ABSTRACT

The study is an investigative survey of library users’ satisfaction of library services, resources, staff conduct and impact of the library on the academic achievements of users. Qualitative data was collected from College students, faculty and library staff of two academic libraries in Ghana using questionnaires and interview instruments. The survey established that library services, information resources and the physical library environment have value because users have shown high satisfaction of them. Material lending, photocopying, library space and staff conduct recorded higher level of satisfaction. It is however recommended that academic libraries in Ghana should be equipped with online resources, adequate and knowledgeable staff, and computer systems with high broadband. Also, libraries should endeavor to market library services and resources in order to demonstrate value among stakeholders.

Key words: Library value, library impact, user satisfaction, Ghana, information resources, service quality, staff conduct.

Value creation is an exercise engaged in mostly by businesses in highly competitive industries with the aim of providing customers with a defined notion of value and the reasons to choose their products and services over that of their competitors (Zhang and Chen, 2008). The value of the academic library to its users has become a critical issue in the management of academic libraries. Librarians are now concerned with how the library services and resources benefit the students’ success, faculty and the overall institutional aim. For academic libraries to be successful, not just in these uncertain times, but in the future, Thomas (2010) succinctly stated that:

We must reinterpret our organisations to reflect contemporary needs and values. This means charting a course that remains true to principles that have guided us since the development of librarianship as a profession, but which also looks to the services we can provide that represent the greatest value for our clients.

Academic libraries are in competition with other sectors of their institutions for limited funding due to budgetary pressures (Tripathi and Jeevan, 2013) as cited in Tetteh (2018). This confirms Heider et al. (2012)’s claim that due to financial challenges, departments and divisions in higher education institutions are being examined for their impact on the overall performance of their institutions. As a result, many academic libraries too have been asked to assess the value of their resources and services to teaching, learning and research. This supports a report that due to financial constraints, libraries in developing countries have difficulty paying for e-resources (Asamoah-Hassan, 2014). Besides, the emergence of new sources of information as a result of technological innovations has negatively affected the image of libraries (Hinchliffe, 2011; Ribble, 2011) In view of these, academic libraries are being called upon to demonstrate their value in order not to become peripheral to the activities of the institutions they serve.

Germano (2011)investigating cause of and remedy for the decline value of libraries, asserted that lack of competition is the underlying factor for the decline of library’s value. However, this is not a problem with products and services, instead a lack of marketing of library’s usefulness. Libraries are therefore being called upon to establish a ‘societal, cultural and educational benefits of libraries’ that is reflective of user needs. Also, a more sophisticated marketing, customer communication and service delivery which is based on users’ needs should be employed to justify library usefulness, and demonstrate their impact and value by evaluating their resources, their services, their contribution to the realization of their institutions’ mission and goals as well as their return on investment in order to find out practical ways to ensure continuous improvement in service performance (McCreadie, 2013). According to McCreadie (2013), libraries are well perceived by faculty. In developing countries, the value of the library is determined by the quality of the collection. However, in the developed world, it has been realised that access to materials is no longer critical, rather collaborative relationship between librarians and faculty through general marketing of library’s support for teaching and research is key to demonstrating value. This confirms the assertion that library marketing raises the library’s profile among teaching and research staff (Creaser and Spezi, 2012). Besides, Albert (2014)established that libraries are able to demonstrate value when they collect data on usage and impact of their support to their institutions. This supports the claim that libraries must go beyond evaluating their services to communicate the results of the evaluation in order to demonstrate value (Hinchliffe, 2011).

The study aims to assess the value of the Ghana Institute of Journalism (GIJ) and Ashesi University libraries based on user satisfaction. This research used the explicit approaches to measure the value of library resources, services and physical environment. This is done by investigating the following:

1. Users’ satisfaction with library services,

2. Users’ satisfaction with library resources

3. Users’ satisfaction with staff conduct.

4. Contribution of the library to the academics of users

The motivation for this study is to demonstrate the value of the library in order to justify funding for resources, as well as identify users’ needs towards better service provision. Putting this study into perspective, some existing literatures have been reviewed.

Demonstrating the value of academic library

Throughout history, academic libraries have served their institutions as repository, information provider, recreational facility, computer and information literacy training provider, and advocator among others. These services evolved as a result of changing needs of users and community. In spite of these achievements, libraries are said to be struggling with expressing and quantifying their value to stakeholders (Jaeger et al., 2011).

Tenopir (2011), discussing ways of measuring the value of library products and services mentioned:

1. The implicit value where focus is put on downloads or usage logs. This approach assumes that because the library is used, it has value. This however does not show purpose, satisfaction or outcome.

2. Explicit value focuses on the impact or the outcome on research, teaching and learning,

3. Derived value deals with the cost benefits of library resources. This is also referred to as Return on Investment (ROI).

According to Tenopir (2011), Tenopir et al. (2009b)and Tenopir et al. (2009a), most libraries have demonstrated implicit value for some time using usage statistics. For instance, Tenopir (2011)stated that usage logs revealed increase in downloads of e-resources over the last decade. Besides, a reading survey showed that reading among academics increased steadily from 150 articles in 1977 to about 280 by 2006 over the past. Implicit value assessment however does not demonstrate purpose, satisfaction or outcome of use, hence Tenopir (2011)advocated that the value of library should not only focus on implicit value where focus is put on downloads or usage logs but also on the explicit and derived values where impact on research, teaching and learning, and the cost benefits of library resources are assessed.

