ABSTRACT

Informed by the Big Five personality and General Aggression Model (GAD), this study sought to examine the relationship between the Big Five personality traits and socio-demographic determinants of aggression among adolescents in Kenya. The respondents were adolescent girls aged 12-17 (n=86) admitted to the rehabilitation institutions. An adapted Aggression Questionnaire (A.Q.), the Big Five Inventory (BFI), and Socio-Demographic Questionnaires were used to gather data. Results showed a significant weak negative correlation between extraversion personality traits and physical aggression (r= -0.051, p>0.05), as well as a weak, but significant, negative correlation between extraversion personality traits and verbal aggression (r= 0.282, p<0.05). In addition, the agreeableness was not significantly correlated to physical aggression (r=0.001, p >0.05), while the neuroticism/emotional stable personality traits had a weak, but significant, negative association with physical aggression (r= -0.257, p<0.05), verbal aggression (r=-0.241, p<0.05) and hostility (r=-0.369, p<0.05. The findings imply that various personality types will respond aggressively or non-aggressively to situations. In this study, the adolescent girls who were in neuroticism personality type were more likely to display various forms of aggression compared to those who were in agreeableness, conscientiousness and opens types. Further, this study concludes that not all extraverted types are likely to become physically aggressive, although they are more likely to become verbally aggressive.

Key words: Adolescent; aggression; aggressive behaviors; personality; socio-demographic; Kenya.

Aggressive behavior in children and adolescents is often a concern for parents and teachers. Studies show that aggressive behaviors during adolescence may have long-term effects (Broidy et al., 2003; DeWall et al., 2011). Aggression is defined as a behavioral act that results in hurting or harming others to increase the one’s social dominance in relation to others (Anderson and Bushman, 2002; Crick et al., 1999; Ferguson and Beaver, 2009; Zirpoli, 2008). Kruti and Melonashi (2015) define aggression as an emotional state accompanied by a desire to attack others driven by internal and external factors. Bushman and Huesman (2010) state that aggression can be either direct or indirect, where direct aggression is characterized by physical forms such as kicking, hitting, punching, and biting, while indirect aggression is characterized by social isolation, social exclusion, and using threats. Further, Crick and Grotpeter (1995) state that relational aggression or social aggression intentionally aims to harm another person's social relationships, feelings of acceptance, or inclusion. The effects of relational or social aggression may linger longer than those caused by other forms of aggression, such as physical or verbal aggression (Chen et al., 2010; Lagerspetz et al., 1988).

Socio-demographic determinants of aggression

Family types and adolescent aggression

Okon et al. (2011) posit that aggression may result from early childhood socialization. Family processes and dynamics can either promote or maintain aggressive behaviors. Henneberger et al. (2016) found that family functioning, family cohesion, and parental monitoring were significant determinants of adolescents’ physical aggression among Hispanic and African American youth.

Studies have also shown that the type of family influences family functioning. Single-parent families will have different forms of family functioning and family cohesion than families where both parents are present. Therefore, family cohesion, a felt sense of shared affection, support, and caring within the family will vary from one family to another (Rodríguez-Naranjo and Caño, 2016; Moos and Moos, 1976). Further, the family type will also determine the type of parental monitoring which constitutes parenting behaviors, such as paying attention to and tracking children's whereabouts, activities, and adaptations (Dishion and McMahon, 1998). Further, Rodriguez-Naranjo and Cano (2016) found that family functioning practices such as problem-solving, communication, roles, affective responsiveness, affective involvement, and behavior control were significantly correlated to specific aggressive behavior delinquency.

Yizhen et al. (2006) argue that family factors relevant to adolescent aggression development such as maternal education, paternal occupation, parental child-rearing attitude, and patterns are significant predictors of family type. Therefore, the risk factors of adolescent aggression are likely to be prevalent where there are dysfunctional families, low-income family cohesion, and inadequate parental monitoring that predispose the adolescents to aggressive behaviors (Bandura, 1978; Ehrensaft and Cohen, 2012; Nocentini et al., 2019).

