ABSTRACT

This article examines the pattern of popular trust in public and political institutions in Ethiopia. The analysis employs individual-level survey data and uses ordinary least square regression to analyze the relative explanatory power of independent variables for variations in citizens’ institutional trust. The results demonstrate that citizens’ trust in public institutions varies extensively from one public and political institution to another. This article argues that institutional performance is crucial factor in explaining the source of citizens generalized trust in Ethiopia. This article concluded that citizens’ popular trust in Ethiopia is a function of their expectation of the quality of the services offered, as well as their evaluations of government’s efforts to provide services in a fair and equitable manner.

Key words: Citizens trust, public and political institutions, Ethiopia.

The development of public and political institution-building in Ethiopia was not a linear process. As a result of changes in successive political leaderships in Ethiopia, institutional changes have been very common. In the process the institutional memory has been lost, and institutionalization has always been interrupted as a result of shifts in the power relationships between actors. Time and again, ‘institutions have been overcast by political control’ (Bahru, 2000: 21). Institutions ‘had not been allowed to function with the freedom that is so essential to their vitality’ (ibid.). The three successive regimes that came to power in Ethiopia tried to recast the institutions according to their political interests and dispensation. In their institutional-building schemes, what they have followed in differing degrees is a top-down approach.

The path of institutionalization development that took place in Ethiopia subsequently categorized into three eras: ‘the period of institution-building (1941-1974), the period of stress (1974-1991), and the period of restructuring (1991 to the present)’ (ibid.). As a part of the third era of restructuring, the present public and political institutions in Ethiopia with their current formal, legal and institutional arrangements emerged in the post 1991 period (Kassahun, 2009). The main architect of these institutions was the incumbent political party, Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF). As a formal institution, the reorganized institutions ‘conform to international standards and appear to be suitable for nation-building’ (Hovde, 1994: 131). However, a typical defining picture that one can observe regarding the EPRDF restructured institutional changes has been the hallmark of institutional weakness in the key governance institutions of the state. The civil service institutions in Ethiopia have manifested a comparable institutional and capacity weakness (Berhanu and Vogel, 2006).

When it comes to relations between citizens and public and political institutions in Ethiopia, the mere existence of these institutions per se is not a sufficient proof that they enjoy the political trust of citizens. In this regard, the important question that needs to be answered is whether or not existing public and political institutions that have emerged in the post 1991 period are adequate enough for promoting trust in making political relations work smoothly (Stokes, 2006). In lieu of pervasive institutional weakness in public and political institutions, what kind of trust/distrust relationships have been existing in Ethiopia between citizens and these institutions? What makes Ethiopian citizens trust or distrust these institutions? What is the prevailing pattern of trust or skepticism in governing institutions of the country? And, what factors can explain this pattern? In order to answer these and other related questions, this study therefore aims to identify and critically examine the existing pattern of trust in public and political institutions in Ethiopia.

Problem statement

Currently, in Ethiopia, most of the public and political ‘institutions and the laws related to good governance face challenges, such as one-party dominated politics, as exhibited in the legislature; inadequate result in decentralization efforts; government controlled media; underdeveloped civil society lacking conducive environment to flourish; unimpressive record of human rights protection by the government, and lack of transparency. Inadequate administrative capacity of the government is also manifested in poor human resource planning, implementation, recording and supervision, corruption, poor financial management, and weak coordination and perpetual reorganization of institutions’ (Dejene and Yigremew, 2009: 144). Alemayehu (2001: 5) also indicated that ‘corruption is perceived to be a growing and gnawing problem in the Ethiopian civil service. Traditional value of loyalty, honesty, obedience and respect for authority are giving way for breach of trust and dishonesty’. On top of all these impediments of the public sector, Kpundeh and Khadiagala (2008: 2)’s empirical research on information access, governance and service delivery in key sectors in Ethiopia and Kenya reports that ‘service delivery is hampered by social capital constraints conceptualized as the trust deficit, where there is a wide attitudinal gulf between service providers and recipients of the services. Lack of trust between the citizenry and governments is not only inextricably linked to the governance deficit, but it also reflects the legacy of state abdication of service delivery roles in the past’.

Next to the public service lack of trust, the empirical literatures available on the major political institutions also emphasize the deficiency and the lack of independence of these institutions. Concerning Ethiopian parliament, Dessalegn (2008: 154) contends that it ‘is not a ‘debating forum’ in the constructive sense of the term. Mulugeta and Cloete (2006), Kassahun (2005: 181)’s works conclude that ‘Ethiopia parliament is largely a legitimizing agent of the status quo, serving the dominant party (EPRDF) operating under the shadow of a dominant executive. In the circumstances, parliament is an organ of government rather than an instrument of governance influencing and changing the course of public policy’. The judiciary, as the other state institution, is also identified as lacking institutional independence, and that it has been working under the shadow of the executive (Adem, 2012; Assefa, 2011). Apparently, as a part of African states having a dearth of most crucial trusts promoting institutions, Ethiopia ‘shows all the characteristics of pervasively low-trust societies’ (Berman, 2004:50).

In the context of the above problem statement, why trust in public and political institutions is so important in Ethiopia? Understanding citizens’ trust is especially important because it is not only central to understanding of the current political dispensation (Iroghama, 2012), but also it is significant in understanding how the existing public institutions in Ethiopia shape the attitude and behavior of citizens. When citizens think and act politically; as assumed by new institutionalism, they ‘take their cues from the structure of rules, procedures, and customs prevailing in the polity in which they live’ (Bratton, 2010: 103). As such, political institutions provide a revealing aperture through which to view-and to explain-regularities in public opinion and mass participation (ibid.). Examining Ethiopian citizens’ perception of the current political dispensation is also essential to understand their readiness to support the political institutions of the state (Bratton et al., 2005). This is because lack of citizens’ institutional ‘trust can lead to erosion of public confidence and loss of legitimacy of governments. Consequently, distrust or lack of trust, can pose serious challenge to working of governments’ (Iroghama, 2012: 327).

Therefore, taking the above problem statement as a background, most importantly, this paper not only examines the pattern of trust/distrust in public and political institutions in Ethiopia, it also attempts to explain citizens’ trust using the theories of institutional trust. The paper is structured into four parts. The first part is set out to discuss the two broad theoretical approaches for understanding the origin of institutional trust in two subsections. The second part addresses the methodology of the paper. The third part presents the existing pattern of public and political institutional trust in Ethiopia. The fourth part provides the empirical analyses of the explanatory variables of institutional trust in Ethiopia. It also offers the discussion of the empirically produced findings in light the theoretical argument of cultural and institutional theories of trust. Finally, the paper provides conclusion.

THEORETICAL UNDERPINNINGS

The starting point to identify theoretical framework of this article is to pinpoint the theory that attempts to explain trust. However, ‘for all that has been written about it in recent years, there is no general theory of trust’ (Delhey and Newton, 312: 2005); rather, there are theoretical approaches which attempt to explain the origins and determinants of trust. Theoretically, this study is based on the two contending theories of the origin of institutional trust. These schools of thought are namely theories of cultural values and performance/institutional theories. These theories are ‘often characterized as incompatible, although they both share the fundamental assumption that trust is learned and linked at some level to direct experience’ (Schoon and Cheng, 2011: 620). These theories attempt to provide their own version of ‘explanation for the origin of trust and offer very different perspectives on the prospects for developing sufficient trust for democratic institutions to survive and function effectively’ (Mishler and Rose, 2001: 31). Contrastingly, ‘the two theories differ regarding their assumption about when most learning is likely to occur. Cultural theories emphasize the importance of early experiences with little change later on, whereas institutional theories stress the role of more proximate and contemporary experiences with institutions. Institutional theories acknowledge that culture can condition attitudes toward institutions, as can the past performance of institutions, but neither culture nor past performance is deterministic’ (Schoon and Cheng, 2011: 620). In terms of focus, cultural theorists emphasize on the role of cultural values, whereas performance oriented theories focus on how political trust relates to public evaluations of government performance (Norris, 1999).

