Since the arrival of new democratic train in West Africa, elections have been characterized with naked violence and irregularities which have negatively manifested in economic underdevelopment and political instability. To this end, understanding the dominant nature and character of the electoral management bodies of Nigeria and Ghana to identify a body that is substantially functioning well is central to this paper. This study found a more stronger INEC in terms of electoral management comparing the previous elections with 2015 general elections, yet issues such as non-permanent position of her experienced principal officers, nature of funding, ineffective working relation with other stakeholders are still challenges. This paper discovered that a substantial level of autonomy, permanency in membership of Ghanaian Electoral Commission (EC), proper funding and a doctrine of Inter Party Advisory Committee significantly contributed to its electoral success; by extension democratic consolidation. This study was of the view that Nigeria stands to distinguish itself, if it meticulously adopts and adapts Ghana’s viable electoral model.

It is incontrovertible that in early 1990s, the third wave of democracy blew in West Africa, while countries in this sub-region were forced to comply with this new trend of political order. Being a system of government with distinct values and traits, democracy celebrates free, fair, credible and integrity-based elections. In this context, the option of elections being modes of acceding political power was not negotiable. This implies that elections are a backbone of democracy. Elections in a free and fair sense constitute a fundamental criterion of a good democratic order. Indeed, without elections democracy is unthinkable because it is a platform through which people express their minds as regard who lead them. To Agbaje et al. (2011: 7) globally, credible elections have become a major factor whenever issues of democracy, democratization and good governance are raised. Meanwhile, the nature and character of elections (credible or not) determine largely its acceptability and by extension the end product of the produced government. Essentially however, sound electoral management body is required to achieve positive and desired end product of the election. In fact, Omotola (2014:24) asserts that good elections are said to be impossible without effective electoral governance. This suggests that effective and independent electoral commission is germane to credible elections. In addition, Electoral Management Bodies exhibit important effects on the quality of elections and democracy (Lundstedt and Edgell, 2020:8). To this end, electoral Management Bodies do not only effect democratic processes but shape the conduct of various actors in electoral game.

Regrettably however, robust electoral management bodies are missing in many countries of West Africa sub-region, Nigeria inclusive in spites her enormous resources and strategic position in the continent. Disappointedly, some elections held in these countries were characterized with naked irregularities, violence, killings, arsons, thus at times translate into socio-economic crisis, poor standard of living, poverty, underdevelopment and seismic political instability. In the context of Nigeria in particular, aside the 2015 general elections believed to be relatively peaceful, other elections have been characterized with condemnable irregularities. This was vividly captured from the assertion of the former INEC Chairman that:

The formidable challenge remaining to be addressed is how to continue to bring further improvements to the electoral process and prevent a reversal to the old order of chaotic, undemocratic and violent elections, with attendant negative consequences of authoritarian bad governance, instead of the desirable good and democratic governance (Jega, 2011:21).

In a similar vein, challenge of election administration was also noticed in Ghana. As succinctly argued by Oquaye (2012:5) in 2008, Ghana was at the boiling point of crisis owing to NDC serious complained that opposition party NPP and Electoral Commission of Ghana planned to manipulate election results. The foregoing assertions suggest that there is a fundamental problem of constructing democratic governance (via election) in Nigeria and Ghana even, if not the entire West Africa sub region. Hence, Hounkpe and Fall (2011) says that there are perceptions in West Africa sub-region on whether elections are of international best practices or poorly managed and badly conducted. Therefore, if elections perceived as workable general solution to dictatorial government, the need for an autonomous, sound and robust electoral management body became quite imperative. It is against this premise that our focus is on comparative study of the electoral management bodies of Ghana (EC) and Nigerian Electoral Management Body (INEC). Structurally, this study acknowledged and justified the centrality of elections to democratic system in its introduction; how elections have been a great threat to democratic stability in Africa and Nigeria in particular formed the statement problem. Secondary data collection approach was carefully adopted. Relevant concepts explored and discussed while the history; similarities as well as differences in the EMBs of both Nigeria and Ghana also formed important section of this study. Extant lessons to be learned from one electoral institution and other formed the concluding part.

Statement of the problem

Considering elections as one of devices through which diverse interests can be expressed equally and comprehensively, credible elections are among the chief ingredients of a good democratic system. In essence, democracy is unthinkable without free, fair and credible elections. However, viable electoral management body is very crucial to any electoral success. It is unfortunate that over the years, the performance of electoral management bodies in many West African countries has not been quite impressive because elections were characterized with irregularities, violence, killings, arson which has socio-economic crisis, political instability and underdevelopment effects. In Nigeria for instance, previous elections have been marred with series of irregularities. According to Urji and Nzodi (2012: 6) in Nigeria, elections are usual in recent time; meanwhile the integrity of these elections is subject of worry for the stakeholders in this industry. As asserted by Ugochukwu, (2009) and INEC (2007), the volume of litigations brought before the election petition tribunals and nullified election results by competent courts largely attested to dissatisfactions that greeted the 2007 general elections (quoted in ibid). Furthermore, in the history of post-election violence in Nigeria, the bloodiest violence happened in 2011 general elections. Indeed, it was uneventfully captured by Urji and Ndozi, that:

In fourteen Northern states where post-electoral violence was prevalent, violent protesters killed several people, including an unspecified number of National Youth Service Corps (NYSC), private houses and churches were burnt, thousands of people were displayed from their homes and places of business (2012:6).

