ABSTRACT

While it can be argued that elections are not enough for the consolidation of democracy, elections are fast emerging as a significant component of democratization. Not least, because their regularity has enhanced freedom and liberalization, but also because they have been the cause and/or effect of democratic consolidation. As a key component of democracy, elections have become the barometer and template upon which other liberal democratic principles are institutionalised. The paper examines elections in Africa, using the recently concluded 2015 elections in Nigeria to show the significance and effect of credible elections to democratic consolidation by situating its argument within the context of Staffan Lindberg theoretical postulation. The paper adopts a qualitative analysis drawing data from PhD field work conducted in 2014. It also makes use of available texts from INEC document, elections observers’ reports, data from Freedom House and Polity scores and other documentary evidences to analyze the election. The study argues that, regularities of elections have potential for democratic improvement and that the 2015 elections have restored Nigeria back on the path of democratic consolidation through elite acceptance of electoral outcome, electoral turnover, elite pact and consensus, coordinated opposition and effective electoral management. It further suggests that more democratic reforms are required to ensure strengthening of the electoral process and institutions in the interest of democratic consolidation in Nigeria.

Key words: Elections, electoral turnover, democratization, democratic consolidation, Legitimacy.

A profound consensus has emerged that elections have come to be seen as significant menu of democratic consolidation in post-third wave democratisation in Africa (Schedler, 2002; Lindberg, 2006; Bogaards, 2007; Rakner et al., 2007; Moehler and Lindberg, 2009; Adebanwi and Obadare, 2011). Empirical evidence across democratising countries also shows that a number of countries such as Ghana, Senegal, South Africa, Botswana, Benin, and Cape Verde among others in the continent have progressed in their electoral democracy

[1]. The progress made is a reflection of the institutionalisation of peaceful democratic elections, electoral turnover and consolidating democracy. While it cannot be concluded that election is the only most fundamental principle of democracy, it spurs other liberal democratic principles by ‘creating incentives for political actors, fostering the expansion and deepening of democratic values’ (Lindberg, 2006: 74). As noted by Mozaffar elections have become the major cause of, ‘albeit sufficient sources of behavioural, attitudinal and legitimacy in Africa’s emerging democracy’. Through the attitudinal change, elections provide avenue for the expression of franchise, open opportunity for the leaders to be replaced and accept democratic outcome. Huntington (1991) noted that under this condition, election becomes ‘the death of dictatorship’.

As a life blood of democracy, elections enhance participation and restore confidence in political actors to believe that democracy is the acceptable system of government that promotes collective aspirations. The recently concluded 2015 general elections in Nigeria have once again shown the significance of elections to democratic stability. The 2015 general elections are indeed remarkable in the Nigeria’s democratic development. Not least because it marked for the first time that Nigeria successfully turned over power from the incumbent to the opposition party at the federal level in a less controversial and peaceful electoral process; it is the fifth consecutive election of a perverted electoral process which was expected to correct the backlash of previous electoral process that has challenged consolidation of democracy since 1999 in Nigeria.

While the apprehension resulting from the intense Boko Haram attacks and the growing public perception of the poor preparation and lack of confidence on INEC in conducting credible elections poses serious concern for the 2015 elections, the outcome of the election was however satisfactory to the broad spectrum of the major stakeholders. Both domestic and international election observers attest to the credibility and legitimacy of the election. In its report for example, the European Union Electoral Observation Mission (EUEOM) noted that the election day passed peacefully with appropriate performance by security agencies and EUEOM observers saw no evidence of systematic manipulations” (EU-EOM, 2015: 1).

Against this backdrop, this paper examines the significance of the 2015 elections to democratic consolidation in Nigeria. Using the recently concluded 2015 elections in Nigeria to show the prospect of credible elections to democratic consolidation, it situates its argument within the context of Staffan Lindberg theoretical postulation. According to Lindberg, there is an inherent value in the conduct of elections, even if they are characterized by imperfections; elections have potential for democratic development and consolidation (Lindberg, 2006). Following from the background which is the first part, a theoretical argument of election and democracy in Africa is advanced in the second part. In the third part, a critical interrogation and analysis of elections from 1999 to 2011 was undertaken to underline Nigeria’s push towards democratic consolidation. The fourth part highlights the 2015 election with a view to advancing the argument that elections have potential for democratic consolidation with the 2015 election which has brought about, for the first time, electoral turnover and power alternation from the incumbent to the opposition candidates. The study then concludes and offers recommendation as appropriate.

ELECTION AND DEMOCRACY IN AFRICA: THEORETICAL NEXUS

A major observation in the democratization literature is the volume of studies on elections across different part of the world which comes to represent the spread of the democratic wave. Principally, theorizing democracy has always come with the institutionalization of elections. A number of studies have recognized the place of elections in a democracy (Hadenius and Torell, 2007; Lindberg, 2006; Babawale, 2003). Several global and regional studies have further confirmed that elections play an important role in the institutionalization and consolidation of democracy (Schedler 2002; Lindberg, 2006; Moehler and Lindberg, 2009; Adebanwi and Obadare, 2011). From a theoretical point of view, these studies have established causality between elections and democracy and make a strong case for elections in the consolidation of democracy (Lindberg, 2006, 2009). The most profound theory in this perspective has been Lindberg’s study on democracy and elections in Africa. In his work, he presented evidence which shows that election is significant to democratic development. Based on an analysis of 232 elections in Africa between 1990 and mid-2003, Lindberg (2006:145-150) argues that repeated elections appear to have a positive impact on human freedom and democratic values.

While, it is difficult to quantify civil-liberty, the Freedom House strong methodological indicators which have become globally recognized for measuring democratic nature of countries exemplify the institutionalisation of liberty through elections (Lindberg, 2006). Through participation, competitiotion and legitimacy, Lindberg espouse the synergy between election and democratic freedom. He identified six key areas which show the impact of elections on freedom and democratic development. These areas include: citizen becomes voters, democratic lock-in mechanism, self-fulfilling prophecies, civic organization, institutional roles and strengthening [judiciary, court, police and other state security apparatuses] and media independence (Lindberg, 2006: 99-118). These principles no doubt strengthen the quality of elections but also have causative effect on democratic freedom. This observation was made by Lindberg (2006: 144), when he claimed that ‘no less than two-third of civil-liberty improvement in Africa; was direct effect of election’. Through free and fair elections, citizens are able to express their inalienable rights, make democratic choice, but also assert their democratic authority over their representatives (Fatai, 2008). Clearly, regularity of multiparty elections induces popular participation and freedom with incentives for democratization (Lindberg, 2006). As stated by Bratton (1998: 51) ‘if nothing else, the convening of scheduled multiparty elections, serves the minimal functions of marking democratic survival’.

