ABSTRACT

The welfare of an animal relates primarily to its ability to cope, firstly with its external environment, such as housing, handing by humans, weather and the presence of other animals, and secondly with its internal environment, such as specific injuries or illnesses and nutritional status. Direct animal measurements are good indicators of animals’ current well-being and help identify longer term animal welfare problems. These should integrate long term consequences of past husbandry practices, be non-intrusive, and free from observer bias. Many welfare protocols are based on the five “basic freedoms” for good animal welfare, namely freedom from hunger and thirst, discomfort, pain, fear and distress and freedom to express normal behaviour. To be objective, welfare indicators need to be quantifiable and scientifically based. This review presents a list of key performance indicators of stock welfare specifically relevant to tropical small holder dairy farms. They can be separated into six different categories, such as nutrition, reproduction, disease, external appearance, environmental injury and behaviour. The review also presents a standard approach for estimating an animal welfare index well suited to the thousands of smallholder dairy farmers throughout tropical Asia.

Key words: Dairy cattle, welfare protocols, tropics, small holder welfare index.

The welfare of an animal relates primarily to its ability to cope, both with its external environment, such as housing, handing by humans, weather and the presence of other animals, and with its internal environment, such as specific injuries or illnesses and nutritional status. Welfare refers not only to the internal and external environments of animals, but how they feel (Phillips, 2002). These feelings can be negative, including pain, fear and hunger, or they can be positive, including calmness and happiness.

The health and welfare of an animal is closely linked with the health status of an animal influencing its welfare,

and its welfare influencing its health (von Keyserlingk et al., 2009). Cattle kept in poor or chronically stressful conditions are more susceptible to disease and reduction in the level of productivity. Cattle with illnesses and injuries, particularly chronic ones, can often be classified as having poor welfare. Production can also be included in this relationship, with healthy and happy cattle being more productive.

European Food Safety Authority (2009) state that long term genetic selection for high milk yield in dairy cows is a major factor contributing to poor welfare, in particular health problems such as lameness, mastitis, metabolic instability and longevity. In other words, we breed cows to produce more and more milk at the expense of their welfare. This is particularly relevant to poorly resourced dairy farmers and those who do not fully understand the impact of these genetically selected high milk yields can have on the nutrient demands of cows. These nutritional deficits then infringe on their welfare making them more susceptible to metabolic and reproductive problems.

According to the World Organisation for Animal Health (OIE, 2013) an animal is in a good state of welfare if it is healthy, comfortable, well nourished, safe, able to express its innate behaviour and is not suffering from negative states such as pain, fear, and distress. While the welfare of an animal is a dynamic thing dependent on changes in its health and environment, some simple, fundamental features will guarantee good welfare. These are: good hygiene, having continuous access to clean water, stable social groups and the provision of preventive veterinary care. Good animal welfare then requires disease prevention and veterinary treatment, appropriate shelter, management, nutrition, humane handling, transport and eventually, humane slaughter.

While the above definitions are accepted internationally, what people interpret to be acceptable animal welfare can be influenced by many factors including personal values, religion, nationality, gender, previous experiences, age, socio-economic status, education etc. The author of this review has recently written a reference book on the key aspects of welfare of stock on smallholder dairy farms in tropical Asia (Moran and Doyle, 2015).

