ABSTRACT

Conflicts and insurgencies constitute some of the greatest challenge to societal peace and development. While daily effort are made by government and humanitarian organisations to address the problem of conflicts and insurgency, the absence of quality health service for those affected by conflicts have further amplified the potential for conflicts and human insecurity. The paper examines conflict and insurgency as barrier to quality health service for internally displaced persons in the North Eastern part of Nigeria. It argues on the failure and inability of the Nigerian government to respond to the exigency of conflicts and insurgency, tugging on instability which affects quality health services. Access to global quality health services has become unattainable and inaccessible and the implication for the worsening health conditions of internally displaced persons in Nigeria. As the outcome of a qualitative research carried out to interrogate the impact of conflict and insurgency on global quality health services on internal displacement persons, its methodology relies heavily on in-depth and key informant interviews. The paper concludes that unless concerted effort through legal and political will are put in place to address the problem of conflict and insurgency in the northern part of the country, especially with the growing activities of Boko Haram and farmer-herders conflicts, quality health service will become unattainable, especially for internally displaced person who are not only victims of insurgency, but also vulnerable to poor quality service in the process of their integration and durable solution.

Key words: Conflict, insurgency, counter-insurgency, global health services, internally displaced person, and Northern Nigeria.

Conflicts are considered a major barrier to social, political and quality health services in Africa; between 2000 to 2017, the number of internally displaced persons rose by over 10 million (Martin, 2018). At least about two-thirds of the countries in Africa have experienced conflict leading to the displacement of millions of people (Burke et al., 2009). As stated in the report of the Geneva based internally displacement Monitoring Centre, approximately 33.3 million displaced persons are found in Africa. In Nigeria, the insurgent’s activities of Boko Haram militants and the perennial Niger Delta conflicts in the last one decade have displaced millions of people from their homes. This is not isolated from the protracted inter-communal clashes resulting from a combinations of ethno-religious and boundary disputes in the North central and North Eastern part of Nigeria respectively (Oshaghae and Suberu, 2005). Notwithstanding, the increasing strains between Fulani herdsmen and farmers have also resulted in over 700,000 displacements from the middle belt of Nigeria (NRC, 2016). The Nigerian government appears to be having a very difficult time confronting persistent security issues, thereby leading to an increasing number of internally displaced persons in the country. The intensity of these conflicts has further tugs on the gloomy picture of violent conflicts in Nigeria and their implication for the growing concern of health status of refugee and internal displacement in Nigeria.

While the health of internally displaced persons have become an issue of serious concern for the government, conflicts and insurgency have undermined a well-coordinated global health service, resulting in increasing rate of infectious diseases, depression mental disorder and epidemic disease. In the context of the breakdown and collapse of medical structures and facilities, vulnerable people especially the internally displaced population often suffers from severe inhuman and degradable conditions with risk factors often aggravating communicable diseases, due to the plummeting consequence of overcrowding, lack of drugs and emergency, absence of medical professionals among others challenges. Although, the Nigerian government in 2017-2018 improve the health sector, the continuing Boko Haram and herders-farmer’s conflicts in the North continue to exacerbate the breakdown of health facilities infrastructure. The shortage of health professional and manpower, especially Doctor, Nurses and Community health workers have deepens the crisis in the management of health sector, explaining why these health professional were reluctant to work, even in accessible areas because of the fear of ongoing conflicts. Conflicts and insurgency, therefore, leading to displacement and influx of returnees and displacement often disrupt global quality health service and programmes implementations.

This lack of data and information has been responsible for why many IDPs lived in both official and unofficial camps, often with illness, physical and psychological trauma and minimal access to health care and basic essentials such as food, clothing, shelter, clean water and good sanitary conditions (IDMC and Norwegian Refugee Council, 2015). Perhaps more alarming than the numbers of IDPs are the poor conditions under which most of the IDPs are living. The majority of Nigeria’s over 1.5 million displaced persons are housed in overcrowded camps across the disturbed northern regions. These camps which are mainly school facilities and empty government government buildings with few basic amenities are supervised by the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA, 2016). These facilities are usually temporary rather than permanent ones. That said, the lack of coordination and poor environmental conditions has also resulted in poor health standards and their implication for the quality of health services for IDPs.

Despite the increasing numbers of studies and institutional reports on IDPs and the various specific health challenges such as sexually transmitted disease, sexually and gender-based violence, post-traumatic stress disorder and depression among others (Ager et al., 2015, Owoaje et al., 2016), there is a dearth of studies on the effect of global quality health service on internally displaced persons in the North Eastern part of Nigeria. Apart from the fact that many of the previous studies focus on mental health, they also failed to provide a general picture of the health problems of the IDPs and their lack of access to global quality health service due largely to the consequence of insurgency. There is a growing acknowledgement that health service cannot be accomplished only by medical infrastructure, medical supplies and health care providers, there must also be a deliberate focus on quality health services which is the foundation of the World Bank report on “achieving quality health service in the year 2030” (World Bank, 2018).

Against this background, the paper examines conflicts and insurgency as barriers to global quality health service for internally displaced persons in North Eastern part of Nigeria. The paper is divided into four parts. Following from the background which is the first part, a conceptual understanding of conflicts and insurgence and internally displaced persons is advanced in the second parts. In the third parts, a critical interrogation and analysis of conflicts and IDPs in Nigeria is undertaken. The fourth part which is the discussion of findings highlights the internally displaced persons and global quality health service, stressing the lack of access and absence of a quality health service for IDPs and refugees and the consequences for renewed conflicts in Nigeria. It then follows with a conclusion and recommendation as appropriate.

The method used in this study is the qualitative method. This is principally so because the nature of the research questions developed for this study. Under this method, in-depth semi structured interviews, informant sources and documentary analysis were used to source information from respondents based on the series of open-ended questions rather than the use of standardized questions in quantitative surveys (Babbie, 2008:336). The open- ended questions allow for qualitative analysis of the views of respondents. Under this condition, the study serve to explore opinion and perceptions to ensure effective participation of the research subject and flexibility to probe the underlying assumptions and varieties of perspectives from them. This will help to ascertain the real health situation of IDPs at their various camps in differential to what is reported by the government. What follows are a discussion of the sampling strategy and size, conduct of in-depth interviews and ethical issues and problems encountered; analysis and data limitation.

Area of study

The study took place in the North Eastern part of Nigeria. The selected areas of the study are Yobe, Borno and Adamawa states. Notwithstanding, the study also explores other areas of the country where useful data and information vital to the study were sourced.

