ABSTRACT

Across Africa, as in Ghana, state funding of political parties continues to generate debates across academic and policy circles. Against this background, three constituencies in the Upper West Region of Ghana were selected purposely to interrogate views of the public on this development. A combined 78 participants were selected in a mixed study design through purposive and quota sampling techniques. Primary data were gathered through focus group discussions and interviews revealed that 72.2% of the respondents favoured direct state funding of political parties indicating this will make multi-party democracy vibrant and competitive. 44.2% favoured full-state funding, whilst 32.7% proposed state-private partnership funding. 27.8% however, disapproved with state funding of political parties arguing that Ghana is already burdened with poor health systems, lack of quality education and unemployment. The study further revealed that the political parties’ programmes and activities proposed to be financed by the state principally include training of party agents, candidates and leaders (42.3%).

Key words: Political parties, democracy, state funding, constitution, consolidation.

Debates on funding of political parties continue to attract attention both within academic and policy circles, especially in Africa and other developing countries where democratic systems are being consolidated. Political parties finance essentially involves legal and illegal, as well as public and private financing of electoral campaigns and other political parties’ activities (Falguera et al., 2014; Magolowondo et al., 2012). According to Fernando and Biezen (2017), political parties’ funding could be a direct- situation where parties are granted access to state subsidies, or indirect financing – which includes; free access to the media (television and radio in most cases), training of party officials, tax exemption and access to state owned public spaces. Fernando and Biezen (2017) noted that in some countries in Europe and Latin America, political parties and or candidates are given financial assistance. Magolowondo et al. (2012) wrote that money lubricates the activities of political parties. They also expressed that availability and accessibility to state premises, media or vehicles by political parties enhances their internal structures. In their view, in some instances, the availability or lack of financial resource can decide whether a party may win or lose elections even well before they are conducted. Earlier, Kuenzi and Lambright (2005) wrote that, lack of funding weakens democratic institutions and the electoral process of a country.

Apparently, in Africa, most political parties are poorly organised and unable to make any meaningful contribution to the democratic growth of the continent (Falguera et al., 2014) due to poor funding (Rakner et al., 2007). According to Ohman (2013) and Falguera et al. (2014), in some African countries, political parties in government seemingly, abuse their access to state resources including money, personnel, publicly owned media and other communication tools to ensure they stay in power. The emerging idea is that only few countries in Africa have introduced some innovative means of public funding of political parties. Such development facilitates the disruptive phenomenon of winner-takes-all politics. Political parties thus, predominantly rely on private funding sources, and electoral campaigns are largely funded through candidates other than political parties which often results in kickbacks (Falguera et al., 2014).

Oyi et al. (2014) indicated that, the 1999 Constitution of Nigeria for instance, has provision for political parties funding and in some instances, parties have been assisted financially by the state. They however, expressed that in practice not so much has been done by the state. Oyi et al. (2014) hinted that parties have been relying on private and other sources of funding including; subscriptions, fees and levies from party membership, proceeds from parties’ investments, subventions and donations, among others, for the purpose of survival. This according to them, and in the absence of any effective regulation of the amount of private funding, has given rise to a situation where an individual or group finances parties and influences their course of operation. They concluded that most parties in Nigeria have become means for few political financiers to dictate the mode of awarding public works and procurement contracts.

Falguera et al. (2014) has stated that about 69% of African countries (through various modes of disbursement), provide public funding to political parties. They cited South Africa, Tanzania, and Zimbabwe among others as some of the countries where political parties benefit from public funding. Interestingly, these authorities wrote that some of the more stable African democracies including Ghana and Botswana have not implemented the call for public funding of political parties. Salih and Nordlund (2007) noted that the mode of disbursement of public funds to political parties and candidates differ from one country to another as manifested in Tanzania, South Africa and Mozambique among others.

They noted that in Tanzania for instance, each presidential candidate receives $9600 US Dollars.

Additionally, $1900 US Dollars is provided per constituency as a subsidy for campaign costs, together with another $1,900 US Dollars for each constituency won by party towards administrative costs. They wrote that in South Africa, one-third of total amount is given to presidential and parliamentary candidates. Salih and Nordlund (2007) indicated that in Europe as in the case of Germany, state subsidies to political parties are the main sources of political parties funding. These authorities expressed that in Netherlands, United Kingdom and America however, private sources remain the predominant income for political parties. It could be said that the disbursement model of some of the Europeans countries has been used as a blueprint for public funding of political parties by some African countries.

As in the case of Ghana, since independence in 1957, political parties have been relying on private funding including members’ contributions and donations from businesses (Magolowondo et al., 2012; Omari, 1970). However, these funds have been quite insignificant due to the level of poverty in the country. According to Centre for Democratic Development (CDD)-Ghana (2005a, b), this situation makes political parties inactive during inter-election periods and is unable to establish and maintain offices in many parts of the country. Although the Electoral Commission of Ghana supports political parties by granting them equal access to the state-owned media and limited number of vehicles during election seasons (1992 Constitution, Article 55, Clause 11-12), these forms of assistance are by no means inadequate. Lack of transparency and accountability frameworks and weak internal organisation have been cited as among the major challenges which restrain political parties from mobilising the needed financial resources to support their activities in in the country (Sakyi et al., 2015). Given this development, CDD-Ghana (2005) hinted that political parties are funded by few financiers who nonetheless control their decision- making processes which consequently undermines the principle of democracy. The general understanding is that the traditional role of political parties as “watch-dogs” of the state has been eroded. This probably could explain Gyampo’s (2015) assertion that parties are the most neglected and least funded institutions as in Ghana, with the worse affected been the parties in opposition (CDD-Ghana, 2005). This has further fuelled the debates on state funding of political parties in the country.

