This study applied a documentary and literature review method to gather the required information on nature and performance of opposition parties and the prospects of multiparty politics in Tanzania. Relevant literature and documents which were reviewed included files on past Tanzanian general elections starting with the pre-independence elections that involved the Legislative Council Election which took place on February 1959 to the most recent 2015 general elections. Some of the documents were accessed through the African Elections Database’s website and the United Republic of Tanzania National Electoral Commission (NEC) official website. In addition to the mentioned documents, in this study various literatures were reviewed. The reviewed literature among other things debates on the nature, structure and performance of the opposition parties during the past Tanzanian general elections. The information obtained from these sources helped to answer the key research question.

There is a common agreement among social scientists that no single study can be done without a literature review. Literature review and or documentary review have been used by social science researchers mainly as part of group of methodologies of data collection. However, literature review can stand alone as robust technique of data gathering. Use of literature review technique in gathering data is very common within the field of political science. For instance, Malipula (2014) conducted a literature review to establish a structural and historical explanation that attributes lack of ethnic salience in Tanzanian politics to a particular ethnic structure, to certain colonial administrative and economic approaches, and to a sustained nation-building ethos. Likewise, Montero and Gunther (2003) used literature review to make a critical reassessment of political parties in Western Europe. Furthermore, Disch et al. (2009) used the literature review method to study the anti-corruption approaches. Also, Bogaards (2014) used similar methodology to study electoral alliances in Africa. Summary of the key literatures reviewed in this study is presented in Table 1:

Qualitative data were analyzed through the use of Content Analysis where information gathered from the documents and literatures were transcribed into word document. Thereafter, key themes and patterns were formed and codes established. The qualitative information were then integrated with quantitative information mainly from the African Elections Database (2011) and the United Republic of Tanzania National Electoral Commission (NEC) Official Website (2015) to provide more meaningful analysis. In analyzing quantitative data, descriptive statistics were conducted where percentage and frequencies on past elections results were computed. Results were then presented in tables, to show how each of political party performed as far as Presidential and Parliamentary election were concerned.

The history of Tanzania’s General Elections dates back to pre independence 1950s. The 1958/1959 Legislative Council Election (Figure 2) saw Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) which later in 1977 merged with the Afro-Shiraz Party to form ‘Chama Cha Mapinduzi’ (Revolutionary Party which is the current ruling Party in Tanzania) wining with 28 seats out of 30 available seats compared to other political parties who had only 2 seats. It should be noted that this was the Multiparty Election.

The votes TANU gathered from this election suggests that it was founded on a very strong foundation and was made to last longer. From the beginning, Tanganyikans had believed in TANU and its leadership under Julius Nyerere. The current CCM is still reaping fruits of this strong foundation.