Some researches built upon this approach by not just collecting frequency of use but also assessing the purpose, motivations and outcomes. In a study of seven universities in the USA and Australia in 2004 to 2006, it was discovered that half of the scholarly article readings were for research purpose. Furthermore, Cobblah and Van Der Walt (2016), Dunne et al. (2013)and Botha et al. (2009)demonstrated explicit value of libraries by assessing user satisfaction of library services, resources and expertise. A survey conducted by the School of Library and Information Science at the University of South Carolina reported that 92% of users think that library improves the overall quality of life and 73% feels that the library enhances personal fulfilment (Jaeger et al., 2011). Similarly, Sriram and Rajev (2014)and Poll (2012)posited that impact and outcome is required to establish value. Moreover, Chandrashakara and Adithya (2013), Arinawati (2011)and Harvey (2004)demonstrated library value by assessing the acquisition process of library materials, use of budget and maintenance of stock.

The popularity of the explicit value approach was due to the development of some methods and standards of assessing library services and resources. Markless and Streatfield (2006)identified four criteria for measuring users’ satisfaction with library resources:

1. Attitudinal change or change of perception

2. Knowledge about sources of relevant information.

3. Behavioural change – doing things differently

4. Doing things more effectively.

Furthermore, the SCONUL Impact Initiative also proposed stages in assessing the impact of higher education libraries (Payne, 2006). Also, library collaborations have developed toolkits, methods and procedures such as the ACRL Standards 2011, LQAF (Library Quality Assessment Framework) for NHS libraries in England, the new international standard, and the ISO 16439 to provide clarity and consistency to library assessments (Hiller, 2013; Poll, 2013, 2012; Dunne et al., 2013). Moreover, Weightman et al. (2009)and Abels et al. (2002)made separate contributions on measuring the impact of health libraries.

Despite the above measures, Dunne et al. (2013)asserted that measuring satisfaction is problematic because:

1. LIS impact studies tend to rely on users subjective views.

2. It is difficult to isolate cause and effect as they apply to use of service and subsequent change.

This notwithstanding, LIS impact study can still be useful as long as researchers accept their limitations, reduce bias and make the study relevant to learn from Urquhart (2004).

In recent times, policy makers and business minded stakeholders especially sponsors require library value measurement based on fiscal benefits of resources. In response to this, libraries especially public libraries adopted the Return on Investment (ROI) approach to demonstrating value, which associates library services with costs or potential prices. Libraries in Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Florida and South Carolina have used the ROI model (Jaeger et al., 2011). Also, Sykes (2003)asserted that “library value is often seen through the lens of a business model particularly a Return on Investment perspective”. The approach involves the use of ‘value calculators’ which quantifies library value into the amount of money saved when a user borrows from the library rather than paying for the material. The problem with these concepts is that, the accuracy of services listed and corresponding prices quoted cannot be established. The risk associated with this therefore is that, ‘the services could appear too expensive or simply cost-inefficient’ thus ‘creating negative reactions’ (Germano, 2011). Jaeger et al. (2011)also argued that since libraries are social institutions, translating their services and products into monetary terms becomes unsuccessful. Explaining further, the research stated that information, knowledge and data do not have monetary value unless they are used to create a commodity then perhaps monetary figure can be imposed.

Another way by which library (especially public library) value has been demonstrated was by looking at library usage during times of economic crisis such as the Great Depression and the decade old economic crunch. Jaeger et al. (2011)citing Griffiths and King (2011); Carlton (2009); Yates (2009), Gwinn (2009), Jackson (2009), and van Sant (2009) reported that in the USA during the economic crunch, library usage increased significantly as patrons sought internet access, assistance to apply for jobs, social services and options for entertainment among others. Statistics collected shown that there was 5% increase in library cards issues, 10% increase in library visits and 17% increase in visits to library websites. In the studies, internet service revealed great potential to measure and express the economic value of public libraries by enabling assistance in education, technological literacy, job seeking, applications for social services, and other measurable contributions to the economy. About 3.7 million people have been reported to have successfully obtained employment through the use of library computer service (Jaeger et al., 2011).

In view of the limitation with measuring library satisfaction, Tanner (2012)suggested both the economic value and the social value approaches for demonstrating library value. It is also necessary for libraries to share assessment data with stakeholders to facilitate funding. Consequently, libraries should demonstrate value by establishing the intrinsic worth of their services based on patrons’ needs. This can be done by assessing the need of users and understanding the industry in which libraries operate so as to offer more attractive options for potential users who patronise other information providers.

User satisfaction as an indicator of library value

According to Hernon and Altman (2010), “satisfaction is an emotional reaction, the degree of contentment or discontentment with a specific transaction or service encounter”. If the service performance falls below users’ expectations, they become dissatisfied. However, if service performance matches expectations, users become satisfied (Bua and Yawe, 2014). Therefore, satisfaction can be personal and it is the degree at which users are pleased with the library services, with staff attitudes, and the library environment in fulfilling their needs and expectations. Giese and Cote (2000)explained that a user’s respond while a service is being delivered or after service delivery is indicative of user satisfaction. It can therefore be inferred that satisfaction is an individual response to a service and it can be subjective depending on the time and needs of a user. It may or may not directly relate to the performance of the library. In service organisations, satisfaction plays a major role, and according to Alasandi and Bankapur (2014), it is the positive feeling created after receiving a service that makes users desire to use the service again. In view of this, all libraries strive to satisfy the information needs and expectations of users (Warraich and Ameen, 2011). According to Bua and Yawe (2014), the extent to which an academic library services satisfy its users defines how effective or efficient that library is. For the purpose of this study, user satisfaction shall mean the fulfilment of users’ (students and faculty staff) expectations and needs as they use the library services and resources for learning, teaching, research and other purposes.