In a similar vein, albeit prior to the conduct of 2015 elections, Abdulahi Smith has maintained that since her attainment of independence in 1960, all the general elections conducted in Nigeria were characterized with violence of different magnitude.

Moreover, the story was not completely different in 2015 general elections, because cases of violence were recorded particularly in the Southern and Eastern parts of the country. In fact, the leader of EU election observers, Fisa was reported to have asserts that during the 2015 general elections, violence was reported across the country. This violence includes: clashes among political parties, attack on the electoral officers and voting materials. Credible reports have shown that problems were very severe in Rivers and Akwa Ibom States (Agbaje, 2015; Newswatch Time). Additionally, another international observer Bekaren succinctly argued that what characterized the election was far from international best practices and the standard set by INEC (News Agency of Nigeria, 2015).

Meanwhile, cases of electoral irregularities were also noticed in Ghanaian electoral process. According to Jockers et al. (2009), the pocket of violence that characterized Ghana general elections may in comparison be less than what was noticeable in other countries within the region; yet to undermine these pockets of violence is to place the country on a surface of potential severe electoral violence (cited in Amankwaah, 2013:5). In fact, a former parliamentarian and Professor of Political Science rightly submitted that:

Some Ghanaians look for their passports and sought solace abroad, as many stored food against the expected war; Churches and Mosque were filled with panic stricken prayer warriors. As the final results were being awaited, NDC Youth armed to the teeth invaded the EC head office and burn vehicle tyres…. In 2012 the panic scenario was repeated (Oquaye, 2012:5).

Consequently, the aforementioned pocket of electoral challenges has manifested in voters apathy and at the long run which has reduced the level of citizen’s participation in electoral process, hence governance. Considering the efficacy of this menace on our fledgling representative democracies, there is compelling need for urgent solution to avert undesirable democratic reversal. It is against this background that this paper intends to attempt a comparative appraisal of electoral management bodies in Nigeria and Ghana with a view to improve electoral management system in the selected countries.

Aim of the study

The study aims at comparing the electoral bodies of both Ghana and Nigeria.

1. To understand the level of independent of the Nigeria electoral body (INEC) and Ghana electoral management body (EC).

2. To identify areas of similarities and dissimilarities between the two electoral management bodies.

3. To recommend ways in which the less effective one could be more efficient.

Electoral system

The dominant nature of an electoral system and its acceptance by the stakeholders in the electoral process determine largely how elections advanced democratic order. Electoral system means the rules by which elections are conducted (Almond et al., 2011:85). This according to them determines who can vote, how people vote and how votes are counted. William (2008) viewed electoral system as an established method of creating collective choice ultimately via voting. According to this book, what are central to a good electoral system are: the sum number of available seat; the widen nature of each districts; the seats allocation laws from votes cast and carefully designed ballot papers that guaranteed voters’ preferences.

Indeed, in contemporary world, the combination of the above variables and adherence to different laws and processes, varieties of electoral systems emerged. Obah-Akpowoghaha (quoted in Ebirim, 2013:12) opined that, an electoral system means difficult procedures adopted to select those who represent the masses in public offices particularly in a democracy. To Obah-Akpowoghaha, country’s political life does not only affect by the preferred electoral system, but also, benefits as well as the costs are shared accordingly among the candidates and political parties. In this view, Jibrin (2010) argues that most controversy about electoral systems centered on the rules for converting votes into seats. Such rules are not only important but they are democratically technical. The conversion of votes into seats formed the inner workings of democracy. Such a framework is essential to the political machine. Most time electoral systems make provision for the way and manner through which people’s representatives are to be elected or chosen. Hence, elections are perceived as activities that are complex because of diverse elements that are involved and benefits from one another.

In the perception of Nnoli (cited in Ebirim, 2013:12) an electoral system entails the extant laws and processes that serve as guidelines for voters in the course of performing their franchise and shape how the parliamentarians occupy the allocated seats in the legislature. According to Nnoli, all laws specifically made and nationally made body of rules defined largely, the procedures, rules and regulations that govern ballots. Also, public institutions entrusted with the responsibility of managing elections either addressed as government Department (as we have in Swaziland) or as an autonomous Electoral Commission (as in Lesotho). Also, some scholars have argued that primarily, what an electoral system does is that votes won by political parties are translated into seats. This is done at every level (general, regional or state or district levels) of elections. In another development, a non-governmental international body called International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (2009) maintained that, electoral systems defined, in addition structured the laws that guide the ballots. It also helps in determining the characters to elect, the nature of political campaign, the functions of political parties and ultimately, who rules.

Furthermore, a preferred electoral system could be a viable mechanism of social re-engineering. It suggests simply that, as a framework, electoral system could encourage consensus building in a diverse and polarized society. A good electoral system is chiefly appreciated as it converts the cast votes by the electorates into available political office seats and as such, determines the preferences voters have. It also influences individual voter, candidate as well as political party’s behaviours. Consequently, a country’s electoral system is a viable technique that is used to measure the number of elected positions in government. It helps to identify individual persons and political parties that are awarded seats after the elections. In other words, this explains that a good electoral system as a political institution is at the core of any representative democracy.