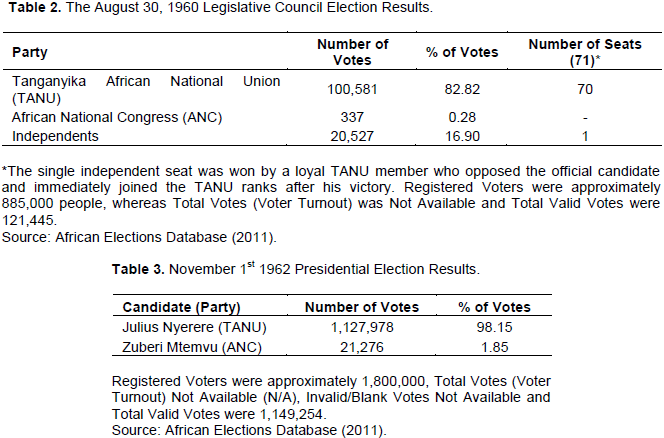

Tanganyika had another pre-independence Legislative Council elections held on 30th August, 1960. Unlike the September 1958 elections, this time the electoral authorities allocated more number of seats (71) to be contested by political parties. Likewise, during this election it was TANU which won all seats, because even the single independent candidate who won a seat in Mbulu was a loyal TANU member who opposed the official candidate and immediately joined the TANU ranks after his victory. The African National Congress (ANC) which was the only party challenging TANU did not win any seat and ended up having a total of 0.28% of votes (see Table 2). At this point TANU had established itself as the only strong unifying political party which can lead the country. Leaders of ANC later on established new political parties to oppose TANU now CCM, however, they did not succeed. For example, the ANC which was formed by former TANU members who broke away from TANU in 1958 due to dissatisfaction regarding TANU’s position and ideology on Africanization and especially TANU’s definition of ‘Africanization’ which included people of all races who were citizens of Tanganyika was purely a discriminatory political party. In spite of sharing the same name with the ANC of South Africa, Tanganyika’s ANC was radically different from its counterpart. The Tanganyika’s ANC, wanted Tanganyika to be exclusively a domain for blacks. Its leader Mr. Zuberi Mtemvu himself was virulently an anti-white, anti-Asian and against any other non-black even if they were citizens of Tanganyika (Mwakikagile, 2010). The Party’ doctrine of ‘Africa for Africans’, meant only one thing, Africa for black Africans. This doctrine according to Mwakikagile was contrary to the advice by Dr. Martin Luther King who said: ‘We must all learn to live together as brothers (and sisters) or we will all perish together as fools’ (Mwakikagile, 2010).

The newly formed opposition parties (of 1990s) in Tanzania seem to have inherited similar syndrome of internal weaknesses. Teshome (2009) reports that most of the opposition parties in Africa are established around the personalities of individuals, lack internal democracy, suffer from inter-party and intra-party conflicts, have severe shortage of finance, and lack strong base and experience. Their weaknesses also include bad organization and weak connection with the popular constituencies. Arguing in similar lines, Mwakikagile (2010) establishes that, Rev. Christopher Mtikira used the doctrines reminiscent of the African National Congress (ANC) in Tanganyika in the late fifties and early sixties when the party was led by Zuberi Mtemvu. Mtikila the founder and first chairperson of the Democratic Party (DP) also was an anti-whites, anti-Asian and against any other non-blacks. His slogans like ‘wazawa’ (natives) and ‘gabachori’ (non-natives) echoed the sentiments of other racial purists witnessed in the 1950s during the fight for independence such as ‘Africa for Africans’. It is not surprising therefore that Tanganyikans now Tanzania did not trust opposition political parties and Tanzanians continue to distrust them.

The same reasons can be said about the November 1st 1962 Presidential Election where TANU candidate Mwalimu (Teacher ) Julius Nyerere won with more than 98% of votes leaving Mr. Zuberi Mtemvu of ANC with less than 2% of total votes casted (Table 3). Mwalimu Julius Nyerere was a non-racial in his perspective, and this position got him into conflict with his colleagues in his Party and the Government, but maintained his stand.

The 1962 and the pre-independence election results had portrayed an image that Tanganyika had only one powerful political party supported by the majority. It was because of the weaknesses of the opposition parties that the government decided to abolish multipartism and opted for a single party democracy thereafter. However, it is still debatable if really weaknesses of the opposition parties could have been a sufficient reason for their abolition.

The decision to turn Tanganyika into a one-party state was made by the TANU’s National Executive Committee and on the 14th January 1963 this decision was announced by President Nyerere (Carter, 1986). The President was given by the National Executive Committee an authority to appoint a Presidential Commission to consider the changes to the constitutions of the Republic and of the Party that might be necessary to give effect to this decision. The Commission was appointed on 28th January, 1964 and reported on 22nd March, 1965. The Commission had 13 members, two of whom were prominent Europeans and one Asian. The Commission invited written evidence and also took verbal evidence throughout the country. Its deliberations were guided by the terms of two important memoranda drawn up by the President and as a result the final report was deeply influenced by President Nyerere’s approach to the whole subject, an approach which, as it turned out, received widespread support during the course of the verbal evidence.