Academic libraries provide services and information resources ranging from print publications, e-resources, conducive environment, book lending, reference services, catalogue, photocopying, printing, study desks, computer and ICT facilities, information retrieval and delivery services, user information alert, interlibrary loan, research support, publishing support, technical support, information literacy, advocacy and policy formulation functions among others. These have been identified as key determinants of service quality in the libraries. Sriram and Rajev (2014)cited Abagai (1993) who also ascertained that the availability of the skilled staff, knowledge materials and physical environment can guarantee user satisfaction. Onuoha (2010)also assessed library services at Babcock University in Nigeria, and the findings revealed that circulation service, reference, photocopy and binding services were considered by the majority of the respondents to be effective, while compilation of bibliographies, indexing and interlibrary loan services were considered to be ineffective. Biradar et al. (2009)and Martin (2003)investigated the quality of library services and their findings revealed that the users were generally satisfied with library services but had specific concerns with areas such as access to electronic resources, catalogues and insufficient space.

Also, in a study conducted by Mohindra and Kumar (2015)to assess library service quality (LSQ) base on user satisfaction of AC Joshi Library, Panjab University in Chandigarh, India, found that library environment and library services outscored library collections in predicting user satisfaction. The findings of another study on a Malaysian University also revealed that (i) academic staff perceive the quality of library services to be just above average, (ii) library staff are considered quite helpful and able to instil confidence in library users, (iii) academic staff also believe that the library has a positive impact on their teaching, learning and research, and (iv) the overall satisfaction with the library services received a satisfactory rating (Kiran, 2010). Besides, Heider et al. (2012)recorded that studies have shown that library materials contribute to faculty’s publications as a result, faculty’s comment on their evaluation of resources and services was that libraries should expand access to e-resources and e-services. Other researches on the value of libraries based their assessment on the relevance of libraries’ collections – both print and electronic (Heider et al., 2012).

Furthermore, printing and photocopying facilities were found to have significant impact on user satisfaction in the Sur University College Library, Sultanate of Oman (Sriram and Rajev, 2014). Also, Cobblah and Van Der Walt (2016)investigated the contribution of effective library and information services to academic achievements at universities in Ghana and concluded that there was a correlation between effective library and information services, and academic achievements at the universities in Ghana. The study also established that library users were generally satisfied with the services provided. The provision of study space, book lending and internet services were the most effective and highly patronised services. The study also indicated that inadequate staff training programmes affected the ability of library staff to deliver effective library services.

These literatures have established that library collections, services and facilities include space, are key to user satisfaction. As stated earlier, user satisfaction is a personal response which can be determined by the needs and expectations of the user, hence even though some found satisfaction in library collections, others were impressed with services and yet others were pleased with library facilities such as computer, internet and space. It can also be realised that while earlier researches employed user satisfaction to determine implicit value of libraries, later publications established the explicit value of libraries which focuses on the impact of library services and products, to establish user satisfaction.

Effects of library use on student’s academic achievement

Academic libraries are essential in providing information resources and services to support teaching, learning and research. Vichea et al. (2017)supported this statement with the assertion that information is very important in order to achieve academic success. In view of this, many researches have established a strong correlation between library use and students performance. Investigating library use at Huddersfield University, West Yorkshire, Goodall and Pattern (2011)acknowledged that students who read more; as measured in terms of borrowing books and accessing electronic resources attain better grades. In addition, Cox and Jantti (2012)and Wells (1995)assessed the impact of library use at the University of Wollongong, New South Wales and the University of Western Sydney, Macarthur respectively and established that there was strong correlation between students’ grades and use of library information resource. This is supported by a study done to evaluate the impact of library on students’ retention and performance in the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. The findings of the study suggested that “first-time, first-year undergraduate students who used the library had higher GPA for their first semester and higher retention from fall to spring than non-library users (Soria et al., 2017).

In another study however, the relationship between academic performance of students and library use could only be established partially (De Jager, 1997). This raised the question as to whether books borrowed from library were always read or understood by students. This notwithstanding, majority opinion still established that library use positively impacts students’ academic success. It has also been established that, “undergraduates attending research universities with greater academic library resources had higher self-reported gains in critical thinking” (Whitmire, 2002). Moreover, Atta-Obeng (2016)citing Amusan et al. (2012), Wijetunge (2000), Haggstrom (2004), Igbinovia (2016) and Eve et al. (2007) ascertained the contributions of academic libraries in promoting lifelong learning skills such as information literacy skills, research publishing, communication, presentation skills, ICT skills, and students’ ability to collaborate and share knowledge. Through this, libraries would be able to resolve the demand for accountability for students’ achievements. In essence, libraries should not only focus on usage and download counts as well as users impressions to determine library value. The trends are changing where libraries are being required to also establish value through impact. In this study, user satisfaction has been used to establish both the implicit and explicit values of libraries.

The study is a survey of two university libraries namely, the Ghana Institute of Journalism (GIJ) Library, and Todd and Ruth Warren Library, Ashesi University College (AUC), Ghana. The researchers used questionnaires and interviews to collect qualitative data from third year students, faculty and library staff on their perceptions of the libraries’ resources and services. Faculty and library staff were interviewed while third year students were given questionnaires consisting of open and close-ended questions to complete. The reasons for choosing third year students are because most of them were continuing students who had the opportunity to use the library for a long period. Also, from observation, unlike final year students who due to the intensity of their academic work are not willing to participate in other activities, third year students are more available and willing.

Four hundred and ninety-six (496) third year continuing students were proportionally sampled from a total student population of 2,216 from both universities. This constitutes 349 out of 1,697 students from GIJ and 147 out of 619 students from Ashesi University College (AUC). Since not all the 349 GIJ students were continuing students, purposive sampling was used to further select the 185 continuing students out of a total of 349 third year students. To enhance the response rate and also to have different opinions of the quality and value of the library’s services, 30 out of 45 faculty staff were sampled from both institutions base on their availability at the time of data collection. This constitutes 15 out of 26 faculty staff from GIJ and 15 out of 19 faculty staff from AUC. Eight (8) out of 10 professional and para-professional library staff were also sampled purposively for interview. This constitutes 5 out of 6 GIJ library staff and 3 out of 4 AUC library staff. In all, data was collected from a total of 370 respondents sampled out of a population of 2,271 students, faculty and library staff.

