ABSTRACT

This paper presents findings from a study of political violence by party youth wings in sub-Sahara African polities from 1990 to date. Using a case study of Ghana, the research draws some similarities, and or differences in the mechanisms through which youth wings perpetrate violence across other parts of the sub-region. During the December 2016 general elections in Ghana, the aggressive role of party youth wings was very visible, and calls for policy attention. Due to the high stakes involved in wining or retaining state power in Africa, politicians value the organizational abilities of their respective youth groups. However, youth wings in most polities rather engage in aggressive political activities including, vandalizing public property, rioting/violent protests, seizer and control over facilities of public good, militias/vigilantism and electoral violence. And these acts thwart democratic advancement. Drawing on over four years of participant observation in Ghana; extensive analysis of media political discourse across Africa; and relevant secondary data, the author argues that though youth wings are meant to contribute positively to democratic consolidation through peaceful and democratic activities with their mother parties, they mostly rather engage in aggressive, violent politics, annulling the expectation of constructive contribution from the demographic majority in the continent. And this violent politics is generally due to their systemic exclusion from core political and democratic processes by their respective parties. These incendiary acts are catalyzed by increasing youth unemployment; weak institutions or unprofessional state agents; illegitimate electoral systems; political manipulation of social cleavages, and history of violence in societies all mired in patronage political system.

Key words: Youth wing, violence, political party, sub-Sahara Africa, democracy.

Since the early 90s, the logic and practice of democratic pluralism has gradually almost overtaken the hitherto authoritarian regimes in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). And a crucial element among existing and emerging political parties in this multi-party system is the involvement of party youth wings/leagues (PYWs). The phenomenon of partisan youth mobilization and development is visible and growing in the region. These groups are assigned political tasks, especially with mobilizing support for elections. Due to the high stakes involved in wining or retaining state power, politicians have come to value the organizational abilities of their respective youth groups (Bob-Milliar, 2014). Development actors and stakeholders take cognizance of the indispensable role of young people in politics and society. They are the dynamic, energetic portion of every population, making their policy contribution crucial. Therefore, systematic youth involvement in politics is likely to widen the scope of policies, which benefits largely the youth bulge in Africa (Maliki and Inokoba, 2011). By implication, having YWs affiliated to parties seeking government positions is a constructive idea, once it is a way of nurturing young people into leadership positions.

Historically, youth played a central role in the struggles against colonial occupation in individual states and the continent at large, but were written off after a few decades as a ‘lost generation’ (Everatt, 2000), characterized by violence and cruelty. Evarett’s observation is based on how a largely young generation in South Africa fought against Apartheid, but were abandoned later in favour of older generation. Therefore, young people became reserved in policy processes for a few decades.

However, quite recent burgeoning literature offers a new trend. Youth groups are increasingly participating in several dynamics of African politics (Bohler-Muller and van der Merwe, 2011), regarding themselves as instruments for change, liberation movements and democratic transitions. This ambition of the youth is fuelled by the democratizing effect that swept through the continent from the 90s, which came with corresponding multi-party system. Hence different and contesting political parties usually need extra hands that are preferably vibrant and capable of influencing the grassroots with party ideologies. But party YWs still seem not to find any hold in mainstream politics-being manipulated by political entrepreneurs. With their associated parties, “they are at the center and the periphery; they are at the forefront and at the margins; they are misempowered agents, and they are hapless victims; they are everywhere and nowhere, everything and nothing” (Olaiya, 2014:3). This suggests fair and foul ability and potential of youth groups, as well as their inability to break into the main system.

Most political parties draw considerable strength from their respective PYWs, whose core duty it is to broaden the influence of their parties across the state. A few examples of political parties with active PYWs in Africa include: African National Congress (ANC-South Africa), Zimbabwe African National Union - Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), Chama cha Mapin-duzi (CCM-Tanzania), Kenya African National Union (KANU-Kenya) and National Democratic Congress (NDC-Ghana) (Kanyinga and Murimi, 2002; Laakso, 2007; Bob-Milliar, 2014).

Whilst some YWs are extinct-banned or dissolved, others are still active throughout the political cycle. Yet others are dormant-only become active during elections. YWs of parties mostly become kind of pseudonym for foot soldiers or political thugs, engaging in crimes against opponents and civilians. Nevertheless, others become recognized leaders, co-opted and offered token positions to further organize others and strengthen party influence (Olaiya, 2014).

The phenomenon of party YWs has provoked political violence across the continent in both past and contemporary times, and has attracted raging debate in academic and policy circles, concerning the desirability of YWs in politics (Abbink, 2005; Van Gyampo, 2012). Two opposite schools of thought have emerged regarding the involvement or potential participation of youth groups in the political landscape: The youth-wing optimists and the youth-wing pessimists.

For the optimist, youth political involvement is germane, can consolidate democracy and promote sustained growth. They highlight civic forums, recruitment and participation in elections and youth leadership debates as some participatory processes, that broaden youth’s knowledge and understanding of government structures and functions, and inter alia, reduces the generational gap in political participation (Imoite, 2007; Van Gyampo, 2012).

In a sharp contrast, the pessimists such as Abbink, posit that direct or indirect youth political roles in contemporary Africa is mostly violent, and has a generational conflict potential, as young people are easily recruited by political parties sometimes even for armed or criminal activities. And that partisan youth groups are mostly repositories of rage and destruction. Similarly, Laakso (2007) contends that party youth groups across the continent play destructive roles with their respective political mobilizations and related matters, both associated with incumbents and opposition. Interestingly, this political atmosphere is also common in intra-party competitions.

Demonstratively, partisan youth groups become agents of destabilization of the fairly young and emerging democracies in the continent, as they easily transcend official politics into unconscientious party ‘foot soldiers’, political/ethnic militias and terrorist groups that are constituting increased social problems (Olaiya, 2014), although YWs could contribute to peacebuilding and future leadership (Englert, 2008). Consequently, though involving youth groups in political activities would serve a good purpose, going forward, their recurring violent character across the length and breadth of the continent is equally a source of concern, and needs to be examined and tackled from scholarly and policy perspective.

Against the background highlighted above, this work seeks to establish the overall relationship between past and contemporary political party YWs and political violence in SSA democracies (1990-date). The paper does not just focus on partisan youth groups violence in an individual country or from a general continental perspective. It draws from a case study of Ghana (hailed as a polity with fast consolidating democracy) and tries to establish similarities, and or nuances in PYWs activities in other polities in SSA.

The paper further identifies a quintet of enabling environments that sustain YWs deviant, aggressive political engagements across the sub-region.

Drawing from extant relevant literature, this section attempts to provide operational definitions or meanings of three main concepts: political party, youth (and YWs) and political violence, and how they reflect in SSA. It also traces a brief history of party YWs in the sub-region, as well as the incentives for creating partisan youth groups.

Political party is one of the concepts with very little contestation regarding its definition, nature or functions. Common phrases within the definitions provided by relevant literature include, ‘a group of people’ and ‘desire to govern’. Citing a renowned American political scientist Antony Downs (Hofmeister and Grabow, 2011) define political party as a team which seeks to control the governing apparatus by securing office in a duly constituted election. They also borrow a definition by Giovanni Sartori, that a political party is an organization known by an official label that presents at elections, and is capable of providing candidates for elections and ultimately for public office. Similarly, Akande (2000) and Olaiya (2014) indicate that political parties are groups or a collection of individuals and groups with common political beliefs, ideologies, and orientations, and basically pursuing the goal of controlling government and the apparatuses of administrative power within a state.

