ABSTRACT

Adera childcare is a community-based kinship type of care arrangement that has been practiced in many parts of Ethiopia for years. Research evidences indicate that this practice avails alternative care and support that make important contribution in the life and development of children. However, some evidences also indicate that there are concerns and challenges that would compromise the quality and contribution of care particularly compared to experiences of the intact family care. Hence, there is a need to explore the family dynamics that is at work in households hosting both Adera and biological children together. This study attempted to examine this dynamics beginning from the time the children were inducted into the new home. A total of 36 Adera children, a corresponding 36 biological children and 9 parents were selected as participants of the research. While questionnaire was administered to the children to solicit opinions about their relationship with parents and their siblings, interview was held with parents regarding the behavior of Adera children, their treatment of the Adera children and their own biological children. Extended case narratives were also captured from two former Adera children (now Adults) to enrich the data obtained through interview. Findings generally indicated that the Adera care arrangement cannot be viewed as a unitary practice, having uniform arrangements, making similar kinds of provisions, and with only one type (positive or negative) of outcome across the board. Rather, it is multifaceted in practice and impacts; in our present case suggesting both encouraging as well as discouraging results when read respectively from parents’ and children’s perspectives. Hence, its arrangement needs to be participatory enough to involve all the stakeholders (parents, biological children, and the Adera children) at the time the Adera family is to be established rather than making the Adera arrangement only with one of the parents as it has been culturally practiced.

Key words: Adera, community-based care, kinship care, alternative childcare, orphaned and vulnerable children, family-based care.

The Convention on the Rights of the Child recognizes that children have the best chance of developing their full potential in a family environment (cited in Roby, 2011) because the family context avails interaction, first and foremost, with the immediate agents of development and then eventually with agents in the other components of the environment (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). The family is the child’s early microsystem for initial learning about the

world and for learning how to live (Swick, 2004). It offers the child a reference point of the world (Rogoff, 2003), a nurturing centerpiece or else a haunting set of memories of one’s earliest encounters with violence (Rogoff, 2003). The real power in this initial set of interrelations with family is what children experience in terms of developing trust and mutuality with their significant people (Brazelton and Greenspan, 2000; Pipher, 1996). This trusting experience, also called attachment (Bowlby, 1969), is something children and parents or caregivers co-create in an ongoing reciprocal relationship (Bowlby, 1969).

The attachment experience should not in real sense entail that the family set up is reducible into a dyadic relationship. Bowen’s family systems theory (Bowen, 1971) rather views the family as an emotional unit with complex interactions that require a multilevel analysis using systems thinking. It is the nature of a family that its members are intensely connected emotionally. Often people feel distant or disconnected from their families, but this is more feeling than fact. Family members so profoundly affect each other's thoughts, feelings, and actions that it often seems as if people are living under the same "emotional skin." People solicit each other's attention, approval, and support and react to each other's needs, expectations, and distress. The connectedness and reactivity make the functioning of family members interdependent. A change in one person's functioning is predictably followed by reciprocal changes in the functioning of others (Kerr and Bowen, 1988).

An important part of this dynamics that is often overlooked in family reconstruction is the interaction among siblings. Research indicates that sibling relationship remains to be the most long-lasting and influential relationship of a person’s life (Buhrmester, 1992) as it provides physical and emotional contact at critical life stages and often outlasts relationships with both parents and peers (Buhrmester, 1992). It serves as an important socialization agent by providing a context for development of the foundation for the development of sensitivity, social understanding, care giving, and conflict management (Feinberg and Hetherington, 2001). Siblings can also serve as a unique source of support by acting as confidants and counselors who can provide advice to each other during difficult times (Dunn, 1992). As a close relationship, sibling relationships provides opportunities for building critical aspects of human relationships that include affection/emotional security, companionship, enhancement of worth, intimacy, on the one hand, and reliable alliance (a lasting bond), advice and support, and the opportunity for nurturing another person, on the other Buhrmester (1992).

However, Furman and Buhrmester (1985) and several other investigators indicated that sibling dynamics could take a negative overtone as it embodies power relations, conflicts, and rivalries among the children. This could even be the case in families containing birth and foster children coming from different backgrounds or types of adoptions and negative interaction patterns that result when children have different statuses in their families or special needs that require an inordinate amount of parental attention; create stress for other family members, or both (Buhrmester, 1992). Other dynamics that lead to tensions and strife among siblings and lead to negative interactions include competing for parents’ time and attention; loss of family closeness; difficulties dealing with some siblings’ behavior problems, including having possessions stolen or fear of physical aggression (Furman and Buhrmester, 1985). This sibling (negative or positive) relationship impacts, according to family systems theory, on the relationship between components of the family system (Minuchin, 1988). In fact, the nature of this impact has been least investigated in reconstructed families following parental lose due to HIV/AIDS and war, parental separation and divorce, severe poverty limiting parental capacities to care for their children, and a number of other factors causing family breakup (Roby, 2011).

Recognizing the special place this family dynamics and family care assume in the development of children, a number of governmental and non-governmental organizations are increasingly opting nowadays for reconstructing alternative integrated childcare programs that can provide widened opportunities for the diverse needs of children with threatened or disrupted natural family set up (MoWA, 2009; Save the Children UK, 2007).

One such reconstructed alternative family/kinship-based care that has been built into many cultural practices to care for vulnerable children in Ethiopia is the ‘Adera’ care arrangement (Belay and Belay, 2010); an arrangement in which a child is given Adera to someone so that s/he will literally consider and rear up the child as his/her own. Adera is a common parlance in Amharic conversation particularly when requesting someone to perform certain duties and responsibilities on one’s behalf or requiring someone deliver important messages to others, or bringing from or sending items to someone. Under these conditions, it is common to include words ‘Aderahin’ or ‘Aderashin’ to our requests to add emphasis to messages and ensure observance.

The word is so important that it is also used as a name of persons and Scripturally, it is indicated that the Almighty Lord/ Allah entrusts children for parents to care and raise them in recognition of His Kingdom and Holiness in biblical and Qurani writings. Taking refuge in this scriptural providence, believers transfer their children to another guardian at the brink of their death so that the guardian would take care of the children (Mebrate, 2010). In both Christianity and Islam, the death of an individual is considered to be a passing away of one’s flesh alone; not just the end of life or soul and thus Adera endowed to someone in this world is believed to be accounted for in the spiritual world latter after death. Hence, individual believers taking the responsibilities of caring and supporting the Adera child are believed to receive the outcomes of their care and support at the Doomsday from the Holy Lord/ Allah. Culturally, important values are still attached to Adera as shown in the proverb (አደራ ጥብቅ ሰማዠሩቅ, or Adera tibk semay ruk) which upholds that Adera given to someone is a serious matter to be observed (in Mebrate, 2010). Social labellings of Adera recipients as “Adera Ketach” (አደራ ከታች) to those who respect the Adera responsibility to the end and “Aderawin Yebela” (አደራá‹áŠ• የበላ) to those who failed to do so (Ethiopian Language Academy in Mebrate, 2010) are the social and cultural mechanisms of enforcing discharge of the Adera responsibility properly (Belay and Belay, 2010).

Parental arrangement for an Adera care can be made in a variety of ways but mostly with the presence of a religious leader as a witness so that s/he would make interventions latter on when promises and provisions fall apart. Mostly, Adera is given to elder siblings, grandparents, uncles and aunts, and in rear cases, to neighbors and friends (Mebrate, 2010). The important criteria for choosing Adera receivers are not sex, age, or any other factor. Rather, parents select a person whom they trust most and consider him/her as someone that can be entrusted to take care of their children after they pass away or when they are sick and are in bed (Yigzaw, 2009).