Gender differences in aggression

Gender differences in aggression have been reported in several studies. Anderson and Bushman (2002) and Crick and Grotpeter (1995) found that men tend to engage more in direct aggressive behavior physical and verbal than women. Crick and Grotpeter (1995) found that indirect or relational aggression that affects social adjustment was higher among adolescent girls than adolescent boys. They reported that boys are more likely to engage in direct physical and verbal aggression, while girls were more likely to engage in verbal aggression. Further, boys growing in dysfunctional families characterized by frequent violence, divorce, or separation are more likely to become physically aggressive than girls who tend to become more verbally aggressive (Salmivalli and Kaukiainen 2004; Garnefski and Okma, 1996; Viale-Val and Sylvester, 1993).

Social-economic status and adolescent aggression

Several studies have found a consistent relationship between low-income family status and aggressive behavior in adolescents (McGrath and Elgar, 2016; Mejovsek et al., 2000). High-income families have been positively related to aggression compared to middle and low income (Rahman and Huq, 2005). Huesmann and Taylor (2006) investigated the relationship between anger that leads to aggression and found that respondents from the upper class manifested more aggressive behaviors than those from the lower and middle classes. Krieger et al. (1997), state that socio-economic status (SES) is an economic and sociological combined total measure of an individual or family's economic and social position in relation to others, based on income, education, and occupation. Socio-economic status is typically broken into three levels, namely high, middle and low. Studies show a consistent relationship between low socio-economic status and aggressive behavior of children and adolescents (Dodge and Price, 1994; Mejovsek et al., 2000). Rahman et al. (2014) further argue that the parent's level of education influences the socio-economic status. Higher levels of education are associated with better economic status.

Families with enhanced income are more likely to provide for their children. Rahman and Huq (2005) found that aggression in adolescent boys and girls was highly related to socio-economic status (SES). The adolescent boys and girls from the middle and low SES families were more aggressive than those from higher-income families. Liu et al., (2013) found that lower and middle-class adolescents were more likely to manifest verbal aggression than upper-class counterparts. Gallo and Matthews (2003) reported that adolescents from the lower class were more likely to be hostile and engage in physical aggression than those from the upper class.

Personality types as a determinant of aggression

Studies show that aggression and personality variables predict aggressive behaviors (Anderson and Huesmann, 2003). Roberts et al., (2009) further defines personality traits as the relatively enduring patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that reflect the tendency to respond in specific ways under certain circumstances (Soto et al., 2016). In the following section, the authors examine the personality types using the Five-Factor Personality and the General Aggression Model.

Big five-factor personality traits and aggression

The five-factor personality model has a set of five broad trait dimensions - extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism (emotional stability), and openness – which influence aggression. Cavalcanti and Pimentel (2016) showed a direct effect of neuroticism extraversion and agreeableness in physical aggression, but the indirect effects of neuroticism, opening, and agreeableness in physical aggression. Barlett and Anderson (2012) argue that aggressive behavior in the Big 5 traits depends on the specific type of aggressive behavior and the trait measured. The openness and agreeableness types were directly and indirectly related to physical aggression and were only indirectly related (through aggressive attitudes). Similarly, neuroticism was both directly and indirectly (through aggressive emotions) related to physical aggression, but not violent behavior.

General aggression model

The General Aggression Model (GAM) provides an integrative and comprehensive framework for examining human aggression (Anderson and Bushman, 2002). The model adopts a dynamic, episodic, and person-in-situation approach to explain aggression. During an episode of aggressive behavior, three phases emerge, namely inputs, routes, and outcomes. The input phases focus on the influence of personal factors and situational variables; the routes phase focuses on how input variables influence affect, cognition, and arousal to create an individual’s present internal state, while the outcomes focus on how that present internal state influences appraisal and decision processes that then lead to either thoughtful or impulsive action (DeWall et al., 2011).

Allen and Anderson (2017), applying the GAM, postulates that personal factors and situational input variables may increase or decrease the likelihood of aggressive behavior by influencing a person's present internal state, which includes affect, cognitions, and arousal. In this study, adolescent girls bear personal characteristics or traits that influence how they react to life situations. Even though personal characteristics and traits may be stable across time, situations, or both, the extent to which adolescents may react aggressively may be determined by their context. Thus, the adolescent girls in personality types, especially those in conflict with the law, might predispose them to aggression. Therefore, GAM was considered a practical model that can explain personality determinants of aggression among adolescents in rehabilitation programs in Kenya. Further, the GAM is currently the most common approach used to explain personality in empirical research, which describes personality as a critical variable for understanding personal factors that influence aggressive behavior (Allen and Anderson, 2017).