The response rate for the questionnaires was 73% (135) for GIJ and 83% (120) for AUC while that of faculty and library staff was 100% for each of the institutions.

The researchers used both open-ended and close-ended questions. The close-ended question comprises both multiple options and rank scaled questions. The questionnaires for GIJ differ slightly from that of AUC in that, questions on e-resources and reprographic services are excluded because the library did not offer those services.

The questionnaire constitutes questions on (a) requested background data of respondents, (b) availability and evidence of usage of services and purposes for which the services are used, (c) the awareness of the various services provided by the libraries, (d) users’ perceptions of service quality, and (e) perceptions of the value of using the library services.

Some of the questions were adopted from the data collection instruments employed by McCreadie (2013)in her investigation into library value in selected developing countries. McCreadie‘s study used instruments such as quantitative questions for both library staff and faculty, qualitative telephone interviews with selected librarians and qualitative open-ended questions which were e-mailed to faculty staff. The purposes for adapting these questions for the present study were that they are appropriate for the investigation. Examples of questions adopted from McCreadie are: On a scale of 1 to 10 how do you value your library? Which of the services provided by your library is of most value to you? What do you value most about the services of your library?

The questionnaires were self-administered at the libraries and lecture halls of both institutions because the respondents were within reach.

Unstructured interviews were conducted in the offices of the respondents (faculty and library staff) by the researcher after booking appointments with the lecturers and library staff. The interviews were recorded and later transcribed.

SPSS 21.0 was used to organize and analyse the data. Data was analysed using the descriptive and frequency distribution methods of data analysis. Findings were illustrated using tables and graphs.

Users’ satisfaction with library services

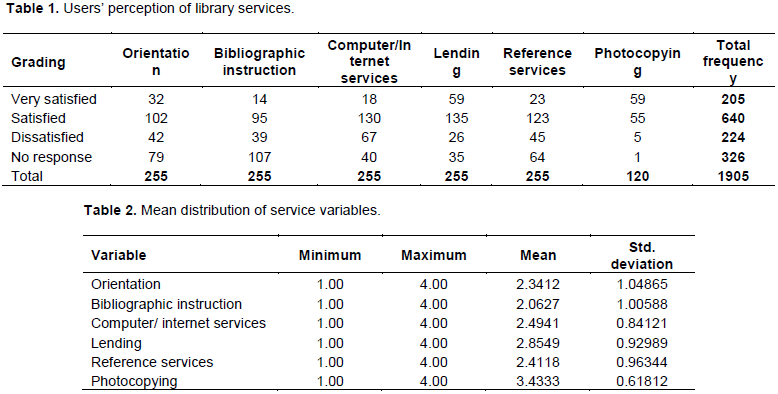

According to Albert (2014), libraries are able to demonstrate value when they collect data to assess library usage and impart. Also, according to Cobblah and Van Der Walt (2016), academic libraries need to critically examine the effectiveness of their services in order to judge their performance. In view of this, students, faculty and library staff of the GIJ and AUC were asked to value the quality of services offered in their libraries. The results are displayed in Tables 1 and 2.

It can be realised from Table 1 that photocopying services has less responses (120). This is because only one institution offered photocopying services. With a scale rating of 1 - 4 where 1 = ‘no response’, 2 = ‘dissatisfied’, 3 = ‘satisfied’ and 4 = ‘very satisfied’, the mean distribution of the variables for library services are captured in Table 2. As shown, orientation service records a mean of 2.3412, bibliographic records 2.0627, computer/internet services records 2.4941, lending service records 2.8549, reference services records 2.4118 and photocopying records 3.4333.

Comparing the means, it is obvious from the analysis that photocopy service has the highest level of satisfaction (m = 3.4333). The next level of satisfaction is scored by lending service (m = 2.8549). Comparatively, users derive the least level of satisfaction for bibliographic instruction service (m = 2.0627). In view of this, measures have to be taken to enhance bibliographic instruction. That notwithstanding, the mean of 2.0627 is moderate since it is within the middle of the scale (1-4). It can therefore be posited that, the general overview of users’ perception of library services is satisfactory.

The findings support the research of Sriram and Rajev (2014) that printing and photocopying facilities have significant impact on user satisfaction in the Sur University College Library, Sultanate of Oman. Cobblah and Van Der Walt (2016)also confirms this by asserting that “…library users were generally satisfied with the services provided by the university libraries”.

Again, the findings confirmed results from a survey conducted in 2012 about users’ expectations of the GIJ library. In that study, students were more satisfied with the services than with the physical library and their access to information (Nyantakyi-Baah and Afachao, 2012).

In spite of the generally high satisfaction for service, the study recorded some dissatisfaction. Figure 1 reveals the general perception of users on library services.

A total of 34% of users gave no response or were dissatisfied with library services offered. The reason for not responding could probably be due to lack of awareness of the existence of the services, which equally shows poor service. Reasons for users’ dissatisfaction are revealed by responses from the interview where users complained that:

1. The libraries have few computers,

2. Slow internet,

3. No information literacy training for users and

4. Poor assistance for students’ projects.

This therefore requires necessary action to increase the computer systems and the broadband. Also, more library staff should be employed and trained to offer information literacy training and better assistance for students’ projects.

Satisfaction with staff conduct

With respect to staff conduct, a total of 86% of the respondents indicated satisfaction (Figure 2). The above perception was supported by a positive response from faculty staff. They were pleased with staff conduct and hard work irrespective of the challenges staff faced. Some lecturers commented as follows:

I have been contacting the library to teach my English class on how to use library and the Internet for searching for information.

I haven’t met all the library staff but the ones who have served me, I will say their conduct was very satisfactory and I am very satisfied.

I am very satisfied because the staffs are doing a good job, they are helpful.

