Globally, there has been a campaign to promote participation of females in the entire development agenda in general, but specifically in the higher education sector. Public universities in Uganda have attempted to ensure that female stakeholders are given a platform to participate in leadership and governance of their respective universities, though still seemingly scanty. The study therefore explored perceptions of female student representative participation in leadership on public university councils in Uganda. The Ladder of Citizen Participation was utilised to get meanings and understandings from the perceptions regarding levels of participation. The study deployed a phenomenological research design with unstructured interview, transect walks and letter writing methods and a two-level narrative analysis technique used to capture plots and themes from the narratives. Findings reveal that female students do not have sufficient ground to effectively participate in leadership and governance due to several constraints. The revealed constraints include lack of sufficient leadership capacity, insufficient resources and gender stereotypes. It is therefore concluded that participation of female student representatives on public university councils in Uganda was mere tokenism! It is therefore recommended that the higher education sector should deliberately support female students towards effective participation in leadership. This can be done through building their capacity in leadership and governance and providing sufficient resources to enable them easily pursue their leadership and governance mandate, among others.

McCarren and Goldman (2012) promote that the world over there has been a lot of stereotyping on feminism in leadership positions across the board. However, various scholars posit that women display a lot of attributes in leadership, reason why they should be encouraged to effectively pursue leadership and governance. Mohr and Wolfram (2007) assert that women’s feminine leadership style could be rewarded because it is in line with gender stereotypic expectations. This positive effect may be mitigated by the mismatch that their role as leaders presents with respect to gender role expectations: even today, the leadership role is still conceived as being a male role, which adds to the notion of perceived incompetence of women in leadership.

Government of the Republic of Uganda has over the years promoted affirmative action especially to give equal opportunities to the different gender groups in all aspects of development, not sparing the education sector (RoU, 2007). At a global level, there has been recurring debate about the issue of student representation in higher echelons of universities, particularly university councils. While there was a clear lack of student representation at the highest level of the universities, gender issues came to the fore in the sense that women representation has always been ignored even when student participation issue was being addressed.

The Universities and Other Tertiary Institutions Act (UOTIA) No. 7 of 2001, Section 38 considers a need to have at least one female student representative on all public university councils in Uganda (UOTIA, 2006). Again, in 2007, the Ministry of Gender, Labour and Social Development developed a Gender Policy, which reaffirmed the need to have female students participating in all sectoral development processes, including education sector (RoU, 2007).

Literature shows that there is still a challenge on effective women leadership especially in higher education (Kent et al., 2010; Growe and Montgomery, 1999; McCarren and Goldman, 2012). There are several barriers that prevent women from achieving their leadership expectations (Sperandio and Kagoda, 2010). These scholars assert that these barriers include male domination in many roles, heavy domestic workloads and reproductive roles for women, lack of self-esteem and self-limiting practices, and a lack of sufficient qualifications in some cases (Sperandio and Kagoda, 2010).This picture provides a comprehensive situation about the barriers that women leaders face in terms of how other gender groupings view women and their possible role in leadership responsibilities. These stories assist us in understanding how female student representatives on public university councils may be viewed by fellow members and other stakeholders in this structure. Similarly, these women leaders could be facing similar challenges which may be affecting the way in which they perform their duties as representatives of students in university councils.

However, despite so many years of debates about the need to address this issue, there is still limited literature on participation of female students in leadership of universities in public universities of Uganda and some parts of the world. Studies have investigated the general picture of women’s participation in leadership and governance, without necessarily focusing on female student representatives in governance structures of the universities (Appelbaum et al., 2015; Hora, 2014; Batliwala and Pittman, 2010). Other studies have dwelled on investigating women’s participation in leadership of higher education institutions at faculty level, which mainly has appointed officers in the universities (Airini et al., 2011; Growe and Montgomery, 2003). This also tends to imply that such studies left out a unique group of leaders at corporate level, the female student representatives on university councils. Neil and Domingo (2016)also agree with the fact that the majority of studies look at interventions to develop grassroots women leadership or to help women get into formal political positions, unlike the case for female student representatives in higher education institute leadership. The study therefore aimed at exploring the lived experiences of female students who are members of public university councils in Uganda.

