ABSTRACT

The paper focuses on the role of indigenous knowledge system in the quest for conflict resolution and sustainable peace building. The data were collected from key informants, in-depth interview, focus group discussion, and document analysis. To this end, purposive sampling is used to select the participants. The finding has revealed the existence of many local and community based customary practices and indigenous conflict resolution institutions. Among them is the Amare Council of Elders a well-known and formally recognized mediation and reconciliation mechanism to deal with range of conflicts from simple disputes to horrifying murder acts. There are customary practices and ritual cleansing ceremonies used by Amare in blood feud reconciliation and non-homicide. The prominent ways and modes that have been practiced by Amare conciliators in mediation and blood feud reconciliation include Bele (a kind of swearing to do or not to do something), Arami (a payment from murderer’s family to temporarily calm the issue until Guma will pay) and Guma (blood price during reconciliation). Nevertheless, from transformative peace building perspective, as per the finding currently Amare Shimglina is imperceptible due to the challenges emerged from the community, formal justice actors and conciliators themselves. As a result of these, the paper suggests the need to empowerment and up-keeping of indigenous knowledge systems of conflict resolution for developing comprehensive restorative justice mechanism in the study area.

Key words: Amare, indigenous, conflict resolution, peace building, Jama Woreda.

In the field of conflict resolution and peace building, thorough understanding of the nature, dynamics and context of conflict occurrences should be the fundamental concern. Many contemporary violent conflicts across the world cannot be conceived merely as war but also characterized by a complex host of actors, issues and motives, which exists in extended families, tribes, ethno-linguistic and religious groups. Incidentally, understanding the nature of conflict is imperative to find out the most appropriate and feasible conflict resolution approaches (Mpangala, 2004). According to Zartman (2000), conflict can be prevented and managed in certain occasions but resolved only if parties pursue a compromise and non-zero-sum game results. Therefore, as Bukari (2013) argued, the biggest challenge facing human beings nowadays is not only about the occurrence of conflict per se but also the usage of desired resolution mechanisms. Conflict is an inevitable phenomenon ubiquitous in human society raised from incompatibility and differences of interests, goals and values for resources, ideas, perception, believes, power and status (Swanstrom, 2005; Wanende, 2013).

Indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms refers to the local approach that communities use in resolving localized disputes through historically accumulated and locally defined knowledge, culture, and practices (Murithi, 2006). Regarding to this, Ginty (2008) also argues indigenous mechanisms mean a locally agitated activities, usages, norms and practices used for conflict resolution and peace building. The term indigenous is become interchangeable with many distinctive dispute resolution mechanisms operating outside the scope of the formal justice system. These include customary, traditional, non-state, informal, popular, and alternative methods (Gebreyesus, 2014; Wajkowsha, 2016).

It is true that several societies everywhere have had their own long lived indigenous and customary conflict resolution and transformation methods, which intensely entrenched in the cosmology and cultures’ of the people; however it is hardly found in reality today (Zartman, 2000; Boege, 2006; Omeje, 2008 ). In Africa, the assimilation and imposition of exogenous approaches of conflict in the indigenous one led steady attrition of African traditional values (Bob-Manuel, 2010). Alongside, indigenous approaches to conflict resolution and peace process are endowed with valuable insight for the rebuilding of social trust and restoration of conditions for communal co-existence through more inclusive and community based process since they are inherent and draw from cultural knowledge bases of the society (Lederach,1998; Murithi, 2008).

Apart from this, African indigenous knowledge systems, which practiced for long time through emphasizing on communality and interdependence are rooted in the social, cultural, historical and believe system of the communities (Endalew, 2014). As a result, Africa indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms (ICRMs) inclined on whole community as parties in a dispute through recognizing truth telling, healing, reparation and reconciliation as a major instruments in the lives of African society (Daniel, 2010; Murithi, 2006; Bukari, 2013; Mpangala, 2004; Olateju, 2013). Despite cultural differences and ritual ceremonies in Africa, indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms are holistic, consensus oriented and we-group approach to avoid vicious circle of conflict and they are complementary with the principles of restorative justice (Boege, 2006). On the contrary, Ayittey (2014) argues that the indigenous idiom, which relies on African solution for African problems through African indigenous mechanisms and institutions, has become dishonored. For him it does not mean an intervention of African dictators through corrupt legal system, rather Africans indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms that are deeply rooted in the tradition, custom and values of African society to ensure future peaceful co-existence.