I am satisfied because they keep updating us on new resources all the time.

Reasons for their satisfaction were that they offered instructional services, and library staff was dynamic, very helpful, update faculty on available materials, and they made it easier for faculty to access information.

These responses were confirmed by an annual satisfaction survey and feedback undertaken at the AUC. However, two of the library staff stressed that their users were satisfied but not completely satisfied, because of some challenges. In confirmation, library staff member remarked that:

They are satisfied but I wouldn’t say they are 100% because there are certain things that they are looking for which we are not able to provide, but they are okay.

Library staff from GIJ confirmed that users are satisfied with the services because they receive fewer complaints now from students.

This finding confirms the assertion of Hernon and Altman (2010)that the attitude of library staff when delivering service affects user satisfaction. It is clear that satisfaction with service was regarded as synonymous with how service providers conduct themselves in the process of service delivery.

On the other hand, 14% minority as shown in Figure 2 expressed dissatisfaction. This is probably due to complaint that staff do not interact with faculty to know their information needs. Also interview responses from faculty and library staff revealed that the number of library staff is too small and some library staff show bad attitude towards users. In response to poor attitude of staff, customer relation trainings have been undertaken with the hope of improving staff conduct. In effect the institutions surveyed would have to hire more library staff and train them to build the needed capacity to serve. This supports Cobblah and Van Der Walt (2016)’s claim that inadequate staff training affects library staff’s ability to deliver efficient service. The libraries should collaborate with faculty by introducing liaison librarianship service in the institutions.

Satisfaction with information resources

As indicated by Saikia and Gohain (2013), the collection of a library plays a major role in determining the effectiveness of the library. Therefore, the collection should be selected in a way that will meet the expectations of users and satisfy their information needs. Adeniran (2011)had also emphasised that meeting the information needs of library users demanded the provision of actual information resources that satisfy users. When students were asked to appraise the relevance of books, magazines, journals, online information resources, newspapers and other information resources in their libraries, Figure 3 shows that 80% majority respondents were satisfied with the information resources while 20% were dissatisfied.

In GIJ, staffs were divided on their opinion about information resources. Some faculty staff were satisfied with the information resources in the library, because they perceived the materials available to be relevant and meeting their information needs. The Dean of Communications and Social Science, who was one of the interviewees shared his view:

I have noticed that you have relevant books in my field of studies, communication studies and I am also conscious of the fact that you are always sending us list of new additions, so for me I think I am satisfied.

On the other hand, others were not satisfied and they were of the opinion that the library is not sufficiently well resourced. For instance, they mentioned that the library does not have e-books and e-journals and some of the materials were out-dated. These were the same reasons they gave for not considering the library materials as of high quality. A comment from a faculty staff who was dissatisfied was:

No, I am not satisfied because there are no journals, e-books and e-journals and some of the books are old, a lot more room for improvement.

Fortunately, this complaint of lack of e-journals and e-books have been resolved since the GIJ library has recently joined the Consortium of Academic and Research Libraries in Ghana (CARLIGH) and now have access to extensive electronic information resources.

Again, response from library staff confirms users’ dissatisfaction with information resources. Reason given being; most books on the open shelf areas were old. A comment from a library staff member was:

Users are generally satisfied with the reference materials but they express dissatisfaction with the materials on the open shelves though access to reference textbooks is restricted.

With regard to the AUC Library, interview responses from faculty and library staff indicated that the information resources were commendable. Only one faculty member complained that he was not satisfied with some of the magazines because they were not current. However, the rest were very impressed especially with the electronic resources. A faculty member made this comment:

I am satisfied because the electronic resources are relevant.

The library staff confirmed users’ satisfaction with a special mention of the textbook policy which enables individual student to have access to textbooks and to keep them till the end of a semester.

Both positive and negative responses revealed the importance of providing adequate and relevant information resources for libraries. This supports the argument that libraries are still relevant in spite of alternative sources of information.

Satisfaction with library environment

The library environment and physical facilities play a major role in providing quality and a satisfactory service to users. The building should be purposely built to facilitate the maximum use of all the resources in the library. Abbasi et al. (2014)recommended that the library should be situated in an appealing and attractive environment; it should have appropriate lighting systems because it creates a conducive atmosphere for learning. The fittings should be comfortable and attractive in appearance with enough balance between informal and study type seating.

When students were asked to evaluate the physical library building with its facilities, Figure 4 revealed that a total of 79% of respondents indicated that they were satisfied while (21%) thought that the library environment does not meet their expectation as far as a place of learning and conducting research is concerned. At AUC, reasons given for the dissatisfaction were noisy at night, crowding at certain times, and inadequate air condition.

All faculty staff interviewed responded that they were satisfied with the library environment due to its unique architectural design and the interior arrangement. A lecturer commented:

I am satisfied because it is a welcoming place and the building is so distinctive.

Surprisingly in GIJ, even though majority of students were generally satisfied with the library environment, faculty and library staff was however not satisfied with the library environment. Perhaps students were considering the well organised nature of the library, besides, they might not have been exposed to other libraries unlike the lecturers who might have had the opportunity to use bigger and well stocked libraries.

The perception of faculty was that the library environment was of poor quality because the library space is inadequate. Therefore, it is not a surprise that they were dissatisfied. Some comments from faculty:

That is where I have a problem, I think the library in terms of space is very small and it is a challenge for me as a lecturer.

I haven’t seen any significant change but I think it will also be disingenuous on my part to say there hasn’t been improvement, especially the arrangement in the library is orderly and bit more user friendly than when I was a student- a lecturer and an old student.

The responses from the library staff support the responses of the faculty staff about their dissatisfaction with the library environment. All library staff interviewed stated that the library space is too small; creating congestion during peak time. This finding therefore demands action to enhance the GIJ Library space.