Dependent variable

For the purpose of this paper, following Breen and Gillanders (2013), Kouv (2011), Kuenzi (2008) and Lavallée et al. (2008), the dependent variable is measured by an index of institutional trust that incorporates questions on the degree of institutional trust that a citizen has in key political and public institutions. This trust index reflects the measure of the aggregate of the degree of trust and confidence in six key institutions: parliament, government, police, courts, political parties and civil service in Ethiopia. To create the trust index, the range of citizens’ responses for InterAfrica Group (IAG) survey for these key particular institutions was recorded in a reversed manner and each of the responses is ‘not at

all’, ‘not very much’, ‘quite a lot’ and ‘a great deal’ to which is attached values 0-3 respectively. During the recording, it is dropped the ‘don’t know’ response of IAG survey question for public and political institutions. It is argued that the ‘don’t know’ response implies that the respondents had ambivalences or do not have clear cut image whether they would trust or not these institutions. Thus, the dependent variable of this study is ordinal in its nature and reflects the measure of the aggregate of the degree of trust and confidence in these six public and political institutions in Ethiopia.

Independent variables

In a growing body of literature, the two approaches presented above have received different degrees of empirical support in the origin of citizens’ institutional trust (Wong et al., 2011). However, ‘which approach (institutional or cultural) is more powerful, so far, not totally clear’ (ibid: 267). As a part of these two approaches, there are many factors or determinants that explain variations in institutional trust (Dyrstad and Listhaug, 2013). Accordingly, to address the main research objectives of this study that guide the empirical inquiry, the study focused on four independent variables or determinants used to explain citizens’ institutional trust in Ethiopia. In view of that, from the available literatures, the four group of independent variables of this paper are demographic background (age, ethnicity, rural and urban residency, gender, and level of education); political engagement (membership in political party, citizen’s interest in politics, and, civil society activism); understanding of democracy (interpretation of democracy, civil rights and freedom, rejection of autocracy, and media exposure); and institutional performance (quality of life and socioeconomic well-being, political performance index, economic performance, level of corruption and government’s strategy in fighting corruption). Accordingly, the following hypotheses were derived from the independent variables to guide this paper:

(i) H1a: Younger citizens (18-35) are less likely to trust in public institutions than elderly citizens (36-61+).

H1b: Citizen belongs to an ethnic majority, may find that public institutions quite trustworthy because they perceive their interests are properly represented by it, and is likely to express higher level of trust than a member of ethnic minority who feel the other way round.

H1c: Urban dwellers citizen displays higher level of trust than citizen living in rural area.

H1d: Ethiopian women are less likely to have higher level of trust in public and political institutions than men.

H1e: The higher educated citizens, the lower their trust in public and political institutions.

(ii) H2a: Citizens’ membership in political party enhances their generalized trust and more generalized trust may lead to more trust in political institutions.

H2b: Citizens with higher cognitive mobilization (that is, greater interest in politics) will have a better understanding of the existing democratic system, and will therefore be more prone to trust its institutions.

H2c: Citizens with active membership in various socio-political activities are likely to have high trust in institutions.

(iii) H3a: The more an individual attach positive value to democracy, the stronger his or her trust in political institutions.

H3b: The more civil rights and freedom of citizens are guaranteed, the higher the level of trust they may have.

H3c: The stronger an individual rejects autocracy, the higher his/her support for democracy, and hence the stronger his/her trust in political institutions.

H3d: The more media freedom in a country, the lower citizen’s trust in public and political institutions.

(iv) H4a: The better an individual perceives the quality of life and socioeconomic well-being conditions to be, the stronger his or her trust in political institutions.

H4b: The better an individual perceives the political performance to function, the stronger his/her trust in political institutions.

H4c: The greater an individual’s satisfaction with the national economy, the stronger his/her trust in political institutions.

H4d: The higher an individual perceives the level of corruption in state institutions to work, the lower his or her trust in the institutions.

H4e: The more positive citizens’ evaluation of the government fight against corruption to be, the greater is their trust in state institutions.

The methodology of this paper makes use of quantitative research design. The quantitative data of this study is based on the IAG cross-regional survey 2007. The justification for adopting this method was first deemed appropriate for realizing the objective of the study. Secondly since in the Ethiopian context, the level of trust may differ from one institution to another, the use of the quantitative method provides the opportunity to secure statistical generalizations that would further help to make comparisons across public and political institutions for their level of trust/distrust they enjoy. Bratton et al., 2005: 65) argue ‘trust in political institutions is…particularly appropriate to address through surveys of public opinion’. The main reason why this paper based on the data came from IAG survey is because ‘it provides a rich set of explanatory variables to examine varying levels of trust across political institutions’ (Lyons, 2013: 348). Second, it was the only avaliable dataset of public opnion survey of key public and political instituions in Ethiopia. It was collected by trained interviewers via computer assisted face-to-face interviews. At the time of field data collection, 3 field coordinators, 8 back checkers, 67 supervisors and 157 interviewers participated in the IAG survey. In addition to this, back-checkers and supervisors were having minimum Bachelor degree holders in statistics, economics or related social science studies and have at least two or more years of experience in survey supervision, planning and coordination (IAG, 2008) (Table 1).

Moreover, the IAG survey data is an extensive public perception survey and it was essentially aimed at measuring and understanding the public view on a number of socio-economic and political issues, including support and approval of government policies and performance. As a result of this survey, information on a number of public issues, based on the views, opinions and perceptions expressed by the general public have been established (IAG, 2008). The IAG survey also captures views on whether citizens feel that overall corruption levels have increased or decreased in the public institutions which suffice the aim of the this paper.

Citizens were also asked whether they are satisfied or not with the government’s strategy in fighting corruption in Ethiopia. As far as the search for other survey is concerned, this is the only available extensive survey so far pertinent to institutional trust in Ethiopia. Because of the dearth of other surveys on this matter, it is considered as a base line survey for institutional trust in Ethiopia. The second reason to use this survey is because it is completely an institutional performance perception survey. As theories of institutional trust indicates the level of institutional performance and corruptions have an impact on the level of citizens’ trust/distrust. Thus, for the purpose of examining institutional trust in Ethiopia, this survey is indispensable to provide the empirical data for identifying the existing pattern of citizens’ institutional trust. In this regard, let us see first the socio-demographic distribution of respondents compared with the Population Census Data of 2007 carried out by the Central Statistics Agency of Ethiopia (CSA).

Table 1 above compares the data collected from the respondent vis-à-vis the data from Population Census Data for the purpose of authenticity of the results. In terms of reflecting socio-demography distributions of the respondents, the sample is equally split between males and females. The survey data managed to capture significant differences of 7% plus and minus for urban and rural respondents respectively compared to the Population Census Data. With respect to age groups, IAG survey data collected from those respondents aged 18 years and above and categorically respondents were grouped into four age cohorts: 18-30 years, 31-40 years, 41-50 years, and 51 and above years, whereas the Population Census Data includes all age categories. The IAG survey respondent includes respondents from all regions in Ethiopia. As shown in Table 2 it has coverage of rural (79%) and urban (21%) areas. In this survey, the ratio of rural residents is much higher than that of urban dwellers because the majority of Ethiopian citizens, 86% are currently living in rural areas. Data in the population and the sample distribution are quite similar without huge discrepancies.

Finally, Ordinary Least Square regression technique (OLS) analysis model was used to test the various hypotheses indicated in section two of this paper. Multivariate model of regression analysis was used to find out the relative importance of the four independent variables of this study (demographic variables, political engagement, understanding of democracy, and institutional performance) for variations in public institutional trust index. Hence, the multiple regression analysis shows whether a statistical association exists between a dependent variable and a range of independent variables. It also shows how strong this relationship is and, therefore, the extent to which the independent variable that has been identified has an effect on the citizens’ trust public and political institutions in Ethiopia. Here, the OLS regression analysis is also used to estimate the effect of the independent variable on the index of institutional trust in Ethiopia. In the OLS analysis, standardized beta coefficients were used. In order to make valid OLS regression analysis, the OLS assumption of multicollinearlity aspect of the independent variables was checked first, that will be discussed further in section four of this paper.