The debates on party financing for the development of a vibrant multiparty (constitutional) democracy in Ghana, a type of democratic arrangement where rules and regulations are institutionally set to check the behaviours of legislative, judiciary, executive and governmental powers (Oquaye, 2004), predates Ghana’s independence. According to Omari (1970), these debates date back to 1954 where the Cocoa Purchasing Company (CPC), a subsidiary of the Cocoa Marketing Board (CMB) established in 1952, allegedly was said to have secretly financed the CPP in the 1954 elections. The emerging theme is that there are some political experts, who make a strong case either for or against state funding (Sakyi et al., 2015).

CDD - Ghana (2005) noted that there are competing ideas on state funding of parties. It reported that some Ghanaians oppose the funding of political parties on the grounds that the country is not financially sound and struggles to meet the financial needs of some critical sectors such as the health, education and energy. Critics also contend that state funding of political parties may breed mushroom parties some of which actually cannot contribute to the nation’s democratic development but will only be targeting state funds. Gyampo (2015) wrote that governments are not willingly to fund political parties. His view was that politicians have to strive to reduce the perception of corruption against them and encourage their members to support them financially through the payment of monthly dues and special levies. He concluded that anything short of this will make political parties to continue function as weak election machines in Ghana. Others equally argue that if the state funds political parties, they will no longer feel a need in canvassing for funds from the public which forms part of their core activities (Baidoo, 2008). Similarly, there are those who think that the increasing dependence of parties on state funding makes them ‘lose their societal roots’ (Poguntke, 2002; van Biezen and Kopecky, 2014).

Contrarily, those who support state funding of parties express that political parties are integral part of the democratic process and governance (Van Biezen, 2004), and should be funded by the state. These advocates believe that since there is funding for various constitutional bodies in the country such as the EC, Judicial Service, Executive and the Legislature which promote democratic development and consolidation, political parties being the major stakeholders, especially in elections, should equally be funded. As noted by Gyampo (2015), the development and maintenance of extensive party structures by political parties for continuity and survival, as well as the increased use of consultants and public relation agencies in elections, have made the activities of political parties increasingly expensive in contemporary times. Westminster Foundation for Democracy WFD/CDD-Ghana (undated) noted that (multi-party) elections are costly for parliamentary contestants in Ghana. It indicated that the cost of running for political office increased by 59% between 2012 and 2016. It noted that on average, parliamentary candidates had to raise GH?389,803 or approximately US$85,000 in order to compete elections in their constituencies. Westminster Foundation for Democracy/CDD-Ghana (undated) concluded that given the high cost of politics in Ghana, the danger is that it may become the preserve of the elite and wealthy. Consequently, Parliamentarians will be pre-occupied with recovering their own investment rather than serving the populace. To this effect, there are those who opine that political parties should be supported financially to ensure equality of political competiveness as a wheel to consolidate the democratic gains in the country. Others are of the view that, Ghana with its image as a strong emerging democratic giant in Africa should be able to fund its political parties as done by countries including Tanzania, Uganda, and Zambia among others (Yeboah, 2009). Saffu (2003) concluded by saying that money promotes political competitiveness, multi-party democracy, and governance. It is in this regard that Stanbury (1986:795) earlier conceived money as ‘the mother’s milk of politics’.

Carothers (2006) opined that democracy cannot function without political parties. The question then is, ‘if constitutional democracy has been embraced as the basic philosophy for organizing the government and promoting peace and development in Ghana, why has the issue of state funding of parties not given a definitive response? The democratic growth of Ghana is evident by the growth of parliamentary seats from 192 in 1992 to 275 in 2016 (EC Ghana, 2017).

According to Boafo-Arthur (2003), Saffu (2003) and Ayee et al. (2007) among others, given the limited financial support from party supporters, public funding remains the possible option for political parties in the country. Apparently, scholarly works on the mode of party financing and its consequences, the activities that needs to be financed and the preferred body envisaged in managing funds earmarked for political parties are still quite limited in the Ghanaian context. This study would give much insight into the on- going debate on the subject and will help stakeholders to fashion out policies that will consolidate the democratic gains in the country. Probing into the problem at stake, this paper is guided by the following overriding questions:

(1) What political parties funding sources are known to the people?

(2) How would financing of political parties by the state impact the Ghanaian society?

(3) What political parties’ activities and programmes should be funded by the state and by what mode?

(4) What benchmark should be satisfied before a given political party could benefit from state funding?

(5)Which overseeing body is preferred to manage state funds envisaged for political parties?

Political parties and democratic consolidation

Political parties are free associations of persons that strive for power through the electoral process. By this means, they seek to control or influence the actions of government (Section 33 of the Political Parties Law, Act 2000 (Act 574). They participate in electoral campaigns, educational outreach and protest actions. Political parties often espouse an express ideology or vision bolstered by a written constitution with specific goals, forming a coalition among disparate interests (Bagah, 2011). It is in this regard that Randall and Svasand (2002) describe political parties as teachers of civic education. Political parties in this sense are different from pressure groups in that, whilst pressure groups seek for the interest of their members, political parties seek political office or power.

Like any other associations, political parties have a constitution, membership rules and, usually agreed policy for their members. Those who disagree may be expelled or may resign. In countries practising multi-party democracy where there is no legal restrictions as to the number of parties that are permitted to exist, the role of political parties in consolidating democracy is immense. They nominate some of their members for elections and campaign for them. In other words, political parties principally are instruments for contesting elections to exercise political power. Thus, they organize and encourage people to participate in elections and in other political activities such as political education, political campaigns or rallies and political socialization.