Sample and sampling size

The sampling method used for the in-depth interviews was quota sampling. The significance of this method is that there is no need for call-backs. The incidence of time-wasting is also reduced. The variables used in allocating the quota include geographical areas, gender, age and occupation/non-occupation. Participants were sourced from the broad spectrum of groups where the study took place. The objective was to capture a range of different perspectives on the effect of conflicts and insurgency on global quality health services to the internally displaced persons in Nigeria. Participants were thus selected from; Medical Doctors, Nurses and Midwifes, Community Health workers, Male and Female IDPs, Emergency management agencies, Traditional chiefs and Members of the community among others.

Data analysis

After the field work, thematic structures were developed to facilitate the sorting and grouping of evidence in a manner which provides clear structure for the interpretation and analysis of the data. Data were therefore analysed within the context of the thematic framework such as inadequate funding, service provision, health infrastructure, movement restrictions generated which also reflected the main sections of the interview schedule and informants’ sources drawn to generate cross-cutting themes and patterns from the respondent’s answers to the questions. The results of these were presented in narrative form and in tables where appropriate.

Ethical consideration

The study took consideration of some ethical issues which borders on concealment and secrecy. As noted by Babbie (2008: 66-77) qualitative research is more dire of ethical issues considering it ‘fulfil the principles of voluntary participation, inoffensiveness to participants, anonymity, and confidentiality and avoidance of deception’. Consequently, the research participants were assured of confidentiality of information disclosed in the course of the interviews and discussions. Such information shall be treated in strict confidence and would not be revealed to third parties. In addition, we guaranteed the anonymity of the respondents, ensuring that their names or identities were not revealed due to the sensitivities of the subject matter. Also, no one is forced to participate in the interviews and discussions; those who refused interviews were left out.

Limitations and constraints

Considering the sensitivity and nature of this research, the study suffers from some constraints which affected its general operational decisions about the exact strategy and methods for the field work. The time-frame for engaging in extensive field work, validation through meta-analysis and data information became extremely difficult. However, these quarantined issues were fully engaged given that the field work provided a basis for the confirmation of the evidence gathered. In addition, the field work was also pursued in line with standards and best possible practice that answers the research questions and objectives.

CONFLICTS AND INSURGENCY: CONCEPTUAL UNDERSTANDING

The growing number of violence-conflicts has widened the literature on studies on internally displaced persons in Africa. Despite many of these studies coming to the conclusion that conflicts are increasingly constituting a challenge to peace and security, less effort has been put in place to examine the bigger picture, especially the consequence of the dwindling quality of global health service for internally displaced persons in relation to a durable solution to conflicts.

In Africa, at least about two-third of countries in Africa have experience in conflict leading to displacement of millions of people (Burke et al., 2009). In his conceptual approach Bakut (2007: 2) had conceived conflict as the “pursuit of incompatible goals or interests by different groups or individuals”. To him, all humans and their social organisations have specific goals defined by their interest which is always in opposition to those of other groups. As a struggle over interest, power and scarce resources, groups tend to neutralise, injure or eliminate one another (Schmidt, 2000). This is the more reason why Addison (2003: 102) claimed that conflicts are a manifest clash of interests in which an individual or group of individuals tends to outdo or manoeuvre themselves in theactualisation of objectives. As a form or manifestation of conflicts, insurgency according to the United State Department of Defence (2007) has been conceived “as an organised movement that has the aim of overthrowing a constituted government through subversive means and armed conflicts” (Hellesen, 2008: 14). This definitional conception offered above suggests that insurgents are not only very deadly because of their attempt to undermine the sovereignty of a state and sharing their resources, they also employ unlawful means which transcend socio-political and religious strategies for advancing their course (Siegel, 2007). As a warfare, insurgency is characterised by protracted, asymmetric violence, use of complex terrains (mountains, forest jungle), psychological warfare and political mobilisation to alter the balance of power in favour of insurgents. These tactics being used by insurgents has been responsible for the failure of the federal government of Nigeria to tame the dreaded Boko Haram and Niger Delta insurgents.

In the broadest sense, insurgencies are characterised into two major forms: the national insurgencies and liberation insurgencies. Firstly, in the case of the national insurgencies, the principal antagonists are the insurgents and a national government. The difference between the government and the insurgents is defined in terms of legitimacy, ideological economic class and identity shaped by ethnicity, race and religion or some other political logic (Dowd and Drury, 2017). Secondly, the liberation insurgencies on the other hand pit themselves against the ruling group that is dubbed as alien to the rule by virtue of their identity, even if they are not. The preoccupation of the liberation insurgents in to free the country from what they perceive as imperialistic control. Some notable examples include anti-apartheid insurgency, Palestinian insurgency in the Middle East, Al-Qaeda/Taleban insurgency in Afghanistan among others.

The consequence of conflicts and insurgency has been the bane of many displacements and refugee flows across different parts of the globe, with Africa housing the largest number. Following this submission, the Geneva based internally displacement Monitoring Centre reported that approximately 33.3 million displaced persons are found in Africa, and with consequence for further conflicts Nigeria has been seen to have the highest number of displaced persons in Africa. For example, the 2014 Global Overview Report claims that Nigeria parades the highest number of persons displaced by conflicts. The phenomenon of growing conflicts is instigated by Boko Haram attacks and perennial communal clashes in the North Central and North Eastern part of Nigeria respectively. This has further been reinforced by the government counter-insurgent attack against several other warring groups with man and natural hazard induced disasters. At the same time, conflicts have also been induced by cultural inter-clan conflicts, social communal tensions, political induced violence, inter religious violence and government eviction (IDMC, 2012).

INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS: CONCEPTUAL EXPLANATION

According to International law, ‘IDPs are persons or group of persons who have been forced or obligated to flee or to have cause to leave their homes or place of habitual residence, in particular, due to or in order to avoid the effect of armed conflicts, situation of generalised violence, violations of human rights or, other natural or human-made disasters’ and who have not crossed an internationally recognised state border’ (UNOCHA, 2007: 1). This definitional conception offers above underpins two central components of IDP- the coercive or involuntary movement which occurs within national borders, some of which are instigated by armed conflicts, violence, human right violation and disaster (NRC, 2009). Clearly, this factor had deprived people of the most essential protection mechanism, especially access to quality health services and sustainable livelihood. The second component of the IDPs is the movement within national borders. Considering that IDPs remain under the control of national authorities, the expectation is that they are expected to have improved conditions much like the un-displaced people (Olukolajo et al., 2014), yet the absence of a coordinated health care service has contributed to the growing rate of traumatic stress of IDP resulting in lack of access to medical and health care facilities.