Some studies were conducted to examine the practices, roles, contributions and challenges of the Adera care arrangement in Addis Ababa and Chilga, Gondar (Belay, 2007), Bahir Dar and Debremarkos (Mebrate, 2010), and Alamata (Yigzaw, 2009). Belay and Belay (2010) identified existence of the Adera care as a form of substitute parenting for children with dying parents. This arrangement was mainly kinship-based (involving older children, grandparents, aunts, uncles); but it still involved fictive kinship (neighbors, distant relatives, and other familiar persons) as far as they win the trust of the parents. Interview with the children and guardians indicated that the Adera responsibility was highly observed to the extent that Adera recipients feel obliged to transfer their Adera child to other guardians when they were about to pass away or find oneself unable to shoulder the responsibility because of poverty or sickness; an experience named “Adera for an Adera”, or simply “Adera transference” (Belay and Belay, 2010).

Yigzaw (2009) explored Adera practices in Alamata area and noted that the feelings attached to the Adera responsibility was so intense that it was able to urge guardians retain the child at homestead despite the fact that there were all the reasons for these children to end up joining streets. Mebrate (2010) compared Adera and non- Adera (family-based as well as reconstructed family-based institutional) care arrangements and found that the Adera guardians felt honored to be given the Adera responsibility, invested more efforts meeting the needs of the children, and guided the children to develop desirable behaviors and hence the Adera children were more securely attached, resilient and educationally better than the non-Adera groups.

In fact, a number of challenges were also identified. Firstly, giving children Adera to someone may mean assigning responsibilities to the recipients while liberating non-recipients from moral obligation to provide support to orphaned children (Belay, 2007). Yigzaw (2009) noted, for example, that Adera children received low support from other relatives or acquaintances who did not receive the Adera responsibility of caring for children. It was also noted that the life of the Adera taker changes right after taking the Adera responsibility in different ways. For example, in many child-headed Adera-taking situations, the Adera takers experience an added pressure of rearing up the children (Belay and Belay, 2010); that in a way may create a feeling of guilt and worry on the children.

More importantly, the Adera responsibility could in some cases fail (Yigzaw, 2009) as in, for example, the case of a 12 years old boy (who was given Adera to his uncle) saying “My parents gave me Adera to him so that he can take care of me like his children and also to provide me with opportunities for education. But he did nothing to help me while he was treating his children better. I dropped out of school. He forced me to work more beyond my capacity.

Due to these reasons, I decided to run away from home and I joined street life” Another 14 old years boy also said that he was differently treated from the biological children except for food (cited in Yigzaw, 2009). In the light of these issues, there is a need to further explore the role of Adera in childcare, in order to make it more serviceable.

It needs to be explored further mainly focusing on the dynamics that is fuelled with the induction of the Adera child. Understandably, coming into a new house would mean to an Adera child getting into new people and relationships, new living arrangements and conditions, and new roles and responsibilities . Considering the new place as one’s “sweet home”, the caregivers as parents, the biological children of these parents as siblings and the extended family of the household as one’s relatives needs a lot of adjustment from the Adera child.

In the same way, the family dynamics of the household entertaining the Adera child will most likely experience some kind of change in order to accommodate the new member (that is, the Adera child). Parents of the ‘Adera’ child need to take on the additional responsibility of providing for the Adera child together with their biological children, which in turn affect them economically, socially and so on (Yegzaw, 2009). Because of this, interactions between the Adera child and Adera parents and between the Adera child and biological children might not go as smooth as it should be. Previous researchers mainly focused on the outcomes and little was researched about this family dynamism including parent-child and child-child interactions and attachment that are expected to set in with the induction of the new Adera child in his/her Adera family.

This study attempts to capture this dynamics by examining, first and foremost, the experiences Adera children encounter in their new home and how they cope with the changing environment.Furthermore, it assesses the perceived quality of interaction with parents and siblings, as well as the care and support provided there in. Finally, impacts of the care are examined by comparing self-esteem, social interaction skills and future goal orientation of the two groups of children.

Study design

The study was designed in such a way as to assess the parent – (Adera, biological) child and child- child relationships. The study used cross-sectional survey of family dynamics in selected households making a mixed use of qualitative and quantitative approaches. Beginning with assessment of the experiences that the Adera children face in their new environment and adjustments, the study then attempts to document the similarity and differences of relationships and care and support that parents provide to their Adera and biological children. Finally, it compared self-esteem, social interaction, future life goals and career plans of the Adera children with that of the biological children.

Participants

The study was conducted in households containing Adera children in Shiromeda area of Addis Ababa for various reasons. Firstly, Shiromeda was physically closer and familiar to the researchers. One of the researchers had previous encounters with cases related to the Adera care arrangement while engaged in another community-based project. Furthermore, the practice of Adera childcare and support system is common in and around the study area. The target population of this study was then households in this area that are hosting Adera children as their family member and at the same time have their own biological children. A total of 36 Adera children with ages 10-16 years (Mean=12.75), 36 biological children with ages 10-17 (Mean=13.35) years, and 79 Adera parents were selected as participants. A lengthy procedure of identifying, accessing, and selecting these participants was followed. In the interest of space, details of the procedures can be learned contacting the authors. The major reason why we considered children after the age of 10 is that the Adera care arrangement takes enough time to operate and unfolds its possible impact on the children.

Instruments

Questionnaire and semi-structured interview were used for data collection. The semi-structured interview was designed to be held with parents to collect data issues: background information of parents (6 open- and close-ended items), material (6 items), psychological and emotional support (5 items), ) to the children care and protection (7 items), advice, guidance and discipline measures (7 items), interaction (8 items), parental involvement and responsiveness (4 items) and finally, educational support provided to the children (5 items).

The questionnaire was designed to understand the relationship Adera and biological children had among themselves and with their parents. It was composed of sections that measure demographic characteristics (7 opened items), perceived quality of relationship between children and their parents (21 questions), perceived quality of sibling relationship (13 items), children’s perception of parental care and support (11 items), future goal (8 items), social interaction (4 items), self-esteem (ten items), new experience and coping mechanisms (2 open-ended items to identify new experiences that Adera children encountered after they joined their Adera parents). Items of the questionnaire required a-three-point rating scale (Agree = 3, Sometimes = 2 and Disagree = 1).

Items of the instruments were assembled from review of relevant literature as well as other related previous instruments. To begin with childcare and support, the seven domains (physical, emotional, educational, supervisory, verbal, labor and health) were identified based on the Horwath’s (2007) categorization scheme. Accordingly, a total of 76 items were then pooled based on these different domains and borrowing items from instruments developed earlier for a similar purpose in the Ethiopian setting (Yigzaw, 2009; Mebratu, 2010). Items measuring children’s bonding and attachment behavior were adapted from the standardized three point scale, ‘The Parental Bonding Instrument’, originally developed by Parker ( cited in Herz and Gullone, 1999) to assess adult’s perceptions of their parents’ behaviors and attitudes in their early 16 years of life and later revised by Herz and Gullone (1999) to suit the children. Children’s self-esteem measure was adapted from Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965).

Initially, the instruments were prepared in English and then translated into Amharic. The Amharic and English versions of the instruments were shown to two Applied Linguistics and Developmental Psychology experts for checking equivalence, clarity of expressions, level of difficulty for children, and cultural relevance. Comments given on each item against these criteria were accommodated by rewriting the instruments. Then, these second versions were subjected to a pilot test using three parents for the semi-structured interview and five children for the questionnaire. The feedback obtained from the pilot test was used to discard some items, modify others, and also add a few ones.

The questionnaire was designed to understand the relationship Adera and biological children had among themselves and with their parents. It was composed of sections that measure demographic characteristics (7 opened items), perceived quality of relationship between children and their parents (21 questions), perceived quality of sibling relationship (13 items), children’s perception of parental care and support (11 items), future goal (8 items), social interaction (4 items), self-esteem (ten items), new experience and coping mechanisms (2 open-ended items to identify new experiences that Adera children encountered after they joined their Adera parents). Items of the questionnaire required a-three-point rating scale (Agree = 3, Sometimes = 2 and Disagree = 1).

