This study explains chief causes of covert and overt conflict between indigenous and non-indigenous ethnic groups of Metekel zone, since 1991. For the sake of convenience, however, particular emphasis is given to the conflict between Agew and Gumuz. The study employs relational ethnography research design. The data collected through in-depth interview, observation, informal conversation, and review of available documents is analysed thematically. The conflict between the two ethnic groups in the period is explained based on the assumption of horizontal and longitudinal deprivation. The paper demonstrates that coincidence of relative deprivation with ethnic line is creating favourable conditions for violent conflicts in the study area. In the period, Agews felt deprived of political resources in contrast to their history and Gumuz. On the other hand, though Gumuz are politically empowered, the socio-economic status of the people is hardly comparable with the Agew and other non-indigenous ethnic groups. The salience of ethnicity in the period has also been providing opportunity for elites to mobilize the mass for violence. But, the study argues the transformation of dormant conflicts into violence is determined by cost and benefit analysis of the action rather than by a mere mobilization of elites. Accordingly, in the period instigating violence seems persuasive for Gumuz than Agew. The finding implies that when the underlying conditions of relative deprivation are eliminated, the motive to use violence as a political instrument can also be minimized.

In contrast to others, most scholars attributed problems of instability in Africa to ethnic diversity (Abbink, 1997: 159). As such, states adopt different approaches regarding it. At one extreme, it is officially discouraged (Endrias, 2003: 2). In the majority of African states, ethnicity is refuted by the elites as backwardness and source of conflict (Neuberger, 1994). For example, Uganda disallows ethnic based parties – it champions de-ethnicized central state (Alem, 2003: 5). At the other end lies Ethiopia’s formula for managing ethnic diversity – ethnic federalism. Thus, Tronvol (2003:50) argued that “in the plural states of Africa, ethnicity has been blamed as the cause of conflicts in one context, and in another cited as the remedy to solve them.” Regarding Ethiopia, it is evident that its past history of ethnicity, ethnic relations and evolution of the state by itself is subject to polarized debates. When someone observes everyday political discourses in the country, contentions revolve around the following questions (Endrias, 2003: 3). Is Ethiopia three thousand years old or only one hundred? Have the Oromo and the Southern Peoples always been members of Ethiopian society or were they joined to Ethiopia through invasion and conquest in the nineteenth century? Nevertheless, everyone agrees that Ethiopia hosts a plurality of ethnic groups. Thus, disagreement is over whether or not ethnic differences and relations had been problematic in Ethiopian history that seeks a new political order (Endrias, 2003: 3).

To this end, with the coming of Ethiopian People Democratic Front (EPRDF) to political power in 1991, ethnic federalism becomes the principal institutional mechanism of Ethiopia to accommodate the aspiration of ethnic groups and as a panacea to past intra state conflicts. So as to accomplish this, the country is divided into nine ethnic based regional states. Possible claims of ethnic groups are further reinforced by the constitution through guarantying them ‘unconditional right’ for secession (Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (FDRE), 1995: 39). Ethiopia has thus embarked upon unprecedented experiment to the problems of ethnic heterogeneity (Abbink, 1997; Alemante, 2003; Endrias, 2003). However, prominent scholars on the subject argue that despite such a strange marriage of ethnicity and federalism for the above reasons, inter-ethnic conflicts have become more frequent since then than before (e.g Tronvol, 2003; Wondwosen and Zahorik, 2008; Asnake, 2013). Asnake (2013: 7) noted, “the federal restructuring of Ethiopia, even if it was aimed at finding a ‘resolution’ to ethnic conflicts, led to the changing arenas of conflicts by decentralising them and also generated new localised interethnic conflicts”. Thus, through an interdisciplinary approach this study explores the discouraging outcomes of ethnic federalism on interethnic relations, taking Agew and Gumuz in Metekel Zone as cases of the study. With ethnic federalism as state policy, and relative deprivation as explanation of ethnic disputes, the paper investigates dynamics of inter-ethnic conflicts in Metekel Zone.

Agew and Gumuz are neighbouring ethnic groups inhabiting north-western Ethiopia (the former Agew midir and Metekel Awrajas of Gojjam province). The two groups have long history of interaction characterized by both hostility and friendship. Their interaction traced back to time of antiquity (Teferi, 2014: 8). Nevertheless, the history of relations between the two groups was characterized by dichotomization than integration (Teferi, 2014: 17). The pattern of interactions particularly in the study area (Metekel) had been patron – client that was comparable with Hutu – Tutsi relationships (Taddesse, 1988a: 14 and Tsega, 2006: 105). During the imperial regime, local Agew chiefs were empowered by the central government of Ethiopia for intimate supervision of the resource and people of Gumuz, with the title of Agew Azaz (Teferi, 2014: 8). For example, Agew governor, Zeleqe Liqu (1905-1935) was assigned by Ras Haylu of Gojjam (son of Tekle Haymanot) to monitor areas of Tumha, Balaya and Dangur until Italian invasion (Tsega, 2006: 84). It also seems that in the post liberation period the active role of local Agew chiefs is almost unchanged until the recent political developments of the country. However, the studies indicate that though Agew chiefs were hostile to Gumuz, ordinary people had friendly relations for long periods of time. The Gumuz speak Agewigna, business transactions were carried out in Agewgna, and they were sharing the same forest for hunting (Ruibal et al., 2006). The resettlement program of the past regimes further consolidated their relations . For instance, Teferi (2014: 22-23) indicated that Gumuz were sided with Agew during violent conflicts between Agew and Wolloye Amhara settlers.