1. The recruitment criteria for interviewers were college diploma or high school completion certificate with at least two years of data collecting experience. Recruitment of the field survey staff was conducted with the assistance of the National Central Statistical Authority of Ethiopia (ibid.).

PATTERN OF INSTITUTIONAL TRUST

The main purpose of this section is to examine the patterns of citizens’ level of trust and confidence in the public and political institutions in Ethiopia. Organizationally, this section is divided into three sections. The first section begins with the examination of the patterns of popular institutional trust in Ethiopia. The second subsection compares the pattern of institutional trust in Ethiopia with that of other Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The third sub section provides the discussion and findings. Citizens’ general attitude towards the public institutions is an important issue since it contributes to the understanding of what kind of image and levels of trust they have of key governance institutions in their respective country (Bouckaert et al., 2005). By and large, their ‘opinion towards government in general and specific services has often been identified as an important indicator of the effectiveness and responsiveness of the overall political system’ (Pino, 2005: 512-513). To put it simply, citizens’ trust in governing institutions of the political system is also considered as ‘the cornerstone for the maintenance of democratic regimes and for day-to-day governance’ of the society (Chang, 2013: 75). In this regard, ‘the level of trust citizens have in their political institutions is an intuitive measure of the congruence between their political preferences and the outputs of the representative political institutions’ (Christine et al., 2012: 3) of the state. However, in administrative culture research the relevance of citizens’ trust in public institutions has received relatively little attention in the last one decade (Bouckaert et al., 2005).

Contemporarily, taking citizens as the object of study, various academic studies have been conducted to assess how citizens perceive public and political institutions to work in relation to their demands. To understand citizens’ popular attitude, public opinion surveys are frequently used in order to describe and analyze their attitude about government performance as well as their trust in state institutions (Bratton et al., 2005; Bratton, 2013). In this regard, a well-designed public opinion survey can capture patterns in citizens’ institutional trust ‘across different geographic regions or social groups’ (ibid, 2013: 1). Accordingly, to tap into Ethiopian citizens’ attitudes towards political institutions, as indicated in the previous section, this paper employs public opinion data of InterAfrica Group (IAG) survey of 2007.

Pattern of institutional trust in Ethiopia

The task of this section is to examine the level of trust of citizens in various public institutions. To gauge whether Ethiopian citizens hold confidence and trust in public and political institutions, the respondents were asked how much trust they have in twelve institutions indicated in Table 2. This question is a central theme since the dependent variable analysis of this study is about citizens’ trust in public and political institutions. For the data reported in Table 2, ‘a great deal of trust’ and ‘quite a lot of trust’ responses are added together. Likewise, ‘not so much trust’ and ‘not at all’ responses are also added together and reported as a single figure. For the purpose of simplicity, it is rounded-off the percentage of decimal place into the nearest whole number. The results displayed in Table 2 show the level of trust and confidence in twelve public and political institutions in Ethiopia and institutions have been ranked in descending order by the level of trust from the highest at the top (religious organizations) to lowest trust at the bottom (labour unions).

Looking at the result of the survey in the above table, we can see that the level of trust varies considerably among the types of public and political institutions. As the above ranking indicates, some institutions attract comparatively high level of citizens’ trust while others enjoy low level of trust. Among all twelve institutions, religious organizations, national government, police and courts are highly trusted. Out of these three, religious organizations are the most trusted institutions, with more than 90% of the population claiming to trust these institutions ‘a great deal’ or ‘quite a lot’. Moderately, the relative ranking of value-based organizations (women, NGO’s and environmental) is much the same and they enjoy the intermediate position of confidence and trust of citizens. As indicated above, more than 51% of the population expressed their trust to women’s organizations; while 49% of the population indicated trusting NGOs and almost equal percentage of the population (48%) said they have confidence in environmental organizations.

The government media (electronic and print) is a less popular national institution in Ethiopia. It is only 51% of the research population said they had trust on it. Here, the government media is treated as an object in which citizens have confidence in it rather than a trust-building promoting channel that supplies information (how institutions fulfill their job) about governing institutions. In general, government media plays a potentially important role in shaping of the public trust in governing institutions. This could be done by ‘amassing and shaping public opinion, which in turn promotes demands for more effective management by the government’ (Svedin, 2012: 102). However, in the case of Ethiopia, ‘the state monopoly of disseminating information continues to restrict Ethiopian citizens’ ability to make informal decisions’ (Berhane, 2002: 645). And, even, ‘many journalists have a pessimistic view of audience confidence in the state media’ (Skjerdal, 2010: 114). The government media criticized for honest reporting of social and political issues in the country. Most of the time, it either deliberately ignore or distort the information they disseminate. It has been working as a propaganda instrument of the incumbent government, and now and then providing rosy picture of performance of public institutions of the country.

Compared to the above value-based organizations, the case of citizens’ confidence and trust in the civil service is fairly high and 59% of the population perceived it as trustworthy institution. In contrast to this, representative institutions: parliament, political parties and labour unions secured the low level of trust from the population. Among these institutions, relatively the least trustworthy institutions appear to be labour unions: only the trust of a quarter of the respondents. It is considered the high percentage (51%) of ‘don’t know’ answer to labour unions as a reflection of the lower saliency of this institution when compared with the above public and political institutions in the country (Listhaug and Ringdal, 2007). Why does trade union enjoy a lower level of trust in context with other key institutions in Ethiopia? The principal reason for this is their restricted role in workplace collective bargaining. Other than advancing the economic rights of their members, the voice of trade unions has not been loud enough in addressing political demands concerning the public in general. They lack a clear strategy for aligning themselves to the other sectors of the society.

Of all the governing institutions, comparatively the national government received the highest institutional confidence, police and courts are perceived as the second and the third trustworthy institutions in the eyes of the public. The national government is the second most trusted institution next to religious organization and attracted 83% of level of confidence and trust from the target population. In terms of the public’s confidence and trust in governing institutions, police as an agency secured more than 68% of public trust. The overall confidence displayed for the courts is 65%, and it is slightly lower than that for the police but still places the courts at the fourth highest overall trusted public institution that the population indicated.

It is argued that parliament is ‘a key institution in democracy and the main arena for inter-party politics’ (Dyrstad and Listhaug, 2013: 59). And particularly, ‘citizens’ confidence in parliament is an important indicator for how democracy works in society’ (ibid.). As far as confidence in parliament is concerned, it is striking that parliament, the main representative institution linking citizens and the state enjoys a low level of trust among the public (Newton and Norris, 1999). Looking at the results of the pattern of institutional trust in the above table, it is clear that the low level of trust in national parliament in Ethiopia needs explanation. Diamond (2007: 20) indicates that the ‘most important role for parliament in a campaign to rebuild trust in government is to become an advocate for and legislative implementer of the institutional changes necessary for truly serious government accountability’. The fact that national parliament enjoys low level of trust from the public has been explained by referring to its objective problem in the way it functions (Rolef, 2006). In line with this, as indicated by the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation (BTI) Index report (2012: 13), the parliament in Ethiopia has no real ability to check the executive or to represent the hopes, expectations and criticisms of the public’. The low level of trust in parliament emerges from its incapacity to fulfill the expected representative functions vested upon it.

The citizens do not trust the Ethiopian parliament because ‘the role of Ethiopian parliament in monitoring and implementing laws and polices is either totally absent or reliable at best’ (Kassahun, 2005: 175). On the whole, ‘Ethiopian parliament is largely a legitimizing agent of the status quo, serving the dominant party (EPRDF) operating under the shadow of a dominant executive’ (ibid., p. 181). The national parliament in Ethiopia is ‘always approving the executive’s plans and reports swiftly without meaningful discussions and scrutiny. This is in line with most Sub-Saharan African countries parliamentary performance with regard to ‘enacting laws, debating national issues, checking the activities of the government and in general promoting the welfare of the people; these duties and obligations are rarely performed with efficiency and effectiveness in many African parliaments’ (UNECA, 2005: 127).