Ladder of citizen participation

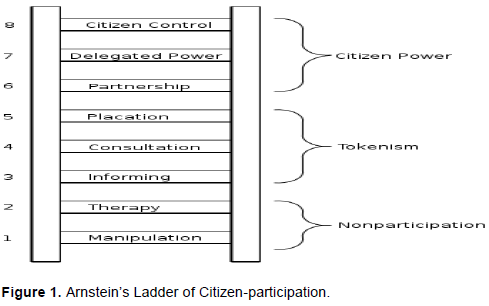

The Ladder of citizen-participation theory was deemed relevant in this study because it aimed at understanding the levels of participation of female student representatives in public university councils in Uganda.

The use of this theory enables accurate descriptions of their level of participation in terms of the strand of participation as described by Arnstein (2004). Arnstein (2004)asserts that empowering people enables submission of their views to higher authorities, but only through ensuring effective participation in leadership. The female student representatives required empowerment in order to execute their leadership mandate.

In Figure 1, Arnstein (2004)postulates that if leaders are to participate effectively, the ladder gives a three-strand pattern with eight rungs where the first strand of non-participation comes with manipulation and need for therapy. Therefore, in a nutshell, the first strand is characterised by non-participation. The second strand is tokenism, and comes with leaders accessing some information; undertaking consultations; and placation. Therefore, participation in the second strand shows some improved level of participation where stakeholders (student representatives in this context) have access to some information and are consulted on some important issues affecting the institution. The third strand is citizen power, and is characterised by full empowerment of stakeholders and comes with leading through partnerships, exercising full delegated power and having a lot of control. The Ladder of Citizen Participation helped the study to get an understanding regarding the magnitude of empowerment of female student leaders that enabled them to execute their leadership mandate.

Guaraldo (1996), in support of the Ladder for Citizen Participation, promotes the notion that leaders need empowerment if they are to influence decisions which affect them. Accordingly, Hora (2014)advances that when leaders have the power, they will be able to influence decision-making. This also relates to the postulations under the Ladder for Citizen Participation, which posit that participation is key for effectiveness of leadership and representation. Female student representatives therefore required a lot of empowerment if they were to pursue their leadership mandate. Therefore, the Ladder for Citizen Participation supported the understanding on effectiveness of their leadership through getting meaning from how public universities provided space for the female student representatives to present students’ issues for resolution by the respective councils.

The Ladder of Citizen Participation presupposes that participation of people in leadership leads to enhanced empowerment (Arnstein, 2004). In a related argument, participation in leadership and governance may be dictated by the degree of involvement in decision making and whether there is effective information flow (André et al., 2012). This relates to Guaraldo (1996)’s argument that for effective results, leaders ought to be well empowered in order to influence decision making. At higher rungs on the Ladder of Citizen Participation leaders get more involved in decision-making. The Ladder of Citizen Participation therefore assisted the study to get a clearer understanding from the stories captured from the participants about magnitude of opportunity that was given to them to contribute during council deliberations and to follow up implementation of the resolutions. The exercise of power clearly corresponds to the leader’s ability to satisfy needs of those they lead and implementation of the interests of their social groupings (Hora, 2014). The argument also advances the participation principle if there is to be effective leadership. According to Collins and Ison (2006), the ladder illustrates the essentiality of participation as a power struggle trying to move up the ladder for more leadership effectiveness. This implies that female student representatives ought to struggle to get more empowerment and influence in the decision making process so that the issues forwarded by fellow students are actually resolved. However, this differs from context to context since there is no one best way to ensure participation (Connor, 1988). The Ladder of Citizen Participation therefore facilitated the study while trying to draw meaning and understanding of how female student representatives on public university councils were given a platform to participate in university leadership. It is a fair expectation that in some instances due to leadership styles and prevailing situations, the levels of participation of these women leaders would vary from university to university. The use of this theory described their level of participation in terms of the strand of participation.