But, with the new government’s concession of full autonomy to Gumuz, things have begun to take another direction. The Gumuz makes no distinction between Agew and Amhara, and Agews are mistreated in land and other political rights. Grievances from both groups lead to violent personal and group conflicts. Among others, a long term structural conflict around Manjari can be mentioned (Ruibal et al., 2006). Therefore, the underlying factors behind these changes shall be investigated. Above all, in most studies, Agews of Metekel are treated either as Amhara or highlanders due to cultural and religious similarities. However, it is misleading; for example, while Alemayehu (2015) claimed that since 1975 the relation shifted from conflict to peaceful co -existence, Asnake (2013: 220) mentioned violent conflicts of Mentawuha in the immediate years of federalization. Empirically, many Agews have also been expelled from the region and mistreated by Gumuz in 2012/13. Furthermore, conflict with settler Amhara is attributable to resource competition and cultural reasons beginning from the time of their first arrival. In the past, these are too far to explain the case of Agews and Gumuz. As Dessalegn (1988: 131) notes, “for a generation or more the Begga [Gumuz] had amicable or at least tolerant relations with Agau [Agew] who live on the higher attitudes and with whom they trade....” Thus, if resource has been the case, the question is why it appeared being an issue only in post federal period. So, to understand dynamics of ethnic conflicts in Metekel, the case of Agew and Gumuz deserves a separate study.

In other studies, Agews in Metekel are misleadingly treated together with Agews in Awi zone (e.g. Desalegn, 2009). But, it is problematic because particularly in the post 1991 period the two sub groups of Agew exist in different political contexts. As such, the interaction of Agew in Metekel and Gumuz is scantly studied. As Eriksen (2002: 121) indicates, the political context of the relational space has important role in shaping ethnic interactions and conflicts. Thus, in studying ethnic conflicts, the case of Agew in Metekel needs its own study. Hence, to have a complete picture of the Agew-Gumuz interaction and conflict one needs to look at the impacts of radical state restructuring of the post -1991 period and the resulting salience of ethnicity in the political and social arenas of the country. The studies made so far are general as well as historical and hence give a very limited account of the contemporary Agew-Gumuz relations particularly in Metekel. As such, there exists a knowledge lacuna. Accordingly, this study shall mean to contribute its own share in filling the existing knowledge gap on the aforementioned case. The material in the study depends on the field work conducted from December to February 2015/16.

Setting of the study area

Metekel is a vast territory in northwest Ethiopia from the border of Sudan to the north of Abbay River (Blue Nile). The word Metekel is derived from one of the seven Agew clans, awi lagneta . It is bordered on the north by North Gonder Zone and in the east by Awi zone. To the South and South west, it is bordered with Khamashi Zone, while to the west it adjoins with the Sudan. In the pre-1991 state structure, Metekel region, known as Metekel Awraja, was part of Gojjam province. At present, however, although it kept its former district with some rearrangements, it has become a zone under BGRS. Some parts of the former district of Guangua with the capital, Chagni, and a portion of Dibati districts are included to Awi Zone of ANRS. Since the end of 2000, Gilgelbeles town, which is 546 km away from Addis Ababa, is the capital of the Zone.The name Metekel, therefore, is used in the study to refer districts included after the area is designed as administrative zone in 1991. These are Bullen, Dangur, Dibate, Guba, Mandura, Wembera and Pawi. The major ethnic groups inhabited the area are Gumuz (36.78%), Shinasha (21.6%), Agew (11.65%), Amhara (17.39%) and Oromo (11.09) (CSA, 2007). There are also other folk ethnic divisions which are relevant for the study such as qey and tikur , nebar (early inhabitant) and mete (recent migrant), highlanders and lowlanders, yekilil balebet (son of soil) and leloch hizboch (non titular). In this study, however special emphasis is given for Gumuz and Agew.

Various researchers insisted that Gumuz are welcoming for the Agew in contrast to other people such as Amhara (e.g Desalegn, 1988: 131; Gebre, 2003; Ruibal et al., 2006; Desalegn, 2010: 77). But, the data from the field work revealed that the Gumuz are now equally hostile for Agew (particularly for immigrants) as well. Accordingly, the period witnessed new forms of conflict between the two groups from boundary conflict to forceful eviction of the Agew from the ‘Gumuz country’. Various causes of conflict are mentioned by observers, political parties, government bodies, and mass media even from groups themselves particularly for 2012/13 event . Some of them attributed it to resource competition. But, if it has been the cause, why did it appear only in post 1991? For instance, Dessalegn (1988: 131) reported that Gumuz had welcoming environment for the Agew with whom they trade. And land had not been an issue in the relation of the two groups . Others blame the political policy of the state, ethnic federalism, for all problems regarding ethnicity and ethnic relations. However, studies have demonstrated tangible positive results on the relation of the two groups in the period . Thus, ethnic federalism is not the only reason to be always blamed. On their part, government officials from Zone and Districts are blaming misconduct of non-indigenous ethnic groups and instigation of neighbouring regional states. In general, informants and researchers who look at the perspective of non-owner groups blame ethnic federalism (based on the local context) and what they called ‘uncivilized culture’ of Gumuz. On the other side, in the perspective of indigenous ethnic groups, improper behaviour of non-owner groups and instigation of neighbouring regional states are blameworthy.