Election administration

It is irrefutable that election administration is a pivot task geared towards stemming a widely celebrated liberal democracy. Election administration which is also known as electoral governance has attracted different perception from scholars owing to its centrality to establishment and sustenance of democracy. According to Omotola (2010:539) election administration is demanding tasks which have elements of: making laws, implementation of these laws and element of adjudication. In electoral sense, law making means a designed procedures and regulations that guide the electoral game; rule application addresses the question of implementation of designed rules while the rule adjudication implies the resolution of disputes that greeted the elections. This in essence means that the interaction (positively) of various structures of government and processes is crucial to the outcome of election.

Moreover, Jinadu (1997: 2) viewed election administration as an arrangement engaged in by the electoral management body to have public offices occupied through elections. To Jinadu, when issue of election administration is raised, both the structure and the process are of concern. Structure is the established body entrusted with powers to arrange and monitor elections. In Nigeria, INEC is the structure that has the mandate of conducting elections. On the other hands, process according to Jinadu means the guidelines to follow; the rules that must be adhered to by various actors involved. Indeed, these rules encompassing: setting up electoral management body, selection and composition of its members, voters’ registration, candidate nomination, voting, ballots sorting and counting, results declaration, staff training, constituency delimitation, voters’ education and more importantly registration of political parties. In his submission Beckett (2011) added that, issue of funding, provision of needed logistics, contribution of government, and independent of the commission and tenure of members of electoral management body are all essential to electoral administration.

However, it is of concern noting that good election administration is still in question most especially in developing countries including Nigeria. Fairly organized, properly coordinated and satisfactorily conducted elections have been a contentious issue in Nigeria. The nature of electoral system adopted by different countries affects the good standing of electoral administration. Meanwhile, country’s internal make-up as well as electoral context is a factor that influenced the type of electoral system adopted by different societies. In Nigeria for instance, the simple majority and plurality system adopted has impacts on the success or otherwise of the system. Owing to first-past the post and simple majority arrangement, the attitudes of the candidates, voters and political parties are shaped largely by the electoral system adopted. This, by implications, makes electoral governance a serious challenge. Political parties and their candidates have seen elections as do or die matter because of instilled fear of zero-sum game system. Hence, deepening electoral administration in Nigeria has been a herculean one.

Electoral management and integrity

Contemporarily, there are concerns about sound electoral management in many democracies. Put differently, many elections worldwide faced series of condemnations following noticeable malpractices. According to Norris (2014) (in James, 2014) established democracies are often thought to be immune from more serious ‘first order’ difficulties yet problems associated with election administration and management are common to them. These include mistakes administratively committed while conducting elections and strategies adopted that resulted in poor and undesirable outcomes. It is imperative to note that studies which seek to understand how elections can be improved upon have traditionally focused on the electoral laws, electoral systems design, electoral laws and design of electoral administration. According to James (2014), electoral management is defined as inter and intra-organizational interaction that used policy frameworks and available assets that are keys to good elections delivery.

Findings show that poor electoral management discouraged citizens’ trust in electoral process most especially in developed democracies; it affects consolidation and fosters violence elections in developing democracies (Elklit and Reynolds, 2002; Pastor, 1999). The professionalization of electoral management bodies observed by James (2014) was perceived to be a critical plan and goal-setting of international Organizations. According to Global Commission on Elections (2012), there are new studies on policy instrument used within electoral management boards to manage the people, resource and technology at their disposal. Ultimately, however, there have been some works on what constitutes ‘good’ EMB’ performance. Elections are often evaluated in terms of whether international norms, (op cit.) democratic norms (Birch, 2011) or natural laws are broken. According to James (2014), a range of frameworks have been developed to more narrowly assess EMBs and election administration. Many of these frameworks go beyond looking at the flaws in elections that directly result from office-seeking statecraft (Ugues, in James, 2014).

Location of the electoral management bodies within the structures of the state

In recent years, different criteria have been used to classify electoral management bodies. Fundamental among these was their recruitment exercise. In a context that allows civil servants to organize elections, the EMBs follow governmental approach. It is a judicial approach in a situation where judges are appointed to conduct elections. Electoral management bodies are regarded as multi-party in orientation where members of electoral management body are from different political parties. Also, approach of electoral management body is believed to be expert based when a selected renowned, experienced and independent minded individual made up of body that organizes and conducts elections (Garber, 1994; Harris, 1997 cited in Lopez-Pinto, Bureau for Development Policy UNDP, 2000). In another development, EMBs have also been viewed on the basis of structural characteristics. Klein (1995) argued that, this is to look at the EMBs from angle of recruitment (permanent, Independent, not centralized electoral system) (Klein, 1995). In addition, the variations in country’s political, cultural as well as their democratic evolutions shaped the institutional character of their EMBs. Globally, development of electoral system has been conditioned with different factors. These include: An old established orientation of body of rule, readiness of actors to embrace dialogue during transition, nature of economy and level of dissatisfaction by the masses (Diamond et al., 1988; Bratton and Van de Walle, 1997). It is historical that, elections were conducted by the executive branch of government alone. However, contemporary democracies have moved towards highly independent and multi-party oriented electoral management bodies. In addition, the legal stance of many electoral bodies in modern democracies is not negotiable. For instance, it is evidence that constitution of some countries provided for electoral management bodies of equal status with the three arms of government. In fact in Venezuela and Costa Rica, electoral management bodies are the fourth branches of government. Additionally, many countries in the continents of Asia and Africa have their electoral management bodies constitutionally empowered (Lopez-Pinto, 2000).