Usefulness of the library to users

In assessing the contribution of library services to the academics of users, respondents were asked to give the kind of help received from the library and what that help enabled them to achieve. On a whole, 95.2% respondents have received various assistances from the libraries while only 4.8% had never received any help from the library as shown in Table 3. In one of the libraries, students received most help, with locating books or relevant materials (24.5% responses) and assistance in doing assignments and project work (14% responses). Other help received were in the form of orientation, or searching for information using the Internet. The assistance given to users was really considered beneficial and they appreciated it. The following are comments from students:

I was doing a project on the use of library by students of GIJ and the head of the library gave me all the assistance I needed. I was able to get the necessary information and it earned me good grade in that particular course. I needed reference books to write my assignment for end

of semester project and the library staff helped me found one, I had a high mark that I think I couldn‘t have gotten without the library.

This notwithstanding, the response from 4.8% that they have never received help from the library need to be addressed. This response could either be due to complained such as overcrowding, noise, poor staff attitude, and lack of irrelevant and inadequate resources of the respondents do not know the relevance of library to them. In either case, it is necessary that these complaints be addressed. Besides, library services and resources should be publicised. Also, off campus services should be introduced through online portals, so that all students can benefit from library services.

The respondents as displayed in Table 4 enumerated how the help they received from the library has impacted positively on their academic work. Sixty-four (23.8%) indicated that the use of the library enabled them to submit their assignments on time. Forty-two (15.6%) mentioned that the assistance from the library enabled them to understand their subjects. Another significant benefit that is worth noting is that ten (3.7%) of the respondents achieved a good grade in their exams. This confirms the claim by Soria et al.(2017)and Cox and Jantti (2012)that students who use the library frequently get higher GPA.

The other benefits such as the ability to search for the appropriate information online, ability to do project work, ability to acquire presentation skills and the ability to print and photocopy own work were also mentioned. Some of these skills mentioned have been confirmed by Atta-Obeng (2016)that academic libraries have enabled students to acquire lifelong learning skills like presentation and information literacy skills among others. Below is a comment from a student:

One of the staff helped me search for information for my assignment and actually taught me how to cite all the references. In fact I couldn‘t have done it without him.

The faculty staff also confirmed that the library had been helpful to them in their last research or project. Every faculty member interviewed had received help from the library especially in the area of facilitating access to relevant documents for various purposes. Here is a statement made by a faculty staff member:

I had a document from the library on election campaign and that is exactly what I am doing so my contact with the library goes a long way to enrich my thesis.

Yes, they gave me a book and it was on Aristotle‘s view on colours that informed the writing of an article on branding that I needed to do and how colour can be used as part of branding, it was insightful, and it gave me another perspective of colour and branding.

In addition, there were seven responses that indicated other support the library had offered to faculty staff. Such support had been in the form of accessing relevant materials that enabled them to prepare and teach new courses and being informed in their research interest area. A comment from a faculty staff:

The head librarian helped me to identify appropriate resources and it enabled me to have the idea of what other people are doing in my research interest area.

The library staff were asked whether the use of the library by the third year students had any positive influence on them for example, acquiring skills in searching for information and what evidence they had for that. The library staff said yes it had indeed been helpful to students. However, the head librarian was of the opinion that the impact is personal as it varies from a user to user depending how frequently individuals had used the library since their first years.

I think it is personal, but those that have been coming to the library since first year now don’t depend on us so much to search for information, some can now search and use information properly, but for those who do not patronise the library services, I don’t think they have had much impact.

Library staffs were also asked if they thought that the use of the library by the third year students had any positive influence on the students. They all responded in the affirmative, that the use of the library enabled the students to acquire lifelong skills like searching for information through the one-on-one assistance they offer to users. They mentioned that through observation they realised that the dependence of the third year students on staff for assistance has actually reduced over time. A comment from a library staff member was:

Yes, students are positively influenced unlike most of the first and second year students, third year students don‘t depend much on staff of the library when searching for information or conducting research.

I think it is personal, but those that have been coming to the library since first year now don‘t depend on us so much to search for information, some can now search and use information properly, but for those who do not patronise the library services, I don‘t think they have had much impact.

The above comments from faculty and the services providers are indications that the library has helped students and faculty, especially in accessing information, and the help has influenced them positively.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The survey has ascertained that academic libraries are of high value to both students and faculty. Library services, resources, physical environment and staff conduct all recorded high satisfaction. Among the services, book lending and photocopy services recorded highest levels of satisfaction. The study also revealed that through the library students have been able to obtain some lifelong learning skills such as presentation skills, ability to use internet, and the ability to find information materials in a library. Again, it was recorded that through the library some students got good grades. Moreover, 80% majority of respondents were satisfied with library information resources. This supports the argument that libraries are still relevant in spite of alternative sources of information. This confirms the impact of libraries as mentioned by Cobblah and Van Der Walt (2016). Furthermore, 79% majority of respondents showed satisfaction for the library environment. However, a total of 34% of respondents showed dissatisfaction with library services, 20% showed dissatisfaction with information resources and 21% showed dissatisfaction with library environment. Even though these are minority, their responses raise concerns for necessary measures to be taken. It is therefore recommended that the libraries should be equipped with relevant and adequate information resources. In respect to this, online resources are critical. In addition, the number of computers as well as the size of broadband should be increased to address challenges with online service delivery. Moreover, the number of library staff should be increased and continuous professional development provided to build their capacity to serve. This can improve staff conduct and facilitate collaboration between the library and stakeholders especially faculty. Furthermore, it is recommended that the library space be expanded and adequate air conditions provided to make the place comfortable and less noisy. Finally, marketing of library services and resources is highly recommended to create awareness, educate users and demonstrate value.

