has become a key player in the CAR crisis through its diplomatic actions at the UN Security Council. Moscow provided political support and helped the CAR government and armed groups reach a peace agreement in 2019. With its non-ideological approach at the beginning, Russia entered smoothly into CAR’s stronghold areas. Major armed groups’ leaders, FPRC Nouredine Adam, UPC Ali Darassa and MPC Mahamat Al-Katim have opened their doors to Russian representatives in their strongholds. Hundreds of armed group elements were trained by Russian instructors in Sudan, but the relationship between these actors eroded when the nonstate armed groups realized that Russia was providing the same services to the government of the CAR. Moscow with its shadow army Wagner is making profit in the CAR with lucrative business in the country. Security provisions in exchange of natural resources and cash policy will be in the long run to undermine the CAR economy and development ambitions.

Compared to its activities in other countries in the region, China’s involvement in the CAR has been limited. There are signs that this is changing. As Chinese state-owned companies increase investments in the CAR and the Chinese government builds its soft power initiatives, the role and presence of China in the CAR will develop. Just as Russia does, China sees opportunities in the CAR. The extensive resources of the CAR are a lucrative prospect for any developing economy. So for the potential to gain a foothold in Central Africa and expand its influence further across the continent may be part of a larger geo-political plan China has. The question that arises is; will China see Russia as standing in the way? Both powers have gone to great lengths to emphasize the strength of their relationship at a macro level, but their activities in the CAR could betray the reality that rather than cooperation, the future of this relationship will be one of competition and at least in relation to activities on the African continent.

Such an eventuality would further confirm the new scramble for Africa literature. The activities of Russia and China in the CAR show the utility of using this theory to understand great power activities on the African continent in the 21st century. Exploitation of the CAR is highly likely to increase when great powers come to see it as a resource to exploit or a prize as a part of a larger geopolitical game. The competition between powers in this scramble for Africa only increases the likelihood of exploitation, as is taking place in the CAR. As long as these powers see opportunities in the CAR, they will maintain their influence campaigns, to the detriment of the people of the CAR.

CONFLICT OF INTRESTS

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Aboa A, Ngoupana PM (2013). Central African Republic coup leader says will review resource deals. Reuters. |

|

|

Adam AH (2018). Are we witnessing a 'new scramble for Africa'? Al Jazeera. |

|

|

Adebajo T (2020). A New Doctrine? Understanding Russia and the New Scramble for Africa. The Republic. |

|

|

Africanews R (2021). CAR: Authorities inaugurate new thermal plant in Bangui. africanews: |

|

|

Ahn T (2018). The Return of the Qualitative Case Study: The Impact of the Presidency and Congress on US Policy Toward North Korea. In A. Kachuyevski, & L. M. Samuel (Eds.), Doing Qualitative Research in Politics. New York: Springer. Pp. 35-52. |

|

|

AIDDATA (n.d.). Chinese Government provides RMB 75 million interest-free loan for Barthélemy Boganda Sports Complex Construction Project. Retrieved from AIDDATA; A Research Lab at William & Mary: |

|

|

Amnesty International (2020). Central African Republic: Chinese mining companies have moved on but need for investigation, accountability and remedy remain. Retrieved from Amnesty International: View |

|

|

Bennett A (2008). Process Tracing: A Bayesian Perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology. Oxford University Press. Pp. 702-721. |

|

|

Bowen GA (2009). Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qualitative Research Journal 9(2):27-40. |

|

|

Bushuev M, Topona E (2021). Russian mercenaries accused of human right violations in Central African Republic 2021. Accessed on 18 April, 2021. |

|

|

Carpintero Ó, Murray I, Bellver J (2016). The New Scramble for Africa: BRICS Strategies in a Multipolar World. In Analytical gains of geopolitical economy. Emerald Group Publishing Limited. |

|

|

CIDCA (2020). China donates anti-pandemic supplies to Central African Republic to help fight COVID-19. Retrieved from CIDCA: China International Development Cooperation Agency: |

|

|

Collier D (2011). Understanding Process Tracing. PS: Political Science and Politics 44(4):823-830. |

|

|

DeBoom M (2021). African countries are helping China go green. That may have a downside for Africans. Retrieved from The Washington Post: |

|

|

Dukhan N (2017). Splintered warfare: Alliances, affiliations, and agendas of armed factions and politico-military groups in the Central African Republic. Enough Project. |

