Full Length Research Paper

ABSTRACT

This article examines the inexorableness of democratic governance in multinational states for sustainable peace by considering the essential questions of the Oromo Protests in Ethiopia from 2014 to 2018. Ethiopia adopted the policy of a 'democratic developmental state' in post-2000, which aimed to realize development initially and then democracy. However, the serious mass struggle was prompted in Ethiopia by the demand for a democratic type of government. And this imperative act became conspicuous in Ethiopia following the outbreak of protest in the Oromia National Regional State in 2014 and resulted in 2018 political changes within the ruling regime. The article was steered as a qualitative research in which both primary and secondary data were utilized. Primary data were collected through interviews and focus group discussions and secondary data were collected from literature through content analysis. Then, Oromo in Ethiopia have been raising the central questions of owning their land for three particular reasons; first, to develop themselves by effectively utilizing available resources, second, to respect human security (not to be displaced from their land, avoid massive human rights violation, and others); thirdly, the questions of self-governance or exercise political power within their territory. These serious questions are pressed on the demand for effective democratization in Ethiopia to reconcile it. Since democratic governance could answer all questions of effective development by averting unequal distribution of resources and averting the threats to human security by amending state-society relationships and it would pave the way to exercise power through democratic election.

Key words: Democratic Governance, Sustainable Peace, Ethiopia, and Oromo Protest.

INTRODUCTION

African states are found in vicious circles of deficiency of development and sustainable peace, which in one way or another is connected with the questions of the democratization process in the continent after independence (Wasara, 2002). Scholars identified the positive relationship between democracy, development, and sustainable peace (Sørensen, 1990). That means the status of democracy directly influences the level of development and security status of a given country. On contrary, following the emergence of China and other Asian countries the relevance of democracy for development and sustainable peace started to be questioned (Chan, 2002) and democracy has been considered secondary to development (Friedman, 1994). In Africa, several issues have been pinpointed as the causes for the worse-off situation of development like; colonialism, corruption, skill gaps, failure in policy orientation, etc. Above all, the political condition in Africa was stated as the bottle-neck to the development and security of the continent (Ake, 1996). The democratization process in Africa was approached in a different context. As described by (Andersen et al., 2007) democratization in some African countries is followed by devastating internal conflict and for others, it starts from the peace-building process (Nizigiyimana, 2015). Similarly, Ethiopia followed peculiar paths in the process of democratizing the country, particularly following the post-1991 political transition (Brietzke, 1995). The post-1991 political setting in Ethiopia was marked by changes from a highly centralized state or strong form of a unitary state to a multinational federal state or decentralized form of government, in which a devolved form of government came into existence (Norman, 2006) in the political history of the country. The political transition in 1991 resulted from serious armed struggle groups. These are; the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) those who defended the colonial thesis in Ethiopian state formation, the Tigray People Liberation Front (TPLF) those who defended the national oppression thesis, and the Eritrean People Liberation Front (EPLF) with the intention of liberation or defense of a colonial thesis (Bach, 2014). And they had their objective of struggle and later through political bargaining they agreed to work together to oust the then military dictatorship (Micheau, 1996) and they established the Transitional Government of Ethiopia with the active involvement of superpowers, particularly the USA through May 1991 London agreement (Lyons, 1996).

In the transitional period, the Eritrean people voted for their independence (Micheau, 1996), and OLF was forced to leave the process. The OPDO replaced OLF to represent the Oromo people, and the process of ousting OLF from the Transitional Government of Ethiopia and replacing it with a puppet organization sowed the seed of serious political animosity between EPRDF and Oromo people. After endorsement of the 1995 FDRE constitution formally, the country was administered by the Ethiopian Peoples Republic Democratic Front (EPRDF) coalition form of government, which constitutes the Tigrian People Liberation Front (TPLF), Oromo peoples' Democratic Organization (OPDO), Amhara National Democratic Movement (ANDM) and Southern Ethiopian Peoples' Democratic Movement (SEPDM) and affiliated with Somali Peoples' Democratic Party (SPDP), Afar National Democratic Party (ANDP), Benishangul-Gumuz peoples' Democratic Party (BGPDP), and Gambela Peoples' Unity Democratic Party (GPUDP) (Lyons, 2011). The post-1991 political transition in Ethiopia came at a time when there were high hopes among Africans, civil society organizations, the international community, and scholars to further the processes of democratization in Ethiopia (Infosheet, 2010). Changing of state structure from a highly centralized unitary form of government to a federal form of state structure was considered a political breakthrough in post-1991. The commencement of the Federal Democratic Republic was politically recognized by diversified ethnic identities and intended to ensure equality among the multi-ethnic group in the country (Abbink, 2010). Besides, the coalition of different political parties under the umbrellas of EPRDF established democratic centralism, in which the executive branch of government plays a decisive role in all political processes and the internally absolute hierarchical network till the village level was established to maintain order at the country and ensure the continuity of EPRDF as a dominant political party in the country. The practice of democratic centralism in Ethiopian politics posed serious challenges in the democratization process and paved the way for approaching federalism without appropriate democratic principles. Then, the absence of appropriate democratic principles created a loophole to build responsible government institutions. Rather, it paved the way for the full politicization of even service sectors and it created tensions between the ruling regime and the citizen. The malfunction of administrative structures and the absence of democracy were articulated as serious threats to stability in the country (Lyons, 2011). Here, the matter of ensuring sustainable peace hanged on how far the government and any state apparatus have been working toward democratizing the state.