Nigerian Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC)

Under the Nigerian 1999 Constitution, there was a provision for the establishment of an independent electoral management body known as INEC. Indeed, Section 14 (1) states that; there shall be a body known as the Independent National Electoral Commission INEC. The commission shall have a Chairman as the head who shall be Chief Electoral Commissioner. In addition, Twelve (12) other members known as National Electoral Commissioners shall work along with the chairman to deliver on the mandate of the commission. These set of people as provided for in the constitution must be people of impeccable character. The chair must not be less than fifty years of age while other twelve members must not be less than forty-years of age (Constitution, Federal Republic of Nigeria 1999). Furthermore, the power of INEC as stated by Section 14 (5) of the Constitution includes the power to: organize elections for the offices of President and Vice-president, organize as well as conduct elections into executive and legislative public offices across the country, register political parties, provide guide-lines for campaigns and monitor the operations of political parties, compile the voters’ registration to achieve credible and acceptable elections in Nigeria. Other assigned duties to the INEC by the Parliament must as well be performed by the commission. The scope of INEC responsibility was clearly provided for in the 2010 Electoral Act as amended. These include: The guideline to be followed by political parties to get duly registered, provision of voters’ cards for qualified citizens, the activities of the commission on Election Day, the nature of election malpractice and procedures for electoral dispute resolutions.

Nigeria’s electoral management body: A historical synopsis

It is of assertion that a body with the primary responsibility of administering elections in Nigeria has over the years featured differently yet structurally indifferent. To substantiate this thought, Adetula (2007:7) succinctly noted that Nigeria has experienced several dissolutions, re-constitution and restructuring of electoral management bodies as a result of military incursion in politics. It is historic that prior to the 1960 independence (1958-1959), of existence was the Electoral Commission of Nigeria (ECN). It was headed by R. E Wraith who conducted the 1959 general elections. Upon her attainment of independence in 1960, the constitution of Nigeria provided for a Federal Electoral Commission (FEC). This commission organized and conducted post-independence general elections of 1964 and 1965 respectively. Following the military incursion of 1966, FEC was dissolved, and new Federal Electoral Commission (FEDECO) was constituted by the former President Olusegun Obasanjo in 1978 with Chief Micheal Ani as the head. This commission successfully organized the 1979 elections in tune with the transition to civil rule agenda of Olusegun Obasanjo and ushered in Second Republic under the leadership of Alhaji Sheu Shagari. Also, in 1983 Justice Ovie-Whiskey assumed the headship of the commission (FEDECO) and as such organized and conducted the general elections. Furthermore, in 1987, after a successful Coup staged by Ibrahim Babangida, a new electoral body was established by Decree No 23, which was headed by Professor Eme Awa; Prof Humphrey Nwosu and Prof. Okon Uya respectively. In 1994, National Electoral Commission of Nigeria NECON was established by late General Sani Abacha led military government. This commission was headed by Chief Sumner Dagogo-Jack from 1994 to 1998. Subsequently, the sudden demise of Abacha in June 1998 saw the emergence of new electoral body known as the Independent National Electoral Commission INEC. This was established by General Abdusalam Abubakar’s administration following the dissolution of Abacha’s NECON electoral body.

Apparently, INEC chaired by Honourable Justice Ephram Akpata conducted the transitional general elections that gave birth to Fourth Republic in 1999. In the year 2000, Abel Guobadia was appointed and he conducted the 2003 general elections; while, Maurice Iwu organized the 2007 general elections following his appointment as a chairman of the commission in 2005. However, there is no gain saying that the appointment of a highly discipline academic Prof. Attahiru Jega as a new chairman of INEC in 2010 forced the commission to repositioned itself and delivered on assigned mandate. This was obvious in the 2015 general elections. The ruling Peoples’ Democratic Party PDP lost to the main opposition party All Progressive Congress APC. This is a mile stone in Nigeria’s electoral history. On June 30th 2015, Jega’s tenure expired and Amina Sakari acted until the appointment of Mamood Yakub by President Muhamadu Buhari as the new head on the 29th October, 2015. Upon completion of his tenure of five years, Professor Mamood Yakub was on 27th October, 2020 re-nominated by the president for another five years’ term which requires Senate confirmation. It must be added that INEC has representation in all the 36 states of Nigeria including Federal Capital Territory, Abuja.