As indicated above, one troubling finding is that the degree of public trust in political parties. This is because these institutions are indispensable to ‘any liberal democracy since they perform critical functions such as aggregating and channeling citizens’ interests and demands, and organizing competition for public office’ (Mainwaring and Scully, 1995). However, internationally, political parties are among the least trusted institutions (Dalton and Weldon, 2005). In this regard, the level of Ethiopian trust in political parties is following a similar trend. A possible explanation of low level of trust in political parties ‘could be attributable to politics of patronage, which is more effectively dispensed to the public or targeted clients by ruling parties; and in turn the weakening and fragmentation of opposition parties, which also often lack effective strategies for presenting viable alternative policy frameworks to ruling parties’ (Matlosa, 2006: 6). In connection to this, in Sub Saharan Africa, the least trustworthy institutions appear to be the opposition political parties (Lavallée et al., 2008: 4). This is particularly true in Ethiopia too: opposition political parties seem to have low level of trust. What may help to explain the negative sentiment towards political parties are their structural weakness, particularly their low level of institutionalization, their sheer number, their lack of clear differentiation, their low level of membership, absence of internal democracy, high level of fragmentation and organizational instability. Like their African counterparts, political parties in Ethiopia are charcterized by their failure ‘to provide an institutionalized basis from which society can hold governments or elected representatives to account. Many parties are more distinctive in ethnic, religious or regional terms than in ideological ones. A large gulf exists between party elites and society, between leaders and party members or supporters’ (Burnell, 2004: 7).

One interesting finding shown in the above table is the fact that religious organizations typically attract high levels of confidence of citizens than key governance institutions do in Ethiopia. One reason for this could be that citizens feel a sense of ownership of them, and feel that these organizations are responsive to their priorities. Religious institutions are inclusive and easily accessible, and there is friendly and amicable atmosphere in them. Those who run these institutions are also more welcoming. In Ethiopia context, religious institutions are part of citizens’ personal identity, the foundation of their sense of community, and the basis of their hope, and hence, citizens trust religious institutions and their leaders, and also respect religious norms and values (Nishimuko, 2008). The other puzzle is what explains ‘don’t know’ respondents. It is speculated that the interpretation of ‘don’t know’ response could be that citizens belong to this group do not have a clear picture (or scientific knowledge) in their mind of the relevant institutions when they filled out the survey questionnaires. Thus, it is considered ‘don’t know’ responses as missing data and these missing data were excluded from further analysis.

Comparing the generalized trust between Ethiopia and that of SSA

As the above two sections examined, the pattern and institutional trust dimensions in Ethiopia, consequently, one might reasonably ask whether the generalized trust in political institutions of the country is different from elsewhere in Africa. In order to see whether the common trust in governing institutions in Ethiopia is following the same level or whether it deviates from that of Sub Saharan Africa (SSA) countries, it is used the Afrobarometer data of the third round of surveys which was conducted during March 2005 and March 2006. Particularly, this round of surveys was selected because of the near similarity of the time period in question between this round of surveys and that of the IAG survey data. Comparison of generalized trust between Ethiopia and SSA countries must be carefully qualified. One key limitation of such comparative survey data is the difference of number of items (6 versus 7 institutions) constitutes institutional trust index in Ethiopia and SSA respectively. Institutional trust index for Ethiopia is the sum of six items (parliament, government, political parties, civil service, police, and courts) while that for Afrobarometer countries is the sum of seven (parliament, local government, the ruling Party, opposition political parties, the army, the police, and courts of law). In order to reduce such a limitation to the validity, therefore, this section mainly focuses on comparison of generalized trust in political institutions between Ethiopia and SSA rather than the comparison of the relative ordering of public trust in political institutions across the region.

Table 3 shows some interesting cross-country differences of generalized trust among SSA. It presents the means value on generalized trust for 18 countries. The countries are organized by regions and Ethiopia is printed bold in order for easy identification. There are large differences in common trust in governing institutions among Africa countries as the mean score range from 16-17 to around 7. The table indicates that the level of generalized institutional trust ranges from higher in Tanzania where the majority of citizens trust public institutions, to lower in some SSA states (Zambia, Zimbabwe and Nigeria) in a descending order. Within the context of the Horn of Africa sub region, Ethiopia is ranked the second following Tanzania. Compared to Kenya and Uganda, the generalized trust in Ethiopia is a little bit higher than the former and more or less analogous to the latter. Among these countries in this sub region, Tanzania is not only the clear leader in generalized trust, but also the top in ranking across SSA in the region.

As compared to countries in Southern Africa sub region, only Mozambique and Malawi have the highest generalized institutional trust than Ethiopia. In the same sub region, compared to South Africa, Botswana, Lesotho, Namibia, Madagascar, Zambia and Zimbabwe (in a descending order), Ethiopian political institutions enjoyed moderately higher generalized trust. With respect to West Africa sub region, Ethiopia comes in number two next to Senegal. Ghana, and Cape Verde and Benin are ranking third, fourth and fifth respectively. In this region as well as across the continent, Nigeria (6.06) is at the last place and is indeed below regional average. As compared to Ethiopia, the generalized trust gap registered between Ethiopians vis-à-vis Nigerians is significant, and the latter exhibited 7.85 mean score points behind generalized institutional trust in Ethiopia. The comparison of the descriptive statistics of Ethiopia and that of above eighteen African countries reveals that the generalized institutional trust in Ethiopia does not deviate from the rest of SSA.

Therefore, it is possible to conclude that generalized institutional trust in Ethiopia is not significantly different from that observed elsewhere in SSA sub region. In this regard, even if Ethiopia was not included in the third Afrobarometer round surveys, the IAG survey shows that the mean score of common trust in political institution in Ethiopia corresponds with that of SSA countries’ generalized trust. What is clear is that institutional trust index in Ethiopia matches with that observed elsewhere in African continent; however, the absolute mean values recorded may be different. Nevertheless, this simple regional analysis does not allow us to explain the variation of institutional trust among African countries at individual-level.

This section was set out to assess the pattern of citizens’ trust in public and political institutions. More explicitly, there are three important findings of this subsection. The first finding implies that political trust in different institutions differs substantially among the types of public and political institutions in Ethiopia. Some institutions attract comparatively high level of citizens’ trust while others enjoy low level of trust. The study revealed that trust is high for religious organizations and the national government which attract more than 83% of the respondents. The police, the courts and the civil service were the less popular institutions with the proportions of trustors ranging between 69-59%. The groups of institutions attracted citizens moderate level of trust were civil service, women, government media, NGOs, and environmental organizations attracting between 52-48% of the proportion of trustors. The three institutions that were rated less positively appeared to be parliament, political parties and labor unions. The percentage of respondents claiming that they trust these institutions ranged from 41-30%. In a general sense, these findings suggest that citizens’ trust in public and political institutions in Ethiopia is much closer to implementing institutions than representational once.

The second core finding of this paper reveals that the level of the stock of public and political institutional trust in Ethiopia is above average and the overall trust index mean is equated to 13.91. This is an index of generalized trust where six governance institutions (national government, parliament, the courts, police and civil service) were added together. It is equal to the average of the evaluations given for each key institution of governance. This finding was compared with those of SSA countries that shared a similar context. One would expect that this pattern of generalized institutional trust would hold the same or differ for other African countries too. In a comparative perspective, the third finding of this chapter indicates that the generalized institutional trust in Ethiopia is similar to that elsewhere in some SSA countries.