WHY ANIMAL WELFARE IS IMPORTANT

Not only is it important to understand what welfare is, but we also need to know why it is of importance. Animal welfare is fundamentally linked to animal health and production (Moberg, 2001). Both clinical and sub-clinical disease states will compromise the welfare of animals. For example, lameness causes a cow to feel pain and as a result, this will impact on her ability to feed, rest, move and cope with other illnesses and stressful situations that she experiences. Poor welfare can also have a negative impact on the health of a cow. Stressful situations, such as negative treatment by a stockperson or ongoing aggressive interactions with other animals in the herd, will result in physiological and behavioural changes in the animal that are aimed at helping it to deal with the stress. If the stressor is prolonged, becoming chronic, these physiological responses can impact upon the immunity of the cow, making her more susceptible to disease. Poor welfare is also linked to reduced productivity, inhibiting the capacity for the cow to reproduce, reducing milk yields and body condition. For example, illness can reduce feed intake and divert resources from production to fighting infection while cattle experiencing fear during handling will also have reduced milk yields. Public perceptions of farm animal welfare issues have the potential to markedly affect the security and sustainability of our livestock industries. Nationally and internationally, these societal pressures are playing increasingly significant roles in determining how animals are managed and products are marketed while scientific findings assist development of welfare assessment, practice and improvement.

WHO SHOULD BE RESPONSIBLE FOR STOCK WELFARE?

There is considerable public debate about who should ultimately be responsible for stock welfare. Many of the breeder stock purchased specifically for increasing herd sizes on tropical small holder dairy farms in Asia did not originate from these countries and are frequently imported from temperate, developed dairy industries with a high regard for animal welfare. Whether it is appropriate for such poorly adapted stock to be transported direct from developed farms in temperate regions to often subsistence small holder dairy (SHD) farms in the humid and dry tropics has been a subject of continual discussion such as Moran (2012). Once the decision has been made and the funds allocated, it should be purely a commercial decision between the purchasing and the selling countries. However the debate does not stop at this point. Under what stipulations and what responsibilities should the exporting country take for the welfare of such stock once they arrive within the importing country? Should animals born and bred in a country with often more stringent stock welfare philosophies and practices be exported to countries with often less sophisticated approaches to stock welfare?

In certain developed dairy industries, such as Australia, there is considerable discussion in recent years between the various dairy stakeholders and the general public about the legitimacy of this trade. In such countries, lobby groups are becoming quite vocal in their attempts to influence public accountability in stock welfare practices. They are gradually impacting on such practices in the more intensive animal industries, such as the gradual removal of sow crates in pig production and of battery cages in poultry production systems. Such lobby groups are said to mainly represent societies more extreme opinions in animal farming, such as those promoting vegetarian lifestyles in which animal farming has no part.

With regards cattle welfare in Australia, these groups have been successful in reflecting the opinions of the general public such that in 2011, a television documentary program led to the Federal government legislating a complete ban on exporting live cattle for slaughter to Indonesia for several weeks, which had ramifications on the beef cattle breeder industry for several years at least. For the industry to be recommenced on a more “acceptable” footing, a series of measures were introduced to pass the ultimate responsibility of the cattle welfare from the public (government) to the private (export agents) sector. To date (early 2015) this only covers the export of cattle for fattening and slaughter but is likely to be extended to the export of cattle (both dairy and beef) for breeding purposes.

The responsibility of ensuring acceptable stock welfare practices to slaughter cattle, which are slaughtered within a few weeks of arrival in the importing country, is relatively easy to monitor. However when breeder cattle are exported to developing countries, often with different societal standards of acceptable stock welfare practices, such a responsibility could be more difficult to monitor because of the nature of the dairy industries, with thousands of poorly resourced, smallholder farmers, and the length of time that such monitoring would have to take place during the life of such cattle (that is several years rather than several weeks).

This is an ongoing concern within Australia’s beef and dairy cattle industries, because of the increasing size of these relatively new export industry sectors, which number up to one million beef steers per year for slaughter and 100,000 dairy and beef heifers per year for breeding purposes. The live breeder cattle export trade has become a “win win” situation for both the purchasers and the suppliers. Not only does it increase national herd sizes hence domestic milk production in the purchasing countries, it also provides an additional source of income for dairy farmers in the supplying countries. This was particularly relevant in Australia during the extensive 2008 to 2009 national drought as it provided additional cash flow for dairy farmers while they were suffering markedly reduced income streams. In the process of addressing societies’ concerns about acceptable cattle welfare practices, new capacity building programs have been introduced within the importing countries. Furthermore, there is now extra vigilance by both public and private sectors particularly those agencies with high profiles in stock welfare, in the stock handling and herd management practices in these countries. This can only lead to improvements in animal welfare, for the better well-being of the dairy stock.