Political parties in time and space have, two main goals and ends, beyond the general desire to win and control state apparatus: As agents of political socialization or deepening democratic principles and wooing electorates for power. One crucial expectation of political parties within and without Africa concerns generational inclusion, hence YWs should be legitimate.

Gyimah-Boadi (2007) categorizes political parties in Africa into two: Older parties that emerged victorious from liberation movements and independence struggles. These parties emerged and matured during the dominant single-party and authoritarian systems, survive the recent multi-party democracy and have even beaten of challenges from new pro-democracy and opposition movements. For instance, Zimbabwe African National Union - Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF), Kenya National Union (KANU), United National Independence Party (UNIP), Convention People’s Party (CPP-Ghana), Chama Cha Mapinduzi (CCM) and Parti Democratique de Côte d’Ivoire (PDCI). Also included in this group are the South-west Africa People’s Organization (SWAPO)-Namibia, Frente de libertação de Moçambique (FRElIMO) and the African National Congress (ANC).

The second group comprises new parties: Emerging in the 90s from pro-democracy and opposition movements. A good number of them provided close competition to their old dominating counterparts, whiles others have even won political power. Some of them include the Movement for Multi-Party Democracy (MMD), National Patriotic Party (NPP), Alliance pour la démocratie au Mali/Alliance for Democracy (ADEMA), Alliance for Democracy (AFORD), Social Democratic Party (SDP). Both categories have common attributes that define the political terrain across the continent, including leaning on YWs for political power.

Unlike defining a ‘political party’, the concept ‘youth’ has contentious definitions because of its different societal contexts. From a statistical perspective, the UN (2006) defines ‘youth’, as people between the ages of 15 and 24 years, with no prejudice to other definitions by member states. Also, the AU Youth Charter (Banjul, 2006) adopts the age bracket of 15 to 35 years. This variation also manifests in national youth policies. Resnick and Casale (2014) have identified country specific definitions, with 35 being the maximum age in Ghana, Kenya, South Africa, and Tanzania, while 29 and 25 are the upper limits in Botswana and Zambia, respectively.

From the anthropological and sociological points of view (Kirkpatrick and Martini in Bucholtz, 2002) argue that youth are distinguished from other age groups based on cultural values and ideologies. And that context provides a better definition than a fixed age-group specification, from the positivists’ perspective. Hence Burton in Bucholtz (2002) contents that teenagers in developed societies may differently experience adolescence as a distinctive life stage due to economic and other constraints that moves them into adult responsibilities faster than their opposite counterparts. Additionally, a lack of sharp age and role distinction between young parents and their children in some societies makes a universally accepted definition of youth difficult. UNESCO (n.d.) contends that age limit has been increasing, as higher levels of unemployment and cost of establishing an independent household puts many young people into a prolonged period of dependency. In the African context, the aspect of independence has made the definition of youth in the continent extremely difficult, as limited economic opportunities force people to settle late in life compared to other developed continents.

The operational definition in this work is borrowed from the AU Youth Charter, which adopts the age bracket of 15 to 35 years. By the lower age limit, most youngsters enter into high school (where they are exposed to ideas of politics and state governance/ leadership), and by 35, most people are independent to take major decision for themselves, including joining a political party.

This paper defines party YW as any organized group of individuals falling within the defined age bracket, who subscribe to and are willing to execute the ideologies/ objectives/plans of a political party. Mostly, YWs are blends of undereducated, unemployed/underemployed and secondary/tertiary/learned citizens, each cohort commonly known for acts or duties (Bob-Milliar, 2014; Resnick and Casale, 2014).

What makes the phenomenon important is that youth constitute 70% of the Africa’s population (UNECA and UNPY, 2011), while youth political violence seem to be increasing by the factor of population increase as well. Therefore, there is need to examine this worrying issue for improved policy engagement with this majority group in order to reap a demographic dividend not a curse.

There is a near convergence regarding the definition of political violence; just like political party. That is, politically motivated atrocities, small or large scale. According to Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset (ACLED), an institute concerned with comprehensive public collection of political violence and protest data for developing states, “political violence is the use of force by a group with a political purpose or motivation” (2015a:1). And that an incidence is regarded as politically violent when in an altercation, force is used by one or more groups to a political end.

Dumouchel (2012) gives a similar definition of political violence, as violence committed in the light of political conflict, or influenced by political matters. He adds that political violence unites and divides as well. The division comes when enemies and targets are identified, whilst unity emerges among members in one camp with a common foe to fight against. Quite specifically, political violence refers to organized violence intended to overturn or weaken the state; violence committed by incumbents against political rivals, as well as violence not involving the state directly but against opponents in politics, e.g. confrontations between the loyalists of ZANU-PF and MDC in Zimbabwe (Breen-Smith, 2012).

According to ACLED (2015a), violence of political character includes, but not limited to, violence and assaults against civilians or political rivals and rioting (violent demonstrations/protests). This atmosphere usually heightens around elections, especially in Africa, where high stakes are placed on elections and consequent political power (Bob-Milliar, 2014). ACLED points out some active politically violent actors, including rebels, militias, and organized political groups who interact over issues of political power (that is, territorial control, government control and access to resources).

From the few definitions above, it is suggestive how destructive incidents of violence are to the democratic advancement of polities, and especially the emerging democracies in Africa. Evidently, party affiliated YWs are active provocateurs of political violence in the region, leading to rising tensions among political parties-a torn in the democratization trajectory.

PARTY YOUTH WING ACTIVITIES IN GHANA

The Convention People’s Party youth wing, known as Nkrumah’s ‘Veranda Boys’ set the pace for PYWs in Ghana, as Kwame Nkrumah (first post-colonial president) steered his ‘Veranda Boys’ (mostly party youth) to a successful political sovereignty from the British, being the first country in SSA (Resnick and Casale, 2014:1175). Since then, successive political parties have replicated the norm of having youth groups aligned to them to date (Gyimah-Boadi, 2007). As indicated previously, the reliance on youth mobilization for political power is globally recognized and growing. And this scenario is not different in Ghana, as each political party tries to garner support from their youth branches, basically for grassroots mobilization.

There are twenty-four (24) registered political parties in Ghana (Electoral Commission of Ghana-EC, 2016a), some of which include Convention People's Party (CPP),

People’s National Convention (PNC),

National Democratic Congress (NDC) and

New Patriotic Party (NPP). These four are preferred for mention in research on PYWs because each of them has governed the country since independence-1957, with the crucial support of youth groups. While the first two; CPP and PNC ruled in the checkered regimes from independence till 1992, the last two, NDC (main opposition) and NPP (incumbent) have dominated politics and alternated power in the West African country for 24 years of uninterrupted multi-party democracy (this period is known constitutionally as the Fourth Republic). The NDC and NPP have gained domestic and international notoriety for their constant association with youth arms such as ‘Azoka’ (for NDC) and ‘Invincible Forces’ (for NPP). In Ghana’s current Fourth Republic from 1992, these two PYWs pose greater threat in terms of aggressive politics due to their numerical strength, and almost equal in several dimensions (Van Gyampo, 2012; Bob-Milliar, 2014).

