ABSTRACT

This study is set out to investigate poverty and women in the informal sector with evidences from urban areas of Eritrea. The study uses descriptive technique on primary data collected using interview and questionnaire from 12 towns distributed throughout the 6 administrative regions of the country. The approach adopted includes both a survey and structured interviews targeted at women who are active in the informal business sector. The main findings from the sample data of 1604 women collected indicate that majority of the respondents are poor as their monthly income hovers around the poverty line set by the world bank (of one dollar and fifteen cents per day). Furthermore, it has been noted that the greater part of women interviewed are active as petty traders, followed by services and only a minority of them are active in the manufacturing (production) sector. Poverty and unemployment are the two main driving forces that made them to try their chance by making themselves active in this sector. However, they lack the entire necessary infrastructure and amenities to facilitate their businesses as the majority of them work in open public places under continuous harassment and uncertainty. They do need legal and social protection, place of work, training, credit and other amenities if they are going to expand their business and go out poverty. The result shows the situation and plight of women in informal sector in the country and the paper therefore recommends that policy makers take notice of their situation and give more support and formulate policies that will provide an enabling environment for the growth, expansion and prosperity of the sector in general and women working in the sector in particular.

Key words: Women, informal business, developing country, Eritrea.

Once seen as a “temporary phenomenon” that would be eliminated by economic development, the informal sector now threatens to become the standard experience of workers in developing countries (Agarwala, 2009). Scholars give different theories of what contains and gives rise to informality. Many economists assert that people who engage in the informal economy choose - or volunteer—to work in the sector out of their own will (Maloney, 2004). However, others claim that in addition to choice economic crises or downturns in nations’ economies also drives people to join the ranks of informal employment. Other observers point out that contemporary economic growth, globalization and labor reforms in the developed world are also inducing formal firms to subcontract their works to the informal sector and informal wage workers or households and this event is growing fast in many countries. In reality there is increasing recognition by many that different factors play a role for the existence of different segments of the informal economy simultaneously. In recent years, several sets of observers have posited models that seek to capture the components of informality and/or the different factors driving informality.

The informal economy is thus no longer considered a temporary phenomenon. Furthermore, the informal economy has been observed to have more of a permanent character in developing as well as in many advanced countries. But it is particularly important in developing countries, where it comprises one half to three-quarters of nonagricultural employment: specifically, 48 per cent in northern Africa; 51 per cent in Latin America; 65 per cent in Asia; and 72 per cent in sub-Saharan Africa.

Throughout the developing world, informal sector is generally a larger source of employment than the formal employment and it is even more so for women than for men.

With the exception of Northern Africa, where only 43 per cent of women workers are engaged in informal employment, 60 per cent or more of women workers in the developing world are in informal employment (outside agriculture) (Chen et al. 2005). Sub-Saharan Africa witnesses the largest number (84 per cent) of women non-agricultural workers being employed in the informal sector as compared to 63 per cent of men. In case of Latin America the figures are 58 per cent of women in comparison to 48 per cent of men. In Asia, the proportion is 65 per cent for both women and men (Chen et al., 2005).

Scholars argue that the informal sector is seen as a positive influence on the economies because it can create more jobs and grow more quickly than the formal sector. In general, the informal sector contributes to the nation’s income; it creates employment and has an important linkage with the formal sector of an economy (Blunch and Dhushyanth, 2001; Chen, 2001; Charmes, 2000; Hussmanns, 2004). Similarly, others argue that the informal economy provides a solution to poverty and economic problems of developing countries and it is a useful tool in improving the economic situation of the poor as it generates employment and income to the poverty-ridden masses (Rakowski, 1994; Moser, 1994).

Despite the sectors’ contribution one still observes that there is still rampant poverty raging among those who are active in this sector. As a result many observers associate poverty with the informal sector. Some scholars express their concern over the tendency to conflate informality and poverty as one and the same. The fact that most of the world’s poorest people work in the informal economy leads some observers to use the terms “informal” and “poor” almost synonymously, as well as other terms associated with vulnerability such as “marginalized,” “excluded,” or “precarious.” But not all informal workers are poor and not all working poor are engaged in the informal economy (Peattie, 1987). Some informal operators – especially among those who hire others – are not poor and some formal wage workers are poor. But there is a significant overlap between working in the informal economy and being poor.