There is yet to be an estimate of the total number of IPDs. Few studies have only provided a speculative figure which sometimes is subject of controversy. Although, depending on the factor responsible for displacement, civil strife or natural disaster often propel a high number of displacements. Several times, securing the exact figure of displaced persons has been difficult, government sometimes reluctantly acknowledge the real numbers of IDPs and IDPs themselves might hide from identification, largely for reason of persecution (WHO, 2008). However, the figure of global IDPs had been estimated at over 20 million (IFRC, World Disasters Report, 2000). 10 million of these IDPs were found in Sub-Saharan Africa. This was followed by South America which has about 1.9 million with Colombia parading the highest number (IFRC, 2000). Other countries with a high incidence of internally displaced persons include Iraq, Afghanistan and the Russian Federation estimated to be around 1 million respectively (See, Save the Children War Brought Us here, 2000). The IDP’s population has also been tenured in countries like the Middle East, the Philippines and South Africa and Nigeria (See, Save the Children War Brought Us here, 2000). Specifically, according to Moremi Soyinka-Onijala, the former Special Assistance to the President on Migration and Humanitarian Affairs, estimated the number of IDPs in Nigeria to be round 500,000 to a million (Brookings, 2006: 8). This position was buttressed by the federal commissioner for refugees who claimed that between 1999-2005 when communal clashes increased, around a

million people were displaced (ThIS Day, 17 April 2008). The figure certainly has increased with the spate of insurgencies in both the Niger Delta region and the North Eastern part of Nigeria. In addition to armed conflicts, perennial natural disaster such as famine, floods and climate change often conflate with displacement to make durable solutions and return patterns difficult (IRIN, 30 August 2007).

While it can be said that IDPs enjoy no special status nor do they possess any legal protection and assistance, a recent study only found US legislation providing minimal but not sufficient statutory support for government action on behalf of IDPs (See, Save the Children War Brought Us here, 2000). Notwithstanding, IDPs are covered by both domestic and international humanitarian laws and fundamental human rights instruments. When displacement occurred in the context of armed conflicts and violence, IDPs requires special attention including food shelter, clothing and health protection. Article 3 and Additional Protocol II of the Geneva Convention clearly stated that the protection for displaced persons, include care for the wounded and sick, with women and children at the core of these safety concerns (UNOCHA, 2007). The framework of actions for IDPs no doubt stresses the specific rights’ and protections’ needs and the duties of the government in ensuring safeguard of these vulnerable people which include the elderly, children and minors, pregnant women, and the disabled, chronically ill and more importantly those that are yet to find coping strategies. In many instances, internally displaced persons are among the most susceptible and vulnerable people, especially women and children. There have been reported cases of rape, sexual harassment, gender-based violence and uncontrolled birth leading to high infant and maternal mortality rate in several IDP camps in Nigeria (NRC, 2016). The impact of conflict has subjected IDPs to several consequences, not least food and security, but also effective health care which are significant to their recovery and returns. In the absence of these special needs, IDP suffers traumatic stress which not only impact on their general well-being but also on their health status (Ladan, 2007).

Beyond the psychological breakdown which IDP suffers, internally displaced people are vulnerable to human right abuse, especially the lack or denial of health care which are significant to their wellbeing and survival both in the IDP and post-IDP camp (UNHCR, 2011). This has continued to impair on the assessment of quality global health service which is central to how the human race can benefit from the global health service. The absence of a coordinated health and medical programme for IDPs has been criticised by several studies as an attempt to undermine the benefit of IDP from the transnational international refugee law (Kohn et al., 2007, Ladan, 2007). Poor health condition has been argued to be particularly prevalent among IDPs due largely to the absence of health care measures to meet up with the basic health and social needs of the IDP (Porter and Aslam, 2005). This factor has exacerbated the risk of mental disorder as revealed in Kenya, Nigeria and Western Papuan (Koehn, 2006).

In that instance, the recent study of mental disorders among the West Papuan IDP exposes a high degree of political persecution and deprivation and identifies a range of trauma experiences which has led to mental disorder. This mental health disorder has been linked to ‘separation anxiety disorder, persistent complex bereavement disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, generalised anxiety disorder and more’ (Tay et al., 2015: 178) which are consequence of conflicts and violence. While there is evidence that IDP benefits from international human rights and legal protection instruments (Ibanez and Moya, 2007), less attention has been focused on the quality of global health service, which are central to IDPs recovery. Studies have shown that women and children in IPD are vulnerable to physical and mental health problems and they also have special protection health needs (Mooney, 2005: 3). They can be victims of sexual violence even from camp administrators (World Bank, 2018). The consequence of sexual violence has a long-term effect which may lead to sexually transmitted disease, HIV, mental health and unwanted pregnancy (Mujeeb, 2015).

In concrete term, conflicts and insurgency, in the context of a growing internal displacement is anthetetical to global quality health services which promote human values and security. Peaceful environment is a pre-requisite for offering the required health services by healthcare professionals as well as atmosphere to offered quality services. Generally, the benefits of PPEs are effective health services delivery which is realized through health worker performance and good patient outcomes (Joanna Briggs Institute, 2005). The absence of peaceful and conducive environment therefore largely undermine the institutionalisation of quality health services, especially for IDP and refugees who are already requiring special attention. Such condition creates insecure and unsafe healthcare systems that negate effective and quality service delivery and durable solution to the problem of internal displament.

CONFLICTS, INSURGENCY AND INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT IN NIGERIA

Nigeria is a major theatre of major political contestation violently driven along ethnic religion and regional expressions. Some of these contestations have been woven around the control of state power, resources allocation and identity crisis. A number of these issues have destabilised the hitherto Nigerian stable political environment and have contrived the convergence and harmony which are potentially against centrifugal tendency (Oshagae and Suberu, 2005). Hence, civil strife, civil war, minority tension, ethnic and communal clashes have become common features of Nigeria. As posited by Oshagae and Suberu (2005: 4), given the “complicated network of politically silent identities, coupled with a history of protracted and seemingly stubborn wars and instability, Nigeria is high on the list as one of the most unstable states in Africa”. The submission above is not only a reflection of the recurrent crisis of regional and state illegitimacy which has characterised the country since independence, it is also a replication of the increasing violent conflicts which have engulfed the post 1999 democratic dispensation of Nigeria. The emergence of the Niger Delta militant and Boko Haram insurgents are notable examples of the rising wave of conflicts since 1999. Indeed, the outbreak of conflicts and insurgency in Nigeria has been strongly linked to the post democratisation trauma in which the militarisation of Nigerian society due to the prolonged legacy of military rule has been the basis why many groups express themselves in violence confrontation against the state.