Why does this generalized trust of political institutions in Ethiopia’s authoritarian system enjoy similar trust pattern with related institutions in SSA? As indicated in the introduction section of this paper, the existing core institutions of governance are characterized by institutional weakness and lack of independence, miss appropriation of public funds, pervasive corruption, poor accountability and transparency structure, dominance of one party politics, inadequate decentralization efforts, government controlled media, underdeveloped civil society, and unimpressive record of human rights protection, etc. The explanation for the contradiction between the picture painted by the professional literatures and the perception provided by citizens in IAG survey associated with the regime’s control over information contributes to this result (Shi, 2001). To put it differently, the government controlled mobilization process in Ethiopia seems to be working as a mechanism influencing citizens’ institutional trust for its authoritarian system of governance.

The mobilization process mentioned above refers to the massive influence of government-controlled political propaganda and pattern of repression in today’s Ethiopia (Yang and Tang, 2010). Particularly, via repression measures aimed at restricting freedom of expression and association and access to information, the authoritarian government in Ethiopia covertly created a siege mentality on the part of many journalist to opt for self-censorship, avoiding topics deemed politically sensitive (HRW, 2014). On top of this, directives ‘making printing presses liable for the content of their publications and radio and television stations are either state-run or minimize criticisms of government policy in order to be able to operate’ (ibid: 12-13) have been passed. By doing so, the regime limits citizens’ access to alternative source of information and at the same time, the government controlled media positively propagated the regime’s performance on daily basis in order to influence and promote institutional trust for the core governing institutions of the country.

Determinants of institutional trust in Ethiopia

This section turns to an individual-level analysis of the determinants of institutional trust in Ethiopia. The main purpose of this section is to present the empirical results of the analysis of the determinants of institutional trust and to discuss the findings of this study. This section examines the relative explanatory power of the different independent variables for variations in public and political trust in Ethiopia. It also analyses the results of ordinary lease square (OLS) regression of the five models that are developed to test the general hypotheses and their expected influences on institutional trust. In doing so, various statistical analyses are carried out to test the robustness of these models. The first part of this section chapter provides descriptive statistics of the main variables used in the regression model. The second section checks whether or not the problems of multicollinearlity exist among the independent variables. By fulfilling the multicollinearlity diagnosis, the third section presents the empirical results of the five models tested to explain variation in institutional trust. This section is subject to theory-driven relationship to empirically test the various hypotheses of this study by employing multivariate regression analysis using ordinary least squares technique. The final section closes with the discussion of the findings.

Descriptive statistics of dependent and independent variables

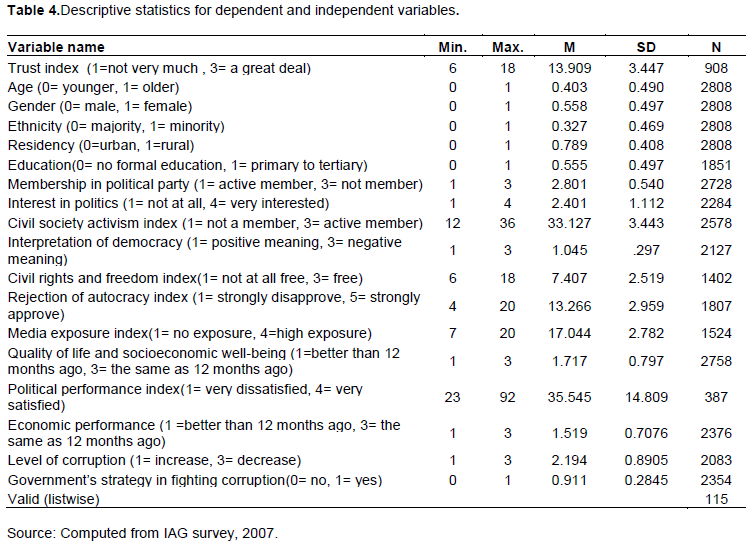

This section presents the descriptive statistics of each of the variables included in OLS regression analysis of this study. Table 4 reports the summary descriptive statistics of dependent and explanatory variables in the regression analysis by indicating its name, number of respondents, the minimum and maximum values and the mean and standard deviation. As shown in the table below, there was a significant reduction in the valid number of observation as compared to the total population of the study. Specifically, the valid number of observation was very low (N= 115) including all the 17 variables listed in OLS regression.

As can be seen from the above table, there were significant variations among the measures of variables in the sample population. Particularly, political performance ranges from a minimum of 23 to a maximum of 92 with a mean of 35.545. Such a wide range of values indicates how the citizens judge the delivery of services in 23 service areas. Moreover, there are also large variations in civil society activism index, rejection of authority index, media exposure index, civil right and freedom index and in the trust index measure.

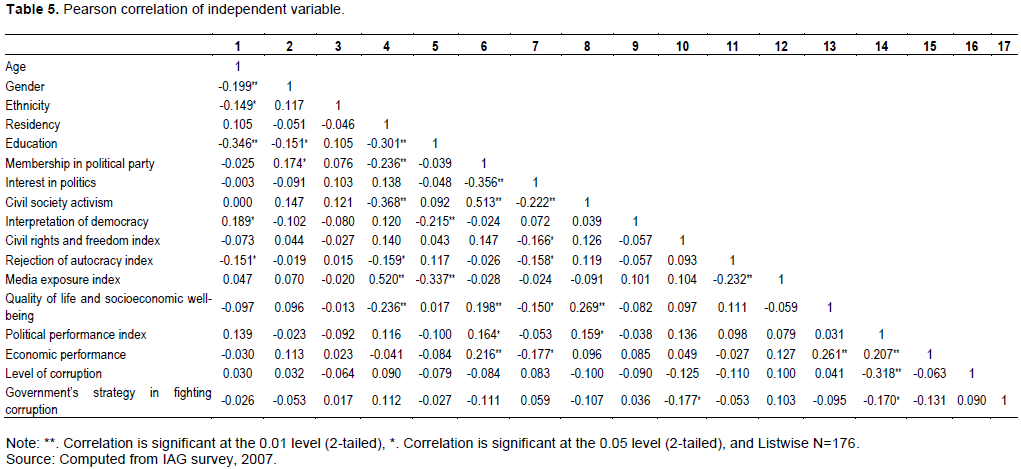

Multicollinearlity test among independent variables

Before running multiple regression analysis, a natural point of departure is to examine whether the independent variables of this paper meet the test of multicollinearlity assumption of linear regression analysis. Basically, as a statistical phenomenon, ‘multicollinearlity occurs when the independent variables are so strongly related to each other that it becomes difficult to estimate the partial effect of each independent variable on the dependent variable’ (Pollock, 2009: 193). As the general rule of thumb, if the magnitude of the correlation coefficient between the independent variable is less than 0.8, then multiple regressions will work fine. If the correlation is 0.8 or higher, then multiple regressions will not return good estimate’ (ibid).