The two political parties of focus have created positions such as youth organizer, and communication officers for their youth leagues. However, partisan youth activities seem to be mere expressions of support for leaders. YWs are not substantially integrated into their parent parties. This is in line with Kanyadudi (2010) that youth groups in SSA are at the peripheries regarding core matters of their parties. Although PYWs in Ghana are not integrated systematically into mainstream politics, they are associated with a number of activities, in their attempt to advance the fortunes of their parent parties: Creating awareness on parties’ ideologies, partaking in elections related matters (voter registration; elections monitoring-polling agents); nurturing political leaders; promoting party manifestoes; fund raising peaceful protests; rioting/violent protests; parties private securities; seizing and controlling facilities of public goods; and election violence, outlined subsequently.

First, the creation of awareness on parties’ ideologies is a core role played by PYWs in Ghana to make the presence of their parties felt across the country. NDC and NPP youth often chant their party slogans through any available medium in order to woo more supporters. They also help to shape these ideologies and political engagements of their parent parties, though not much as expected by policy think tanks. The labor intensive nature of SSA politics, by extension Ghanaian politics makes it a core responsibility for PYWs to reach the remotest parts of the state with what their parties stand for (Van Gyampo, 2012; Bo-Milliar, 2014). Hence, it is ordinarily expected that the more effective the youth machinery of a party the more popular the party, and the greater the number of its sympathizers, and ultimately its chances of acceding to power.

Second, in their bid to further translate awareness creation to convincing citizens and electorates about their parent parties national plan, NDC and NPP youth actively communicate and transmit the parties manifestoes from urban areas to rural/hinterlands throughout the Fourth Republic. As Bob-Milliar (2014), PYWs in the country partake in drafting and defending parties manifestoes, and actively disseminate the content of their plans of action in attempts to win voters. YWs therefore play an important role in developing their respective party manifestoes and policy positions which can directly or indirectly shape the direction of national development and public policy.

Another partisan role by YWs is by partaking in elections related matters (voter registration, elections monitoring-polling agents). An important attribute of the Fourth Republic of Ghana has been the crucially active role played by NDC and NPP PYWs (‘foot soldiers’) throughout each electoral cycle; monitoring voter registration and voting exercises. According to Van Gyampo (2012:153), this monitoring and observer duty has significantly promoted fairness and transparency in the electioneering process; elements very necessary for legitimizing and accepting elections results. In the reverse, however, PYWs monitoring of elections has its disadvantages as well. YW of NDC and NPP have engaged in fiery clashes at polling centers or electoral areas, instead of maintaining calm as requite by the EC. For instance, tension mounted between the ruling NDC’s youth arm, ‘Azoka Boys’ and the opposition NPP’s ‘Bolga Bull Dogs’ in 2015, during a by-election in the Talensi constituency in Northern Ghana (StarrFMOnline, 7 July 2015). Such violent clashes continue to be witnessed by Ghanaians mostly during campaigns (including around the December 2016 elections)- reaffirming the destructive potential of party youth or youth movements in general (Abbink, 2005).

Furthermore, PYWs in Ghana are nurturing grounds or springboards for political leaders. Thus, youth groups contribute to leadership modeling. The NDC and NPP YWs are known for producing leaders in the shape of party organizers and parliamentary representatives. For instance, the immediate past employment minister (Haruna Iddrisu) also a member of parliament, was an NDC youth organizer. Elite politicians knowing the agency of young leaders regarding grassroots mobilization encourage the training of young leaders, as this guarantees future existence of parties. This sounds positive for democratic advancement of the region, once embracing youth leadership will bring new issues into party politics. However, the author agree with the assertion that this claim of leadership training and mentorship is nothing but tokenistic (Honwana, 2013), cunning move from elites to produce ‘deviant boys’ movements who serve as foot soldiers especially against dissent and opposition, and to entrench perverse patronage and rent seeking. This leads to violence and mistrust in the political circles of the country, as violence is a signal of loyalty and a likely channel for recognition and reward.

In addition, PYWs occasionally undertake fundraising exercises to support their respective parties. Fundraising activities for political parties is crucial among parties in Ghana and quite ubiquitous in the sub-region, where states have little, and mostly not committed to funding political parties. Since any meaningful party activity can rarely succeed without adequate funds, young cadres usually organize fundraising activities to solicit funds from sympathizers and core members. Through the sales of party cards and paraphernalia, NDC and NPP YWs have generated some funds for their respective parties (Van Gyampo, 2012:154). However, core decisions on the use of these funds mostly lie exclusively with the elites. But youth leagues’ continuous active engagement in party funds generation might be to accrue some personal wealth and resources (Kanyinga and Murimi, 2002).

Peaceful protests/demonstrations are part of the mechanisms through which these groups in Ghana have represented their parent parties. These peaceful protestations are meant to mount pressure on leaderships and governments especially against (perceived) bad policies. For example, the NPP youth aligned movement, Alliance for Change, caused a marked demonstration in 1995 against increased VAT by the then NDC government, while the NDC youth influenced a massive pressure movement (Committee For Joint Action) in 2005 against what they termed as ‘bad governance’, and ‘economic hardship’ caused by the ruling NPP (Bob-Milliar, 2014:137-138). Such peace matches do not only target opposing parties, but sometimes, intra-party protests are also staged by these party activists. Though non-violent, these protests may turn violent or may become targets of violent actions by other groups, including especially state security or other armed political groups, causing public disorder (ACLED, 2015b). This reduces the possibility of holding governments accountable. And mostly, such policy-based protests in Ghana produce insignificant change, given their partisan coloration-making it difficult for neutral public support.

Adding to the above, and in sharp contrast, PYWs are known for contributing to or perpetrating electoral or election violence in Ghana. Elections related violence such as snatching of ballot boxes, voter and opponent intimidation have characterized Ghana’s elections since 1992, and such acts are directly or indirectly traced to youth groups (Bob-Milliar, 2012). According to the Center for African Democratic Affairs-CADA (2012), the situation is catalyzed by the patronage system that has engulfed the nation’s politics coupled with weak security/deliberate acts by politicians and unprofessional security agents. In addition, the risk of election violence may be higher in polities like Ghana, where there is intensive political competition and parties have genuine possibilities to change existing power relations. Having alternated power for at least eight years each since 1992, both NDC and NPP have fairly equal chances of securing power, making their YWs more prone to aggression.

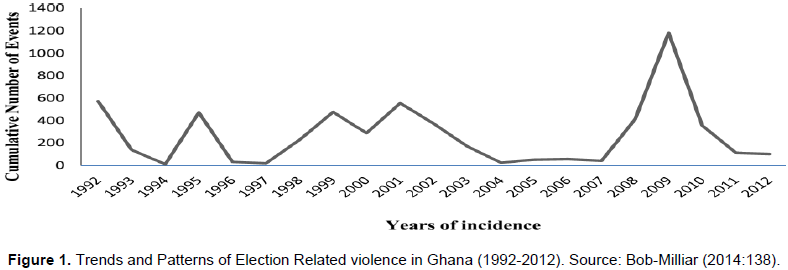

Figure 1 shows the trend of electoral violence recorded in the country. The graph depicts a decline in elections violence since 2010, of which PYWs are the main actors. It indicates that since reintroduction of multiparty system in 1992, election violence has been an on-and-off incidence, which makes any prediction quite difficult. But the sharp decline from 2010 might be a positive sign. However, the series of clashes witnessed leading to and after the December 2016 elections increase the level of unpredictability of the situation.