CAUSES OF CONFLICT AND INSURGENCY IN NIGERIA

For the benefit of this study, two main theoretical frameworks will be used to explain the causes of conflict and insurgency in Nigeria. The first is the social economic perspectives and the second is the ethno-religion perspective. This is not to undermine other theoretical constructs such as relational vengeance, political feud, conspiracy theory among others that have been used to explain conflicts; the point however is that social economic and ethno-religion perspectives help to understand the basis of insurgency in Nigeria. According to the socio-economic perspective regarding conflicts, social-economic conditions of people are the defining pristine of conflicts. Every human being strives to be at a very good socio-economic condition and standard of living. The failure of this is the result of some of the conflicts in Nigeria. This theory is also rooted in the frustration/aggression thesis, which posited that the absence of favourable socio-economic conditions leads to aggression, the consequence of frustration (Dougherty and Pfaltzgrate Jr, 1990: 266). In other words, the deprivation thesis of ‘Ted Gur’ suggests that “the perceived disparity between expectation and need satisfaction often breeds frustration and aggression” (Midlarsky, 1975: 23).

The frustration and aggression thesis is seemingly corroborated in Nigeria where acute poverty is on the increase, and unemployment, ignorance and hopelessness have promoted criminal gangs and insurgents hoping to beat the system to address their social condition. If the current human development Index where Nigeria is ranked 152 out of 157 in terms of human development status in 2018 is anything to come about, then Nigeria is vulnerable to conflicts. This is not a coincidence given the United Nation Development Programme (UNDP) report of 2018 which noted Nigeria as the number one of the poverty countries in the world. Nigeria has 86.9 million of its estimated 180 million population living in abject poverty. That amounted to about 53.7 percent of its national population (UNDP, 2018). Nigeria took over from India as the country with the most depressing poverty situation. Such a trend is also indicated in its rising unemployment profile from 16.2% in 2016 to 18.80% in 2017 (National Bureau of Statistics, 2017). Some of these indices are symptoms of a state failure, in which a state failed to ensure public goods for its citizens. No wonder Nigeria’s failure to provide public goods and the associated structural crisis have culminated in several epithets by scholars which include ‘criminal state’ (Bayart et al., 1999), Prebendal state (Richard, 1987), disorder and political instrument (Chabal and Daloz, 1999). Suffering and smiling stateamong other sobriquet used by scholars (Bayart et al., 1999).

The consequence with a failed state has always been the rise of intense confrontation and criminal activities as witnessed by the activities of Boko Haram and Niger Delta insurgents. As noted by Herskovits (2012), it was clear in 2009 when the insurgency began that the root cause of violence and anger in both the North and South of Nigeria is endemic poverty hopelessness and excruciating social condition. Some of the socio-economic problems in Nigeria mirrored the incidence of frustration and aggression resulting in conflicts in Nigeria especially in the South-south and Northern part of Nigeria. Endemic poverty and hopelessness have led some youths to taking up arms against the state, becoming disenchanted and generally agitated. Studies and institutional reports have demonstrated that the rising spate of insurgency is the bye-product of poverty, inequality and relative deprivation of socio-economic conditions (Alozioenwu, 2012).

The ethno-religion perspective views ethnic and religion identities, and other factors related to it as a marker of conflicts. As observed by some scholars, religion plays a prominent role in the life of people and expresses itself as a key force of unity and conflicts in Nigeria. The inability of ethnic and religious leaders to reconcile religion diversities has been the basis of conflicts in many societies. This crisis is even more pronounced in pluralistic and secular societies like Nigeria. Nigeria has been engulfed in numerous ethno-religion strife and crisis. Many of these crises, according to Lewis (2002:2), “manifests in political mobilization, sectarian social movement and increasing violence”. Ethno-religious conflicts are difficult to differentiate because of the cross-cutting cleavages which they which connects them along ethnic lines (Canci and Odukoya, 2016). In that scenario, the Maitatsine, religious crises (1980), kafanshan-kaduna religion strife (2000), sharia crises (2000) behead the infidel-Allahu Akbar (1994), Ishagamu-Hausa reprisal attack are good examples of ethno-religious conflict which transcend religion to cut across ethnic factors. Most of these conflicts tie along ethnic fault line because of the cultural borderline which integrate religion into cultural ways of life of people (Oshagae and Suberu, 2005).

Most of these conflicts, in relation to the relative deprivation, expresses themselves through insurgency in Nigeria. While the Niger Delta and the Boko Haram insurgents have become the leading actors among violent groups contesting against the Nigerian state, there are other dangerous violent formations operating as a defender of community or ethnic rights. Such groups include Oodua People’s Congress, AREWA People’s Congress, Egbesu Boys, Ijaw Youth Congress (IYC), Movement for the Emancipation of Niger Delta (MEND) and Movement for the Realization of the Biafra state (MASSOB) among other dreaded groups in the country.

INSURGENCY AND INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT IN NORTH EASTERN NIGERIA

The North Eastern part of Nigeria has become the hotbed of serious conflicts and insurgency. It comprises Borno, Yobe, Taraba, Gombe, Bauchi and Adamawa states. Given the spate of Boko Haram insurgency in this region, the sovereignty of the Nigerian state has been under serious threat. Indeed, for example, it is the case that the insurgent Boko Haram control 20 out of the 27 local governments in Bornu state where their activities have been on the rise. By implication, a pocket of 7 local governments which include Maiduguri Metropolitan, Jere, Konduga. Kaga, Bayo Kwayakusar and Biu local governments are under the control of the government (The Nation, 2016). Since the Boko Haram conflicts in the region, about 17, 000 people are estimated to have been killed in the series of intermittent attacks on the host communities and government facilities (Amnesty International, 2010).

Apart from the Boko Haram insurgents, there are also pockets of communal clashes in parts of Taraba Plateau which have uprooted millions of people from their natural homes to leave in IDP camps. At the same time, the government led counter-insurgency operations against the people and other natural induced disasters have also forced people to migrate from their homes to take up temporary accommodation in IDP camps. The large number of IDPs was confirmed with the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC), a branch of the Norwegian Refugee Council, in April 2015 that about 1538982 people living in IDPs across Nigeria are the product of insurgency of communal clashes and natural hazards (IDMC, 2015). This is in addition to the other 47,276 IDPs in the plateau, Nassarawa, Abuja, Kano and Kaduna (NEMA, 2015). In terms of acute poverty, North Eastern Nigeria has the highest level of poverty in the country. Explaining the incidence of insurgency and conflicts in the region, such conflicts have been the bye product of the increasing displacement in Nigeria. This scenario was poignantly captured thus.

Recently, the North-East is reported to be the home of state with highest unemployment rate in the federation, that is, Yobe State at 60.6%, as at the end of 2011. It is the zone with highest number of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) totalling 11, 360 in the 1st quarter of 2012and in 2010-2011 with highest number of forced displaced persons of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) (about 22% or 82%, North-West with 31% or 116, 207 and North- Central with highest of 42% or 162, 281 out of 377,701) due to Identity-Based Conflicts such as ethno-religious and political conflicts and violent clashes between the religious militia/armed group (Boko Haram) and government forces. Hence, within this period of coverage, the North account for 95% of IDPs in paradox of Boko Haram, an armed group that promotes sectarian violence of a different dimension that has engulfed the entire zone in the history of Nigeria, that is neither inter or intra-religious but essentially against the western educated Muslim elite and government (Muhammad, 2012: 4).