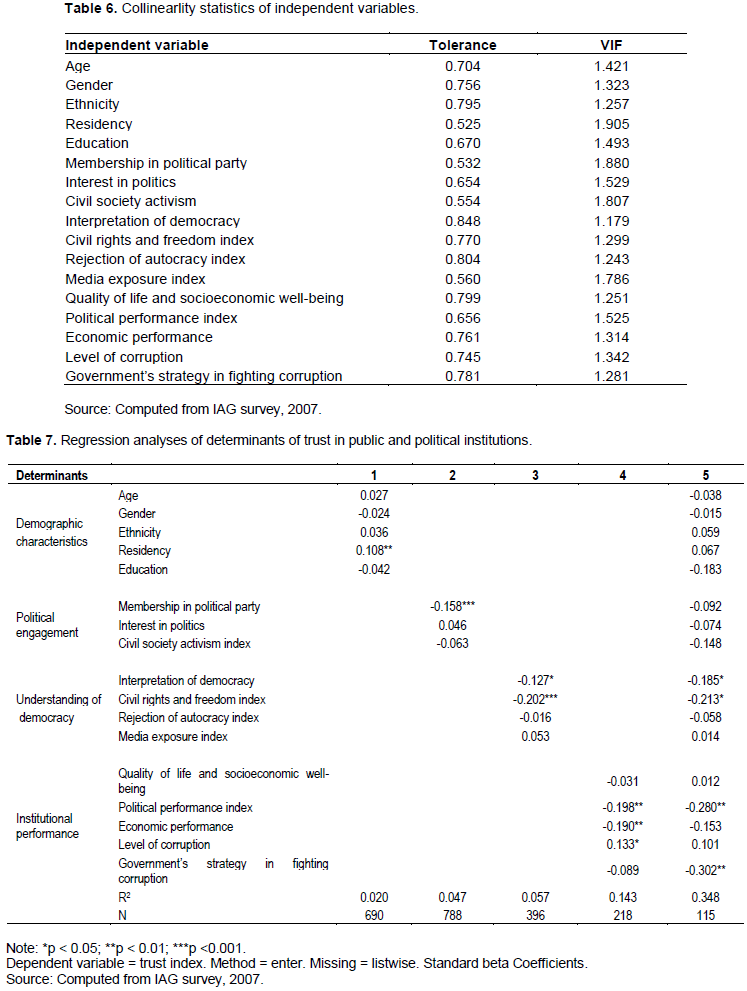

In order to check for the problem of multicollinearlity among independent variables of this paper, first a correlation matrix of all pairs of independent variables was run. However, simple bivariate Pearson correlation among explanatory variables is not sufficient for determining the extent of collinearlity in a given multiple regression analysis. Thus, additional tools: the variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance statistics were calculated for each predicator variable to detect multicollinearlity problems of this study. The critical level for the existence of multicollinearlity problem is when the tolerance and VIF statistics is less than 0.02 and greater than 10 respectively. As indicated in Tables 5 and 6, the magnitude of correlations among the independent variables does not appear to be a cause for concern about problems arising from multicollinearlity since the highest Pearson’s r was 0.520; the lowest tolerance statistic was 0.525, and the highest VIF value was 1.905. Given the favorable correlation results of the independent variables, OLS regression analysis was used to test the hypotheses that are posited upon the four groups of explanatory variables which are expected to influence trust in public and political institutions in Ethiopia.

Explaining variation in institutional trust in Ethiopia

We now turn to the question of the relative explanatory power of the different independent variables for variations in trust in institutions. What are the main factors driving the dynamics of citizens’ trust in public and political institutions in Ethiopia? Examining the factors that affect institutional trust provides a useful insight in identifying the central ingredients that engenders popular support to public institutions. The main focus of this sub section is to analyze the influence of institutional factors on the development of generalized trust. As indicated in the preceding section, there is no threat of multicollinearlity and the regressions equations employed were fitted to the data. To assess the relationship between the independent variables and institutional trust more rigorously, the OLS regression estimation strategy was used to test the hypotheses. In this analysis, it is known that the employed regression technique cannot prove direction of causality between the dependent and independent variables of this study. The OLS regression uses the following model with trust index as the dependent variable and demographic characteristics, political engagement, understanding of democracy, and institutional performance as the four independent variables. Assuming a linear additive relationship between the level of institutional trust denoted by y and a vector of explanatory variable denoted by x, linear regression model was used: Yi= βo + β1 X 1 + + β2 X 2 + …. + βi Xi + εi(Y is the generalized trust of citizen/ it is the reported level of trust for citizen, X is the explanatory variables associated with institutional trust in Ethiopia, βo the intercept of the population regression line and β1 is the slope of the population regression line, and ε is an individual level random error term). The linear regressions are for the following equation: Generalized Trust = X + β1 (age) + β2 (gender) + β3 (ethnicity) + β4 (residency) + β5 (educational level) + β6 (interest in politics) + β7 (membership in political party) + β8 (civil society activism) + β9 (interpretation of democracy) + β10 (civil rights and freedom index) + β11 (rejection of autocracy index) + β12 (media exposure index) + β13 (Quality of life and socio economic well-being)+ β14(political performance index) + β15 (economic performance) + β16(level of corruption) + β17(Government strategy in fighting corruption) +εi.

As indicated in the theoretical underpinnings section of this paper, it is hypothesized a model that institutional trust in Ethiopia is shaped by citizens’ socio-demographic characteristics, political engagement, understanding of democracy and institutional performance. Table 7 displays the results of ordinary least squares models assessing the multivariate relationship between these variable groups and dependent variable of trust in public and political institutions. In order to evaluate the extent to which these variables are able to explain variance in institutions trust in Ethiopia, regressions analyses are separately conducted for these four variables and finally a combined model is tested that contains all variables. Table 7 presents the result of the multivariate regression analysis used to test the hypotheses and reports the five relevant models of this study. To document the variation of the dependent variables at the individual levels, let us begin to examine how the socio-demographic characteristics shape citizens’ trust in public and political institutions.

Model 1 examines the effects of demographic variables on institutional trust in Ethiopia. These include age, gender, ethnicity, residency and education. All these variables together in one regression model were combined. Based on the cultural perspective on trust in public institutions, it is expected that demographic variables would be positively related to institutional trust in the context of Ethiopia. Surprisingly, of the five demographic characteristic variables included in this model, there were no statistically significant associations with the four variables and trust in public institutions. The regression result displayed in this Model 1 does not support the hypotheses (H1a to H1c and H1e) formulated in section two regarding their effect on trust in institutions. In line with hypothesis H1d, it is observed that the model provides evidence in favor of H1d, stating that rural dwellers displays a higher level of trust than citizens living in urban areas. Overall, these findings in Model 1 are not consistent with earlier findings on political trust reported in Allum et al. (2010), Catterberg and Moreno (2005), Dyrstad and Listhaug (2013), Hutchison and Johnson (2011), and Kuenzi (2008). The results shown in Model 1 reveal that it explains only 0.2% of the total variation in the institutional trust index, and its explanatory power is relatively very weak or non-existent at all.

Model 2 includes political engagement variables to test their effects in influencing trust in public and political institutions. Of these, membership in political parties appears to be significantly but negatively correlated with institutional trust index. The empirical result in this model provides evidence in support of H2a. However, the negative regression coefficient indicates a relationship as predicated in the hypothesis of H2a (β= -0.158, p < 0.001). Citizens with no membership in political parties are associated with low level of trust in political institutions. Turning to interest in politics and civil society activism, there was no empirical evidence to support the hypothesized relationship that supports H2b and H2c. Hence, both of these variables are not significant in explaining trust in institutions. Thus, these findings lead us to reject both hypotheses. In this model, as a bloc, the three variables account for 4.76% of the total amount of explained variance in generalized trust and out of the three variables, the membership in political party significant coefficients suggests that political engagement is more inclined to institutional trust index in Ethiopia.

Model 3 examines the hypotheses regarding the group of variables categorized under the understanding of democracy. As posited in H3a, the more an individual attaches a positive value to democracy, the stronger his or her trust in political institutions. However, rather than this conventional modernization argument, the finding of this particular model is indicated by a negative coefficient (β= -0.127, p < 0.05). This implies that the higher positive views of democracy are associated with lower generalized trust in Ethiopia.

Concerning hypothesis (H3a), which assumed that the more an individual attaches positive value to democracy, the stronger his/her trust in political institutions, our model did not bring evidence in support of this expectation. In a similar vein, civil right and freedom indexes also demonstrated a similar result which is negatively and strongly associated to generalized trust. Yet, contrary to the hypothesis (H3b), respondents with stronger perceptions of the increased violations of civil rights and freedom, they are less likely to support the country’s institutions. Compared to the interpretation of the democracy variable, the impact of civil right and freedom index is the most powerful of the two variables (β= -0.202, p < 0.001). However, rejection to autocracy and media exposure index are the weakest variables in this model. They do not have statistically significant association with the generalized institutional trust. It is concluded, therefore, that in Ethiopia political trust is not predicated by both rejection to autocracy and media exposure variables, and hence it is rejected both hypotheses. In contrast to previous models, the share of variance attributed to this model slightly increased by 2%. The explanatory power of this model shows that 5.7% of the total variance residing in the popular attitudes toward understanding of democracy in Ethiopia.