Generally, as political parties recruit widely, they often serve as agents of national integration. Their membership often cut across ethnic, class and religious groups. In some countries such as Ghana, ethnic or religious parties are not allowed to operate. The 1992 Constitution of Ghana for instance, demands that, a political party in the country needed to have a national character before it could be allowed to register and operate. This means that political parties should have branches in most parts of the country with membership from all ethnic groups and regions. A party’s motto or emblem cannot have ethnic, religious or tribal connotations (Article 55 (4), 1992 Constitution of Ghana). The rationale for all these is to make political parties a tool to unite people of diverse backgrounds to forge national unity. Nonetheless, all their activities require substantial funding.

The preceding discussions highlight the impetus for funding political parties. Falguera et al. (2014) however, have cautioned that whilst money is required for the growth and development of multi-party democracy, it can also negatively influence the political process and decision through the buying of votes. Whitehead (2002) earlier expressed that due to the expensive nature of political campaigns, elections themselves could be a source of corruption. He contends that politicians often seek to raise funds or win votes in various illicit ways such as the control of the procurement process by the government. The implication is that funding of political parties has to be well managed and monitored to avoid abuse. As voiced by Ohman (2013), the nature of politics varies significantly between different regions and countries. He however, admits that in all parts of the world, money matters in a political decision making process. He contends that credible and genuine elections and electoral campaigns demand management of political finance. He noted that defective management of political finance has the potential to skew competition between contestants.

The foregoing debates underscore the relevance of Ferguson’s (1983) Investment Theory of Political Parties which underpinned the study. The Theory recognizes the critical role money (investment) play in party politics. It posits that business elites play instrumental role in political systems. The thrust of the Theory is that money influences politics and this is due to the cost of acquisition of information. The Theory was in reaction to the Voter Realignment Theory which envisaged voters to play a leading role in political discourses. The Theory maintains that where few wealthy individuals invest in political parties, they dominate the political system and influence the state and the course of governance. Ferguson (1995) therefore suggests innovative ways of funding political parties to avoid manipulation of the political system by the well-off investors. He proposes that the costs of financing political parties should be subsidised by the state either by providing staff to politicians or franking mail among others.

The relevance and implication of Ferguson’s (1983) Investment Theory of Political Parties to the recent study is that political parties cannot exclusively be funded by the state; neither could the responsibility of financing be borne solely by individual voters or citizens. What this suggests is that funding of political parties should be seen as a shared responsibility involving the state, cooperate bodies and voters or individuals. Constitutional democracy, championing by political parties as in Ghana and promoting broad-based human development demands a critical analysis of their growth in terms of financing of their activities and programmes as espoused by Falguera et al. (2014). In the view of Bohman (2004), democracy demands much of its citizens and thereby raises the standard of political legitimacy. Democracy thus, facilitates collective public decision-making for the mutual benefit of the populace.

Study locality

The study locality is the Upper West Region of Ghana. The Region covers a geographical landmass of approximately 18,476 square km. This is about 12.7% of the total landmass of Ghana. It shares political boundary with the Republic of Burkina Faso to the East, Upper East Region to the east and Northern Region to the south. The Region has 11 administrative Districts namely; Wa Municipal, Wa East, Wa West, Nadowli-Kaleo, Dafiama-Busie-Issa, Jirapa Municipal, Lambussie, Lawra Municipal, Nandom, Sissala East and Sissala West District Assemblies. The Region currently has the same 11 political parliamentary constituencies namely; Wa Central, Wa East, Wa West, Nadowli-Nadowli, Jirapa, Lambussie-Karni, Lawra, Nandom, Sissala East and Sissala West (Ghana Statistical Service, 2012). The Upper West Region was chosen because it fits into the two main variables of the study. These are vibrant activities of registered political parties and poverty level of the electorate of the Region. This poverty phenomenon has an impact on party members/sympathizers in contributing towards the financing of their respective political parties.

This study limits itself specifically to three Constituencies namely Wa Central, Nadowli-Kaleo and Sissala East. The three Constituencies were purposely selected based on their peculiarity in terms of having both party office (functional party office) and party executives (functional executives) (Upper West Regional Electoral Commission, 2018). They therefore have party structures for easy access to information. Besides, their locations in the Region represent the three major ethnic groups, that is, Dagabas, Waalas and Sissalas. Such selection ensured diversity in the views of respondents.

Wa Central Constituency

The Wa Central Constituency was chosen as one of the study area because of its vibrant political activities in the Region. Wa Central with Wa as the Regional Capital is strategic, in that it has more infrastructure, large population and seasoned politicians including the Regional Minister. The various political parties within the constituency with both party office and party executives are; the New Patriotic Party (NPP), National Democratic Congress, CPP, People’s National Convention (PNC) and Progressive People’s Party (PPP). The other political parties in the constituency without party office but with party executives are Great Consolidated Popular Party (GCPP) and National Democratic Party (NDP) (Upper West Regional Electoral Commission 2018).

Nadowli-Kaleo Constituency

Nadowli-Kaleo Constituency is known for its political party programmes and activities. This constituency was purposely selected because the settlements in the constituency are basically the rural type. Whilst the rural settlements are basically agrarian, the urban settlements are commercially oriented with emphasis on income-generating activities. The views of different classes of society related to the topic were considered important. Apart from its political programmes, it is one of the three constituencies in the Region that has both party office and party executives (Upper West Regional Electoral Commission 2018). The political parties within the constituency that have both party office and party executives are the NPP, NDC and PNC. CPP is the other political party in the constituency without party office but with party executives.