Following the increasing number of internally displaced people in the country, the National Emergency Management Agency (NEMA) in 2016, reported that there are several IDP camps in Nigeria. Many of these camps were created to cater for displaced people. It was reported that many of these camps were located in the volatile North Eastern part of Nigeria where the activities of the dreaded Boko Haram insurgency have been on the increase. It should be stated that 16 of these camps were concentrated in Maiduguri, the capital of Bornu state and the number of IDPs in these camps ranges from 120,000 to 130, 000 persons (NEMA, 2016). They are also satellite camps spread across some local governments in the region. While the Regional Country Director of NEMA noted that the satellite camps housed about 400,000, it also stated that not less than another 1.2 million IDPs are putting up with their relatives (NEMA, 2016). From an official report, a total number of 1,934,765 displaced persons are currently domiciled in formal camps, host communities and satellite camps as a consequence of insurgency in the North Eastern states of Borno, Yobe, Taraba, Gombe, Bauchi and Adamawa states.

The above is the IDPs camp and their characteristics in the North Eastern part of Nigeria (Table 1).

The above indicates the situation and characteristics of DP camps in the North eastern part of Nigeria. It does not only reveal an increasing number of IDPs due largely to the consequence of Boko Haram insurgency, it further shows that the host communities accommodate more IDPs that even the formal and satellite camps across the area. In the context where the host community accommodates more IDPs, without adequate health, shelter, food and improve conditions, the likelihood is that IDPs suffer more from dehumanizing conditions without prerequisite quality health standard which is likely to breed mental disorder, psychological breakdown, and depression among many intractable negative human conditions. The above also depicts the lack of official IDP camps, as many IDPs often put up with the host communities and families, or even sought shelter in some major towns where it is complex to determine displaced people and those migrating for economic reasons. Such a pattern of migration is common in Lagos, Abuja and Port Harcourt (UNOWA, October 2007: 31). In this condition, many IDPs suffer from insistent institutional policies of forced eviction. In Abuja for instance, IDPs occupying informal settlement were forcibly evicted in large numbers as part of the implementation of the Abuja Master Plan (IRIN 23, November 2007). Under this situation, IDPs suffer serious neglect and face a number of challenges such as unfavorable government policies, sexual abuse, lack of shelter and food and above all, absence of quality health service which has undermined their reintegration and durable solution. Thus, it can be said that conflicts pose a debilitating challenge to IDPs, with serious consequence for aggravating and worsening the health problems of IDPs. Although government is making effort to prevent worsening health of IDP through numerous intervention, key informants indicate that neglect in the face of conflicts has led to psycratic mental disorder of many IDPs. There is a serious concern that quality health service is not available in IDP camps. Displaced women and girls have been the worse hit as access to basic rights and health services, including gender based violence in camps often undermined durable solutions (Human Right Watch, 2016).

Interview with the Zonal camp Coordinator of the North-Eastern zone in 2017.

INSURGENCY, IDP AND BARRIERS TO GLOBAL HEALTH QUALITY SERVICES IN NIGERIA

As stated above, it is no longer news that Nigeria is currently experiencing insurgency that has undermined the global health quality service. It is the case that the intensity of armed attacks and abuse against the civilian population and destruction of vital health infrastructure has increased over the years. Since the emergence of Boko Haram insurgents in 2009, key health services and architecture for displaced persons have been adversely affected. At the same time, the access of IDP to quality health service has been of great concern. Frequent blockades, fears of maiming and killing, and threats to public service providers by insurgents have been found to affect safe delivery of quality health services to war ravage IDPs. Due largely to lack of movement, unavailability of service providers, lack of drugs and monitoring of IDP camps by central health officials, global health quality service has been adversely affected in Nigeria (Borno State Health Sector Bulletin, 2016). In the context of poor-quality health services, progress at improving global quality health service is impaired (World Bank, 2018). On the basis of this, our findings are predicated on the following thematic issues which include impact of conflicts on migration of health workers, inadequate funding, service provisioning, health infrastructures, and movement restrictions.

IMPACT OF CONFLICT ON MIGRATION OF HEALTH WORKERS

As a consequence of fratricidal conflicts, findings show that health workers often migrate for fear or threat of maiming and killings. It is not uncommon to find both local and humanitarian health workers permanently abandoning their work place. Even though the local ones leave and sometimes return when the situation is calm, evidence suggests that many of them don’t return to their duty post. The most common cadre among these caregivers, according to the Yobe state Human Resources Information system (HRIS), are the doctors and nurses. This statement was further buttressed by an informant participant of the research when he noted as follows:

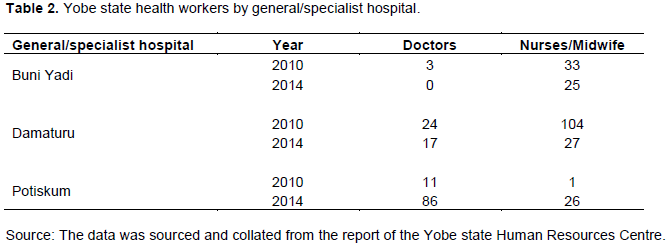

In relation to other health and community workers, doctors and midwives who are better at giving quality health service provision due to their professionalism are afraid to travel to some IDPs camps in conflict affected areas because of reprisal attack which is partly based on insurgent’s suspicion about health workers. In the course of our duty, many of us are harassed, intimidated and interrogated by insurgents as well as security personnel to establish our motives Beyond the abscondment of health workers from IDP camps, findings also revealed that conflicts have also affected the IDP accommodating host communities. Many doctors and nurses also abscond from general health providing centres such as general hospital and maternity centres. The following information is provided about Doctor and nurses migration in conflicts ravaged areas (Table 2). Table 2 indicated a sharp drop in the number of doctors and professional nurses/midwives in some general hospitals. Apart from the fact that these professional health workers were largely inadequate, many of them were leaving their duty post as a result of conflicts. For example, the General Hospital in Bundi- Yadi which has 3 medical doctors, lost three of them by 2014. In a similar vein, the total number of midwives in that same hospital dropped from 33 to 25. The same can be said of Damaturu, where the total number of Nurse/midwives also plummeted to 27 from 104. Although the number of medical doctors in Potiskum increased from 11 to 86, the same cannot be said of Damaturu which recorded a drop to 17 medical doctors from 24. This portends serious implications for global quality health services, not only for IDPs, but also for host communities offering support to IDPs. Even National Youth Service Corps medical doctors serving the nation under a compulsory national service are not spared of this fear of attacks and other unsuspecting dangers to their lives.