Scholars claim that a narrow focus on imbalances between formal and informal workers may lead us to overlook hierarchies within the informal economy. Thus the links between employment, gender, and poverty can be seen by comparing (a) average earnings in formal and informal employment and (b) average earnings of different categories of informal employment.

Based on a review of five research studies spanning 20 developing and newly industrialized countries, scholars found—not surprisingly—that formal workers earn higher average incomes than do informal workers (Charmes, 1998, WIEGO, 2012).

As noted above, the informal sector is diverse and segmented. The different segments are associated with different earning potentials that would be concealed by the average for the informal economy as a whole. Accordingly WIEGO’s (Women in Informal Employment, Globalizing and Organizing- an international advocacy group) more remarkable finding is that an income and poverty risk hierarchy exists within the informal economy that looks alike across countries. Informal employers have the highest average earnings and lowest risk of poverty. Regular informal employees who work under informal employers have the second higher average earnings. Informal industrial outworkers earn the lowest wages, followed by casual wage workers and domestic workers, then followed by own account workers (Chen et al., 2005). In this hierarchy men are overrepresented at the top of this economic pole, and women at the bottom. Within the informal economy, women are disproportionately represented in work associated with low and unstable earnings and with high risks of poverty.

According to WIEGO’s holistic framework more women are employed in the informal economy than the formal economy. As abovementioned the informal sector accounts for the lion’s share of employment for women but less so for men. The fact that women tend to be under-represented among informal employers and “regular” informal wage workers and overrepresented among industrial outworkers, own account workers, domestic workers and unpaid contributing workers in family enterprises leads to a gender gap in average earnings and in poverty risk within the informal economy. To wrap up evidences in many countries all ascertain that an overlap exists between being a woman depending on informal employment and being poor at the same time (Chen et al., 2005).

In this study we adopted WIEGO’s multi-segmented model of informal employment defined in terms of statuses in employment (Table 1). The model features six categories of employment namely — informal employers, informal employees, own account operators, casual wage workers, industrial outworkers or subcontracted workers, and unpaid but contributing family workers — and these are defined by the type/degree of average earnings and risk of poverty. In addition, the model shows the links between informality, poverty, and gender. WIEGO’s framework displays that women in the informal sector are more likely to be concentrated in low-paid jobs and women’s jobs are more likely to be huddled in low value-added sectors; and in low-paid jobs characterized by poor working conditions without social security and legal protection.

The benefits of informal employment to women working in the sector are often not sufficient and the costs are often too high to achieve an adequate standard of living over their working lives. In general, only informal employers who hire others earn enough to predictably rise above the poverty threshold and there are many empirical evidences that prove the above statements (Chen et al., 2005) (Figure 1).

In addition the informal economy is excluded from the benefits and rights incorporated in the laws and administrative rules covering property relationships, commercial licensing, labor contract, financial credit and social security systems (Seligson, 1996).

As in other developing countries, the number of informal businesses in Eritrea, in particular those owned by women entrepreneurs, is increasing. The Government of Eritrea launched its National Macro-Policy in 1994 and in this document advocates for upgrading and improving the human and material capacity of the informal sector for efficiency and quality production of goods and services.

Anecdotal evidences indicate that the Eritrean informal sector attracts many women and contributes to their income generation and employment creation; however, there is lack of relevant data to substantiate this argument. Hence it is imperative to know the demographic and socioeconomic situation of women engaged in the sector. It is with this intention in mind that this research is launched.

Since this report is the first of its kind for Eritrea, it provides new knowledge regarding the informal business in Eritrea in general and the participation of women in this sector in particular. This research highlights the types of informal business activities run by women, employment characteristics, and ownership structures. Moreover, it highlights policy interventions needed to empower women and achieve gender equality and equity.

