ABSTRACT

The effect of strains on fertility, hatchability, and embryo mortality of indigenous chicken reared in the high rain forest zone of Nigeria was investigated. In this investigation, indigenous chicken with normal feathered phenotype, naked neck, and frizzle feathered phenotype which consisted of 10 cocks and 35 hens as the parents were used. They were put in 7 breeding groups: (1) Normal feathered cock with normal feathered hen (na × na ); (2) Naked neck cock with naked neck hens (Na × Na); (3) Frizzle feathered cock with frizzle feathered hens (Ff × Ff); (4) Frizzle feathered cocks with normal feathered hens (Ff × na); (5) Naked neck cock with normal feathered hens (Na × na); (6) Normal feathered cock with naked neck hens (na × Na), and (7) Normal feathered cock with frizzle feathered hens (na × Ff). The hens were five in each group and artificial insemination of the desired cock for each group was carried out twice a week before eggs were collected for incubation. Results from data analysis showed no significant difference (P>0.05) in fertility and embryo mortality within breeding groups. Egg fertility ranged from 58.82% for Na × na to 91.38% for Ff × na strain. Significant strain effect (P<0.05) was recorded for hatchability with highest value of 86.36% for na × na and the least value of 55.56% for Na × Ff strain. The Ff × Ff also had the highest embryo mortality of 34.36%. It was concluded that continuous reduction in the population of indigenous chicken with major gene of frizzling and naked neck may be attributed to greater loss of the chicks before hatching. There is need for adequate conservation of these rare genes in order to prevent them from going to extinction.

Key words: Hatchability, pure, crossbred chicken, normal feather, frizzle feather, naked neck, embryo mortality.

Indigenous chicken constitutes 80% of the 120 million poultry type raised in the rural areas in Nigeria (RIM, 1992). The growth rate of indigenous genotype chickens is generally much slower than that of commercial broilers (Pym et al., 2006). While broilers under typical confinement rearing may reach 2.0 kg live weight at five weeks of age, indigenous-breed male birds often weigh no more than 1.0kg at 20weeks (FAO,2010). This is a reflection of true genotype differences, but also of the rearing environment, in which feed quantity and quality is the major factor. Despite their lower productivity, in the village environment, the indigenous genotype birds have a number of advantages: they are self-reliant and hardy birds with the capacity for better resistance to diseases and parasites, ability to withstand harsh weather condition and adaptation to adverse environment. They are known to possess qualities such as the ability to hatch on their own, brood and scavenge for major parts of their food and possess appreciated immunity from endemic diseases (Ajayi, 2010). Their products are preferred by the majority of Nigerian because of the pigmentation, taste, leanness and suitability for special dishes (Horst, 1989). Their meat and eggs are also generally preferred to those from commercial birds, not only by rural communities but also often by urban dwellers (Pym et al., 2006). One of the important reasons to conserve local chicken genetic resources is to conserve the genetic variation within and between local breeds. Indigenous chicken also possess high genetic diversity for many traits and are therefore valuable genetic resources for present and future generations (Gueye, 2009; Dana et al., 2010). The future improvement and sustainability of local chicken production systems is dependent upon the availability of this genetic variation (Benítez, 2002). Fertility and hatchability are interrelated heritable traits and varies among breeds, varieties and individuals within a group. Fertility and hatchability parameters are most sensitive to environmental and genetic influences (Stromberg, 1975). There is a relationship between the number of spermatozoa inseminated and embryo survival (Eslick and McDaniel, 1992). They concluded that embryo mortality increased significantly with decreased number of inseminated spermatozoa. Under hatchability, there are many factors contributing to the failure of a fertile egg to hatch which include lethal genes, insufficient nutrients in the egg, and exposure to conditions that do not meet the needs of the developing embryo (Peters et al., 2008; King’ori, 2011). Fertility refers to the total number of incubated eggs that are fertile, while hatchability refers to set eggs that hatched. Limited information abound on the interactive effect of sire and dam of the Nigerian indigenous chicken, thus this study was designed to elucidate the fertility and hatchability of the indigenous strains in their pure and crossbred state.