Democracy is the most needed principle in the federal form of state structure to realize peace and stability in one country. Thus, some scholars stated Democracy as a moral imperative, in the sense that it represents the permanent aspiration of human beings for freedom, and for better social and political order. And also, democracy was approached as a social process, in the sense that it is a continuous process of promoting equal access to fundamental human rights and civil liberties for all and as a political practice, it's based on the principles of power, sovereignty, rule of law, accountability and perception (Nizigiyimana, 2015). Accordingly, in this study, democratic governance is understood as how a society organizes itself to ensure equality (of opportunity) and equity (of social and economic justice) for all citizens and this factor contributes to the promotion of sustainable peace in the given country (Diamond, 2002). Similarly, sustainable peace is another principal concept in this study. Different scholars forwarded different thoughts on the meanings of sustainable peace and the ways of getting it at the local, national, regional, or international levels. According to the description given by 'International Alert' to the term "peace", it is considered as the functional linkage among individuals, groups, or institutions by the existence of well-governing institutions, equal access to power economy, justice, and feeling safe from other threats and wellbeing (International Alert, 2015). Galtung 1967 further explained the concept of peace as positive and negative peace; in the sense that positive peace mainly lie with the presence of the attitudes, institutions, and structures that create and sustain peaceful societies or far beyond the absence of ferocity while negative peace indicated merely the absence of violence and he pointed out the sustainability of peace is grounded on justices (Webel, 2007).

In Ethiopia, several radical changes in the country different political changes had been introduced in post-1991 to treat the historical burdens of the state formation process through federal arrangements. The government restructured the country in line with ethnic-based federal states to endorse unity in diversity (Lyons, 2008). Federal state structure in any country has to be mindful of political and historical processes and in Ethiopia, establishing a federal state structure is part of answering 1960s questions of nationality and it was anticipated to rectify the processes of failed nation-building projects through assimilation and centralization with the federation. But, whenever federalism attempted to be put into practice without effective democracy, it may result in extreme polarization and test the pace of development and sustainable peace. The perennial nature of social unsteadiness in Ethiopia could be explained by the chief characteristics of the Ethiopian state like; the existence of political exclusion, the issues of the dominance of one over another, and social unrest which was decorated by class, ethnic and regional dimensions (Abbink, 2010). Though, the existence of such upheavals signifies the urgent need for a well-structured and appropriate governance system.

The interface of democratic governance and sustainable peace seems apparent in the sense that, democratic governance should promote sustainable peace, as well as the existence of sustainable peace, should be enhancing the process of building democratic governance as well. Therefore, this interlock of democratic governance and sustainable peace in Ethiopia attested to the highest degree after the outbreak of mass protest in the Oromia National Regional state against the integrated master plan of Addis Ababa in 2014. As a result, Ethiopia faced an unbearable political crisis after the outburst of the Oromo protest. The Integrated Master Plan of Addis Ababa (Finfinne) is presented in different discourses. For instance, for the government it meant to promote the development of the country followed by an integrated regional development plan in 2014; while the opponents (the public) counter-argue by considering the plan as a systematic method of grabbing land from local farmers and it is do nothing with development. Therefore, this article examines the interface of democratic governance and sustainable peace in Ethiopia with special emphasis on protests in the Oromia National Regional state since 2014. Specifically, this article addresses four basic questions: Why protest in Oromia National Regional State? What are the causes of the protest? What are the patterns and consequences of the protest? What makes democratic governance a serious issue in Ethiopia?

MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY

A qualitative research approach was utilized with an explanatory research design to explain the possible relations between democratic governance and sustainable peace in the Ethiopian context. The research employed both primary and secondary data. Primary data are collected through interviews and focus group discussions and secondary data are collected from reports, journal articles, and books. To collect primary data, the researcher purposively selected four zones namely; West Guji, West Arsi, West Shoa, and East Wollega Zones in Oromia regional state conducted twelve interviews with communities and six interviews with the then government officials and also four focus group discussions with purposively selected participants. Conceptually, the research is delimited to describe protest, democratic governance, and sustainable peace in Ethiopia. Geographically, among the then nine regional states and two federal city administrations, the study focused on only Oromia National Regional State. As far as the duration of the study was concerned, the research mainly focused on the political upheavals in Ethiopia from 2014 to 2018. Therefore, the research didn't cover the post-2018 political changes rather it exhibited the preceding context of 2018 political reforms in Ethiopia.