In Ethiopia, which is a museum of diversified ethnic groups, ICRMs have been practiced across different communities for centuries in restoring the broken relationships and ensuring future peaceful coexistence among the conflict parties (Gebreyesus, 2014). In communities of Amhara, its accessibility makes the Shimglina or Council of Elders’ is widely accepted and practiced indigenous conflict resolution mechanism (Bamlak, 2013; Tihut, 2010). As counterpart, Jama Woreda community of South Wollo Zone in Amhara regional state has long lived ICRM called Amare. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to explore the role and process of Amare ICRM in restorative justice and transformative peace building in Jama Woreda.

To effectively address the intended objectives and questions regarding the roles and processes of Amare indigenous knowledge system for conflict resolution, this paper has employed a qualitative research approach. Qualitative approach is preferable for social science research in which it helps to explore, investigate and understand events, theories and human behaviors (Creswell, 2003). To scrutinize useful knowledge in-depth from those who have knowledge about the issue and to acquire insight relationships as well as discover ideas, experience, and interactions and perspectives; exploratory design is advisable (Kothari, 2003). Therefore, taking into accounts the objectives, which needs deep exploration and investigation in its natural setting, this paper is designed to be exploratory. Collecting appropriate data is considerable in context though there are several ways of data collection tools (Kothari, 2003). Accordingly, the researcher conducted 17 in-depth interviewees (with elders, social leaders, religious leaders, Women, Youth), 15 participants in 3 separate focus group discussions with judges and polices, conciliators, and 4 key-informants (from Woreda conflict resolution and security office, culture and tourism office, Militia office and Zone security office). This was to collect the required primary data and make triangulation for data validity and trustworthiness. In addition, document analysis is also employed. To that end, the non-probability sampling technique has been employed in this paper to purposively access the required data from knowledgeable individuals about the issue at hand. Pertaining to this, as Phrasisombath (2009) stated that non-probability sampling technique is preferable in qualitative research to deliberately select the participants of the study.

THE CONTEXT: OVERVIEW OF INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE OF CONFLICT RESOLUTION AND CUSTOMARY PRACTICES

Conflict may be managed by the formal justice system but not resolved and transformed at all because resolution and transformation can be attained through a healing and forgiveness in reconciliation than mere short term managing practices (Zartman, 2000). Customary practices and indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms in Africa are inherited in the culture, norms and customs of the societies (Murithi, 2006). The primordial orientations of indigenous mechanisms and institutions are attached to the disposition and psychology of the specific society. Furthermore, they allowed the parties in conflict to understand that norms and customs have capacities to induce social harmony.

Apart from this, Jama Woreda community has been practicing indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms and customary practices for long. In the community, the customary practices and indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms have religious, psychological and social orientation basements. The presence of such elements in the indigenous mechanisms and customary practices enabled the people to respect the conflict resolution process. The many customary practices and social institutions have aimed to promote and give a sermon to communal co-existence by condemning social evils. These customary practices include idir (social cooperation in time emergency), mahiber (religious association in Orthodox), sedeka (religious association in Islam), debo (social cooperation to do something together), and so forth. Moreover, there are widely accepted and recognized indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms and practices, which have been involving directly in conflict resolution and peace building process in the study area. These include Mesal, Siwur deba (local dispute resolver), Afrsata (way of finding the truth by swear), and Amare (Council of Elders). However, the basic concern of this thesis is examining the place and status of indigenous Amare /council of elders/ mechanism; the researcher would like to understand the other customary practices, which have contributed in the field as follows.

Mesal

Mesal, sometimes called “yeshekoch chilot” in South Wollo (Meron, 2010), is a customary practice and mechanism to investigate the truth for an action done without evidence. Similarly, in Jama community Mesal has been applying at Sheiky house (before Sheiky chilot). With this regard, Sheiky refers to the person who judges or gives Mesal. In this practice, the victim comes and presents the issue to the Skeiky to investigate the truth. Mesal has both material and psychological/spiritual/ dimensions. On the one hand, it is incense (locally called Etan/Adrus/) which threatens the wrongdoer to admit his/her offence before the Skeiky chilot. On the other hand, it has great psychological fear of its consequence if the suspect or wrong doers do not present the truth before the Sheiky. The assumption is that if the wrongdoer fails to admit the truth before the Sheiky, something evil will happen to him or his families. Accordingly, if the wrongdoer does not admit his or her offence, the Sheiky allows the victim to cursing and mooring Mesal against him/her.