In establishing a strong relationship between elections and democracy, Bratton (1998) investigated several methodological approaches which established causality between election and democracy, more so that research on third wave of democratization conceived election as the driver of transitions in Africa (O Donnel and Schimitter, 1986). As a mode of democratization, the empirical study of Norris, (1999), Schedler (2002) and Bunce and Wolchik (2006) also substantially supported the significance of election to democracy. For example, Bunce and Wolchik (2009: 2) studied 14 elections attempt in post-communist Europe and Eurasia between 1996 and 2006 and they submitted that ‘8 of them successfully resulted in the ousting of semi-authoritarian rules’. Consequently, ‘regular competitive, free and fair elections, representing the sovereign views of the citizen in any polity, do not only constitute a fundamental criterion; indeed they are the sine-qua-non in the evaluation of democratization and democracy’ (Sandbrook, 1998: 241). The place of election in a democracy therefore cannot be undermined, given that they have implication for the consolidation of democracy. As Samuel Huntington suggests in its ‘two turnovers test’, ‘democracy is consolidated, when a peaceful democratic change and alternation of power has occurred twice through competitive elections in which the incumbent loses to the opposition after the initial transition elections’ (Huntington, 1991:267). The logic behind the two turn-over test is the persuasive argument that election is the cardinal principle of democracy and the basis upon which democracy consolidates among other factors. As a consequence, democratic consolidation suggests the acceptance of the uncertainty of electoral outcomes in which political elites allow the baton of leadership to alternate in the interests of democracy (Przeworski, 1991). Although electoral turnover and power alternation itself is not a guarantee that electoral politics is immune from manipulation, they however have effect on the value system of the political elites. As a matter of fact, electoral turnover ‘generate shared levels of legitimacy between winners and losers in the populations’ (Moehler and Lindberg, 2009: 1449). This shared legitimacy is what Beetham (1994:160) claimed would promote ‘habituation to the electoral process, and make any alternative method for appointing rulers unthinkable’.

Thus, while it is acceptable that democratic consolidation consists of far more than elections, the reality across African region is that some countries are democratizing through the mode of elections. A significant number of African countries have produced good results in the conduct of elections and are peacefully consolidating their democracy. It is in this context that the theoretical proposition in this paper provides the template for understanding electoral democracy in Africa, by demonstrating that Nigeria’s latest electoral experience of 2015 has a significant consequence for the country’s drive towards democratic consolidation.

NIGERIA’S ELECTIONS AND DEMOCRATIZATION SINCE 1999

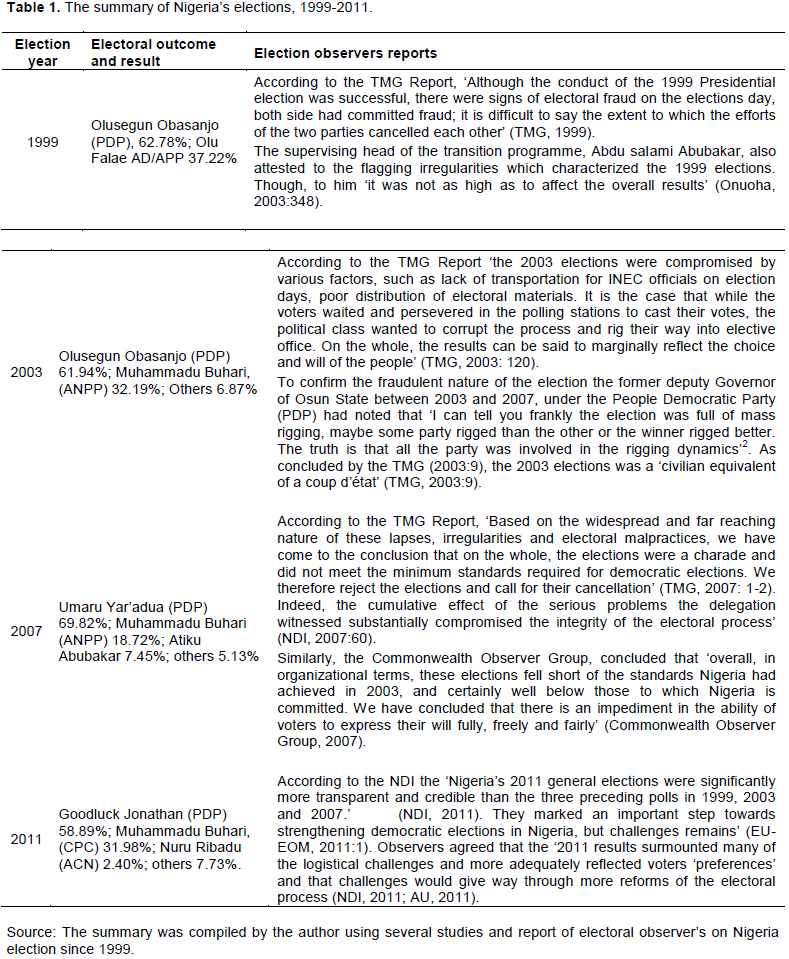

Considering the place of election in a democracy, Nigeria has institutionalised numbers of elections since the return to civilian government in 1999. These elections include those conducted consecutively since 1999, 2003, 2007, 2011 and 2015. With the exception of the later, nearly all of these elections have been condemned on the basis of their flaws. They have all been unacceptable to major stakeholders in the electoral process (Omotola, 2013). The rejection of elections under the latest democratization struggle since 1999 also follows similar patterns of the country’s political history, in which controversial and irregular elections has been the bane of the country’s democratization process. The inability of the political elites, in the post-independence Nigeria to engender free and fair, credible electoral elections was the root causes of the wanton political crisis that led to the first military intervention in politics in 1966. While it can be acknowledged that the military themselves are not better manager of democratization as indicated by their endless transition; the frequent manipulation of the electoral process either by the civilian counterparts is suggestive of the malevolent behaviour of the political elites to subvert democracy against the wish of the people. The crisis of electoral democracy in 2003 and 2007 in which both elections were dubbed the worst in the democratic history of the country is the basis upon which elections have become the façade of democracy (Obi, 2011, Agbaje and Adejumobi, 2006). Although there were improvement in the management of the 2011 elections, several studies and reports of domestic and international election observers have indicated that the potentials of Nigerian elections since 1999 have been in decline with consecutive ones not better than the preceding ones (Omotola, 2013). The repercussions of such are in consonance with the summary of the electoral process and reports of the election observers since 1999 as demonstrated in Table 1.