Similar to election violence, rioting and vandalism are also traced to partisan YWs in Ghana since the inception of multi-party system. YWs have engaged in violent, chaotic demonstrations or spontaneous acts in each regime. For instance, party foot soldiers vandalize their own party property, including campaign cars, party paraphernalia, office buildings etc. For example, some members of the NDCYW in the Wa West Constituency of the party in the Upper West Region set ablaze the party’s office and the party chairman’s car in the constituency, in protest against the appointment of District Chief Executive they did not favor (Nti, 2016, adomonline.com). Similarly, members to the NPPYW vandalized their party's offices in Winneba constituency, locked up the offices, also in protests against an appointment by then president Kuffuor (General News, March 22, 2004). These acts of deviance affect their respective parties more than their opponents or the general public.

Unlawful seizer and control over facilities of public good has become a common practice by party youth movements in Ghana, as victorious party foot soldiers usually unlawfully seize patronage facilities and objects such as bus terminals, in order to seek rents for themselves and their cronies, as rewards for their vigorous campaigns (including violence) to win power. For instance, the NPP YW confiscated and controlled public revenue generating property, including office buildings, cars, toll bridges, public toilets, and lorry parks (or bus terminals), when the party won power in 2001. Consequently, and as the norm continued, the NDC youth wing also forcibly took these socio-economic ventures from the NPP occupants when their mother party beat the NPP in the 2008 polls (Bob-Milliar, 2014:137). The scenario continuous after NPP won the December 2016 elections, as its youth are engaging in the confiscation and occupancy of similar ventures stated above across the country. This reechoes (Laakso, 2007), that YWs resort to and succumb to violence for recognition and reward thereafter.

Finally, both NDC and NPP are known for their preference for pseudo/private security, recruited from within the YWs, for occasions and offices they deem confidential (CADA, 2012). This preference for private security from within appears to be due to trust issues with state security; hence recruiting and using one of your own reduces the risk of betrayal. However, CADA chides parties for engaging in such practice. That the recruitment of physically built men (known in local parlance as ‘macho men’) parallel to state security is a threat to peace, as opposing party security mostly clash violently, but the phenomenon still continues. As stated earlier, it is suggestive that the readiness of some young activists for such roles could be their quest for livelihood, due to unemployment, as well as for patronage politicians to use them in intimidating opponents and entrenching power for rents. Although private partisan security could augment state security, their political identity itself raises the vexed question of how professional they can operate?

In a nutshell, a close assessment of the activities of PYWs in Ghana reveals that, partisan YWs are instrumentalized for or engage in both violent and non-violent political participation, which implies they embody both hope and despair. Some of their activities have the potential to contribute to democratic consolidation. This research labels such peaceful/nonviolent activities as constructive engagements, including creating awareness; elections monitoring; leadership training; manifestoes drafting; fundraising and peaceful protests/ demonstrations.

Conversely, they also exhibit violence, which is called destructive engagements, such as vandalizing public property; rioting/violent protests, seizer and control over public property and election violence. Because such activities have political and democratic destabilization effect, hence are not usually constitutionally permissible. Although the constructive activities appear to be more than the destructive ones, evidence indicate that the violent or destructive engagements have more impact (negative), which strengthens my position that PYWs constructive activities are not substantive enough. Hence YWs are systematically excluded, and manipulated for destruction. This politics of aggression limits domestic and international efforts to advance democracy in Ghana and SSA at large.

Therefore, in establishing the uniqueness or otherwise of the Ghana experience, the next section tries to situate this case study in other polities in SSA, in order to ascertain any similarities or variance of PYW activities (especially the destructive ones).

YOUTH WINGS VIOLENCE: GHANA IN SSA SPECTRUM

As stated in the previous section, this part of the work presents a comparative analysis of PYWs violence as observed in the case of Ghana visa a vis other SSA democracies. Although youth political violence became a common characteristic of the Huntingtonian ‘third wave’ of democracy that swept through Africa from the last decades of the 20th century (Kagwanja, 2005), this political aggression varied from one state to the other, and such is still the case. How, then, do destructive activities of PYWs vary between Ghana and its SSA counterparts and what may have accounted for the nuances? However, before proceeding to the destructive PYW activities, which is the main focus, some constructive engagements (elsewhere in SSA excepting Ghana) need to be summarily identified.

BRIEF BACKGROUND OF CONSTRUCTIVE ACTIVITIES

The most common constructive PYW activities one can identify similar to the case in Ghana, include manifesto drafting, elections monitoring, leadership training and awareness creation. Kanyadudi (2010:17) reveals that party youth in Tanzania have contributed though anecdotally, to their mother parties manifestoes, while serving as grounds for mentoring future political leaders. Similarly, Sokupa (n.d.) indicates that the ANC Youth League was not only positioned to mobilize young people towards the vision of the party. It was responsible for spreading the original ideology of the party, and was able to broadly influence the citizenry, who rallied behind the ANC’s war of liberalization from the Apartheid regime. And also, that the party’s youth arm is an active player in drafting its manifesto, while training political leaders from the ranks of their youth league. However, one constructive activity; fund raising, does not appear to be a common PYW activity in other polities, observed with youth leagues in Ghana, as extensive research fails to gather such evidence. But all the above constructive PYWs engagements point to the fact that political parties ride on the backs of their youth organizations in order to survive the rigorous competition in the political arena. Nevertheless, as argued earlier, these suppose official inclusion of party youth is mostly window-dressing, and moves for ‘laborers’ for political power or elites’ personal issues (Honwana, 2013). This is because, PYWs are systematically at the peripheries of important political decisions although their age regime forms the majority, and should be given priority in policy formulations. Two main reasons explain why the youth are rarely recognized, though they fight vigorously for their mother parties, both of which work in tandem; first, is the deliberate attempt by the elites to relegate young people to the periphery; second, is the inability of the youth themselves to take visible strategic positions and highlight their own contributions (Kanyadudi, 2010). This means that young cadres are not able to have much agency due to structural arrangements that make them a ‘lost generation’. And so, they end up perpetrating or being used in provoking and undertaking a host of destructive activities within and even sometimes without the political sphere. What, then are such violent/ destructive political endeavors orchestrated by PYWs elsewhere in SSA? And how related are they to the case of Ghana?