The Commission laid finally at rest the view that the party should not be a small, elite leadership group and insisted that it should be a mass organisation open to every citizen of Tanzania. This decision finally established the character of TANU as constituting a national movement; indeed the word ‘party’, with its sectional implications, was no longer an appropriate description and the resulting pattern of Government, as Professor Pratt has suggested, ‘was in many ways closer to a no party system than to a one party system (Ibid)’. It is clear from the evidence that this concept fully reflected the mood of the people, who showed no interest at all in entrenching ideologically exclusive elite, but saw the necessity for a single national movement to emphasize and safeguard the unity of the nation.

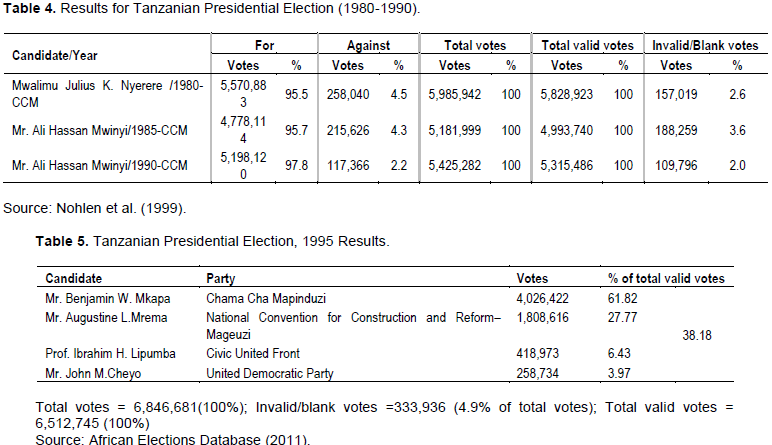

The assumption was that, single party democracy would strengthen nationhood, unity and solidarity among citizens. During single party democracy, there were only one presidential candidate and voters were asked to decide whether they vote for him or against him. The opposition votes in this system ought to have been manifesting itself in a form of ‘against votes’. Reading across the various single party Presidential election results one can note that the against votes did not exceed 5% (Table 4), and most CCM supporters may argue that this suggested a solid trust to the CCM while others may argue it showed lack of alternative. This paper subscribe to the former than the later largely, because, voters were not forced to the ballot box. In all elections during that time CCM came out with a landslide victory of over and above 95%.

CCM is still enjoying the fruits of decisions made by TANU in the 1960s which presented the party as ‘everyone’s party’ and it will continue to benefit for many years to come. Tanzanian opposition has failed to come up with a candidate of their own. During elections opposition leaders will defer their internal nomination until CCM finishes its nomination to wait for anyone who is discontented with CCM decision of not picking him to join their parties. As a result all candidates who seemed to bring some sort of challenges were former CCM leaders. Mr. Augustine Mrema for example joined the National Convention for Construction and Reform–Mageuzi Party and became its presidential candidate in the 1995 Tanzanian Presidential Elections. He became the leading opposition Candidate with 27.77% of the total votes (Table 4). The problem with this methodology is that, parties with little or no screening techniques tend to absorb everyone who appears to support them, in so doing they end up picking candidates whom they don’t know very much and in the end some become reliabilities and sources of internal divisions. Regarding this argument a good example is that of Mr. John Shibuda the former MP of the ‘Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo’, in several occasions he was against his party’s decision.

A closer look at Table 5 reveals that in the 1995 Tanzanian Presidential Election, opposition gathered a total of 38.18% of votes the highest number of votes than in any other elections. This opposition performance was triggered by the fact that it was the first multiparty elections after it was abolished in the 1960s. Some voters who were born in between 1965 and 1992 never saw multiparty system and were excited but slowly that excitement faded out because the opposition parties did not meet their expectations and the number of opposition supporters went on decreasing election after election as it can be witnesses in the subsequent Tables.