A major factor which gives plausible explanation to the perverted nature and volatility of Nigeria’s electoral process are chiefly the weakened electoral management and ideologically porous political parties. Nigeria’s electoral process has been entrenched in the crisis of electoral management and administration since 1999. The frailties of electoral institutions are illustrated by the fact that no elections have been conducted in Nigeria since 1999 without any serious electoral manipulations and controversies. As stated by Agbaje and Adejumobi (2006:31), ‘The INEC for example is generally known to have been grossly deficient in autonomy and capacity over the years’. Three major factors have been central to this. The first is the issue of autonomy, the second is the security of tenure and the third is the funding of the electoral body. The lack of autonomy has been responsible for why INEC habitually compromise, and easily been predisposed to manipulations by the president and their agencies (Omotola, 2013). The backlash of INEC autonomy is even more worrisome when the ruling party also holds majority in the parliament. This is the case between 1999 and 2011 when PDP used its majority in the National Assembly to influence and prevent due process in screening of INEC nominee presented by the president (Omotola, 2013). This factor also coincided with the insecurity of tenure of office of the INEC chairman and commissioners. In most cases, INEC officials lack job security, which undermine the security of the electoral process. Most electoral officials for fear of been removed compromised under severe executive control and influence. Those with un-uncompromising stance have been relieved of their duty (Onapajo, 2015). History is replete with the case of Professor Eme and Awa and Humphrey Nwosu, who were removed from office in 1989 and 1993 for their disagreement with the president on issues of electoral management (Agbaje and Adejumobi, 2006).

Although funding challenge of INEC has been resolved through the consolidated account, the executive in most cases has been in the habit of deliberately delaying or starving INEC of funds to undermine them or forces them to compromise. Consequently this has resulted in inability of INEC to prepare and plan effectively for elections and carry out an effective electoral administration (Omotola, 2013). The absence of autonomy by INEC has also been complicated by the absence of internal democracy in political parties. Most political parties in Nigeria lack basic democratic norms and principles, reducing party primaries to “jamborees where executive decisions are vetted” (Omotola, 2013: 192). Such desperate moves are extended to the electoral process, where political godfathers or so called party leaders, adopt anti-democratic measures ranging from vote-buying, intimidation, manipulations and violence to win elections. It is under such circumstance the Nigerian electoral process has been reduced to the prevalence of “do or die affair” where electorates ‘vote do not count’ and what is palpable the choicelessness of the people.

While it can be argued that Nigeria’s electoral process since 1999 has been characterized by fraud and manipulations resulting from factors mentioned earlier, the regularities of elections have implication for repeated democratic behaviour which reinforces democratization (Lindberg, 2006). As further stressed by Lindberg “election in new democracy does not signify the completion of the transition to democracy but rather they foster liberalization and have self-reinforcing power that promotes increased democracy in Africa political regime”. Contrary to the previous elections which were characterized with fraud and manipulations, reinforcing the belief that election is just a mere process of little worth to democratization. The credibility and integrity of the 2015 elections has promoted confidence in democracy by institutionalizing competitive and inclusive free and fair credible elections.

This view was derived from the field work I conducted on Election and Democracy in 2014

ELECTORAL REFORM AND INEC PREPARATION FOR THE 2015 ELECTIONS

As a consequence of the importance of the 2015 elections, the electoral management body in line with the recommendation of the Electoral Reform Committee (ERC) and the 2011 Electoral Act instituted a number of institutional reform to enhance the transparency and accountability of the electoral process. These reforms gather momentum and depth for the electoral process, by considerably increasing the degree of trust on INEC (Onapajo, 2015). Prior to the institutionalisation of the reforms, INEC introduced a new biometric voter’s registration, a re-modified Open Ballot system (MOBS), effective production methodology and securitization of election materials. It also presented a new structure for the revision, collation and declaration of election results and enhanced the transparency of voting procedures (Jega, 2013: 3). There was also the introduction of the Inter-agency Consultative Committee on Election Security (ICCES) to ensure security of the entire electoral process.

Following the earlier discussed, INEC introduced a number of reforms process and initiatives which could be characterized into three main proportions. The first has to do with the structural reform which addresses issues relating to INEC, as an electoral commission. The second is premised on specific policies to improve the quality of the election. On the other hand, the third is driven by effective planning and preparations as they speak to the question of strategies and logistics (Jega, 2013: 6). As regards the structural reforms, INEC restructured the commission to enhance their autonomy and reliability. A profound step taken in this direction was the immunization of the Resident Electoral Commissioners (RECs) from the influence of the state governors by ensuring adequate facilities and logistic without necessarily requiring the assistance of the states government (Momoh, 2015). This was contrary to previous practice where the RECs are usually on the fringe, relying on the state governors for logistical supports, and the implication for undue influence and electoral manipulation. In addition, INEC enhances the capacity of its affiliates to train staffs and enhance efficient performance of the commission. The Electoral Institute (TEI) was tasked with serious research and training for the purpose of delivering transparent and accountable electoral process (Momoh, 2015).

With respect to policy initiatives, INEC introduced the Permanent Voter Cards (PVCs) and electronic card reading system. These biometric technological innovations were significant steps in arresting the challenge of electoral malpractices and fraud. The PVC and card reader, through the biometric check serve as system of restraints against electoral fraud and irregularities. By this it ensures that voters are at the correct polling unit where they registered’ and ‘that their fingerprints match with those on record and on their card’ (Situation Room, 2015: 3). This process was entirely different from the previous exercise where registrations of voters were characterised by multiple registrations and voting. Furthermore, INEC also introduced the National Inter-Agency Advisory Committee on Voter Education and Publicity (NICVEP). This is with a view to enhancing voter education and political culture of Nigerians (International Crisis Group, 2015: 20). Apart from the NICVEP, there was also the inter-party dialogue created to promote an enduring platform for political parties’ interactions and stakeholders’ peace agreement. On the issue of planning and logistic, INEC collaborated with unions of transport associations to move voting materials to the polling centre as quickly as possible before commencement of elections and ensured that elections commenced at the same time across the country (Momoh, 2015).