First, the issue of pseudo/private party security appears not to be unique to Ghana. Both incumbent and opposition parties are notorious for training and using their young followers as party ‘foot soldiers’/security/so-called task forces in several polities in the sub-region. For instance, the African Research Institute (ARI) reveals that the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) and the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) in Sierra Leone have been accused of allegedly recruiting and using their youth wing ‘task forces’ for party and personal security (ARI, 20011:3). The ZANU-PF of Zimbabwe also privatized their security arm called ‘Green Bombers’ (Laakso, 2007:245), while the KANU in Kenya was cited for the use of youth for KANU as guards, in place of state security (Mehler, 2007:231). Interestingly, international and state builders have tried to restructure and strengthen the security sector in SSA, yet parties and individual politicians continuously stick to their own ‘trusted’ young security details for protection, arguing that when politics reaches its apex, politicians can no more trust state security officers- “man’s best servant is him- or herself”, parties have often argued (Enria, 2015:651). Despite the (attempted) justifications given by politicians, it is reasoned that preference is given to private and party security because they mostly indulge in activities that are not officially sanctioned, hence professional state security might be hesitant in such context. As stated earlier, though youth wing security and vigilantism could assist the mostly inadequate state security, their overly partisan character poses sever danger to SSA countries already grappling with security issue Closely linked to pseudo/private security, but evidently non-characteristic of Ghana’s PYWs, is the phenomenon of party affiliated youth militias, who are party-transacted. “Political militias are a more diverse set of violent actors, who are often created for a specific purpose or during a specific time period […] and for the furtherance of a political purpose by violence. These organizations are not seeking the removal of a national power, but are typically supported, armed by, or allied with a political elite and act towards a goal defined by these elites or larger political movements. Militias operate in conjunction, or in alliance, with a recognized government, governor, military leader, rebel organization or opposition group. […] These groups are not subsumed within the category of government or opposition, but are noted as an armed, distinct, yet associated, wing” (ACLED, 2015a:3). The spread of multi-party politics in Africa is accompanied with partisan youth militias in regimes such as in Kenya, Cameroon, Malawi and most recently in Zimbabwe and Nigeria (Abbink, 2005:15).

What appears to worsen the menace of partisan youth militias is when the phenomenon is tinged with ethnic cleavages. According to Peter Kagwanja, between 1991 and 1998, politically motivated ‘tribal militias’ targeting such ethnic communities as Maasai Morans, Kalenjin Warrits, Chinkororo (Kisii), Sungu Sungu (Kuria) and Kaya Mbombo (Digo of the Kenya coast), claimed an approximated 3,000 lives and displaced nearly half a million Kenyans. From 2002 this politico-ethnic youth militia violence was exacerbated by the formation of ethnic political parties such as the National Alliance for Change (NAC), which brought together the country’s largest groups; Kikuyu, Kambaand and Luhya, representing more than half of Kenya’s then 31 million populaces (Kagwanja, 2005:57). And this idea was allegedly spearheaded by Kibaki against Moi, who was accused of massaging elections results since 1992. Interestingly, atrocities of militias also emerge in areas where the ‘big men’ fail to honor promises to their YWs, in which case even the elites themselves are not safe (Laakso, 2007).

Similar (but greater in magnitude) to the case of Ghana, rioting and vandalism is one of the destructive activities of partisan youth in other parts of SSA, as other PYWs have demonstrated violently or spontaneously in disorganized, politically motivated matters. From the 90s, KANU and the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) were both complicit of mobilizing their respective youth groups in fierce confrontations for state power (Kagwanja, 2005). President Daniel arap Moi used the KANU youth wing for monitoring and publicly brutalizing dissent and political opponents. In the words of Kagwanja, KANU youth terrorized and extorted owners of commuter buses, taxis and kiosk businesses as well vendors and hawkers (Kagwanja, 2005:55). Other political youth rioters include early 2000s radicalized youth for Saani Abacha in the Niger and Gbagbo’s young patriots in Cote d’I viore (Gavin:2007:223), who have engaged in a wide variety of violence, including property destruction, battling other armed groups (security forces, private security firms, etc.) or in violence against unarmed individuals (ACLED, 2015a). The three examples on rioting and vandalism above, however, do not reflect rioting in Ghana, as PYWs in the country mostly riot in reaction to unpopular political decisions or when they decide to distort opponents mostly recording relatively not much casualties. Also, severe damage is usually done to mother parties’ property in Ghana unlike PYWs in polities like Kenya and Zimbabwe, who are mostly entirely opponents-focused (Laakso, 2007). The dangerous trend is that perpetrators rarely get (substantially) prosecuted, suggesting the systemic backing of such acts by political patrons.

Also, electoral or election violence appears to have gained (near) ubiquity in SSA, not just the case of Ghana, this research gathers. A crucial destructive PYWs activity which has gained immense attention from governments,policy think tanks, development actors, scholars and citizens in general is elections related conflicts. This explains my earlier submission about the high stakes in SSA politics of patronage. The mention of a few countries like Kenya, Cote d’Ivoire, Sierra Leone, has always rung the bitter history of politically motivated elections conflicts. And in most of the cases, the youth are reported to have been complicit themselves or manipulated by power-drank, self-seeking politicians (Kagwanja, 2005). ‘Task forces’ among the AFRC youth wing in Sierra Leone were ordered to intimidate voters and break up opposition rallies (in 2007) before their loyalty was acknowledged. The youth are often hired by some politicians to engage in violent activities against real or perceived political opponents in the country (ARI, 20011:3). And this has been the case in all the multi-party general elections held in the country between 1992 and 2007. Long-serving ZANU-PF is also recorded to have ridden on the back of its YWs to intimidate, attack and even seize voter cards of perceived opponents in the 2007 elections (Laakso, 2007:245).

On the incidence of the 2007/8 election violence in Kenya, the United Nations Organization for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) reveals that youth vigilantes aligned to the Orange Democratic Movement targeted perceived supporters of the Party for National Unity supporters linked to the Kikuyu, Kisii and Luyha communities, during which the victims’ property, homes were burnt and shops looted, leading to the 2007 election violence (2008:8-9).

However, in relative terms, countries including Tanzania experience insignificant PYWs violence due largely to the CCM monopoly of politics/power (no political tension) and the socialization/nationalization programme introduced by Nyerere (Kanyadudi, 2010:17). These two reasons have also been advanced by Shayo (2005), Shaba (2007) and Yang (2008), to largely contribute to the relatively tranquil political atmosphere in Tanzania, especially compared to its Eastern African neighbors. Interestingly, Botswana’s relative safety from PYWs violence stems from the traditional limitation of young people from active politics (IDEA, 2006:9). But it would be suggested that the mono-polar system, dominated by the Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) could equally count as a contributing factor. Botswana and Tanzania are unlike the tension-ridden duopoly in Ghana and Kenya, which usually comes with PYWs of equal forces, making the battlefield very tensed.

In summary, most of the destructive PYWs activities witnessed in Ghana also feature in several other countries in SSA. The difference between the case of Ghana and countries like Kenya, Zimbabwe and Cote d’Ivoire lies in the less severe form of violence especially related to elections in Ghana. And this might explain why Bob-Milliar (2014) describes PYWs violence in Ghana as low intensity. One crucial destructive activity which is not recorded in Ghana, likewise countries like Botswana and Tanzania is partisan (sometimes ethnic) militias, witnessed in especially Kenya. This means, PYWs violence vary from polity to the other, depending on a number of factors underlying the political atmosphere, that permits PYWs to perpetrate or being used for violence or restrain them from been drawn into violent acts. It is acknowledge that PYW violence in SSA countries may differ based partly on the political histories of each. Given that almost the entire continent was colonized and still operates on political institutional basics in post-independence Africa (Claude Ake, 1996), the difference in colonial tactics across the region have produced variations in African political systems and engagements.