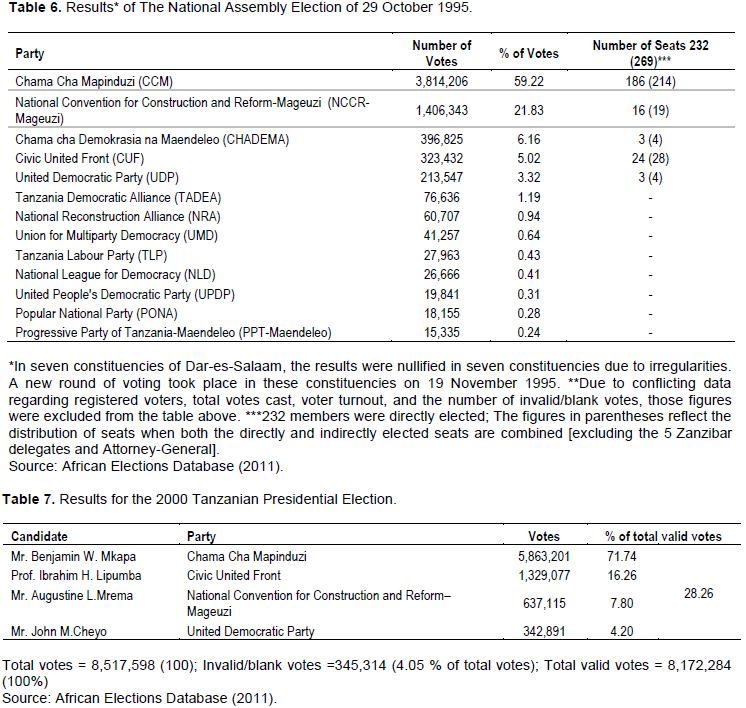

Parliamentary election results in Table 6 show that CCM had majority of the seats in the parliament (186) as compared to opposition (46). During this time the most popular opposition party was the Civic United Front (CUF) with its strong hold in Pemba Zanzibar. CUF got 24 seats all of them from Zanzibar followed by the National Convention for Construction and Reform-Mageuzi (NCCR-Mageuzi) of Mr Augustine Lyatonga Mrema which obtained 16 seats all of them from Tanzania Mainland. Failure for opposition parties to get seats from both sides of the union i.e. Zanzibar and Tanzania Mainland shows that the opposition parties were not accepted by all citizens, they are not ‘nationalistic parties’, hence, voters saw them as ‘ none-unifying’ and therefore they cannot advance ‘nationhood’. The only party which has been getting many seats from both sides of the union during all these elections is CCM. It should be noted here that CCM was formed by a merging of two very strong political parties, Afro-Shiraz Party (ASP) from Zanzibar and the Tanganyika African National Union (TANU) from Tanganyika now Tanzania Mainland. Suffice to say CCM was built on a solid foundation and is still enjoying the fruits of the foundation. Many of these opposition political parties were formed out of ad hoc meeting of friends who did not even know themselves very well. Consequently, internal conflicts and scramble for power were common.

The Tanzanian Presidential Election of the year 2000 witnessed CCM wining again and this time its presidential candidate Mr. Benjamin William Mkapa was competing for his second term in office (Table 7). Contrary to majority’s expectation, the total votes which went to opposition declined by 20% from 38.18 to 28.26 votes. One would expect that, because they were dealing with the same opponent they would have improved their total votes but that wasn’t the case. These election results confirm the general perception of the Tanzanians that, CCM presidential candidates are better in their second terms that in their first terms (with few exceptions). It can be predicted that CCM will win the 2020 elections comfortably regardless who the opposition choose as their candidates. If the opposition can’t learn from their mistakes, they should forget going to state house soon.