INDICATORS OF ANIMAL WELFARE

There are many different methods that can be used to measure an animal’s welfare and a balance needs to be sought so that enough measures are taken, scientifically-based, and that the data can be collected in a timely manner. When choosing direct measures of welfare, several factors need to be considered. Indicators should integrate the long-term consequences of past husbandry practices. They should be non-intrusive so as to cause minimal disturbances to the animals’ natural behaviour. They must be reasonably free of observer bias and should highlight welfare problems and identify failures in farm management that contributed to such problems. Welfare observations should then be centred on three aspects:

(1) Validity. What does this indicator tell us about the animal’s welfare state?

(2) Repeatability. Do different observers always see the same problem?

(3) Feasibility. How easy is it to record this indicator?

Most approaches to welfare assessment are based on indicators of reduced welfare. Understandably this is because the greatest compromise to welfare lies with negative situations. However, it is worthwhile putting more emphasis on indicators of good welfare. Environmental control and positive social interactions would be considered the main components of good welfare. Social and non-social play in calves or social licking in adult cows are examples of positive social activities, and stock are only motivated to perform such behaviours once their primary needs are satisfied. Animal welfare research and assessment is moving in this direction and more objective indicators of positive welfare will be developed with time.

Traditionally farm animal welfare audits have focused on measurements of resources provided to the animal such as housing-related facilities, management practices and human-animal relationships. These are often difficult to quantify and may not necessarily result in improved standards of animal welfare, although they can indicate risks or reasons for the animal’s welfare. More direct animal measurements such as behaviour and health would be better indicators of their current well-being and help identify longer term animal welfare problems.

THE FIVE BASIC FREEDOMS OF LIVESTOCK

The welfare requirements of cattle can best be summarised in the “five freedoms” (Farm Animal Welfare Council, 2009). These were originally developed by the UK government as a part of a report into farm animal welfare (Brambell, 1965) but are now applied to all animals under the care of humans. These five freedoms are as follows:

(1) Freedom from hunger and thirst, through ready access to fresh water and a diet to maintain full health and vigour.

(2) Freedom from discomfort, through provision of appropriate shelter and comfortable resting areas.

(3) Freedom from pain, by prevention and, when sick, rapid diagnosis and treatment.

(4) Freedom from fear and distress by ensuring conditions which avoid mental suffering

(5) Freedom to express normal behaviour by providing

adequate space, proper facilities and the company of other animals.

These five freedoms address both physical fitness and mental suffering and are best viewed as a practical, comprehensive checklist to assess the strengths and weaknesses of any husbandry system. There is a hierarchy of needs of cattle and the five freedoms should not be taken to imply that all animals should be free from exposure to any stress, ever. The aim is not to eliminate stress but to prevent suffering and progress towards improved welfare by providing for the animal’s needs. Suffering occurs when animals fail or have difficulty in coping with stress. All dairy cattle management and housing systems should be designed, constructed, maintained and managed to assist with these “five freedoms”.

KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS OF CATTLE WELFARE

Key Performance Indicators (KPI) can act as a guide to help farmers diagnose the strengths and weaknesses in their dairy enterprise. Expressed simply, KPIs are then diagnostic tools to help identify weaknesses adversely affecting farm performance. Farmers can use these indicators to identify areas of animal welfare weaknesses, and help to give them an idea of their performance in relation to other farms. Comparing between farms can be a useful way to affect a change in practice as farmers are more likely to try to improve their management practices if they can identify where they are, compared to others, in terms of welfare and productivity. There are a variety of KPIs available for small-holder dairy farmers that cover health, productivity and welfare, and many of these have been highlighted by Moran (2009).