However, puzzling out the existing situation in the area needs to look in many directions – past and present. The data from the field work indicates that conflicts in the area particularly between Agew and Gumuz are accumulative results of historical, social and political context. The chief causes that emerged from contradictory feelings and sentiments to the existing political system sprang from past and existing positions of each group. All informants of this study unanimously mentioned that ‘jealousy’ is a fundamental cause of conflict between the two groups in particular and, indigenous and non-indigenous ethnic groups in general. Gumuz insists to say ‘someone from anywhere is coming to our country and becomes richer while we are living in a worst situation than what our ancestors used to live’. The Agew, on their part, are ‘jealous’ on the political position of Gumuz in the area. All other factors mentioned are either causes or results of this feeling. Among others, immigration, land encroachment, land degradation, discrimination, exclusion, looting crops and properties, disagreement in the time of harvest sharing, and disputes on land leasing arrangements are the major. Oxford word power dictionary defined Jealous as “feeling angry or sad because you want to be like somebody else or because you want what somebody has.” Jealousy, therefore, describes the feeling of being angry or upset because something you need or deserve is in others hand. The feeling develops when someone compares his position with another. So, in the case of Gumuz in contrast to Agew and other non-titular ethnic groups, they felt as economically deprived. Similarly, the Agew felt as deprived off in their political position. Transactive approach, from which relative deprivation has extended, claims that ethnic conflict is the result of feelings and sentiments in which members of a particular group develop as they interact and compare themselves with other ethnic groups (Hyden, 2006). The feeling might be negative or positive – inferiority or superiority. The negative one will transform into the feeling of relative deprivation.

Relative deprivation

Nafzige and Auvienen as cited in Freeman (2005: 5) have defined relative deprivation as ‘people feel deprived of something they had, but subsequently lost or when others have gained relative to them.’ Thus, deprivation is a relational concept. ‘X’ is deprived off relative to ‘Y’ or ‘Y’ is worth off relative to ‘X’. X and Y are either individuals or groups based on ethnicity, gender, or interest. Systematic exclusion of one group from another because of different group identity can be a cause or manifestation of relative group deprivation. Exclusion is denial of access to or non-participation of individual members of ethnic group from key activities of a society for reasons beyond their control, though they would like to participate (Dertwinkel, 2008: 7). A key activity of society refers to political engagement, cultural interaction and economic participation. Freeman argues, “The overlapping of ethnic divisions and patterns of relative deprivation created an environment primed for conflict” (Freeman, 2005:7). Let us discuss in the context of Agew and Gumuz.

Political deprivation of Agew

Historically, the Agew in Metekel were politically dominant ethnic groups. Tadesse (1988a: 14) and Tsega (2006: 105) described the historical Agew-Gumuz relation as patron-client which was equivalent with the pattern of Hutu-Tutsi relations in Rwanda. Nevertheless, the post 1991 political arrangement reversed the pattern. Now Agews in Metekel are subordinate on Gumuz which are defined as ‘owners’ of the region. Agews who were long favoured by the past regimes of Ethiopia lost their political dominance for Gumuz. Consequently, the change brought many grievances on the side of Agew and further claims from Gumuz. These grievances and claims are directly or indirectly linked to the following issues.

a) Territorial re-arrangement: The post 1991 political development brought rearrangement of territories in different parts of Ethiopia. It divides the same ethnic groups, while merging distinct ethnic groups into one administrative unit. The territorial re-arrangement is cited as major and aggravating cause of ethnic conflicts in the period such as Guji and Gedeo, Afar and Issa, Borana and Gari (Asnake, 2004: 62-64). There was also a dispute between ANRS and BGRS over boundary which is predominantly inhabited by Gumuz and Agew (Asnake, 2013). But, here, it is imperative to discuss how the new territorial arrangement brought feeling of deprivation among the Agew of Metekel. During the past regimes, the territory of Agew and Gumuz was under one administrative province, Gojjam province. But, the new territorial restructuring, following the downfall of the military regime changed the status quo. The two groups obtained different administrative units in their name. Accordingly, the Agew are represented by Awi nationality zone (in ANRS) and Gumuz by BGRS. However, considerable number of Agews remained under BGRS. Agews in BGRS is more than Agews in Amhara region in terms of their share from total population of their respective regional states. Informants from both groups agreed that Agews are deeply dissatisfied with the new arrangement and felt that they are being dominated by the despised group Gumuz and Shinasha, and separated from their ethnic fellows – Agews in Awi zone of ANRS.

All Agew informants reflect their discontent of being dominated by Gumuz and Shinasha, whom they represent as ‘culturally inferior, uneducated and capable only for slavery’. They also felt that they are politically deprived in contrast to their past history. In contrast, Agews of Awi Zone in ANRS seemed to have been enjoying their constitutional right – right to self-administration. In Awi zone, Agew is language of instruction for primary school, there is Agewigna radio program and they have a special nationality zone. Accordingly, Agews of Metekel demand for self-government, to exercise their language, culture and traditions as enshrined in Art 39 of FDRE constitution. According to Agew informants the space in Metekel is excluding them from the aforementioned constitutional rights. The Gumuz are denying their right to exercise their cultural rights . The dissatisfaction leads Agews to frequently ask for either political empowerment or territorial integration with Awi zone. In response, informants reported that local Gumuz authorities are intimidating leaders for such move. On the other hand, for Gumuz, quests of Agew are considered as ambitions to control productive resources or a move to bring back the past pattern of relation between them – Agew dominance. Moreover, the Gumuz elites blame political elites of Awi zone as instigators of the move.