Current study

Aggression as a variable in a psychological study is an ingrained personality trait. Personality traits are predictors of aggressive behavior in several studies globally (Bettencourt et al., 2006) and other risk factors such as socio-demographic factors. The increasing number of women and girls in aggressive behaviors in Kenya has either led to incarceration or admission to rehabilitation programs. Female offenders currently account for 18 percent of the total prison inmates. In addition, more juvenile jails have been opened in the last 10 years, implying that more young adolescent girls are becoming juvenile female offenders (Mwanza 2020). While several studies attribute aggression to early childhood experiences, age, level of education, parenting factors, and societal influences, there are limited studies in Kenya on how aggressive behaviors influence personality traits (Anderson and Bushman, 2002; Buss and Perry, 1992).

Consequently, this study focused on adolescent girls because several studies show that adolescent males are more likely to outnumber the females in aggression measures (Arnull and Eagle, 2009; Bettencourt and Millier 1996; Lansford et al., 2012; Steffensmeier et al., 2005; Underwood et al., (2009). The study aimed to establish the relationship between personality traits and aggressive behavior among adolescent girls in rehabilitation. Specifically, the objectives of the study were:

i) To examine the relationship between the personality types and socio-demographic influence on girls’ aggressive behavior in rehabilitation programs in Kenya,

ii) To inquire on relationship between family types and development aggression.

Participants

The target population was the three girls’ rehabilitation centers, and the participants were all the 86 adolescent girls aged 12-17 years (M=14.16; SD=8.5) who were under institutionalized care for rehabilitation in the three centers.

Data collection instruments and procedures

The Aggression Questionnaire (A.Q.) by Buss and Perry (1992) was used to measure participants' aggressive behavior. This questionnaire is a 29-item instrument, divided into four subscales; namely: Physical Aggression (nine items) – for example, “If someone hits me, I will hit back”; Verbal Aggression (five items) – for example, “I cannot remain silent when people disagree with me”; Anger (seven items) – for example, “Some of my friends say I am explosive," and Hostility (eight items) – for example, “Sometimes jealousy eats me up inside."

The items in the questionnaire are rated on a five-point Likert scale from 1 (extremely uncharacteristic of me) to 5 (extremely characteristic of me). Andreu et al. (2002) reported a test-retest reliability alpha coefficient for the Aggression Questionnaire (A.Q.) of 0.86 Physical Aggression, 0.77 Anger, 0.68 Verbal Aggression, and .72 Hostility in an adapted Spanish version. In this study, the alpha coefficient of .76 for Physical Aggression, 0.68 for Anger, 0.71 for Verbal Aggression, and 0.78 for Hostility were used in an adapted version. In this study, the tool was translated from English to Kiswahili and back to English. Expert opinion was obtained to ensure content validity. The test-retest reliability alpha coefficient for A.Q. was 0.76 Physical Aggression, 0.69 Anger, 0.71 Verbal Aggression, and 0.79 Hostility compared to the adapted Spanish version. The tool was therefore considered reliable for the study.

The Big Five Inventory (BFI), developed by John et al. (1991), contains five subscales: extraversion, agreeableness, conscientiousness, neuroticism, and openness. The inventory contains a 5 point Likert scale ranging from ''strongly agree" to "strongly disagree." Certain items in the inventory are reverse scored. Some of the sample items from the inventory include "I am talkative," "I am open to new, original ideas," "I cause much admiration in others." In this study, to ensure content validity, the BFI was translated from English to Kiswahili and then back to English, and expert opinion was obtained. To determine the reliability of the inventory, the internal consistency score using test–retest correlations varied between 0.70 and 0.79. The highest correlations were obtained for the scales extraversion between 0.67 and 0.79, neuroticism between 0.68 and 0.72, and conscientiousness 0.66. Openness and agreeableness scores were considered weak at 0.59, 0.60, 0.49, and 0.53, respectively. The socio-demographic questionnaire was used to gather data on the respondents' age, educational attainment, family type, parents' income, and parents' level of education. A reliability Cronbach’s Alpha of 0.76 was determined using test-retest, and the instrument was considered reliable. Data were gathered on a Saturday morning in the rehabilitation centers when the respondents are allowed time to interact with visitors. The respondents presented the questionnaire, and those who could not complete the questionnaire were individually supported. The average time taken by the respondents to complete the questionnaires was 30 minutes.