Ghanaian Electoral Commission (EC)

The issues of electoral democracy and management of elections in Ghana before 1960 were quite challenging. Indeed, there was an issue of EC independence and the confidence of citizens in the electoral process and the body that manages elections. The return of Ghana to democracy in 1990s provided for a new electoral management body which has the trust and confidence of the citizens. Like in the case of Nigeria, the activities of Electoral Commission of Ghana go beyond organizing elections; it includes: the registration and monitoring of the activities of political parties. Also, the EC of Ghana has a level of independent. It has power to organize itself and determine its own internal affairs. As an institution entrusted with the management of elections, Electoral Commission of Ghana is not immune from some challenges. In fact, staff welfare, voters’ registration management, and ineffective coordination of relevant institutions are among the factors that have not strengthened the Electoral Management Body of Ghana.

Ghana’s electoral commission: An evolution

Since her independence in 1957 and prior to the new wave of democratization in 1993, Ghana had used ‘autonomy electoral management body’. Historically, between 1968 and 1974, only one commissioner was in charge of elections in Ghana. Between 1982 and 19992 the National Commission for Democracy NCD was in charge of elections as the body conducted District Assembly elections. In a similar vein, in 1992, the interim National Electoral Commission (INEC) was established. This body conducted the 1992 general elections and also managed the Constitutional Referendum that took place in the same year. Moreover, on a legal sense, the present Electoral Commission came into existence in line with the provision of the 1992 Constitution. Specifically, Article 43, 44, 45 and 46 of the constitution provided for the creation of EC of Ghana (Electoral Commission, 2008). In fact, of specification was the Ghana Constitution on the composition of the electoral commission members, their qualifications, salaries and term in office. The core functions of the commission as well as its independence of any person and /or institution were left not unspecified by the constitution. Meanwhile, despite the strong constitutional provision to ensure EC autonomy, the commission still faced criticism from the opposition parties. By implication, the EC has faced a lot of challenges in the elections conducted in 1996; 2000; 2004; 2008 and even in 2012 since Ghana’s democratic restoration in 1992.

Nigeria-Ghana electoral bodies: The similarities

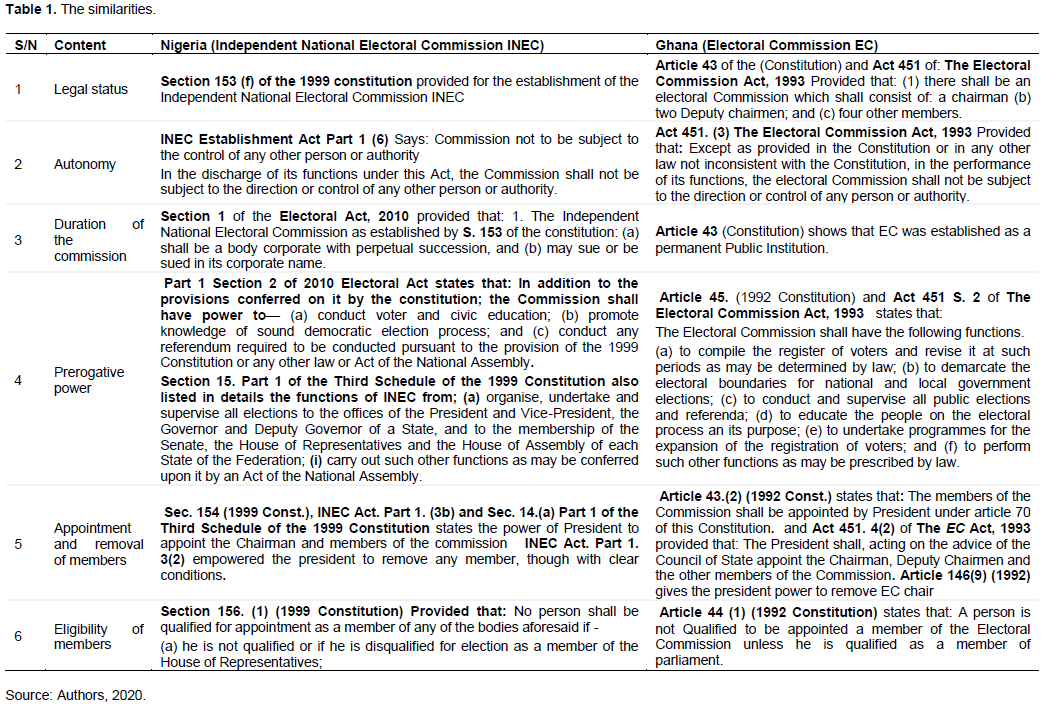

Considering their geographical location on the Africa continent; suffered European domination; years of political independence; military incursion and democratic experience Nigeria and Ghana are better positioned to learn from each other, ultimately institutionally. It is axiomatic that the two countries have established Electoral Management bodies in which their structure, organization and composition have manifested in their outputs and level of citizens’ confidence. Table 1 shows mostly the areas of uniqueness of Nigerian Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) and the Electoral Commission (EC) of Ghana more importantly in respect of legal frameworks.