Sissala East Constituency

Sissal East Constituency has Tumu as its Capital. It was chosen as a study area because of two main reasons. Firstly, apart from being one of the oldest Constituencies in the Region, it is also considered as the smallest constituency in the region, but has four active registered political parties whose programmes and activities could be relied on for some information. More so, it is a typical rural area with majority of the people engaged in subsistence farming and petty trading. Issues surrounding funding of political parties are considered critical in such Constituency. The political parties within the constituency that have both party office and party executives are the NPP, NDC and PNC. CPP is the other political party in the constituency without party office but with party executives.

Research design and selection of research participants

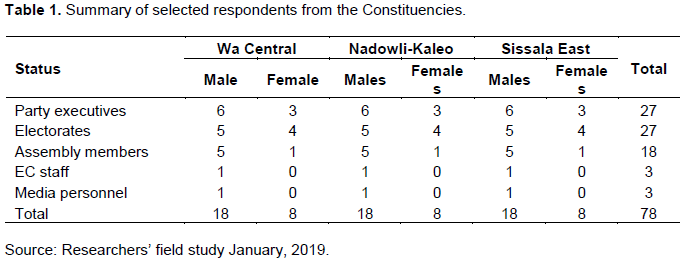

The research design adopted in this study was the mixed method design but inclined to qualitative as opposed to quantitative research. This enabled the researchers to have a wider perspective of the specific issues at stake as espoused by Bacho (2001). In all, 78 participants, comprising 72 respondents and six key informants were selected using quota sampling and purposive sampling techniques. In choosing the total respondents, the study areas were grouped into strata based on a single factor of proximity to electoral information. Purposive sampling technique was used in selecting 27 Political Parties’ Executives. In each of the three selected constituencies, the political party chairperson, one other male executive and the constituencies’ women organizer from each of the three selected vibrant political parties namely; NDC, NPP and PNC were selected. These categories of people were purposively selected because the researchers had the firm believe that they were in better position to provide vital information relating to the study. Besides, six key informants (three media personnel and three electoral commission staff) were also selected purposely.

Quota sampling technique was employed to select 27 electorates (nine each from the three study Constituencies). The researchers selected this category of respondents on the basis of two major principles namely; (1) being a registered voter (male or female) and (2) ordinary resident in the constituency for at least six months which is in line with the electoral commission’s requirement. Those who rightly fit into the requirements of the criteria and willing were selected for the study. This method was adopted due to the fact that it was difficult to randomly select the respondents. In the view of Sarantakos (2005), quota sampling is used when it is difficult to approach the respondents in any other systematic way. Quota sampling technique was equally used to select 18 Assembly Members (six each from the three study Constituencies). The quota sampling technique adopted was therefore considered appropriate for the selection of the 27 electorates and the 18 Assembly Members. The similar information given during the data collection process was an indication that the views of any other respondents would have been insignificant. The study thus made use of a combined sample size of 78 as depicted by Table 1.

Methods of data collection and analysis

Primary data were gathered through face-to-face interview and focus group discussions. Each of these methods has its own strength and weakness. They were therefore carefully selected to complement one another. Besides, these methods were utilized with the view to minimize cost, reduce problems relating to retrieval, and to ensure a high level of participation and response rate.

Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) were held with the Political Parties’ Executives. Political Parties’ Executives play instrumental role in terms of building strong party structures at the grass root. Their views on state funding of political parties were laudable. One focus group discussion each was held in the three Constituencies with each focus group having nine discussants. Three participants came from each of the three selected political parties. In this way, information was obtained from people with different political orientations. A discussion guide was designed based on the objectives of the study. Twumasi (2001) is of the view that FGD technique affords respondents the power to express themselves in a discussion group. This method enabled the researchers to access the discussants viewpoints, perceptions and differences. The technique allowed the researchers to gather validated data from the standpoints of the various political parties. The arguments and counter arguments from the respondents also helped in weeding out any irrelevant and unsubstantiated information.

In this study, a-face-to-face interview with the aid of questionnaires was used to obtain information from the Assembly members and Electorates from the three selected Constituencies. Three field assistants were employed, trained and supervised to assist in the administration of the questionnaires. This technique was also employed in gathering relevant information from the key informants. In all situations, the researchers notified the respondents a day or two prior to the interviews. In order to avoid disappointments, different dates and times were arranged to meet the respondents in each community. The field study was conducted between November, 2017 and January, 2018. A follow up study was however, conducted in August, 2019 in the selected constituencies. Information gathered was that the parties’ structures remain unchanged except the executive portfolios of some of the parties.

Quantitative data were analyzed using basic statistical tools and techniques. Frequency tables, percentages, graphs and charts were used in presenting the information. Qualitative data on the other hand, were analysed descriptively by playing out the voices of the respondents. Data from interviews and focus group discussions conducted with all the respondents were transcribed, carefully edited and analysed manually by making summaries of their views and categorized into themes. On ethical grounds, the names of the respondents and their characteristics were not disclosed in this study.

The discussions were done around five thematic areas namely; socio-demographic characteristics of respondents, sources of political parties funding, perspectives on party financing, the nature of parties programmes and activities that should be funded by the state, and how state funding should be managed.