|

|

Dukhan N (2018). Splintered Warfare II. The Enough Project. |

|

|

Dukhan N (2020). Central African Republic: Ground Zero for Russian Influence in Central Africa P 6. |

|

|

Eberechi I (2009). Armed Conflicts in Africa and Western Complicity: A Disincentive for African Union's Cooperation with the ICC. African Journal of Legal Studies 3(1):53-76. |

|

|

Energy A (2021). Central African Republic: Construction to begin on 25MW solar-battery plant. African Energy. |

|

|

Etahoben CB. (2021). Chinese And Russians Clash At Mining Sites In Central African Republic. HumAngle: |

|

|

Foster V, Butterfield W, Chen C (2009). Building Bridges; China's Growing Role as Infrastructure Financier for Africa. Retrieved from World Bank Ground eLibrary: |

|

|

Gathara P (2019). Russia has joined the 'scramble' for Africa. Al Jazeera. |

|

|

Goodison K (2019). Russia in the Central African Republic: Exploitation Under the Guise of Intervention. Philologia. |

|

|

Goodrick D (2019). Comparative Case Studies. In S. D. Paul Atkinson (Ed.). London: SAGE Publications Limited. |

|

|

Harding L, Burke J (2019). Leaked documents reveal Russian effort to exert influence in Africa. The Guardian. |

|

|

Harms R (2019). What a new scramble could mean for Africans. The Washington Post. |

|

|

Sadden J, Wasser B, Connable B, Grand-Clement S (2017). Russian Strategy in the Middle East. |

|

|

Minney L, Sullivan R, Vandenbrink R (2019). Amid the Central African Republic's search for peace, Russia steps in. Is China next? United States Institute of Peace: |

|

|

Munroe T, Osborn A, Pamuk H (2022). China, Russia partner up against West at Olympics summit. Reuters. |

|

|

IRIN News I (2004). China loans Bangui another US $2 million. The New Humanitarian. |

|

|

Ngounou B (2019). CAR: Parliament accuses 4 Chinese mining companies of ecological disaster. Afrik21. |

|

|

Opali O (2021). Belt and Road cooperation reaches heart of Africa. China Daily. |

|

|

Patey L, Olander E (2021). What's at stake for China in Sudan? Danish Institute for International Studies: |

|

|

Poplak R (2016). The new scramble for Africa: how China became the partner of choice. The Guardian. |

|

|

Radin A, Scobell A, Treyger E, Williams JD, Ma L, Shatz HJ, Zeigler SM, Han E, Reach C (2021). China-Russia Cooperation: Determining Factors, Future Trajectories, Implications for the United States. RAND CORP SANTA MONICA CA. |

|

|

Ramani S (2021). Russia strategy in the Central African Republic. (last accessed 30 April 2022). Available at: |

|

|

Republic E. o. (2019). Celebrating the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China and the unveiling ceremony of the China-China-Africa Friendship Village was held in the ancient village of Gailing in China. Retrieved from Embassy of the People's Republic of China in the Central African Republic: |

|

|

Republic P. o. (2016). Midterm report of the Panel of Experts on the Central African Republic extended pursuant to Security Council resolution 2262 (2016). United Nations Security Council. |

|

|

Rotberg RI (Ed.) (2009). China into Africa: Trade, aid, and influence. Brookings Institution Press. |

|

|

Salomone R (2022). The New Scramble for Africa. In The Palgrave Handbook of Africa and the Changing Global Order (pp. 309-322). Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. |

|

|

Snr MC (2021, December 30). In the new 'Scramble for Africa', nations have much to gain - but they can't ignore the risks. South China Morning Post. |

|

|

Spivak V (2019). Russia and China in Africa: Allies or Rivals? Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. |

|

|

Takouleu JM (2018, September 7). Central African Republic: China Gezhouba to rehabilitate Boali II hydroelectric plant. Afrik 21: |

|

|

WikiLeaks (2016, February 5). The New Dirty War for Africa's uranium and mineral rights. Retrieved from WikiLeaks: |

|

|

Witness G (2015). Blood Timber. Global Witness. |

|

|

Zhang X, Wasserman H, Mano W (Eds.) (2016). China's media and soft power in Africa: promotion and perceptions. Springer. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0