It is vivid that the two electoral management bodies (INEC & EC) were dully established by the extant body of rules. These are: The 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria and the 1992 Constitution of Ghana. In the context of Nigeria, from its name “Independent National Electoral Commission” signifies “autonomous body” free from any interference whatsoever. It is a permanent institution that conducts elections into various offices in the country. Also, in Ghana, Electoral Commission of Ghana is responsible for the management of its electoral system. Both legal documents provided that: the Electoral Commissions are not subject to the direction or control of any person or authority. Hence, these two bodies are similar in this direction. Additionally, owing to the strategic position of both INEC and EC in their respective body polity, their autonomy was clearly provided for and guaranteed by the constitutions. This also makes Ghana and Nigeria electoral institutions unique. In the same vein, the two electoral bodies are permanently established as public institutions saddled with the responsibility of managing elections. This simply suggests that they are not intermittent electoral bodies, like we have in some countries.

In another development, both electoral bodies possessed very important prerogative and strong referees. As clearly provided for in their various constitutions, both INEC Nigeria and EC of Ghana have unique prerogative powers and functions. Under this, they have power to: Control and supervise all public elections and referenda; Register and control of the activities of political organizations; Define the sites of polling state; Printing ballot paper; it recruits and train staff that man the polling stations and those that manage the entire electoral process. Both EMBs do accredit domestic and foreign election observers; provision of important information for the successful completion of the electoral process. Both INEC and EC receive and distribute accordingly, the materials allocated to the political parties; invalidate the results of elections before or after publication; thy investigate irregularities when brought to its notice. Furthermore, the power to remove EMB’s chair lies in the Mr President of both countries.

Evidently, on Thursday 28th June 2018, President Nana Akufo-Addo removed the Chairperson Mrs Charlotte Osei and her two deputies, Mr. Amadu Sulley and Ms. Geogiana Opoku Amankwah from office. The President’s action followed the recommendation of the committee set up by the Chief Justice, Sophia Akuffo, in response to various allegations of fraud and corruption leveled against them. Similarly in Nigeria, on 28th April, 2010, the former President Goodluck Jonathan wrote and directed former Chairman of the Independent National Electoral Commission INEC Professor Maurice Iwu to embark on leave as a preparation for his exit expected to constitutionally end on 12th June, 2010. As such, the most senior electoral commissioner was to take-over from Iwu before the appointment of a substantive INEC boss. The forgoing evidences from the two countries clearly attest to the unique power of Mr. President in Nigeria and Ghana to appoint and remove the chair/chairperson of their EMBs. Another important area of convergence in these electoral bodies was the prerequisite of membership. Both Nigerian and Ghana legal frameworks required members of the commissions to be of the same status with the members of the parliament in respect of their qualifications. That is, to be eligible for EMB membership you must be qualified to be a parliamentarian.

Nigeria-Ghana electoral management bodies: The divergence

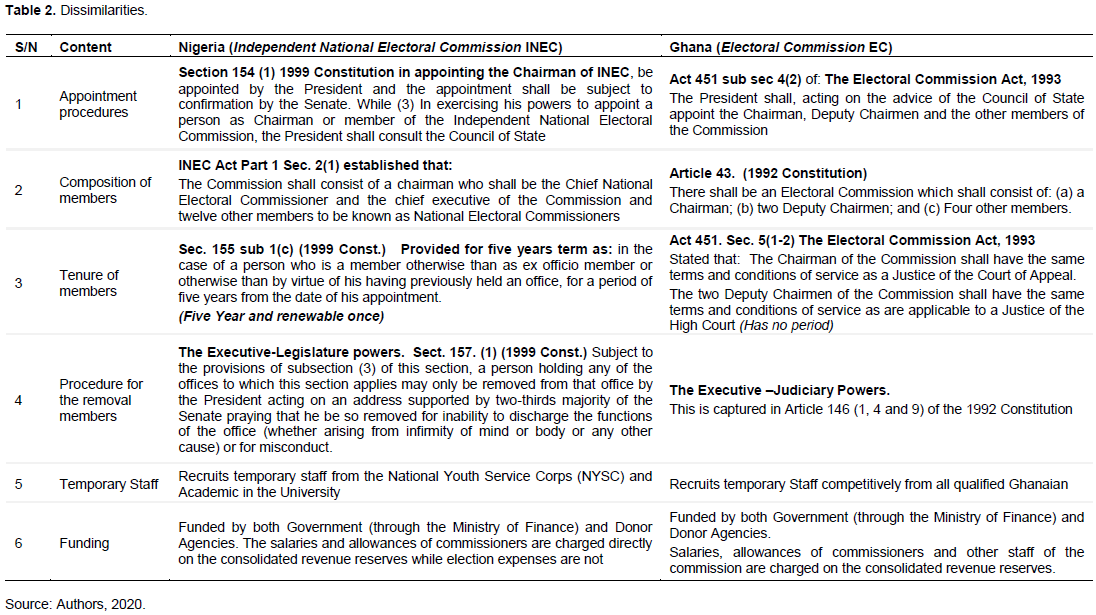

As unique as the EMBs are, they clearly have variables that differentiate them from each other. Indeed, the observed variability in their outputs might not be unconnected to their legal, administrative, structural and contextual differences. As shown in Table 1 INEC Nigeria and EC of Ghana are not unique in some areas.