Biographic information

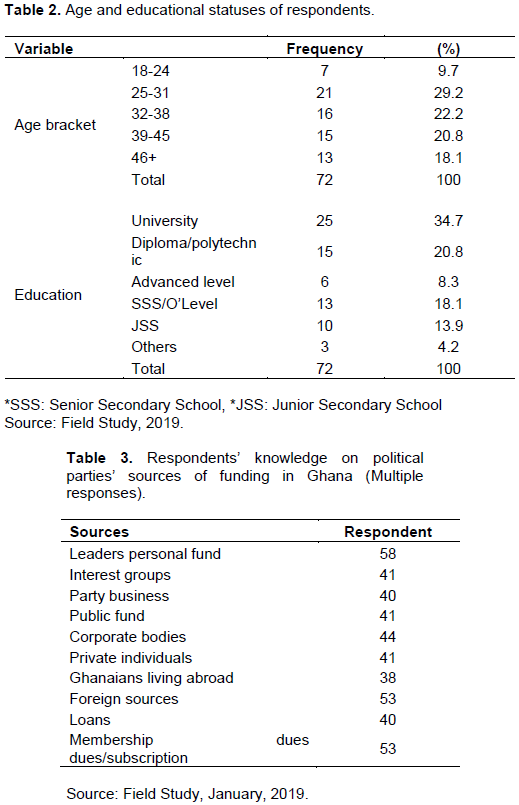

Age and educational statuses of respondents

With the focus of the study being on election issues, it was prudent to choose respondents who were of the legal age of qualified voters. Thus 18 years and above. This was to ensure that respondents had at least a fair idea of the political system in the country. Hence, those within the legal voting age were reliable source of data gathering for the study. Out of the 72 respondents, 29.2% fell within the age range of 25 and 31 years with only 9.7% falling within the age bracket of 18 and 24 years. About 20.8% fell within the ages of 39 and 45, those between the ages of 32 and 38 years were 22.2% with the remaining 18.1% being 46 years and over. None of the key informants was below thirty years. Whilst two fell within 32-38 years, the remaining four fell within that of 39-45 years. Thus, the views of all respondents from the various age brackets were considered.

A study involving financial issues, economic and political analysis requires respondents of some high level of education. The study thus sought to find out the educational status of the respondents. It was established that majority (34.7%) of the respondents had University Education, 20.8% had Diploma/Polytechnic Education whilst 8.3% had Advance Level (A/Level) background. Another 18.1% had Senior High Education/Ordinary Level and 13.9% had Junior High School/Basic Education. Respondents with other forms of education, that is, Arabic studies and traditional studies among others that are not classified under formal education were 4.2%. Table 2 presents, the results on the respondents’ age and education.

All the key informants had University Education. The results showed that selected respondents at least had some form of education which could reflect in their understanding and response to the research questions.

Objective one: Respondents’ awareness of sources of funding of political parties

People’s knowledge about the level of political parties’ financial muscles has an implication on how they would respond to their call for financial and logistics assistance. In this regard the study sought to examine the respondents’ awareness of the sources of political parties’ funding. Various sources of funding were cited by the respondents with the key sources being; leaders’ personal fund (58/72), membership dues/subscription (53/72) and foreign sources (53/72). These findings support Saffu’s (2003) assertion that the main sources of income to political parties are seed money from founding members, membership dues, donations as well as local fund-raising activities.

Table 3 shows that the respondents have a fair knowledge of the several funding sources available to political parties in Ghana. If this is the situation all over the study region, then it could be said that the political communication/education on sources of political parties funding has been quite encouraging. Probing further as to the sources of their level of awareness and knowledge on the sources of funding for political parties, 73.6% (53) of the entire respondents attributed their sources of information to internal party meetings/fora, 25.0% linked their awareness to public debates on the mass media especially on radio, whilst 1.4% attributed their source of information to informal interaction/rumour. The informants from the media fraternity supported the points made by the respondents. One of them remarked:

‘The media contributes to the improvement of the democracy in Ghana by way of offering their medium as a platform for public debates and source of timely and relevant information to the citizens. This shows how the media can be instrumental in the democratic development of Ghana through the dissemination of information’ (A key Informant Interview, 2019).

The role played by the media in creating awareness of the masses of the sources of funding of political parties as gathered, buttresses Norris’ (2004) view that, political communication involves the transmission of information among politicians, the news media and the public. In all the three focus group discussions held in the three constituencies, regardless of the political backgrounds of the discussants, the picture that emerged was that financing constituted a major hindrance to the running of political parties’ activities and programs. It also emerged that in response to financial challenges, some party executives in some situations have to use their own resources in organising meetings due to inadequate funding. This is what Loyal (pseudonym) said in a FGD held in Nadowli-Kaleo in November, 2018:

‘Inadequate sources of funding tend to compel political parties to adopt various strategies of sourcing funds for their activities and programmes, which they will have to pay back in cash or kind when they gain political power leading to corruption and kickbacks and appointment of incompetent people to hold public positions’.

This issue of inadequate funding was echoed by the key informants. This is what one official stated:

‘Multi-party democracy can best develop when there is stiff competition in the political climate and this can only be achieved if political parties, especially the smaller parties can be empowered financially by the state to play the role expected of them’ (Key Informant Interview, January, 2019).

The opinion of the key informants supports the view of Bekoe, when in a Consultative forum organized by the Electoral Commission Consultative Report (2003), he stressed that, political parties needed financial support to grow as organized institutions to enrich the practice of good governance in Ghana. He however, cautioned that the burden of financing should not be seen as a government prerogative, and entreated Ghanaians to assist in this regard.

Objective two: Argument for and against funding of political parties

The study sought the views of the respondents on the funding of political parties. Fifty-two respondents (72.2%) indicated that political parties should be funded by the state by proving them with cash, logistics and tax exemption. On the contrary, 20/72 respondents representing 27.8% however, disagreed with the suggestion of state funding of political parties. Their main argument was that political parties are like any other business organizations and should be funded by members as such. More so, they argued that Ghana is already burdened with a number of problems including poor health facilities (16/20), poor quality of education (15/20) and unemployment (20/20). These respondents were of the view that such a move will worsen the already economic misfortunes of the country. This is what a respondent remarked in an interview:

‘If Ghana were to be America or UK, I will not be troubled with the issue of state funding of political parties. Look! The country is having a serious unemployment situation.