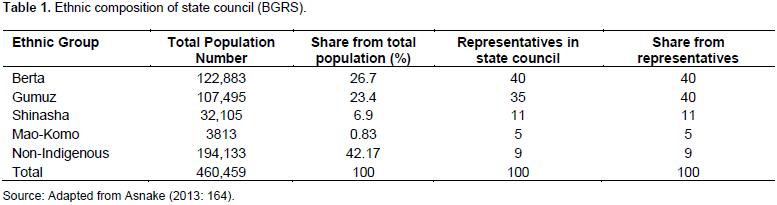

b) Political dichotomization and exclusion: The new political arrangement has got polarized responses from ethnic groups of the area. Past marginalized ethnic groups such as Gumuz warmly welcomed it with additional claims (for further exclusion of non-titular ethnic groups) (Asnake, 2013). On the other hand, non-indigenous ethnic groups like Agew are deeply dissatisfied; they felt as they are considered secondary citizens. Moreover, political categorization of ethnic groups into owners and non-owners leads to political exclusion. Empirically, the right of non-indigenous ethnic groups of BGRS is very limited. The revised regional constitution of 2002 was declared to establish five tiers of government, region, nationality administration, District and Kebele. On this, nothing is mentioned on how the arrangement could accommodate the political interest of non-indigenous ethnic groups. The constitution of the regional state has also exclusively guaranteed unconditional right of self-determination up to secession for indigenous ethnic groups of the regional state (Benishangul Gumuz Regional State (BGRS), 2002: 39). At regional level, members of state council are people of the region as a whole, with special right extended to Mao and Komo (BGRS, 2002: 48). Unlike to non-indigenous ethnic groups, indigenous ethnic groups have the right to establish their own nationality councils (BGRS, Proclamation no. 73/2000). However, in contrast to their population size, non-indigenous ethnic groups are marginalized from fair political participation. Table 1 shows variations in political representations of indigenous and non-indigenous ethnic groups in the state council.

According to official informants, out of 9 non indigenous representatives in the state council Agews have only one representative. In addition, all political executive offices at regional and Zonal level are controlled and shared by indigenous ethnic groups based on their population number. For example, in Metekel zone all members of cabinet council are exclusively from Gumuz and Shinasha (Simeneh, 2010: 86). Moreover, the electoral law of the FDRE stated that the people who are not eligible to local language of electoral district where they are competing cannot become candidates (Asnake, 2013). Thus, non-indigenous groups, particularly recent immigrants are not eligible to local languages. Thus, the law makes non indigenous ethnic groups handicap to exercise their constitutional right – the right to elect and to be elected. As Asnake (2013: 169) notes, “they could vote but not run office.” Freeman (2005: 6) noted that when a group of individuals are excluded from the political process or disadvantaged in some manner, they are being deprived of their political rights. As Tsega (2006: 121) quotes, ‘Exclusion or perceived exclusion from political process for reasons of personal, ethnic or value difference, lack of socio political unity, lack of genuine access to national institution of governance [...] constitutes major socio-political causes of conflicts in Africa.’ Hence, political exclusion of non-indigenous ethnic groups is another cause of inter-ethnic conflict in Metekel zone, since 1991. Different from other non-indigenous ethnic groups, Agews in Metekel claim as they deserve the right to be indigenous people of the region. For example, they proposed to have at least Dangur special district, and to be recognized as indigenous ethnic groups for historical reasons. Informants of the study reported that they have appealed to house of federation, but accessing the data is not successful.To sum up, in post 1991 period Agews in Metekel felt as they are politically deprived longitudinally, in contrast to their past history and horizontally in contrast to other referent groups such as Gumuz and Agew of Awi zone. This is one of the chief causes in hostile relations between the two groups.

Socio-economic deprivation

Tsega (2006:122) notes, “The main causes of conflicts between groups (in Metekel) include the unresolved nature of socio-economic issues which are further complicated by ethnic antagonism.” The field work revealed that both groups have feelings of deprivation to each other. Grievances of Agew are related to denial of access to productive resources and discrimination in job opportunities. Similarly, Gumuz felt that they are systematically excluded from economic participation.

i) Economic deprivation of Agew - Exclusion from means of production: Rothild and Olornusola as quoted in Tsega (2006: 123) argued ‘In the agricultural societies of Africa, particularly where the population is dense, the penetration of money economy give rise to intense competition for land’. Accordingly, following the 1991 political change, economic grievances of Agew in Metekel are related to exclusion from sharing productive resources such as Land. It is observed that population number and family size of Agew is increasing from year to year. However, the productivity of land is also deteriorating and they remained with the land size what they had before 1991. In this period, the interest of the Agew to search new fertile land is very difficult, since they are once labelled as non-owner ethnic groups of the region. Agew informants reported that government officials are not even interested in allowing Agew individuals lease a land from government formally. In contrast, Gumuz are enjoying their moral and legal rights over fertile lowlands. Therefore, the Agew are expected to arrange lease or sharecropping agreements with Gumuz to have access for new fertile lands. The Agew claim the arrangement is unfair while the Gumuz blame the Agew for their mischief during partition of the harvest.

Another grievance of Agew in Metekel is regarding job and education opportunities. Since, the federal government sets preferential treatment for historically marginalized ethnic groups, Gumuz and other indigenous ethnic groups have priority in civil service personnel and educational opportunities which came under the regional government. Agews in Dangur district are also blaming the regional government for excluding them from access to social services and infrastructures. Areas where schools and health care institutions are built is discriminatory against the Agew people. For instance, Agew informants claim, though a highway from Mambuk to Belaya (Agew dominated area) is started before five years, it is still intentionally unfinished. In understanding these discriminations, according to Agew informants, ADA (Awi Development Association) from Awi zone is attempting to solve the problem. For example, it has constructed one secondary school in Hankesha Gebrel, a place where predominantly inhabited by Agew. According to informants the association is now trying to finish the highway.

ii) Socio-economic deprivation of Gumuz: Though ethnic federalism has politically empowered Gumuz, as the field work reveals changes in their socio-economic life has not been promising. In terms of standard of living, level of income and saving, Agew and other non-indigenous ethnic groups are by far better than Gumuz. There is serious socio-economic inequality between members of the two categories. Informants from both ethnic groups agreed that the economic inequality is one source of jealousy for Gumuz. The Gumuz felt that they are deprived off relative to the Agew (and other non-indigenous), though politically the former are advantaged groups. This is a major cause of frequent attempts of Gumuz and Shinasha to forcefully expel immigrant Agew and Amhara from Metekel in the last two decades. The Gumuz felt that they are systematically marginalized in their ‘country’. Factors ranged from past marginalization of Gumuz to policy disasters of past and existing government have their own share in creating or exacerbating social and economic deprivation of Gumuz. Accordingly, the socio-economic deprivation of Gumuz is emanated from the following multifaceted factors.

