Interfaith dialogue is becoming a household name in our global society within the context of religious pluralism. Christians and Muslims are widely spread across the globe commanding almost a half of global population. Some Christians, particularly among some Pentecostals view Muslims with distrust, apprehension and rivalry. In Nairobi, Kenya, features of mistrust, disharmony, and intolerance among Pentecostal churches toward Muslims have been witnessed and vice versa. The study explored Christian-Muslim dialogue with particular reference to Pentecostal Christians and Muslims in Nairobi, Kenya. It examines Biblical and Qur’anic teaching on Christian-Muslim dialogue. Integrated Inclusivism Conceptual Model of interfaith dialogue is discussed showing how various areas of convergence and divergence work. Constructive Christian-Muslim dialogue should take into consideration integrated inclusivism ideals such as shared theological concepts and values, socio-political and economic dialogue and divergent theological concept. The paper recommends that Pentecostals Christians and Muslims should not ignore Biblical and Qur’anic teachings. Overarching interfaith hindrances should be reduced in order to talk to each other in a respectful way. In conclusion, interfaith dialogue is the solutions for effective dialogue between Muslims and Pentecostal Christians in Nairobi, Kenya.

Christian and Muslim dialogue is becoming a common phenomenon in some parts of the global society. The basis for Christian-Muslim dialogue is that Christianity and Islam are geographically the most widespread world religions (Bakari and Yahya, 1995; Arinze, 1997). Christianity includes different denominations such as mainline churches, Pentecostals, indigenous instituted churches among others. Christianity worldwide is over 2 billion while Islam has over 1 billion followers (Ali, 1986; Fitzgerald, 2003; Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, 2011); while, Pentecostal Christians form 8% of the world population and 27% of the total number of global Christians (Smith, 2011; The Pew forum on Religion and Public Life, 2008). Though there are no specific statistics on the exact numbers of each religious faith, it matters how each religion interact with each other. Pentecostal Christians cannot be ignored in the search for global peace if noticeable religious peace is to be realized.

African continent harbors about 48% Christians and almost 40% Muslims (Al-Masih, 1999; Koschorke et al., 2007). Again it is not possible to exactly tell the number of each faith given there are no statistics given during census. Christians in Kenya are estimated at 60 to 80 percent, while Muslim form 10 to 20 percent (Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, 2008). The country has thousands registered denominations, mostly Pentecostal Churches.

Some mainline churches in Kenya and few Christian colleges have taken the initiative of promoting an objective study of Islam (Mazrui, 2006). Knitter (1986) remarks that since 1980s, concerted efforts have been made through scholarship on understanding relationship between Christians and Muslims. Pentecostal colleges and churches are absent in such endeavors even if they form a significant numbers in Christian circles. Pentecostal Christians view Muslims as target of evangelism. Various religious differences among Christians and Muslims create need among these adherents in both faiths to learn more about each other's faith and continue to improve their relationship.

Inter-faith dialogue is evident in Christian and Muslim theology (Knitter, 1986; Miller and Mwakabana, 1998). Several passages in the Bible affirm that God is the source of all there is. This includes created being regardless of their religious order of global society (Psalms 24.1; Acts 14:17; Kibicho, 2006). The Qur’an itself contains references to Christians and indications on the way dialogue should be conducted (Qur’an 2: 136, 253, 285; 3:3, 64-65, 84, 111-115; 61:6 cf.; Kahumbi, 1995). The last three decades, mainline churches have shown some concerted efforts towards a new understanding in inter-faith dialogue.

Concerns are raised on matters of enhancing Christian-Muslim dialogue among Pentecostal Christians and Muslims. It is true that Pentecostal churches are not enthusiastic in pursuing similar efforts made by mainline churches on interfaith relations. Sometimes scholars are accused of not having an explicit guiding view among Pentecostal churches on how the Bible informs engagement in inter-faith dialogue. Indeed, based on various Biblical understanding, the urgency to share the gospel supersedes any form of interfaith dialogue.

Pentecostal churches in Nairobi appear to underline that Muslims ought to be evangelized. Christian theology is expected to promote God’s love for all humanity, portraying unconditional love, justice and tolerance regardless of one’s religious background. Ironically, even some Muslim religious leaders in Nairobi appear to exhibit a strong reservation towards efforts of inter-faith dialogue (Mutei, 2006). Subsequently, one wonders how Pentecostal churches can change their perception and responses towards Muslims and vice versa.

Christians and Muslims have been involved in inter-faith conflicts since the dawn of Islam. Inter-faith dialogue is a prerequisite to strengthen Christian and Muslim relationship. Earlier studies have focused on inter-faith dialogue from mainline churches’ perspective. This paper is timely because most of the interfaith forums between Christians and Muslims are propagated by the mainline churches, while the Pentecostal churches are absent. The study contributes to the enhancement of interfaith dialogue between Pentecostal Christians and Muslims. There is need to offer insights on varied interpretations of Biblical teachings on inter-faith dialogue by Pentecostal churches. Pentecostal and Muslim theological institutions need to incorporate courses related to inter-faith dialogue in the academic education.