Afrsata/Awuchachign/

Afrsata is a community practice in which they meet together to identify the wrongdoers when offences committed at their village. In this case, every resident of the village (from youth to elders) met at a particular place where confessions are usually made. Consequently, if no one admits, all of them must swear. Finally, they curse and blame the unknown wrongdoer in the name of God/Allah via presenting at church or mosque. By doing so, Afrsata is used to avoid social ills and deter the acts of hidden crimes.

Kire/Idir/

Kire is the most prominent and powerful social institution in Jama community. Accordingly, it is people’s contract and customary convection to cooperate with each other in case emergencies. A wise and matured person selected by the residents called Abahaga heads this institution. Kire has regulations and enforcement powers to bind its members of the community. These range from simple warning to social sanctions or isolation. With this regard, during interview with Abahaga, it is reflected that if anyone who is disobedient to that of customary Kire rules, he/she will be punished even up to social isolation. In addition, having a relationship with the one who is sanctioned by Kire is strictly forbidden. Here, if anyone has, he/she also impose punishment as an alliance with wrongdoers. In so doing, Kire has paramount contribution to maintaining social bond and harmony since it is acceptable and binding in the community. As a result, Amare Council of Elders used it in reconciliation process to enforce the conflict parties particularly in serious conflicts and homicide.

Nature and History of Amare Council of Elders Indigenous Conflict Resolution Mechanism

Like many societies and communities in Ethiopia and elsewhere, Jama Woreda community has its own culture of indigenous conflict resolution mechanism. Amare or Council of Elders who are respected and legitimate elders in the community runs this. For long time, in the absence of formally organized justice system people had been resolved from simple to complex conflicts and assured their peaceful relationships through this traditional mechanism. For many generations, village residents were selected representatives of the Council. The primary criteria of selecting these council representatives are age seniority and wisdom to function as Amare conciliators (yehager shimagle, in Amharic). The selected elders were met at a particular place called Beto river-shore under a shadow of a large tree. Beto is a big river where located between Jama and Borena Woredas. Accordingly, Amare Council of elders meets every year to discuss and revise their Kuna (arbitration rules and conventions) to reflect the social changes within the community. Kuna refers Amare Council of elders’ arbitration rules, which govern and mediate cases from simple conflicts to horrify homicides. Later on, the reconciliation place of Amare had shifted from Beto-river to Kebele or villages. This happened because of threats conciliators have faced from the increasing complexity and seriousness of cases, which needs legal protection since Beto located far from villages. Then onwards, Amare Council of Elders is newly organised at Kebele and Woreda levels. Accordingly, Kebele level committee comprises five elders, and seven Amare elders at Woreda level. The Woreda level Amare conciliators are responsible to assist those who work at Kebele to keep the verdict of justice in motion in case of serious and horrible homicide.

Social harmony, relationship and community values are the center of excellence for indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms (Fremont, n.d; Paffenholz, 2003). Likewise, Amare /Council of Elders/ reconciliation system comprised an indigenous knowledge of psychological healing and forgiveness besides material compensation. In addition, Amare is highly focused on preaching pacifism peace thinking that enable the community to develop a peaceful approaches to conflict resolution. This could be through their unreserved efforts of teaching and begging the community to appreciate that blood is never returned by blood, leave hatred and revenge to God and so forth (Elders in FGD3, 24/06/2017). Amare conflict resolution and peace building mechanism has its own ritual practices and different conciliation instruments depending on the severity of cases. Therefore, it has different modes of operations and usages to homicide and non-homicide offences.