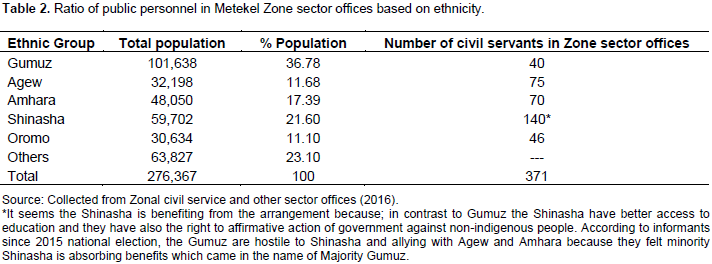

a) Historically deprived ethnic group: Studies indicate that the incorporation of Agew into medieval Ethiopia brought Agew dominance over Metekel and Gumuz (Taddesse, 1988b). Gumuz were subjects of slave raiding and abusive taxation system of Agew rulers for long periods of history. The Gumuz country has been land of hunting and source of lucrative trade items (Tsega, 2006; Taddesse, 1988b). Memory and narration of past distasteful history among the Gumuz is mentioned as immediate cause of personal conflicts in the area. Agew informants exposed that both common people and elites of Gumuz are obsessed to say, “you (Agew) had tortured and enslaved the Gumuz in the past, but now it is our (Gumuzs’) turn.” As Wolf (2006: 69) argues, intentional narration of problematic inter group history is one source of ethnic hostility. Moreover, the trickledown effect of historical marginalization of Gumuz is manifested on the existing socio-economic inequality between groups. The impact of historical marginalization of Gumuz is at least evident in their share of civil service personnel, challenges to access to infrastructure, and less economic participation (market integration). In the early years of federalism, BGRS has absorbed educated manpower from neighbouring people, because indigenous ethnic groups were not capable of stuffing the required civil service personnel in the region. Official sources reported that 80% of personnel at regional government sectors are non-indigenous ethnic groups (Mesfin, 2011: 206). It is more likely associated with past exclusion of Gumuz (other owner ethnic groups) from access to education (Table 2).

Moreover, as Woldesellassie (2004: 271) observed, most of the Gumuz are employed as security guards and office messengers due to low level of education to meet requirements for professional positions. The remaining Gumuz are those in political positions, since non indigenous ethnic groups are totally excluded from political participation. Officials reported that stuffing indigenous (with political position) over non indigenous (civil servant) has also brought occasional disputes around office. Government official informants also emphasized that the dispersed settlement of Gumuz in the inhospitable lowlands is also a challenge to access of social services and infrastructure. Regarding the existing settlement pattern of Gumuz, Ruibal et al. (2006) argued that it is the result of past exploitation by highland neighbours. The Gumuz is predominantly dispersedly populated in isolated malaria infested lowland rural areas. In contrast, majority of the Agew and other non-indigenous people are town dwellers. As Tsega (2006: 125) stated, the absence of roads, schools, clinics, among others, contributed to their backwardness and triggered friction between those who were able to be educated, urban based [Agew and other non-indigenous] and those limited to malaria infested lowlands [Gumuz]. Moreover, the past system left the Gumuz with fewer skills of production for market economy. They still have less skill to trade or to plough for surplus. As the field work revealed, Gumuz women came to market with primary commodities which have less monetary value.

On the other hand, the Agew are good agriculturalists, good traders, and good service providers. Regarding the integration of historical marginalized minority groups to the main economy, Kanbur (2007: 3) argues, “If markets were competitive, with market power evenly distributed, then integration into market should increase income earning opportunities for those previously excluded, and reduce process as well as outcome marginalization” (Kanbur, 2007: 3). However, Kanbur (2007: 2) further stated that the end of market integration is determined by concentration of market power. It means, in monopolized market structure where those at the weaker end lose out from market though they are integrated. In Metekel, the market power is already concentrated on previously favoured groups, Agew (and non-owners). Thus, the recent integration of Gumuz into this competitive market often ended up with negative outcome for them. Hence, the existing socio-economic variations between the two groups are emanated from their respective positions of the past. As the coming sections elaborated more, interventions on historically marginalized groups such as Gumuz should made with great caution.

b) Immigration: Land encroachment and resource degradation: The history of Metekel area has been characterized by both formal and informal influx of people from highland areas. Beginning from 1950s, people are migrating from drought prone areas of northern Ethiopia to Metekel (Teferi, 2014). The most remembered influx of people to the area occurred during the 1980s, sponsored by the Derg regime. According to sources, the program had a proposal to settle people even more than the total population number of host communities in Metekel Awraja (Dessalegn, 1988). Results from various studies reveal that the program brought adverse socio economic impact on the host community particularly on Gumuz. For example, Gebre (2003: 59) noted that Gumuz people around the settlement sites were subject to economical, political and psychological deprivation. Gebre (2003: 60) further stated that “the 1980s resettlement in Ethiopia resulted in land dispossession, loss of life, home destruction, decline of access to common resources, marginalization, erosion of customary laws and periodic insecurity for the Gumuz.” In post 1991 Ethiopia, the food security strategy of FDRE states that resettlement program must be inter regional (Desalegn, 2014).