Participation in decision-making influences and enhances the process of addressing people’s needs through allocation of resources and thus, their improved well-being (Paper, 2013). The Ladder of Citizen Participation therefore supported the process of understanding the levels of different female student representatives’ participation in leadership and governance. This, in the different contexts of life-world of these women leaders, also gave meaning to effectiveness of the different female student leaders as influenced by the participation platform that was extended by the respective public universities. Similarly, Restless Development (2013), in a related argument, posits that it is important to foster participation of youths in leadership and governance since it promotes the concept from grassroots level. It also builds experience and knowledge of participatory governance from a young age and from the lowest level of community decision-making. In the context of this study, the Ladder for Citizen Participation was deployed to give a better understanding about the linkage between participation levels of female student representatives and effectiveness of their leadership mandate. From their stories, meanings were derived from such participation levels on the female student representatives’ leadership capacity. The higher the female student representatives on the Ladder of Citizen Participation, the more the opportunity to pursue respective leadership mandate due to higher participation levels.

Study participants had mixed reactions regarding their participation in the pursuance of leadership and governance at their respective universities. While they all indicated that they have space to pursue their leadership and governance mandate, the female student representatives on public university councils in Uganda had reservations on being given sufficient space to deliver student expectations. The study participants raised concerns regarding their ability to participate in leadership, insufficient platform to participate and insufficient capacity to pursue leadership mandate.

Ability to participate

In order to confirm that the female student representatives were able to undertake their leadership mandate, participants in the study were asked to comment about how they pursued their leadership mandate and levels of satisfaction from their student counterparts. Anne indicated that she forwarded student issues on the floor of council and that some of her debates won approval of the other council members. She explained:

I thank God for the tremendous services that I rendered to the students and the entire community of the University as a female students representative on the University Council. During Council meetings, several of my debates won approval of the members of Council and the Chairman, for example when a committee of technology brought a report for the approval of the increment of technology fees, I strongly objected giving reasons why the increment was not genuine. Upon these debates, members including the Chairman did not approve this and the committee members were asked to go and revise their report. I also contributed in making council resolutions for example, payment of lecturers, early release of examination results, election of the new Vice Chancellor and many other duties executed by the University Council, which will always remain on record and am so grateful to God (Anne).

Female student representatives observed that they were able to pursue their leadership and governance mandate at respective universities. They reiterated that they actually provided good representation of their fellow student views to the university council. Irene also explained:

I believe that I make a good representation of students on the University Council because I always take up views from students, which gives them a voice on the highest decision-making organ in the University. I always consulted them, asked for their opinions on various issues that affect them. There have been a lot of issues which students felt should be resolved at Council and I, as their representative have tried my best to make the best presentation on the floor of Council(Irene).

The female student representatives further noted that their constituents, the fellow students, showed satisfaction from their leadership, which to some extent displayed their participation in university leadership and governance. Anne observed: students usually indicate their satisfaction with my representation on the University Council especially appreciating where I stood my ground for their cause. On several occasions, the Vice Chancellor describes me to fellow students “a young girl that stands in the gap for thousands of students at the University” and I believe the students become happy with my effort.

This implies that female student representatives in some occasions attempted to present students’ issues before council for consideration and they were given platform to present these views. Pauline also reiterated that from successful pursuance of students’ issues with council, the students showed satisfaction with the role of their representatives. She explained:

As a female student representative to the University Council, I have good memories as I executed my mandate. This was exhibited with the respect I got from students; for example the students have a positive attitude about Council members, hence making positive comments that have built my self-esteem about leadership (Pauline).