DISCUSSIONS

Overview of Oromo Protest in Ethiopia from 2014-2018

The political questions of Oromo in Ethiopia date back to the late 19th-century resistance against territorial expansion by Abyssinian rules to Southern, Western, and South-Western parts of present Ethiopia. In Oromia National Regional State mass protest started in 2014 after the EPRDF government announced an Integrated Master plan of Addis Ababa with surrounding towns of Oromia National Regional State. The master plan was designed by the Addis Ababa city administration in collaboration with the government of Oromia Regional state and it covers 1.1 million hectares of land (approximately twenty-fold the current size of Addis Ababa); saying that, its implementation will result in the eviction of millions of farmers and families from their land (EHRP, 2016). Ethiopian Human Rights projects of 2016 stated that the anti-integrated Master plan of the Addis Ababa protest was activated in April/May/June 2014 and re-erupted in November 2015. The protest was triggered to oppose the Integrated Master Plan of Addis Ababa with surrounding areas of Oromia National Regional State. Addis Ababa (Finfinnee) is historically, geographically, and politically considered as a core political ecology for Oromo and its epicenter for Oromia. In 1995 the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopian constitution identified two cities located in Oromia, namely; Dire Dawa and Addis Ababa (Finfinnee) as federal cities, and recognized Addis Ababa as the capital city of the country. In 1995 FDRE constitution Article 49 the interface of Oromia and Addis Ababa (Finfinnee) stated five critical issues which confirm the specialties of Addis Ababa to Oromia. The constitution described; first, Addis Ababa shall be the capital city of the Federal State. Secondly, the residents of Addis Ababa shall have a full measure of self-government. Particulars shall be determined by law. Thirdly, the Administration of Addis Ababa shall be responsible to the Federal Government. Fourthly, Residents of Addis Ababa shall under the provisions of this Constitution, be represented in the House of Peoples' Representatives and fifth, the special interest of the State of Oromia in Addis Ababa, regarding the provision of social services or the utilization of natural resources and other similar matters, as well as joint administrative matters arising from the location of Addis Ababa within the State of Oromia, shall be respected. Particulars shall be determined by law (1995 FDRE Constitution). The fifth point of this article clearly stated the special interest of Oromia in Addis Ababa and the location of the capital with the Oromia Regional State. Thus, the 1995 FDRE constitution accelerated the 'special interest' of Oromia in Addis Ababa (Finfinnee) as it is determined by the law and any law formulated in the country does not yet describe the particulars of special interests of Oromia in Addis Ababa (Finfinnee).

The outburst of protest in Oromia Regional State, reported by different international media like; Al Jazeera, The Guardian, Reuters, and The Independent, as a long-term project (for 25 years) of the Ethiopian government to expand the territory of the capital city of the country, (Al Jazeera, 2015; Guardian, 2015; Reuters, 2015; The Independent, 2015), Addis Ababa (Finfinnee) and the master plan was prepared in 2009 and aimed to implement major infrastructure to attract investors in the industrial zone. And, in the sight of the Oromo people the master plan has appeared as a threat to surrounding Oromo farmers for it could lead to the eviction of their homelands and leads to the deterioration of the socio-cultural values of Oromo people in the area. Then, by opposing the negative consequences of the master plan protest was started in different Universities found in the Oromia Regional State and then extended to the grassroots community as a mass protest in 2014 and it was piloted under the hashtag (#OromoProtest#).

Causes and courses of Oromo Protest from 2014-2018

The protest in Oromia National Regional State was mainly triggered by the official launch of the integrated Master Plan of Addis Ababa. But, in social movement studies, there are different causes of conflicts, structural, intermediaries, and triggering causes. In this discourse of protest in the Oromia National Regional state different causes played the paramount role in the escalation of protest in the region. The researcher has discussed with key informants, Focus Group Discussion participants, and interviewees in diverse areas with different parts of communities and government officials and critically analyzed different literature on the issues of protest in Oromia National Regional State and identified structural, immediate, and triggering causes of this protest. The protest in Oromia National Regional State or #Oromoprotest was contextualized differently in different settings among government officials, grassroots communities, and different political parties. The government concluded the causes of this protest as the lack of good governance and external enemies trying to manipulate the internal population, especially the youth. And grassroots communities mainly argue in line with horizontal inequalities and other related factors, while different political parties considered the matter of protest as it emerged from the government policies and they claim ineffective or futile government system in the country.

The research participants in this study area forwarded important points on protests of Oromia National Regional State. The informant of an interview in the East Wollega Zone, Nekemte portrayed the causes of protest in the Oromia regional state as if mainly triggered by the integrated master plan of Addis Ababa that incorporated the Special Zone of Oromia around Addis Ababa (Finfinnee) to the capital city. Also, participant of this study said "… this year we passing through a serious time. Even if it's too difficult for me to tell you the concrete and substantive causes of this protest I know that there is a plan from the federal government what they called the 'Master plan of Addis Ababa (Finfinnee)". From this statement, we can understand how much the protest was considered as serious for the local communities even for those who live in the distant location of the capital city with a sense of nationalism and grassroots communities are critical of government policies, they don't have trust in the system.

In addition, an interview with one elder at East Wallagga Zone of Oromia (Naqamtee) clearly described the demographic changes he observed in Addis Ababa when he narrates his earlier visit to the capital city and the present. He is very much concerned about the displaced Oromo people and the rampant expansion of the city. Respondents emphasized that the integrated master plan of Addis Ababa is the concern of all Oromo people across Oromia because it legalizes the eviction of farmers in their homeland. Besides, the other two key informants explicitly explained their opinion on the causes of this protest from the same study area when popular resistance reached its climax the government tried to appease demonstrators through force and coercive measures government fueled the mass grievance. From this response, the researcher pointed out that, the inappropriate response of the government is another factor that pushes people to continue their struggle. An ironic response from the government would be considered a cause for the second round of protest. Similarly, focus group discussion participants of the same study areas figured out the cause of protest as "the failure of the government system" and they tried to identify these failures of government institutions such as; providing job opportunities or the problem of unemployment, corruption, fail to give right response for the questions of people on time, failed to exercise absolute democracy. Hither, the causes deviated from merely referring to the integrated master plan of Addis Ababa and it touches on the service delivery of the government institutions and the nature of government in the country.