Granting that some of these innovations raised concern in the period leading to the elections, the commitment of INEC to credible electoral process ensured that the 2015 election was a success. For example, the lack of PVC distribution at the registration centre after the CVR exercise and the perceived favouritism in the distribution, though, heightened tension on the preparedness of INEC for the elections, its decision to postpone elections to ensure enough time for the effective distribution of PVC in the face of government influence has been widely acknowledged (Odebola et al., 2015). Despite pockets of concerns resulting from the inability of card readers to verify electorates’ fingerprints in some polling centers during the presidential election, their improvements in the National Assembly election eventually reduced concerns and tensions resulting from the electoral process.

The recommendation of the ERC represents the first fundamental effort of the government in addressing the general problem associated with the electoral process. Given that the previous attempts were merely ad-hoc approaches, the ERC reports convey the intention of the government ‘to examine the entire electoral process with a view to ensuring that the quality and standard of general elections are raised and thereby deepening Nigeria’s democracy’ (Federal Government of Nigeria, 2008: 2). Having undertaken a nation-wide consultation and dialogue, as well as calling for memorandum; the ERC under the Chairmanship of Justice Muhammadu Uwais discovered the character of the Nigerian elite, weak democratic institutions, negative political culture, weak constitutional and legal framework and lack of independence and capacity of the EMBs were responsible for the protracted challenge of the electoral process. Against this backdrop, ERC provided a set of recommendations which critically address the major problem of the electoral process. The recommendations particularly covered areas concerning the independence of the EMB; internal democracy in the political parties; election jurisprudence; and the structure of election timelines (see EU EOM, 2011). These set of recommendation has implication for the branches of government – executive, legislature, judiciary, the EMB, political parties, electoral system, security forces, media, religious and traditional institutions, civil society organisations, and international organisations. As a result of the widespread acceptability of the report, the Federal Government instituted some of the recommendation of the ERC through the amendments to the 1999 Constitution and the signing of the 2010 Electoral Act and framework relating to the electoral process.

Apart from the ERC recommendation, there was also the Independent Assessment group commissioned by the government through the USAID/DFID which also recommended among others things the restructuring of INEC to be truly autonomous in administration and immune from executive influence and control, its funding to be charged on the consolidated account just like the National Assembly and the Judiciary and that elections should be open to confirmation and electoral dispute timely adjudicated.

This is a voting system that allows for open accreditation, while voters wait to secretly vote for their choice candidates. This is different from the Open Ballot System where voters queued behind their choice candidates to vote and voting done in the open.

Introduction of serial numbering and colour coding of ballot papers and results sheets and security coding of ballot boxes.

Results are pasted at polling units and collation centers.

This is aimed at ensuring “a coordinated engagement of all the security agencies during election periods” (Jega, 2013, p.3).

Although the postponement of the election was a violation of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria which says that, election must be conducted 3month before swearing in, the degree of understanding and maturity displayed by the political elites ensured that the electoral process remain on course despite initial apprehension by the opposition party, particularly the APC. (See Premium Times January 11 2015).

‘out of the 182, 000 card reader procure by INEC, about 300 of them reportedly failed (See Orji, 2015:1).

NIGERIA’S 2015 DEMOCRATIC ELECTIONS

Despite the widespread concern generated by the card readers’ machine, the problem of PVC distribution and postponement of election, Nigeria successfully conducted a legitimate election on March 28 and April 11, 2015, in which former military General Muhammadu Buhari was declared winner in the presidential election (Owen and Usman, 2015; Onapajo, 2015). In the election, the opposition candidate Muhammadu Buhari of All Progressive Congress (APC) scored 15, 424, 921 (53.96) votes, while the incumbent President; Goodluck Jonathan secured 12, 853, 162 (44.96%) of the valid votes (INEC, 2015). At the same time, in the National Assembly elections, the opposition APC won 64 seats out of 109 seats in the Senate, and 214 of the 360 legislative seats in the House of Representatives. The PDP won 45 seats in the Senate and 125 in the House of Representatives (INEC, 2015). Even though the APC constituted the majority in the National Assembly, they did not have overwhelming majority of the seats, as the previous electoral experience under the PDP since 1999 demonstrated.

While it cannot be said that the entire electoral process was not without some drawbacks, they however, did not undermine the credibility of the elections. This position reflected in the Transition Monitoring Group; TMG (2015) when they noted that ‘since we have 37 states including the federal capital territory and 774 local governments. I think if we have irregularities in 4 to 5%, they cannot be used to judge the election as not valid’. This sentiment was also echoed by the European Union Election Observer Monitoring group which noted that, ‘the conduct of the 2015 Presidential elections was generally peaceful and transparent, there was no evidence of centralised systemic fraud, although few attempts at manipulations were observed. Those persisting challenges would probably give way with more reform and improvement in the electoral process’ (EU-EOM, 2015:11). More importantly, the African Union Election Observation Mission (AUEOM) summed up the trajectories of the 2015 elections when they poignantly concluded that ‘In view of the observations and findings, the 28 March 2015 elections were conducted in a largely transparent and peaceful manner and within a framework that satisfactorily meets continental and international principles of democratic elections’ (AU-EOM, 2015).

The positive outcome of the elections was not unexpected considering the number of reforms initiated by INEC which conferred legitimacy and trust on the country electoral process. As noted by Orji (2015:2), ‘the elections demonstrated that processes of gradual reform can improve the legitimacy of the electoral system in the short run and may consolidate the democratic system in the long run’. The political will demonstrated by the incumbent president to concede defeat and accept the outcome of the elections by gracefully congratulating the victorious president also confers high degree of credibility and legitimacy on the elections. The democratic gains and fortunes emanating from these elections have not only demonstrated the imperative of elections to democracy, but also stimulated its potential for democratic consolidation.

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE 2015 ELECTIONS AND DEMOCRATIC CONSOLIDATION IN NIGERIA

As consequence of the aforementioned, the 2015 election was significant in several aspects of the country’s electoral process. Apart from occasioning a fundamental break from the electoral past in which flawed and controversial election had become an institutionalized feature of the democratization process, it restored the reputation of Nigeria as a leading democratic promoter in Africa (Omotola, 2015). By its legitimacy, Nigeria returned to the path towards democratic stability and consolidation (Orji, 2014). Nigeria’s drive towards democratic consolidation can only be situated within the context of credible elections and institutionalisation of key liberal democratic principles such as elite acceptance of electoral outcomes, electoral turnover and democratic change, elite pacts and consensus on democratic rules of engagement, coordinated opposition and coalition politics, reforms and effective management of elections among others. The 2015 elections promoted these principles as a reflection of its significance to democratic consolidation in Nigeria.