Relatedly, Jesca reiterated that fellow students showed satisfaction with her leadership. She also explained: “Another wonderful thing is that I got to relate with different students that encouraged me with amazing comments about my leadership and I must say that they have built my self-esteem and that is a fantastic thing. Many say that I inspire them because of my discipline and level of commitment”.

This illustrates that the female student representatives in university councils actually endeavoured to pursue their leadership and governance mandate. It to some extent indicates that they participate in the leadership and governance of their universities. Relatedly, Stecia explained: “Generally speaking, students were showing satisfaction about my leadership and representation at Council. During feedback sharing, it was obvious that the students appreciated my effort to submit their issues to the University Council, where several serious matters were actually resolved”.

Anne further confirmed her success during participation in the debate of the university council, where she was listened to and her proposals accepted. She explained:

The Council Chairperson always gives me an opportunity to forward students’ issues on the floor of Council. I have been able to undertake my representative role through the several issues presented during budget discussion, which several times is amended to consider student activities and issues. Several students’ issues that I have brought before Council have been resolved. For example, when non-teaching staff laid down their tools through a strike, the libraries were locked and students were not getting the services due to them. When Council sat to resolve the issue, I put up a spirited fight until the issue was resolved amicably. Then another case was when the lecturers went on strike and the students missed their examinations thus, their future not well determined. The University Council intervened through lobbying for funds from the outside and the university resumed its work (Anne).

Female student representatives on public university councils in Uganda reiterated that in the pursuance of their leadership mandate, their focus was on serving their fellow students. This attribute of a leader would definitely promote effective participation in the leadership and governance arena since the people being led would easily endorse their leaders. This explains the concept of servant leadership being a key contributing factor towards enhanced participation of female student representatives on public university councils in leadership and governance. According to Gregory et al. (2004), a servant leader focuses on the people that are led unlike the focus on the self. The feeling of being a servant leader is basically natural where one believes that they truly want to serve others first before leading them (Bowman, 2005). Mccann and Sparks (2018)argue that servant leaders begin with the natural feeling that they want to serve first before taking on leading. The scholars promote that a servant leader should always care for the people that they lead in order to deliver solution to their prioritised needs. From Anne’s experience, it should be noted that she had gone through a period of availing herself to serve her colleagues in the pursuance of leadership. In a letter that she wrote to a friend, Anne expressed her experience as a servant leader as follows:

I thank God for the tremendous services that I rendered to the students and the entire community of the University as a female students representative on the University Council. During Council meetings, several of my debates won approval of the members of Council and the Chairman, for example, when a committee of technology brought a report for the approval of the increment of technology fees, I strongly objected giving reasons why the increment was not genuine (Anne).

By being effective listeners, the leadership practices of female student representatives were underpinned by values of servant leadership. Spears (2010)described a servant leader as one who listens receptively to the ones that are led. Anne further explained: “I was able to relate with my fellow students through the good services that I rendered them since I had pledged service with love. In this I was able to defend their rights and to advocate for their welfare”.

Mccann and Sparks (2018), for instance, argue that in order for leaders to be effective, they should be good listeners. Mccann and Sparks (2018)further argue that people would always appreciate leaders who listen to them carefully, trying to understand what they say while they would not be offended when they are asked for clarity. Leadership on a very large extent depends on interactions between the leader and their subjects since this is what enables relationship building. The argument advanced by the above-mentioned scholars promotes the view that if one is to be a good leader, there is a need to do more listening than talking. In Pauline’s narratives, she clearly articulates the view that one of her strategies to succeed in her leadership role was to give audience to the fellow students in order to capture their views while also giving them well founded feedback. She explained:

In order to effectively interact with my fellow students I always undertake my research well to remind myself of their issues and how far they have been responded to. Often, the students look at us negatively especially due to unresolved issues that they may have previously raised. I have always interacted with students through talking to them both as individuals and in groups in a humble manner. I always use these interactions to give the students feedback, while I also capture their views on prevailing circumstances. My interaction with students is always nice since we listen to each other (Pauline).