Data analysis

The data from the questionnaires were first analyzed for descriptive and inferential statistics. Spearman’s correlation coefficient was used to determine the relationship between socio-demographic characteristics and the development of aggressive behavior.

Ethical considerations

The requisite ethical approval to involve adolescent girls was sought and obtained. The Ethical Review Board approval and the research permits from the National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation, and the necessary authorizations from the Prisons Department and the Children’s Services Department were sought and obtained. Data were gathered with the support of qualified psychologists who administered the questionnaires. The girls who were over 18 years signed a consent form to participate in the study. For those who are under the age of 18, consent was provided by the accessible parents and commanding prison officers.

Objective 1: Socio-demographic determinants of girls’ aggressive behavior

Level of education

The results revealed that 82% of the girls (n=70) in rehabilitation centers had only attained some primary school education, 9 (11%) had secondary school qualifications, and 6 (7%) had either no formal education or vocational education. The result implies that most girls were primary school dropouts, suggesting a significant relationship between the girl's levels of education and aggressive behaviors.

Personality types

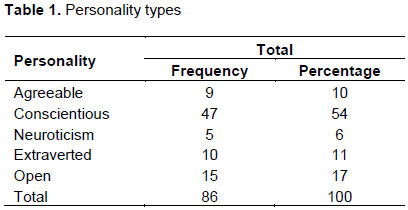

As noted in Table 1, study results reveal that majority of the respondents (54%) were conscientious personality types, with the open, extraverted, agreeable, and Neuroticism accounting for 17, 11, 10, and 6%, respectively.

Family types

The results show that the majority of the girls (46%) were from the nuclear family, 27% were from single mother-led families, 4% were from single father-led families, while 13% were from extended families.

Caregivers’ level of education

Concerning the respondents’ awareness of their caregiver’s education level, results revealed that most caregivers (29%) had attained post-secondary education, 26% had attained primary level education, while 19% had attained secondary level education. In comparison, 21% of the respondents were not aware of their caregiver's education levels.

Caregivers’ sources of income

The respondents were asked to state their caregivers’ source of income. The results reveal that 18% of the caregivers were in employment, 38% in small businesses (kiosks), 19% in large businesses (shops or hardware), while 11% were in farming. Notably, 4% were unemployed, and 10% did casual jobs. The results reveal that 82% of the parents were in informal employment, implying that most were in the low socio-economic bracket.

Reasons for the respondents’ admission to the rehabilitation program

The study sought to find out why the respondents had been admitted for rehabilitation. The results revealed that 8% of the respondents had attempted murder, 45% were involved in drug abuse, 53% were involved in stealing, 41% had absconded school, 19% had escaped from home, 4% were involved in street gambling, while 29% were rescued from the streets. Even though almost all the reasons mentioned above are criminal, they all have a certain degree of aggressive behaviors that predisposed the respondents to risky behaviors.

Aggressive behaviors

The study sought to determine the forms of aggressive behavior that the girls were involved in before the rehabilitation program. The respondents presented a list of aggressive behaviors and then asked to indicate the form of aggression they had manifested. The results revealed that most of the respondents (54%) manifested physical aggression, 46% manifested non-physical aggression, 52% manifested verbal aggression, 48% had non-verbal aggression, 41% anger aggression, while 59% had non-anger aggression. These results show that the respondents experienced and manifested different forms of aggression.

Objective 2: Relationship between family types and adolescent girls’ aggressive behaviors

The study sought to establish the relationship between selected socio-demographic characteristics and personality types and the most prevalent forms of aggressive behaviors, as subsequently discussed.