Acceptance of electoral outcome

Unlike the previous elections whose process and outcome were usually rejected for lack of legitimacy, the 2015 election was generally accepted by the broad spectrum of stakeholders. This conferred legitimacy and acceptability on the elections, as the incumbent President Goodluck Jonathan conceded defeat to the opposition candidate; Muhammadu Buhari, even before the declaration of results, despite the reflection of ethnic and religious trend in the voting pattern. Such legitimacy had moderating effect on the political landscape. As stated by Orji (2015: 2) ‘President Jonathan’s early acceptance of defeat had a tremendous calming effect on the charged political atmosphere and reinforced the message of peace promoted by Nigerian Civil Society and International Community’

This democratic behaviour was a clear departure from the experience of the past where all presidential elections since 1999 have been subject of contestation, and often decided by the court. The new value-system no doubt suggests an improvement in the electoral process, but also attests to a changing attitude of the political elites to accept democratic decisions regardless of who is affected. Accepting the verdicts of the electoral process by democratic actors, therefore no doubt ‘builds confidence among a range of actors that political leaders intend to follow the rules of the game, and this moves countries closer to a point where democracy becomes the only game in town’ (Przeworski, 1991).

The credibility of the election has not only promoted trust in government institutions, but also enhanced peaceful democratic change and power alternation (Cheeseman and Hinfallar, 2009). As argued by Rakner and Svasand (2013: 4), ‘the legitimacy of the electoral process hinges on the electorates and candidates perception that the process has been conducted in a way that does not in advance ensure a certain outcome’. When this occurs, democratic actors know ‘the certainty of the process, but uncertainty about the outcome’ (Przeworski, 1991: 40-41). This is what Omotola (2013: 180) referred to as the ‘genuine, non-instrumental and intrinsic support for democracy’.

Electoral turnover and democratic change

Given the institutionalisation of electoral turnover, the 2015 elections have been adduced as significant in the democratic project of Nigeria. For the first time, since 1999 in the democratic history of the country, Nigeria witnessed genuine electoral turnover, where an incumbent regime will peacefully transfer power to the opposition. This did not only ensure that it is transferred from one regime to another, but further suggests that ‘entrenched, corrupt and authoritarian regimes can be unseated, creating opportunities for further political liberalization’ (Cheeseman and Hinfallar, 2009: 59). Prior to the 2015 electoral turnover, the Nigerian state had suffered a serious democratic setback, resulting from the backlash of the PDP regime. Such backlash is evinced by manipulation of the electoral process, and major democratic institutions including INEC, political parties and legislature. Many of these institutions lost their capacity and trust from democratic actors; they also became instruments of authoritarian streak.

The credibility of the electoral process, resulting in the 2015 electoral turnover therefore offered motivation for various shades of democratic actors, including the winner and looser to accept the democratic process and outcome as a true reflection of their collective interest. As argued by Moehler and Lindberg (2009: 1463), turnovers and alternations ‘establish a self-reinforcing equilibrium by providing incentives for elites on both sides to play by the democratic rules of the game’. Obviously, electoral turnover is unarguably a crucial cornerstone of successful democratization (Lindberg, 2006; Przeworski, 1991); it not only injected legitimacy and popular support for democracy, but also solidified the process for the consolidation of democracy.

Elite pact and consensus

It can also be argued that the 2015 elections also cemented some degree of trust and consensus among the broad spectrum of political elites. Prior to the conduct of the 2015 elections, Nigeria’s political elites were largely disunited along a military and conservative civilian elites and the progressive and strong oppositional force. The former have dominated the democratic space, enjoying access to political power and economic resources in a context which strengthens their domination. The signing of the Abuja accord by these groups and other major stakeholders played a prominent role in forging a consensus among the broad spectrum of political elites during the process and outcome of the 2015 elections. The political elite not only shunned electoral violence; they also generally accepted the outcome of the elections. As noted by Bratton and Van de Walle (1997:235) ‘democracy is not possible without democrats’; the value system and disposition of the elites are the principle upon which democracy can be nurtured’. Elite can indeed sustain and stabilize democracy when they are consensually united, obeying the rules of the game and respecting institutional norms (Higley and Burton, 1992).

Although elite consensus sometimes does not entirely suggests agreements, as their rational-choice and strategic consideration often create conflicts, the principle of ‘restrained partisanship and institutional commitment’ in the words of Di Palma (1973) motivates the underlying behaviour of the elites in sustaining the credibility of the electoral process. To put it aptly, ‘when political elites act within the institutional framework of democracy, they constitute the equilibrium of the decentralized strategies of all the relevant forces’ (Przeworski, 1991: 26). In other words, the equilibrium alluded to by Przeworski is the one that generates the political line, between formal rules and the behaviour of political elites. In actual fact, the acceptance of the electoral outcome by the incumbent president and his camp, without necessarily undermining the democratic process either by rejection of the elections or deploying state instrument to perpetrate violence suggests that elite pact and consensus are central to democratic stability and consolidation. As postulated by Schedler (1998: 67), ‘rolling back of anti-democratic challenge’ presupposes that political actors are willing to play the game according to established rules and regulations’ (Schedler, 1998: 69). By conforming to the rules of engagement and democratic outcomes political elites are ‘giving up the habit of placing themselves above the law and accepting mutually accepted norm’.

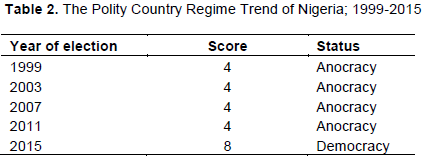

This is an ‘improvement in the behavioural and attitudinal disposition of the political elite’ (Diamond, 1999: 69). Such attitude displayed by political actors in the 2015 electoral process belies the potential for conflicts, and also shapes intrinsic democratic culture and value, in which democratic actors come to accept democratic verdict, regardless of their interest and idiosyncrasies. The credibility of the election has also promoted increase in civil and political liberty. This is summed up by the Polity Scores index in Table 2.

The emergence of the All Progressive Congress (APC) benefited from the setback suffered in the PDP as a consequence of deep-seated factionalisation and defection in which five Governors breakaway from the party to form a new party called new-PDP. This party later aligned with a coalition of major opposition party to form a mega party called APC. The coalition parties include the defunct Action Party of Nigeria (ACN), Congress for Progressive Change (CPC), All Nigerian People’s Party (ANPP), and a breakaway faction of All Progressive Grand Alliance (APGA).

Despite the transparency of the elections, the case of under-age voting (in the Northern part) and inflated figures were observed in major states in the Niger-delta especially in Rivers, Akwa-Ibom, Bayelsa, Delta, etc). This is also not isolated from reported cases of ballot snatching, made possible with the support of the security officers in some others states during the elections (EU-EOM, 2015:12; TMG, 2015).