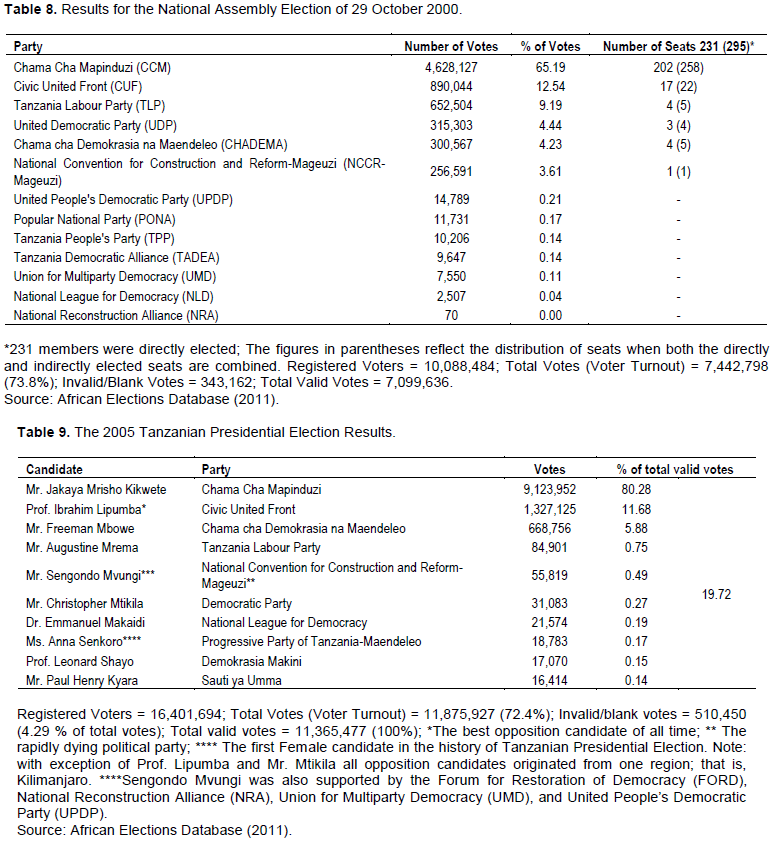

Likewise, CCM won the 29 October 2000 National Assembly Election with majority of seats 202 compared to opposition’s 29 (Table 8). The Civic United Front (CUF) again was the most popular opposition party followed by the Tanzania Labour Party (TLP). Reasons for the failure are almost the same ‘internal conflicts’ and lack of long term vision. For example, the National Convention for Construction and Reform - Mageuzi (NCCR- Mageuzi) was just coming from a serious internal conflict which forced its National Chair Mr. Augustine Mrema and his followers to renounce the party and join the TLP, therefore opposition was divided at a time when unity was highly needed.

The wining story continues for CCM as the losing story for the opposition during the Tanzanian Presidential Election of 2005. During this election, CCM had a new presidential candidate Mr. Jakaya Kikwete, while nearly all opposition parties had the same presidential candidate defeated in the previous elections (Table 9). This was the election where CCM won most comfortably more than any other election since the times of Mwalimu Julius Nyerere and Mr. Ali Hassan Mwinyi (80.28%). This election again witnesses the opposition camp failing to get the candidate they were expecting from CCM. It should be noted here that Chadema had delayed its nomination of the presidential candidate to wait for unsatisfied CCM members to join them. This time it did not work, there were no influential member of CCM who had opted to join the opposition; as a result, the Chadema for example, opted for their youthful chairman Mr. Freeman Mbowe to vie for the position which he lost badly. It was only during this particular election when the opposition for the first time, conceded defeat. Political scientists say, during this election opposition had lost before voting and conceding defeat was not only necessary but more meaningful.