As a University graduate, I have struggled in vain for the past four years to get a job. Why should the state use public limited funds to support political parties that have shown very limited commitments to the electorates once they assume political power? I completely disagree with such a proposal’.

The opposing views on state funding, as gathered, confirm Sakyi et al. (2015) work which showed that Ghanaians have conflicting ideas about the funding of political parties by the state. Their conclusion however that was the elite political class and party executives have much preference for public funding as opposed to the ordinary party members. In this study, an aggregate of 48 respondents constituting about 66.7% who could loosely be described as elites had University, Diploma or Advanced Level (A ‘Level) education. This probably could explain why 52/72 respondents favoured state funding of parties.

Those who favoured state funding of political parties (52/72) were of the view that the country stands to gain by such political arrangement. Twenty-one out of the 52 respondents said that state funding of political parties activities and programmes will help prevent political corruption especially among the ruling party. According to these respondents, when political parties are funded by individuals and collective groups, they tend to influence political decision in their favour. Such persons win contracts and political appointments even if they lack the necessary qualification and competence. This opinion of the respondents confirms Saffu’s (2003) assertion that, when political parties are relied on membership dues, seed money and donations among others, what he termed as traditional funding methods, it mostly breeds corruption with the results being that the richest survives or wins not the qualified candidate. As espoused by Ferguson (1983) Investment Theory of Political Parties, when the well-to-do individuals predominantly invest in the political system, the tendency for them to manipulate the state and the course of governance is very high. His proposition to the problem was that the costs of financing political parties should be subsidized by the state through varying forms including provision of staff to politicians.

Forty-four (44/52) respondents asserted that funding of political parties by the state will help strengthening parties’ structures and promote keen and fair electoral competition in the political climate and the over-all peace of Ghana. The respondents were of the view that inputs made by the various political parties will help challenge the political system in terms of policies and delivery. The respondents further argued that, when political parties are funded by the state, smaller political parties may have the opportunity to develop to prevent the growth of either one-party state or two-party system of government. The masses will then have the opportunity to select qualified and competent candidates from the lot to fill public offices. This view buttresses Windsor’s (2007) assertion when he indicated that democracy is about electoral processes and all that is necessary for elections to be fair and meaningful; free association, free speech, and an independent and professional news media. This competition could be considered productive for the growth of the country’s democracy.

Prevention of the establishment of mushroom political parties was recorded as the least influence of state funding on political parties activities and programmers accounting for 7.7% (4/52). According to the respondents, if the state funds political parties, it will help prevent the establishment of mushroom political parties. The respondents were of the view that given the fact that political parties have to satisfy certain conditions before they can benefit from the state funding, such conditions will help prevent the establishment of political parties which cannot make any impact on the country’s multi-party democracy in the first instance.

In furtherance, Twenty-three (23/52) respondents representing 44.2% were in support of fully state funding, 32.7% were of the view that there should be state-private partnership, whilst further 23.1% had no idea as to the form the state funding should take. The emerging idea is that the state alone cannot fund political parties. The findings are theoretically consistent with Ferguson (1983) Investment Theory of Political Parties which sought to promote and regulate the political system through mutual cost sharing by the state, voters/citizens, political parties and other cooperate bodies. The prevailing information indicates that whilst the state has a role to play towards the growth and survival of political parties and multi-party democracy, other actors similarly cannot be neglected in matters of political parties financing.

Objective three: Political parties’ activities and programmes that need to be funded

Asked as to which political parties’ activities and programmes should be funded by the state, the respondents answers were in agreement with the study of Salih and Nordlund (2007), as majority (22/52) were of the view that state funds for political parties should prioritize the training of party personnel such as pooling agents, candidates and party leaders. Four (7.7%) supported the idea of using the fund to sponsor political party candidates in general elections; 17.3% were of the view that state funding should support election campaigns of political parties whist 11.5% suggested support for political party organisation in terms of administration and management. Further 11.5% were in support of using state fund for infrastructural development of political parties. Another 9.6% of respondents were of the view that the fund should be used to organize constituency primaries for political parties.

These findings are theoretically consistent with the Investment Theory of Political Parties which construes democracy as an institution which demands much of its citizens and thereby raises the standard of political legitimacy. The findings also suggest that there are a number of political parties’ activities that could be supported by state funds. However, the dominant area that needs much state funding as identified in the results of this study is the training of party personnel including pooling agents, candidates and party leaders. Any policy intervention into state funding of political parties should primarily target the development of manpower as human capital, is essentially the beginning of every meaningful development.

Objective four: Benchmark for accessing state funds

One major objective of the study was to ascertain from the respondents the conditions that political parties have to satisfy before they could befit from state funds. This objective was influenced by the EC of Ghana’s bench mark which sought to include and exclude political parties from funding support. Majority of the respondents (24/52) representing 46.2% were of the opinion that state funding should be available to political parties that obtained of and above 5% of total votes cast during previous presidential and parliamentary elections (Table 4). The respondents who supported this prerequisite argue that only political parties that make an impact on general elections (presidential and parliamentary) should be acknowledged by way of supporting their activities and programs. The analysis of the prerequisites implies that not every political party will equally benefit from the political parties’ fund. This understanding however, may defeat the idea of supporting political parties to ensure equality of political competiveness.