The government officials in this area explained the causes of protest as the deficiency of good governance and external foe of the country. In their arguments, they confirmed the problems of good governance such as; timely response to the questions raised by the community, timely executions of started projects, corruption, and others. In another way, they pointed at some external adversaries that they considered as potential national security threats in general and their specific areas like; OLF and Ginbot in alliance with Egypt and Eretria through social media Facebook, and TV (ESAT and OMN). Their arguments are deemed to be externalizing the internal problem of the country. When we compare it with the argument from the community it sounds different. Because the informant from local communities of the study area didn't say anything as far as external foes and political parties the government officials labeled as national security threats. The key informants of the research from the second site of the (West Shoa Zone; Ambo) of Oromia have explained the causes of protest as stemming from the dated back ineffective government policy that created deprivation among youth due to high levels of unemployment and economic exclusion or unfair resource distribution. The problem of unemployment and corruption was embedded in the government system. The participant stated that "such inadequate government system played a significant role to push people to protest against the system" (emphasis added). Furthermore, the issues of equality and effective utilization of natural resources are described as the factor for protest. Other participants understood as the Oromo protest erupted from triple causes; the effects of the history of the country, the absence of real democratic practices, and the absence of trust between the government and the grassroots community. The government officials on their side confirmed the existing problem of good governance as the major cause of this protest. In addition, they pointed out some internal and external factors that contributed to the escalation of this conflict; "internally like, high rate of unemployment, corruption and the external enemies popularized the internal problems and distort the peace and development of our country".

The respondents from the third site of the study (West Guji Zone; Bule Hora) articulated the causes of protest in line with access to the resource of Oromia Oromo for the benefit of the Oromo people and they expounded on the problem of the government system. In detail to incorporate what has been said by research participants in the area; one of the key informants explained the cause of the protest in Oromia National Regional State in general and West Guji Zone in particular, there has been framed in economic, political, and social aspects of Oromo people. The Participant of the research portrayed how the natural resources in their areas were exploited by others without the benefit of local people and these facts pushed people to protest against the government system. He also described the political factors behind the protest in Oromia National Regional State this participant said that "…Oromo people need real democracy in this country; in which community elect their representatives freely and exercise regional autonomy in presence of real federalism". The argument brought an important point to reflect on the far-reaching hope of democratizing Ethiopia under a federal arrangement. Besides, participants disclosed that the social issues overdue the protest figured out by saying "the current government can't preserve the indigenous governance of Oromo people as it is and there are a lot of interventions of government in the social affairs of Oromo people. For example, during the festival of Irrechaa in 2016 hundreds of people died on a single day, and the government was directly or indirectly involved in the process of the Gadaa system by lobbying Abba Gadaa (the responsible person to exercise power in the Gadaa system) in this area" he said. Though, participants thought the immersion of the government in social affairs mainly the cultural practice of the community in this area considered the issue in the protest in the West Guji zone. Another informant in the West Guji zone elucidated the causes of protest concerning the violation of human rights in the Oromia regional state and labeled the government institutions as the potential perpetrators of human rights and unfair natural resource exploitation in the area. As an example of natural resource exploitation in the area, for instance, 'Gidabo Gidib' displaced around 300 farmers from their lands without enough compensation, Gaara Eebbicha, Okkotee gold mining area was also targeted but not successfully controlled by investors because of people upheavals, Mio Beeki, Maddoo, Adoolaa and Qanxicha, Adoola forest, Baarii forest are handed over to 'EFFORT COMPNAY' (Endowment Fund For Rehabilitation Of Tigray), which owned by Tigray People Liberation Front and they extract resources without considering the sustainability".

On the violation of human rights in Ethiopia, this participant says "…it's difficult to endure the torture, jail and extremely inhuman acts (hanging, fixing bottle filled with water on the male's private part, etc.) on Oromo people; I tell you this from my experience at Makelawi". Another participant in the same said, "Guji people are protesting to ensure their survival". Again, the fourth participant explained the causes of protest as protest erupted because the government failed to provide needed service for the community and the fifth participant considered the causes of protest to change the regime in the country. The government officials in their side explained the causes of protest as the problem of good governance namely; corruption, giving responsibility for the community on time or in other words answering the problems of people, dealing effectively with the issues of natural resources in this area to grantee the interest of indigenous people or local community. In addition, the local government officials also mentioned the problem of an external enemy to insist the youth revolt against the government. The participant from West Arsi Zone (Shashamannee) explained the causes of the protest as mainly referred to the questions of full ownership of Oromia (in Afaan Oromo; gaaffii abbaa biyyummaa uummata Oromo) and in addition, they portrayed the horizontal inequalities among communities in Ethiopia and economic problem in Oromia National Regional State in general and their zone in particular. The government officials of West Arsi Zone considered the causes of the protest in a different dimension. They identified three significant causes of protest in their area; first, they mentioned the problem of radicalism or extremism in their area. They elaborate on the threat of extremism in the West Arsi Zone in which the Oromo Muslim-dominated area they claimed some social contentions they have experienced in past four or five years on religious issues and the upheaval in this area started before the outbreak of protest throughout Oromia by some individuals those who have connections with some individuals in the Arab States and later it was shadowed by the national question about Master plan of Addis Ababa and other questions of Oromo people. In addition, they reflect the problem of good governance as another cause of protest in the area like other areas.