The experiment was carried out at the Teaching and Research Farm, University of Port Harcourt, Port Harcourt (5.14’N and 6.44’E). The area lies in the South-South zone of Nigeria with a prevailing high average monthly rainfall ranging from 2400 to 3600 mm. The average temperature of the area ranged from 26 to 28.6°C during the rainy season and between 32 and 34°C during the dry season; although mild period occasionally prevailed. The relative humidity ranged from 70 to 90% and 4.8 to 6.5 h, respectively. Port Harcourt is situated at 4.78° North latitude, 7.01° East longitude and 468 m elevation above the sea level.

The breeding stocks were selected from the pool of 108 chicken hatched from 208 fertile eggs obtained from the improved indigenous chickens stocked by the Federal University of Agriculture (FUNAAB), Abeokuta Nigeria. Fifteen 15 normal feathered, 10 naked neck and 10 frizzle feathered hens and 10 cocks were selected as parents of the next generation. They were distributed into 7 breeding groups: Normal feathered cock with normal feathered hen (na × na ); Naked neck cock with naked neck hens (Na × Na); Frizzle feathered cock with frizzle feathered hens (Ff × Ff); Frizzle feathered cocks with Normal feathered hens (Ff × na); Naked neck cock with normal feathered hens (Na × na); Normal feathered cock with naked neck hens (na × Na); and Normal feathered cock with frizzle feathered hens (na × Ff).

The hens were five in each group and artificial insemination of the desired cock for each group was carried out twice a week before eggs are collected for incubation. Fertilized eggs were collected from 15 normal feathered, 10 frizzled and 10 naked neck hens of 30 weeks old for a period of four weeks. A total of 475 eggs were collected from all the birds for the period. Birds were inseminated with semen collected by abdominal massage as described by Hafez (1978). Insemination was done twice a week and eggs were collected daily from the hens. The eggs were stored at a temperature of 10°C, pedigreed by sire and dam lines by the use of a marker. The eggs were incubated and hatched with electrically heated (1000 egg capacity) incubator at a local hatchery (Gofon Veterinary Services) Owerri, Imo State. The incubation temperature and relative humidity were 37.5°C and 62.50%, respectively. Candling box measuring 0.44 × 0.44 × 0.44 m fitted with two 60 watt incandescent tungsten bulbs was used for candling of eggs. All infertile eggs and eggs with dead embryo were removed on the 21st day and chicks hatched were also recorded. The percentage of dead embryo was calculated as number of dead embryo divided by total number of eggs set. The fertility and hatchability percentage were calculated as follows:

% Fertility = (Total no. of fertile eggs/Total no. of egg set) × 100

% Hatchability = (Total no. of hatched eggs/Total no. of fertile eggs) × 100

.

% Embryo Mortality = (Total no. of Dead Embryo/Total no. of eggs set) × 100

The chicks were wing tagged at one day old and brooded in a deep litter house from 0 to 8 weeks age under standard management.

Data analysis

Data collected from the study was subjected to analysis of variance using the Generalized Linear Model (GLM) of Statistical Analysis Systems (SAS), 1999 using the sire/dam genotypes as the source of variation and means were separated using Duncan multiple range test of the same package. The linear model is stated as:

Yijkl = µ + Si + Dj + (SD)ij + Eijkl

where Y ijkl = dependent variable, µ = overall mean, Si = effect of the ith sire (I = 1,2,3), Dj = effect of the jth dam strain (j = 1,2,3), (SD)ij = effect of the interaction between sire and dam genetic group, and Eijkl = random error normally distributed with zero mean.