The Abuja Accord is the framework of the National Peace Committee, (under the coordination and supervision of the former United Nation Secretary-General; Kofi Anan and the former scribe of the Commonwealth of State, Emeka Anyaoku, former Military head of state; Abubakar Abdusalami and other prominent interfaith religious leaders) in which political elites, especially the 14 Presidential candidates are made to sign and commit to peace agreement that they would conduct their campaigns based on issue-based, peacefully accept the electoral results, refrain from using inflammatory language and denounce act of violence or incitement during and after elections as well as refraining their ardent followers from such. (NDI, 2015: 9).

In the context of the declining freedom, the polity score categorized Nigeria as Anocracy (regimes located between autocracy and democracy) between 1999 and 2011. The reason behind this was due to the frequent manipulation of political institution (especially the electoral management body and the Police) arbitrary exercise of political power and perverted electoral process since 1999. During these periods Nigeria had a status of 4 in his polity score. These scores suggest the institutionalization of authoritarian streak and weakening of state institutions by political leadership. However, the competitiveness, openness and participation in the 2015 general elections and the extent of checks on the executive authority enhanced the country’s polity score from 4 to 8. This culminated in the categorization of the country as democratic in 2015.

Coordinated opposition and coalition party

A major factor which shaped the significance of the 2015 elections is the viable coalition politics. For the first time, opposition political parties were able to forge ahead along a common front to wrestle political power from the incumbent regime. This is unlike past experiences where coalition building and framework has been hampered by the absence of common ideological trappings essential for coalition politics. The reason for this was adduced by Ibrahim and Hassan (2013:190) when they noted that political parties in Nigeria ‘lacked internal discipline and ideological norm, which is necessary to maintain coalition arrangements’. Beyond this, the plural and diverse political sub-culture in Nigeria is antithetical to coalition formation (Kadima, 2014:237). The need for effective and stable coalitions prior to the 2015 election, therefore, spanned from the dominance of one party as the case of PDP suggests since 1999. It should therefore be stressed that the PDP dominance has contrived the democratic spaces, giving less opportunity to the opposition party. Apart from winning all executive/presidential positions both at the federal and state levels, it has also amassed the entire legislative seats in the National Assembly and State House of Assemblies since 1999 (Omotola, 2015). Such dominance has almost become institutionalised as the attitude of PDP suddenly became driven towards one party state, especially under President Obasanjo regime, 1999-2007. Accordingly, Vincent Ogbulafor, the former PDP chairman had bragged that ‘PDP will rule Nigeria for the next 60 years’ (cf. Isoumunah, 2011:51). Indeed, the 2003 and 2007 were not only fraudulently rigged; they were used to undermine democratic institutions. The confirmation of this is the way the ‘electoral processes were often garrisoned, infused as they were by the use of the power of incumbency, disproportionate use of state resources, including security agents, national treasury, state owned media and so on’ (Omotola, 2015:7).

It is under this condition that the opposition parties came together to form a coalition platform which dislodged the PDP. This idea gave rise to the emergence of the All Progressive Congress (APC). The APC is an assemblage of the defunct Action Congress of Nigeria (ACN), Congress of Progressive Change (CPC), All Nigerian People’s Party (ANPP) and the breakaway faction of the All Progressive Grand Alliance (APGA) under the leadership of Rochas Okorocha, the Governor of Imo State. Desirous of unseating the PDP, the APC gained more strength with the alliance of the disgruntled element which pulled out of the old PDP, led by Abubakar Atiku; former Vice president, Abubakar Baraje; a former National Secretary of the old PDP, Olagunsoye Oyinlola, a former Governor of Osun state and National Secretary of the old PDP. These disgruntled elements were followed by seven governors elected under the platform of PDP. This further strengthened the opposition party in terms of resources and support (Omotola and Nyuykonge, 2015). As argued by Owen and Usman, (2015:4) ‘the APC coalition remained cohesive, unlike previous attempt to unite the opposition drawing strength and membership from a fractured PDP’. Though the opposition APC was initially doubted because of ideological differences and the breakdown and crises, which usually characterised coalitions, the competitive, transparent and credible primaries conducted by APC restored some measure of trust on the party. The trust was also amplified by the change mantra which APC identified against the prolonged hegemonic politics of PDP which continued to bring untold hardship to the people (Omotola, 2015). The coalition arrangement not only challenged the incumbent party in a competitive election leading to electoral turnover, they also promoted. a new sense of democratic optimism largely driven by the need for a regime change in Nigeria

Effective management of elections by electoral body

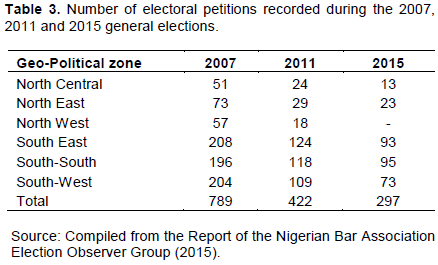

The significance of the 2015 elections is also underlined by the INEC management of the election. Against the backdrop of poor preparation, executive interference and logistic challenge across the country, INEC under the prolific leadership of Prof. Attahiru Jega gave Nigeria a befitting, transparent and credible election. Indeed, Nigerians’ evaluation and credibility of INEC have a stronger impact on their perception about elections quality. As a measure of effective management of the electoral process, INEC undertook a number of significant reforms which were central not only to the rules of engagement among democratic actors, but also to ensuring credibility of the electoral process. Many of these reforms and their importance have been analyzed earlier. Major ones among them include, introduction of the PVCs and biometric technology to reduce electoral fraud and manipulations before and during the election. In addition the use of reputable academics as Returning Officers, devoid of political influence also enhanced the reputation of the elections. Although issues of malfunctioning card readers, postponement of elections, non-availability of voters’ card, poor accreditation of election observers surfaced, INEC’s ingenuity in addressing these problems through manual accreditation and rescheduling of elections in 300 polling units where the problem occurred were extremely significant in engendering the legitimacy and credibility of the electoral process (Onapajo, 2015). Table 3 shows the comparative cases of electoral petitions recorded in 2007, 2011 and 2015?