Appointment process

As shown in Table 2, the appointment of the members of INEC in Nigeria is by proposal by the President. This is in consultation with the Council of State. Meanwhile, such a nominee requires the confirmation of the Senate. This implies that, the power of Mr President to appoint INEC Chair/ Chairperson is checked by the Council of State as well as the parliament. Put simply, the appointment of member of the electoral body in Nigeria is a joint effort of the executive and the legislature. Evidently, on 27th October, 2020 President Muhammadu Buhari re- nominated and forwarded to the National Assembly the name of immediate past INEC chair Professor Mahamud Yakubu for another five-year term. The president has no unilateral power of appoint INEC boss. Hence, Senate confirmation is strategic to the appointment of INEC chair in Nigeria. Meanwhile in Ghana, the proposal for the appointment is also from the president in consultation with the Council of State though for mere advice. The Council of State is just an advisory body established by the 1992 constitution without any major power. Another trait in Ghana case is the need for a strict compliance with the tax regulations of Ghana. The president does not need to consult the parliament in the appointment process. Indeed, the position of of the Council of state is not binding on the president.

Composition of members

In terms of composition of members, the two electoral bodies differ. In Nigeria, as provided for in the INEC Act Part 1 Sec. 2(1) established that: there would be chairman also known as chief National Electoral Commissioner as the head of the commission. Other appointed members are known as National Electoral Commissioners. Indeed, the appointment of these members also requires the confirmation of the Parliament as in the case of the Chair/ Chairperson. Two National Commissioners are appointed from each geo-political zone while one Resident Electoral Commissioner is appointed from each state of the Federation. He/ she is deployed to INEC offices outside their states of origin. In the case of Ghana, the composition of the EC comprises six (6) members who work directly with the chair to deliver on their core mandate. It consists of two Deputy Chairmen and four other members. Before they could be appointed, the laws require that presidential nominee must fit to be member of the parliament. Hence, in Nigeria, the Electoral Commission composes of thirteen (13) members. The Commission has representatives in all the thirty-six (36) states of the Federation and the Federal Capital Territory. The Commission has representations in all the states of the federation and Federal Capital. In Ghana, the Electoral Commission consists of seven (7) members. Among these seven, three work permanently for the Commission while others are not permanently engaged by EC. At the local level, three members represent the Commission.

Tenure of office

Quite significant as area of difference between the two bodies is the tenure of office. In Nigeria Sec. 155 sub 1(c) (1999 Constitution) provided for five years term. In Nigeria, the tenure of members’ electoral body (INEC) is five years. This is renewable but once. But the electoral commission has permanent members who continue to work after elections. What is fundamental here is that, there is clear tenure of office for the members of the Commission. Their work and engagement with the commission is within the constitutionally stipulated five years terms. In other words, their appointment has tenure. It is instructive to note that former INEC chair Attairu Jega has to leave office after his five years terms despite a widely acknowledged success recorded. In the case of Ghana, members of the Electoral Commission have no fixed tenure of office. According to the 1992 Constitution, the Chair/ Chairperson of EC enjoys and has similar conditions of service as a Judge of Court of Appeal. This Implies that if infraction(s) was not committed, the EC Chair/ Chairperson is irremovable. He/she serves in the office till the retirement age of seventy 70 years as applicable to the Appeal Court Judge. Similarly, the Vice-Chair of the Commission also enjoys the same benefits like a high court judge. They are irremovable too; having committed not infraction(s) that constitutionally warrant their removal. Hence, they hold and maintain their positions until the fixed retirement age of sixty-five years. Moreover, with a sense of uniqueness, the appointment of EC chair/person and other two Deputy chair has no specific duration until their retirement as public officers. Electoral commissioners in Ghana are largely independent from influence and control of political class unlike what is observable in some neighbouring countries. This suggests that, the span of service and responsibility of Ghanaian electoral chair and other two deputies is wider than those whose members have a fixed tenure (Five Year and renewable once). Unlike, in Nigeria where the Chairman of INEC spends renewable 5 years, in Ghana, it is worthy of saying that they optimally utilize the acquired experiences of their principal officers as he/she stays for long in office. This is very fundamental.

Removal of the chair/chairperson and members from office

Another area of divergence in the Nigeria and Ghana electoral institutions was the process and procedures for removing the chair/chairperson and appointed members of the electoral bodies. In the context of Nigeria, the Constitution demands the joint efforts of both the executive as well as the legislature before this could be done. In fact, as the appointment of electoral Chair/ Chairperson is a Constitutional issue, so their removal from office is a constitutional matter. The decision to dismiss INEC boss originates from the president. This must be supported by the 2/3 members of the Senate. The procedure is difficult because it requires the endorsement of 2/3 majority of members of the upper legislative arm of government. (Hounkpe and Fall, 2011:24). This procedural rigidity is to have the members of the Commission well protected and unduly distracted in the course of doing their constitutional duties. Meanwhile, in Ghana, it is more or less executive/Judiciary relations before the removal of the Electoral Commission member(s). The basis and procedure for the removal of EC Chair/Chairperson from office is unique. There is no undue rapport between the executive and the commission. Hence, undue influence from the executive or the legislature hardly characterized the system. To have the chair of the commission or any of his deputies dismissed, proven incompetence, mental or physical incapacity and misconduct must be established. As presented by Fall et al. (2011:91) the process of removing EC Chair or any of his/her deputy goes thus:

1. Upon receiving a petition for the removal of Electoral Commission chair or any of his/her deputies, the president requests the determination of the ground and substance of the petition by the Chief Justice of Ghana.