Christian-Muslim dialogue historical background

We can find glimpse of religious dialogue during Prophet Muhammed and Caliphs tenure. Prophet Muhammed allowed Christians to worship in the same mosque as he did amid strong protestation from some Muslim adherents (Papademetriou, 2010:3). The prophet was criticized by his followers for allowing Christians to worship in the mosque. But his response that mosques and churches are houses of God and one can worship in any serves as a seed for interfaith relations (Ayoub and Omar, 2007; Papademetriou, 2010:3). Bowen (2010) argues that when prophet Muhammed migrated to Medina, he joined the Jewish customs of praying facing Jerusalem. Some parts of the Qur’an revealed during this time depict some similarities with Judaism, such as dietary laws. The four rightly guided caliphs (632-661) Abu Bakr al-Siddiq, Umar ibn al-Khattab, 'Uthman ibn 'Affan and Ali ibn Abi Talib, had strong religio-political undertones. This religio-political aggression has been used by later Muslims leaders to justify physical aggression against non-Muslims. Indeed, it is noted that inter-religious tolerance which is enshrined in the Qur’an has been overlooked by many radicalized Muslims. Physical aggression in the spirit of jihad has overshadowed the spirit of religious tolerance leaving little opportunity for interfaith dialogue. Religio-political interests sometimes precedence over spiritual matters; thus, adversely affecting interfaith dialogue.

Scholars argue that Christians and Muslims have a dark physical aggression and religious conflicts. This is depicted in ancient jihad; Islam radicalism and retaliatory adventures called medieval crusades for centuries (Bartlett, 2000). Nevertheless, the Conciliar Declaration marked the beginning of Christian-Muslim relations from a Roman Catholic perspective. The Second Vatican Council (1962-65) legitimized Christian-Muslim relations through the Conciliar Declaration (Michel, 2003). Pope John Paul II and the Council urged Christians and Muslims to forget the past (jihads and medieval crusades) and sincerely make effort to achieve mutual understanding to promote peace, liberty, social justice and moral values (Fitzgerald, 2003).

Christianity and Islamic faith do share some similarity. As Kenny (2003) and Helleman (2006) note, some of these similarities include monotheism, sanctity of life and religious piety. Despite these similarities, significant differences in their theology and interpretation do appear. Some mainline churches and theological institutions are promoting objective knowledge of two Abrahamic faiths. Ideally, the Catholic-Muslim Liaison Committee and World Council of Churches support Christian-Muslim dialogue based on the principle of human mutual respect.

Pentecostal and charismatic denominations are the fastest growing expression of Christianity in Kenya. Pentecostal churches are commanding a huge Sunday attendance in major towns, majority being in Nairobi. These churches are appealing to the young generation unlike most of the mainline churches. Nairobi County is home to many of such Pentecostal churches. An essential component in inter-faith dialogue, which ought to be propagated among Pentecostal churches, is that interfaith dialogue does not intend to reach doctrinal agreement; but, a willingness to re-examine one's faith in the light of others. Basically, this entails active listening, and adjusting one's own engagement and interaction with the experiences of the other. Sometimes the relationship between Christians and Muslims in Kenya lack sincerity. Some of the feature of relationship between Christians, particularly Pentecostals and Muslims rest on uninformed presumptions, stereotypes, distorted perceptions, prejudices and discrimination.

Pentecostals mission is to heed to the call of Jesus, to reach out, influence and receive people into Christian faith, including Muslims. Muslims promote a false conception of God and the gospel, thus they should be won to faith in Christ, a notion high held among Pentecostals. This included approaching Muslims with the claims of Christ through prayers, friendships, listening and proclaiming Christ to them. The basis that dialogue is not always a mode of evangelism but reaching out through Christ love, in order to progress beyond negating misconceptions of others’ beliefs and praxis.

Studies related to Christian-Muslim dialogue have come up with some varied theories that try to explain practical strategies of engaging in a harmonious inter-faith dialogue. Netland (1991), for example, is inclined to the Inclusivism Theory. Inclusivism Theory assigns ultimate status to a particular vision while acknowledging that other paths may variously participate in, reflect, or supplement the truth of this superior way. Inclusivists hold that God has revealed himself definitely in Jesus Christ and is central to God’s progressive redemptive plan. Within the Christian tradition, inclusivism takes the form of various Christocentrism (a theology underlining Christ) in matters of logical fulfillment of scriptural prophecies, where the possibility for salvation is granted to non-Christians, but only in and through the extra-ecclesial, redemptive work of Jesus Christ. Nonetheless, some theories may appear either abstract or complex in view of the exclusive nature of most theological perspectives in both Christian and Muslim religion.