In Model 4, it is estimated the contribution of institutional performance variables. The result demonstrates that two of the predicators do not have significant impact on citizens’ level of trust in public and political institutions in Ethiopia. Thus H4a and H4e are rejected. Contrary to common assumptions, political performance index and economic performance appear to be negatively associated with institutional trust in Ethiopia-showing that satisfaction with the political performance of the government does not predict generalized trust in Ethiopia as hypothesized. Regarding the effect of political performance index indicator, the model consistently shows a negative effect of this variable on the institutional trust. The economic performance indicator is significantly and negatively related to the dependent variable. This implies that lesser citizens’ popular perception of the regime’s performance at handling the national economic condition, the lower their trust in the institutions. Consequently, the more Ethiopian citizens perceive political institutions as poorly performing, the less likely they are to trust those ineffective institutions. Concerning hypothesis (H4d), which assumed that the higher an individual perceives the level of corruption in state institutions to work, the lower his or her trust in the institutions, Model 4 brought partial evidence in support of this expectation. As opposed to what is hypothesized, the finding of this model indicates that respondents with lower perceptions of the level of corruption exhibit a higher level of political trust. The overall explanatory power of this model is 14.3% of the variation in institutional trust.

The fifth and the final set of regression analyses combine all the independent variables in one regression equation. In this combined model, four statistically significant findings emerge. First, variables measuring residency, membership of political party, economic performance, and level of corruption are no longer statistically significant. The significance of interpretation of democracy and political performance variables persists. Second, the variable measuring the government’s strategy in fighting corruption is statistically significant. Contrary to expectation, the result of this model indicates that citizens’ evaluation of the government fight against corruption has a negative association to institutional trust in Ethiopia. It seems that the various window-dressing anticorruption measures of the government have yet to create a positive impression in the eyes of the majority of citizens. Third, all things considered using the degree of explained variance as an indicator of the model’s relevance, this model is almost explains 35% of the variation. This implies that this model captured more than one third of the total variation of institutional trust. The overall impression given by the combined model is that institutional performance is an important source of confidence among citizens’ trust in public and political institutions in Ethiopia. Fourth, compared to all the explanatory variables of this model, as well as the preceding models, the government’s strategy in fighting corruption stands out as the most important single predicator of institutional trust (β= -0.302, p < 0.01).

The aim of this paper was twofold. Firstly, it explored the pattern of citizens’ institutional trust. Secondly, it set out to explore the source of citizens’ institutional trust from both cultural and institutional performance perspectives. The findings of this study reveal that citizens’ trust in public institutions varies extensively from one public or political institution to another. In a comparable perspective, this study also revealed that citizens’ mean score of common trust in political institution in Ethiopia is analogous to what has been observed in other countries of SSA. Particularly, the overall level of citizens’ generalized institutional trust is slightly above the regional average.

The findings of this paper suggest that institutional performance matters for explaining the source of citizens generalized trust. The level of skepticism in political institutions in Ethiopia is driven more by the gap between the perception of citizens’ expectations and the actual performance of public institutions. In light of these finding, what could the incumbent regime in Ethiopia do to increase popular trust in public and political institutions? It is concluded that citizens’ popular trust in Ethiopia is a function of their expectation of the quality of the services offered and their evaluations of the government’s efforts to provide services in a fair and equitable manner. The government thus should promote policies that are likely to increase the institutional capital of public and political institutions of the country.

What are the implications of this article finding? The implications of this finding may be significant for at least two distinct reasons. Literature on citizens’ trust in public and political trust in institutions in Ethiopia is very scarce. More research on the source of citizens’ trust in key governance institutions is necessary not only to uncover how institutional performance affects citizens’ perceptions and their actions in dealing with state institutions, but also to ferret out how performance shapes the nature of citizens’ engagement in public and political institutions at both micro and macro levels. In this regard, the primary contribution of this study is relevant with regard to addressing the dearth of information on citizens’ trust in public and political institutions in Ethiopia. As indicated in the first part of this paper, for institutional trust studies, there are two contending theories for explaining the source of citizens’ trust. This paper has explored institutional trust from both cultural and institutional performance perspectives. Theoretically, this study extends the literature on trust research. It contributes its own share since its findings emphasizes the importance of institutional performance theory in explaining citizens’ institutional trust in Ethiopia. The contribution of this paper is that it extends the existing knowledge on institutional trust and the explanatory factors by applying in the Ethiopian context, which had been neglected as an object of study in the realm of institutional trust research. It is found partial support for the key hypotheses that shed light on an interesting interplay between explanatory factors and institutional trust in the Ethiopian context. On the whole, the findings of this paper reveal how institutional performance matters for explaining the source of popular trust in Ethiopia. Lastly, it is claimed that the findings are not the only answers to the research questions, since there could be alternative views upon which political trust can be explained.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

The research presented in this paper was undertaken by financial support from the Norwegian State Educational Loan Fund (Lånekassen).

REFERENCES

|

Adem A (2012). Rule by law in Ethiopia: Rendering constitutional limits on government power. CGHR Working Paper.

|

|

|

|

Alemayehu H (2001). Overview of Public Administration in Ethiopia. Tangier: CAFRAD-African Training and Research Centre in Administration for Development.

|

|

|

|

|

Allum N, Patulny R, Read S, Sturgis P (2010). Re-evaluating the Links Between Social Trust, Institutional Trust and Civic Association. In J. Stillwell, P Norman, C Thomas, P Surridge (Eds.), Spatial and Social Disparities: Understanding Population Trends and Processes. London: Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg pp. 199-215.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Assefa F (2011). Separation of powers and its implications for the judiciary in Ethiopia. Journal of Eastern African Studies 5:702-715.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bahru Z (2000). The Problems of Institutionalization in Modern Ethiopia: A Historical Perspective. In A Mekonnen, A Dejene (Ed.). The problems of institutionalization in Modern Ethiopia: A Historical Perspective Ba Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Conference on the Ethiopian Economy, October 8-9, 1999, Addis Ababa Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Friedrich Ebert Stiftung pp.13-22.

|

|

|

|

|

Berhane GM (2002). The Ethiopian freedom of mass media has been disregarded and still remains in an uncertain future. Quartal 4:641-650.

|

|

|

|

|

Berhanu M, Vogel E (2006). Bureaucratic Neutrality among Competing Bureaucratic Values in an Ethnic Federalism: The Case of Ethiopia. Public Administration Review 66(2):205-216.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Berman B (2004). Ethnicity, Bureaucracy & democracy: The Politics of Trust. In B Berman, D Eyoh, W Kymlicka (Eds.), Ethnicity and Democracy in Africa. Oxford: James Currey pp. 39-53.

|

|

|

|

|

Bouckaert G, Van de Walle S, Kampen JK (2005). Potential for comparative public opinion research in public administration. International Review of Administrative Sciences 71(2):229-240.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bratton M (2010). Formal versus informal Institutions in Africa. In L Diamond, MF Plattner (Eds.). Democratization in Africa: Progress and Retreat. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press (Second ed.) pp. 103-117.

|

|

|

|

|

Bratton M (2013). Measuring government performance in public opinion surveys in Africa: Towards experiments? Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

|

|

|

|

|

Bratton M, Chu Y-h, Lagos M, Rose R (2005). The People's Voice: Trust in Political Institutions. In InternationalIDEA, Ten Years of Supporting Democracy Worldwide. International IDEA pp.61-71.

|

|

|

|

|

Breen M, Gillanders R (2013). Political trust, corruption and ratings of the IMF and the World Bank. Helsinki: Dublin City University.

|

|

|

|

|

BTI (2012). BTI 2012 -Ethiopia Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung.Burnell P (2004). Building Better Democracies: Why political parties matter. London: Westminster Foundation for Democracy.