In response to the question whether independent presidential and parliamentary candidates should have access to the state funding, majority of the respondents (32/52) representing (61.5%) were against the idea. The main concern of the respondents who opposed independent candidates benefiting from the fund was that it may lead to distortions and corruption in our multi-party democracy. In a FGD at Wa Central in January, 2019, this is what Mr K expressed:

‘Corrupt personalities may set up political parties to just benefit from the fund, even though they know they do not stand any chance of winning or making an impact on elections’.

Only 38.5% supported the idea. Those who supported the idea indicated that once a party is fully registered, it should be benefited from any funding from the state. In finding out as to when the state should make available funds for political parties, 30/52 (57.7%) of the respondents were of the view that disbursement of the fund should be made only during electioneering year, 25.0% supports disbursement made immediately after general elections, 1.9, 7.7 and 7.7% of respondents were of the view that disbursement of the fund should be made annually, half-yearly and quarterly (3 months) respectively.

Objective five: Management/supervision of state funds earmarked for parties in Ghana

As part of the objectives, the researchers sought the opinion of the respondents as to the body deemed necessary to manage or supervise funds earmarked by the state. This is necessary to ensure efficiency, timely and fair disbursement, among others so as to ensure sustainability of such important national policy. According to the respondents, an independent body or special political party fund secretariat is considered to be the right supervisory body to manage the fund to be established, receiving 36.5% approval (19 out of the 52 respondents). This could mean that political parties and the electorates may have their reservation about the integrity of Ghana’s Electoral Commission notwithstanding its constitutional mandate. The EC in this regard should prove to be a true neutral arbiter in Ghana’s electoral system. The finding contradicts CDD-Ghana’s (2005) earlier study which showed that the Electoral Commission was the most preferred agency envisaged to manage state funds intended for political parties. The findings however, was in line with the work of Ayee et al. (2007) which showed that most people preferred the establishment of an independent body (35.1%) as opposed to the Electoral Commission (EC) (25.4%).

Twenty-five (25.0 %) approves the setting up of an independent parliamentary committee, 19.2% supports the EC of Ghana to supervise and manage the fund, and 11.5% approves National Commission for Civic Education to manage the fund whilst the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (CHRAJ) received 7.7% approval. Further 1.9% of respondents have no idea as to which institution should manage the fund.

This study has revealed that Ghana stands to gain enormously if political parties are resourced. The development of strong opposing political parties is necessary for a healthy competition in the Ghanaian political system. The changing nature of politics in present times which requires elaborate party structures and arrangements, means that parties cannot ran away from state support. Financing political parties’ programmes and activities by the state is conceived as a critical phenomenon as it may prevent incumbency advantage and its attendant corruption due to pressure of party financiers. However, given the socio-economic challenges such as; poor health facilities, poor quality education and unemployment which already confront the country as identified in the study, it is not clear whether the state could indeed commit itself fully to finance political parties.

The policy implication of the findings is that more awareness creation and broad-based consultations with the citizenry, political parties, the state and civil society organisations is required on the issue of party financing, growth, survival, and the democratic consolidation of the country. Besides, ground breaking ways of funding political parties including training of party officials, accountable private and cooperate donations from both domestic and foreign, as well as creation of political parties’ ‘fund’ should be exploited as espoused by Ferguson’s (1983) Investment Theory of Political Parties. This in effect will promote mutual and healthy cost sharing among various actors and the same time, boost the activities of political parties to enable them perform their traditional watchdog role of the state.

A workable regulatory framework implemented by an independent regulatory body is equally necessary as a country to check donor abuse (corruption), and also help promote fair political competition. This stemmed from the fact that lack of transparency, accountability and commitment to the populace has been a common problem leveled against political parties.

The implication is that political parties have to redeem their sinking image and attract the support of the masses by supporting anti-corrupt institutions such as the Auditor General and also demonstrate actual commitment to the public through formulation of visible, beneficial policies and programmes once they assume political power. Indirect funding through tax exemption on importation of all logistics meant for political parties’ activities should be broadly implemented. Such taxes can be retained and re-route to train political party agents, leaders and candidates to make them more functional. This however, calls for a strict monitoring or financial discipline to avoid the abuse of such tax retention by the individuals for their private gains.

The authors have not declared any conflicts of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Ayee JRA, Anebo F KG, Debrah E (2007). Financing Political Parties in Ghana. Report of the Consortium for Development Partnerships. pp. 1-44.

|

|

|

|

Bacho FZL (2001). Infrastructure delivery under poverty: Poverty water delivery through action in Northern Ghana. Spring Research Series 34. SPRING Centre: University of Dortmund.

|

|

|

|

|

Bagah AD (2011). A Speech Delivered on Political Parties at the 11TH Annual National Constitution Week Celebration Organised by The National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE) on 28th June, 2011 at In - Service Training Centre, Wa- Upper West Region.

|

|

|

|

|

Baidoo I (2008). A Debate on State Funding of Political Parties in Ghana: Copy. 2009 National Union of Ghanaian Students, Ghana.

|

|

|

|

|

Boafo-Arthur K (2003). Political Parties and Democratic Sustainability in Ghana, 1992-2000. In M.M.A, Salih (Ed.). African Political Parties: Evolution, Industrialization and Governance. London: Pluto Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Bohman J (2004). Realizing Deliberative Democracy as a Mode of Inquiry: Pragmatism, Social Facts, and Normative Theory. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 18(1):23-43.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Carothers T (2006). The Weakest Link: Aiding Political Parties in New Democracies. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

|

|

|

|

|

Centre for Democratic Development (CDD)-Ghana (2005a). Political Party Financing in Ghana: CDD- Ghana Research Paper N0. 13. Accra: North Airport Residential Area.