Amare’s restorative justice approach to non-homicide conflicts

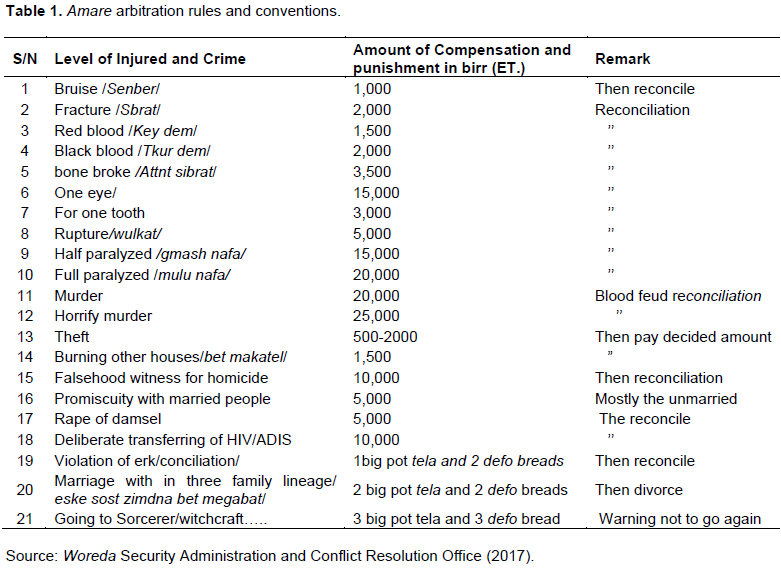

Conflicts and disputes in the study area have varying degrees of intensity ranging from simple family related disagreements to murder. However, the constitution asserts the role of indigenous mechanisms and customary practices to civil and family related issues, Amare Council of Elders has been engaging in criminal matters (Table 1). It has also clear set of compensation amounts and other implicit punishments for each injured and offences.

In addition to these punishments and compensations the perpetrators or wrongdoers should prepare ritual ceremonies like tela (local drink), and Dabo, kolo and ingera (local food) during the reconciliation for parties feed together and induce conciliation. Furthermore, with the degree of victimization, conciliators may also impose labor punishment against the wrongdoers in favor of the victim in the cases of fracture and rapture. Some of these include collecting the victim’s crop (locally, Azmera), collect wood, and buying sheep, and so on. By doing so, sometimes such punishments and practice are subject to critics from economic and human right perspectives.

From economical point of view, preparation of over dozen dabo, kolo and tela are extravagant. Furthermore, forcing the offender to give labor service to victim in addition to the expected compensation imposed by Amare is also against human rights.

Amare’s mode of transformative maneuver in blood feud reconciliation

Homicide has been imposing massive devastating impacts such as displacement of households in Jama Woreda. This is due to culture of revenge in the community. In so far as, it needs the intervention of the culture based indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms alongside the formal justice system. Historically, Amare has played pivotal role in restoration of relationships and transformation of hatred in post-homicide. With this regard, in case perpetrators are under the control of the law in jail, conciliators have played their moral and social responsibility of bargaining between victim and offender’s families to discard culture of revenge (locally, dem melash). This has been doing through blood feud reconciliation (locally called yedem erk) with different customary practices and ritual cleansing ceremonies. Amare conciliators have been doing blood feud reconciliation the perpetrator is either in jail or after his /her release from prison. Most of the time blood feud reconciliation taking place after the release of perpetrators from prison. However, until his/her release vengeance between victim and offender’s families could be prevented through Arami (temporary way of reconciliation to prevent revenge).

Once homicide happens, the perpetrator or his families must request reconciliation with victim’s families through Amare after three months of murder act. The reason for waiting three months is the sign of respect to victim’s families. Accordingly, perpetrator or his family should select three close relative elders from perpetrator’s father and mother pedigree to request conciliators for reconciliation. Consequently, culturally respected and praised Amare conciliators supplicate victim’s family by pacifying that blood should not be paid by blood rather it is better to heal and forgive in the name of God and leave vengeance to God. Until victim’s families consent for reconciliation, Amare conciliators, security persons and religious leaders stay at the victim’s village. After conciliators have consents from victim’s families, blood feud reconciliation process begins with culture based practices and ritual cleansing ceremonies. To that end, there are specific customary rules and ritual practices that have been taking in blood feud reconciliation process for the purpose of compensating victim’s families and avoiding the culture of lineage vengeance as well. These are Bele (swearing), Arami (temporary reconciliation until Guma is paid), and Guma (blood or life price).

A/ Bele

According to participants’ data, Bele has both material and psycho-spiritual dimensions. On the one hand, it is sharp pointed metal called spear (locally, Ankase) and sometimes represented by rifle. On the other hand, it is an oath and swearing taking place at the end of conciliation process to avoid revenge. During reconciliation, Bele (spear or rifle) is seated before the conflict parties and they cross it by swearing if I do not keep my word, Jama Bele will betray me; and if I violate Bele my gun misfire. In so doing, there is a belief in the wider community that once the conflict parties swear/oath/ on bele they can never kill each other and if they attempt, their guns become fail.