Effective participation in leadership and governance was also illustrated by the female student representatives since they focused on results. It is important leaders have goals that they want to achieve through their leadership practices. Therefore, results based kind of leadership becomes important. Obiero (2012)advocates the view that if students participate in leadership and decision-making processes at the university, it will be very easy to see them identifying with outcomes of such processes, thus minimises student related administrative problems. Irene was such a leader, who seized the opportunity to participate in the university decision-making process. Along the way, by taking such an approach, she would be giving power back to fellow students, and she believed that it is the only way her leadership would yield positive results. By sharing governance, students feel more positive about university goals and objectives (Obiero, 2012). Irene was given the opportunity to deliberate before the University Council like she explained:

We (the Guild President and I) were respected by fellow Council members; any issue that was to be discussed and passed, our views as student representatives was keenly sought at the Council. Every time I received invitation for council meetings, I consulted my fellow students on what they think I should present on table, and I would do exactly that. This eased my work as I did not always have to figure out everything on my own. Students also felt I always gave power back to them (Irene).

The narratives further indicate that Irene is such a proactive student leader amidst a lot of opposition from fellow Council members. Klemp and Consulting (2008)posit that leaders need to have a skill of being able to initiate effort through being proactive. By so doing, they drive change through taking risks so as to shape things. The argument concurs with Irene’s narrative which stated:

…every time I go to attend Council meetings and try to present such issues, there are only a few council members who may stand with me, saying ‘let us give the students what they deserve’, but there are those who will be against the whole idea, which causes a state of friction with them. At times I even observe a change in mood of some of the Council members, who may be against the issues that I present before Council. …. However, the Council Chairperson is very cooperative since she has a passion for students and she is a mother herself. Whenever I put up my hand to make a contribution before Council, the Chairperson would always be quick to give me the audience. This has also helped me in the pursuance of my leadership role as a female student representative

According to Klemp and Consulting (2008), if leaders are to be effective they definitely have to set direction and focus on results. Irene is one such leader who, from the narrative, indicates that she has performed her role as a female student representative focusing on achievement of results. She explained; “I, together with the Guild laid strategies to have several of the issues resolved and implemented by Council and management respectively”.

Caspar and Hall (2008)advance the view that for leadership to be effective, the leaders need to be responsive to their followers’ needs. Jesca narrated a story that during her tenure as female student representative in the University Council, she prioritised students’ needs by ensuring that such needs were actually responded to. She explained:

I have been very responsive to students’ issues by presenting them to the respective responsible parties. I have been very much in contact with the Deputy Principal who is also a member of the Council. Since we have outsiders on Council, I do not present some very sensitive matters there, but I engage management to have them resolved (Jesca).

Confidence of the female student representatives in public university councils further explained their ability to participate in the leadership and governance arena. Rosenthal (2012)contends that confident leaders feel the ability to make their leadership more effective, through displaying a great deal or moderate amount of power as they pursue their leadership mandate. Stecia narrates that sometimes she would face resistance from fellow council members, but she always managed to stand her ground. She explained one of such incidences:

One time when they wanted to postpone a students’ urgent request, I emphasised the urgency of the matter and yet council still wanted to leave it pending for quite some time. At that point I stood my ground in favour of students and that’s the time I remember getting quite a number of oppositions for quite a time during meetings (Stecia).

Drawing from Stecia’s narratives, it is evident that she identified herself as a rather experienced leader who had gained leadership knowledge from childhood and from family. She had over the years grown in self-confidence and she found this to be an invaluable asset in leadership position. She further reiterated that she is naturally committed to leadership and played the servant-leader. Literature (Klemp and Consulting, 2008; Rosenthal, 2012)contends that such a leader would easily gain confidence in the pursuance of her leadership mandate and yet effective leaders must have a level of confidence. If the higher education sector is to promote female student leadership, the female students need to display a level of confidence which may be gained by learning from experience.