Items of the instruments were assembled from review of relevant literature as well as other related previous instruments. To begin with childcare and support, the seven domains (physical, emotional, educational, supervisory, verbal, labor and health) were identified based on the Horwath’s (2007) categorization scheme. Accordingly, a total of 76 items were then pooled based on these different domains and borrowing items from instruments developed earlier for a similar purpose in the Ethiopian setting (Yigzaw, 2009; Mebratu, 2010). Items measuring children’s bonding and attachment behavior were adapted from the standardized three point scale, ‘The Parental Bonding Instrument’, originally developed by Parker ( cited in Herz and Gullone, 1999) to assess adult’s perceptions of their parents’ behaviors and attitudes in their early 16 years of life and later revised by Herz and Gullone (1999) to suit the children. Children’s self-esteem measure was adapted from Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, 1965).

Initially, the instruments were prepared in English and then translated into Amharic. The Amharic and English versions of the instruments were shown to two Applied Linguistics and Developmental Psychology experts for checking equivalence, clarity of expressions, level of difficulty for children, and cultural relevance. Comments given on each item against these criteria were accommodated by rewriting the instruments. Then, these second versions were subjected to a pilot test using three parents for the semi-structured interview and five children for the questionnaire. The feedback obtained from the pilot test was used to discard some items, modify others, and also add a few ones.

Case narratives

This was a third source of data that was generated during interviews. In fact, it was used as a special form of interviewing in which participants were asked to reflect on experiences in retrospect. Talking about the merits of Adera parenting, some interviewees mentioned examples of individuals who went through this kind of care arrangement and then succeeded in life. There were two such individuals mentioned and the researchers took addresses, contacted them, and then arranged a meeting for case narratives after securing oral consent from them. These two persons were adults (women) who went through Adera care arrangement as children and shared their stories with delight. The stories covered all the gamut of life as an Adera child. The narratives of the two participants were more or less similar and, hence, the experience of only one of them was quoted in appropriate places throughout the presentation of the findings.

Ethical considerations

Letter of recommendation was secured from the School of Psychology to pursue data collection. Moreover, permission was received from the respective school and NGO administrators to collect data from their subjects. Finally, parents of the children were contacted for their informed consent once the students agreed to participate in the research. Participation was based on oral consent as securing written consent is not commonly practiced in Ethiopia. Pictures were not taken and verbal recording of responses during interviews was made with the consent of the interviewees.

The analysis begun with the descriptive characteristics of children considered in the research. Then attempts were made to compare the mean averages of the two groups of children,on perceived quality of relationship with parents, equality of care and support secured from parents, and quality of sibling relationship through an independent t-test. Then the relationship that Adera children have with their parents and siblings was correlated and tested to see if relationship with one party would jeopardize or enhance relationship with another.

Finally, the impacts of Adera care arrangement on the present conditions and future life goals were examined employing one-sample mean test. The impacts were compared between the two groups of children through an independent t- test of means. Qualitative data obtained through interviewing and case narratives were thematically organized and presented verbatim under relevant subheadings and objectives.

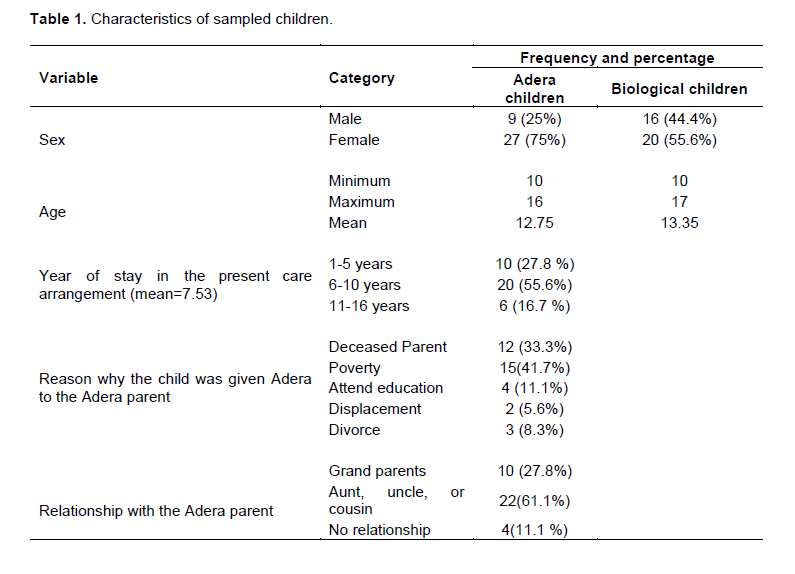

Characteristics of the participants

Participants were grouped into three categories: Adera children, biological children and Adera parents. From the 36 Adera children 9 (25%) were boys and the rest 27 (75%) were girls age 10- 16 years. The biological children were 10 to 20 years; 16(44.4%) were boys while 20(55.6%) were girls. In addition, nine Adera parents were interviewed in the study.

Table 1 shows that 10 (27.8%) of the Adera children stayed for one to five years in the present Adera care arrangement, 20 (55.6 %) for six to ten years, and the rest 6 (16.7%) lived for 11 to 16 years; the mean average of stay being 7.53 years. The reasons for getting into an Adera care arrangement were diverse: for 12 (33.3%) of them it was because both or one of their biological parts were deceased, for 15(41.7%) it was poverty, 4 (11.1%) of them needed to secure better educational opportunities, 2 (5.6%) were displaced, and the rest 3 (8.3%) had divorced parents. As it was also noted in previous research, the majority of the children were given Adera to relatives: 10 (27.8%) were living with their grandparents and 22(61.1%) were living with their aunt or uncle. Only 4 (11.1 %) were living with non-relative guardians (neighbors and distant relatives).

New experiences of the Adera children in their Adera family

Adera children were asked to explain new experiences encountered in their Adera parents’ home Their responses and support seem to suggest that there are in fact differences:

I believe that if my biological parents were there to care for us, they would offer the same thing to me that they to my sister or brother. But, the Adera parents don’t do the same thing for me that they do to their children . I used to get better care and protection, but now it’s not that much. I don’t get as much clothes or educational materials as I used to from my parents.

It was good for my education when I was living with my parents. Once my father died and I came to Addis Ababa to live with my aunt (Adera parent), I am not so happy because she doesn’t take care of me like my parents.

I don’t really give as much attention as I used to for my education because I have too much work load in my Adera parents’ home.

Though a rural life, I used to be happy and it was much comfortable living with my parents. It’s not like that here.

What we can see from the above responses is that some Adera children get less love and attention than they get from their biological parents and they are not happy with their new Adera life. Adera children were not provided equal treatment as the biological children. Some also get less material support like clothing and educational equipment than they used to get from their biological parents. Others had much workload that hindered them from giving enough attention to their education. The case narratives constructed from a former Adera child presents a gloomy scenario in which all kinds of deprivations and mistreatments can happen in an extreme fashion (please refer to this narrative that is presented near to the end of this results section).

With these experiences, Adera children may not be expected to have satisfaction in life,

“I used to be so happy, but now I am not,” “I don’t see my mother anymore,” “I used to be happy”…

Adera children explained what they did to cope with their new experiences. Their reported coping included mechanisms like the following:

I try to adapt myself to a lot of things

I have to be patient

I try to ease her anger so that she would consider me as her child

I do nothing

I have gotten used to it

I try to improve my conduct

I just live through it

I encourage myself

I try to forget about my family,

I try not to grimace whenever they hit me or say rude things and live with patience,

I eencourage myself, become patient, get along with people and know their behavior

I like to talk with good emotion…

I try to work hard and secure good result so that they can accept me

In many cases, children seem to use different coping mechanism together to deal with different members of the family rather than using one coping to all kinds of family problems. These coping mechanisms still change overtime. The narratives of Adera life of a former child presented towards the end of this results section clearly capture the dynamics of this coping scenario.Despite the multifaceted nature of the coping mechanisms, it seems that these coping skills must have successfully worked out to enable the children manage feelings, adjust and continue to live with the Adera family and continue because parental perceptions of their Adera children’s behaviors are strikingly positive. Parental perceptions of their Adera children’s behaviors, feelings, adjustments seem to indicate that the children seemed to use coping mechanism that helps to win parental sympathy and attitudes but not necessarily building resilience:

She opens the TV, picks up food herself and eats when my elder son is not around; but if he is around, she doesn’t do this; she goes to her bedroom and stay there because they aren’t in good terms (04).