B/ Arami

Arami is one of the ways that has been practicing by Amare conciliators to promote social peace when homicide happens. It is a customary practice through which ceremonies held for victim’s and killer’s families to eat together to prevent revenge against perpetrator’s families. Regarding to this, there is a payment by murderer’s families and relatives to victim’s families by denying the perpetrator until Guma is paid for living in tolerance. To that end, the murderer’s families ask consent of victim’s families through Amare elders for Arami. A payment for Arami is varying depending on murderer’s kinship affiliation. Hence, according to Amare arbitration rules each families of the murderer are expected to pay money for Arami independently (father and mother 500 birr, sisters and brothers 100 birr, children and wife 300 birr). The rest of his/her relatives are expected to pay 50 birr. More to this, Muradu and Gebreyesus (2009) stated that in societies of communal life philosophy, murder by individual could be a collective matter. Here, that is why killer’s families and relatives are being responsible to revenge on the one hand, and pay Arami on the other hand in the study area. After Arami is paid, victim’s families swear on Bele not to revenge perpetrator’s families. But if one of victim’s families is not voluntary for Bele, he/she will be punished 1,000 birr and enforce to swear. In addition, if any one of victim’s families is not voluntary to get Bele after Arami is paid, he/she is prohibited or isolated from community based social institutions through social sanction.

C/ Guma

Guma is a blood price that has been practicing exclusively in blood feud reconciliation to reconstruct the post-homicide community. In this regard, Meron (2010) argued that Guma in Oromo community of South Wollo Zone is a way of killing revenge and receiving blood price. In addition, Tamene (2013) also says it is indispensable psychosocial conflict resolution mechanism and a model of restorative justice as a supplement for the state justice system in the Oromo societies. Guma as a life insurance payment by offender or his family (father, mother, brother, sister, child and wife) to the victim’s families so as to avoid linage retaliation currently reaches 20,000-25,000 Ethiopian Birr in the study community.

According to the elders and religious leaders, during the blood feud reconciliation process conflict parties are seat left and right sides. Then after, conciliators hear the stories of both parties in-depth decide the act is either horrified murder or coincidence. Furthermore, the place where murderer and his families will live after Guma is arranged. Accordingly, murderer’s families (father, mother, sisters, brothers, wife and children) should leave to neighboring village (idir) temporarily to reduce the tension with victim’s families. If the market place, plowing land, road and the likes are common areas for the parties, should be clearly demarcated, and prohibited for the perpetrator. It means the killer never attends at the market where common with his enemies instead allowed to go somewhere else.

There is strong and backward thinking of revenge that “blood never gets old; blood return by blood”. To that end, after Guma is paid victim’s families come to swear in bele. If any one of the victim’s families violates the Bele and commits vengeance murder, he/she must pay 50,000 birr and make blood conciliation again. Therefore, conciliators beg the victim’s family to forgive and heal him sincerely in the name of God/Allah. Then after, there are ritual practices and ceremonies to enable conflict parties eat together. To that end, ram goat is slaughter by Sheiky in the name of Bele. If the conflicting parties are from different religions and the slaughter billy goat is one, it must belong to Muslims since the Bele is come from Sheik’s house. Finally, curtain has blank out between victim’s families and murderer, and they exchange give ingera (local food) each other under blank out curtain and the reconciliation process concluded.

Challenges of Amare council of elders in transformative peace building

Although ICRMs in Ethiopia have been doing a lot in restitution of victims and reintegration of offenders to praising social harmony in line with the principle of restorative justice, they faced repression and neglect from the formal legal system (Endalew, 2014). Regarding to this, as elders revealed that the interaction between indigenous institutions and state justice system in the field could determine the visibility of conciliators. Amare conciliators are said to be “Wing of the People” since the community elects them who are respected and have culturally accumulated knowledge. Since elders are familiar with community’s problems, they can provide social justice and harmony. Indeed, council of elders does not focus only direct perpetrators and victims but also all vulnerable groups to maintain social harmony and solidarity. Regarding to this, Meron (2010) stated that in Oromo communities of South Wollo Zone the community would prefer indigenous mechanism to the formal legal system. However, there are factors, which have been hindering the roles of Amare indigenous mechanism in sustainable peace through restorative justice principles and applying indigenous knowledge system. These challenges are classified as community-based, negligence by and inconsistencies with state formal justice system, and conciliators related.