DRIVERS OF PARTY YOUTH VIOLENCE

Having observed the (potential) violence of YWs across emerging SSA democracies in the previous sections, this part of the work traces the (likely) conditions that generate party YW-linked political hostilities. An important point to note is that the mere formation or existence of partisan YWs does not make political violence unavoidable or automatic. Political violence is generally triggered by the structures and actors within institutional arenas. Youth are not naturally inclined to cause violence or social destruction, but the ineffectiveness of a socio-political and moral order in the wider society together with the degree of governability of polities underpin such acts (Abbink, 2005). Therefore, partisan violence does not affect countries evenly, as realized between the case study of Ghana and its compatriots in SSA. Rather (De Juan, 2012), their occurrence and intensity vary across states and regions.

Hence, the kinds and magnitude of YW insinuated violence in Ghana is bound to be of unequal measure or even very dissimilar to other democracies such as Kenya and Nigeria. In same vein, Botswana and Tanzania are witnessing relative calm regarding PYWs violence due basically to different factors that underpin YW activities in those countries. This research has identified five (5) chief proxies for the eruption or escalation of political violence attributable to partisan youth groups: Illegitimate/non-transparent electoral process, history of violence, lack of economic opportunities, uncompromising social cleavages and limited state capacity or unprofessional state actors.

Firstly, illegitimate/non-transparent electoral processes and opaque transitional processes could easily plunge opposing parties through their respective YWs into violence. As elections in the sub-region usually come with uncertainty, high stakes and mistrust, party affiliated youth groups mostly challenge the legitimacy of the wining party, leading to clashes with the victor youth wing (Gyimah-Boadi, 2007). The earlier mention of Kenya and Zimbabwe as hotspots for elections violence could be indicative that electoral processes are manipulated.

Hence, the tacit quest for manipulation of electoral results by parties especially incumbents to monopolize political power across the continent results in YW mobilization. Lindberg (2009) christens such polities as hegemonic electoral authoritarians. Thus, opposition parties are welcome into the competition but the incumbent dictates the pace of the competition and ultimately the results. This condition is the bane of most democracies in the sub-region (Kofi Annan, 2015) as suspicious electoral processes have due to youth reactions wrecked states from decades of attempted democratization.

Secondly, limited state capacity or structural weakness also breeds unguarded actions of political YWs. Uncontrolled exhibition of violence by partisan youth indicates weak organizational/state capacities, hence limited capacity/quality of state monopoly over the use of violence. Most emerging SSA polities exhibit symptoms of weak statehood. Their capabilities to design and implement rigorous political institutions backed by professional security to exercise their imperative of containing such nascent activities by YWs fall short (Mehler, 2007). However, ACLED (2015b) might be right in positing that some states’ failure to control PYWs are deliberate moves by mostly incumbents to manipulate crucial state agents like the security to politicians’ advantage. This is corroborated by previous indications that electoral violence in countries such as Ghana, Kenya and Zimbabwe have not been traced to institutional weaknesses, but largely due to attempted (manipulations), which mostly goes with impunity. This is further substantiated by the fact that Tanzania and Botswana equally suffer the universal narrative of institutional weakness in SSA, but do not witness these PYWs deviance.

On why PYWs are prevalent in weak polities, ACLED (2015b) advances two main reasons: First, YWs could boost limited penetrative power of state security. Second, governments try to evade accountability for YW violent perpetrators (as they are mostly transacted by the elites), and hence using these groups places no direct responsibility on the shoulders of official institutions or affiliated political parties. My observation in Ghanaian political circles is that such acts are either even backed by party communication teams or the parent parties keep mute while their opponents condemn, only to repeat similar incidents in their own turn. Therefore, though youth PYWs violence hinge on weakly institutionalized polities or non-cohesive political institutions (Besley and Persson, 2011), this seeming system weakness might just be a source of agency for hegemonic democratic rulers to weaken opponents and entrench their position.

The third incentive is that uncompromising social cleavages (e.g. ethnic/religious/sectoral) in countries also count as a potent catalyst in spurring political violence through PYWs, as elites instrumentalize partisan youth thugs to attack rivals. This might be attributed to the failure of states to nationalize their citizens through civic education, or could be a tool by especially ethnic majorities to dominate the political field. For decades, some African political elites have ridden on the backs of YWs to commit atrocities against ethnic or sectoral opponents. This happens due to crystalized or sharp divisions and ethnic hurting going on in most polities, as both ethnic or religious groups and political elites place expectations on each other, and works in tandem (IDEA, 2007). ‘Political ethnicity’-playing ethnic cards in politics, was a brainchild of the colonialists who consolidated power by setting ethnic groups against others (Kanyinga and Murimi, 2002). Contentious as this may sound, it mirrors the contemporary democracies of Africa. Combing through both thriving and failing democracies in the region, it is known that most political parties are not formed on ethnic identities, but they mobilize along ethnic identities (Erdmann, 2007). The reported dominance of ethnic narrative in Kenyan’s competitive elections together with several other countries in the region confirms how ethnic identities can be used as a weapon by elites and their foot soldiers to destabilize peace and democratic advancement for that matter (Kagwanja, 2005; Kanyinga and Murimi, 2002).

Since the reintroduction of pluralist democracy in the 1990s, politically instigated ethnic violence has resulted in considerable death, injury, human displacement, and the destruction of public and private property. The history of this violence is deeply entrenched, as old as Kenya itself; but these problems will prevail without changes to the political culture” (Wepundi, 2012:1). This conforms with Frances Steward’s development research, which reveals that horizontal inequalities had a huge impact on electoral violence, that brought untold pain on the populace (Stewart, 2010).

In Ghana, Bossuroy (2011) observes only traces of ethnic vote pattern, which by implication, does not court PYWs violence. But as an ordinary citizen of the country, the author still observes attempts by politicians and their attached YWs to make ethnocentric statements. The major restraint to ethnocentric politics in Ghana is the strict requirement by the EC for all parties to have offices and executives in all 275 constituencies, while prohibiting ethnic or identity-based parties (EC, 2016b). Which means, all parties are invariably of national character, making it difficult for youth movements to target a whole community, as the Kagwanja (2005) and SID (2012) indicated on Kenya. The Kenya case implies that YWs now are ready to canvass political support, through both foul and fair means to for elites from their tribes or religion and invariably against other groups. This implies that multi-party politics is rather giving viable conditions for some African societies to ‘re-ethicize’ instead of democratize.

One other cause of PYWs destruction is history of violence (e.g. civil war or genocide) in a polity gives undue advantage to some elites to manipulate young followers for political purpose, just with a simple regurgitation of a past conflict. Defending how history of violent conflicts can be manipulated politically, Andreas Mehler provides studies (from the 90s to early 2000s) including Cote d’Ivoire, Cameroon, Congo (Brazzaville), Burundi and CAR, where recent past chaos such as coups, civil wars and ethnic cleansing have relapsed but in highly partisan dimensions (2007:197-199).

However, in other similar democracies, such conflicts have not reoccurred. This might be because states concerned have executed their imperatives tactfully; including the strengthening of legal and security sectors (with adept state monopoly over the use of violence) or the spirit of nationalism has penetrated such state. This research reveals that history of conflicts has not significantly influenced political violence through PYWs in the sub-region since 2005, as major sources such as Kagwanja, Bob-Milliar, Enria and Laakso, have all pointed to weak institutions and unemployment as the fundamental incentives.