1 Information was sourced from the Yobe state Human Resources Information system (HRIS), 2017.

2 The information was given by an informant participant of the research 2018

Under the above scenario, IDPs population and some members of the war-ravaged communities who require serious medical attention were left unattended to. Many of them lost their lives. Some have become mentally deranged in the course. Following this, Sambo (2017) confirms that 98 percent of IDPs suffer from irregular medical care. This finding is also in consonance with the Human Rights Watch (1998) observation which noted that children and women suffer the most serious effects of minimal and irregular medical care: 80 percent of IDP children do not receive social security or vaccination. More so, the use of quack by IDP management agencies not only put the lives of IDPs in danger, but also undermined quality health service (Olagunju, 2006). No wonder that the Women Commission for Refugee Women and Children (1999) has also validated the claims that malnutrition, respiratory illnesses, diarrhoea, parasitic disease and sexually transmitted diseases are indicators of the extreme fragility of IDP living conditions.

In the absence of health infrastructure, especially those affected by the impact of conflicts, there are high risks of mental health problems and post-traumatic stress disorders (PTSDs) which are sometimes a consequence of depression and loss of dear ones (Mujeeb, 2015; Getanda et al., 2015). Following the above, other mental health issues such as anxiety, disorder and psychological stress often result in harmful health behaviour such as uncontrolled alcohol intake and smoking. These unguided lifestyles often exacerbate hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetics and cancer among other life-threatening diseases (Roberts et al., 2012).

Related to the above is the Issue of Brain Drain, the absence of effective positive health delivery environment has often affected quality health service for IDP. The increasing brain drain which underscores migration of quality health workers and practitioners in search of favourable working condition devoid of conflicts and instability. Although it has been argued in some quarters that brain drain is the result of greener pasture and economic incentives, the point however is that most health care giver in the North Eastern part of Nigeria leave their job largely due to the consequence of conflicts and insurgency. According to the broad spectrum of opinion from informant sources, ‘many medical doctors and nurses, resigned, some even abscond and travel abroad not only because of economic interest but largely due to the fear of losing their life’s in the face of the ranging boko haram insurgency’”

IMPACT OF CONFLICT ON MOVEMENT RESTRICTIONS

Linked to the issue of fear is the restriction and movement challenges faced by health workers. It was revealed that many health workers apart from the fact that they are absconding their post, also had challenges moving from one camp to the other to address the health concern of IDPs. In many of the war-torn areas, the tendency is for insurgents to lay ambush, invent roadblocks, checkpoints and prevent people from moving from place to place, especially health and community workers. More so, counter insurgency has also become big issues here as curfew and travel restrictions place health workers at the behest of discharging their responsibility. Medical doctors were sometimes called for emergency, but restriction of movement and fear of being a victim often discourage them from showing up. Sometimes, there had to be special arrangement with security personnel or even insurgents to allow health workers to move freely to do their work (Nigeria Medical Association, 2015).

Although some categories of development workers, including health workers, are sometimes provided with ‘road pass or identity recognition’, many of the health workers often avoid exposing their identity not only to insurgents, but also to security officials. As stated by one of the research informants, ‘health workers access to IDPs are sometimes cumbersome as insurgents and even government security places them on serious security check and surveillance’. As stated by one of the health workers interviewed “putting on your identity is not a license, you are vulnerable to the insurgents, and not carrying it at the same time makes you a suspect to the security personnel”. This lack of trust often has serious implications for health workers to do their work without encumbrances. In situations where health workers are having difficulty accessing IDP camps, transiting of drugs to IDP Camps often becomes quite impossible, as vehicles conveying drugs are also subject to undue routine checks and confirmations, thereby delaying their time of delivery and use. These factor had been responsible for the recent polio outbreak at the IDP camp in Borno putting the lives of many children at stake. As evinced by the Borno state Government Report in 2016, the lack of access to IDPs and some local communities were responsible for the outbreak of communicable diseases in conflicts affected area in the North Eastern part of Nigeria. According to the report: A joint UN road mission to Damboa in Borno state aiming to assess available health services for the IDPs and host communities and to deliver essential medicine including malaria modules enough to treat 5000 people for three months was aborted. Polio vaccination activities were also delay in reaching Ngala and Bala/Balge due to escort limitations. These constraints also make it hard to conduct quick investigation and response to alerts of suspected cases of communicable diseases in affected

areas.

IMPACT OF CONFLICTS ON HEALTH INFRASTRUCTURE

Findings also revealed that insurgents’ deliberate target of government institutions, especially health facilities such as sub-health post, maternity centres, and hospitals have also undermined global quality health service. Some health infrastructure and facilities have been attacked, with insurgents carting away valuable drugs, hospital equipment, ambulances and vehicles. This has undermine quality health services as some of these facilities meant to be used for in-house facilities for keeping materials and addressing emergency cases becomes unavailable (Ager et al., 2015). In Borno for example in was observed in a survey that about 593 health facilities, including 2 tertiary hospitals, 16

secondary hospitals, 113 primary health care centres, 239 primary health care clinics, 219 health posts and 4 IDP camp clinics exists in Borno. Out these facilities, 246 of were either destroyed or functional (Borno Health Sector Bulletin, 2018). This translates to 42% of the functional healthcare facilities in the state. Out of the 593 health facilities highlighted above, 99 (17%) were partially functional, and 81 (14%) were non-functional (Borno Health Sector Bulletin, 2018).

In the case of Adamawa, of the 1120 facilities surveyed, which include 1 tertiary hospitals 28, secondary hospitals 363, primary health care centres 336, primary health care clinics 389 and 3 IDP camps. Only, 516 of the total amounting to 46% were destroyed (Borno Health Sector Bulletin, 2018). Of the 379 health facilities that were not fully destroyed, 240 (63%) were partially functional, and 61 (16%) were non-functional (Borno Health Sector Bulletin, 2018).

This destruction and non-functionality of health facilities are consequence of conflicts and long term abandonment due largely to the impact of conflicts. Indeed, many health workers often vacate their duty post or abscond outright, because of the fear of been victim of attack. As stated by one of the research participants who is a health worker with one of the IDPs in the North “every night we vacate the IDP camp and take refugees somewhere, we were advised by the security officers to do so, because of the fear that the insurgents might make us ready-made targets”. Indeed, some health infrastructure such as hospitals and local clinic has had to be closed down until normalcy is restored. Movement for health workers and patients to access health infrastructures and facilities has been a principal problem due to delays and limitations imposed by the security services (the Joint Task Force, JTF). (Ager et al., 2015).