Besides those primary sources of information on the causes of conflict, different secondary data described different causes of protest in the Oromia National Regional State. One critical writer on Oromo affairs Asafa (2016) considered the protest in Oromia National Regional State by saying "this popular movement clearly shows that, the Oromo people are the fulcrum for bringing about a fundamental political transformation in Ethiopia and beyond to establish sustainable peace, development, security, self-determination and egalitarian multinational democracy". His painstaking reflection on the protest in Oromia regional state as anticipated conveys fundamental political transformation in the Horn of Africa.

Besides, Asebe (2016) portrayed the rationale behind of Oromo people to protest against the integrated master plan of Addis Ababa revealing four important arguments; "first, memories and experiences of past evictions and dispossessions; second, response to the constitutional rights mainly Act 43 (2) of FDRE constitution, third, mistrust generated from lack of genuine participation; fourth, anticipated Repercussions on the identity, culture, and livelihood of the Oromo". Hence, the integrated master plan of Addis Ababa knocked into the social, political, and economic aspects of the Oromo people from the past to the present and future. Similarly, Ethiopian Human Rights Project (EHRP) acknowledges the democratic deficiency in the country as the cause of protest in the Oromia National Regional State (EHRP, 2016). As stated above, the government report revealed the problem of good governance in the country and higher government officials confirmed that such public protest emanated from the facts of missing adequate governance.

Patterns and consequences of Oromo Protest Between 2014 - 2018

On the Nature of protest, scholars argue in different ways. Violent protest is when the mass population participated in the courses of protest abstain to take any form of vehement actions and when reflects their needs and aspiration concerning the body and also government recognizes them as peaceful campaigners. Contrary, violent protest is when the mass population accelerated their grievances through violent actions (Garrett, 2006). The participants of the study argue about the nature of the protest as it started nonviolently and ended with violent protest. The participants of FGD in East Wollega Zone argued that "the majority of the people who participated in the demonstration don't have any aspiration to take any violent measures on properties or the government personnel mainly the cabinet, armed forces and other spices/spies of the government but this changed to violent automatically after the armed forces tried to forced people to not demonstrate". Similarly, the in-depth interview participant from Western Shoa on the nature of protest says that "I observed when people demonstrated without taking any action of violence before the armed force intervene but after that course was changed and people started to take violent actions against government security forces with what they have at hand, which is stone". The FGD participants in West Arsi Zone and some key informants in West Guji Zone reflected that "the government take violent measures on nonviolent protest and changed the nature of protest". The government officials in all study areas shared the same views on the nature of the protest and they claimed the demonstration was started without the consent of the government and in its very nature, the protest was violent. Furthermore, the government officials argue on the protest as it happened without legal grantees because the government constitution allows peaceful demonstration but that demonstration was restricted from areas like the markets, around the government officials, and near different religious institutions the demonstration participants tried to demonstrate without considering these and the government intervened peacefully to protect peace and order in their areas.

Generally, the nature of protest in Oromia National Regional State participants of the study revealed that at the beginning the protest went as a nonviolent protest meaning that people accelerated their views through demonstration without participating in any acts of destruction either on the people or properties. Later on, the course changed after the government forces intervene in the ongoing demonstrations and people started to take violent actions and the nature of protest changed to violent protest. The protest in Oromia National Regional State followed different patterns. According to the EHRP report in 2016, the protest was shaped in different rounds. The first round of protests started in April/May/June of 2014 followed by the official announcements of the Integrated Master Plan of Addis Ababa. This round of protest concentrated on educational institutes and students at different levels participating and it was paused after the government officially announced to stop the plan until people have clear consent on the advantage of the project (EHRP, 2016). The second round of protest was started on 20 November 2015 at Ginchi Woreda of West Shoa zone in Oromia National Regional State. This protest particularly in this area started first when the local government officials gave the playing ground of students to the investment. Then, schoolchildren started protest while the government started to deal with people again on the issues of the Integrated Master plan of Addis Ababa with the surrounding special Zone of Oromia regional state and the issues of land became the leading question throughout Oromia National Regional State and the serious round of protest started (Ibid).

The protest was widely disseminated throughout Oromia National Regional State and according to the report of EHRP, it was held in 227 places in the region and reported death causalities in this second-round protest from November 2015 to January 2016 approximately more than 149 people were lost their lives (Bertelsmann, 2016). The report of EHRP stated the situation as "after all the killings and mass detentions, the protests continued and forced the government to finally scrap the proposed Development Plan on January 13, 2016. But, scrapping of the Master Plan was too little too late to stop the protests" (EHRP, 2016). The third plump of protest mainly targeted the questions of human rights and democratic rights in the country as well as the justice and compensation for the damaged parts of communities held from 14th January 2016 to 29th February 2016 (EHRP, 2016). The extent of this protest was broader than that of the previous rounds of protests in the region and it happened in around 188 areas and 81 people died during this protest (EHRP, 2016). Hence, the protest was not ended after February 2016 but continued in serious ways until the government announced the 'state of emergence' and command posts control the region especially selected areas to maintain order in the country. This can be considered as the fourth round of protest and after the government declared the state of emergency in the region the silence period in the region and no peace in other words after the state of emergency was declared in Ethiopia ended the protest in the region researcher consider those months as 'no peace no protest' in the region. On the policy which the government declared to maintain peace in the country called 'state of emergency policy' researcher conducted some discussions with a few individuals, mainly, scholars and they considered the state of emergency policy was inadequate to bring sustainable peace in the country but this policy reduced destructions of public properties. Specifically, one of the research participants argued that "the government legalized the acts of torture, killings and other brutal action on the people and I didn't think this can be significant role to bring peace in this country at expense of human life". Human rights violations during a protest in widely reported even by international media as government security forces committed an extrajudicial killing; while security forces time and again declined the claim against human rights violations. The perceptions of people towards perpetuated command posts were more pessimistic and they considered security forces not as public protectors but rather as perpetrators and this put into contestation the ownership of the military in Ethiopia; either regime or public. Grassroots communities thought of military forces as their potential threat. To scrutinize the issues in protest; the researcher employed the onion tool of conflict analysis mechanisms because; the Onion illustrates important layers and elements of protest that get built up throughout a contention. The tool might be helpful to identify the dynamics and different layers of questions in the Oromo Protest as position, interest, and needs.