She doesn’t ask for food, doesn’t touch the TV set unless we open it. She pleases me; happily does whatever she is instructed. My children discuss among themselves; but my Adera child is rather closer to me. She never troubles me; I personally check materials she needs and buys for her; she doesn’t ask for such things. I have a special pity for her and mouth her food hiding my children so that they mayn’t feel sad noting this partiality. Her behavior is much better than my own children (13).

Sometimes she does not feel comfort; not relaxed. She doesn’t feel at ease. She feels that she misses her family. She doesn’t ask for food herself; I have to give her myself. She watches TV only when other children open the TV set; she doesn’t do it herself. She is the only one who tries hard to please me; asks what I want her to do before I give her

instruction. It is my children who ask me buy them what they see their friends having; but she doesn’t trouble at all. She feels sad when quarrels with others. She easily frustrates, feels bad (30).

He is just like other children of mine; no difference. He doesn’t ask anything about his former family. Asks for anything, food personally; opens the TV set anytime h wants to watch… (31).

He is like other children of mine. He doesn’t remember; talk about his former family. He considers us as his own family. He behaves as he likes; asks for anything he needs, food; opens and closes the TV set himself as he wishes (35).

He considers hmself as my son. He came young at 4 years and doesn’t remember anything else. He openly asks for food or anything he needs. He opens the TV set himself (21).

Other children don’t like to be mouthed their food; my Adera child likes and I do mouth. He considers me as my son. He doesn’t remember anything about the past. He does things by himself including opening the TV set (25).

Some Adera children show positive attitude to their new experience while others respond that there is no difference from their biological parents’ home and care. The participants who indicated that there is no change of experience were those who joined the Adera family at an early age and do not remember their biological parents’ home or care.For those other children to whom their new experiences are said to be better than life with biological parents, reference was made to having access to television, being freed from herding animals and going to school as new and positive experiences. These are children from rural areas where there are lots of hardships and deprivations in the country side. Such responses that show positive experience of Adera children in their new home included the following:

I used to be bored, but now that I am living with my grandparents I am so happy. We have a large compound and a wide screen TV.

I have experienced a lot of difference; it has helped me to give more attention to my education. So there is a lot of change.

I used to herd sheep, now I don’t; there was no TV or satellite dish, now we have both; there was no school, now I can go to school.

I don’t know the difference because I have never lived with my parents.

I was not happy when I first came until I get used to it, but now I am happy.

Biological children were also asked to state any difference in their home since the Adera child joined the family. Most responded that there was no difference while some gave the following responses:

She does most of chores that I used to do; there is no other difference.

The attention that I get from my family has decreased after the Adera child has come.

Economic problems

My parents were happy since they thought I was no more alone, but I sometimes feel sad since she shared my parents’ love. Sometimes my mother gives her more attention to make her feel better.

Children’s perception of quality of relationship with their parents

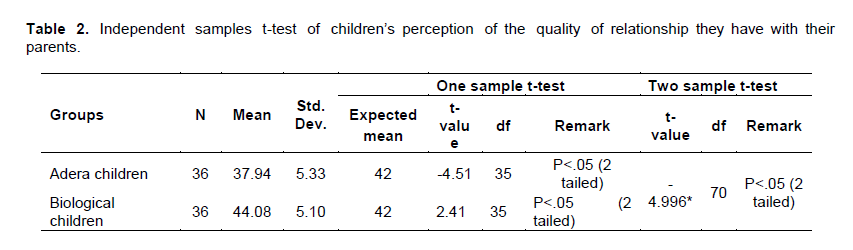

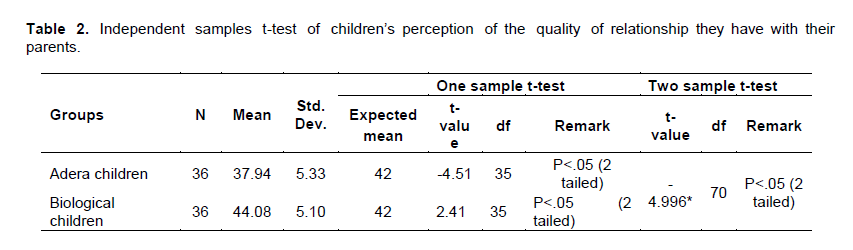

As indicated in Table 2,both biological (M=37.94, SD=5.35) and Adera children (M=44.08, SD=5.10) scored significantly different from the expected mean (n (I) =21, mean = 42). While biological children scored significantly higher (t (35) = -4.51, p < 0.05) than the expected perceived mean ratings of the quality of relationship with their parents, the Adera children rather scored significantly lower than the expected mean (t (35) = 2.41, p < 0.05) .Furthermore, the statistical test revealed that there is a significant difference between the two groups of children in the perception of the quality of parent- child relationship (t (70) = -4.996, p < 0.05).

Additionally, Adera parents were asked to describe their interactions with their Adera children. Some of the questions include ‘’Dose your Adera child share his/her problems with you? Does your Adera child consider him/herself as a

member of the family?’’ The responses of the Adera parents to these questions showed mixed patterns of having both distant and close relationships. Some of the responses were:

There is no secrete between us, she always tells me her problems and worries; I don’t know what she feels inside, but I know she loves me. She always says, “You are my mother I don’t know anyone else” (Interview, Adera parent, female, age 43).

No, he doesn’t have any problems; He doesn’t tell me. He acts like the rest of my children, he plays and fights like them” (Interview, Adera parent, female, age 50).

She does not tell me, she might have discussed her problems with others but not with me; she does not feel comfortable and relaxed like my children; apart from that she considers herself as a member of the family”(Interview, Adera parent, female, age 38).

All of my children including my Adera child tell me what makes them sad or their problems; she tells me that I am the one that she has; she consideres herself as one of my children (Interview, Adera parent, female, age 63).

I do not like secretes. Whatever they are worried about they tell me. I consider my Adera child like my own; he also acts the same (Interview, Adera parent, female, age 51).

My children have no problem; they do not tell me secrete.

They only tell me when they quarrel with each other; they do not tell me about their friends or other things. I consider him as my child he is also like my children (Interview, Adera parent, female, age 40).

They do not tell me their secrets. My Adera child does not tell me, too. I do not understand the way of the young children’s life of this time; I am too old (Interview, Adera parent, female, age 60).

Adera children were also asked to describe their relationship with their Adera parents. Their responses were mixed like the parents:

My relationship with my Adera parents is not like what I had with my biological mum and dad but we have good relationship, they enroll me in school and they are good in the house (Interview, Adera child, male, age 15).

I have very good relationship with my Adera mum; I don’t consider her as my aunt. She is like my real mum. She has been there for me since I was a baby, but my relationship with my Adera dad is not good, we never understood each other (Interview, Adera child, female, age 16).

I consider them like my mum and dad. They also feel like I am their child (Interview, Adera child, male, age 11).

We don’t have a family relationship; they treat me as an outsider like a servant. I think I am only different from a servant because I don’t get any payment (Interview, Adera child, female, age 16).

My Adera parents and children use rude words against me. Sometimes there are disagreements with my Adera parents and their children.There is a lot of difference. For example, I am not happy with my education because I can’t study or do my homework. My aunt (Adera parent) will not be happy if I do because her daughter is not as good as me.