The Welfare Quality (2009) project has listed 12 such KPIs that relate to animal welfare. This is specifically for the first four “basic freedoms of livestock”, as the fifth freedom, to express natural behaviour, should be assured if all else is satisfied. These 12 KPIs are:

(1) Animals should not suffer from prolonged hunger

(2) Animals should not suffer from prolonged thirst

(3) Animals should be comfortable, especially within their lying areas

(4) Animals should be in a good thermal environment

(5) Animals should be able to move around freely

(6) Animals should not be physically injured

(7) Animals should be free of disease

(8) Animals should not suffer from pain induced by inappropriate management

(9) Animals should be allowed to express natural, non-harmful, social behaviours

(10) Animals should have the possibility of expressing other intuitively desirable natural behaviours such as exploration and play

(11) Good human-animal relationships are beneficial to the welfare of animals

(12) Animals should not experience negative emotions such as fear, distress, frustration or apathy.

Unfortunately they are without quantitative descriptors, making it difficult to ensure repeatability of measures if using this list alone.

Similarly to the Welfare Quality project, Webster (2005) presented a list of the “top ten” indicators of welfare of dairy cows developed by a team of veterinarians and animal production scientists in the United Kingdom, these being:

(1) Observing lameness

(2) Examining health records

(3) Observing disease

(4) Observing mastitis

(5) Observing general demeanour

(7) Scoring body condition

(8) Observing stockperson ship

(9) Observing lying behaviour

(10) Examining production records

(11) Observing skin lesions

QUANTIFIABLE WELFARE INDICATORS

To be objective, welfare indicators need to be quantifiable. The following is a comprehensive list of such indicators. This list has been selected to be specifically relevant to tropical small holder dairy farms and has been separated into six different categories. These include the nine of the cow signals as listed by (Hulsen, 2011) for which scoring systems have been described by Moran and Doyle (2015). This detailed list utilises farm records as well as direct observation to assess welfare of the herd.

Nutrition

(i) Prolonged hunger; body condition score; % of very lean cows and % very fat cows

(ii) Rumen score; % cows with deeply hollow rumens

(iii) Dung score; % cows with any coarse particles in their dung and a consistency of stiff balls like horse manure

(iv)Prolonged thirst; number of stock per drinker or per cm of drinking trough, water flow and cleanliness of drinkers; this is not relevant to tie stall systems.

(v) Milk fever; % incidence/year

(vi) Metabolic diseases; % incidence/year, (such as ketosis or hypomagnesaemia, but not milk fever, mastitis or lameness).

Reproduction

(i) Assisted calving; % cows calving/year

(ii) Conceptions to first service; % cows/year

(iii) Average days from first service to conception

(iv) Average age at first calving

Disease

(i) Locomotion score; % cows moderately to severely lame

(ii) Hoof score; % cows with severe hoof inflammation

(iii) Teat score; % cows with rough callous ring around the teat ends

(iv) Mastitis, clinical cases; %/year

(v) Mastitis, subclinical cases; %/year

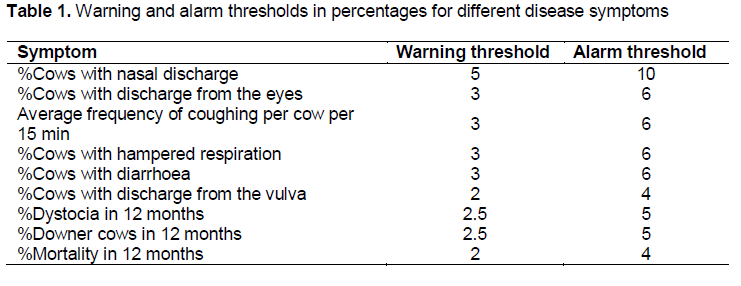

(vi) Indicators of disease (Table 1); mean number of coughs per cow per day, % on farm mortality, % downer cows, % cows with nasal discharge, % cows with hampered respiration