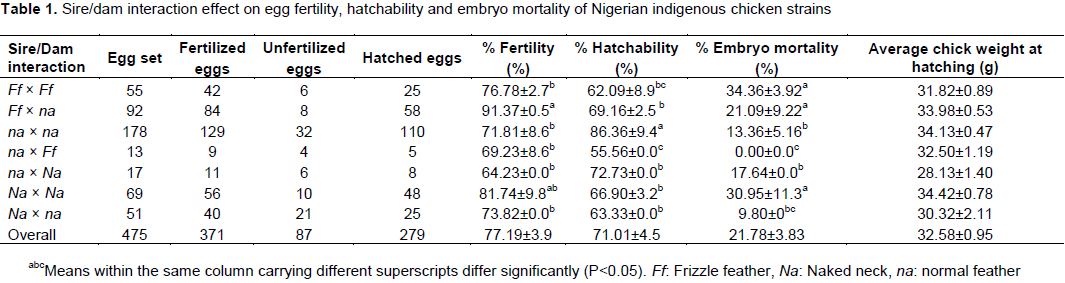

The result from this study revealed significant sire/dam interactive effect for fertility and hatchability of strains involving pure and crossbred indigenous chicken (Table 1). Fertility and hatchability is said to be environmentally influenced. Fertility and hatchability are major parameters of reproductive performance which are most sensitive to environmental and genetic influences (Stromberg, 1975) Fertility was the highest for Ff × na strain (91.37% and least for na × Na -64.23%). Pure frizzle feather and naked neck strains also recorded higher fertility than the pure normal feathered chicken. Fertility was 4.97% higher in frizzle gene and 9.93% higher in the naked neck than their normal feathered counterpart. This finding is consistent with earlier reports (Horst, 1989; Peters et al., 2008). This may be due to the superiority of the adaptive genes of frizzling and naked neck genes and the fact that the frizzle gene produced 13.98% more semen and the naked neck gene also had 18.68% higher concentrated semen than the normal feathered gene (Ajayi et al., 2011). Hatchability percentage on the other hand was the highest in the pure normal feathered chicken with value of 86.36%, whereas lower values of 62.09 and 66.90% was recorded for pure frizzle and naked neck strains, respectively. The crossbred strains ranged between 55.56 and 72.73% in hatchability percentage. This result is consistent with the findings of Peters et al. (2008) who reported the highest hatchability for normal feathered genetic group followed by frizzle and naked neck genetic group with corresponding values of 89.75, 84.62 and 82.63%, respectively. Many factors may have contributed to the failure of fertile eggs to hatch which include lethal genes, insufficient nutrients in the egg and exposure to conditions that do not meet the needs of the developing embryo (King’ori, 2011).

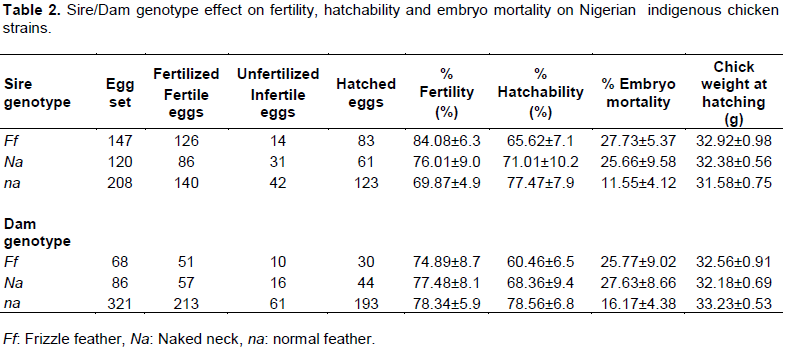

The pure normal feathered genetic group also had the least embryo mortality (13.65%) when compared with the pure frizzle and naked neck genetic groups (34.36% versus 30.95%) and the crossbred involving these major genes. According to Merat (1986), the increase in embryonic mortality up to 10% found in pure strain Na/Na and to a large extent Na/na put them at a disadvantage to the normal feather birds. The low hatchability and high embryonic mortality as observed in pure frizzle and the naked genes in this study may be the reason for continuous reduction of chicken population among poultry birds. There is however no significant difference in chick weight at hatching for both pure and crossbred chicken. Chick weight ranged from 28.13 g for na × Na to 34.13 g for na × na strain. Sire and dam genotypes showed no significant difference (P>0.05) for percent fertility and hatchability of eggs (Table 2). This result contradicts the reports of Peters et al. (2008) who found significant difference between sire and dam genotypes. Embryo mortality and chick weight at hatching were not also significant (P>0.05). The difference found in the two studies may be attributed to larger number of birds used in the former than the latter and also to the different environmental management of the birds.