We can also note from the case narrative presented at the end of this results section that the quality of relationshipan Adera child may have with parents may not be monolithic in the sense that the child my differently attune to the Adera mother and father; preferably having better relationship with the parent taking the Adera responsibility. It was the mother who agreed to accept the Adera responsibility in the case of the former Adera child whose narrative we considered here.

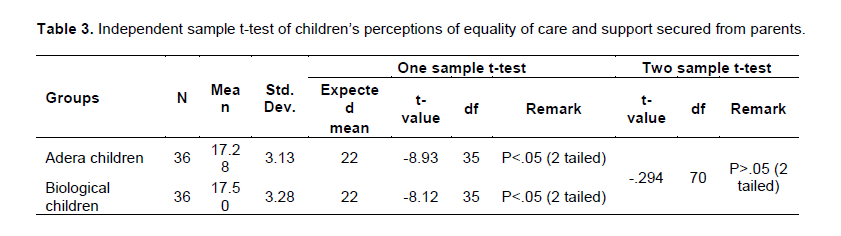

Children’s perception of equality of parental care and support

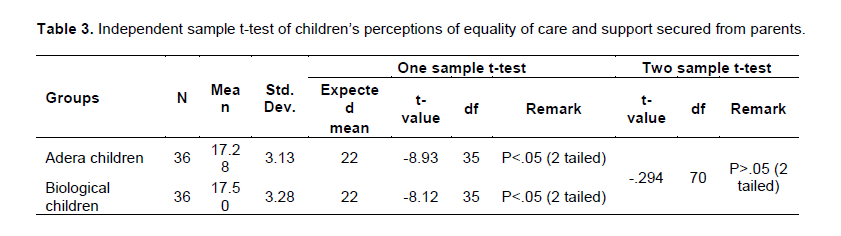

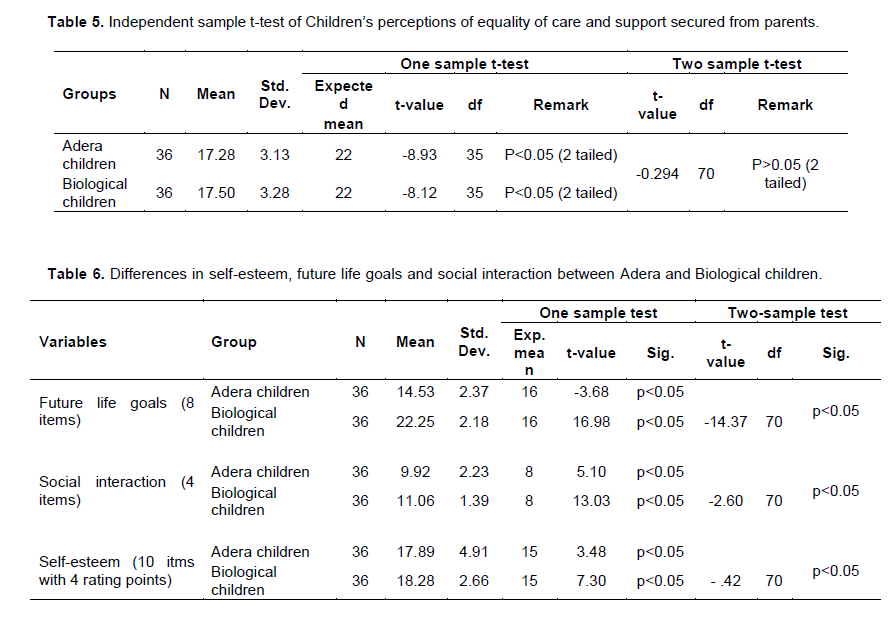

Mean ratings of the perception of quality of care and support received from parents of Adera (M= 17.28, SD= 3.13) and biological children (M= 17.50, SD=3.28) was compared through independent sample t-test (Table 3) and the analysis revealed that there is no significant difference between the two groups (t (70) = -.294, p > 0.05). Ratings of both the Adera (t (35) = -8.93, p < 0.05) and biological (t (35) = -8.12, p < 0.05) children were significantly lower than the expected mean (n (I)=11, Mean=22).Responses of parents regarding care and support they provide for their Adera and biological children seems to corroborate this finding:

My children share beds in twos and threes. My Adera child sleeps on the floor because when he joined our family we did not have any spare space. I have many children of my own, but I try to fulfill the needs of my own children and Adera child (Interview, Adera parent, female, age 53).

My children and my Adera child share bed they sleep in twos; boys together and girls together (Interview, Adera parent, female, age 43).

My older son sleeps alone; he has his own room and bed. My Adera child and one of my own child share bed (Interview, Adera parent, female, age 63).

We all sleep on the floor. All the boys together; my Adera child and the rest of us sleep together. I choose and buy clothes and shoes turn by turn. I go for the needy first (Interview, Adera parent, female, age 51).

Every one of my children including my Adera child has their own bed. I do not choose their clothes; when I buy them I took them with me (Interview, Adera parent, female, age 38).

Adera children were asked to describe the care and support they get from their parents compared with the biological children: positive, negative, no discrimination:

Positive discrimination

Most of the time my Adera mum provides me the same way as her biological children. Sometime there is something that she hides from her older son and do for me like clothes, mobile phone. If he knows what she gets me he will not be happy” (Interview, Adera child, female, age 16).

No discrimination

There is no difference of care and support that we get from our parents. I do not get less or they do not get more. We all get new clothes during holidays (Interview, Adera child, male, age 11).

Negative discrimination

Lots of things are not the same. I do lots of house works but my Adera parent children do nothing ,my aunt (my Adera parent) doesn’t buy me new clothes like her biological children. My aunt sometimes gives me her extra clothes. I don’t eat with them I have to wait until they finish eating (Interview, Adera child, female, age 16).

I do lots of work in the house but not my Adera parent’s children. I don’t ask for the things I need I wait until they provide me with their these needs. But their children ask for whatever they need (Interview, Adera child, male, age 15).

Extent to which negative experiences of sibling interaction could be expressed was captured from the narratives of an adult talking about experiences as an Adera child in retrospect (This is presented without interruption not to disturb reading)…I was very happy; things were quite alright until the little brain of mine started realizing that things around me are not the same as my Adera siblings. I did not have the same sleeping arrangement as others. I sleep on the floor while everyone is on bed; I sat on a carpet when everyone else is on the sofa. I ate after everyone finishes eating and of course I ate a different food that is only made for me and the maids in the house.

I wore clothes that my Adera siblings did not want anymore. As a child, I was not allowed to play with other kids in our area. I had duties rather. I had to deliver milk to customers early in the morning, then clean the house, wash dishes, make coffee, help in the kitchen and on and on. There was something to do; no time to play as a child. These responsibilities remained the same regardless of my school shift, i.e. if I was in the morning shift, all my duties used to wait for me in the afternoon. I never had new clothes for holidays or sing children’s song (i.e. Ababayehosh or New Year’s Song) like the rest of the kids of my age. I hated holidays and I still hate them. Thinking about the past, I now realize that when holidays were coming, I used to get sick; I caught cold if not then a tummy ace. I was in government school and good at school far better than my Adera siblings who went to private schools. My results were good. I used to rank among the top five. I never had time to do home works or study; I merely depended on what I could remember from what was learned in classes. My Adera parents never involved in any of my schooling issues; they did not know how I was doing or which grade I was in to. They never appeared to any of parent teacher meetings or end of year ceremonies. Every teacher of mine used to try to push me to do my home works and study a little better. When they got tired of persuading me to do my home works, they punished me but I never told anyone that I could not have time to do it. They use to consider me as naturally gifted but lazy and carless girl who is wasting her gift (personal narratives, former Adra Child, Female, 30 years old).