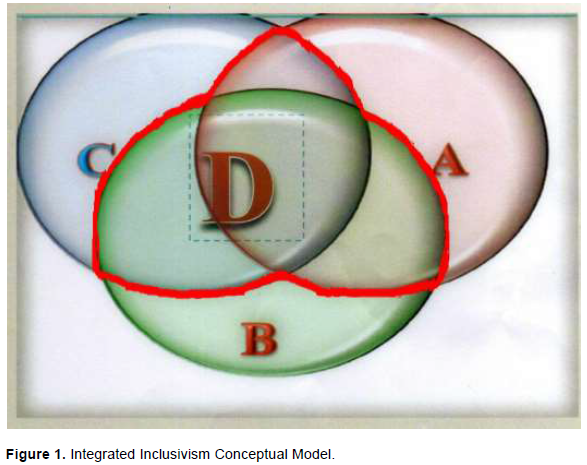

As a result of the inadequacies raised above, this paper brings about an Integrated Inclusivism Conceptual Model, which represents a paradigm of concepts and variables for Christian-Muslim harmonious relation. The Integrated Inclusivism Conceptual Model has four parts labeled A, B, C, which interact at the letter labeled D shown in Figure 1. First, labeled A is shared theological concepts and values; second, labeled B is socio-political and economic dialogue; thirdly, labeled C is divergent theological concepts; and finally, Labeled D is constructive Christian- Muslim dialogue.

Shared theological concepts and values among Christians and Muslims focus on common areas of religious belief such as orthodoxy and orthopraxy. Socio-religious values include: inter-social relationship, socio-religious grace, peace, compassion and love, trust and reconciliation, and holiness. Christians and Muslims would be comfortable in dialoguing on these areas of commonality. As indicated in several biblical and Qur’anic Qur’an 2:136; 3:3; 3:111-115; 16:125; 6:108; 29:49, peaceful co-existence is well stipulated in the Qur’an (2:62; 2:226). Other crosscutting issues supporting interfaith dialogue include Biblical prayer (Matthew 6:9-13) and Qur’anic salat (Al-Fatiha (Qur’an 1; 2:286); they appear identical in concept and wording. Pentecostal Christians if they would take time to study about creation mythology, human morality and eschatology in Both the Bible and Quran would find a glimpse of similarity and build a desire for interfaith dialogue. Some of these verses appear in Romans 1:18-27; Galatians 5:17-19; Qur’an 5:90-91; 17:32; 42:37. In both faiths, sexual sins such as adultery, fornication, homosexuality, lesbianism and same sex marriages are forbidden (Matthew 25:46; Romans 1:18-27; Qur’an 5:90-91; 13:35).

Both the Bible and Qur’an teach on socio-political and economic dialogue. This teaches on common commitment to good works, governance and leadership, justice, human liberation, development programs, trade and commerce and tolerance amidst diverse doctrines in Christianity and Islam traditions. The Bible as well as the Qur’an teach on the need to uplift the wellbeing of others. Socio-religious love and compassion is expressed to those who are downtrodden, wronged and less fortunate through the principles of courtesy, morality, uprightness, justice, fair-play, honesty and dignity (Galatians 5: 16-23; Qur’an, 2:143; 2:177; 2:188; 4:135 ; 3:103; 21:92). Islamic socio-economic systems and Islamic socio-economic trade socio-economic principle envisaged in the Qur’an (3:159; 5:8; 62:9-10) revolve around economic, trade and commercial activities which revere God. This precept of good governance embraced in the Qur’an (3:159; 42:38) is shura (consultation in decision making) within Muslims and non-Muslims in affairs that affect the community.

Divergent theological matters in both the Bible and Qur’an dictate how interfaith dialogue should be embraced theologically or practiced. Interpretation of some theological doctrinal values, scriptures and religious practices within Christians and Muslims cause disparity between them. Other aspects associated with divergent issues include the understanding of God and worship styles. Despite divergent theological issues among Christians and Muslims, there is much to learn from each other and explore together in considering the essentials and critical areas of belief and praxis between them.