One of the factors that influenced female student representatives’ relationships with council members was their perceptions of their leadership role. The manner in which participants viewed themselves influenced their leadership practices. Drawing from meanings that these participants attached to their actions, the re-storied narratives indicate that some of the female student leaders see themselves as servant leaders, and such a view influenced their leadership practices. For instance, Anne and Irene emphasised their servant leadership leanings and underpinnings. According to Bowman (2005)servant leadership has attributes also including healing, community and service. From Irene’s and Anne’s narratives and in keeping with Bowman’s (2005) views, the female student leaders were rather concerned about the good health of fellow students. With such behaviour of leaders, these female student representatives won confidence of fellow students, which eased their relationship with them. It created openness where students had a free environment to express their views especially regarding their own welfare as students. This implies that by practicing servant leadership, female student leaders may ensure effective pursuance of their leadership mandate.

Insufficient platform to participate

Female student representatives on public university councils noted that though they had a platform to participate in leadership and governance of public universities; they faced some huddles. They noted that some of the student demands required funding, which the respective universities would not be able to provide. Anne explained:

I have faced some challenges as I executed my role as female student representative in the University Council. The biggest challenge has been insufficient funding, yet most of the submitted student issues would require money to have them implemented. For example, when we lobbied for the construction of incinerators for the ladies’ sanitation, it required a lot of money; procurement of buckets as an option had to wait for some time due to absence of funds; and it only came to pass the previous day. The university, due to insufficient funding, prioritises issues, usually to the detriment of student issues, which are not considered as fast as expected (Anne).

Stecia also noted that on several occasions student issues were not considered at university council due to lack of support from fellow council members. She explained: “at times I met huddles during Council deliberations when fellow members never supported the student issues that I submitted”. Effective participation of the female student representatives in leadership and governance of their universities was also affected by tainted relationships with other university leaders. In some instances university top management would not extend the due recognition to student leaders, which rather made it difficult for the female student leaders to pursue their mandate like Irene observed:

Our relationship with management has not been very smooth through our leadership mandate. We have always stood our ground and we have always told them that every time we have an issue we make reference to approved University policies, like the students’ welfare policies. At times students pay for certain services which are not delivered by the University.

On the other hand, effective participation of female student representatives in leadership and governance of universities is affected by the students being over expectant of their representatives, like Irene explained:

Students always have 101 expectations of my leadership. First of all, they always would not want anything that may disrupt their academic programme. They come to me with issues to do, for example, with tuition payment especially penalties for late payment. I, together with fellow student leaders, find myself pleading for students who have challenges when it comes to timely tuition payment; some students are parents - I am a parent myself; they have dependents to take care of, and thus, they are always one of the last people to pay tuition! (Irene).

Pauline also indicated the challenge of too many expectations from their fellow students, which derailed her effective participation in the pursuance of leadership and governance at the university. Some of the student issues were not very easy to forward to top management and council for successful consideration. She explained:

Students are always so expectant and have a thinking that everything that they may want should be given to them! They expect me, their representative on Council to be able to bring positive consideration of their issues and nothing less. Students’ expectations are major regarding academic issues, where they never want to face barriers to their academic success. For example, one major issue that came up had to do with issuance of special examinations if one student may have had an understandable reason to miss the examinations (Pauline).

Jesca also noted that student representatives were derailed by some student issues which were rather technical and required top management intervention. For such issues, the student representatives would have limited authority to effect. She explained: “other challenges where I may not have a hand in solving include technical ones, for instance, in academic issues where a student may have missing marks. The students in this case have to follow up their issues with the lecturers until such marks are recovered”. This further illustrates that though the female student representatives on university councils desired to effectively participate in leadership and governance, they were rather derailed by the limited authority to pursue issues to their conclusion.