A/ Community-related factors

It is reflected that since the legitimacy and power of customary leaders and Amare Council of Elders originate from the free-will and consent of community, they are acceptable and respected. However, there are social factors emerging from the community and their culture that challenge effective realization of reconciliation. In fact, Amare reconciliation has aspirations and capacities to restore peaceful relationships but problems have been originating from backward attitude of the community.

Accordingly, absence of victim’s or his/her families consent for conciliation is the major problem for Amare’s dis-functionality and discontinuity. This arises from vanity of honor in which if the victim or his families immediately accept conciliation the community considered it as humiliation. One of the elders during discussion clarified the issues as follows:

“There is long lived culture of revenge in our community. If somebody is hurt and bleed, he/she will not reconcile easily unless return similar action. If not, that is considered as a coward and shame in the community. There are many traditional sayings that motivate revenges and killing. Some of these include the man who cannot return his or his family’s blood is coward; blood return by blood /without balanced reaction, reconciliation never sustain. These traditional thinking encourage the victim for revenge and in turn affect reconciliation and peace building process” (Focus Group Discussion, 18/02/2017).

The other community based factor that has been challenging Amare shimglina practice is the repeated violation of Bele /oath/ in the aftermath of conciliation. Bele is recognized conciliator’s instruments in reconciliation and has paramount advantage to reduce the culture of revenge killings. Sometimes parties pretend as seriously reconcile and swear in Bele before Shimagles but they betray and revenge soon.

B/ Negligence by and inconsistencies with formal state justice system: Simplified dichotomy of peace and justice

As justice professionals confirmed that, there are plenty of tasks expected from government and formal justice system to encourage institutions and mechanisms, which contribute for crime prevention and peace building. Besides, this can be done in accordance with their constitutional recognition and acceptance. Sometimes the effectiveness of ICRMs in peace building and conflict resolution is determined and affected by the interest and position of the legal justice system. Accordingly, state legal justice system has posed challenges against the indigenous Amare mechanism either deliberately or negligently.

The first challenge arising from formal justice actors is lack of attention in giving capacity building trainings to elders. With this, regard elders suggested that the state legal justice system considered itself as the sole peace-building actors in the complex community’s social affairs. It means that legal justice actors left aside the indigenous mechanism as too traditional and backward than attempting to empower and make its partner in the peace building area. There is no any capacity building programs and trainings provided to conciliators from the government rather only blaming their unskilled activities. To this end, the absence of consistent and sufficient awareness creation and other related trainings to the community based peace building actors leads conciliators to engaging beyond their scope and mediating all issues exclusively which in turn creates tension with formal justice system.

Absence of favorable work place for Amare shimagles or conciliators is also a challenge that distresses the effective realization of reconciliation. Amare committees reflected that conciliators have no a particular and conducive work place or office to perform their regular tasks. In this regard, amazingly the researcher discussed the Woreda level Amare conciliators under the back of the wall where given to them for working place. This shows the government is giving low attention and left the issue aside negligently but in turn, it implied depluming of the right to use rights (promising facilities) and caused conciliators to lose confidence on themselves and their task. There are also deliberate and conscious intervention of the state justice system in the activities and practices of local Amare shimglina. Accordingly, the lack of legal inclusion to conciliators’ certain reconciliation instrument and decisions create dissatisfaction from the side of Shimagles so far. With this line, Bele and Kire is the basement of Shimagles to enforcing conflict parties and sustaining the reconciliation and peace agreements in more serious conflicts though currently lost their functions. Consequently, elders blame government or legal justice actors as knowingly planning and running against to such cultural values and institutions as backward and illegal. As a result, community based Shimagles become disappointed and uninterested to do their functions. On the contrary, legal professionals’ data confirmed inevitably, the legal system intervene and has not been giving legal support to some of the mechanisms used by elders in the reconciliation process. The reason behind is the nature of such mechanisms run against the formal rule of law since they are consent based not binding in law. By doing so, indigenous actors become incapacitated and consider the intervention as against their power to diminish the peace building effort.

Finally, the politicization of Shimagles (conciliators) for political agenda prior to every day social peace activities also posed challenges to the continuity of Amare’s conflict resolution role. In light of this, the trend of unjustifiable interference in favor of official’s interest is common. In addition, certain officials arbitrarily intervene and attempt to enforce conciliators to change their decisions than giving consistent support.