In conclusion, it should be reiterated that for the academic library to be perceived as valuable by its community, it should reflect the academic society that it serves and should be made approachable to all users in the community who need the library to satisfy their information needs. The library should make sure it is deeply embedded in the university community by contributing to the teaching, learning, research and other activities through provision of relevant and accessible information services. By so doing, libraries will be able to meet the expectations of their stakeholders, demonstrate value to justify funding as well as establish their relevance over alternative sources of information.

The following are areas of further research necessary to compliment this study:

1. Users’ satisfaction with online services, staff ICT competence, advocacy and policy formulation functions of the library.

2. Library value from the perspective of university management.

The assessment of value was limited to users’ opinion. The perception of the universities’ management was not considered.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Abagai T (1993). The use of library in a non-residential college: A case study of Kaduna State college of education. Forum Academia: Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research 1(1):104.

|

|

|

|

Abbasi N, Tucker R, Fisher K, Gerrity R (2014). Library spaces designed with students in mind: an evaluation study of University of Queensland Libraries at St Lucia Campus. Proceedings of the 35th IATUL Conferences on Measures for Success: Library Resources and Effectiveness under Scrutiny. Retrieved from View

|

|

|

|

|

Abels EG, Cogdill KW, Zach L (2002). The contributions of library and information services to hospitals and academic health sciences centers: a preliminary taxonomy. Journal of the Medical Library Association 90(3):276-284. Retrieved from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Adeniran P (2011). User satisfaction with academic libraries services: academic staff and students perspectives. International Journal of Library and Information Science 3(10):209-2016.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Alasandi BB, Bankapur V (2014). Library satisfaction survey of the students and faculty members of Bharatesh's Global Business School, Belgaum, Karnataka: a user study. International Journal of Information Dissemination and Technology 4(2):163-167.

|

|

|

|

|

Albert AB (2014). Communicating Library Value: the missing piece of the assessment Puzzle. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 40:634-637.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Amusan DA, Oyetola SO, Ogunmodede TA (2012). Influence of Library and Information Services on Attainment of Millennium Development Goals on Education : A Case Study of Oyo State, Nigeria. AMERICAN International Journal of Contemporary Research 2(8):213-222. Retrieved from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Arinawati A (2011). An Assessment of the Effectiveness of Library Resources and Services in Supporting Researchers' Information Needs. Seminar Kebangsaan Perpustakaan Akademik. Pulau Pinang: Universiti Sains Malaysia.

|

|

|

|

|

Asamoah-Hassan H (2014). The Consortium of Academic and Research Libraries in Ghana - the Journey so Far,. Accra, Ghana.

|

|

|

|

|

Atta-Obeng L (2016). Promoting knowledge and skills for lifelong learning. The University of Ghana, Accra, Ghana.

|

|

|

|

|

Biradar BS, Kumar PD, Mahesh Y (2009). Use of information sources and services in the library of Agricultural Science College, Shimoga: A case study. Annals of Library and Information Studies 56:63-68.

|

|

|

|

|

Botha E, Erasmus R, Van Deventer M (2009). Evaluating the impact of a Special Library and Information Service. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science 41:108-123.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bua FT, Yawe AA (2014). A comparative study on user satisfaction with the management of library services in three academic libraries in Benue State-Nigeria. Journal of Studies in Social Sciences 6(1):23-30. Retrieved from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Carlton J (2009). Folks are flocking to the library, a cozy place to look for a job: Books, computers and wi-fi are free, but staffs are stressed by crowds, cutbacks. Wall Street Journal (15 January), p. A1.

|

|

|

|

|

Chandrashakara JH, Adithya (2013). Measuring Library Effectiveness in VTU Research Centres in Karnataka: A Study. Library Philosophy and Practice. p. 1.

|

|

|

|

|

Cobblah MA, Van Der Walt T (2016). The Contribution of Effective Library and Information Services to Academic Achievements at Some Selected Universities in Ghana. Libri 66(4):275-289.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cox BL, Jantti MH (2012). Discovering the impact of library use and student performance. Educause Review (July 18):1-9.

|

|

|

|

|

Creaser C, Spezi V (2012). Working together: the evolving value of academic libraries. Retrieved from

View

|

|

|

|

|

De Jager K (1997). Library use and academic achievement Value of student library use. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science 65(1):26-30.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dunne M, Nelson M, Dillon L, Galvin B (2013). Library value and impact: Taking the step from knowing it to showing it. Library and Information Research 37(116):41-61.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Eve J, de Groot M, Schmidt A (2007). "Supporting lifelong learning in public libraries across Europe", Library Review 56(5):393-406.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Germano M (2011). The library value deficit. Bottom Line 24(2):100-106.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Giese J, Cote J (2000). Defining consumer satisfaction. Academy of Marketing Science Review 1(1):1-26.

|

|

|

|

|

Goodall D, Pattern D (2011). Academic library non/low use and undergraduate student achievement. Library Management 32(3):159-170.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Griffiths JM, King DW (2011). Public libraries are particularly essential in recessions. Providence Journal (27 July), at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Gwinn MA (2009). Library use jumps in Seattle area; Economy likely reason. Seattle Times (23 January), at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Haggstrom BM (2004).The role of libraries in lifelong learning. Available at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Harvey L (2004). Analytic Quality Glossary. Quality Research International.

|

|

|

|

|

Heider K, Janicki S, Janosko J, Knupp B, Rahkonen C (2012). Faculty Perceptions of the Value of Academic Libraries: A Mixed Method Study. Library Philosophy and Practice (e-Journal) 909. Retrieved from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Hernon P, Altman E (2010). Assessing service quality: satisfying the expectations of library customers (2nd ed.). Chicago, Illinois: American Library Association.

|

|

|

|

|

Hiller S (2013). Standards and academic libraries. The 10th Northumbria International Conference on Performance Measurement in Libraries and Information Services. Pp. 22-25.