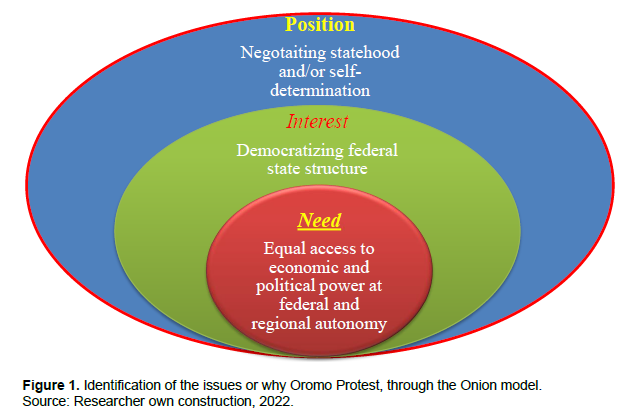

In the Conflict analysis model usually, Need is a non-negotiable issue, while position is an extreme claim. Therefore, it's important to know the appropriate interest and treat it wisely for lasting peace or to avert any issues in conflict. In the case of the Oromo Protest, it seems visible that, the Oromo people are not negotiating their needs which are exercising regional autonomy and equal access to economic and political opportunities at the federal level, while the extreme position of claiming for statehood is serious that the supposed to be treated wisely. Therefore, negotiating on interest which is democratizing the federal state structure is the only way to address the questions of the Oromo people in Ethiopia, that facilitates getting the needs and if the needs are denied the position or negotiating for statehood comes forward forcefully. To scrutinize the protest in Oromia National Regional State researcher utilized three theories and one relevant approach. From the perspective of participatory democratic theory, the protest stemmed from when the community abstained from the process of policy formulation and decision-making. Because people have a far better understanding of their issues and they know the way outs. Though, the government must have high concerns for the aspirations of the community. The protest in the Oromia National Regional State community heard the finished plan and react negatively because the ideas of the community were not incorporated into the project. This shows that in Ethiopia top-down approach to policy formulation and decision-making was not any more comfortable for the community (Figure 1).

Therefore, the absence of public participation in the process of establishing a plan created grievances and mistrust between the people and the government. Hence, let people participate in their affairs and the government has space for their desires and builds a sense of a bottom-up approach to policy formulation and decision-making process in Ethiopia. In perspective to relative deprivation theory, the protest was considered the result of horizontal inequality. Though, this theory was to assist us to emphasize horizontal inequalities in Ethiopia and assumed as the causes of social movement and conflict in different parts of the country. In the case of protest in the Oromia National Regional State, Oromo people feel deprived because of horizontal differences in access to the economy and political positions. Participants of the research repeatedly stressed the issues of discrimination to access the national economy in the country and they considered the economy of the country was handed over by few individuals and the majority of the population in the country was living under the line of absolute poverty. And people believed this economic variety was the result of government policies and programs. Feeling deprived because of horizontal inequalities among communities leads them to protest against the government and it may also shrink the harmonious relationship between the communities through economic lines. In addition to economic inequalities in the country; Oromo people feel as if they are not represented in the government system and the need for absolute representation was another tough issue in Oromia today. Therefore, the existence of horizontal inequalities contributed to the current protest in Oromia National Regional State.

To grasp the historical facts in Ethiopia and its reflection in the protest of the Oromia National Regional State researcher used path dependency theory which emphasizes the trends of history in Ethiopia and helps us to understand the impacts of the past and the present and future. In Ethiopian history historians portrayed differently in the issues of politics, and social and economic facts in the country. Particularly, in the case of Oromo in Ethiopia, different historians claimed from different perspectives. In short, the fact in Ethiopian history was that Ethiopia was aged thousands of years or decades undeniable fact was people were mistreated by their superintendents mainly in the southern, southwestern, and western parts of Ethiopia. In short, the majority of the population in Ethiopia carried different yokes of dominance except for royal families. Though, the fact of Oromo history in Ethiopia was very important in this study. Mainly, the history that needed to consider in this inquiry was the process of Ethiopian state formation and after formed Ethiopia the way people were treated in the country played a paramount role in Ethiopia to have perpetual peace. For example, history revealed that Menelik II utilized modern weapons and European advisors against his opponents those who fought with spears, practiced devastating death on an enormous scale on the Oromo people and between 1868 and 1900, half of all Oromo were killed, around five million people from ten million total population of Oromo people (Asafa, 2007). In addition, people were mistreated on their lands even after the state's formation and they were considered slaves on their forefathers' lands. Hundreds of thousands of gunmen, known as 'naftanya-gebar' system, meaning gun carrier, were dispatched by the past Ethiopian governors into fortified settlements in the Oromo areas (Hasan, 1994). The gun carriers seized vast tracts of Oromo lands, on which the Oromo were forced to work as a laborer. Oromo place names were changed to Amharic and local language and culture were banned. Under the famous emperor Haile Selassie, who took power in 1930, Oromo lands were given to multinational corporations, expelling and decimating local populations. Again, after the Military regime overthrew Emperor Haile Selassie Oromo was continually mistreated by the socialist regime. And the radical change in 1991 brought some shine of hope in Ethiopia to recognize diversity and democratize the country in favor of all vulnerable Ethiopians in general and Oromo people in particular even if the implementation process was still in contestation there was progress in the political structure of Ethiopia.