In conclusion, this study revealed that indigenous pure and crossbred frizzle and naked neck chicken had reduced fertility and hatchability and also higher embryo mortality than their normal feathered counterpart. This may be the reason for the continuous reduction of their population among poultry birds. There is need for their adequate conservation so that the frizzle and naked neck chicken will not go into extinction.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Ajayi FO (2010). Nigerian Indigenous Chicken: A valuable genetic resource for meat and egg production. Asian J. Poultry Sci. 4(4):164-172.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Ajayi FO, Agaviezor BO, Ajuogu PK (2011). Semen Characteristics of Three Strains of Local Cocks in the Humid Tropical Environment of Nigeria. Int. J. Anim. Vet. Adv. 3(3):125-127.

|

|

|

|

|

Benítez F (2002). Reasons for the use and Conservation of Some Local Genetic Resources in Poultry. 7th World Congress on Genetic Applied to Livestock Production, August 19-23, 2002, Montpellier, France.

|

|

|

|

|

Dana N, van der Waaij LH, Dessie T, van Arendonk JAM (2010). Production objectives and trait preferences of village poultry producers of Ethiopia: implications for designing breeding schemes utilizing indigenous chicken genetic resources. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 42:1519-1529.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Eslick ML, McDaniel GR (1992). Interrelationship between fertility and hatchability of eggs from broiler breeder hens. Appl. Poult. Sci. 15:123-214.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

FAO (2010). Chicken genetic resources used in smallholder production systems and opportunities for their development, by P. Sørensen. FAO Smallholder Poultry Production Paper No. 5. Rome.

|

|

|

|

|

Gueye EF (2009). The role of networks in information dissemination to family poultry farmers. World's Poult. Sci. J. 65:115-124.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Hafez ESE (1978). Reproduction in Farm Animals. 2nd Edn., Education Page. Lea and Febiger, Philadelphia. P 237.

|

|

|

|

|

Horst P (1989). Native fowl as a reservoir for genomes and major genes with direct effect on the adaptability and their potential for tropical oriented breeding plans. Arch. Geflugella 5313:63-79.

|

|

|

|

|

King'ori AM (2011). Review of the Factors That Influence Egg Fertility and Hatchabilty in Poultry. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 10(6):483-492.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Merat P (1986). Potential usefulness of the Na (Naked neck) gene in poultry production. World's Poult. Sci. J. 42:124-142.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Peters SO, Ilori BM, Ozoje MO, Ikeobi CON, Adebambo OA (2008). Gene segregation effects on fertility and hatchability of pure and crossbred chicken genotypes in the humid tropics. Int. J. Poult. Sci. 7(10):954 -958.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Pym RAE, Guerne B, Hoffmann E (2006). The relative contribution of indigenous chicken breeds to poultry meat and egg production and consumption in the developing countries of Africa and Asia. Proceedings of the XII European Poultry Conference, 10–14 September 2006, Verona, Italy. CD-ROM.

|

|

|

|

|

RIM (1992). Nigeria Livestock Resources. Volume II: National Synthesis Annex Resource Inventory Management Limited. p 472.

|

|

|

|

|

SAS (1999). SAS User's guide version 8. Statistical Analysis System Institute. Inc. Cary, NY.

|

|

|

|

|

Stromberg J (1975). A guide to better hatching. Stromberg Publication Co. Iowa, USA. pp. 8-25.

|

|