Family types influence the development of aggressive behavior

The study examined the relationship between family types and aggressive behavior that can lead to rehabilitation. The results show a significant correlation between single-parent and aggressive behaviors leading to rehabilitation (r = 0.064, p<0.05). This implies that respondents brought up in single-parent families are more likely to become aggressive. Further, the results showed that there was also a strong positive correlation between nuclear and extended family and aggression among the respondents (r = 0.448, p<0.05, and r = 0.384, p<0.05, respectively). These results reveal that a specific type of family does not necessarily influence aggressive behavior in adolescents.

Parents’/caregivers' level of education influences the development of aggressive behaviors

There was a weak positive correlation (r = 0.033, p>0.05) between the caregiver’s education level and the forms of aggression manifested by the respondent. However, the relationship was not statistically significant, implying that the caregivers' education level did not influence aggression amongst the respondents.

Parents’/caregivers’ sources of income and aggression

There was a very weak negative correlation (r =-0.021, p>0.5) between the parents’ caregivers’ income source and the forms of aggression manifested by the respondents. The result implied that the income source did not influence the manifestation of any particular form of aggression amongst the respondents. Previous studies have shown that the relationship between parental income and adolescent aggressive behavior is not well- established, and research has produced mixed findings, particularly in adolescent aggressive behavior (Piotrowska et al., 2015).

Personality types as a predictor of aggressive behaviors

Spearman’s correlation analysis was carried out to determine the relationship between the various personality traits and various forms of aggression reported by the respondents.

Extraversion personality trait and aggression

The results show a weak negative nonsignificant association between the respondent's extraversion personality type and physical aggression level (r=-0.051, p>0.05). However, there was a significant positive correlation between extraverted personality type and verbal aggression (r=0.282, p<0.05). Further, there was a significant negative correlation between adolescent’s extraversion and anger aggression (r=-0.254, p<0.05), while there was no significant correlation between extraversion type and hostility aggression (r=0.012, p>0.05) (Table 2). These results are consistent with those reported by Cavalcanti and Pimentel (2016), Bettencourt et al. (2006), and Jones et al. (2011).

Agreeable personality trait and aggression

There was no significant relationship between the respondents in the agreeableness personality type with physical aggression (Table 3) (r=0.001, p>0.05). Further, there was no significant correlation between the agreeableness personality type to verbal aggression (r=-0.105, p>0.05) and hostility aggression (r=-0.085, p>0.05), respectively. These results are similar to those reported by Five et al., (2010), Jovanovic et al., (2011) and Miller et al., (2012), who found no significant correlation between Agreeableness and aggressive behavior.

Conscientiousness personality trait and aggression

The conscientiousness type did not have a significant relationship with physical aggression (r=-0.063, p>0.05); verbal aggression (r=-0.071, p>0.05, hostility aggression level (r=0.133, p>0.05). However, the conscientiousness type was found to significantly negatively correlate with the level of anger aggression (r=-0.233, p<0.05) (Table 4).

Neuroticism personality trait and aggression

Further, there was a significant negative relationship between neuroticism (emotional stability) type and physical aggression (r=-0.257, p<0.05), verbal aggression (r=-0.241, p<0.05); and hostility aggression (r=-0.369, p<0.05) (Table 5).

Openness personality trait and aggression

Similarly, among openness types, there was no significant correlation with physical aggression (r=-0.035, p>0.05), verbal aggression (r=0.043, p>0.05), anger aggression (r=-0.057, p>0.05) and hostility aggression (r=0.018, p>0.05) (Table 6) indicating no relationship between hostility and aggression. These findings differ from those of Bartlett and Anderson (2012), who found a strong relationship between openness aggression, aggressive attitudes, and violent behavior.

The present study examined the relationship between personality types and socio-demographic influence on aggressive behaviors in adolescent girls aged between 12-17 years in rehabilitation programs. Most respondents (54%) had manifested physical and verbal aggression. The respondents manifested a concomitant of aggressive behavior in their social settings and had a high score in physical violence, although they were not necessarily verbally aggressive. Similarly, the respondents who were physically aggressive were also indicated negatively for anger and Hostility. The results are consistent with those reported by Leschied et al. (2000), who found that adolescent girls were more likely to express physical and verbal aggression.