Finally, poor economies and limited economic opportunities have bred political violence from the angle of PYWs, as stated earlier. Akin to the near ubiquity of electoral violence in SSA (stated above), youth un-employment has been cited by most scholars on partisan youth violence, including John Abbink and Alcinda Honwana, as the major cause of PYWs destruction in SSA. Laakso (2007) argues that the 1990s wave of democratization in Africa often coincided with dwindling economic opportunities especially for the bulging young population. She suggests that political mobilization of groups, including also party YWs has an economic dimension, as both elites and youngsters are incentivized by this paucity of economic opportunities, to undertake ‘politics of extremities’-that is, acts or political behaviors that court violence between or among political parties in a democratic system. Hence, there is a significant relationship between economic wellbeing and political violence, regarding scenarios from African democracies, where struggle for livelihood, can lead to open/high intensity violence.

However, poverty or limited economic opportunities do not automatically yield violence. Rather, some steadily growing economies have suffered political violence, whilst weak and ailing economies have well managed potential political violence, in line with Liisa Laakso counter of the previous point. This means both good and poor economies are at risk. Demonstrating that structural lapses, such as weak legal system, unprofessional security and other human induced factors rather trigger youth violence in SSA democracies rather than weak economies, and this may be the reason why perpetrators seldom get penalized.

Deducing from the above, it is opine in the study that violence by YWs do not happen because young people and their aligned parties or elites are simply blood thirsty or naturally aggressive. A host of factors provide the enabling environment for negative politics by partisan youth groups. The circumstances within which youth political violence thrive span from structural weakness or institutional design to human induced factors. Thus, all SSA polities might be witnessing cases of unemployment, but the difference in the magnitude and nature of PYWs violence between Ghana and Kenya or Kenya and Tanzania, might come from other factors such as social cleavages or unprofessional state agents, which means, there is no stand-alone cause of PYWs aggression. All the causes are intrinsically intertwined needing broad-base or systemic solution to constructively utilize the youth bulge in the region. This suggest that the gloomy picture painted about youth leagues above does not make them liabilities to the state, and therefore should not be involved in matters of states’ interest or democratic processes. There have been examples of prominent politicians and national leaders who are nurtured by YWs, as captured under constructive activities. And this should be encouraged in the political or democratic processes in SSA, as contended by Kanyadudi, in his work on youth leagues in democratization and regional integration in East Africa. Therefore, once the institutional arena becomes more inclusive and unbiased, youth become an effective arm for democratic transformation and political development.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

This paper has attempted to establish that there are more adverse effects of political party youth leagues in political participation in SSA than positive impact. YWs violence in past and in contemporary times threaten the development, stability and consolidation of democracy and political institutions, as youth’s aggressive politics keep weakening the very principles of free and fair participation in multi-party systems. This political violence by PYWs is caused by the systematic marginalization of the youth from core political decisions and mainstream politics by the elites, confining youth to the peripheries of democratic processes. As a result, these vibrant groups of young citizens get desperate to participate substantially, and are been manipulated by patronage politicians to perpetrate political violence to earn them (elites) political and apolitical objectives. YW political violence runs through most emerging democracies in SSA, but varies from one polity to the other based largely on the political culture and attitude or capacity of state institutions and agents. Inferring from the case of Ghana, the systematic exclusion of youth from mainstream democratic processes coupled with increasing youth unemployment mired in patronage politics, force PYWs to engage in destructive activities including rioting or violent protests, vandalizing or destroying public property, electoral violence, pseudo security, seizer and control over revenue-generating facilities of public good.

Relating Ghana to other countries in SSA, the paper gathers that with the exception of seizing and controlling facilities of public good, all the other destructive activities recorded in the country have also been carried out by PYWs in other states (e.g. Kenya and Zimbabwe), albeit of greater magnitude in the other polities. Apart from the destructive activities observed in Ghana, YWs in other places (e.g. Nigeria and Kenya) have developed into partisan and sometimes politico-ethnic militias and vigilantes. But among all PYWs incendiary acts, elections violence appear to be the most common in most polities in the region. However, some few countries (e.g. Botswana and Tanzania) are noted to have witnessed insignificant PYWs violence.

Consequent to these stated destructive acts, youth leagues become ineffective in carrying out constructive political imperatives such as creating awareness on parties’ ideologies, youth debates, electoral duties, leadership in government, and fund raising, peaceful protests/demonstrations (for example against unpopular policies).

Five main incentives for PYWs destruction are identified in SSA, and all these are imbedded in and worsened by the patronage system of politics.

First, lack of economic opportunities in most SSA countries increases the aggressive tendencies of the youth, would usually commit political crimes in order to be acknowledged for reward by self-seeking and power-entrenching politicians and parties. Second, PYWs destruction emanates from nontransparent electoral system. Several youth wing violence across the region stem from flawed elections processes or election results, which force opposing youth leagues into bloodshed. Hence, consolidated democracy can only be built in an atmosphere of moderation, trust, and constructive dissent/disagreement, as put forward by ECA (2005). Third, weak state institutions or unprofessional state agents also catalyze youth league violence, as the web of patronage mostly reduces the professionalism of state agents and the capacity of state institutions to hold culprits responsible. Fourth, social cleavages and history of war or violent conflict could play roles in the manipulation of PYWs for violence, as tribal politicians regurgitate historical, ethnic or sectoral feuds to their young followers who target and attack perceived or actual opponents violently. Finally, social cleavages such as ethnicity have been instrumentalized by some politicians or parties through their YWs in several countries in SSA. And this mostly generates ethno-political violence or conflict, which appears to significantly contribute to the weak democratic systems being witnessed in SSA.Among the five causes of PYWs destruction, the most sensitive triggers are nontransparent electoral/transitional system and weak state capacity or unprofessional state agents, whilst history of war or conflict appears as the weakest cause of PYW violence across the continent.

The above suggests a huge defect with the political system in SSA, hence the largest demographic group, which suffers most from policies are not able to substantially participate in policy decisions, even though they would have the creative potential to do so. Therefore, there is need for frantic efforts to comprehensively integrate young citizens and party followers in political and democratic processes in order to reap the demographic dividend.

The authors have not declared any conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

|

Abbink J (2005). Being young in Africa: The politics of Despair and Renewal. Leiden. Boston. Brill Publishers.

|

|

|

|

ACLED (2015a). Definitions of Political Violence, Agents and Event Types.

View

|

|

|

|

ACLED (2015b). The Conflict Patterns and Role of Pro-Government Militias: Real Time Analysis of Political Violence Across Africa.

View

|

|

|

|

Ake C (1996). Democracy and Development in Africa. Washington. Brookings Institution Press.

|

|

|

|

Annan K (2015). Elections with Integrity in Nigeria: Towards a Fairer More Peaceful World. Kofi Annan Foundation.

View

|

|

|

|

ARI (20011). Old Tricks, Young Guns Elections and violence in Sierra Leone. Briefing 1102. Old-Tricks-Young-Guns. Elections-and-violence-in-Sierra-Leone22ZK27SBXD.pdf.

|

|

|

|

Besley T, Persson T (2011). The Logic of Political Violence. Quart. J. Econ. 126:1411-1445.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Bob-Milliar GM (2012). Political Party Activism in Ghana: Factors Influencing the Decision of the Politically Active to Join a Political Party. Democratization 19(4):668-689.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Bob-Milliar GM (2014). Party Youth Activists and Low-Intensity Electoral Violence in Ghana: A Qualitative Study of Party Foot Soldiers' Activism. Afr. Stud. Quart. 15(1):125-152.

|

|

|

|

Bohler-Muller N, Merwe C (2011). The potential of social media to influence socio-political change on the African Continent. Africa Institute of South Africa. Briefing 46.

|

|

|

|

Bossuroy T (2011). Ethnicity and Election Outcomes in Ghana. IRD Working Paper. Dauphine University. Paris.

|

|

|

|

Breen-Smith M (2012). Ashgate Companion to Political Violence. University of Surrey. Ashgate publishing.

|

|

|

|

Bucholtz M (2002). Youth and Cultural Practice. The Anthropologist. 31:525-52.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

CADA (2012). Election Violence in Ghana.