I was very close to my Adera mum. She used to listen to what I had to say, knew me better than anyone in the house, protected me from the abuses of her children as much as she could, encouraged me in every direction and helped me to be strong. Most importantly, she believed in me. She always knew I will be somebody in the future and she wanted me to feel like her child. I knew she loves me. She supported me emotionally. My Adera father has never been closer to me but I wanted him to be so. I gave closer attention to his needs and cared a lot about him. I wanted him to be my father; to consider me as his daughter. I even sword on his name for some time until his children told me that he is not my dad and I had no right to swear in his name. So I stopped doing so[1]. After all, he never showed me any compassion or love. He never wanted to know me at all. I was very jealous when I see children with their father on roads. I wished to be one of them...

Perceived quality of sibling relationship

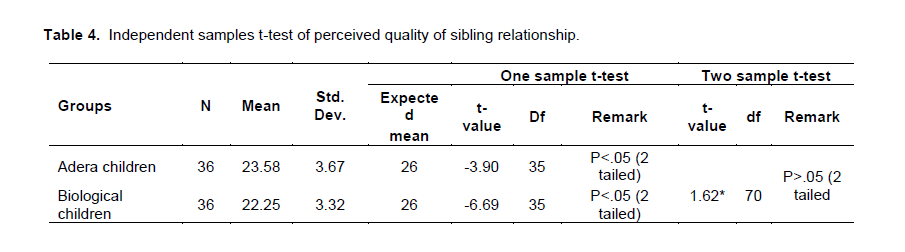

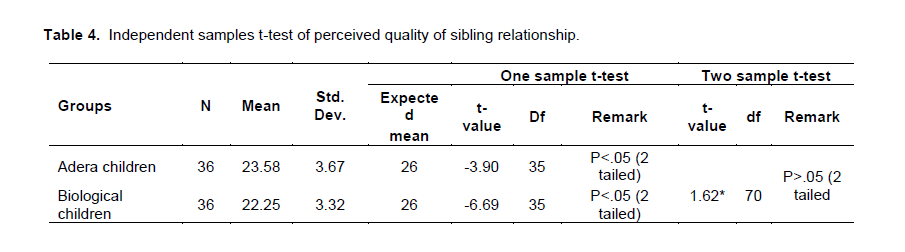

The quality of relationship that the Adera children perceived to have with biological children (M= 22.25, SD=3.32) was significantly lower (t (35)=-3.90, p<.05) than the expected mean (n (I) =13, M= 26.00) and the same was true for the perception of biological children towards the Adera siblings (t (35)=-6.69, p<.05) while in fact the ratings of the two groups were comparable (t (70) = 1.616, p> 0.05) (Table 4). Reactions of some Adera children to their quality of relationship with the biological children were worrisome:

My aunt’s children especially the younger one always insults me and treats me badly. If she sees me studying in the house she will ask me to do things and tell me that I will not be successful (Interview, Adera child, female, age 16).

I don’t get along with my Adera parent’s older child. We always quarrel with silly things; he never wishes good things from me. He doesn’t think good positively me (Interview, Adera child, female, age 16).

This concern seems to take an extremely negative overtone in the narratives of an adult who speaks up her life as an Adera child in retrospect…

I never get along with my Adera siblings. They were bossy and did not want to make me part of their family.They wanted me to know that I am not them by any means, like my skin is dark; my hair is kinky, am not beautiful. I do not deserve to be a child of the house and consider them as brothers and sisters because am not good enough. I did whatever they ask me to do without complain. They never make me feel that I belong to them, never took me to places or family parties, never introduce me to any one as their sister; they said I am someone who is supported by them. They always remind me that I am not one of them so I do not get anything as they have and I need to be thankful to them even for having me. They used to remind me that when they are not around I need to take care of their mother and father and pay back what they had given me because if it was not for them I would have been an orphan. When I was a 9th grade student, I did not have shoes to wear for school. I was wearing slippers that I mended countless times. So my mum wanted to buy me one and she took her youngest daughter with her to shop. I did not sleep since they mentioned of buying me shoes. I had all kind of picture in my mind about the kind of shoes they will buy me but finally they came up with shoes that were not at all meant for a girl; it was police man’s shoes. I was very disappointing and I cried out till my eyes turned red but my Adera sister told me that the shoes was even more than what I deserved. So, I did not have a say in what they gave me. Her words were “you are not a child in this house. Do not expect to have what you want. Don’t consider yourself as one of us because if you consider yourself like one of us you might even want to get inheritance; worse”. Be thankful with what you have. Nobody will do anything for a girl like you. This is more than what you deserve.” I knew then that I have only me for myself but no one else. And I promised to myself that I will make my own money to do that. My only plan was to join university and get a good job. When they find out that I am capable of doing something, they will accept and consider me as one of them”.

When I got to my teen ages, I just went silent in the house. I only talked to my Adera mum. She was my source of information in the house. We talked about almost everything, what she is thinking to do and asked me for my opinion or share me what she have heard, what is going on in the house and about her children but for anyone else in the house I only answered when I was asked to. So, everybody took me as a typical teenager who just ignores everyone. My best friend was myself. I build up another me whom I could talk to, argued and cried with. I preferred to stay with my own self than clinging to someone else. And at that time, all I wanted was to grow up into an adult skipping my teen ages; wanted to be an adult to show them that I can be somebody. I was so sure that they will accept me then.

I loved reading history and fiction books but none was in the house and I was not allowed to go to libraries. Once I managed to borrow one from my school friend. It was a short fiction book. I hid in the barn to read it. I just could not stop reading, time passed without my knowledge and I was late to one of my duties making coffee. They have searched everywhere and found me with my book in the barn and everything went wrong right away. My Adera sister persuaded my Adera parents that I was reading a fiction book because I was in love with someone and my quietness in the house was because of that.

They made it sound like love is not meant for me. Not to love and to be loved. I believed them or I do not know but I was not in to a boyfriend relationship for long. I did not believe anyone who said they love me. Why would I? My own family themselves did not love me so how could a stranger could love me then. And, I always think it is a west of time because I never had a plan of having my own family. My future me is a successful women who is determined in a profession and who spends all her free time with orphans and maybe she will adopt one or two orphans.

My Adolescence was the hardest time of my life. That was the time that I started asking myself and people around me questions like “who I am, whom do I belong to, who cares for me, whom do I care for, why is it hard for my Adera siblings to accept me/ love me, what is my future…? I was very lonely.

I was determined to leave that house by any means and my only plan was to go to one of the universities. But my 12 grade result was not good enough to enroll me to a university; and of course nobody cares about it except myself. I was devastated, depressed and lonely. I had nobody to talk to or asked for help. On top of that, things start to get worse with my Adera father. He started to look at me in a different way than I knew before; I felt like am talking to an outsider. We did not talk much; if we did, we end up with a bad argument. He used to comment in the opposite way to what I meant. We just could not stand each other. A year passed this way and I found out from friends that I could join an evening class at Kotebe Teachers’ College. My Adera mum agreed to pay my school fees. My grades were enough to put me in a diploma program but I did not want to do three years of study. Rather, I joined a two years certificate program so that I could start working a year earlier and get my independence. College was a new beginning for me; nobody knows who I was. I made new friends, all boys of course.

Everyone thinks that I am the happiest girl in the world; one who has no worries and troubles, spends her time watching movies and listening to music, one who has never passed on the trouble and sorrow side of life, who does not know how to cry or to be sad. I managed to make the perfect me that I wanted to show to people. With this experience, I ignored the unhappy me, forgot my past and only planned my future. Nothing has changed with my Adera siblings; they kept on hating me. The first month that I started working, my Adera father wanted me to leave his house. I just gave up. I knew right at that time that I will not get their respect and love by any means. Blood maters and I do not have their blood…

Association between the perceived qualities of relationship between Adera children – parent relationship and sibling relationships

Perception of the relationship between Adera children and parents was far better than relationships with siblings. But, this dynamics may not remain the same throughout the life of the Adera child. An attempt was made to determine if the relationship of Adera parents with the Adera child is independent of the relationship of the Adera child with Adera siblings (Table 7). The correlation analysis in Table 5 has shown, however, that there is a strong impact going from one relationship to the other (r=0.335, p><0.05); attitude of biological children towards the Adera child affecting parental attitudes or vice versa. Although parental attitudes seems better than the biological children, this may not be strong enough to change the attitude of biological children. However, it could be a factor to retain the Adera child continue staying in the family (rather than run away from it) despite all the discontents of life coming from siblings.