IMPACT OF CONFLICT ON SERVICE PROVISION

In the review of the report of the United Nation Mission to IDP countries, German Technical Cooperation (GTZ) as

well the technical report on the Assessment of the Impact of Conflicts on the Situation of Children and Women in a conflict affected districts, it was demonstrated that frequent attacks on communication facilities, transportation blockades and threat to service providers are most likely to affect health service delivery. This submission is a reflection of the shortage of drugs and commodities, and lack of easy access to IDP camps by health workers and their administrators. For example, an informant health worker reported a case of 50 years of Fulani who died because of urinary tract problem owing to lack of access to the camp by health workers. Insufficient access to health services are the principal hiccups in providing quality health services for IDPs and host communities, particularly women and children. The predicament of pregnant women experiencing complications at the time of delivery are worse, as the lack of maternal support or inadequate medical attention often leads to death or still birth. Even where they had safe delivery, sometimes children are not covered by an immunization programme.

1 Informant interview with some local traditional rulers in 2018.

2 Information provided by one of the research informants in Borno, 2017.

3 Information provided by one of the research informants in Borno, 2017

4 Personal interview with a health worker in Maiduguri in 2017 who decided to be anonymous.

FINANCIAL CONSTRAINT AND INADEQUATE FUNDING

The lack of adequate funding of IDPs is also a serious problem for the global quality health service. As a consequence of conflicts, the health sector requires additional financial support to cushion the increasing effect of conflicts because of volumes of casualties and emergency requiring medical attention. In most of the IDPs, there are inadequate funding for food and drug supplies. This is in addition to the overarching funding contribution to the Joint Task Force (JTF) security operation. As a matter of financial pressure, medium and longer term development health projects such as building of hospitals and facility construction were postponed for emergency matters. Conscious efforts to ensure financial arrangement covering emergency situations are also lacking, and many of these situations results in death, permanent disability and mental disorder of IDPs who cannot cope with the deteriorating health situation. This finding is convergent with the studies of Olagunju (2006) which stresses that Nigeria’s government does not have adequate funding and machinery in place to address IDPs related problems. Even the organizations established to handle such challenges are also handicapped and have been largely ineffective.

This study has examined the impact of conflicts and insurgency and their implications for the delivery of global quality health service for the internally displaced persons in Nigeria. In the current context of increasing conflicts and insurgencies, global quality health service has remained fragile and unattainable, with its attendant implications for IDPs. While it can be argued that the combined effort of the government and the host community have been crucial in providing succor to the IDPs, perennial insurgencies, such as the Boko Haram, farmer-herder’s and the Niger Delta militancy have undermine efficiency of health services to IDPs due largely to a host of factors that impede their satisfying performance. These factors include impact of conflict on migration health workers, movement restriction, health infrastructure, service provision and financial constraint among others. It is stressed that in the absence of global quality health service, IDPs and refugee crisis is unlikely to abate and the consequence for renewed conflicts and the implication for human security, especially the internally displaced persons in Nigeria. To ensure global quality health service, it is recommended that:

(1) Government should ensure strong national health care policies and strategies in line with the World Health Organization and World Bank objectives of achieving quality health service in the year 2030.

(2) Health professionals and trained community development workers should be engaged to work with (IDPs) in camps; especially those with delicate situations such as traumatized internal displaced persons to help them find durable solutions.

(3) Notwithstanding, there should be improvement in the confidence of health workers in conflict situations. Such confidence building should ensure basic orientations on conflict and strategy; mitigation and negotiation skills.

(4) Conscious effort must also be put in place for formative and summative evaluation to ascertain the impact of medical attention on the quality of health services offered to IDPs, bearing in mind adjustments and limitations imposed due to conflicts and lack of adequate supervision and monitoring.

(5) There should be proper orientations of security forces on the Geneva Convention and other international resolutions practices governing rights and duties of health workers and IDPs. Such feedback promotes interpersonal communication skills, respect for human values and human rights.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

The authors will like to acknowledge the support of the Tertiary Education Trust Fund (TETFUND), an initiative of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, for its support to undertake this study through the Institution Based Research (IBR) Intervention.

REFERENCES

|

Addison T (2003). From Conflict to Recovery in Africa. New York: Oxford University Press.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ager AK, Lembani M, Muhammad A, Ashir MG, Abdulwahab A, Pinho HD, Dellobele P, Zarowsky C (2015). Health Service Resilience in Yobe State, Nigeria in the Context of the Boko Haram Insurgency: A System Dynamics Analysis Using Group Model Building. Conflict and Health 9(30):1-14.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Alozioenwu HO (2012). Contending theories on Nigeria's security challenge in the era of Boko Haram insurgency. Peace and Conflict Review 7(1):1-8.

|

|

|

|

|

Amnesty International (2010). Abused and Abandoned, Refugees Denied Rights in Malaysia.

|

|

|

|

|

Babbie E (2008). The Basics of Social Research (4th Ed.)Belmont, CA: Thomson Higher Education.

|

|

|

|

|

Bakut SO (2007). Conflict Dimension and Sectarian Crises in Nigeria. Benin: Montana Publishing.

|

|

|

|

|

Bayart JE, Ellis S, Hibou B (1999). The Criminalization of the State in Africa. Oxford: James Currey.

|

|

|

|

|

Borno State Ministry of Health (2016) North Eastern Nigeria Humanitarian Response. Borno State Health Sector Bulletin. No 1. September.

|

|

|

|

|

Borno State Ministry of Health (2018) North Eastern Nigeria Humanitarian Response. Borno state Health Sector Bulletin. No 1. February.

|

|

|

|

|

Brookings (2006). Internal Displacement. LSE Project. Arlington. pp. 1-12.

|

|

|

|

|

Burke MB, Miguel E, Satyanath S, Dykema JA, Lobell DB (2009). Warming Increases the Risk of Civil War in Africa. Proceedings of the National Academic of Science 106(49):206-704.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Canci H, Odukoya OA (2016). Ethnic and Religious Crisis in Nigeria: A specific analysis Upon Identities (1999-2013). African Centre for Constructive Resolution of Disputes (ACCORD) AJCR 2006/1.

|

|

|

|

|

Chabal P, Daloz J (1999). African works: Disorder and Political Instruments. London: James Curry Publisher.

|

|

|

|

|

Dougherty EJ, Pfaltzgrate Jr LR (1990). Contending Theories of International Relations: A Comprehensive Survey, second edition. New York: Harper and Row Publishers.