Secondly, this study found no significant relationship between the type of family the girls came from and aggression. The results showed that 46% of the girls had come from nuclear families, which suggests they came from stable families. Even though most studies suggest that aggression is correlated with single-parent families, it is not supported in this study. Vanassche et al. (2014) found that adolescents from single-parent families, stepfamily, or other family types are more prone to aggressive behavior than those from intact families. This study suggests that other factors rather than family types might lead to girls' aggressive behavior.

The results further show that caregivers' level of education was not significantly correlated to girls' aggression. Even though the highest percentage of parents/caregivers had attained secondary and post-secondary education, there was no evidence that there was a link between caregivers' education and aggression in the girls. However, Rahman et al. (2014) noted that caregivers' higher education levels are associated with better psychological outcomes in parenting, thus lowering aggression levels in children. Also, there was no significant relationship between the income source and the aggressive behavior in adolescent girls. Studies that have examined adolescent aggression have reported a small or no significant relationship between socio-economic status and aggressive behavior (Piotrowska et al., 2015).

The correlations between the five personality factors found no significant correlation between extraversion personality traits and physical aggression (r=0.051, p>0.05). However, the extroverted personality trait was significantly correlated to verbal aggression (r = 0.282, p<0.05). There was no significant correlation between agreeableness personality traits and physical aggression (r=0.001, p>0.05), which was similar in other forms of aggression. Similarly, the conscientious personality traits were not significantly correlated to all the forms of aggression. The neuroticism personality traits had a significant negative correlation to physical aggression, verbal aggression, and Hostility. The openness personality traits had no significant correlation with all the forms of aggression. These results are a mixed bag, with some being consistent with previous findings and others not. For instance, Barlett and Anderson (2012) had found indirect effects of openness on aggressive behavior. Cavalcanti and Pimentel (2016) further found direct effects of neuroticism extraversion and Agreeableness in physical aggression, which was not found in this study. Further, Escortel et al. (2020) indicated that the extraversion trait had been an explanatory factor in cyber bullying victims.

However, in this study, it was directly correlated to verbal aggression. Based on the findings of this study, while the Big 5 traits can explain aggressive behavior, some types will be linked directly to a form of aggression while others will be linked indirectly. This is supported by Barlett and Anderson (2012), who argue that Openness and Agreeableness types are both directly and indirectly, related to physical aggression, while Neuroticism is indirectly related to physical aggression, though not too violent behavior.

Some of the limitations of the present study include: The number of girls in the rehabilitation centers might not be a true reflection of all the cases of aggressive behaviors being experienced in Kenya. Furthermore, the girls' level of education in rehabilitation suggests that most of the girls were school dropouts. Therefore, some sections were translated to Kiswahili, which might have altered the understanding of aggression.

This study used the Big Five framework to examine aggression in adolescents engaged in violence, a subtype of aggression. Even though there is a general belief that personality traits account for individuals' reactions to situations, examining how this applies to juvenile delinquency in Kenya might help in developing intervention programs that are informed by personality and aggressive behavior profiling.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

|

Allen JJ, Anderson CA (2017). General aggression model. The international encyclopedia of media effects 29:1-5.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Anderson CA, Bushman JB (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology 53:27-51.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Anderson CA, Huesmann LR (2003). Human aggression: A social-cognitive view. The Sage Handbook of Social Psychology pp. 259-287.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Andreu JM, Pen?a ME, Gran?a JL (2002). Adaptacio?n psicome?trica de la versio?n espan?ola del Cuestionario de Agresio?n [Psychometric adaptation of the Spanish version of the Aggression Questionnaire]. Psicothema 14(2):476-482.

|

|

|

|

|

Arnull E, Eagle S (2009). Girls and offending- patterns, perceptions, and interventions. London: Youth Justice Board for England and Wales, Home Office.