2. When founded a prima facie case, the chief justice sets up a five-member investigative committee. The Judicial Council appoints three of them from member of the High courts and/ or regional tribunal chairs. The remaining two members are selected by the chief justice in line with the Council of State’s advice. The committee members could be selected from the legal profession, Council of State or from the parliament.

3. It is expected of the committee to investigate the issue(s) raised against the EC chair/or his/her deputies, and makes objective recommendations to the Chief Justice of Ghana. Upon receipt, the Chief Justice communicates the executive, while the action of the president must be within the recommendations of the committee.

In essence, the president being the chief executive with a significant influence on the appointment process also has the final say when the issue of dismissal of EC chair and/ or the deputies arises.

Recruitment of temporary staff

In another development, the Electoral Commission of Ghana and INEC of Nigeria differ in respect of election-day staff recruitment. Following the 2010 electoral reform initiative under Attairu Jega, the commission recruits its temporary (Ad-hoc) staff from the National Youth Service Corps NYSC as well as academic from the University. This is to foster needed credibility and integrity of elections. The involvement of impartial election officers NYSC members and senior university officers) in electoral process has reposed the lost faith and belief in the outcome of the elections and the political system (Aliyu, 2017:97). It would be recalled that prior to this reform, INEC employed civil servants as Ad-hoc staff during the elections. Many believe that these civil servants are not immune from the influence of their employer (government) hence questions the credibility of elections conducted. In the case of Ghana, EC recruits its temporary workers among general public based on merits. Hence, the stakeholders repose trust in the commission’s process of election-day staff recruitment. These temporary staff are recruited and used at the polling stations during elections.

Funding exercise

In Nigeria, from the standing point of the legal framework, the commission enjoys funding from the government, aids [and] grants (Donor assistance such as UNDP, DFID, EU CIDA) to carry out its functions. Section 81 sub section (1) of the 199 Constitution and the 2010 Electoral Act as amended requires the submission to the Federal Ministry of Finance the yearly estimate of the Commission’s expenditure and income (Fall et al., 2011:132). For the members of the commission, salaries are paid though as prescribed by the National Assembly. As such, the amount was determined by the Revenue Mobilization and Fiscal Commission (RMFC). Meanwhile, Section (3-5) of the 2006 Electoral Act made a clear provision for the establishment of the Independent National Electoral Commission Fund. Fund from the Federal government, interest from Investments and grants from donor agencies are paid (deposited) to this established Electoral Commission Fund. Hence, disbursements are made accordingly. Consequently, government indirectly influences and controls the activities of the commission. This logic set in, as the commission, must defend its budget; have it vetted by the Finance Ministry as provided for in the Electoral Act. In fact, the revenue estimate and expenditure of financial year is prepared and presented to the parliament for necessary approval (Fall et al., 2011). Indeed, the forgoing understanding gives room for the interference of the National Assembly in the activities of the commission. INEC must be added and has to join a queue at the Ministry of Finance for the needed fund (Omeiza, 2012:182). Meanwhile, in Ghana, Article 10 of the Electoral Commission Act provided that the commission’s administrative expenses which include salaries and wages of its workers are charged on the Consolidated Fund (Fall et al., 2011:92-93). As in the case of Nigeria, the Electoral Commission of Ghana received funds from both Federal Government as well as support from the development partners. The Electoral Commission of Ghana largely decides its budgets. Of course, the budget is submitted to the executive, and for any amendment(s) on it, there must be consultation with the commission. This has really helped the commission to be far less subjected to undue influence via financial process. In another development, five years prior to the implementation of its plans, the Election Department of the commission prepares and approves the budget of the commission. Hence, this early preparation of budget helps the commission to solicit donation from the development partners on time.

Electoral management bodies and other election stakeholders in Ghana

In comparison with Nigeria, the Electoral Commission of Ghana established a cordial relationship with the major actors in the electoral process. The commission gave premium and provided a fertile ground for effective collaboration between it and other important actors. In fact, within its logic, good collaborative measure with political parties has provided an avenue for actors to have a more conducive electoral process. For instance, Intra-party Advisory Committee IPAC fosters mutual understanding and respect for the commission. This also imbues trust and confidence of the stakeholders in the electoral process. As a framework, EC through the instrumentality of IPAC takes into consideration the concerns of both parties as well as candidates in elections. Also, IPAC is a mechanism of information sharing about: the arrangement made and the challenges confronting the commission. It drives towards itch-free electoral exercise. Indeed, there have been calls for the formalization of IPAC so as to make it more desirably effective and efficient.

The above discussed relations also extended to the security agencies. Indeed, there is The National Election Security Task Force (NESTF) which was an initiative of the commission. The EC of Ghana brought forward various security forces that are germane to the peaceful and violence-free elections. For good planning and proper training of the security operatives, NESTF as an innovation has helped the Commission to adequately budget for security and provides a peaceful atmosphere for elections to take place.