C/ Conciliators related factors

However, local based customary mechanisms and practices have significant contribution in conflict resolution and sustainable peace building; sometimes they are not congruent to changing circumstance of the modern world. As data of key informants confirmed occasionally Shimagles faced negligence by the state legal justice system and the community as well but these are not the only and underlying factors to downsize the role played by Amare. Rather the lots of personal problems and shortcomings seeming to Amare shimagles or conciliators also in turn diminish visibility of the institution.

In the first place, lack of commitment resulting from absence of payment to Shimagles is a critical challenge. In fact, commercialization of traditional conflict resolution mechanisms is a topical problem and runs against its voluntary nature (Baker, 2013). Elders who are working on conflict resolution are not paid, and give free services so far. With this regard, one of Amare Shimagle remembered “the situation that many years ago when the amount of Guma was 100 tegera Birr they [elders] had 20 of it. But currently, nothing is paid for their reconciliation role rather doing voluntarily for community peace” (Focus Group Discussion with Elders, 18/02/2017). Consequently, this in turn affects their personal life/ household since they spent their work time in reconciliation.

Furthermore, Shimagles’ fear of producing animosity incapacitated the well-functioning of this customary institution practices. Most of the time community considered the role of conciliators as mandatory not as voluntary service. During shimglina conciliators rarely used enforcement mechanisms to the aspiration of perpetuating peace and harmony at parties particularly and in the community at large. However, conflict parties become dissatisfied by decision of elders if the result is disenchanted. As a result, parties produce hatred to elders. In light of this, Galtung (1967) in his transcend approach of theorizing conflict, violence and peace suggested that conflict resolution could create new patterns and goes beyond parties’ goal for future mutual existence. In other words, the goals of parties may not be always kept in reconciliation process but finds the common ground, and if not conciliators may go beyond what the parties want to seek for the aim of ensuring social harmony. Nevertheless, as participants of the research divulged, conciliators and mediators have threat of producing enmity to themselves and their families, which in turn restricts their tasks in the field of peace building.

Conflict continues to be a menace and debilitating for many states across the globe. Apart from this, the scourge of inter-personal conflicts and homicide afflicts the study area of Jama Woreda. As the finding of this study showed, conflict/homicide is a common phenomenon and alarmingly escalating with adverse devastating social and economic effects. These effects are the loss of social capitals and social disorder, household firing and family displacement, economic vulnerability, political mistrust, legacy of psychological trauma, threat and suspicion. The causes of the conflicts have account different sources which arouse in peoples’ interaction and relations deliberately and negligently. Among these are land and inheritance issue, drunkenness and inebriation, corrupt and biased trials in the legal system, illegal proliferation of small arms and the culture of revenge.

Jama Woreda community has many customary practices and ritual ceremonial activities sermonize social harmony. Their indigenous conflict resolution mechanism is called Amare /council of elders/ shimglina. The nature and practice of Amare/council of elders/ as indigenous conflict resolution and reconciliation in Jama community is based on looking at individuals in and from the community to promote social harmony. Amare’s central theme of social harmony and its relationship orientations with the community’s culture of communality fortifies that of reconciliation, forgiveness and healing to be its center of conflict resolution and peace building process. Amare shimglina mechanism has a social and religious basements and responsibilities to mediate and reconcile from simple to blood feud reconciliation. There are customary practices and ritual ceremonies used as instruments in the compensation, mediation and reconciliation process of Amare. These include Bele, Arami, Guma, and other ritual cleansing ceremonies taking at the end of the mediation and reconciliation. These practice have psychological, economic and trauma healing dimensions.

However, the finding of the paper asserts that there are many encountered problems, which undermine the visibility and operationalization of Amare shimglina indigenous mechanisms. These are sourced from the community, negligent and deliberate activities of the formal justice actors and the elders/conciliators/. Thus, the inactive role of indigenous conflict resolution mechanisms and the mere intervention of formal justice in the field are unable to halt the culture of revenge and ensure social harmony.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Ayittey J (2014). African Solution for African Problem:The Real Meaning.

|

|

|

|

Baker B (2013). Where the Formal and Informal Justices Meet: Ethiopians pluralism. African Journal of International Comparative Law 21(2);202-218.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Bamlak Y (2013). Assessment of indigenous conflict resolution systems and practices: implications for socio-economic development. A survey of Simada Woreda, Amhara region, Ethiopia.

|

|

|

|

|

Bob-Manuel I (2000). A cultural approach to conflict transformation: An African traditional experience. Term Paper. Written for the course: "Culture of Peace and Education" taught at the European Peace University Stadtschlaining Austria. Fall Semester 2000.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Boege V (2006). Traditional approaches to conflict transformation - potentials and limits. Berghof Research Center for Constructive Conflict Managements.