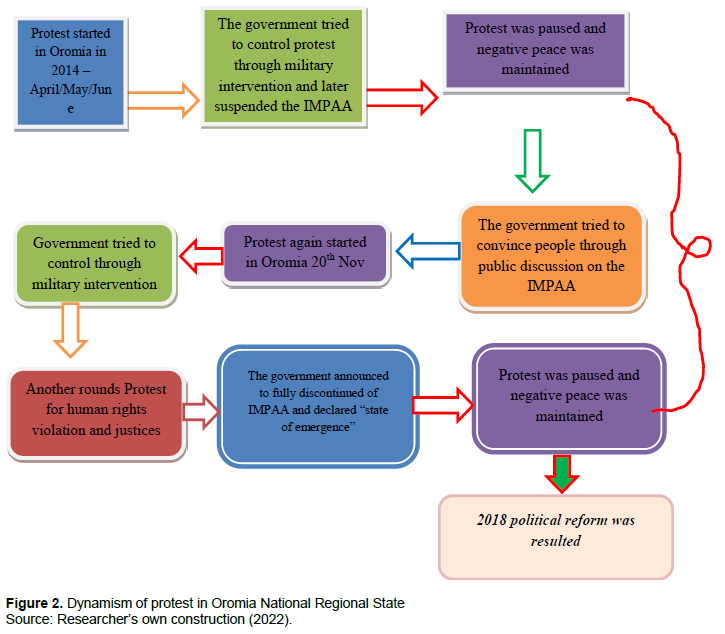

Consequently, those historical facts or past trauma of the Oromo people and people respond sensitively to the issues of land and violation of human rights and others. Oromo started to protest not merely against the present situation but was rooted in history. Therefore, the unhealed historical problem was reflected in the process of protest in the Oromia National Regional State, and the power of the past was a substantial factor in the protest of the Oromo people. In addition, the dynamics of contention approach was important in this study to understand the different cycles of protest in the Oromia National Regional State. The way the government responded to the protest and the result. Figure 2 displays a brief analysis.Then, protest brought about observable political changes in Ethiopia. Following the outbreak of protest in the Oromia National Regional State, the government first took measures on individuals and tried to reform the system by changing individuals starting from the regional office to the kebele level. Then, the government continued to mend the system by public training at different levels, from higher government officials to local farmers which was called "deep reform" (or in Amharic; tilq taddisow) or haareffama gad-fagoo (in Afaan Oromo). In short, this protest alarmed the need of humanizing the government system in the country. Later, unstoppable public pressure through mass protest pushed the ruling regime to be open for reform, and in April 2018 new Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed came to power from the ruling regime came to usher in the democratization process in the country. Therefore, we can conclude that the protest forced the government to reform itself (Figure 2).

Why does Democratic Governance Matters More in Ethiopia?

The democratization process in Ethiopia after 1991 was subjected to the momentous theme in this inquiry to promote sustainable peace. The concepts of democratic governance were grounded on the notions of human development and directly affect the extent of peace in a given country. Though, protests in Oromia National Regional State can be considered a substantial indication of the linkage between democratic governance and sustainable peace in Ethiopia. The trend of democratic governance in Ethiopia was found in the downturn era. To assure this with the simple and observable election process in Ethiopia and Ethiopia experienced elections in 1995, 2000, 2005, 2010, and 2015. From all election periods, the 2005 election was nominated as more democratic rather than other periods of elections because different political parties participated and even if the result was left under question. In 2010 the ruling party won the political completion with 99% and in 2015 the ruling regime officially announced that controlled all sites in parliament and secured by 100% which was noble false in presence of the multiparty system. As the events of the pre-election period, the 2014 protest of Oromia National Regional state counted as a fact of event, and as the post-election events nearly after a few months, the government declared the result of the election protest started in Oromia National Regional State in November of 2015. Democratic governance was based on the universal value of the protection of human rights. Seeking development at the expense of human rights is not development for the people. Similarly, the protest in Oromia National Regional State from 2014 to 2018 tested highly the ways the EPRDF dealt with the crisis. The violation of human rights during protests seriously triggered another round of protests unless the government goes further in democratizing the government institutions. The questions of accountability and transparency were also another important issue in protest of Oromia National Regional State. Participants in different areas claim that the government was not able enough to provide needed social services and corruption and other related problems were very much triggering people to protest. So far, the government considered this a problem of good governance and tried to perform bureaucratic changes in the country. Though the steps of government were considered good they must be packed by well and concrete policy to sustain transparences and accountability in the country.

Democratic governance also constitutes public engagement in policy formulation and the decision-making process (Abdellatif, 2003). In the cases of protest, the study revealed that public participation in Ethiopia was not in the process but after policy, programs, and/or projects engineered by higher political officials it may go down to the public. But in a real democratic governance system, the exegesis of policy, programs, and the project started from the community and fostered by the highest political officials and ratified by the people, and implemented in collaboration. In addition, democratic governance encompasses equal access to political power and economy, spaces for political participation, the supremacy of the constitution in practice not merely in discourse, and other important issues which played a significant role in building sustainable peace in Ethiopia. Therefore, the protest in Oromia National Regional State reflected the high demands for democracy for sustainable peace in the country.