The main objective of this study is to evaluate the degree of poverty of women working in the informal sector in the urban areas of Eritrea. Moreover, the study endeavors to see the magnitude and ability of the informal sector in income generation and employment creation for women active in the sector. The overall approach is to undertake research through questionnaire survey and structured interviews amongst representative sample of women in the informal business sector in the six administrative regions of Eritrea Central Region (CR), Western Region (WR), South Region (SR), Anseba Region (AR), Southern Red Sea Region (SRDR), and Northern Red Sea Region (NRDR). Similar studies using surveys have also been conducted in other African countries. However, this study is unique for several reasons. First, the sample of this study is only women where their problems may not be overshadowed by male population. Second, this study comprises a large sample survey and district areas compared to some surveys undertaken in other studies in Africa.

A representative sample of cities from the six regional administrations of Eritrea was selected for the purpose of this survey. Based on expert opinion, employment and logistical reasons, the approach used in selecting the cities for the survey and the allocation of questionnaires was the number of population. That is, all large cities with more than 20,000 inhabitants in Eritrea are included in this study (Table 2).

In order to identify all settlements and size within which selected informal businesses to be surveyed and relevant issues to be studied, a detailed discussion was held with concerned Ministries and other relevant government agencies. Furthermore, some previous studies on Small and Medium sized Enterprises (Yacob, 1996) and Demographic and Health Survey (Government of Eritrea, 2002) were referred.

This study employs mainly quantitative data. Data on women in the informal business was collected through a highly structured self-administered questionnaire designed to elicit quantitative data and these was collected from the selected cities of all regional administration of Eritrea. A total of twelve (12) cities have been selected for the survey. Care was taken to ensure that a representative sample of women was obtained from each region. Initially it was estimated that a sample of about 1,500 women in the informal business would be conducted for the study. We took the percent distribution of women employed in the six regions working in five areas such as professional/technical/managerial, clerical, sales and services, skilled manual, and unskilled manual as a base for selecting (sampling) the proportion of women operating in the informal sector. However, we excluded women who work in agriculture and domestic service because according to International Labour Organisation (ILO) informal business is confined to non-agricultural units and non-domestic services.

Based on the Demographic Health Survey (Government of Eritrea, 2002) it was found that the highest proportion of women employed is in Central Region. If we exclude those who work in domestic service and agriculture, the majority of women employed in the informal sector are found in Central Region. Hence, it was a good proxy for this study to take a sample of 50 percent of women in the informal business sector from Central Region. Table 1 shows the calculations used to derive the percentage distribution and the questionnaires required in each region.

Thus, since the selection of the sample size and the decision on the areas to be visited was guided by the Demographic and Health Survey, the sample for this study is 1,504 enterprises. Nevertheless, for the purpose of replacing missing questionnaires, we decided to collect more data and we distributed 1,625 questionnaires, but 18 were incomplete because more than half of the items asked were not answered. This produced a sample of 1,607 usable questionnaires (103 questionnaires over the original sample).

An attempt was made to include all categories of informal business that women operate. Most of the subjects are visible since they operate from public places; however, there are a small number of women whose activities are not visible (those who are engaged in preparing bread, preparing bridal and birthday items such as sweets and banners).

Employment and physical characteristics of the informal businesses in Eritrea

As the aim of this study is to identify the types of informal business activities run by women, employment characteristics, and ownership structures…etc., a wide range of informal sector activities was covered in this study. Table 2 shows the type of activities which were covered in this study.

To the best of our knowledge, since no data exists on the population of women in the informal business sector, one cannot make a definitive statement on the proportion of women in the informal sector activities which the sample represents. The single largest number amongst the activities covered was trade (67.1 percent). Furthermore, it has been revealed that the predominant activities of the informal sector are providing service and handcraft. Manufacturing is the least of all. This is understandable since production of resource-intensive commodities amongst women in Eritrea is extremely low.

Socio-economic profile of business owners

The data set in this subsection describes the socio-economic profile of the survey. The data includes the reasons for starting informal business, the ownership structure of the informal enterprises and the period of time that the informal businesses have been in operation. In addition it includes also the number of informal businesses owned by the respondents and the employment characteristics of their businesses.