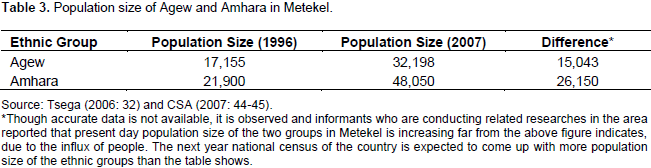

But, empirically, it is reported that substantial number of self-initiated people, particularly the Agew are immigrating to Gumuz country. Former settled families are also attracting their relatives from Wolo and Tigray. This means, Metekel remains a destination for people from highland areas where land is scarce and infertile, and population number is high. It is indicated that since the 2006 land redistribution program in ANRS, Agews from Awi zone are constantly drifted to Mtekel Zone. They will join their early established relatives or get into informal agreements with Gumuz for access to land. Otherwise, they clear forests and began their cultivation. Recently, Kunfel Agews (lowlander Agew) from Jawi woreda of Awi Zone are also informally fled to BGRS For various reasons, migration of Agew from Awi zone to Metekel is increasing from time to time. Table 3 shows population size of Agew and Amhara in two consecutive national census of Ethiopia. Table 3 shows that the population size of the two ethnic groups is double the number it was before 10 years. This constant informal influx of Agew (and others) to Metekel is exacerbating socio-economic inequality among the two categories of people. Above all, it brought the following negative outcomes on Gumuz people.

Land encroachment

Gumuz informants reported that newcomers have systematically encroached the Gumuz land through cheating, forming fake social bonds and forceful displacement. An informant from cabinet members of Mandura district stated that “in present day, Gumuz of Manjerri are left without land, because Agew and Amhara systematically alienated them just by a bottle of Areqe (local liquor)”. Another mechanism of land possession of newcomers is through cheating corrupt kebele officials. Some kebele officials allow newcomers to settle by giving false dated identity cards. For example, if the individual comes to the area in this year (2008 E.c) the card is prepared as he is resident to the area since 1990s E.c. Sadly, Gumuz informants reported that newcomers also clear forests and begin their cultivation because they presume the area is ‘no man’s land’. Also, newcomers are not familiar to communal ownership of natural resources and shifting cultivation practice of the Gumuz. Tenancy arrangements mainly land renting and sharecropping are other ways of acquiring the Gumuz land by highlander Agew. Though majority of informants mentioned it as the new pattern of positive relations between the two groups based on the principle of equality, studies revealed their negative outcomes. According to Gebre (2003: 58), this is for the following reasons. First, agreements are informal which lack legal recognition where disagreements cannot be solved formally. Second, newcomers are interested in paying taxes directly to the government so as to secure their possession of land formally. This systematically alienates the Gumuz from their land. Gumuz informants also blamed less commitment of new comers for protection of land fertility.

The mass influx of people to Metekel has also been shifting communal ownership of land holding system to private holding system. Consequently, Gumuz lost security of at least their traditional usufruct right over land. In the last two decades, unprecedented land competition has been witnessed even among the Gumuz. Gebre (2003: 56) notes:

Gumuz communities became reluctant to share land with other Gumuz. For example, in 1997, leaders of Manjeri asked another Gumuz village in Mambuk district to accommodate 20 land poor households from Manjeri. The village council in Mambuk rejected the request because of increased land shortage in the area.

Gumuz are excessively dependent on nature for livelihood. It is said that the influx of people to Metekel introduced ‘private’ ownership of land in the place of communal ownership of natural resources. Moreover, natural resources are threatened by forest clearance of new comers. Thus, the mass influx of newcomers to the area is challenging customary food security of the Gumuz.

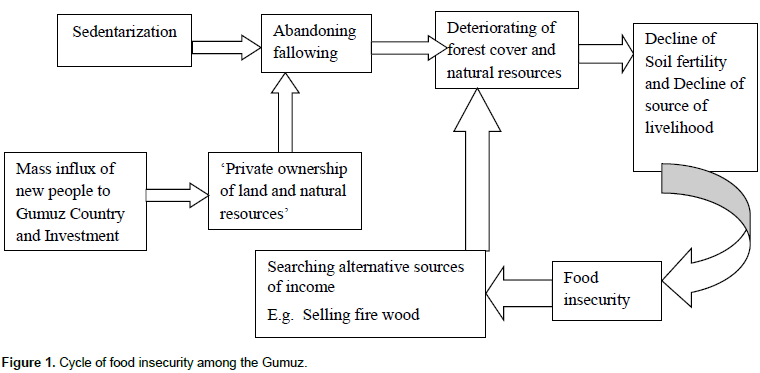

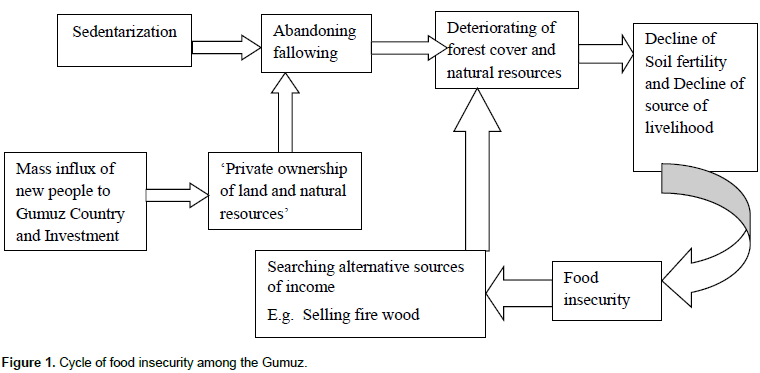

Frequent food insecurity among the Gumuz put pressure on them to search new alternatives of livelihood such as selling firewood that was shameful activity in old days. To its worst impact, cutting trees for firewood leads to clearance of forests. Clearance of forests is the cause of land degradation and productivity which threatens their survival. The vicious circle of food insecurity problem among the Gumuz is described in Figure 1. To sum up, migration into Metekel is complicating the life of the host community, making survival challenging. The assumption of social Darwinism best explains the case, ‘as increasing population is normally out growing its food supply. This would result in the starvation of the weaker’ (Anupkumar, nd: 5). Gumuz informants claimed that “non-indigenous people are systematically exploiting their resources and the way they live is hardly comparable with them and their ancestors.”