CONCLUSION

Realizing sustainable peace in sub-Saharan African countries has been a challenging issue for scholars, politicians, and other peace activists because of diverged political cultures, economic aspects, and other related social issues. Similarly, Ethiopia carried lots of discrepancies to maintain sustainable peace in the country. In post-1991, the government of Ethiopia launched ethnic-based federalism to resolve past problems and maintain peaceful order in the country. However, the country has faced peace and security-related problems. Though, protests in Oromia National Regional State since 2014 were considered a major national issue in Ethiopia and tested the overall political system in the country. Democracy in the developmental state, especially in Ethiopia, was considered as the end of development or in other words first access to development and then democracy will come. The protest in Oromia National Regional State provides special lessons for the government and also for all Ethiopian people regarding the urgent need for democratic governance to have sustainable peace in the country. This research revealed that there is no development without peace and there is no sustainable peace without democratic governance.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Abbink J (2010). Political culture in Ethiopia: A balance sheet of post-1991 ethnically based federalism. Netherlands: African study center. Available at: |

|

|

Abdellatif AM (2003). Good Governance and Its Relationship to Democracy and Economic Development. Global Forum III on Fighting Corruption and Safeguarding Integrity Seoul 20-31 May 2003. |

|

|

Ake C (1996). Democracy and development in Africa. Brookings Institution. |

|

|

Al Jazeera America (2015). Protesters in Ethiopia reject authoritarian development model. Al Jazeera America 19 December 2015. Available at: |

|

|

Andersen L, Møller B, Stepputat F (2007). Fragile states and insecure people?: violence, security, and statehood in the twenty-first century. Springer. |

|

|

Asafa J (2007). The Concept of Oromummaa and Identity Formation in Contemporary Oromo Society. Sociology Publications and Other Works, 12. Available at: |

|

|

Asafa J (2016). The Oromo National Movement and Gross Human Rights Violations in the Age of globalization. European Scientific Journal 26(5):177-204. |

|

|

Bach JN (2014). EPRDF's Nation-Building: Tinkering with convictions and pragmatism1. Cadernos de Estudos Africanos 27. |

|

|

Bertelsmann S (2016). Ethiopia Country Report. Gütersloh (BTI). Available at: |

|

|

Brietzke PH (1995). Ethiopia's "Leap in the Dark": Federalism and Self-Determination in the new constitution. Journal of African Law 39(1):19-38. |

|

|

Chan S (2002). Liberalism, Democracy and Development. 285 p. |

|

|

Diamond L (2002). Advancing Democratic Governance: A Global Perspective on the Status of Democracy and Directions for International Assistance. Foreign Aid in the National Interest. Available at: |

|

|

Ethiopian Human Rights Project (EHRP) (2016). Oromo protest; 100 days public protest. Addis Ababa: Ethiopian Human Rights project. Available at: |

|

|

Friedman E (1994). Democracy and Capitalism: Asian and American Perspectives Bartley R, Chee CH, Huntington S, Ogata S (eds,). Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1993. The Journal of Asian Studies 53(3):890-892. |

|

|

Galtung J (1967). Theories of peace. A synthetic approach to peace thinking. Oslo: International Peace Research Institute. |

|

|

Garrett RK (2006). Protest in an information society: A review of literature on social movements and new ICTs. Information, Communication and Society 9(2):202-224. |

|

|

Infosheet (2010). Political culture in Ethiopia: a balance sheet of post-1991 ethnically based federalism: Leiden University; African Studies Center. |

|

|

Lyons T (1996). Closing the Transition: The May 1995 Elections in Ethiopia. The Journal of Modern African Studies 34(1):121-142. |

|

|

Lyons T (2011). Ethiopia; assessing risk to stability. Center for strategic and international studies. |

|

|

Micheau AP (1996). The 1991 Transitional Charter of Ethiopia: A New Application of the Self-Determination Principle. P 29. |

|

|

Nizigiyimana DL (2015). The Role of External Actors in Peace-Building and Democratization in Africa: A Comparative Study of Burundi, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). International Journal of Humanities and Social Science 5(9):173-179. |

|

|

Norman WJ (2006). Negotiating nationalism: Nation-building, federalism, and secession in the multinational state. Oxford University Press. |

|

|

Reuters (2015). Ethiopia industrialization drive met by violent protests over land' 19 December 2015. Available at: |

|

|

Sørensen G (1990). Democracy, Dictatorship, and Development. Palgrave Macmillan UK. |

|

|

The Guardian (2015). Stop the killing!': farmland development scheme sparks fatal clashes in Ethiopia. Available at: |

|

|

The Independent (2015). Ethiopia security forces kill up to 50 people in crackdown on peaceful protests. The Independent 17 December 2015. Available at: |

|

|

Wasara SS (2002). Conflict and State Security in the Horn of Africa: Militarization of Civilian Groups. African Journal of Political Science 7(2):39-60. |

|

|

Webel C (2007). Handbook of peace and con?ict studies. In Webel C (ed.), Toward a philosophy and metapsychology of peace. New York: Routledge. |

|

Copyright © 2024 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article.

This article is published under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0