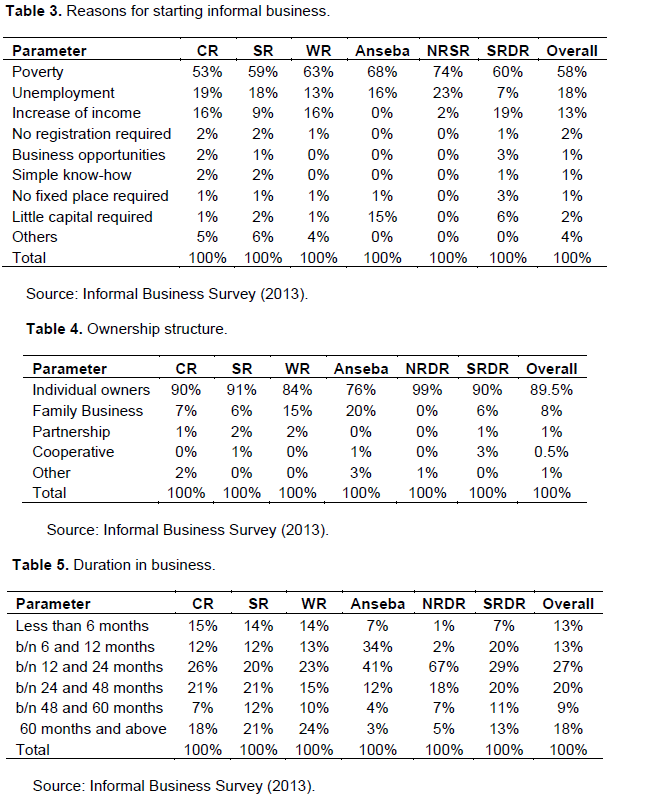

The information presented in Table 3 indicates that the main reason for starting informal business in the survey areas is poverty, accounting for 58% of the respondents. The only other two notable reasons provided are unemployment and increasing (raising) income with 18% and 13% respectively. What are evident from these figures are that very few of the respondents indicated entrepreneurial reasons (such as exploitation of business opportunity) as a reason for starting an informal business. This suggests that the majority of informal business owners are forced into this sector of business as a result of rampant poverty and high level of unemployment. The number of women who enter into informal business sector to exploit existing business opportunities is extremely negligible.

The comparative information in Table 3 indicates that poverty is the main reason for starting an informal business in all six regions, ranging between 53% in Central Region and 74% in Northern Red Sea. Unemployment as a reason for starting informal business is indicated by 19% of respondents in Central Region, and given as a reason by between 7 and 18% in the other zobas. The percentages in the table clearly indicate that the importance of widespread poverty and persistent unemployment are forcing people to engage in the informal business sector.

Ownership structure

Regarding ownership, the majority (89%) of all enterprises are owned by one person. Another 8% of the enterprises are family businesses. Businesses having the ownership character of partnerships and cooperative are negligible. Evidences indicate that this pattern of ownership structure is widespread in the formal business sector of Eritrea (Yacob, 1996). Table 4 shows the ownership structure of the informal business.

The comparative data in Table 4 indicates that individual ownership is the dominant ownership structure in all six regions, ranging from 76% in Anseba to 99% in Northern Red Sea. The second highest occurrence of ownership structure is family owned informal businesses which is found in Western Region and Anseba with 15 and 20% respectively. The percentages in the table clearly indicate that individual ownership is the dominant type of ownership structure in the informal business sector.

Duration of operation of the informal businesses

The information depicted in Table 5 is indicative of the existence of relatively young informal businesses in the country. The majority of respondents (87%) indicated that their businesses have been in operation for less than four years. It is only a small proportion of the respondents, that is, 18% who reported that their business have been in operation for more than four years.

A comparative analysis of informal businesses at nation wide indicates that the highest proportions of relatively old informal businesses (four years and above) are to be found in the Central, South and Western Regions. In these areas, 18% of Central Region, 21% of South and 24% Western regions respondents indicated that they have been in operation for more than four years. On the other hand the highest proportion of informal businesses that have been in existence between one and two years are located in Anseba and Northern Red Sea with 41% and 67% of respondents respectively. On average, majority of the respondents asserted that they have been in business between the time periods of one to three years. In general one can observe that majority of the businesses are young endeavors.