Impacts of the Adera care arrangement

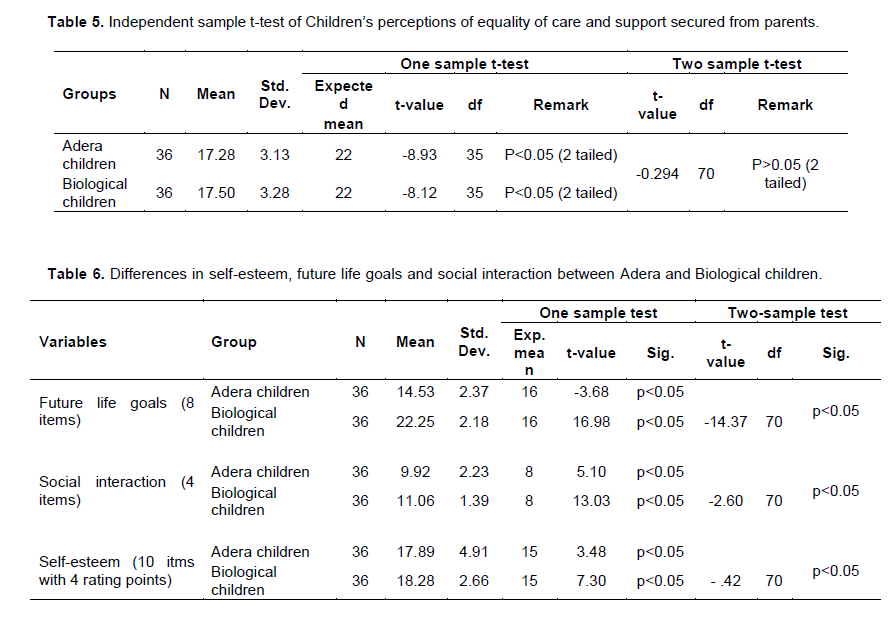

Possible impacts of the Adera care arrangement on the present (self-esteem and social interaction) as well as future life of the children was examined and results of the analysis are displayed in Table 6. As regards self-esteem, mean ratings of the Adera children (M=17.89, SD=4.91) was significantly lower (t (35) = 7.30, p<0.05) than the expected mean (n (I) = 10, Mean=15) and the same was true (t (35) = 3.48, p<0.05) for biological children (M=18.28, SD=2.66). In fact, there was no significant difference in the level of self-esteem between the two groups (t (70) =-0.42, p>0.05).

On the other hand, the biological children (Mean= 22.25, SD= 2.18) had significantly higher mean (t (70) = -14.373, p<.05) than the Adera children (Mean=14.53, SD=2.37). While the Adera children retained a significantly lower future life orientation score (t (35) = -3.675, p<0.05) from the expected mean, the biological children were rather with significantly higher future life orientation score (t (35) = 16.98, p<.05) from the expected mean.

As regards social interaction, there was a significant difference (t (70) = -2.595, p<0.05) between Adera (Mean =9.92, SD =2.23) and biological (M=11.06, SD= 1.39) children such that the Adera children scored significantly lower (t (35) = 5.10, p<.05) than the expected mean (n (I) =8) while the biological children scored significantly higher (t (35) = 13.03, p<0.05) than not only from the Adera children but also from the expected average. Experiences reported retrospectively by one of the two adult participants about their social life as an Adera child would elucidate this point…

I was not allowed to play with friends to go to their home or my friends to come to mine. It was hard for me to explain my family’s situation to my school friends which most of them knew my Adera family. My friends teased me that I was not a biological child. Even if I said it did not matter they came up with all the facts like I did not dress like my Adera siblings, I did not look like them, and my father’s name is different.

It was really hard for me to explain and quite difficult to fit in. I could not handle the teasing and competition of clothes with my girl friends at school so I stopped sitting or playing with girls and my entire friend became boys. Having boys as a friend was a good thing for me they did not want to know me personally, I was not expected to talk about my family or worry about cloth. I just needed to know about movies, music and football. I was considered as a tomboy. I loved

my new identity. To cope up with my boyfriend’s I started to read sport and entertainment newspapers. I did not need to buy them, when I go to deliver milk to shops in the morning I go to the boy who sells the newspapers and he let me read all the newspapers as I can, he sometimes gives me the ones not sold to take them home for free. After sometime, I became the source of news and popular among the boys.

This study attempted to capture how the family dynamics proceeded with the advent of the Adera children in households. As it has also been indicated in previous research (Belay and Belay, 2010), it was noted that the Adera care arrangement was predominantly based on blood ties. It seems that non-blood ties are to be considered only under special conditions as in for example when relatives were not available or don’t meet parental expectations. Unlike findings in previous research, it was in fact noted here that Adera care is not limited to orphaned children but to non-orphans as well. In our present case, in fact, it is only one out of three Adera children that get into this kind of care arrangement because of parental loss. This shows how Adera could serve as a coping mechanism for parents deal with such challenges in child rearing as poverty and related problems.

It has been noted that joining Adera families poses a number of challenges for children. Some of the challenges seem to affect the life of children seriously. Yet, the children managed to stay in the households rather than running away in to other options like starting street life. This has also been shown in previous research where children from Adera families were not found in streets (Yigzaw, 209).

Despite dissatisfactions, unhappiness and a host of feelings of uneasiness, Adera children were able to manage their feelings, adjust to the changing situations and developed coping behaviors that appeared to appease and straighten up the attitude of their parents, if not siblings. Almost all parents were happy with thebehaviors of their Adera children; some even commenting that they are much better than their own biological children.

In fact, children’s perceptions of their Adera parents are not like parents perceiving them. Their perception of quality of relationship with parents is much lower than the expected average and also the average score of biological children. Although Mebrate (2010) indicated that Adera children’s attachment behavior with their guardians was better than the non-adera and institutional children, the finding in our present research is in tune with other previous research on parent-child relationship among mixed family (Henderson and Taylor, 1999) that revealed mothers having more positive relationships with their own (biological) children than with their step-children (included kin children). This finding is still partly supported by UNICEF (2006) about orphans living in kin care arrangement in Zambia that children were experiencing a lack of love and feeling of being excluded from their caregivers.

Perception of care and support was also compared between Adera and biological children yielding that parental provisions were not equal for the two groups as it was also partly noted in Yigzaw’s (2009) FGDs where some Adera children admittedly reported of experiencing less care and support than the biological children. Roby (2011)’s findings from Benin also revealed that fostered orphans and other vulnerable children were often treated differently (e.g. doing extra work and being served less food) than the biological children. Save the Children (2007) also reported that there are significant concerns regarding the potential exploitation, abuse and neglect of children in kinship care, particularly in placements with distant relatives, or when care givers are living in poverty. Experience in India suggests that a child in the care of relatives may not be treated equally with birth children in the same household (e.g. the looked after child is less likely to be given access to schooling).

Findings seem to indicate that much of the challenge in the Adera family’s dynamics seem to relate to the relationship between the two groups of siblings (Adera and biological children). Findings in the present research indicated that the quality of relationship between the two groups of children was perceived by both groups to be lower. Previous research seems to lend support to these experiences; that families containing birth and foster children are likely to generate negative interactions because of background differences that would lead to power assertions and create feelings of competitions and rivalries for parental attention and resources that would make conflicts likely to occur (Steinmetz, 1977; Buhrmester, 1992; Furman and Buhrmester, 1985). Our concern with this family dynamics is that relation-ship patters among members don’t, for good or bad, stand in themselves. Family systems theory (Minuchin, 1988) suggests that the relationship between components of the family system influence relationships within the rest of the family. That is, the parent- child relationship may impact on the sibling relationship and vice versa. As such, if a child perceives themselves as being treated differently to their sibling, this can affect the sibling relationship, particularly if this is considered to be unfair. As discussed by Dunn (1992), research has consistently found that maternal differential treatment correlates with higher levels of conflict and hostility between siblings, particularly during times of stress. Dunn (1992) suggests that this might be linked to siblings competing for parental interest and affection, but it also reflects how relationships within one component of the family system influence those between other family members.