View

|

|

|

|

|

Bukari KN (2013). Exploring Indigenous Approaches to Conflict Resolution: The Case of Bawku Conflict in Ghana. Journal of Sociological Research; Macro thinking institute. Volume 4, ISSN 1948-5468.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Creswell J (2003). Qualitative, quantitative and mixed research methodology. 2nd Ed.

|

|

|

|

|

Daniel M (2010). Indigenous legal traditions as a supplement to African traditional justice initiatives. African Journal of Conflict Resolutiosn 10(3).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Endalew L (2014). Ethiopian Customary Dispute Resolution Mechanisms: Forms of Restorative Justice. African Journal of Conflict Resolution 14(1):125-154.

|

|

|

|

|

Fremont J (n.d). Legal pluralism, customary law and human rights in the Francophone African Countries.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Gebreyesus T (2014). Popular Dispute Resolution Mechanisms in Ethiopia: Trends, Opportunities and Challenges. African Journal of Conflict Resolution 14:1.

|

|

|

|

|

Ginty RM (2008). Traditional and Indigenous Approaches to Peacemaking. In: Darby J., Ginty R.M. (eds) Contemporary Peacemaking. Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Kothari CR (2003). Research methodology, methods and techniques. 2nd Ed., New Age International Publisher.

|

|

|

|

|

Lederach JP (1998). Building Peace: Sustainable Reconciliation in Divided Societies. Washington, D.C: United States institute of peace press.

|

|

|

|

|

Meron Z (2010). Shakoch Chilot (the Court of the Sheikhs): A traditional institution of conflict resolution in Oromiya Zone of Amhara Regional State, Ethiopia. African Journal of Conflict Resolution 10(1).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Mpangala GP (2004). Conflict resolution and peace building in Africa as a process: Case Studies of Burundi and the DRC. University of Dares Salaam, the MWALIMU NYERERE foundation.

|

|

|

|

|

Murithi T (2006). African approach to building peace and social solidarity. A senior researcher at the Center of Conflict Resolution, South Africa: University of Cape Town.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Murithi T (2008). African Indigenous and exogenous approaches to peace and conflict resolution: In David JF (Ed). Peace and conflict in Africa. London: Zed book.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Olateju AR (2013). Preserving the traditional measures of conflict in Africa. University of Ibanda, Nigeria: Journal of Education Research and Behavioral Science 2(12):232-238.

|

|

|

|

|

Omeje KC (2008). Understanding conflict resolution in Africa. In David JF (ed.). Peace and conflict in Africa. London: Zed Book.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

|

Paffenholz T (2006). Community Based Bottom-up Peace Building: The Develepment of the Life and Peace Institute Approah to Peace Building and lessons Learned from the Somalia Experience (1990-2000), Sweeden:life and peace institute.

|

|

|

|

|

Phrasisombat K (2009). Sampling size and sampling methods. Faculty of Post-graduate studies and research University of health science practices; USA: University of South Florida.

|

|

|

|

|

Swanstrom NW (2005). Conflict, Conflict Prevention and Conflict Management and beyond: a conceptual exploration. CACI & SRSP, Washington and Uppsala.

|

|

|

|

|

Tamene K (2013). Exploring Guma as an indispensable psycho-social method of conflict resolution and justice administration. African Journal of Conflict Resolution 13(1).

|

|

|

|

|

Tihut A (2010). Gender Relations in Local-Level Dispute Settlement in Ethiopia's Zeghie Peninsula. Human Ecology Review pp. 160-174.

|

|

|

|

|

Wanende EO (2013). Assessing the role of traditional justice systems in resolution of environmental conflicts in Kenya. Centre for Advanced Studies in Environmental Law and Policy (CASELP).

|

|

|

|

|

Wajkowsha E (2016). Doing justice: How informal justice systems can contribute. UNDP, the democratic governance fellowship program; Oslo Governance Center.

|

|

|

|

|

Zartman IW (2000). Traditional curse for modern conflicts: African traditional conflict "medicine". (ed.), Boulder London: Lynne Rinner Publisher Incorporation.

|

|