The table indicates that there was a far-reaching reduction in the number of elections petitions and litigations filed by candidate challenging the result of the 2015 elections. The reduction was occasioned by the drop in the number of post-election petitions from 789 in 2007. It further reduced from 422 in 2011 and to 297 cases in 2015. Such drop is not unconnected to the peaceful and transparent electoral process and outcome in 2015 elections in which many candidates and their parties accepted the outcome of the poll as a true reflection of the democratic process. This disposition was contrary to the previous practice where elections have often been the source of electoral crisis and rejection. The reduction in the cases of election petition is not only an indication that the election was credible, but also suggestive that it was properly managed by INEC.

Efficient civil society organizations

While INEC has been acknowledged for their role in the management of the electoral process, the vigilance of the civil society organisations has been largely attributed to the significance of the 2015 election. It should be stressed that in the build up to the elections the coalition of civil society organizations held several meetings and discussions among major stakeholders. They held consult and dialogue with INEC, political parties, religious leaders and Kofi Annan; former United Nation Secretary General among others on INEC preparation and acceptable conduct from stakeholders in ensuring peaceful electoral process (Owen and Usman, 2015). As a whistleblower to the electoral process, the CSOs ensured that correct procedures were followed. For example, the postponement of the elections from 14 and 28th 2015, respectively by INEC on the claim that these elections would undermine the legitimacy of the electoral process was condemned in strong term by the CSO. According to them ‘we believe the postponement of this elections, for whatever reason, will undermine whatever modicum of legitimacy the electoral process still has and may ultimately be the trigger for massive unrest, violence and armed conflicts, effectively setting the stage for civil unrest’(The Nation May 13, 2015).

More importantly, the Nigerian Civil Situation Room, coalitions of about 60 CSOs also kept an eye on the electoral process. By monitoring and observation elections, they ensured that elections are counted on the spot, but monitors also transmit the result immediately to the situation room for cross-examination, verification and analysis in preparation for the declaration of the results. Indeed, the Situation Room has provided the medium for closely monitoring and improvement of the electoral process (Onapajo, 2015).

The polity Index scores captures regime authority on a 21 point scale ranging from 10 (a hereditary monarchy) to +10 (a consolidated democracy). The polity score can also be converted to regime categories: 3 part of categorization of autocracy (-10 to -6) anocracies (-5 to +5) and the three special values (-66-77 and -88) and democracy (+6 to +10). Senegal’s score was +7 (consolidated democracy). Nigeria’s score was +4, (anocracies) whereby from -5 to +5 is anocracies.

Despite criticism of Polity scores as methodological and ideological bias, there are as of yet no better alternatives which best explains level of democracy and the nature of regime authority across ccountries around the world. By drawing from Polity scores, we can ensure there is much wider degree of consensus and acceptability that might be otherwise being the case.

The regularity of election as a threshold of democratic consolidation in the post third no wave democratization is manifesting in the relevance of elections in Africa. While elections are easily not the only principle for consolidating democracy, their institutionalization has enhanced the prospect of democratization and consolidation. Indeed the presence of elections in several democratizing countries has generated optimism against the backdrop of past authoritarian and military regime which not only undermined liberty but also the democratization process. Under such circumstance, elections have not only caused democratization, but they have also shaped attitudinal and behavioural disposition of political elites in accepting the process and outcome of elections regardless of their interest or idiosyncrasies. This is the case with the 2015 elections, where democratic quality of elections had cause and effect, on democratic consolidation through electoral turnover and power alternation, acceptance of election result by stakeholders, elite pact and consensus among others. Despite the improvement in the electoral process and peaceful transfer of power, political choices remained compromised as vote buying and bullying of voters during the elections still remained a challenge to the electoral process. While it should be stated that these shortcomings did not undermine the validity of the elections, the 2015 elections no doubt enhances the legitimacy of the electoral process; it also reinforces the consolidation of democracy in Nigeria.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Adebanwi W, Obadare E (2011). The abrogation of the Electorate: An Emergent African Phenomenon. Democratization 18(2):275-310.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Agbaje S, Adejumobi A (2006). Do Votes Count? The Travails of Electoral Politics in Nigeria. Africa Development 31(3):25-44.

|

|

|

|

|

African Union Election Observation Mission (AUEOM) (2015). Release of AUEOM Preliminary Statement on Nigeria's Election.

|

|

|

|

|

African Union Election Observation Mission (AUEOM) (2011). Release of AUEOM Preliminary Statement on Nigeria's Election.

|

|

|

|

|

Babawale T (2003). The 2003 Elections and Democratic Consolidation in Nigeria. in Anifowose R & T. Babawale ed., 2003 General Elections and Democratic Consolidation in Nigeria. Lagos. Fredrick Hubert Stiftung.

|

|

|

|

|

Beetham D (1994). Conditions for Democratic Consolidation. Review of African Political Economy 21(60):157-172.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bogaards M (2007). 'How to Classify Hybrid Regime? Defective Democracy and Electoral Authoritarianism'. Democratization 16:399-423.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bratton M (1998). Second Elections in Africa. Journal of Democracy 9(3):51-66.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bratton M, Van De Walle N (1997). Democratic Experiments in Africa: Regime Transitions in Comparative Perspectives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bunce V, Wolchick S (2009) Democratizing Elections in Post-communist Central and Eastern Europe. Paper presented for the Conference on '1989: Twenty Years After'. University of California Irvine November.

|

|

|

|

|

Bunce V, Wolchick S (2006) Favourable Conditions and Electoral Revolutions. Journal of Democracy 17(4):5-18.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cheeseman N, Hinfallar M (2009). Parties, Platforms and Political Mobilisation: The Zambian Presidential Election of 2008.

|

|

|

|

|

Commonwealth Observer Group (2007). The National Assembly and Presidential Elections in Nigeria, 21 April 2007. (Report of the Commonwealth Observer Group). London: Commonwealth.

|

|

|

|

|

Diamond L (1999). Developing Democracy: Towards Consolidation, Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Di Palma G (1973). The Study of Conflicts in Western Society: A Critique of the End of Ideology. Morristown: General Learning Press.

|

|

|

|

|

European Union Election Observation Mission (EU-EOM). (2015). Second Preliminary Statement: More Efficient Polling Although Increased Incidents of Violence and Interference. Abuja. EUEOM.

|

|

|

|

|

European Union Election Observation Mission (EU-EOM) (2011). Nigeria: Final Report on the General Elections.

|

|

|

|

|

Fatai A (2008). 2007 General Election Campaign Strategy and Democratic Consolidation in Nigeria. Journal of Constitutional Development 8(2):15-32.

|

|

|

|

|

Federal Government of Nigeria (2008). Report of the Electoral Reform Committee (vol. 1 main report).