(vii) Disease in calves; % calves with diarrhoea, % calves requiring veterinary attention

(viii) Pre-weaning mortality; % calves died prior to weaning

(ix) Sudden deaths/casualties; % per year

(x) Dull/obviously sick cows; % cows per year

(xi) Indicators of pain; methods and use of anaesthetics and analgesics for disbudding, dehorning and tail docking

External appearance

(i) Cow cleanliness score; % cows with excessively dirty lower hind legs, hindquarters or udders

(ii) Cows with hair loss in lower limbs; % cows per year.

Environmental injury

(i) Leg score; % cows with severe rotation of their feet

(ii) Cows with swollen hocks; % cows per year

(iii) Cows with ulcerated hocks; % cows per year

(iv) Cows with non-hock traumatic injuries; % cows

(v) Ease of movement in laneways; % cows slipping and falling.

Behaviour

(i) Resting behaviour; % cows lying partly or completely outside resting area

(ii) Social behaviour; number of head butts and displacements/cow/hour

(iii) Flight distance, measured by approaching cows at the feed trough from a distance of 2.5 m and measuring the distance between the hand and muzzle at the moment the animal withdraws; % of cows 0 to 10 cm, 10 to 50 cm, 50 to 100 cm and >100 cm

(iv) Idle cows; % cows standing but performing no activity, such as rumination

(v) Rumination; % cows standing or lying that are ruminating

(vi) Rising restriction; % cows showing severe difficulty in rising, or hitting fittings as they rise or seen to be “dog sitting”

(vii) Heat stress; % cows with respiration rates exceeding 70 or 100 breaths per min

(viii) Cow comfort index; % cows standing or lying in free stalls.

THRESHOLDS FOR INITIATING HERD HEALTH PLANS

Some diseases affect few animals in a herd while others can spread very easily between animals. Welfare Quality (2009) has documented the incidence of symptoms of disease in terms of warning and alarm thresholds. The alarm threshold is the minimum value for a decision to put a health plan in place on the farm while the warning threshold is half the alarm threshold. These are presented in Table 1.The following checklist has been taken from the Assure (2010) program. It uses several of the measures detailed above and focuses more closely on direct observations of individuals and the herd to assess welfare. The measures chosen for this checklist specifically allow comparison between farms with different management systems. They also allow for the assessment of welfare on an individual animal level, as well as assessing the entire herd. This type of checklist is essential when you wish to conduct a brief, yet objective evaluation of welfare, or when herd records are available. Further details on these measurements (with may include photographic standards) are provided by Moran and Doyle (2015).

Individual measures

(i) Mobility: observe cow on a hard non-slip surface. Monitor the cow for 6 to 10 uninterrupted strides, observing the cow from the side and the rear.

(ii) Body condition: visually assess the cow from behind and from the side, the tail, head and loin areas.

(iii) Hair-loss, lesions and swelling: visually assess specific regions on the animal from the side. Areas include the head, shoulders, neck, flank, side, udder, hindquarter, front leg, and hind leg to hock. Scoring ranges from no to slight skin damage to lesion or swelling.

(iv) Dirtiness: Visually assess the lower hind legs including the hock, the hindquarters and the udder for dirtiness. Scores are clean, dirty or very dirty.

Herd measures

(i) Mobility and lameness management: assess the management strategies of 3 or more lame cows, including any in a hospital pen

(ii) Lying comfort: assess the number of cows not lying correctly (partly or completely outside the cubicle)

(iii) Broken tails: record numbers of cows with bent, short, injured, and broken tails

(iv) Response to stock person: observe the response of the cattle to the stockperson as they approach and interact. Scored as sociable, indifferent or cautious.

(v) Cows needing further care: assess the whole herd and record any sick or injured cows that need further intervention.