|

|

|

|

|

Bandura A (1978). Social learning theory of aggression. Journal of Communication 28(3):12-29.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Barlett CP, Anderson CA (2012). Direct and indirect relations between the big five personality traits and aggressive and violent behavior. Personality and Individual Differences 52(8):870-875.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bettencourt BA, Miller N (1996). Gender differences in aggression as a function of provocation: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 119(3):422-447.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bettencourt BA, Talley A, Benjamin AJ, Valentine J (2006). Personality and aggressive behavior under provoking and neutral conditions: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 132(5):751-777.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Broidy LM, Nagin DS, Tremblay RE, Bates JE, Brame B, Dodge KA, Fergusson D, Horwood JL, Loeber R, Laird R, Lynam DR (2003). Developmental trajectories of childhood disruptive behaviors and adolescent delinquency: A six site, cross-national study. Developmental Psychology 39(2):222-245.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Buss AH, Perry M (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 63(3):452-9.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bushman BJ, Huesmann LR (2010). Aggression. In: S. T. Fiske, D. T. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), Handbook of social psychology (pp. 833-863). John Wiley

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Cavalcanti JG, Pimentel CM (2016). Personality and aggression: A contribution of the General Aggression Model. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas) 33(3):443-451.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Chen X, Huang X, Chang L, Wang L, Li D (2010). Aggression, social competence, and academic achievement in Chinese children: A 5-year longitudinal study. Development and Psychopathology 22(3):583-592.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Crick NR, Grotpeter JK (1995). Relational aggression, gender, and social-psychological adjustment. Child Development, 66(3):710-722.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Crick NR, Casas JF, Ku HC (1999). Relational and physical forms of peer victimization in preschool. Developmental Psychology 35(2):376-385.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ehrensaft MK, Cohen P (2012). Contribution of family violence to the intergenerational transmission of externalizing behavior. Prevention Science 13(4):370-383.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

DeWall CN, Anderson CA, Bushman BJ (2011). The General Aggression Model: Theoretical extensions to violence. Psychology of Violence 1(3):245.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dishion TJ, McMahon RJ (1998). Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 1(1):61-75.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Dodge K, Price J (1994). On the Relation between Social Information Processing and Socially Competent Behavior in Early School-Aged Children. Child Development 65(5):1385-1397.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Escortel R, Aparisi D, Martinez-Monteagudo M, Delgado B (2020). Personalty traits and aggression as explanatory variables of cyberbullying in Spanish Preadolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(16):5705.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Ferguson CJ, Beaver KM (2009). Natural born killers: The genetic origins of extreme violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior 14(5):286-294.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Fives CJ, Kong G, Fuller JR, DiGiuseppe R (2010). Anger, Aggression, and Irrational Beliefs in Adolescents. Cognitive Therapy and Research 35(3):199-208.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gallo LC, Matthews KA (2003). Understanding the association between socio-economic status and physical health: do negative emotions play a role? Psychological Bulletin 129(1):10-51.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Garnefski N, Okma S (1996). Addiction-risk and aggressive/criminal behavior in adolescence: Influence of family, school, and peers. Journal of Adolescence 19(6):503-152.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Henneberger AK, Varga SM, Moudy A, Tolan PH (2016). Family Functioning and High-Risk Adolescents' Aggressive Behavior: Examining Effects by Ethnicity. Journal of youth and Adolescence 45(1):145-155.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Huesmann LR, Taylor LD (2006). The role of media violence in violent behavior. Annual Review of Public Health 27(1):393-415.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

John OP, Donahue EM, Kentle RL (1991). The Big Five Inventory-Versions 4a and 54. Berkeley: the University of California, Institute of Personality and Social Research.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Jones SE, Miller JD, Lynam DR (2011). Personality, antisocial behavior, and aggression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Criminal Justice, 39(4):329-337.

|

|

|

|

|

Jovanovic D, Lipovac K, Stanojevic P, Stanojevic D (2011). The effects of personality traits on driving-related anger and aggressive behavior in traffic among Serbian drivers. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 14(1):43-53.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Okon MO, Momoh SO, Imhonde HO, Idiakheya EO (2011). Aggressive tendencies among undergraduates: The role of personal and family characteristics. Revista española de orientación y Psicopedagogía. 22(1):3-14.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE (1997). Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies, and guidelines. Annual review of public health 18(1):341-378.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kruti I, Melonashi E (2015). Aggression among Albanian adolescents. International Journal of Academic Research and Reflection 3(6):16-24.