|

|

|

|

|

Hadenius A, Torrel J (2007). 'Authoritarian Regimes: Stability, Change and Pathways to Democracy, 1972-2003'. Journal of Democracy 18(1):143-57.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Higley J, Burton R (1992). Elites and Democratic Consolidation in Latin America and Southern Europe. New York: Cambridge University.

|

|

|

|

|

Huntington S (1991). The Third Wave: Democratization in the late Twentieth Century. London: University of Oklahoma Press.

|

|

|

|

|

International Crisis Group (ICG) (2015). Nigeria's Dangerous 2015 Elections: Limiting the Violence. Report 222:21 November 2015.

|

|

|

|

|

Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) (2015). 2015 Presidential Election Result.

|

|

|

|

|

Isoumuna AV (2011). Imperial Presidency and Democratic Consolidation in Nigeria. African Today 59(1):43-68.

|

|

|

|

|

Jega A (2013). Electoral Reforms in Nigeria: Prospects and Challenges. Lecture by the Chairman, Independent National Electoral Commission of Nigeria at the 7th International Electoral Affairs Symposium in Kuala Lumpur Malaysia.

|

|

|

|

|

Ibrahim J, Hassan I (2013). Nigerian Political Parties from Failed Opposition to Electoral Alliance Merger: The March towards the 2015 General Elections. Centre for Democracy and Development. Lagos.

|

|

|

|

|

Kadima D (2014). An Introduction to the Politics of Party Alliance and Coalitions in Socially Divided Africa. Journal of African Elections 13(1):1-24.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lindberg S (2009). Democratization by Election: A Mixed Record. Journal of Democracy 20(3):86-92.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lindberg S (2006). 'The Surprising Significance of African Elections'. Journal of Democracy 17(1):139-151.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Moehler D, Lindberg S (2009). Narrowing the Legitimacy Gap: The Role of Turn Overs in Africa's Emerging Democracy. Journal of Politics 71(4):1448-1466.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Momoh A (2015). The Jega I know —Momoh (interview). The News, 14 April.

|

|

|

|

|

National Democratic Institute (NDI) (2011). 2011 Nigerian Elections: Final Report. Washington DC and Abuja: NDI.

|

|

|

|

|

National Democratic Institute (NDI) (2007). Final NDI Report on Nigeria's 2007 Elections. Washington DC and Abuja: NDI.

|

|

|

|

|

National Democratic Institute (NDI) (2015). Statement of the National Democratic Institute International Election Observer Mission to Nigeria's March 28 Presidential and Legislative Elections.

|

|

|

|

|

Nigerian Bar Association Election Observer Group (NBA-EG) (2015). Sustaining Gains of 2015 General Elections: Perspective of Nigerian Bar Association Election Working Group.

|

|

|

|

|

Norris P (1999). 1st edition: Driving Democracy: Do Power Sharing Institutions Works? New York/Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Obi C (2011). Taking back our Democracy? The Trials and Travails of Nigerian Elections since 1999. Democratization 18(2):366-387.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Odebola N, Alechenu J, Obe E, Oluwole MJ, Affe M, Chiedozie I, Ogundele K, Nwogu S (2015). PDP Panics over high PVC Collection in APC Stronghold. Punch 11 January.

|

|

|

|

|

O Donnel G, Schimitter P (1986). Transition from Authoritarian Rule: Tentative Conclusion about Uncertain Transitions. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Omotola JS (2015). Opposition Merger, Electoral Turnover and Democratization in Nigeria.

|

|

|

|

|

Omotola S, Nyuykonge C (2015). Nigeria's 2015 General Elections: Challenges and Opportunities. ACCORD Policy Brief Vol 33 March.

|

|

|

|

|

Omotola JS (2013). Trapped in Transition? Nigeria's First Democratic Decade and Beyond. Taiwan Journal of Democracy 9(2):171-200.

|

|

|

|

|

Onapajo H (2015). The Positive Outcome of Nigeria's 2015 General Elections: The Salience of Electoral Reforms. The Round Table: Commonwealth Journal of International Affairs.

|

|

|

|

|

Onuoha B (2003). A Comparative Analysis of General Elections in Nigeria. In R. Anifowose & T. Babawale (Eds.), 2003 General Elections and Democratic Consolidation in Nigeria. Lagos. Fredrick Hubert Stiftung.

|

|

|

|

|

Orji N (2014). Nigeria's 2015 Election in Perspective. African Spectrum 49(3):127-150.

|

|

|

|

|

Orji N (2015). Nigeria's 2015 Elections: Lessons and Prospect for Democratic Consolidation. African Peacebuilding Network Briefing Note Number 1 June.

|

|

|

|

|

Owen O, Usman Z (2015). Briefing: Why Goodluck Jonathan lost the Nigerian Presidential Election of 2015. African Affairs 14(456):455-471.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Przeworski A (1991). Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rakner L, Menochal AR, Fritz V (2007). Democratisation's, Third Wave and the Challenges of Democratic Deepening: Assessing International Democracy Assistance and Lessons Learned. Working Paper1.

|

|

|

|

|

Rakner L, Svassand L (2013). Competition and Participation, but no Democracy: The Politics of Elections in Africa's Feekless Regime. Statsvetenskapelig Tidskrift 115(4):365-384.

|

|

|

|

|

Sandbrook R (1998). Liberal Democracy in Africa: A Socialist Revisionist Perspective. Canadian Journal of African Studies 22(2):240-67.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Situation Room (2015). Why Permanent Voters Card and Card Readers Should Matters to Voters. Abuja: Policy and Legal Advocacy Centre PLAC).

|

|

|

|

|

Schedler A (1998). What is Democratic Consolidation?. Journal of Democracy 9(2):91-107.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Schedler A (2002). The Menu of Manipulation. Journal of Democratization 13(2):36-50.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

The Nation (2015). 'How Civil Society, Citizens Contribute to Change' Wednesday May 13th 2015.

|

|

|

|

|

Transition Monitoring Group (TMG) (2015). Preliminary Statement on the 2015 Presidential and National Assembly Elections.

|

|

|

|

|

Transition Monitoring Group (TMG) (2007). An Election Programme to Fail (Final Report of the April 2007 General Elections in Nigeria).

|

|

|

|

|

Transition Monitoring Group (TMG) (2003). Do Votes Counts? Final Report of the 2003 General Elections in Nigeria. Lagos: TMG.

|

|

|

|

|

Transition Monitoring Group (TMG) (1999). Interim Report of the Transition Monitoring Group on the Presidential Elections on 27 February 1999.

|

|