Scholars writing in relations to Christian-Muslim dialogue have labored in the areas of peaceful co-existence and human relationship among these faiths as shown in parts A, B and C. Scholars have, however, given little attention on how these three areas interact to produce a constructive Christian-Muslim dialogue. It is for this reason that the study introduces new knowledge of the trilateral interaction which forms Integrated Inclusivism conceptual model. This Integrated Inclusivism Conceptual Model is formed when A, B and C interact at part D to produce constructive Christian-Muslim dialogue. Despite there being many theological values, perspective and religious practices upon which Christians and Muslims differ still there is hope for interfaith dialogue. Pentecostal Christians have hardline opinions on Biblical teaching on God’s self-revelation and inspiration of the Bible (Deuteronomy 4:2; 12:32; 2 Timothy 3:16; Revelation 22:19). For Muslims, the Qur’an holds a vital place at the very center of Muslim religious life and practice. Other doctrines such as Trinity would serve a great disparity among them (Matthew 28:19; John 1.1; John 4:23; 2 Corinthian 13:14; Qur’an 5:76; 6:133; 112:1). This creates a wide theological chasm between Islam and Christianity. The Biblical Christology implies that Jesus is the only way to eternal life (John 14:6; 1 John 2:22-23). The last item looked on the possibility of interfaith dialogue is Integrated Inclusivism Conceptual Model. Genuine and effective dialogue must address integrally the issues raised above in A, B and C. The paradigm includes interaction of cross-cutting issues in Biblical and Qur’anic teachings on inter-faith dialogue, such as belief in God, prayers, morality and eschatology.

Jesus’ ministry was inclusive in nature. In his earthly ministry, Jesus, encountered non-Jews and responded to their felt needs; for instance, the Roman Army commander (Matthew 8:5; John 4:45-54) and the Canaanite women (15:21-28) among other persons. Multicultural and multi-religious contemporary societies can only excel through Inclusivism Conceptual Model of religion.

The Bible and Qur’an address matter relating to interfaith dialogue in various ways. We have evidence from the Biblical and Qur’anic teachings on the possibility of interfaith dialogue. Such scriptural teachings point to socio-religious, socio-economic, as well as, leadership and governance values pertinent to Christian-Muslim dialogue. The Qur’an regards previous divine revelation, including the Bible, as authentic documents for spirituality. Such acknowledgement forms a basis to respect religious plurality as a means of developing a social community. In addition, Biblical and Qur’anic teachings on inter-faith dialogue recognize matters of doctrinal divergence. Pentecostal Christians and Muslims need to approach interfaith dialogue and theological interaction more openly in order to overcome undue religious misunderstandings.

There is strong evidence that Christianity formed the spiritual and moral values mostly found in Islamic teachings. From its inception, Islam grew in a milieu which permitted interfaith dialogue. This is evidenced by Prophet Muhammed’s positive attitude towards interfaith initiative between Christians and Muslims. He gave privileges and protection to Christians under his jurisdiction. He admired Christian piety, love, humility and faith. Upon his death, his successors, the four Rightly Guided Caliphs favored interfaith dialogue, even as they exercised religio-political leadership. Pentecostal Christians and Muslims in Nairobi should benefit from interfaith relations that transcend accusations and counter-accusations to a unity of basic principles found in religious teachings. This will lead to a more meaningful and open discussion in a spirit of love and respect. Pentecostal congregations and Muslim umma in Nairobi are numerically increasing. This is mostly attributed to evangelism and da’wa. Numerical religious growth sometimes comes with challenges, especially religious conflicts. It is, therefore, important for religious leaders, organizations and political leaders to spearhead the spread and acceptance of interfaith dialogue in Nairobi. Pentecostal Christians and Muslims should prioritize the agenda of enhancing interfaith dialogue. Acceptance of each other reduces to a greater level, religious exclusivism. It is insufficient to read other religious systems in light of one’s own theological or reader presupposition. There is a need to move interfaith dialogue from the corridors of academia to contextual realities of the masses with plain medium of communication.

Christian-Muslim dialogue in Nairobi can best be enhanced by appropriate strategies. There is need to underscore that religious leaders, political leaders and organizations are critical organs in developing effective Christian-Muslim dialogue. Christian-Muslim dialogue can be promoted by first, resolving outstanding perceived religious conflicts. This would assist Christians and Muslims to develop conflict resolution mechanisms and minimize intolerance. Through interfaith forums, shared and divergent theological issues and theological aspect should be objectively discussed to realize constructive dialogue. There is need to embrace interfaith dialogue not as a compromise of major doctrines, but as a means to being inclusive. It is through interfaith dialogue that solutions can be found for effective dialogue between Pentecostal Christians and Muslims in Nairobi. Youthful Christians and Muslims should be theologically trained to propagate interfaith dialogue. Religious leaders should address social evils in the community. Such evils adversely impact on interfaith dialogue. Pentecostal and Muslim religious leaders have incredible influence over their members. Equal partnership in status of interfaith dialogue should be embraced by Muslims and Pentecostal Christians. Religious equality in interfaith relations is vital in enhancing Christian-Muslim dialogue. Pentecostal Christians and Muslims working as equal partners in dialogue lead participants to be open, honest and committed to developing personal relationships.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.