Female student representatives were challenged with the problem of negotiating between the higher status members of the university councils, top management and the students they represented. They encountered problems because it seemed that their concerns were not given the highest priority by the university councils and there was a need to be assertive in a situation where women have been required to be deferential to men and other council members. The female student representatives therefore had to learn how to assert themselves in a new way. What helped them to do this was the servant leader stance that they took and the help of female mentors with higher status in the committee.

Re-storied narratives of the five female student leaders indicate that although structures had been created for them to fully participate in decision-making processes of their respective public universities, practices did not automatically follow suit. In other words, leadership practice in those structures is influenced by a number of factors some of which are located within the participants themselves while others lay in the environment outside. For example, female student leaders were given a platform to exercise leadership mandate on behalf of their constituency. However, these platforms came with a few challenges which could undermine their participation and opportunities to make a contribution to leadership of public universities in Uganda.

Female student leaders that took part in this study understood their mission and that they in general had been marginalised in the past and their existence was largely ignored when decisions were being made. Therefore, when they were elected to these positions, they had developed a clear understanding that they had to fight for the rights of other students. The Ladder of Citizen Participation provided an effective analytic tool to understand and locate their level of participation in their councils. Being aware of the task at hand, female student leaders fought for the highest level in the Ladder of Citizen Participation, namely, the Citizen-Power. The Ladder of Citizen Participation Model as advanced by Arnstein (2004) advocates for full participation at Citizen-Power level. The lower level (Tokenism) is not regarded as meaningful participation and so is Non-Participation which is the lowest level in the Ladder of Citizen Participation framework. Irene can be regarded as the epitome of such ideal leader who utilised opportunity provided for them to participate in leadership and governance at her university. For Irene therefore, it meant that she had to always ready herself before interactions with fellow council members in order to effectively share students’ issues. With the platform given to Irene, there was evidence that the university encouraged participation of female students in its leadership and governance, which led to effectiveness in resolving student issues. This is in support of the Ladder of Citizen Participation, which contends the more individuals are allowed to participate in leadership, the more the effectiveness and empowerment they become (Arnstein, 2004). Furthermore, there were cordial relationships evident from the female student representatives’ narratives. Anne contends that the platform was open to participate during council deliberations.

Gathering evidence from the re-storied narratives, female student representatives on public university councils studied had a cordial relationship with fellow council members. Anne’s re-storied narratives indicated that before joining council, she had a fear that it would be difficult to relate with fellow council members in a male-dominated setting and with older and experienced members. The understandings drawn from the narrative may confirm that this particular society still had stereotypes which informed young women to never expect themselves to be part of high level leadership of an institution, especially higher education institution. Anne noted that unlike the earlier fear of facing difficult times to interact with fellow council members, contrary to her expectations, she was received with very warm welcome from the members. One of the understandings to be drawn out of the narrative is that this particular council’s membership had demystified the stereotypes that leadership was a preserve for the males only, and therefore, that other gender groupings should not be welcomed. This led to the view that even the ‘young’ female student representative were always given priority to contribute during council meetings.

Drawing from Pauline’s story about how she related to fellow council members, one is left with a feeling that unless one demands meaningful participation in leadership structures, one cannot effectively pursue one’s leadership mandates. In terms of the Ladder of Citizen Participation, Citizen-Power is the ultimate ideal wherein meaningful participation can be realised. Using this conceptual framework, coupled with servant leadership practices, female student leaders may find it easier to pursue their mandate due to servant leadership which brings leaders and followers closer together. By the level of humility that Pauline displayed in her leadership tenure as a female student leader, she would easily forward student issues to high level university organs including council until some would be resolved to the delight of fellow students.

Insufficient capacity

Pursuance of leadership and governance was not an easy sail through. Female student representatives on university councils noted that they faced a challenge of insufficient capacity in terms of resources and personal capacity in leadership, which may have led to ineffective participation in leadership and governance of their respective universities.