|

|

|

|

|

Catterberg G, Moreno A (2005). The Individual Bases of Political Trust: Trends in New and Established Democracies. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 18(1):31-48.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chang EC (2013). A Comparative Analysis of How Corruption Erodes Institutional Trust. Taiwan Journal of Democracy 9(1):73-92.

|

|

|

|

|

Christine A, Sapir EV, Zapryanova G (2012). Trust in the institutions of the European Union: A cross-country examination. In: L Beaudonnet, DD Mauro (Eds.). Beyond Euro-skepticism: Understanding attitudes towards the EU (Special Mini-Issue 2 ed.). Retrieved October 22, 2012, from

View.

|

|

|

|

|

Dalton RJ, Weldon SA (2005). Public Images of Political Parties: A Necessary Evil? West European Politics 28(5):931-951.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dejene A, Yigremew A (2009). Indigenous Instituions and Good Governance in Ethiopia: Case Studies. In Good Governance and Civil Society Participation in Africa. Addis Ababa: OSSREA pp.141-162.

|

|

|

|

|

Delhey J, Newton K (2005). Predicting cross-national levels of social trust: Global pattern or Nordic exceptionalism? European Sociological Review 21(4):311-327.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dessalegn R (2008). Policy Research Instituions and Democratization: Recent Experience and Future Challenges. In A. Taye, & Z. Bahru (Eds.), Policy Research Instituions and Democratization: RecenCivil Society at the Crossroads: Challenges and prospects in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa: Forum of Social Studies pp.143-157.

|

|

|

|

|

Diamond L (2007). Building Trust in Government by Improving Governance. Paper Presented to the 7th Global Forum on Reinventing Government: "Building Trust in Government", Sponsored by the United Nations Session V: Elections, Parliament, and Citizen Trust, Vienna, June 27, 2007. Vienna.

|

|

|

|

|

Dyrstad K, Listhaug O (2013). Citizens' Confidence in European Parliaments: Institutions and Issues. In WC Müller, HM Narud (Eds.). Party Governance and Party Democracy. New York: Springer pp.159-174.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hovde RL (1994). Democracy and Governance in Ethiopia: A Survey of institutions, Issues and Initiatives in the Transitional Period. In HG Marcus, G Hudson (Ed.). Papers of the 12th International Conference of Ethiopia Studies, Michigan State University, 5-10 September 1994.

|

|

|

|

|

Lawrenceville, NJ: The Red Sea Press, Inc. pp.127-150.

|

|

|

|

|

Human Rights Watch (HRW) (2014). "They Know Everything We Do": Telecom and Internet Surveillance in Ethiopia. Amsterdam: Human Rights Watch.

|

|

|

|

|

Hutchison ML, Johnson K (2011). Capacity to trust? Institutional capacity, conflict, and political trust in Africa, 2000-2005. Journal of Peace Research 48(6):737-752.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

InterAfrica Group (IAG) (2007). Ethiopian Opinion Poll Survey Report. Addis Ababa: IAG. Iroghama IP (2012). Trust in Government: A Note from Nigeria. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences 2(6):326-336.

|

|

|

|

|

Kassahun B (2005). Parliament and Dominant Party System in Ethiopia . In M. M. Salih (Ed.), African Parliaments: Between Governance and Government. Palgrave Macmillan, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, New York pp. 162-182.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kassahun B (2009). Decentralization and Governance: The Ethiopian Experience. In Good Governance and Civil Socieity Participation in Africa. Addis Ababa: OSSREA pp. 113-140.

|

|

|

|

|

Kpundeh S, Khadiagala GM (2008). Information Access, Governance, and Service Delivery in Key Sectors: Themes and Lessons from Kenya and Ethiopia. World Bank.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kuenzi MT (2008). Social capital and Political Trust in West Africa: A Comparative series of national Public attitude surveys on Democracy, markets and civil society in Africa. Working Paper 96, Afro-Barometer. Retrieved April 22, 2013, from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Lavallée E, Razafindrakoto M, Roubaud F (2008). Corruption and Trust in Political Institutions in Sub-Saharan Africa. Working Paper No. 102, Afrobarometer.

|

|

|

|

|

Listhaug O, Ringdal K (2007). Trust in Political Institutions: The Nordic Countries Compared with Europe. Norwegian Political Science Meeting, NTNU, Trondheim, January 3-5.

|

|

|

|

|

Lyons P (2013). Impact of Salience on Differential Trust across, Political Institutions in the Czech Republic. Czech Sociological Review 49(3):347-374.

|

|

|

|

|

Mainwaring S, Scully TR (1995). Building Democratic Institutions: Party Systems in Latin America. (S Mainwaring, TR Scully, Eds.). Stanford: Stanford University Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Matlosa K (2006). Political Parties and Democratization in the Southern African Development Community Region: The Weakest Link? . Johannesburg: EISA.

|

|

|

|

|

Mierina I (2011). Political Participation and Development of Political Attitudes in Post-Communist countries, PhD thesis. Retrieved March 18, 2013, from View

|

|

|

|

|

Mishler W, Rose R (2001). What are the origins of Political Trust? Testing Instituional and Cultural Theories in Post-Communist Societies. Comparative Political Studies 34:30-62.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mulugeta A, Cloete F (2006). Public Policy-Making in Contemporary Ethiopia: An Antomy of Instituions, Roles and Leverage, 1991-2004. African Insight 36:141-159.

|

|

|

|

|

Newton K, Norris P (1999). Confidence in Public Institutions: Faith, Culture or Performance? Panel 14-2T What's Troubling the Trilateral Democracies? the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Atlanta, 1-5th September 1999. Retrieved April 04, 2013, from View.

|

|

|

|

|

Nishimuko M (2008). The Role of Faith-based Organizations in Building Democratic Process: Achieving Universal Primary Education in Sierra Leone. International Journal of Human and Social Sciences 3(3):172-179.

|

|

|

|

|

Norris P (1999). Institutional Explanations for Political Support. In P. Norris (Ed.). Critical Citizens: Global Support for Democratic Government. Oxford: Oxford University Press pp. 217-235.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Pino ED (2005). Attitudes, Performance, and Institutions: Spanish Citizens and Public Administration. Public Performance and

|

|

|

|

|

Management Review 28(4):512-531.

|

|

|

|

|

Pollock PH (2009). The Essentials of Political Analysis. (T. Edition, Ed.) Washington, D.C.: CQ PRESS.

|

|

|

|

|

Rolef SH (2006). Public trust in parliament-a comparative study. The Knesset Information Division. Jerusalem: The Knesset Information Division. Retrieved October 20, 2013, from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Schoon I, Cheng H (2011). Determinants of Political Trust: A Lifetime Learning Model. Developmental Psychology 47(3):619-631.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Shi T (2001). Cultural values and political trust: A comparison of the People's Republic of China and Taiwan. Comparative Politics 33(4):401-419.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Skjerdal TS (2010). Justifying Self-censorship: A Perspective from Ethiopia. Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 7(2):98-121.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Stokes SC (2006). Do Informal Rules Make Democracy Work? Accounting for Accountability in Argentina. In G Helmke, S Levitsky (Eds.). Informal Instituations and Democracy: Lessons from Latin America. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press pp.125-139.

|

|

|

|

|

Svedin LM (2012). Accountability in Crises and Public Trust in Governing Institutions. New York: Routledge.

|

|

|

|

|

United Nations Economic Commision for Africa (UNECA) (2005). African Governance Report 2005. Addis Ababa: Economic Commision for Africa.

|

|

|

|

|

Wong TK-Y, Wan P-S, Hsiao H-HM (2011). The bases of political trust in six Asian societies: Institutional and cultural explanations compared. International Political Science Review 32(3):263-281.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yang Q, Tang W (2010). Exploring the Sources of Institutional Trust in China: Culture, Mobilization, or Performance? Asian Politics and Policy 2(3):415-436.

Crossref

|

|