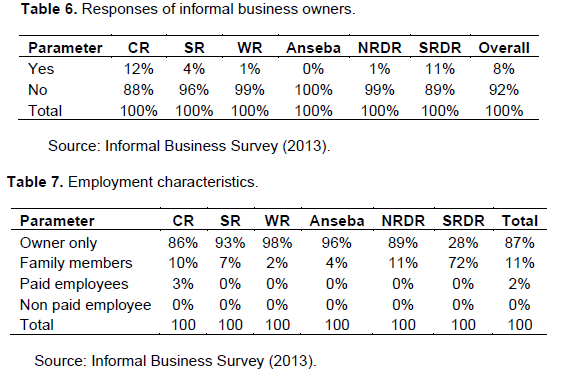

Number of informal businesses owned by the respondents

The survey data indicates that the majority of respondents (92%) own only one informal business. A total of 8% of the respondents indicated that they own more than one business. From the 8% respondents, 69% own one more business, 26% own two more businesses and a small group (5%) owns three more businesses. Table 6 provides the results. The comparative data at regional level indicates that the highest occurrences of informal business owners with more than two or more business are found in Central and South Regions. Informal business owners in Anseba have all reported to have only one business. Out of those respondents who affirmed to have more than one business, who reside in Western Region, Northern and Southern Red Sea, have only one more additional business.

Employment Characteristics

As far as employment characteristics, the majority (87%) of the informal businesses are owner operated one person businesses. A few businesses (11.2%) engage family members as helping hand and only (1.7%) of the respondents hire paid hand in running their businesses. As can be seen from Table 7, the respondents of almost all regions, except those residing in Southern Red Sea, reported that they have owner operated one person businesses. The majority of respondents from Southern Red Sea reported that they involve family members as helping hand in running their business. This indicates that the majority of these businesses are small in character and a woman’s ventures.

Physical characteristics of informal businesses

The data set in this subsection describe the physical characteristics of informal businesses. The physical structures, places and location sites from which respondent perform their business is discussed firstly followed by the availability or lack of facilities on the business sites such as electricity, water, telephone line, toilet. Finally, we discuss the mode of transport used by respondents in running their ventures.

Regarding the business site, as Table 8 reveals the majority of informal business respondents (38%) conduct their activities on streets or open spaces. The second notable categories are market place and home backyards with 15 and 11% respectively. A few respondents (15%) conduct their business by moving from place to place (mobile). This shows that the majority of the respondents are poor women owners of petty retail activities. They run their informal businesses from a street or other urban open spaces in order to earn their living.

The proportions of informal businesses operating from the street are very similar across all six regions, ranging from 34% in Northern Red Sea to 51% of respondents in Anseba. A notable exception to the above trend is the case of Southern Red Sea where only 13% of the informal business respondents of the region work from the street. This could be related to the weather conditions of the region that may hinder people from working on the streets in day time. Alternatively the majority of respondents from Southern Red Sea and South operate in market places and from home backyards, respectively.

Availability of services

A total of 85 % of the respondents in the survey area indicated that their businesses have no access to any kind of facilities (electricity, water, toilet, telephone) and this is related to the fact that the majority of our respondents run their business from open spaces, streets and public markets, where in many cases; the aforementioned facilities are not available. Out of those who responded positively to have some access 30 % claimed to have access to electricity and 55% to water. Furthermore 13.5% of respondents declared that they own mobile phones.

Regional analysis shows that the informal businesses in Western Region are operating without electricity. Similarly informal businesses in Northern Red Sea are operating without water facility. Many of the informal businesses have no access to toilet and telephone facilities. Generally speaking the majority of the informal businesses are deprived of all the facilities mentioned above. Table 9 presents the results.

Mode of transportation used

Majority of our respondents (56%) asserted that they carry physically on their shoulders whenever they want transport merchandise from suppliers. Other notable means of transport used by informal businesses is public buses (24%). The remaining modes of transportation play a very limited role in serving the

informal businesses.

In all the regions, the informal business owners use their own shoulders as the main means of transporting their merchandise from place to place. In addition, informal business owners in all the regions use public buses as a second alternative method of transport. Moreover (20%) of the respondents from Western Region and (14%) of respondents from Central Region use animal cart and manual carts respectively as a means of transporting their goods. The results are provided in Table 10.