Regarding resource capacity, the female student representatives on public university councils indicated that they always faced a challenge to handle student issues which required financing. Stecia noted that student leaders were not being sufficiently funded, which derailed pursuance of their leadership and governance mandate. She explained that student leaders find themselves looking for money from elsewhere in order to handle fellow student issues. She noted:

The Guild never had sufficient resources, yet at times, we were required to travel on University activities in order to solve student issues. At times I would find myself digging deep into my pocket in order to respond to students’ needs for example when the DSTV subscription would expire yet they wanted to watch soccer (Stecia).

On several occasions, student issues were not being considered by university councils, reason being that they were not on agenda! This derailed effective participation of female student representatives in leadership and governance of respective universities like Anne explained:

When students’ views are not considered just because the issue was not on agenda and priority would be given to other issues on agenda - -so I would only sit and burn with a lot of passion for the dear students. Then at times there are arguments that bring about a tense environment in the Council Hall, which is not an interesting scenario (Anne).

Among challenges are poor communication, bureaucracy and red-tape, and poor time management, which can only be remedied by building the capacity of the female students in leadership. Pauline explained:

We as student leaders have had a challenge of poor communication. The flow of information from students to staff, Management and Council has not been very effective. This at times has even led to student demonstrations, yet when you analyse the situation, it might be because of misinterpretation and poor communication. Relatedly, the bureaucracy and red-tape at the University may also lead to strife since an issue may delay resolution due to the fact that it has to get approval of several role players. In such circumstances, the students look at me as a representative who has failed them in those aspects (Pauline).

Female student leadership in public universities would require the female leaders to have some level of leadership capacity due to the leadership context and amidst a chaotic environment. Some students were rather provocative and non-appreciative to their representatives, like Jesca pointed out: “there are students who are very provocative and will say things like; “this guild has done nothing for us”. These would try to get the worst out of you, yet it would only be propaganda which is not of any relevance. These challenges derail effective participation of the female student representatives in pursuance of leadership and governance of their respective universities.

The study participants also indicated a challenge of poor time management, yet time management is another key attribute for an effective leader, Pauline noted that fellow student leaders never minded about time, which was rather disturbing. She explained: “One other disappointment during my leadership tenure as a female student representative is when we go for the Guild Representative Council meetings. Deliberations may go on until very late yet it would be because of some members derailing the meeting”.

Many stakeholders still perceive women and specifically female students to have insufficient capacity, as compared to their male counterparts, and thus would better be responsible for other roles unlike leadership and governance. Jesca further reiterates that stereotyping had remained a big challenge that derailed effective participation of female student representatives in leading and governing respective universities. She explains:

To be honest, it has not been a smooth journey due to the fact that I am a female student representative. People expect so little from a female leader because they think we are vulnerable. I have been undermined before I even do something by my fellow colleagues or even people who I have just met and they also say that my position is just ceremonial and it has been challenging to change their mind-set (Jesca).

The meanings and understandings from the re-storied narratives of the female student leaders indicate that relating with fellow council members was also influenced by levels of leadership capacity and experience. Irene narrated that she found it easy to relate to fellow council members because of the opportunity to have several women leadership role models to whom she looked up to. In other words, relationships were not only shaped by what female student leaders did, but also by what they experienced as reception from their senior counterparts. Irene cited her experiences working a variety of senior people at her university such as the Dean of Students, all of whom were characterised by positive energies, and these were duly reciprocated. For instance, she narrated her story about what she had learned from several women leaders including the Dean of Students, who also happens to be the Chairperson Mothers’ Union at her church. She had found her to be a mother figure and during the time when they were preparing for elections before getting into positions they occupied as student representatives, she explained that she and others were encouraged to participate in the elections. She and others were inspired by her and their attitudes were shaped by such encounters.