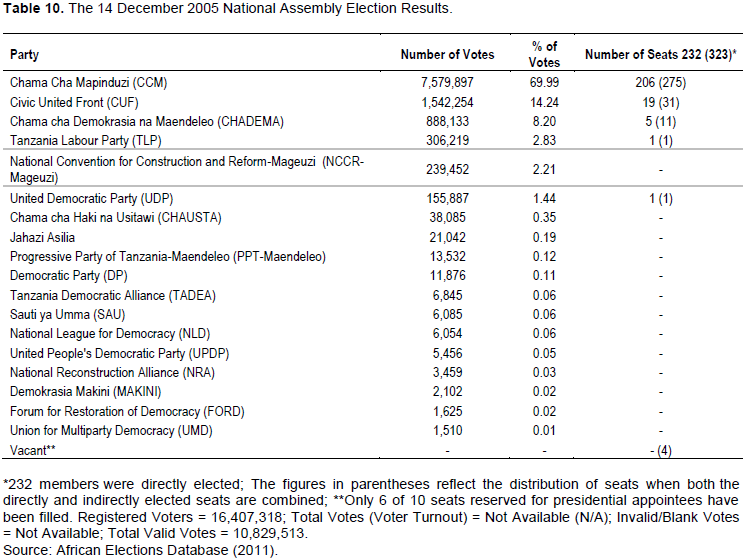

The opposition again lost the December 14 2005 National Assembly Election (Table 10). For many years now Tanzania has been a democratic country which follows principles of democracy. Democracy as system of government has some basic principles, namely: Rule of law, freedom of press, respect for human right, active political participation and active political processes. Other essential features of democracy in the advance femocracies are: ideologically based political parties, internal democracy in party politics, political party supremacy and good governance (Dauda, 2015). It should be noted here that this particular election as for all previous ones was free, fair and democratic. This is why opposition had to concede defeat.

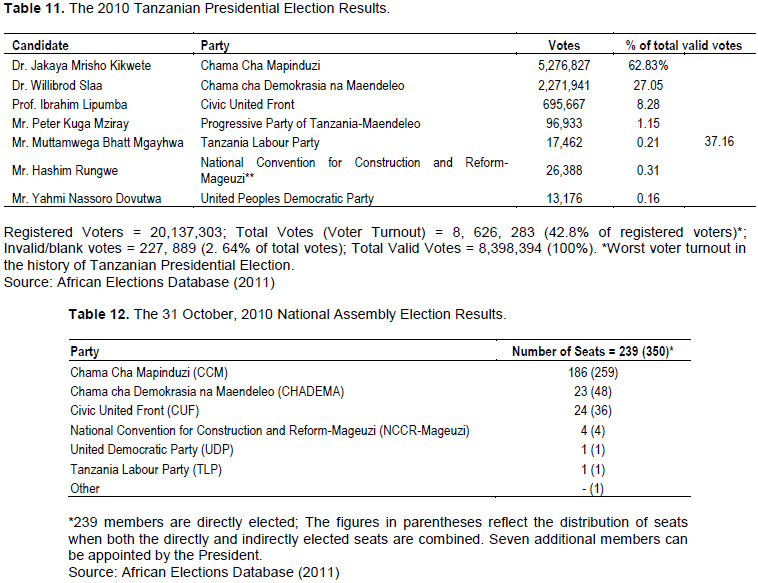

It was not surprising that, opposition lost again during the 2010 Tanzanian Presidential Election (Table 11). It is equally important to note here that only 8,626,283 voters equivalent to 42.8% of total registered voters (20,137,303) voted during this election; where, 227,889 votes (2.64% of total votes) were invalid votes. This was the worst voter turnout in the history of Tanzanian Presidential Election. Even if the discussion on reasons as to why so many voters did not vote is not part of this papers’ subject matter, it is necessary to comment on it. The poor voter turnout could be attributed to lack of voter education which may be a result of limited awareness campaign from both the opposition and CCM. It is also difficult to establish that the low voter turnout benefited CCM than opposition, because even CCM members did not turn out to vote. CCM has more than eight million members countrywide. It is not possible that all voters who turned out were CCM members.

Like the Presidential Election, CCM won also the 31 October, 2010 National Assembly election as widely expected. Ad hoc preparations, internal/inter parties conflicts, lack of unity among and between political parties as well as vague ideologies and policies of the parties resulted to the opposition getting only 53 seats out of 239 available seats (Table 12). The parties therefore do not have clear-cut alternatives to present to the voters, and the programmes are of lesser importance than the personalities who represent the parties and contest elections. Second, only the incumbent party is able to reach down to the voters on a regular basis. The other parties do not have the necessary organisation or resources, and contact therefore becomes sporadic and ad-hoc. Finally, very serious conflicts within the parties threaten both the stability and credibility of the parties and the party system (Magnar, 2000).