DISCUSSIONS AND RECOMMENDATION

Contrary to the expectation of much of the early development literature, the informal sector has not only persisted but also flourished in many developing countries, particularly in Africa. Thus, the informal economic activity has grown to be a subject by many scholars and policy makers alike. They have started to see the sector as a dynamic phenomenon, which have a significant impact in the economy as income and employment generating mechanism.

Correspondingly evidences indicate that the Eritrean economy includes a sizeable number of informal sector activities. It is opportune time to explore the sector in general and the situation of women engaged in the sector in particular.

The literature reviewed indicated that informal economy provides opportunities for income earnings for those that have no other means to survive. In the empirical study that we have conducted in Eritrea, poverty, unemployment, lack of education and family problems are motivating women to engage in informal businesses. In Eritrea, people, in particular women are hardworking and hate dependency. For many women the informal business work is found to be the only means of support to themselves and their families at time of difficulty.

The main objective of this work is to investigate whether the informal sector is contributing towards women’s’ poverty alleviation or not. We take the World Bank’s Poverty Line indicator of $1.25 a day. The official Eritrean currency the Nakfa has been pegged to the US dollar at one US dollar to fifteen Nakfa ($1US =15 Nakfas) and this pegging has been going on for more than a decade. Even though it is illegal there exists also, as in many other developing countries, a parallel black market thriving around at an exchange rate of one US dollar to thirty Eritrean Nakfa ($1US = 30 Nakfas) on average. As it is indicated on the earnings table above the majority of women taking part in informal sector just earn five hundred (500) Nakfas or less than that a month. This simply portends that the majority of these women are just surviving on nineteen Nakfas (19 Nakfas) per day

[1]. Even taking the official exchange rate than the parallel unofficial exchange rate still one can observe that the majority of these women are still hovering around the poverty line and are using the work they have in this sector as a survival strategy protecting themselves and their families from utter starvation and deprivation than an occupation with a future. Even though as aforementioned the participants wish with the help of this sector to move out of poverty they are still under or marginally above the poverty line.

Moreover, majority of the women are active in low value petty trading and service activities rather than in high value adding manufacturing activities. This corresponds with what we observe in other countries in which majority of women participate in low value adding activities and earn much below than their male compatriots.

As these women lack appropriate permanent space and suitable location to work and the majority of them work as market or street vendors, hawkers or homeworkers, they are expose to physical safety and health risks. For instance they are exposed to burning heat from the sun during daytime and to severe cold during the evenings. Moreover, many of them are keeping their underage children with them. Furthermore, the informal businesses have no access to any kind of facilities (electricity, water, toilet, telephone) further hampering their businesses. In addition, the lack of permanent place with storage exposes them to additional payment of rent and theft

[2].

Many women in the informal business are operating from foot paths and streets. They do not have license to

operate and; thus they live with the fear of confiscation, eviction and harassment by the cities’ Municipality Police. An interviewee that we found selling clothes near the old bus station of Asmara expressed the problem of confiscation and eviction they are facing as follows: “I was working in the construction industry, however, when construction stopped, I started informal business. I have been here for a month and I did not sell a single article. We spend the day playing hide and seek with the municipality police.”

Thus, the benefits of informal employment are often not sufficient and the costs are often too high for those who work informally to achieve an adequate standard of living over their working lives. Hence, a permanent place and suitable location can help women engaged in the informal businesses get security, shade and customers.

Addressing the living and working conditions of female informal workers improves their productivity, which leads to increased income and alleviation of poverty. Thus it is prime time that gender inequity in the informal economy be taken into account in development planning of the country. The following points are some of the recommendations that are necessary for the improvement of working and living conditions of women in the informal sector in Eritrea.

1. Provision of social protection including communal health insurance, improving occupational safety and reducing work hazards, improving access to child care, and building informal workers’ alliances and networks are some of the ways that can be undertaken to improve the conditions of women working in the informal.