|

|

|

Hinchliffe LJ (2011). Understanding, demonstrating and communicating value: the leadership and management challenge. Conference Paper Submitted to the World Library and Information Congress: 77th IFLA General Conference and Assembly. pp.13-18. Retrieved from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Igbinovia M (2016). "Libraries as vehicle to sustainable developmental goals (SDGs): Nigerian's current status and outlook". Library Hi Tech News 33(5):16-17, available at:

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jackson DZ (2009). The library - A recession sanctuary. Boston Globe (3 January), at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Jaeger PT, Bertot JC, Kodama CM, Katz SM, DeCoster EJ (2011). Describing and Measuring the Value of Public Libraries: The growth of the Internet and the evolution of library value. First Monday 16(11).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kiran K (2010). Service quality and customer satisfaction in academic libraries. Library Review 59(4):261-273. https://doi.org/10.1108/00242531011038578

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Markless S, Streatfield D (2006). Evaluating the impact of your library. London: Facet Publishing.

|

|

|

|

|

Martin S (2003). Using SERVQUAL in health libraries across Somerset,

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Devon and Cornwall. Health Information and Library Journal. Retrieved from

View

|

|

|

|

|

McCreadie N (2013). Library value in the developing world. IFLA Journal 39(4):327-343.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mohindra R, Kumar A (2015). User satisfaction regarding quality of library services of A.C. Joshi Library, Panjab University, Chandigarh. DESIDOC Journal of Library and Information Technology 35(1):54-60.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nyantakyi-Baah L, Afachao E (2012). Reality versus desire: the case of GIJ library users' expectations. Proceedings of the 8th Seminar of Committee of University Librarians and Their Deputies (CULD) on Academic and Research Librarian in the 21st Century. Cape Coast, Ghana: University of Cape Cost.

|

|

|

|

|

Onuoha UD (2010). Faculty assessment of, and satisfaction with, library services in Babcock University, Nigeria. Contemporary Humanities 4(1/2):287-297.

|

|

|

|

|

Payne P (2006). The LIRG/SCONUL impact initiative: assessing the impact of HE libraries on learning, teaching, and research,. Library and Information Research 30(96):2-12. Retrieved from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Poll R (2012). Can we quantify the library"s influence? Creating an ISO standard for impact assessment. Performance Measurement and Metrics 13(2):121-130.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Poll R (2013). Library standards: how using them can demonstrate value and impact. The 10th Northumbria International Conference on Performance Measurement in Libraries and Information Services. Retrieved from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Ribble H (2011). Why libraries are relevant in the digital age. Digital Commons 32(2):64. Retrieved from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Saikia M, Gohain A (2013). Use and user's satisfaction in library resources and services: a study in Tezpur University (India). International Journal of Library and Information Science 5(6):161-175.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Soria KM, Fransen J, Nackerud S (2017). Library use and undergraduate students outcomes: New evidence for students' retention and academic success. Libraries and the Academy 13(2):147-164.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sriram B, Rajev MKG (2014). Impact of Academic Library Services on User Satisfaction: Case Study of Sur University College, Sultanate of Oman. DESIDOC Journal of Library and Information Technology 34(2):140-146.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Sykes J (2003). Value as calculation and value as contribution to the organization. Information Outlook 7(3):10-13.

|

|

|

|

|

Tanner S (2012). Measuring the impact of digital resources: the Balanced Value Impact Model. Retrieved from Kings College London website:

View

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tenopir C (2011). Beyond usage : measuring library outcomes and value. Library Management 33(1/2):5-13.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tenopir C, King DW, Edwards S (2009a). "Electronic journals and changes in scholarly article seeking and reading patterns." Aslib Proceedings: New Information Perspectives 61:1.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tenopir C, King DW, Spencer J, Wu L (2009b). Variations in article seeking and reading patterns of academics: What makes a difference? Library and Information Science Research 31(3).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Tetteh EOA (2018). Usage evaluation of electronic resources in academic and research libraries in Ghana. Global Knowledge, Memory and Communication 67(4/5):316-331.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Thomas S (2010). Introductory comments developing strong library budgets: information professionals share best practices. Library Connect Pamphlet 12:1-16. Retrieved from http://libraryconnect.elsevier.com/sites/default/files/lcp1201.pdf.

|

|

|

|

|

Tripathi M, Jeevan V (2013). A selective review of research on e-resource usage in academic libraries, Library Review 62(3):134-156.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Urquhart C (2004). Special topic: how do I measure the impact of my service? In A. Booth, A. and Brice (Ed.), Evidence based practice for information professionals: a handbook, London: Facet Publishing. pp. 210-222.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

van Sant W (2009). Librarians now add social work to their resumes. St. Petersburg Times (9 June), at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Vichea L, Nazy L, Sopanha M, Socheata V (2017). The Impact of Library Usage on UC Students ' Academic Performance 1:1. Retrieved from

View

|

|

|

|

|

Warraich NF, Ameen K (2011). LIS professionals' staffing patterns: Pakistani public sector universities. Library Philosophy and Practice 1.

|

|

|

|

|

Weightman A, Urquhart C, Spink S, Thomas R (2009). The value and impact of information provided through library services for patient care: developing guidance for best practice. Health Information and Libraries Journal 26:63-71.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wells J (1995). The influence of library usage on undergraduate academic success. Australian Academic and Research Libraries 26(2):121-128.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Whitmire E (2002). Academic library performance measures and undergraduates' library use and educational outcomes. Library and Information Science Research 24(2):107-128.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Wijetunge P (2000). The role of public libraries in the expansion of literacy and lifelong learning in Sri Lanka. New Library World 101(3):104-111.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Yates K (2009). Hard economic times: A boon for public libraries, CNN.com (28 February), at

View

|

|

|

|

|

Zhang X, Chen R (2008). Examining the mechanism of the value co-creation with customers. International Journal of Production Economics 116(2):242-250.

Crossref

|

|