View

|

|

|

|

De Juan A (2012). Mapping Political Violence – The Approaches and Conceptual Challenges of Subnational Geospatial Analyses of Intrastate Conflict. GIGA Working Paper. 211: 4-29.

|

|

|

|

Dumouchel P (2012). Political Violence and Democracy. RitsIILCS_23.4pp.117-124DUMOUCHEL.pdf.

|

|

|

|

EC (2016a). Registered Political Parties.

View

|

|

EC (2016b). Political Parties Act.

View

|

|

|

|

Englert B (2008). Ambiguous Relationships: Youth, Popular Music and Politics in Contemporary Tanzania. Wiener Zeitschrift für kritische Afrikastudien. 14(8):71-96.

|

|

|

|

Enria L (2015). Love and Betrayal: The Political Economy of Youth Violence in Post-War Sierra Leone. J. Modern Afr. Stud. 53:637-660.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Erdmann G (2007). Party Research: Western European Bias and the 'African Labyrinth. in: M. Basedau, G. Erdmann, A. Mehler (eds.). Votes, Money and Violence Political Parties and Elections in Sub-Saharan Africa. South Africa. University of Kwazulu-Natal Press. pp. 34-64.

|

|

|

|

Everatt D (2000). From Urban Warrior to Market Segment?: Youth in South Africa 1994- 2000. Development Update. 3(2).

|

|

|

|

Gavin MD (2007). Africa's Restless Youth. Council on Foreign Relation. Curr. History 106(700):220-226.

|

|

|

|

Gyimah-Boadi E (2007). Political Parties, Elections and Patronage Random Thoughts on Neo Patrimonialism and African Democratization. in: M. Basedau, G. Erdmann, A. Mehler (eds.). Votes, Money and Violence Political Parties and Elections in Sub-Saharan Africa. South Africa. University of Kwazulu-Natal Press. pp. 21-33.

|

|

|

|

Hofmeister W, Grabow K (2011). Political Parties; Functions and Organizations in Democratic Societies. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung.

|

|

|

|

Honwana A (2013). Youth, Waithood, and Protest Movements in Africa. International African Institute. London.

|

|

|

|

IDEA (2006). Botswana Country: Report based on Research and Dialogue with Political Parties. EISA Report. Botswana laid out.pdf.

|

|

|

|

IDEA (2007). Political Parties in Africa: Challenges for Sustained Multiparty Democracy. Africa Regional Report.

|

|

|

|

Imoite J (2007). Youth participation in Kenyan politics: Challenges and opportunities. Panel presentation at the International conference on leadership and building state capacity: Youth and politics in conflict context. Woodrow Wilson International Centre for Visiting Scholars. May 16.

|

|

|

|

Kagwanja PM (2005). 'Power to Uhuru': Youth Identity and Generational Politics in Kenya's 2002 Elections. Afr. Affairs 105(418):51-75.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Kanyadudi CJO (2010). From the Wings to the Mainstream: The Role of Political Parties Youth Leagues in Democratization and Regional Integration in East Africa. FES. Nairobi.

|

|

|

|

Kanyinga K, Murimi JN (2002). The Role of Youth in Politics: The Social Praxis of Party Politics among the Urban Lumpen in Kenya. Afr. J. Sociol. 5(1):89-111.

|

|

|

|

Laakso L (2007). Insights into Electoral Violence in Africa. in: M. Basedau, G. Erdmann, A. Mehler (eds.). Votes, Money and Violence Political Parties and Elections in Sub-Saharan Africa. South Africa. University of Kwazulu-Natal Press. pp. 224-252.

|

|

|

|

Lindberg SI (2009). Democratization by Elections: A New Mode of Transition? Baltimore. Johns Hopkins University Press.

|

|

|

|

Maliki EA, Inokoba KP (2011). Youths, Electoral Violence and Democratic Consolidation in Nigeria: The Bayelsa State Experience. Anthropologist 13(3):217-225.

|

|

|

|

Mehler A (2007). Political Parties and Violence in Africa: Systematic Reflections against Empirical Background. In: M. Basedau, G. Erdmann, A. Mehler (eds.). Votes, Money and Violence Political Parties and Elections in Sub-Saharan Africa. South Africa. University of Kwazulu-Natal Press. pp. 194-223.

|

|

|

|

NPP Youth Wing Vandalizes Office - Destroys Kufuor's Portrait. General News of Monday, 22 March 2004,

View

|

|

|

|

Nti K (2016). Angry NDC youth set party office ablaze; burn down chairman's car.

View

|

|

|

|

Olaiya AT (2014). Youth and Ethnic Movements and their Impacts on Party Politics in ECOWAS Member States. Sage Open. pp. 1 -12.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Resnick D, Casale D (2014). Young Populations in Young Democracies: Generational Voting Behavior in sub-Saharan Africa. Democratization 21(6):1172-1194.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Shaba R (2007). State of Politics in Tanzania. Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung Country Reports. Tanzania.

|

|

|

|

Shayo R (2005). Parties and Political Development in Tanzania. EISA Research Report 24. Johannesburg. South Africa.

|

|

|

|

SID (2012). The Status of Governance in Kenya. A Baseline Survey Report. Nairobi-Kenya.

View

|

|

|

|

Sokupa T (n.d.). The ANC Youth League: Lost in the High Seas? afesis-corplan,

|

|

|

|

StarrFMOnline (2015). NDC's 'Azoka Boys' and NPP's 'Bolga Bull Dogs' on the Loose in Talensi.

View

|

|

|

|

Stewart F (2010). Horizontal inequalities in Kenya and the political disturbances of 2008: some implications for aid policy. Conflict, Security Dev. 10(1):133 -159.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

UNECA UNPY (2011). Youth in Africa: Dialogue and Mutual Understanding. Regional Overview. International Year of Youth.

View

|

|

|

|

UNESCO (n.d.). What do we mean by 'youth'?: Learning To Live Together.

View

|

|

|

|

United Nation Development Programme Report. 2006.

|

|

|

|

UNOCHA (2008). Fact-finding Mission to Kenya, 6-28 February. OHCHR Report. OCHA. Kenya Nairobi.

|

|

|

|

Van Gyampo RE (2012). The Youth and Political Ideology in Ghanaian Politics: The Case of the Fourth Republic. Afr. Dev. 37(2):137-165.

|

|

|

|

Wepundi M (2012). Political Conflict and Vulnerabilities Firearms and electoral violence in Kenya. Small Arms Survey. Issue Brief. 2.

|

|

|

|

Yang L (2008). Tranquility of Tanzania, a Nation Surrounded by Violence. UW-L Journal of Undergraduate Research. XI.

|