2. Increase and diversify access to formal finance for women, including microfinance. Microfinance has clearly proven to be an effective tool in facilitating women's access to credit and micro finance institutions have potential of channeling financial resources to the poor, with positive impact. However, microfinance institutions have not yet proved to be successful with the poorest of the poor thus they have to design strategies to reach the most deprived part of the society.

3. Some of the existing legal and regulatory frameworks do not fully protect the fundamental rights of women working in the informal sector. This draw attention to the need to amend and reform the legal and regulatory regimes to correspond with the needs of this sector.

4. The market has no moral obligation of extending protection to vulnerable women working in the informal sector but is always ready to exploit and abuse the basic right of these people. This underscores the role of state in mitigating negative impact of free market through proactive rules and regulations. Isolated social security schemes should complement government efforts in extending social protection to informal sector women.

[1] If we divide 500 Nakfas by 30 days majority of these women earn on average 16.70 Nakfas per day and multiplying this by $1.25 US dollars we get 18.75 Nakfas (more or less 19 Nakfas). On the other hand if we take the unofficial one (30 Nakfas per day) and multiply it by $1.25 US dollars the amount is 37.5 Nakfas. Unofficially a person needs 37.5 Nkfas per day to survive. This is far away from the official one (18.70 Nkfas).

[2] Working in open places is exposing the women to theft. An interviewee with a woman who lost over Nakfa 15, 0000 due to theft stated the following: “

In 2006, when I was nine months pregnant I was selling clothes. During one evening, I packed my property in a sack and I was preparing to go home. However, when I turned around to pick my stool, a thief came unnoticed and grabbed the sack. He put the sack in his bicycle and run off. I could not catch him because I had a problem and people shouted thief, but to no avail. I lost a lot. Had our place had a store here and a shade I would have avoided this loss.”

REFERENCES

|

Agarwala R (2009). An Economic Sociology of Informal Work: The Case of India," in Nina Bandelj (ed.) Economic Sociology of Work (Research in the Sociology of Work, Volume 18), Emerald Publishing Limited. pp. 315-342.

|

|

|

|

Blunch NCS, Dhushyanth R (2001). The Informal Sector Revisited. A Synthesis Across Space and Time, The World Bank.

|

|

|

|

Charmes J (1998). Women Working in the Informal Sector in Africa: New Methods and New Data. Director of Research French Scientific Research Institute for Development and Co-operation.

|

|

|

|

Charmes J (2000). Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) Second Annual Meeting, Cambridge, Massachusetts. pp. 22-24.

|

|

|

|

Chen MA (2001). Women in the Informal Sector: a Global Picture, the Global Movement," Radcliff Institute for Advanced Study.

|

|

|

|

Chen M, Joann V, Francie L, James H, Renana J, Christine B (2005). Progress of the World's Women 2005: Women, Work and Poverty, UNIFEM, New York.

|

|

|

|

Government of Eritrea (2002). Eritrea Demographic and Health Survey, Asmara, Eritrea.

|

|

|

|

Hussmanns R (2004). Measuring the Informal Economy: From employment in the Informal Sector to Informal Employment", International Labor Office, Geneva.

|

|

|

|

Maloney WF (2004). Informality Revisited. World Dev. 32:7.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Moser CON (1994). The Informal Sector Debate, Part 1: 1970-1983, in C. A. Rakowski (ed.), Contrapunto: The Informal Sector Debate in Latin America, Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 11-29.

|

|

|

|

Peattie L (1987). An Idea in Good Currency and How it Grew: the Informal Sector. World Dev. 15(7):851-860.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Rakowski CA (1994). The Informal Sector Debate, Part 2: 1984-1993", in C.A. Rakowski (ed.) Contrapunto: The Informal Sector Debate in Latin America, Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 31-50.

|

|

|

|

Seligson AL (1996). Women in the Costa Rican Informal Sector: Causes for Success, Senior Honors Thesis, Columbia University.

|

|

|

|

WIEGO (2012). Informal Economy: History and Debates.

View

|

|

|

|

Yacob F (1996). A Study of the Private Sector in Eritrea: With Focus on the Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises, Prepared for the Macro Policy and International Economic Cooperation, The State of the Government of Eritrea, Asmara, Eritrea.

|