A) Federal and Regional Rural-Development Policies: Another factor which aggravates socio-economic inequality among the two categories of people is rural development policies of the government. Government policies including the existing one are usually based on false presumptions regarding Metekel and the Gumuz. Consequently, the intervention ended with adverse effects on the people (Gumuz). For example, the resettlement program of the 1980s was the result of presuming lowland areas of Metekel as ‘no man’s land’ with agricultural potential (Gebre, 2003: 50). Dessalegn (1988: 122) also notes, the Dergue, misperceived the socio-economic system of the Gumuz as being counter revolutionary proposed massive resettlement program into Metekel as a solution. Nevertheless, the misfortunes happened on socio-economic lives of Gumuz were deep. Similarly, the existing rural development policy of Ethiopia categorized the country into three agro ecological zones:

1) The east and south eastern arid land where the main livelihood is cattle herding.

2) The west lowlands, where there are large areas of uncultivated land and a small population.

3) The highlands, which are ideal for farming, but farm land is limited and rapidly eroded and where population density is high (Mesfin, 2011: 224).

From the above agro ecological zones, Metekel is located in the second category. But, the policy does not consider the farming practice and livelihood basis of local people; it considers only the population size and fertility of the land. The policy encourages establishment of large commercial farms on the basis of attracting cheap labour from neighbouring highland areas. However, it does not include that from which local people could benefit. Moreover, for Gumuz, lowland areas of Metekel are not only sources of livelihood but also a matter of identity. The data released from investment office of BGRS to publicize the agricultural potential of Metekel indicates that total area of the region is 50,380 km2 where 911,876 ha is cultivable and 265,097 ha uncultivated (Desalegn, 2010). However, the land said to be uncultivated is the area inhabited by shifting cultivators of Gumuz and other indigenous ethnic groups. Moreover, Mesfin (2011) reported that the regional government has recently transferred administration of 1.2 million hectares of uncultivated land for federal government to attract foreign investors in Agriculture and mining sector. As a result, investors are flooding to Metekel. Job opportunities from investments and government development projects are another cause for spontaneous migration of people to the Gumuz country.

It is reported that investment projects are also exacerbating socio-economic variations between the two categories of people. Projects are alienating Gumuz from their land, attracting people from neighbouring regions, and deteriorating of forest cover and sources of livelihood. In contrast, Agew and other newcomers are living better life; they are either investors or employees in investment enterprises. The Gumuz cannot compete with highlanders because the first lacks economic capacity and is perceived to lack skills/techniques in which the projects need. So, the Gumuz felt that ‘others’ are better off in the Gumuz country at the expense of their advantage. Another policy disaster sprang from endured mind set up about the Gumuz sedentarization policy of the regional government, since 1999. Government officials informed that the aim of sedentarization is for better socioeconomic life of shifting cultivators. Accordingly, Gumuz are expected to abandon shifting cultivation and become plough cultivators. Though it needs more investigation, according to studies conducted so far, the policy is more likely disastrous for the life of Gumuz than beneficial (Dessalegn, 1988; Gebre, 2003). This is because shifting cultivation in Metekel is more environment friendly than plough cultivation. Soil type of Metekel could lose its fertility more by plough cultivation than shifting, since the former demands abandoning fallowing practice which is an essential part of the latter. Fallowing has been a technique to preserve land fertility. Dessalegn (1988: 130) noted:

The shifting system survived so far because it has been able to maintain a delicate balance between man and the environment. Although their technology is rudimentary, it is at the same time adapted to the existing soil conditions. The fine textured vertisoil found in most Begga [Gumuz] areas will be quickly damaged if farmed with the plough or the tractor.

Hence, policies of government with immigration are highly threatening the food security of Gumuz in the following way as shown in Figure 1. Still today, the regional government lacks clear land holding policy based on the context of people in the regional state. Government officials reported that the land in the region is administered with FDRE constitution and federal land policy. In Ethiopia land is public property and administered by the government which could not be sold or bequeathed (FDRE, 1995: 40). According to the government of Ethiopia, the objective of making land public property is to protect the identity of historically marginalized groups such as Gumuz. However, in the case of Gumuz, the reality is to the reverse at least for the following two reasons. Primarily, Ethiopia hosts diverse ethnic groups, and groups have different customary land holding system. For instance, the two neighbouring groups, Agew and Gumuz have different conceptions on property of land. To the Gumuz, land and natural resources are communal and sacred properties where their deities and ancestors are found. On the other hand, Agews considered land as private property and source of prestige.

Thus, to exercise right to self-administration, each ethnic group must be allowed to administer its land in accordance to its custom. But, in the existing system, administration of land and other natural resources is given for federal government (FDRE, 1995: 51) and it is defined as public property (FDRE, 1995: 40). So, the system marginalized ethnic minorities from administering their land in line with their traditional land tenure systems. Secondly, recently government of Ethiopia introduced lease arrangement for 99 years to attract foreign investors. Lands reserved for the arrangement predominantly exist in areas inhabited by shifting cultivators such as Gumuz. It means the system could still not protect minorities against land encroachment and grabbing. Hence, though the 1991 political change empowered Gumuz politically, a lot remains to be done on economic self-determination. To borrow Gebre’s statement, “in Ethiopia, land of shifting cultivators continue to be appropriated because their customary rights are not recognized. But, as long as people practice shifting cultivation as a way of life, it should be legally acknowledged” (Gebre, 2003: 60).