The Tanzanian Presidential Election of 2015 confirmed lack of unity among opposition political parties and internal conflicts. This time again the opposition camp failed to come up with a single candidate. Instead they fielded seven candidates to challenge CCM’s Dr. John Pombe Joseph Magufuli. Again, like in 1995 elections, the opposition relied on the former CCM member Mr. Edward Lowasa to take them through of which he did not. Mr. Lowasa came second with 39.97% of total votes (in an election where opposition believed they will win) whereas, CCM’s Magufuli gathered 58.46% of total votes (Table 12). It is important to note here that, prior to this election chadema had expelled three of its very important cadres namely: Mr. Zitto Zuberi Kabwe, Dr. Kitila Mkumbo (Now Prof.) and Mr. Samson Mwigamba. This was a bad move at making, because these cadres went on forming a new political part known as Alliance for Change and Transparency (ACT). ACT was seen by many Tanzanians as the only viable alternative party to CCM which preaches nationhood, peace and unity. As a result, despite it only being few months old it entered into an election and its candidate came third after Dr. Magufuli and Mr. Lowasa by gathering a total of 98,763 votes.

Perhaps the most damaging move for chadema and opposition in general was that of ousting its national Secretary General Dr. Willibrod Slaa in an attempt to attract the former CCM member Mr. Lowasa. In a highly-attended press conference broadcasted live on various television stations across the country Dr Slaa gave details of his decision not to give a nod to his party agreeing to receive Mr Edward Lowassa as the opposition's presidential flag bearer. Dr. Slaa pointed finger to Chadema presidential candidate Mr. Edward Lowassa as being corrupt and therefore unreliable as a leader. Chadema had lost credibility and public trust for accepting former Prime Minister Edward Lowassa who has incessantly been implicated in various corrupt practices (Majaliwa, 2015). He used a number of documented and undocumented examples to illustrate why Mr. Lowassa is tainted, suggesting that with all that 'liability', such a candidate cannot have the moral authority to become president. ‘What has happened in my party is retrogressive, and since I do not agree with the move they have made, I have left Chadema and quit politics generally (ibid). To greater extent any serious analyst would expect the opposition to fail in 2015.

During the 2015 presidential elections the opposition camp gathered a combined 41.52% of the total votes (Table 13) but this percent is expected to go down in 2020 elections because the opposition is not making any meaningful efforts to improve or maintain its votes. Recent polls have indicated that President Dr. John Magufuli’s popularity is increasing drastically countrywide. For instance, the polls which was commissioned by the Mwananchi Communication limited in February 2016 showed that, if elections were to be conducted in February 2016, Dr. John Pombe Joseph Magufuli of CCM will win by 75% whereas the main opposition leader Mr. Edward Ngoyayi Lowasa will lose the elections by scoring only 20% of votes. The polls also revealed that Dr. Magufuli’s popularity among different cohorts is also increasing. He is 75% popular among young people aged 26-35 years, 73% popular among those aged 36-45 years, 79% among rural voters (who are traditionally the majority of voters in Tanzania) and 78% popular among women (Kimboy, 2016). The former works minister is maintaining popularity in all zones, 82% central, 73% Coast, 68% Lake, 78% Northern (traditionally opposition’s strong hold), 78% Southern and 92% Zanzibar (Kimboy, 2016). This might surprise many; just three months after the general election, voters are no longer interested with opposition politics. The mere fact is opposition parties are not performing. They are ‘event based political parties’ and in most circumstances are operating on ‘activist basis’. The sooner they turn and operate as political parties, only then will they realize that it is better for them. Activism politics do not work in Tanzania.

It can be said here that the coalition formed by Chama cha Demokrasia na Maendeleo (Chadema), the Civic United Front; National Convention for Construction and Reform-Mageuzi (NCCR-Mageuzi) and National League for Democracy (NLD) was the coalition of the scrawny and its failure signifies a huge lack of faith among the general public on the opposition parties. Likewise, the 2015 elections witnessed the opposition parties losing their strong holds in Kigoma, Mwanza Urban and Musoma Urban, with key opposition figures losing in the process. In the list there is Mr. Ezekia Dibogo Wenje (Nyamagana constituency), Mr. Vincent Josephat Kiboko Nyerere (Musoma Urban constituency) and Mr. David Zacharia Kafulila (Kigoma South constituency). Table 14 reveals more information regarding the Tanzania’s 2015 National Assembly Elections results.