Recorded measures

(i) Mobility and verifying self-assessment: verify the stockperson’s ability to identify lame cows

(ii) Mastitis: check farm records for incidences

(iii) Heifer and cow survivability: check farm records.

DEVELOPING A SYSTEM FOR DAIRY COW WELFARE ASSESSMENT

To improve animal welfare, farmers need to be able to assess their development over time, and then respond accordingly. Rousing et al. (2000) provide such a protocol based on four information sources namely:

(i) System: With loose housing, the welfare indicators would include the dimensions, partitions and surfaces of cow stalls, their physical positioning within the housing system, the laneways and exercise areas, the collection area and layout of the milking area and the design and placement of the feeding and watering facilities.

(ii) Management: This is all based on ensuring the care required to create and sustain good stockpersonship and welfare in the herd. For example, there should be appropriate and efficient designs of shed equipment for proper handling and inspection routines while other indicators would include stocking density (for feeding, drinking and resting), quantity and quality of bedding material, the availability of calving and hospital pens, the method of feeding (feed quality and whether it is restrictive or ad libitum) and the calving cycle (which can lead to peak stock and workloads).

(iii) Animal behaviour: Such indicators refer to social behaviour, human-animal relationships and existing resting or rising behaviour.

(iv) Animal health: These indicators focus on the cause of pain and discomfort to the animal, such as extreme body condition, skin injuries and disorders, udder and teat lesions, lameness, hoof disorders, other clinical diseases and the case history of any culled animal.

A SIMPLIFIED SCORING SYSTEM FOR ASSESSING DAIRY COW WELFARE

Moran and Doyle (2015) have incorporated the key issues highlighted above into a simplified “farmer friendly” scoring system to assess dairy cow welfare. This is presented in Tables 2 and 3, and we believe it is well suited to the thousands of SHD farmers throughout tropical Asia. It contains 36 questions or observations, is based on the “five freedoms of animal welfare” and addresses both tethering and loose housing. The questionnaire is a combination of different auditing systems for dairy cattle, including those from World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA) (Blaszak, 2011), Assure (2010), Welfare Quality (2009) and FAO (2011). It has been developed to focus more on good rather than poor animal welfare, so the higher the score, the better the welfare for the animals. Because many SHD farmers have few milking cows, we have used 0, 30 and 90% of the herd as criteria of good stock welfare practices.

How to use this scoring system

(i) Complete the details on farm. Animal numbers are important for score calculations.

(ii) Each of the “five basic freedoms of animal welfare” are assessed.

(iii) Each measure is assigned a total of 1.0. The total for each freedom is scored according to the number of measures answered. If the measure does not apply to that particular farm (for example it may not have any young calves), this should not be taken into account in the total.

(iv) For each measure, when ‘yes’ applies to more than 90% of animals, 1.0 points are scored. When ‘yes’ applies to 30% or less of animals, 0.0 points are scored.

When ‘yes’ applies to 30 to 90% of animals, 0.5 points are scored.

(v) Photographic standards for scoring body condition, rumen fill, cleanliness, locomotion, hooves and teat scores are provided Moran and Doyle (2015).

Once this form was developed, the next step is to make a value judgement as to the quality of animal welfare on that particular farm. This step is still evolving because we firstly need to collect sufficient on-farm data to quantify the range of farm assessment scores likely to be encountered; this may lead to some modifications and improvements in the type of data collected. Not every question can be answered for every farm, so it is not possible to develop an identical generic summary form for every farm visit. Table 3 provides a framework to calculate the animal welfare status of each farm visited. It is based on calculating a single value for each of the five freedoms then developing an overall stock welfare index based on equal weightings of each of these five freedoms.

This scoring system makes a value judgement that the five freedoms are of equal importance hence have equal impact on the cow’s well-being. This assumption may require further discussion and feedback from some of the world’s animal welfare experts. Table 3 is a “work in progress” but we believe it forms the basis of a relatively robust, yet quick, assessment of animal welfare on an individual small holder or large scale farm.