B) Social exclusion - Stereotypes: Max Waber explained that social exclusion is ‘an attempt of one status group to secure for itself a privileged position at the expense of another group through a process of subordination (Dertwinkel, 2008: 8). Accordingly, for the Agew, Gumuz were despised groups only capable for slavery which could be raided and sold by Agew chiefs. The Agew and other highlanders still insisted to call the Gumuz by derogative names such as Shanqila, Barya, and Gagri. The Gumuz are considered inferior people in all aspects of life. In such a way, they become isolated people in lowland areas which are far from modern infrastructure. Agews and other non-indigenous ethnic groups considered Gumuz as uncivilized people; as their culture is not equivalent to their Christian culture. Therefore, Gumuz has been suffering from cultural discrimination and enslavement. Cultural aspect of social exclusion is manifested in marginalization from cultural interaction (Dertwinkel, 2008: 9).

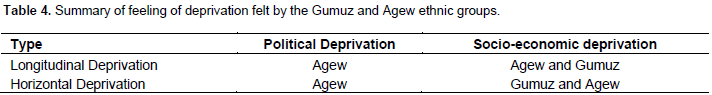

For instance, Gumuz were/or not considered to be proper marriage partners for majority of the Agew. These past stereotypes are still evident in the day to day interaction of people. A conservative Agew informant from Dangur district said “how you hate someone who is pagan, undereducated and black to argue against you, and to have marriage alliance with you. The long held Gumuz hostility to Agew slave raiders breeds violent cultural practices among the Gumuz community. Agew informants reported that killing non Gumuz for cultural reasons is increasing from time to time. Mesfin (2011) has also reported that police officers in Mandura and Dibati district are influenced by traditional leaders which hinder them from discharging expected responsibilities in controlling crimes. In general, from the discussion it can be concluded that the fundamental cause of conflict between Gumuz and Agew is feeling of relative deprivation. Gumuz felt deprived socio economically both horizontally and longitudinally whereas the Agew felt deprived of horizontally and longitudinally on politics and ownership of economic resources (Table 4).

Mobilization

Decline in key activities of the society in contrast to other referent groups engenders deeper resentment. As endured, it can be transformed into violent action. Violence is one means of showing deep feelings of anger and dissatisfaction on the existing perceived or actual unjust disparity. Nevertheless, according to Freeman, deprivation would not solely drive individuals for violent action. It needs competency of elites to mobilize members of the group (Freeman, 2005: 9). The coincidence of ethnic line with relative deprivation provides an opportunity for mobilization. Though mobilization is not an easy task, its success is determined by various factors. The degree of ethnic diversity and the prowess of political leaders are two especially important elements in mobilization process (Freeman, 2005). In both extremely diverse and homogenous societies mobilization is very difficult. Medium range of ethnic heterogeneity gives opportunities for instigating the mass. In Metekel, the major ethnic groups are five. This number by itself is optimum, but, besides this, the regional constitution has classified people of the area into two; owner and non-owner. So, elites have the chance of manipulating this artificial ethnic line. For example, informants from both groups agreed that in the 2012/13 event, major instigators of Gumuz against Agew and Amhara were Shinasha elites.

Moreover, the ideological framework of the government makes ethnicity salient in social life of the state in general and the study area in particular. In post 1991 period, even village names are assigned based on ethnicity. For example, the researcher has observed that village names in Mambuk and Dibati are yeagew sefer (village of Agew), yegumuz sefer (Village of Gumuz), yeshinasha sefer (village of Shinasha), yedamot sefer (village of Damot Amhara) and the like. Informants from both towns indicated that this is the recent development, that is, another opportunity for mobilization. People are now socialized by the political framework of the state. Ethnicity becomes the predominant explanation to various things which went wrong. Thus, elites can distort it for their advantage though the fundamental factor of conflict is about economic and political issues. Past pattern of relationships among the two categories of people is another favourable environment for elites. Elites can intentionally interpret or misinterpret the history so as to create mob.

Rationalization

As stated before, coincidence of relative deprivation with ethnic line creates suitable environment for strife, and mobilization only facilitates it. But, it is not meaning violence is inherent. Human beings are rational animals; they use their rationality to determine best solutions for the problem. Freeman (2005:11) notes “the average human employs violent tactics because he/she understands it to be the best or only option.” The cost and benefits of violence is also reconsidered. Violence may be perceived as a mechanism to bring short and long term political and economic gains. On the other hand, death and economic destruction are among the costs of violent conflict (Collier and Hoeffler, 1998). Fear of death decreases as the possibility for success is high. Worrying about economic destruction is again determined by the existing economic position. For now, Gumuz non owner groups including Agew are future threats of their political dominance. Above all, the Gumuz have nothing to worry about economic looses because they are marginalized in contrast to Agew. And politically they are in dominant position which favours their likelihood of success. It means being able to expel non owner groups from the area allows them to secure and eliminate future threats to their political status and existing economic deprivation. On the other hand, Agew and other non-ethnic groups are experiencing longitudinal and horizontal decline in political power. But, the economic power is in their hand. Without political resources, success of non-owner groups is less likely. Moreover, from the violence, economical loss tilts towards them. The Agew are economically advantageous in Metekel. This is the reason for the return of majority of people to Metekel which were expelled in 2012/13. Moreover, the influx of people to Metekel keeps bringing positive demographic outcomes for non-owner communities to raise possible political questions. It means, in a peaceful and democratic way they can change the existing political position. As far as they have political power then they will have right to share productive resources. Thus, instigating violence is not the best option for Agew and other non-owner groups. Hence, the possibility of instigating violent conflict is more likely from the side of Gumuz (and other indigenous ethnic groups). The influx of migrants keeps deteriorating their economic livelihood. Informal immigration has not been controlled by formal institutions and the political tendency of non-owner groups keeps threatening their political position. Moreover, the possibility of success keeps coming to them. The data from the field work has also revealed that causalities in the period including the 2012/13 are always instigated by indigenous ethnic groups – Gumuz and Shinasha.