The connection between the parent-child relationships, which is characterized both by the qualities of that relationship and the ways in which the parents manage sibling conflicts and the sibling relationship is bi-directional in nature. This bi-directionality allows the parent- child relationships to impact the sibling relationship, and the sibling relationship to in turn impact the parent-child relationships. Individual aspects of each child (e.g., personality characteristics) have a reciprocal association with both the sibling relationship and the parent- child relationships such that they mutually influence one other (Minuchin, 1988). In this light, the findings of this study proved this to be the case in the sense that the relationship Adera children have with parents and siblings was strong. The other theory that correlates with this finding is family systems theory (Minuchin, 1988) which also suggests that the relationship between components of the family system influence relationships within the rest of the family. Therefore, the parent-child relationship may affect the sibling relationship and vice versa. As such, if children perceive themselves as being treated differently to their sibling, this can affect the sibling relationship, particularly if this is considered unfair. As discussed by Dunn (1992), research has consistently found that maternal differential treatment correlates with higher levels of conflict and hostility between siblings, particularly during times of stress. This might be linked to siblings competing for parental interest and affection.

Researchers found that differences in parenting between one sibling and another has in fact contributed to the non-shared environment and differences in sibling outcomes (Feinberg and Hetherington, 2001). Negative relationship among siblings would also undermine the care and support biological children would give to Adera children. This would mean that children joining the Adera family would get little support to recover from impacts pre-Adera vulnerabilities (eParental loss, impacts of poverty…). In line with this our present findings indicated that Adera children retained significantly lower self-esteem and social interaction skills.Adera children were also found to be less optimistic about their future including establishing their own family and having their own kids. These finding associates with a report by UNICEF (2006) which indicates orphaned children who lived with their kin are less optimistic about their future: they not only expected to have shorter lives but also were less likely to want to be married or to have children.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The main findings of this study included the following:

1. Biological children had better relationship with their parents than the relationship, Adera children had with their Adera parents. The difference between the two groups was also significant. Although findings from other Adera research found that Adera children were securely attached to their Adera parents, this study revealed their relationship was not the same as biological children.

2. The care and support that was provided by parents was not similar to the two groups based on Adera and biological children’s perspective. Interviews with Adera children proved that Adera parents provide less support and care than they do to their biological children.

3. The relationship between Adera and biological children was not strong. Those Adera children who participated in interview also mentioned that their relationship with their Adera siblings was unstable.

4. Adera children who had weak relationship with their Adera parents will most likely have weak relationship with biological children too and vice versa.

5. Biological children’s social interaction and future life goal and career plans were found to be optimistic compared to Adera children. However, self-esteem was not significantly different between these two groups.

The major conclusion is rather that Adera care arrangement is constrained by a host factors, has complex nature and needs to be viewed to have pluralistic feature. Hence, it is a gross error to say it makes positive or negative contributions in monolithic terms. Impacts are multifaceted and dependent on a number of interacting forces. Hence, Adera arrangements by biological parents need to be made in a more participatory manner involving the mother, the father as well as the biological children rather than making it only with one party alone.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Belay T (2007). Raising AIDS orphaned children in Ethiopia: Practices of care and support challenge, and future directions. In Belay Tefera & Abebaw Minaye (Eds.), Caring for orphan and vulnerable children in Ethiopia. Proceedings of the 6th National Conference of the Ethiopian Psychologists" Association. Addis Ababa pp. 60-112.

|

|

|

|

Belay T, Belay H (2010). Orphaned and vulnerable children. India: Gagandeep Publications.

|

|

|

|

Bowen M (1971). Family Therapy and Family Group Therapy. In H. Kaplan and B. Sadok, (Eds), Comprehensive Group Psychotherapy, Baltimore, Williams and Wilkins: pp. 384-421.

|

|

|

|

Bowlby J (1969). Attachment and Loss: Volume 1, Attachment, London: Hogarth Press.

|

|

|

|

Brazelton T, Greenspan S (2000). The irreducible needs of children. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing.

|

|

|

|

Bronfenbrenner U (1979). Ecology of human development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

|

|

|

|

Buhrmester D (1992). The developmental courses of sibling and peer relationships. In: F. Boer & J. Dunn (Eds.), Children's sibling relationships: Developmental and clinical issues.

|

|

|

|

Buhrmester D, Furman W (1990). Perceptions of sibling relationships during middle childhood and adolescence. Child Dev. 61(5):1387-1398.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Furman W, Buhrmester D (1985). Children's perceptions of the qualities of sibling relationships. Child Dev. 56(2):448-461.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Feinberg M, Hetherington EM (2001). Differential parenting as a within-family variable. J. Fam. Psychol. 15(1):22-37.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Henderson SH, Taylor LC (1999). Parent-adolescent relationships in nonstop-, simple step-, and complex stepfamilies. (pp. 79-100). In: E. M. Hetherington, S. H. Henderson, & D. Reiss (Eds.) Adolescent Siblings in Stepfamilies: Family Functioning and Adolescent Adjustment. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 64(4, Serial No. 259).

|

|

|

|

Horwath J (2007). Child neglect: Identification and assessment. New York: Palgrave, Macmillan Publishing.

|

|

|

|

Roby JL (2011). Children in Informal Alternative Care. United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Child Protection Section, New York.

|

|

|

|

Kerr M, Bowen M (1988). Family Evaluation: An Approach Based on Bowen Theory, NY, Norton.

|

|

|

|

Mebrate B (2010). Care and Support of Orphaned Children with Adera, Non-Adera and Institutional Care Arrangements at Debre Markos and Bahir Dar Towns. Unpublished Master"s Thesis, Addis Ababa University, School of Graduate Studies, Addis Ababa.

|

|

|

|

Milewskiâ€Hertlein K (2001) 'The Use of a Socially Constructed Genogram in Clinical Practice', Taylor & Francis Publishers. Am. J. Fam. Ther. 29(1):23â€38.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

MoWA, Ministry of Women's Affairs, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (2009). Alternative childcare guideline on Community-Based Childcare, Reunification and Reintegration Program, Foster Care, Adoption and Institutional Care Service, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

|

|

|

|

Minuchin P (1988). Relationships within the family: A systems perspective on development. In: R. A. Hinde & J. Stevenson-Hinde (Eds.), Relationships within families: Mutual Influences. Oxford: Clarendon. Milewskiâ€Hertlein (2001).

|

|

|

|

Pipher M (1996). The shelter of each other: Rebuilding our families. New York: Ballentine Books.

|

|

|

|

Rogoff B (2003). The cultural nature of human development. New York: Oxford University Press.

|

|

|

|

Rosenberg M (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

|

|

|

|

Save the Children UK (2007). Kinship Care: Providing positive and safe care for children living away from home,' Save the Children UK, Steinmetz SK (1977). The Cycle of Violence: Assertive, aggressive and abusive family interaction, New York: Praeger.

|

|

|

|

Swick K (2004). Empowering parents, families, schools and communities during the early childhood years. Champaign, IL: Stipes.

|

|

|

|

UNICEF (2006). Africa's orphaned and vulnerable generations. New York: UNICEF, UNAIDS & PEPFAR.

|

|

|

|

Yigzaw H (2009). Practice and contributions of Adera in caring and supporting of orphaned and vulnerable children: The case of Alamata Town. Unpublished Master"s Thesis, Addis Ababa University, School of Graduate Studies, Addis Ababa.

|