Other dairy cow welfare scoring systems have been developed such as Rousing et al. (2000) and Whay et al. (2003) but they require high time inputs and written records of cow performance and health, hence are more suited to larger dairy herds. We have developed a simplified system which can be completed on any small holder farms within an hour or so. Being able to quantify evidence of poor stock welfare practices is the first step in addressing these key issues on any farm. The next step is to develop strategies to improve their well-being under the existing farm conditions. For small holder dairy farmers in Asia, this is discussed at length by Moran (2012) and Moran and Doyle (2015).

The author has not declared any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Assure W (2010). Advancing animal welfare assurance. Collaborative project of University of Bristol, RSPCA and Soil Association of UK. |

|

|

|

Blaszak K (2011). WSPA Report: Dairy cattle industry and welfare in Indonesia. |

|

|

|

Brambell FWR (1965). Report of the technical committee to enquire into the welfare of animals kept under intensive livestock husbandry systems. Command P. 2836, HMSO London, UK. |

|

|

|

European Food Safety Authority, EFSA (2009). Scientific opinion on the overall effects of farming systems on dairy cow welfare and disease. EFSA J. 1143:1-38 |

|

|

|

Farm Animal Welfare Council, FAWC (2009). Five Freedoms. |

|

|

|

Food and Agriculture Organisation, FAO (2011). Guide to good dairy farming practices. Animal health and production guidelines no 8. FAO and IDF, Rome, Italy. |

|

|

|

Hulsen J (2011). Cow signals. A practical guide for dairy farm management. Rood Bont Publishers, Zutphen, Netherlands. PMid:22185614. |

|

|

|

Moberg GP (2001). Biological Response to Stress: Implications for Animal Welfare. In G. P Moberg & J. A Mench (Eds.), The Biology of Animal Stress. Wallingford, Oxon, UK: CAB International |

|

|

Moran JB (2009). Key performance indicator's to diagnose poor farm performance and profitability of smallholder dairy farmers in Asia. Asian-Aust. J. Anim. Sci. 22:1709-1717.

Crossref |

|

|

|

Moran JB (2012). Managing high grade dairy cows in the tropics. CSIRO Publications, Melbourne, Australia. |

|

|

|

Moran JB, Doyle R (2015). Cow talk. Understanding dairy cow behavior to improve their welfare on small holder farms in tropical Asia. CSIRO Publications, Melbourne, Australia. |

|

|

|

Office International des Epizooties, OIE (2013). Terrestrial animal health code. World Organisation for Animal Health, Paris, France. |

|

|

Phillips C (2002). Cattle behaviour and welfare. 2nd Ed. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK.

Crossref |

|

|

|

Rousing T, Monde M, Sorensen JT (2000). Indicators for the assessment of animal welfare in a dairy cattle herd with a cubicle housing system. In Improving health and welfare in animal production, Ed Blokhuis, H. J., Ekkel, E. D. & Wechsler, B. EAAP Publication No 102:37-44. |

|

|

|

von Keyserlingk MAG, Rushen J, de Passille AM, Weary DM (2009). Invited review: The welfare of dairy cattle - Key concepts and the role of science. J. Dairy Sci. 92:4101-4111. |

|

|

|

Webster J (2005). The assessment and implementation of animal welfare: theory into practise. In: Animal Welfare: global issues, trends and challenges. Revue scientifique et technique, Office International des Epizooties 24(2):723-734. |

|

|

|

Welfare Quality (2009). Welfare Quality assessment protocol for cattle. Welfare Quality Consortium, Lelystad, Netherlands. |

|

|

Whay HR, Main DCJ, Green LE, Webster AJF (2003). Assessment of the welfare of dairy cattle using animal-based measurements: direct observations and investigations of farm records. Vet. Rec. 153(7):197-202.

Crossref |