|

|

|

|

|

Dowd C, Drury A (2017). Marginalisation, Insurgency and Civilian Insecurity: Boko Haram and the Lord's Resistance Army. Journal of Peacebuilding 5(2):136-152.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Getanda EM, Papadopoulos C, Evans H (2015). The mental health, quality of life and life satisfaction of internally displaced persons living in Nakuru County. Kenya. BMC Public Health 15:755.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hellesen P (2008). Counterinsurgency and its Implications for the Norwegian Special Operations Forces. A Thesis for the Naval Post Graduate School, Monterey, California. June.

|

|

|

|

|

Herskovits G (2012). Conflicts and Boko Haram Insurgency in Nigeria. London: James Currey.

|

|

|

|

|

Human Rights Watch (1998), War without Quarter, Colombia and International Humanitarian Law, Human Rights Watch, New York, USA.

|

|

|

|

|

Ibanez MA, Moya A (2007). Vulnerability of Victims of Civil Conflicts: Empirical Evidence for the Displaced Population in Colombia. World Development 38(4):647-663.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

IDMC (2012). Resolving Internal Displacement: Prospects for Local Integration. The Brookings Institution, London School of Economics Project on Internal Displacement.

|

|

|

|

|

IDMC (2015). Nigeria IDP Figures Analysis2015. Retrieved from

View 17th December 2018.

|

|

|

|

|

IFRC World Disaster Report (2000). World Disaster Report-Focus on Public Health. Retrieved on the 17th December 2018 from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Integrated Regional Information Networks (IRIN) (2007). NIGERIA: Flooding, rainstorms force people from homes in the north. 30 August.

|

|

|

|

|

Koehn PH (2006). Globalization, Migration Health, and Educational Preparation for Transnational Medical Encounters. Global Health 2(2):1-16.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ladan MT (2007). Migration, Trafficking, Human Rights and Refugees under International Law: A Case study of Africa. Ahmadu Bello University Press, Zaria Nigeria.

|

|

|

|

|

Lewis P (2002) Islam, Protest and Conflict in Nigeria. Washington: Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) Africa Notes no 10.

|

|

|

|

|

Martin AS (2018). Internally Displaced Persons and Africa's Development. Benin: Afreb Publishing.

|

|

|

|

|

Midlarsky IM (1975). On war, Political Violence in the International System. New York: The Free Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Mooney E (2005). The Concept of Internal Displacement and the Case for Internally Displaced Persons as a Category of Concern. The Refugee Survey (24):9-26.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Muhammad AM (2012). North East and the Paradox of Boko Haram. Borno: Centrum Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Mujeeb A (2015). Mental Health of Internally Displaced Persons in Jalozai camp, Pakistan. International Journal of Social Psychiatry (61):653-659.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

The Nation (2016). Internally Displace Persons and Emergency Response in Nigeria. June 25th.

|

|

|

|

|

National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) (2017). Nigeria's Unemployment Rate.

|

|

|

|

|

National Emergency Management in Nigeria (NEMA) (2015). Abuja: NEMA Responded to over 1000 Emergency Situations in 20 Months. Abuja: NEMA.

|

|

|

|

|

National Emergency Management in Nigeria (NEMA) (2016). Borno Still has 32 IDP Camps Despite Returns of some Displaced Persons. Abuja: NEMA.

|

|

|

|

|

Nigeria Medical Association (NMA) (2015) Challenge of Medical Professional Medical Practitioner in the Northern Part of Nigeria. Lagos: Maltinex Publishing.

|

|

|

|

|

Norwegian Refugee Council (NRC) (2016). 'More than 31 Million People displaced within their own country in 2016'. Geneva: IDMC global projects. Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Internally Displaced People. Retrieved from

View on the 16th May 2019.

|

|

|

|

|

Olagunju O (2006). Management of internal displacement in Nigeria. Unpublished thesis. Brandeis University. Retrieved from

View on the 17th May 2019.

|

|

|

|

|

Olukolajo MA, Ajayi MA, Ogungbenro MT (2014). Crisis Induced Internal Displacement: The Implication on Real Estate Investment in Nigeria. Journal of Economic and Sustainable Development 5(4)39-48.

|

|

|

|

|

Oshagae E, Suberu R (2005) A History of Identities, Violence and Stability in Nigeria. CRISE Working Paper NO 6 Oxford: Centre for Research on Inequality, Human Security and Ethnicity. Retrieved from

View. November 16th 2018.

|

|

|

|

|

Owoaje ET, Uchendu OC, Ajayi TO, Cadmus EO (2016). A review of the health problems of the internally displaced persons in Africa. Nigeria's Postgraduate Medical Journal 23:161-71.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Porter M, Haslam N (2005). Pre-displacement and Post-displacement Factors Associated with Mental Health of Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons: A Metal Analysis. International Journal for Equity in Health 294(5):602-612.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Richard J (1999). Autocracy, Violence and Ethno-Military Rule in Nigeria. In: J Richard(Ed), State, Conflicts and Democracy in Africa. Boulder, CO: Lynne Renner.

|

|

|

|

|

Roberts B, Patel P, McKee M (2012). No communicable diseases and post-conflict countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 90:2A.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sambo A (2017). Internally Displaced Persons and their Informational Needs. University of Nebraska, Lincoln3 (7):1-15.

|

|

|

|

|

Save the Children (2000). War Brought Us Here: Protecting Children Displaced within Their Own Countries, London, Save the Children.

|

|

|

|

|

Schmidt A (2000). Thesaurus and Glossary. London: FEWER.

|

|

|

|

|

Siegel LJ (2007) Criminology: Theories, Patterns and Typoligies.11th edition. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

|

|

|

|

|

Tay AK Rees S, , Chen J, Kareth M, Lahe S, Kitau R, David K, Sonoling J, Silove D (2015). Association of Conflict-Related Trauma and On-going Stressors with the Mental Health and Functioning of West Papuan Refugees in Port Moresby. Papua New Guinea 10(4):125-178.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

This Day (2008). The Challenge of Quality Health in IDP Camps, Nigeria. April 17th.

|

|

|

|

|

United Nation Development Programme (UNDP) (2018). Human Development Indices and Indicators: 2018 Statistical Updates. Retrieved from

View 17th December 2018.

|

|

|

|

|

United Nation office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) (2007). Retrieved from

View April 20th 2017.

|

|

|

|

|

United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) (2011). Global Overview: People Internally Displaced by Conflicts and Violence. Retrieved from View on 10th June 2015.

|

|

|

|

|

United Nations Office for West Africa (UNOWA) (2007). Urbanization and Insecurity in West Africa. Population Movements, Mega Cities and Regional Stability Internet.

|

|

|

|

|

Women Commission for Refugee Women and Children (1999). Annual Report 1999.

|

|

|

|

|

World Bank (2018). Delivery Quality Health Service: A Global Imperative for Universal Health Coverage.

|

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (2008). Health Action in Crises (WHO/HAC). Highlights. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

|

|