|

|

|

|

|

Centre for Democratic Development- Ghana. (2005b). Financing Political parties In Ghana. Policy Guidelines.

|

|

|

|

|

Electoral Commission (EC) of Ghana. (2017). Seat distribution in Parliament by Political Parties (1992-2016). Accra: EC.

|

|

|

|

|

Electoral Commission Consultative Report (2003). Financing Political Parties and the Electoral Process in Ghana. EC/KGC/USAID Collaboration: Prepared by KAB Governance Consult (KGC). Cantonments- Accra.

|

|

|

|

|

Falguera E, Jones S, Ohman M (2014). Funding of Political Parties and Election Campaigns: A Handbook on Political Finance (Eds.). Stockholm, Sweden. International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA).

|

|

|

|

|

Ferguson T (1983). Party Realignment and American Industrial Structure: The Investment Theory of Political Parties in Historical Perspective. Research in Political Economy 6:1-82.

|

|

|

|

|

Ferguson T (1995). Golden Rule: The Investment Theory of Party Competition and the Logic of Money-Driven Political Systems. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Fernando CB, van Biezen I (2017). The Regulation of Post-Communist Party Politics (Eds.). London: Routledge.

|

|

|

|

|

Ghana Statistical Service (GSS) (2012). 2010 Population and Housing Census Summary Report of Final Results. Accra: Sakoa Press Limited.

|

|

|

|

|

Gyampo REV (2015). Public Funding of Political Parties in Ghana: An Outmoded Conception? Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies 38(2):1-27.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kuenzi M, Lambright G (2005). Party Systems and Democratic Consolidation in Africa's Electoral Regimes. Party Politics 11(4):423-446.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Magolowondo A, Falguera E, Matsimbe Z (2012). Regulating Political Party Financing: Some insights from the praxis. Netherlands: The Netherlands Institute for Multiparty Democracy (NIMD)/ International IDEA.

|

|

|

|

|

Norris P (2004). Politics in Ghana (1982-1992). Accra, Ghana: Tornado Publications.

|

|

|

|

|

Ohman M (2013). Controlling Money in Politics: An Introduction. Washington, D.C: International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES).

|

|

|

|

|

Omari PT (1970). Kwame Nkrumah: The Anatomy of African Dictatorship. Accra: Moxon Paperback.

|

|

|

|

|

Oquaye M (2004). Politics in Ghana (1982-1992): Rawlings, Revolution and Populist Democracy. Osu- Accra: Ghana Tormado Publications.

|

|

|

|

|

Oyi RO, Okechukwu E, Nwoba HA (2014). Political Party Funding in Nigeria: A Case of Peoples Democratic Party. Nigerian Chapter of Arabian Journal of Business and Management Review 62(11):1-18.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Poguntke T (2002). Party organizational linkage: Parties without firm social roots? In Luther, Müller-Rommel, F. (Eds.). Political parties in the new Europe. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, pp. 43-62.

|

|

|

|

|

Rakner L, Menocal RM, Fritz V (2007). Democratisation's Third Wave and the Challenges of Democratic Deepening: Assessing International Democracy Assistance and Lessons Learned. London, UK: Overseas Development Institute.

|

|

|

|

|

Randall V, Svåsand L (2002). Introduction: The Contribution of Political Parties to Democracy and Democracy Consolidation. Democratization 9(3):1-10.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Saffu Y (2003). 'Funding of Political Parties and Elections Campaigns in Africa', In R. Austin and M. Tjermstrom (Eds.) Funding of Political Parties and Elections Campaigns. Sweden: IDEA, pp. 21-29.

|

|

|

|

|

Sakyi EK, Agomor KS, Appiah D (2015). Funding Political Parties in Ghana: Nature, Challenges and Implications. London: International Growth Centre (IGC).

|

|

|

|

|

Salih M, Nordlund PMA (2007). Funding Political parties in Emerging African Democracies: What Role for Norway? Updated in Famborn S, 'Public funding of political parties in Africa.

|

|

|

|

|

Sarantakos S (2005). Social Research (3rd ed). New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Stanbury WT (1986). "The mother's milk of politics: Political contributions to federal parties in Canada, 1974-1984". Canadian Journal of Political Science 19(4):795-821.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

The Political Parties Law, Act 2000 (574). Ghana: Electoral Commission of Ghana.

|

|

|

|

|

The Republic of Ghana Constitution (1992). Fourth Republic Constitution of Ghana. Tema: Ghana Publishing Company.

|

|

|

|

|

Twumasi PK (2001). Social Research in Rural Communities (2nd ed.). Accra: Universities Press. Upper West Regional Electoral Commission (2018). Wa, Ghana.

|

|

|

|

|

Van Biezen I (2004). 'Political parties as public utilities'. Party Politics 10 (6):701-722.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Van Biezen I, Kopecký P (2014). The cartel party and the state: Party-state linkages in European democracies. Party Politics 20:170-182.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Westminster Foundation for Democracy (WFD/CDD-Ghana. (Undated). The cost of Politics in Ghana. Available:

View. Accessed: 14th November, 2019.

|

|

|

|

|

Whitehead L (2002). Democratization: Theory and Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Windsor JL (2007). Breaking the Poverty-Insecurity Nexus: Is Democracy the Answer? In: Brainard, Lael, and Chollet, Derik, eds. Too Poor for Peace: Global Poverty, Conflict, and Security in the 21st Century. Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution Press, pp. 153-162.

|

|

|

|

|

Yeboah K (2009). Implement State Funding of Political Parties. Daily Graphic. Retrieved November 12, 2019, from

View.

|

|