|

|

|

|

|

Lagerspetz KM, Bjorkqvist K, Peltonen T(1988). Is indirect aggression typical of females? Gender differences in aggressiveness in 11-12-year-old children. Aggressive Behavior (14):403-414.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Lansford JE, Skinner AT, Sorbring E, Di Giunta L, Deater-Deckard K, Dodge KA, Malone P S, Oburu P, Pastorelli C, Tapanya S, Tirado LM, Zelli A, Al-Hassan SM, Alampay LP, Bacchini D, Bombi AS, Bornstein MH, Chang L (2012). Boys' and girls' relational and physical aggression in nine countries. Aggressive Behavior 38(4):298-308.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Leschied A, Cummings A, Van Brunschot M, Cunningham A, Saunders A (2000). Female adolescent aggression: A review of the literature and the correlates of aggression (user report No. 2000-04). Ottawa: Solicitor General Canada.

|

|

|

|

|

Liu J, Faan RN, Lewis BG, Evans L (2012). Understanding aggressive behavior across the lifespan. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing 20(2):156-168.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

McGrath PJ, Elgar F (2015). Effects of Socio-economic Status on Behavioral Problems. International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences 2(2).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mejovsek M, Budavonak A, Sucur Z (2000). The Relationship Between Inmates Aggression and Their Socio-economic and Family Characteristics. Croatian Review of Rehabilitation Research 36(1):75-86.

|

|

|

|

|

Miller JD, Zeichner A, Wilson LF (2012). Personality correlates of aggression: evidence from measures of the five-factor model, UPPS model of impulsivity, and BIS/BAS. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27(14):2903-2919.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mwanza MM (2020). Family factors influencing the development of juvenile delinquency among pupils in kabete rehabilitation school in nairobi county, kenya. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal 7(10):531-545.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Nocentini A, Fiorentini G, Di Paola L, Menesini E (2019). Parents, family characteristics and bullying behavior: A systematic review. Aggressive Violent Behavior 45:41-50.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Piotrowska PJ, Stride CB, Croft SE, Rowe R (2015). Socio-economic status and anti-social behavior among children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 35:47-55.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rahman A, Bairagi A, Kumar DB (2014). The Effect of Socioeconomic Status and Gender on Adolescent Anger in Chittagong. IOSR Journal of Humanities and Social Science 19(3):63-68.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Rahman AK, Huq MM (2005). Aggression in adolescent boys and girls as related to socio-economic status and residential background. Journal of Life Earth Science 1(1):5-9.

|

|

|

|

|

Roberts BW, Jackson JJ, Fayard JV, Edmonds G, Meints J (2009). Conscientiousness. In: M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (p. 369-381). The Guilford Press.

|

|

|

|

|

Rodríguez-Naranjo C, Caño A (2016). Family Climate and Adolescent Aggression: An Analysis of their Relationships.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Salmivalli C, Kaukiainen A (2004). Female aggression" revisited: Variable? and person?centered approaches to studying gender differences in different types of aggression. Aggressive Behaviour, 30(2):158-163.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Soto CJ, Kronauer A, Liang JK (2016). Five-factor model of personality. In S. K. Whitbourne (Eds.), Encyclopedia of adulthood and aging (Vol. 2, pp. 506-510). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

|

|

|

|

|

Steffensmeier D, Schwartz J, Zhong H, Ackerman J (2005). An assessment of recent trends in girls' violence diverse longitudinal sources: is the gender gap closing. Criminology 43(2):355-406.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Underwood MK, Beron K, Rosen LH (2009). Continuity and change in social and physical aggression from middle childhood through early adolescence. Aggressive Behavior 35(5):375-373.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Vanassche S, Sodermans AK, Matthijs K, Swicegood G (2014). The Effects of Family Type, Family Relationships, and Parental Role Models on Delinquency and Alcohol Use Among Flemish Adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies 23:128-143.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Viale-Val G, Sylvester C (1993). Female delinquency. In: M. Sugar (Ed.), Female Adolescent Development (2nded.). New York: Brunner/Mazel, Inc.

|

|

|

|

|

Yizhen Y, Junxia S, Yan H, Jun W (2006). Relationship between family characteristics and aggressive behaviors of children and adolescents. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology [Medical Sciences] 26(3):380-383.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Zirpoli TJ (2008). Behavior Management: Applications for Teachers, 5th eds. New Jersey: Pearson/Merrill Prentice Hall.

|

|